The first and most iconic of all the Choose Your Own Adventure books involved spelunking, just as did the first and most iconic of all computer-based adventure games.

These books were the gateway drugs of interactive entertainment.

— Choose Your Own Adventure historian Christian Swineheart

My first experience with interactive media wasn’t mediated by any sort of digital technology. Instead it came courtesy of a “technology” that was already more than half a millennium old at the time: the printed book.

In the fall of 1980, I was eight years old, and doing my childish best to adjust to life in a suburb of Dallas, Texas, where my family had moved the previous summer from the vicinity of Youngstown, Ohio. I was a skinny, frail kid who wasn’t very good at throwing balls or throwing punches, which did nothing to ease the transition. Even when I wasn’t being actively picked on, I was bewildered at my new classmates’ turns of phrase (“I reckon,” “y’all,” “I’m fixin’ to”) that I had previously heard only in the John Wayne movies I watched on my dad’s knee. In their eyes, my birthplace north of the Mason Dixon Line meant that I could be dismissed as just another clueless, borderline useless “Yankee,” a heathen in the eyes of those who adhered to my new state’s twin religions of Baptist Christianity and Friday-night football.

I found my refuge in my imagination. I was interested in just about everything — a trait I’ve never lost, both to my benefit and my detriment in life — and I could sit for long periods of time in my room, spinning out fantasies in my head about school lessons, about books I’d read, about television shows I’d seen, even about songs I’d heard on the radio. I actually framed this as a distinct activity in my mind: “I’m going to go imagine now.” If nothing else, it was good training for becoming a writer. As they say, the child is the father of the man.

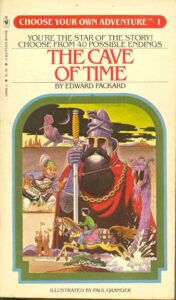

One Friday afternoon, I discovered a slim, well-thumbed volume in my elementary school’s scanty library. Above the title The Cave of Time was the now-iconic Choose Your Own Adventure masthead, proclaiming it to be the first book in a series. Curious as always, I opened it to the first page. I was precocious enough to know what was meant by a first-person and third-person narrator of written fiction, but this was something else: this book was written in the second person.

You’ve hiked through Snake Canyon once before while visiting your Uncle Howard at Red Creek Ranch, but you never noticed any cave entrance. It looks as though a recent rock slide has uncovered it.

Though the late afternoon sun is striking the surface of the cave, the interior remains in total darkness. You step inside a few feet, trying to get an idea of how big it is. As your eyes become used to the dark, you see what looks like a tunnel ahead, dimly lit by some kind of phosphorescent material on its walls. The tunnel walls are smooth, as if they were shaped by running water. After twenty feet or so, the tunnel curves. You wonder where it leads. You venture in a bit further, but you feel nervous being alone in such a strange place. You turn and hurry out.

A thunderstorm may be coming, judging by how dark it looks outside. Suddenly you realize the sun has long since set, and the landscape is lit only by the pale light of the full moon. You must have fallen asleep and woken up hours later. But then you remember something even more strange. Just last evening, the moon was only a slim crescent in the sky.

You wonder how long you’ve been in the cave. You are not hungry. You don’t feel you have been sleeping. You wonder whether to try to walk back home by moonlight or whether to wait for dawn, rather than risk your footing on the steep and rocky trail.

All of this was intriguing enough already for a kid like me, but now came the kicker. The book asked me — asked me!! — whether I wanted to “start back home” (“turn to page 4”) or to “wait” (“turn to page 5”). This was the book I had never known I needed, a vehicle for the imagination like no other.

I took The Cave of Time home and devoured it that weekend. Through the simple expedient of flipping through its pages, I time-traveled to the age of dinosaurs, to the Battle of Gettysburg, to London during the Blitz, to the building of the Great Wall of China, to the Titanic and the Ice Age and the Middle Ages. Much of this history was entirely new to me, igniting whole new avenues of interest. Today, it’s all too easy to see all of the limitations and infelicities of The Cave of Time and its successors: a book of 115 pages that had, as it proudly trumpeted on the cover, 40 possible endings meant that the sum total of any given adventure wasn’t likely to span more than about three choices if you were lucky. But to a lonely, hyper-imaginative eight-year-old, none of that mattered. I was well and truly smitten, not so much by what the book was as by what I wished it to be, by what I was able to turn it into in my mind by the sheer intensity of that wish.

I remained a devoted Choose Your Own Adventure reader for the next couple of years. Back in those days, each book could be had for just $1.25, well within reach of a young boy’s allowance even at a time when a dollar was worth a lot more than it is today. Each volume had some archetypal-feeling adventurous theme that made it catnip for a kid who was also discovering Jules Verne and beginning to flirt with golden-age science fiction (the golden age being, of course, age twelve): deep-sea diving, a journey by hot-air balloon, the Wild West, a cross-country auto race, the Egyptian pyramids, a hunt for the Abominable Snowman. What they evoked in me was as important as what was actually printed on the page; each was a springboard for another weekend of fantasizing about exotic undertakings where nobody mocked you because you had two left feet in gym class and spoke with a stubbornly persistent Northern accent. And each was a springboard for learning as well; this process usually started with pestering my parents, and then, if I didn’t get everything I needed from that source, ended with me turning to the family set of Encyclopedia Britannica in the study. (I remember how when reading Journey Under the Sea I was confused by frequent references to “the bends.” I asked my mom what that meant, and, bless her heart, she said she thought the bends were diarrhea. Needless to say, this put a whole new spin on my underwater exploits until I finally did a bit of my own research about diving.)

Inevitably, I did begin to see the limitations of the format in time — right about the time that some of my nerdier classmates, whom I had by now managed to connect with, started to show me a tabletop game called Dungeons & Dragons. Choose Your Own Adventure had primed me to understand and respond to it right away; it would be no exaggeration to say that I saw this game that would remake so much of the entertainment landscape in its image as simply a better, less constrained take on the same core concept. Ditto the computer games that I began to notice in a corner of the bookstore I haunted circa 1984. When Infocom promised me that playing one of their games meant “waking up inside a story,” I knew exactly what they must mean: Choose Your Own Adventure done right. For the Christmas of 1984, I convinced my parents to buy me a disk drive for the Commodore 64 they had bought me the year before. And so the die was cast. If Choose Your Own Adventure hadn’t come along, I don’t think that I would be the Digital Antiquarian today.

But since I am the Digital Antiquarian, I have my usual array of questions to ask. Where did Choose Your Own Adventure, that gateway drug for the first generation to be raised on interactive media, come from? Who was responsible for it? The most obvious answer is the authors Edward Packard and R.A. Montgomery, one or the other of whose name could be seen on most of the early books in the series. But two authors alone do not a cultural phenomenon make.

“Will you read me a story?”

“Read you a story? What fun would that be? I’ve got a better idea: let’s tell a story together.”

— Adam Cadre, Photopia

During the twentieth century, when print still ruled the roost, the hidden hands behind the American cultural zeitgeist were the agents, editors, and marketers in and around the big Manhattan publishing houses, who decided which books were worth publishing and promoting, who decided what they would look like and even to a large extent how they would read. No one outside of the insular world of print publishing knew these people’s names, but the power they had to shape hearts and minds was enormous — arguably more so than that of any of the writers they served. After all, even the most prolific author of fiction or non-fiction usually couldn’t turn out more than one book per year, whereas an agent or editor could quietly, anonymously leave her fingerprints on dozens. Amy Berkower, a name I’m pretty sure you’ve never heard of, is a fine case in point.

Berkower joined Writers House, one of the most prestigious of the New York literary agencies, during the mid-1970s as a “secretarial girl.” Having shown herself to be an enthusiastic go-getter by working long hours and sitting in on countless meetings, she was promoted to the role of agent in 1977, but assigned to “juvenile publishing,” largely because nobody else in the organization wanted to work with such non-prestigious books. Yet the assignment suited Berkower just fine. “As a kid, I read and loved Nancy Drew before I went on to Camus,” she says. “I was in the right place at the right time. I didn’t have the bias that juvenile series wouldn’t lead to Camus.”

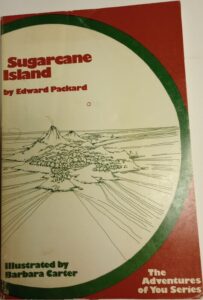

Thus when a fellow named Ray Montgomery came to her with a unique concept he called Adventures of You, he found a receptive audience. Montgomery was the co-owner of a small press called Vermont Crossroads, far removed from the glitz and glamor of Manhattan. Crossroads’s typical fare was esoteric volumes like Hemingway in Michigan and The Male Nude in Photography that generally weren’t expected to break four digits in total unit sales. A few years earlier, however, Montgomery had himself been approached by Edward Packard, a lawyer by trade who had already pitched a multiple-choice children’s book called Sugarcane Island to what felt like every other publisher in the country without success.

As he would find himself relating again and again to curious journalists in the decades to come, Packard had come up with his idea for an interactive book by making a virtue of necessity. During the 1960s, he was an up-and-coming attorney who worked long days in Manhattan, to which he commuted by train from his and his wife’s home in Greenwich, Connecticut. He often arrived home in the evening just in time to put his two daughters to bed. They liked to be told a bedtime story, but Packard was usually so exhausted that he had trouble coming up with one. So, he slyly enlisted his daughters’ help with the creative process. He would feed them a little bit of a story in which they were the stars, then ask them what they wanted to do next. Their answers would jog his tired imagination, and he would be off and running once again.

Sometimes, though, the girls would each want to do something different. “What would happen if you wrote both endings?” Packard mused to himself. A long-time frustrated writer as well as a self-described “lawyer who was never comfortable with the law,” Packard began to wonder whether he could turn his interactive bedtime stories into a new kind of book. By as early as 1969, he had invented the classic Choose Your Own Adventure format — turn to this page to do this, turn to that page to do that — and produced his first finished work in the style: the aforementioned Sugarcane Island, about a youngster who gets swept off the deck of a scientific research vessel by a sudden tidal wave and washed ashore on a mysterious Pacific island that has monsters, pirates, sharks, headhunters, and many another staple of more traditional children’s adventure fiction to contend with.

He was sure that it was “such a wonderful idea, I’d immediately find a big publisher.” He signed on with an agent, who “said he would be surprised if there were no takers,” recalls Packard. “Then he proceeded to be surprised.” One rejection letter stated that “it’s hard enough to get children to read, and you’re just making it harder with all these choices.” Letters like that came over and over again, over a period of years.

By 1975, Edward Packard was divorced from both his agent and his wife. With his daughters no longer of an age to beg for bedtime stories, he had just about resigned himself to being a lawyer forever. Then, whilst flipping through an issue of Vermont Life during a stay at a ski lodge, he happened upon a small advertisement from Crossroads Press. “Authors Wanted,” it read. Crossroads wasn’t the bright-lights, big-city publisher Packard had once dreamed of, but on a lark he sent a copy of Sugarcane Island to the address in the magazine.

It arrived on the desk of Ray Montgomery, who was instantly intrigued. “I Xeroxed 50 copies of Ed’s manuscript and took it to a reading teacher in Stowe,” Montgomery told The New York Times in 1981. “His kids — third grade through junior high — couldn’t get enough of it.” Satisfied by that proof of concept, Montgomery agreed to publish the book. Crossroads Press sold 8000 copies of Sugarcane Island over the next couple of years, a figure that was “unbelievable” by their modest standards. Montgomery was inspired to pen a book of his own in the same style, which he called Journey Under the Sea. The budding series was given the name Adventures of You — a proof that, whatever else they may have had going for them, branding was not really Crossroads Press’s strength.

Indeed, Montgomery himself was well able to see that he had stumbled over a concept that was too big for his little press. He sent the two extant books to Amy Berkower at Writers House and asked her what she thought. Having grown up on Nancy Drew, she was inclined to judge them less on their individual merits than on their prospects as a franchise in the making. A concept this new, she judged, had to have a strong brand of its own in order for children to get used to it. It would take her some time to find a publisher who agreed with her.

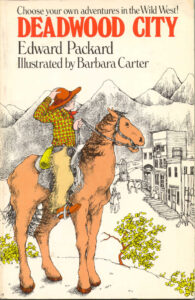

In the meantime, Edward Packard, heartened by the relative success of Sugarcane Island, was writing more interactive books. Although their names were destined to be indelibly linked in the annals of pop-culture history, Packard and Montgomery would never really be friends; they would always have a somewhat prickly, contentious relationship with one another. In an early signal of this, Packard chose not to publish more books through Crossroads. Instead he convinced the mid-list Philadelphia-based publisher J.B. Lippincott to take on Deadwood City, a Western, and Third Planet from Altair, a sci-fi tale. These served ironically to confirm Amy Berkower’s belief that there needed to be a concerted push behind the concept as a branded series; released with no fanfare whatsoever, neither sold all that well. Yet Lippincott did do Packard one brilliant service. Above the titles on the covers of the books, it placed the words “Choose your own adventures in the Wild West!” and “Choose your own adventures in outer space!” There was a brand in the offing in those phrases, even if Lippincott didn’t realize it.

For her part, Berkower was now more convinced than ever that this book-by-book approach was the wrong one. There needed to be a lot of these books, quickly, in order for them to take off properly. She made the rounds of the big publishing houses one more time. She finally found the ally she was looking for in Joëlle Delbourgo at Bantam Books. Delbourgo recalls getting “really excited” by the concept: “I said, ‘Amy, this is revolutionary.’ This is pre-computer, remember. The idea of interactive fiction, choosing an ending, was fresh and novel. It tapped into something very fundamental. I remember how I felt when I read the books, and how excited I got, the clarity I had about them.”

Seeing eye to eye on what needed to be done to cement the concept in the minds of the nation’s children, the two women drew up a contract under whose terms Bantam would publish an initial order of no fewer than six books in two slates of three. They would appear under a distinctive series trade dress, with each volume numbered to feed young readers’ collecting instinct. Barbara Marcus, Bantam’s marketing director for children’s books, needed only slightly modify the phrases deployed by J.B. Lippincott to create the perfect, pithy, and as-yet un-trademarked name for the series: Choose Your Own Adventure.

Berkower was acting as the agent of Montgomery alone up to this point. There are conflicting reports as to how and why Packard was brought into the fold. The widow of Ray Montgomery, who died in 2014, told The New Yorker in 2022 that her husband’s innate sense of fair play, plus the need to provide a lot of books quickly, prompted him to voluntarily bring Packard on as an equal partner. Edward Packard told the same magazine that it was Bantam who insisted that he be included, possibly in order to head off potential legal problems in the future.

At any rate, the first three Choose Your Own Adventure paperbacks arrived in bookstores in July of 1979. They were The Cave of Time, a new effort by Packard, written with some assistance from his daughter Andrea, she for whom he had first begun to tell his interactive stories; Montgomery’s journeyman Journey Under the Sea; and By Balloon to the Sahara, which Packard and Montgomery had subcontracted out to Douglas Terman, normally an author of adult military thrillers. Faced with an advertising budget that was almost nonexistent, Barbara Marcus devised an unusual grass-roots marketing strategy: “We did absolutely nothing except give the books away. We gave thousands of books to our salesmen and told them to give five to each bookseller and tell him to give them to the first five kids into his shop.”

The series sold itself, just as Marcus had believed it would. As The New York Times would soon write with a mixture of bemusement and condescension, it proved “contagious as chickenpox.” By September of 1980, around the time that I first discovered The Cave of Time, Publishers Weekly could report that Choose Your Own Adventure had become a “bonanza” for Bantam, which had sold more than 1 million copies of the first six volumes, with Packard and Montgomery now contracted to provide many more. A year later, eleven books in all had come out and the total sold was 4 million, with the series accounting for eight of the 25 bestselling children’s books at B. Dalton’s, the nation’s largest bookstore chain. A year after that, 10 million copies had been sold. By decade’s end, the total domestic sales of Choose Your Own Adventure would reach 34 million copies, with possibly that many or more again having been sold internationally after being translated into dozens of languages. The series was approaching its hundredth numbered volume by that point. It was a few years past its commercial peak already, but would continue on for another decade, until 184 volumes in all had come out.

Edward Packard, who turned 50 in 1981, could finally call himself an author rather than a lawyer by trade — and an astonishingly successful author at that, if not one who was likely to be given any awards by the literary elite. He and Ray Montgomery alone wrote about half of the 184 Choose Your Own Adventure installments. Packard’s prose was consistently solid and evocative without ever feeling like he was writing down to his audience, as the extract from The Cave of Time near the beginning of this article will attest; not all authors of children’s books, then or now, would dare to use a word like “phosphorescent.” If Montgomery was generally a less skilled wordsmith than Packard, and one who displayed less interest in producing internally consistent story spaces — weaknesses that I could see even as a young boy — he does deserve a full measure of credit for the pains he took to get the series off the ground in the first place. Looking back on the long struggle to get his brainstorm into print, Packard liked to quote the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer: “Every original idea is first ridiculed, then vigorously attacked, and finally taken for granted.”

Although Packard at least was always careful to make his protagonists androgynous, it was no secret that Choose Your Own Adventure appealed primarily to boys — which was no bad thing on the whole, given that it was also no secret that reading in general was a harder sell with little boys than it was with little girls. Some educators and child psychologists kvetched about the violence that was undoubtedly one of the sources of the series’s appeal for boys — in just about all of the books, it was disarmingly easy to get yourself flamboyantly and creatively killed — but Packard was quick to counter that the mayhem was all very stylized, “exaggerated and melodramatic” rather than “harsh or nasty.” “Stupid” choices were presented to you all the time, he noted, but never “cruel” ones: “You as [the] reader never hurt anyone.”

Although Packard always strained to present an “AFGNCAAP” protagonist (“Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person”), when the stars of the books were depicted on the covers they were almost always boys. Bantam explained to a disgruntled Packard that it had many years of market research showing that, while little girls were willing to buy books that showed a hero of the opposite gender on the cover, little boys were not similarly open-minded.

One had to be a publishing insider to know that this “boys series” owed its enormous success as much to the packaging and promotional skills of three women — Amy Berkower, Joëlle Delbourgo, and Barbara Marcus — as it did to the literary talents of Packard and Montgomery. Berkower in particular became a superstar within the publishing world in the wake of Choose Your Own Adventure. Incredibly, the latter became only her second most successful children’s franchise, after the girl-focused Sweet Valley High, which could boast of 54 million copies sold domestically by the end of the 1980s; meanwhile The Baby-Sitters Club was coming up fast behind Choose Your Own Adventure, with 27 million copies sold. In short, her books were reaching millions upon millions of children every single month. Small wonder that she was made a full partner at Writers House in 1988; she was moving far more books each month than anyone else there.

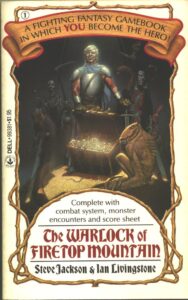

Of course, any hit on the scale of Choose Your Own Adventure is bound to be copied. And this hit most certainly was, prolifically and unashamedly. During the middle years of the 1980s, when the format was at its peak, interactive books had whole aisles dedicated to them in bookstores. Which Way?, Decide Your Own Adventure, Pick-a-Path, Twisted Tales… branders did what they could when the best brand was already taken. While Choose Your Own Adventure remained archetypal in its themes and settings, other lines were unabashedly idiosyncratic: anyone up for a Do-It-Yourself Jewish Adventure? Publishers were quick to leverage other properties for which they owned the rights, from Doctor Who to The Lord of the Rings. TSR, the maker of that other school-cafeteria sensation Dungeons & Dragons, introduced an interactive-book line drawn from the game; even this website’s old friend Infocom came out with Zork books, written by the star computer-game implementor Steve Meretzky. Many of these books were content with the Choose Your Own Adventure approach of nothing but chunks of text tied to arbitrarily branching choices, but others grafted rules systems onto the format to effectively become solo role-playing games packaged as paperback books, with character creation and advancement, a dice-driven combat system, etc. The most successful of these lines was Fighting Fantasy, a name that is today almost as well-remembered as Choose Your Own Adventure itself in some quarters.

The gamebook boom was big and real, but relatively short-lived. By 1987, the decline had begun, for both Choose Your Own Adventure and all of the copycats and expansions upon its formula that it had spawned. Although a few of the most lucrative series, like Fighting Fantasy, would join the ur-property of the genre in surviving well into the 1990s, the majority were already starting to shrivel and fall away like apples in November. Demian Katz, the Internet’s foremost archivist of gamebooks, notes that this pattern has tended to hold true “in every country” where they make an appearance: “A few come out, they become explosively popular, a flood of knock-offs are released, they reach critical mass and then drop off into nothing.” It isn’t hard to spot the reason why in the context of 1980s North America. Computers were becoming steadily more commonplace — computers that were capable of bringing vastly more flexible forms of interactive storytelling to American children, via games that didn’t require one to read the same passages of text over and over again or to toss dice and keep track of a list of statistics on paper. The same pattern would be repeated elsewhere, such as in the former Soviet countries, most of which experienced their own gamebook boom and bust during the 1990s. It seems that the arrival of the commercial mass-market publishing infrastructure that makes gamebooks go is generally followed in short order by the arrival of affordable digital technology for the home, which stops them cold.

In the United States, Bantam Books tried throughout the 1990s to make Choose Your Own Adventure feel relevant to the children of that decade, introducing a more photo-realistic art style to accompany edgier, more traditionally novelistic plots. None of it worked. In 1999, after a good twelve years of slowly but steadily declining sales, Bantam finally pulled the plug on the series. Choose Your Own Adventure became just another nostalgic relic of the day-glo decade, to be placed on the shelf next to Michael Jackson’s Thriller, a Jane Fonda workout video, and that old Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set.

Appropriately enough, the very last Choose Your Own Adventure book was written by Edward and Andrea Packard, the latter being the grown-up version of one of the little girls to whom he had once told interactive bedtime stories.

As of this writing, Choose Your Own Adventure is still around in a way, but the only real raison d’être it has left is nostalgia. In 2003, Ray Montgomery saw that Bantam Books had let the trademark for the series lapse, and formed his own company called Chooseco to try to revive it, mostly by republishing the old books that he had written himself. He met with mixed results at best. Since Montgomery’s death in 2014, Chooseco has continued to be operated by his family, who have used it increasingly as an instrument of litigation. In 2020, for example, Netflix agreed to settle for an undisclosed sum a lawsuit over “Bandersnatch,” a bold interactive episode of the critically lauded streaming series Black Mirror whose script unwisely mentioned the book series from which it drew inspiration.

A worthier successor on the whole is Choice Of Games, a name whose similarity to Choose Your Own Adventure can hardly be coincidental. Born out of a revival of the old menu-driven computer game Alter Ego, Choice Of has released dozens of digital branching stories over the past fifteen years. In being more adventurous than literary and basing themselves around broad, archetypal ideas — Choice of the Dragon, Choice of Broadsides, Choice of the Vampire — these games, which can run on just about any digital device capable of putting words on a screen, have done a fine job of carrying the spirit of Choose Your Own Adventure forward into this century. That said, there is one noteworthy difference: they are aimed at post-pubescent teens and adults — perhaps ones with fond memories of Choose Your Own Adventure — instead of children. “Play as male, female, or nonbinary; cis or trans; gay, straight, or bisexual; asexual and/or aromantic; allosexual and/or alloromantic; monogamous or polyamorous!” (Boring middle-aged married guy that I am, I must confess that I have no idea what three of those words even mean.)

Edward Packard, the father of it all, is still with us at age 94, still blogging from time to time, still a little bemused at how he became one of the most successful working authors in the United States during the 1980s. In a plot twist almost as improbable as some of his stranger Choose Your Own Adventure endings, his grandson is David Corenswet, the latest actor to play Superman on the silver screen. Never a computer gamer, Packard would doubtless be baffled by most of what is featured on this website. And yet I owe him an immense debt of gratitude, for giving me my first glimpse of the potential of interactive storytelling, thus igniting a lifelong obsession. I suspect that more than one of you out there might be able to say the same.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: Publishers Weekly of February 29 1980, September 26 1980, October 8 1982, July 25 1986, August 12 1988, December 1 1989, July 6 1990, February 23 1998; New York Times of August 25 1981; Beaver County Times of March 30 1986; New Yorker of September 19 2022; Journal of American Studies of May 2021.

Online sources include “A Brief History of Choose Your Own Adventure“ by Jake Rossen at Mental Floss, “Choose Your Own Adventure: How The Cave of Time Taught Us to Love Interactive Entertainment” by Grady Hendrix at Slate, “The Surprising Long History of Choose Your Own Adventure Stories” by Jackie Mansky at the Smithsonian’s website, and “Meet the 91-Year-Old Mastermind Behind Choose Your Own Adventure“ by Seth Abramovitch at The Hollywood Reporter. Plus Edward Packard’s personal site. And Damian Katz’s exhaustive gamebook site is essential to anyone interested in these subjects; all of the book covers shown in this article were taken from his site.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A truly incredible figure of 250 million copies sold is frequently cited for the original Choose Your Own Adventure series today, apparently on the basis of a statement released in January of 2007 by Choosco, a company which has repeatedly attempted to reboot the series in the post-millennial era. Based upon the running tally of sales which appeared in Publishers Weekly during the books’ 1980s heyday, I struggle to see how this figure can be correct. That journal of record reported 34 million Choose Your Own Adventure books sold in North America as of December 1, 1989. By that time, the series’s best years as a commercial proposition were already behind it. Even when factoring in international sales, which were definitely considerable, it is difficult to see how the total figure could have exceeded 100 million books sold at the outside. Having said that, however, the fact remains that the series sold an awful lot of books by any standard. |

|---|

Buck

September 5, 2025 at 4:50 pm

We read a Choose Your Own Adventure book as literature in elementary school (must have been the mid to late 80s). I remembered it’s name – “Die Insel der 1000 Gefahren” – and looking it up it turns out to be a translated version of “Sugarcane Island”. Apparently the “Choose Your Own Adventure” series became the “1000 Gefahren” (1000 dangers) series in German. I never felt the need to read another one, though.

Alex Freeman

September 5, 2025 at 4:58 pm

Yes, I remember reading CYOA when I was a kid. I saw them as something to read when I couldn’t get my hands on a text adventure. I too liked the freedom of text adventures more.

They now have CYOA as board games, which, in my opinion, are much better than the books:

https://www.cyoa.com/pages/choose-your-own-adventure-the-board-game?srsltid=AfmBOoqJoNLWXQSvJ7ljTiEE6Lc4UOwzI4RKKhBN_fxMzgCbQ3IgCKlg

And let’s not forget this classic:

https://www.reddit.com/r/philosophy/comments/b8gjn/if_you_agree_with_this_hypothesis_turn_to_page_72/

Tom B

September 5, 2025 at 5:46 pm

Jimmy, I also have a book-related inspiration experience from when I was a kid, right around 12-13 or so (still was not in highschool). Star Wars had come out, and I loved it, but it didn’t quite grab as hard as it did others; I was never interested in any Star Wars toys for instance. Perhaps subconciously I was reacting to the heavy fantasy elements, and I was on my way to being a hard sci-fi fan.

One day I was in my town’s public library (my dad would go downtown frequently and I would tag along, spending the time in the library) I dicovered a book titled “Spacecraft: 2000-2100 AD”, the first of Stewart Cowley’s Terran Trade Authority books, a large-format art book describing all kinds of spacecraft while telling a story of a war between Earth and their allies in Alpha Centauri against the Proxima Centaurians. This grabbed me hard, way harder than Star Wars. There was also a 2nd book, “Great Space Battles” featuring the awesome artwork of Peter Elson. These two books were just what I was looking for, and inspired my love for science fiction-based space opera rather than the fantasy type of Star Wars. I even gave a go at writing my own version, complete with planet and spacecraft guides. It was pretty crude though, I was no writer, LOL.

Michael

September 9, 2025 at 11:05 pm

Thank you, Tom. Your digression has helped me enormously. My Elementary School best friend had a copy of “Spacecraft: 2000-2100 AD”, and I used to pore over it in fascination when I visited for sleepovers (sometimes while he was fast asleep), but I could never remember an author’s name or title. I was sure, despite being a librarian, that I would go to my grave without ever finding out what it was or seeing it again, but now I have ordered it on Amazon!

S. John Ross

September 5, 2025 at 6:12 pm

Anecdotally, when I got into these around 1982, I find myself part of an active and hugely enthusiastic group of kids at my elementary school, all of us discussing the books, trading the books, loaning the books and (memorably) sometimes failing to return the loaned books … but the girls easily outnumbered the boys, maybe by as much as 2 to 1.

Either way, it was the single most popular thing I’ve ever been obsessed with, at least in terms of being surrounded by enthused peers without having to seek out a hobby enclave. Even outside the cluster of kids I was in, it seemed the whole school beyond us was also mad for them. Giddy times!

Stephen N

September 5, 2025 at 9:22 pm

I’d be remiss not to mention the wonderful Finish It! podcast here, where they read every page and ending of each book, one read each per week – they did Caves of Time quite early, and the song that begins “ You’ve hiked through Snake Canyon once before” is now stuck in my head!

https://finishitpod.com/

Leo Vellés

September 5, 2025 at 9:26 pm

Growing up as a kid in the mid 80s, I remember that this series was a big success here in Argentina. I had six or seven of this books, and ditto most of my friends. Reading and playing one of these, called ‘Who killed the president?’, I reached a point were I followed the instructions to go to some page only to find a double page illustration and no instructions to where to go from there. I think now of that as a book ‘bug’ (maybe it was only in the spanish translation?)

Keith Palmer

September 5, 2025 at 10:06 pm

There was a shelf full of Choose Your Own Adventure books in my elementary school’s library, but I have to admit hitting “bad endings” made me a less enthusiastic reader of them than some… I suppose I was taking them too seriously, or something. By the time I seemed to have outgrown that, the books had become hard to find.

On the other hand, a part of me wants to suppose a “choose your own adventure” is easier for a novice to turn into a BASIC program than even a two-word-parser text adventure built off a magazine type-in listing. I recall starting one (“survival on the moon,” as I recall) on my family’s Color Computer (and not getting very far in that seat-of-the-pants programming before keeping track of the branches overwhelmed me). The one time I remember using an Apple II at my elementary school was with a “choose your own adventure” builder called Story Tree; there, I finished something that could most charitably be called “an Indiana Jones spoof,” but didn’t get very far on my follow-up, inspired by a review in the Color Computer magazine The Rainbow of a “survive the zombie apocalypse” text adventure… A few years after that, I tried to create a branching story in HyperCard on the Macintosh SE/30 my father sometimes transported home from work, now inspired by all of the text adventures I’d read about in now-old computer magazines but never got to play (and, again, I didn’t get very far before the “combinatorial explosion” became overwhelming.)

I’m not seeking to “correct” the picture caption about the Bantam Choose Your Own Adventure artwork “always” making the protagonists boys, but I do have the feeling that with two of the earliest books, Deadwood City and The Third Planet From Altair, the protagonists look to be girls to me. I was also wondering “is Twine still a major system nowadays?” given impressions it was even more suited to a classical “choose your own adventure” structure than Choice of Games, but I suppose the point was that Choice of Games can sell its games.

arcanetrivia

September 6, 2025 at 12:48 am

Ehh… I don’t agree that they look like girls. The child on the cover of Deadwood City in this post I think is indeterminate rather than clearly a boy or girl. This version of Third Planet from Altair I think can also be read either way although I would lean towards boy if pressed. I don’t think you can have meant this version because you can barely see any features at all.

Keith Palmer

September 6, 2025 at 12:58 am

As much as I want to keep this on a “agree to disagree” level, I might clarify my thoughts by mentioning the edition of Deadwood City I was thinking of was a different one than the one pictured in this post, and my impressions were probably shaped more by the interior illustrations as a whole than just the cover illustrations.

Darkling

September 9, 2025 at 2:21 pm

I owned a handful of CYOA books as a child, and Supercomputer (#39, by Packard) is another example where (to me at least) the protagonist as depicted on the cover and in the book definitely looks like a girl – though Bantam may have been diversifying its art direction on the series by that point (or perhaps at Packard’s request on books that he wrote personally).

Rowan Lipkovits

September 5, 2025 at 10:14 pm

As a child growing up in the ’80s I enjoyed these effortlessly, like strolling through an orchard and plucking ripe fruit to snack upon as I went. They were everywhere and clearly weren’t going anywhere anytime soon! Around the turn of the century I decided that it was time to nostalgically write one myself and went casually looking in local used bookstores to locate a couple of specimens to study and diagram, only to discover to my increasing dismay that they had been pulled from the shelves and mulched in the trough of no value!

That is the boring backstory of how I went from being a juvenile gamebook appreciator to becoming an adult gamebook collector. (The story’s conclusion is that there are still plenty of them at thrift stores… these days, more often than not, the nostalgic reissues the ones on their shelves!) You think you have your finger on the pulse of a culture, but if you take a ten year break from perusing the children’s books section you may be shocked by the dramatic changes that take place there!

CJ

September 5, 2025 at 11:02 pm

My own favorite recent version of this is two books from Ryan North (of Dinosaur Comics fame, among others) which adapted a couple Shakespeare plays to “Choosable-Path Adventure” format (his own take on non-trademark-infringement).

To Be Or Not To Be: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17938417-to-be-or-not-to-be

Romeo and/or Juliet: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/27209455-romeo-and-or-juliet

The writing style is colloquial in a way that’ll be quite familiar to fans of Dinosaur Comics in particular, and I suspect it might take some getting used to for some folks, but they’re both an utter delight. The “canonical” Shakespearean choices are indicated throughout, so you can “play” through a silly version of the play itself if you like. But that does lead to some rather suboptimal endings for the characters involved.

They both let you play as various characters — in the Hamlet one, you can play as Hamlet, Ophelia, or Hamlet’s Dad’s Ghost. There’s all sorts of hidden easter eggs; books-within-books, small totally-separate stories you can only really stumble on either by chance or by thorough record-keeping, and other kinds of silliness. The Kickstarter version of To Be or Not To Be came with a skull-shaped bookmark whose “teeth” could mark multiple pages. (In practice that didn’t work so well, but it was fun regardless.)

Anyway, I highly recommend both; they remain dear favorites of mine.

I also have an inordinate amount of nostalgia for the original Choose-Your-Own-Adventures, so this one was a delight to read. Thanks!

Steph Cherrywell

September 8, 2025 at 5:50 pm

Have you read North’s more recent work, “Warp Your Own Way”, based on Star Trek: Lower Decks? It’s an absolute treat – a graphic novel which starts off as a standard CYOA-format before revealing it has a little more going on. It’s so clever that, if you liked North’s Shakespeare books, I might recommend it even if you’re not familiar with the show (though show fans will undoubtably get even more out of it.)

hcs

September 5, 2025 at 11:54 pm

Recently I ran across a few TutorText books from the ’60s. Often engineering-oriented, they are interspersed with questions to gauge understanding. You indicate your answer to a multiple choice question by turning to another page, a wrong answer can lead to a brief explanation or (rarely) a digression to correct an anticipated misunderstanding, without having to interrupt the main lesson.

I’ve been wondering to what extent “programmed instruction” materials like this might have inspired CYOA or other game books (or computer games). Maybe it was just convergent evolution, the cheapest way to publish interactivity.

Nice examples of it in this article: https://hackaday.com/2020/08/28/a-tale-of-tutor-texts/

And I checked out a 1966 programmed instruction design handbook for some background research: https://archive.org/details/peter-pipe-practical-programming

StClair

September 6, 2025 at 12:30 am

I discovered this series in middle school, when they were first coming out, and am still a fan today. Most of my favorites are from early in the run, when I was younger and most taken with them, but I have to give a nod to the delightfully meta Hyperspace, in which you actually meet Packard as well as recurring character Dr. Nera Vivaldi (for whom I named a submarine when I played Subnautica some years back).

arcanetrivia

September 6, 2025 at 12:43 am

“Play as male, female, or nonbinary; cis or trans; gay, straight, or bisexual; asexual and/or aromantic; allosexual and/or alloromantic; monogamous or polyamorous!” (Boring middle-aged married guy that I am, I must confess that I have no idea what three of those words even mean.)

I assume that you’re referring to allosexual and alloromantic; I’m struggling a bit with what the third might be but I’m going to guess aromantic. Aromantic means someone does not experience romantic love, similar to how an asexual does not experience feelings of sexual attraction. Although the prefix allo- means “other” or “different” and in scientific use usually means something is atypical (like an isomer of a chemical may be called allo-whatever), here allosexual and alloromantic mean the “standard” versions of those – someone who does experience sexual attraction or romantic love, as is assumed to be “normal”. It is marking the normally unmarked category with a term of its own, like cis (vs. trans) and allistic (vs. autistic), which uses the same all(o)- element.

Resistencia Carpincha

September 6, 2025 at 1:10 am

As Leo said in the comments, we, who grew up in Argentina in the 80s, read all the books happily. I still have a large collection and even though I moved to another country, I asked my sister to bring for my kids two of the most beloved books by me: El mistertio de la casa de piedra and El Hiperespacio.

Great series!

Ignacio

September 6, 2025 at 12:10 pm

I realize Jimmy has several followers from Argentina =)

And apparently most (all?) of us living abroad =(

Resistencia Carpincha

September 21, 2025 at 1:42 pm

Sad reality :-(.

Leo Vellés

September 6, 2025 at 8:34 pm

Resistencia Carpincha is a great name!!!! I recommend, both for you and Nacho (and to anyone that speaks spanish) to listen to the argentinian podcast Modo Historia. It is very similar to Digital Antiquarian in how they approach every era of computer games in history

Guille Crespi

September 10, 2025 at 4:12 pm

I was about to post “I’m still in Argentina and have been enjoying Jimmy’s work for many many years now!” when I saw my podcast mentioned in the thread… ¡gracias Leo! Jaja :)

Daniel A

September 6, 2025 at 3:19 am

Bravo. I experienced the same joy of discovery when I found out about the CYOA books. I couldn’t imagine reading anything else for a while. My school had 10 or 15 different books from the series, and I read them all. They started to get old after a while and, just like you, I graduated to D&D, Vampire and other pen-and-paper RPGs. I didn’t get back to them until computer games started incorporating some of dynamic narrative mechanics. The Choice of Games titles are the closest to the original, but the Telltale games (such as the excellent Walking Dead series) are what I’d call the modern version.

I maintained a lifelong fascination for dynamic narratives, culminating in my decision to take a break from my job to build a game company. My first game, Outsider (https://store.steampowered.com/app/3040110/Outsider/), is a mix of many things that you’ve covered in your blog. It’s a dynamic narrative game with a Masquerade-like puzzle hunt and a ton of references to retro gaming (and the Amiga, of course). Jimmy, if you drop by my Discord (https://discord.gg/nZSKFs9hr6) I can give you a free key. I’ll release it in under two months. :)

Keep up the great work!

Ignacio

September 6, 2025 at 4:35 am

Hi! I am so happy you chose to write about this staple of my childhood reading. It was something “missing” from the Digital Antiquarian. Thanks Mr. Maher!

My friends and I had half a dozen of these books each, and used to borrow them from one another. We also had several at our school’s library, which were usually on loan and you had to sign up on the wait list to get them once they were returned.

I believe this is a minor typo: “As any rate”, should start with ‘At’?

Ignacio

September 6, 2025 at 5:18 am

On the gender of the protagonist issue: I remember one of the CYOA books I liked the most, Secret of the Ninja by Jay Leibold (CYOA #66), placed the reader in the shoes of a female protagonist (starting with the cover illustration). Although the story is not really influenced by this, and it reads like any of the other stories with androgynous protagonists.

Jimmy Maher

September 6, 2025 at 7:00 am

We’ll go with “almost always” instead of “always” when it comes to boys on the covers. ;) Thanks!

Lars

September 6, 2025 at 8:14 am

Yes! “Sværd & Trolddom” (Fighting Fantasy) was the thing in my country (which is now yours as well). Many hours spent on that because I was a precocious reader.

Mattias Källman

September 6, 2025 at 8:40 am

Lovely essay. In my native Sweden, CYOA never became a huge cultural phenomenon, few books were translated and they weren’t very available, at least not in my small hometown. That said, I still remember borrowing a few of them from a neighbor’s kid at around age 8-9 (this was 1985-86) and devouring them, craving more.

Since very few “non-fundamental” memories of everyday life remain with me from that age, or are at least muddled, this must have been pretty fundamental.

I was already an avid reader and computer player at that point, so if this served as a gateway drug in any way, it was likely for adventure games – and learning English well enough to understand them.

A year later I dove headlong into the world of Sierra.

It’s still a bit strange to me that the format never really made the big leap to the computer back then, as an “easily digestible” alternative branch to the parser-driven adventure games.

Torbjörn Andersson

September 8, 2025 at 8:11 am

@Mattias Källman

“few books were translated and they weren’t very available, at least not in my small hometown”

I seem to remember seeing quite a few of them in book stores in Linköping. Maybe their university had something to do with that? The only series I read more than one or two books from was The Lone Wolf (“Ensamma Vargen”) by Joe Dever and The Way of the Tiger (“Tigerns väg”) by Mark Smith and Jamie Thomson. But I was surprised when I later learned how many Lone Wolf books there were, because only the first 12 were translated.

But the very first gamebook I read was “Den mystiska påsen” (approximately “The mysterious pouch”) by Betty Orr-Nilsson. It was billed as “en kors och tvärs bok” (approximately “a hither and tither book”), giving the impression that it was part of a series. But to the best of my knowledge, it was the only one. I don’t remember when I read it, but considering how fascinated I was I can’t have been very old. The Internet tells me that it was published in 1970, the year before I was born. Much later I was able to borrow it at a library, and… well, it was still fun to revisit it but with only 15 numbered sections (referred to by page number rather than section number) it was a lot more primitive than I remembered it.

As I remember it, it was about a young boy who sees someone accidentally drop a pouch before boarding the subway. The pouch turns out to contain jewels, and you find out that they are stolen. The choices then involved whether to go to the police, tell your parents, or keep it hidden for yourself. It was very much aimed at younger readers.

Of the few modern gamebooks I’ve seen, my favorite has to be Despair Inc.’s delightful satire, “Who Killed John F. Kennedy?”. It’s the first and only book in their “Lose Your Own Adventure” series. A few more titles were announced, but I don’t know if they were just there as a joke or if they really did mean to write them.

John

September 6, 2025 at 10:24 am

I somehow missed the Choose Your Own Adventure train. It’s not that I didn’t know they existed. I certainly read some. My family may have even owned one or two. It’s just that they didn’t grab the way they apparently did so many other people. I’m not entirely certain why. If I had to guess, I’d say that it’s because the average Choose Your Own Adventure is very short and isn’t really about anything. It’s just a bunch of stuff that happens. The focus is on surprise rather than plot or character. There’s nothing to get invested in. I read a lot as a kid, and, while I wouldn’t say I was a particularly discerning reader–the sheer number of Hardy Boys and Tom Swift novels I consumed would put the lie to that immediately–I suspect I wanted more from a story than the typical Choose Your Own Adventure had to offer.

glorkvorn

September 6, 2025 at 2:24 pm

I once read a remarkable book from an indie publisher which was inspired by these books: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/20488405-love-is-not-constantly-wondering-if-you-are-making-the-biggest-mistake-o . It’s superficially in that style, but not really, it’s more like an extended metaphor. The anonymous main character (and author, apparently) is stuck in a bad relationship with an alcoholic girlfriend. He alternates between trying to help her and trying to break up with her, but his choices don’t seem to matter- he’s still pulled along by the story as if he was a CYOA protagonist. Likewise, the relationship is sometimes good and sometimes bad, with problems coming up out of nowhere for insane reasons that mimic the ridiculous logic of a CYOA novel that kills you out of nowhere. He’s also a nerd who likes sci fi stories, so it it seems like he’s kind of dissociating from real life by pretending as if his real life is a sci fi pulp adventure story. As the story gets darker, he uses more and more sci fi fantasies to explain it. It’s meant to be read literally, but you can also skip pages as if it was a CYOA novel, and it sort of works either way, representing how addiction traps people in these cycles of the same problems happening over and over and losing track of time. It’s a very sad story, but with some humor and introspection that made it palatable.

Anyway I just thought it was a good example of what you said: “I didn’t have the bias that juvenile series wouldn’t lead to Camus.” This isn’t exactly Camus, but I think it shows how juvenile fantasy can be built up into something more sophisticated.

Georg

September 6, 2025 at 3:18 pm

A few months ago, I bought some used “Lone Wolf” books to try out.

My 13-year-old son – who started playing video games at the age of eight, owns a Nintendo Switch and smartphone – actually liked them, playing through six or seven of them over many hours, some of them multiple times.

I was very surprised that he got into them. But I was also surprised that they “got” me as well. There’s an element of immersion about a book about yourself that is hard to duplicate on screen, at least for me.

Torbjörn Andersson

September 8, 2025 at 8:22 am

@Georg

In the late 90s, Joe Dever gave a group of volunteers the rights to create digital editions of most of the Lone Wolf books, even including much of the illustrations. That’s how I learned there were more than just the 12 that were translated into Swedish. You can find them at https://www.projectaon.org/

I don’t think the books were in print then, though that has changed since. There are even some new books in the series, and I think slightly expanded versions of at least some of the older ones. Project Aon do not have the rights to any of that, obviously.

(If there’s ever a follow-up article to this one, I wouldn’t be surprised if they get a shout-out.)

Pelle

September 10, 2025 at 4:00 pm

There are newer translations to Swedish as well. Started some 10 years ago or so and looks like they made it to at least book 10. My local library has the first few. Lone Wolf (Ensamma Vargen) was definitely the big series here in Sweden back in the day that everyone remembers.

I never saw a Choose Your Own Adventure book back then and did not know it existed. The thing was that Äventyrsspel, that published the by far most popular RPGs in Sweden in the 1980’s, started publishing Lone Wolf and a few other series from the UK, some which they added their RPG trademarks to, even if they were not related at all. My favorites was a short horror-series of only two books, that was sold in Sweden with a big Chock logo on the cover (Chock being the Swedish version of the Chill RPG) but was really a translation of the Forbidden Gateway series (see https://gamebooks.org/Series/173/Show) that was not related at all to either Chock or Chill.

Torbjörn Andersson

September 11, 2025 at 12:19 pm

I vaguely remember seeing some horror-themed books, but couldn’t remember what they were. I’m still not sure, but the cover art for “Ondskans Gruvor” does ring a bell. Never read them, though. I did have one each of the Falcon and Fighting Fantasy books I think, but they didn’t capture my imagination the way Lone Wolf did. And again, I think only a few of the books were translated into Swedish.

Kai

September 12, 2025 at 5:49 pm

As a teenager I devoured the Lone Wolf books. I had the first twelve back then and I am sure I played through them more than once. I distinctly remember how surprised I was that the first one could be complete in little more than a dozen choices, though I never systematically explored all the possibilities or routes. It was just luck.

I even wrote my own 350 paragraph adventure and started, but never finished, an even more ambitious sequel.

To me, those kind of books did not directly compete with computer games, regular books, television or other toys. They were fun in their own right and could be as immersive as any other medium, if done well.

Chris Klimas

September 6, 2025 at 3:38 pm

Without the CYOA series, I doubt there would be Twine. Many of the story format names I picked for Twine—Jonah, Snowman, Sugarcane, Harlowe—are nods to book titles.

Whomever

September 6, 2025 at 3:48 pm

Good article! I far preferred Fighting Fantasy to CYOA. I vaguely recall there was a UK series set in a humorous King Arthur universe but I’m blanking on the name and it may be my imagination…

Pablo

September 6, 2025 at 5:56 pm

About King Arthur, you are probably talking about these:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grailquest

They had a kind of goofy silliness, but it was really fun. And in their own way, they had a very unique and sophisticated gameplay mechanic.

Whomever

September 6, 2025 at 7:19 pm

Yes! That’s it! Thanks! I really enjoyed them back in the day.

Sung

September 6, 2025 at 10:48 pm

FYI, CYOA made a bit of a comeback, or perhaps an introduction for some, with Pretty Little Mistakes:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pretty_Little_Mistakes

It came out in 2007 and was a fairly decent hit. Adult themed (about relationships), but I bet a lot of readers read that book out of the love (or familiarity) with the ones they read when they were children.

7iebx

September 7, 2025 at 3:26 am

Early in our relationship, my future wife and I did a trip to Portland, Oregon and ended up spending hours browsing the shelves at Powell’s Books. We had both been voracious CYOA fans in childhood, so when we came across Pretty Little Mistakes, the very concept of a grown up CYOA delighted us to no end. We enjoyed the rest of our time in Portland until a friend introduced us to crystal meth. We became meth addicts, crashed our car on the way home, and later died on the streets, hopelessly addicted. THE END.

(Anyone who has read Pretty Little Mistakes a few times will understand)

PVicente

September 7, 2025 at 9:35 am

Ok, a very nice article on the origin of gamebooks,it’s very interesting to see how ideas are born and take their first stumbling steps.

I loved the Fighting Fantasy books when I was a kid, they were great fun.

And speaking of Fighting Fantasy, I presume that the next entry will cover it? It has to, or else you will leave your readers with the wrong impression, that gamebooks are done and over. Fighting Fantasy (at least) it’s still a thing, with fans and authors still active (anyone feeling curious can have a look at https://www.fightingfantasy.com/), books being sold, events, and etc. And covering gamebooks (and “analog” gaming in general) without including Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone feels very, very wrong.

And we can’t forget the computer games that gamebooks inspired, starting with the 8-bit era, we are going to run into the Fighting Fantasy series here too.

usoft

September 7, 2025 at 1:31 pm

After the decline in the US and after the Fall of Berlin Wall and anti-communist revolutions of 1989, there were plenty of these translated and distributed once again with high success in former communist countries in the Eastern Europe.

I am not sure how these were licensed and who got the money, but they had the same CYOA covers. It was indeed funny for us to read them in the 1990’s, while highly interesting and novel concept, writing often felt dated. That was easy to understand as many of these were written in the 1970’s.

M. Casey

September 7, 2025 at 9:12 pm

Thanks for the timeline, the rise and fall of CYOA is interesting.

I started to read them near the peak, I guess, in the back half of the ’80s. I probably read 30 or 40; I remember my favorite being “Mountain Survival” but all these years later I couldn’t tell you why.

Later I’d read the Lone Wolf series, which tried to add in some stats and inventory elements to a CYOA-style adventure but ended up being horrifically unbalanced (as a singular d10 roll at the beginning of Book 1 would haunt you in *every single battle* for the next 17 books).

They were still fun though. And you don’t have to feel too bad about cheating a solo adventure.

Gnoman

September 7, 2025 at 9:16 pm

Not sure I really agree with this part

” It seems that the arrival of the commercial mass-market publishing infrastructure that makes gamebooks go is generally followed in short order by the arrival of affordable digital technology for the home, which stops them cold.”

By which I mean I don’t think that accessible computer games caused CYOA books to fall out of popularity. My suspicion is that they consistently fall out of popularity because they’re fundamentally a fad or trend, and all such things have a finite lifespan. 10 years of peak popularity followed by four or five years of dwindling appeal is pretty typical for a longer-lived trend.

David Yates

September 8, 2025 at 8:10 am

As a millennial, my first introduction to Choose Your Own Adventure-style books was Give Yourself Goosebumps, the interactive spin-off of RL Stine’s Goosebumps kids’ horror series. I always liked them more than the standard series, but they were harder to come by. I started reading the original Choose Your Own Adventure books later on, after finding them in second-hand bookstores.

>Although Packard always strained to present an “AFGNCAAP” protagonist (“Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person”), when the stars of the books were depicted on the covers they were almost always boys. Bantam explained to a disgruntled Packard that it had many years of market research showing that, while little girls were willing to buy books that showed a hero of the opposite gender on the cover, little boys were not similarly open-minded.

This was definitely how I felt at that age. If the character in the illustrations looked too feminine, I gave the book to my sister. I remember being annoyed that there were illustrations at all – Give Yourself Goosebumps was the superior series in my young eyes primarily because it didn’t waste valuable page space on illustrations.

Ross

September 8, 2025 at 5:54 pm

I was exactly the opposite – my favorite childrens’ books had female protagonists – but I acknowledge I was an Odd Child.

The “years of market research” thing is, I believe, now understood to be a self-fulfilling prophecy; it was widely accepted for long enough that it was impossible to get a book with a female protagonist published outside of the “ghetto” of “books for girls”, so a girl on the cover pretty much guaranteed the book was AGGRESSIVELY “girly”-coded.

Vince

September 8, 2025 at 8:47 am

Thank you Jimmy for covering this, it is definitely part of my childhood and something that was indeed my gateway drug to fiction and story-focused videogames.

It was also a discovery for me finding The Cave of Time (or, better, “La Caverna del Tempo” in the Italian translation) in a random bookshop I visited with my parents. I must have been so enthusiastic about them that they placed a mail subscription for the series. I would devour them as soon as they arrived and I must have read them 3/4 times each.

In Italy we only got about a few dozens books (from 86 to 88), with the last dozen or so weirdly pivoting to have Indiana Jones in them with the protagonist as the sidekick. I would devour them as soon as they arrived and I must have read them 3/4 times each.

I would have loved if you got in more detail of some of your favorites or your most memorable moments as you aften do with games. I will mention the secret ending in UFO 54-40 with no normal paths leading to it.

And some of the deaths are indeed memorable: in Underground Kingdom, you “jump” into a literal black-hole sun at the center of the hollow earth, in the Lost Jewels of Nabooti you are blown up by a robot-dog bomb, in The Horror of High Ridge you are forced to watch some horrible scene (not described) that you have just seen cause a friend of yours to literally die of terror.

Their literary merits might be dubious, but they could definitely fire up the imagination of a kid… the illustrations were also quite memorable.

Steph Cherrywell

September 8, 2025 at 5:57 pm

While the original Choose Your Own Adventure series isn’t the juggernaut it once was, they’re still releasing books (including graphic novels) and of course the format itself is now well-established. Aside from the Ryan North books mentioned above, Jason Shiga has Adventuregame Comics, and the fourth book of James Riley’s Story Thieves series, in which the series protagonist, a kid who can travel into books, gets trapped in one of these. All of these have puzzle/gamebook elements as well.

Incidentally, if you want to find these in a library, search ‘plot-your-own stories.’ That’s the generic term used for the subject heading, since Choose Your Own Adventure is copyrighted.

Steph Cherrywell

September 8, 2025 at 6:37 pm

Re: the mention of Packard’s “internally consistent story spaces” above — yes! When I was a kid, my biggest disappointment with these was the ones that dropped the pretense that there was a “real” world being modeled underneath. I particularly remember a haunted-house story where in one main branch the reader’s friends are revealed to have been monsters all along, luring them into a trap, where in the other branches they’re never anything but regular kids.

I guess that if you view each branch in isolation as a kind of improvised story, like Packard originally did, that’s a perfectly fine way to approach it – why shouldn’t you be able to bring in story twists that change the meaning of what came before? But I always thought of them, at their best, as explorations of a possibility space where you really saw what might have been, and “if you went to the basement first, then your friend has always secretly been a werewolf” just demolished that. It makes it all the more impressive that Packard himself was apparently better about that right from the get-go!

Ross

September 9, 2025 at 8:36 pm

I can see why it would be frustrating for some, but personally, I have a strange affection for that sort of thing. There’s a bit of an absurdist “schrodinger’s cat” thing where rather than you “playing” a story as a game, you’re doing something different where there are many *unrelated* stories existing in a superposition, and by observation, you select which one becomes “your” reality.

I think there was a lull between the waves of CYOA book popularity when I hit prime reading age? Because I feel like I first encountered CYOA books during a resurgence rather than when they were new, so I already had experience of text adventures when I got into them, which might be why I found it more interesting when a CYOA book did something that clearly different from being more of a low-tech adventure game.

Michael

September 9, 2025 at 12:00 am

Minor nitpick: so far as I can recall, TSR never used the term “gamebook” to promote their “Endless Quest” series. I have a collection of several, and the term does not appear on the covers. These were, at any rate, straightforward branching-choice narratives with no “game” elements, such as dice, stats, etc.

Jimmy Maher

September 9, 2025 at 5:31 am

Thanks!

Zed Banville

September 13, 2025 at 6:33 pm

Note that TSR, in 1985, began a series called “Super Endless Quest Adventure Gamebook”, which did incorporate RPG elements associated with gamebooks but not present in CYOA books, such as the “Endless Quest” series. TSR added the “Advanced Dungeons & Dragons” logo to the top of the third book and then dropped “Super Endless Quest” so that from the fourth book onward this series was called “Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Adventure Gamebooks”. Ultimately, 18 entries were published in this series, in just three-and-a-half years.

TSR also published 8 gamebooks related to its Marvel Super Heroes game, 6 gamebooks related to its Sniper! boardgame, and 4 entries in the Catacombs Solo Quest series that arguably were closer to D&D solo adventures than to gamebooks. While the Catacombs series refrained from using the term gamebook, the Marvel Super Heroes and Sniper! series did refer to themselves as “Adventure Gamebooks”, just like Super Endless Quest.

Mateusz Krzesniak

September 9, 2025 at 4:39 am

I think I just missed the heyday of these, but I was super into Choose Your Own Adventure and even moreso into the Endless Quest series. An upside to experiencing these on their decline was that I was able to pick up many of them in the back of my local Kay Bee Toys for super cheap and I’m sure that they led to my love for Dragonlance later on.

Looking at the links you’ve provided, I haven’t seen any of these covers in years! But it’s amazing just how many I had, it seems to be almost all of them.

f

September 9, 2025 at 11:29 pm

My friends and I first discovered CYOA books in the library of our elementary school in first grade, in 1990. While they may have already been past their prime in the U.S. at that point, in Italy (where I grew up) the ‘librigame’, as they had been dubbed, still enjoyed more than modest success. This continued throughout the early years of the 1990s, only declining towards the midpoint of that decade.

Many of the more successful series (Fighting Fantasy and Lone Wolf among them) were being translated into Italian and published by a single publishing house, Edizioni EL, with a unified – and in my opinion still quite elegant – look, featuring color-coding and individual icons to denote the various sub-series. Ideal for collecting, and probably the most dominant editions on the Italian market during those years; they were ubiquitous in bookstores, often with substantial amounts of shelf space dedicated to them.

As for my personal experience, the feature that likely most drew me to them was – branching narrative initially aside – the art. The covers boasted many colorful, striking and often lurid fantasy paintings, and the black & white illustrations on the inside ran the gamut of the monstrous, the gruesome and sometimes even the somewhat salacious. Tempting for an aspiring teenager. The stories themselves, on the flipside, were often rather testing my patience instead of drawing me in, and I often cheated my way through them in order to get to the interesting bits more quickly. I suppose the fact that videogaming was already part of my childhood, at that point, made the multiple-choice narrative feel a bit less enticing and fresh.

Today I still own a small collection of various ‘librigame’ from that era, and am quite fond of them. In particular due to their aesthetic quality, which – in contrast to their ‘gameplay’, perhaps – has aged rather gracefully :)

P.S. for anyone curious to take a look at the design of Edizioni EL’s ‘librigame’ editions: The Wikipedia article features an image of the book spines on a shelf: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Librogame.jpg

… and this Italian website dedicated to CYOA books has a gallery with most cover artworks of those editions: https://www.librogame.com/modules/myalbum/viewcat.php?cid=1

Vince

September 10, 2025 at 11:57 am

Thanks for the links!

I have somewhere at my parents’s home the Foundation game books, which I bought many years ago.

I could not find any reference to them online until now and I was starting to think it was a fake memory or something :)

Aside from them, the only other ones I read (aside from CYOA) are the Lone Wolf ones, I feel they were the most popular.

A few years ago someone created a free Android app with all the books and a convenient interface (Lone Wolf Saga), as far as I can tell it is still online and it works.

f

September 10, 2025 at 7:56 pm

Yes, Lone Wolf seemed like the series most people associated with CYOA. And yes, I remember the Asimov Foundation books – in fact, I still own one myself! It appears to be the fifth out of six (La Minaccia Del Mutante), which would also explain why I didn’t really understand what was going on when I read it, age 11 or so. From what I recall, I simply picked up that specific one because it may have been the only one available in the store, and I was familiar with some of Asimov’s short stories. And it looked cool

f

September 10, 2025 at 8:03 pm

@Vince – I forgot to add this link to the Asimov Galactic Foundation gamebooks: https://gamebooks.org/Series/939/Show

Pelle

September 10, 2025 at 4:10 pm

I think the first Tunnels & Trolls Solo Adventure, published in 1976, also deserves a mention in this context. It’s the same kind of branching gamebook as CYOA with numbered paragraphs, but it has a full RPG system attached to it, more advanced than the later Fighting Fantasy books. Tunnels & Trolls also has been kept in print and updated with new versions and more books to this day, and of course there are a few CRPGs based on it. Searched this site and saw that it has been mentioned in passing a few times, several times in the recent series of CRPG posts, but never described in any detail I think.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buffalo_Castle

Jerzy

September 11, 2025 at 8:48 pm

Thanks for the great article, Jimmy. If anyone’s interested in seeing even earlier versions of this idea, there was a 1930 book called “Consider the Consequences!” by Doris Webster and Mary Alden. It’s available to read on archive.org:

https://archive.org/details/consider-the-consequences-1930/

Keith Simpson

September 13, 2025 at 1:42 pm

This is a great article, thank you. I discovered the CYOA books as a 10 year old in 1980, living here in Sydney Australia. I would go to my local bookstore every week, hoping for a new volume, along with a new Three Investigators or Hardy Boys book. I devoured them all for a number of years.

But in 1982, my Dad bought home a TRS-80 Model 1, and that changed things. All of a sudden, a new world was opened up for me – text adventures. I was also getting older, starting high school in 1983 I began to read more adult books and CYOA books were no longer ‘cool’ for me or my friends. At some point, I donated them all to my nephew. But I’ve never forgotten these books, their amazing cover art, or the names of the authors, especially Edward Packard…I’m glad you didn’t remain a lawyer!

Tristan Miller

September 16, 2025 at 2:58 am

I was surprised to see the “Wizards, Warriors, and You” series missing from your list of CYOA knock-offs, especially given the connections you’ve drawn to Dungeons & Dragons. The books’ gimmick (apart from the second-person narration) is that at the beginning of every story, you must choose to play as either the magic-using Wizard or the weapon-wielding Warrior. Most of the encounters in the story involve choosing among a fixed set of spells or weapons detailed in appendices at the back of the book; other plot branches are determined by having the reader count the number of heads/tails in a series of coin flips. In this way each book plays very much like a condensed, solitaire D&D game, with the appendices standing in for rulebooks and coins for polyhedral dice.

The series is also notable for being written largely (and often pseudonymously) by R. L. Stine, almost a decade before he hit it big with Goosebumps.

J

September 17, 2025 at 11:04 pm

Yeah I enjoyed CYOA as a kid but graduated to WW&Y when I found one of the books in my fifth grade classroom library. I was wondering if it would be mentioned here. It was violent and gory, with plenty of horrific bad endings, so the Satanic Panic-mongers probably would not have approved.

Resistencia Carpincha

September 21, 2025 at 1:45 pm

I just wanted to thank you (again) for this post. Thanks to it I discovered that mr. Packard is still alive and active and I wrote an email to him. He answered! Very kindly I must add. Thank you for allowing me to have this!

TheWanderer

September 22, 2025 at 10:18 pm

For those wanting to try some new titles. Interactive Fiction continues to exists and being actively developed. Here are some of the top 50 games.

https://ifdb.org/viewcomp?id=1lv599reviaxvwo7

Brian Patchett

October 8, 2025 at 10:37 pm

I have a question for you all to ponder. It’s about caves.

“Adventure” was inspired by real-life cave exploration, and “Dungeons & Dragons”‘s dungeons, presumably by the Mines of Moria and similar Tolkienesque undergrounds. And “Choose Your Own Adventure” books were inaugerated with a cave story, for reasons unknown to me, but apparently not because of “Dungeons & Dragons.”

We can reasonably imagine how caves and dungeons lend themselves to game design (enclosed spaces allowing control for the game designer; clear mapping; surprises and mazes, etc.) However, the three games mentioned above, of critical importance to this blog (for one,) seem to have different points of inspiration, and are in fact three entirely different types of media. At least two of them were written by, basically, non-gamers.

Are there any other threads that I’m missing? Can we call this, on some level, a coincidence? Are caves so incredibly conducive to game design that it’s an inevitability that three quite different innovators stumbled upon it? I’d love to hear thoughtful and creative answers from all of you in the comments section.

Jimmy Maher

October 10, 2025 at 11:52 am