Years ago, [Origin Systems] released Strike Commander, a high-concept flight sim that, while very entertaining from a purely theoretical point of view, was so resource-demanding that no one in the country actually owned a machine that could play it. Later, in Ultima VIII, the company decided to try to increase their sales numbers by adding action sequences straight out of a platform game to their ultra-deep RPG. The results managed to piss just about everyone off. With Ultima IX: Ascension, the company has made both mistakes again, but this time on a scale that is likely to make everyone finally forget about the company’s past mistakes and concentrate their efforts on making fun of this one.

— Trent C. Ward, writing for IGN

Appalling voice-acting. Clunky dialog-tree system. Over-simplistic, poorly implemented combat system. Disjointed story line… A huge slap in the face for all longtime Ultima fans… Insulting and contemptuous.

— Julian Schoffel, writing from the Department of “Other Than That, It Was Great” at Growling Dog Gaming

The late 1990s introduced a new phenomenon to the culture of gaming: the truly epic failure, the game that failed to live up to expectations so comprehensively that it became a sort of anti-heroic legend, destined to be better remembered than almost all of its vastly more playable competition. It’s not as if the bad game was a new species; people had been making bad games — far more of them than really good ones, if we’re being honest — for as long as they had been making games at all. But it took the industry’s meteoric expansion over the course of the 1990s, from a niche hobby for kids and nerds (and usually both) to a media ecosystem with realistic mainstream aspirations, to give rise to the combination of hype, hubris, excess, and ineptitude which could yield a Battlecruiser 3000AD or a Daikatana. Such games became cringe humor on a worldwide scale, whether they involved Derek Smart telling us his game was better than sex or John Romero saying he wanted to make us his bitch.

Another dubiously proud member of the 1990s rogue’s gallery of suckitude — just to use some period-correct diction, you understand — was Ultima IX: Ascension, the broken, slapdash, bed-shitting end to one of the most iconic franchises in all of gaming history. I’ve loved a handful of the older Ultimas and viewed some of the others with more of a jaundiced eye in the course of writing these histories, but there can be no denying that these games were seminal building blocks of the CRPG genre as we know it today. Surely the series deserved a better send-off than this.

As it is, though, Ultima IX has long since become a meme, a shorthand for ludic disaster. More people than have ever actually played it have watched Noah Antwiler’s rage-drenched two-hour takedown of the game from 2012, in a video which has itself become oddly iconic as one of the founding texts (videos?) of long-form YouTube game commentary. Meanwhile Richard Garriott, the motivating force behind Ultima from first to last, has done his level best to write the aforementioned last out of history entirely. Ultima IX is literally never mentioned at all in his autobiography.

But, much though I may be tempted to, I can’t similarly sweep under the rug the eminently unsatisfactory denouement to the Ultima series. I have to tell you how this unfortunate last gasp fits into the broader picture of the series’s life and times, and do what I can to explain to you how it turned out so darn awful.

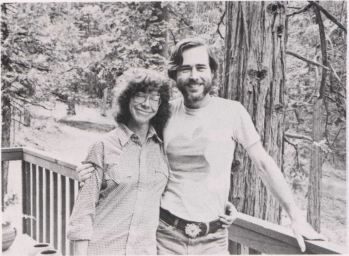

Al Remmers, the man who unleashed Lord British and Ultima upon the world, is pictured here with his wife.

The great unsung hero of Ultima is a hard-disk salesman, software entrepreneur, and alleged drug addict named Al Remmers, who in 1980 agreed to distribute under the auspices of his company California Pacific a simple Apple II game called Akalabeth, written by a first-year student at the University of Texas named Richard Garriott. It was Remmers who suggested crediting the game to “Lord British,” a backhanded nickname Garriott had picked up from his Dungeons & Dragons buddies to commemorate his having been born in Britain (albeit to American parents), his lack of a Texas drawl, and, one suspects, a certain lordly manner he had begun to display even as an otherwise ordinary suburban teenager. Thus this name that had been coined in a spirit of mildly deprecating irony became the official nom de plume of Garriott, a young man whose personality evinced little appetite for self-deprecation or irony. A year after Akalabeth, when Garriott delivered to Remmers a second, more fully realized implementation of “Dungeons & Dragons on a computer” — also the first game into which he inserted himself/Lord British as the king of the realm of Britannia — Remmers came up with the name of Ultima as a catchier alternative to Garriott’s proposed Ultimatum. Having performed these enormous semiotic services for our young hero, Al Remmers then disappeared from the stage forever. By the time he did so, he had, according to Garriott, snorted all of his own and all of the young game developer’s money straight up his nose.

The Ultima series, however, was off to the races. After a brief, similarly unhappy dalliance with Sierra On-Line, Garriott started the company Origin Systems in 1983 to publish Ultima III. For the balance of the decade, Origin was every inch The House That Ultima Built. It did release other games — quite a number of them, in fact — and sometimes these games even did fairly well, but the anchor of the company’s identity and its balance sheets were the new Ultima iterations that appeared in 1985, 1988, and 1990, each one more technically and narratively ambitious than the last. Origin was Lord British; Origin was Ultima; Lord British was Ultima. Any and all were inconceivable without the others.

But that changed just a few months after Ultima VI, when Origin released a game called Wing Commander, designed by an enthusiastic kid named Chris Roberts who also had a British connection: he had come to Austin, Texas, by way of Manchester, England. Wing Commander wasn’t revolutionary in terms of its core gameplay; it was a “space sim” that sought to replicate the dogfighting seen in Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica, part of a sub-genre that dated back to 1984’s Elite. What made it revolutionary was the stuff around the sim, a story that gave each mission you flew meaning and resonance. Gamers fell head over heels for Wing Commander, enough so to let it do the unthinkable: it outsold the latest Ultima. Just like that, Origin became the house of Wing Commander and Ultima — and in that order in the minds of many. Now Chris Roberts’s pudgy chipmunk smile was as much the face of the company as the familiar bearded mien of Lord British.

The next few years were the best in Origin’s history, in a business sense and arguably in a creative one as well, but the impressive growth in revenues was almost entirely down to the new Wing Commander franchise, which spawned a bewildering array of sequels, spin-offs, and add-ons that together constituted the most successful product line in computer gaming during the last few years before DOOM came along to upend everything. Ultima produced more mixed results. A rather delightful spinoff line called The Worlds of Ultima, moving the formula away from high fantasy and into pulp adventure of the Arthur Conan Doyle and H.G. Wells stripe, sold poorly and fizzled out after just two installments. The next mainline Ultima, 1992’s Ultima VII: The Black Gate, is widely regarded today as the series’s absolute peak, but it was accorded a surprisingly muted reception at the time; Charles Ardai wrote in Computer Gaming World how “weary gamers [are] sure that they have played enough Ultima to last them a lifetime,” how “computer gaming needs another visit to good old Britannia like the movies need another visit from Freddy Kreuger.” That year the first-person-perspective, more action-oriented spinoff Ultima Underworld, the first project of the legendary Boston-based studio Looking Glass, actually sold better than the latest mainline entry in the series, another event that had seemed unthinkable until it came to pass.

Men with small egos don’t tend to dress themselves up as kings and unironically bless their fans during trade shows and conventions, as Richard Garriott had long made a habit of doing. It had to rankle him that the franchise invented by Chris Roberts, no shrinking violet himself, was by now generating the lion’s share of Origin’s profits. And yet there could be no denying that when Electronic Arts bought the company Garriott had founded on September 25, 1992, it was primarily Wing Commander that it wanted to get its hands on.

So, taking a hint from the success of not only Wing Commander but also Ultima Underworld, Garriott decided that the mainline games in his signature series as well had to become more streamlined and action-oriented. He decided to embrace, of all possible gameplay archetypes, the Prince of Persia-style platformer. The result was 1994’s Ultima VIII: Pagan, a game that seems like something less than a complete and total disaster today only by comparison with Ultima IX. Its action elements were executed far too ineptly to attract new players. And as for the Ultima old guard, they would have heaped scorn upon it even if it had been a good example of what it was trying to be; their favorite nickname for it was Super Ultima Bros. It stank up the joint so badly that Origin chose toward the end of the year not to even bother putting out an expansion pack that its development team had ready to go, right down to the box art.

The story of Ultima IX proper begins already at this fraught juncture, more than five years before that game’s eventual release. The team that had made Ultima VIII was split in two, with the majority going to work on Crusader: No Remorse, a rare 1990s Origin game that bore the name of neither Ultima nor Wing Commander. (It was a science-fiction exercise that wound up using the Ultima VIII engine to better effect, most critics and gamers would judge, than Ultima VIII itself had.) Just a few people were assigned to Ultima IX. An issue of Origin’s internal newsletter dating from February of 1995 describes them as “finishing [the] script stage, evaluating technology, and assembling a crack development team.” Origin programmer Mike McShaffry:

Right after the release [of Ultima VIII], Origin’s customer-service department compiled a list of customer complaints. It weighed about ten pounds! The Ultima IX core team went over this with a fine-toothed comb, and we decided along with Richard that we should get back to the original Ultima design formula. Ultima IX was going to be a game inspired by Ultimas IV and VII and nothing else. When I think of that game design I get chills; it was going to be awesome.

As McShaffry says, it was hoped that Ultima IX could rejuvenate the franchise by righting the wrongs of Ultima VIII. It would be evolutionary rather than revolutionary, placing a a modernized gloss on what fans had loved about the games that came before: a deep world simulation, a whole party of adventurers to command, lots and lots of dialog in a richly realized setting. The isometric engine of Ultima VII was re-imagined as a 3D space, with a camera that the player could pan and zoom around the world. “For the first time ever, you could see what was on the south and east side of walls,” laughs McShaffry. “When you walked in a house, the roof would pop off and you could see inside.” Ultima IX was also to be the first entry in the series to be fully voice-acted. Origin hired one Bob White, an old friend with whom Richard Garriott had played Dungeons & Dragons as a teenager, to turn Garriott’s vague story ideas into a proper script for the voice actors to perform.

Garriott himself had been slowly sidling back from day-to-day involvement with Ultima development since roughly 1986, when he was cajoled into accepting that the demands of designing, writing, coding, and even drawing each game all by himself had become unsustainable. By the time that Ultima VII and VIII rolled around, he was content to provide a set of design goals and some high-level direction for the story only, while he busied himself with goings-on in the executive suite and playing Lord British for the fans. This trend would do little to reverse itself over the next five years, notwithstanding the occasional pledge from Garriott to “discard the mantle of authority within even my own group so I can stay at the designer level.” (Yes, he really talked like that.) This chronic reluctance on the part of Ultima IX’s most prominent booster to get his hands dirty would be a persistent issue for the project as the corporate politics surrounding it waxed and waned.

For now, the team did what they could with the high-level guidance he provided. Garriott had come to see Ultima IX as the culmination of a “trilogy of trilogies.” Long before it became clear to him that the game would probably mark the end of the series for purely business reasons, he intended it to mark the end of an Ultima era at the very least. He told Bob White that he wanted him to blow up Britannia at the conclusion of the game in much the same way that Douglas Adams had blown up every possible version of the Earth in his novel Mostly Harmless, and for the same reason: in order to ensure that he would have his work cut out for him if he decided to go back on his promise to himself and try to make yet another sequel set in Britannia. By September of 1996, White’s script was far enough along to record an initial round of voice-acting sessions, in the same Hollywood studio used by The Simpsons.

But just as momentum seemed to be coalescing around Ultima IX, two other events at Origin Systems conspired to derail it. The first was the release of Wing Commander IV: The Price of Freedom in April of 1996. Widely trumpeted as the most expensive computer game yet made, the first with a budget that ran to eight digits, it marked the apex of Chris Roberts’s fixation on making “interactive movies,” starring Mark Hamill of Star Wars fame and a supporting cast of Hollywood regulars acting on a real Hollywood sound stage. But it resoundingly failed to live up to Origin’s sky-high commercial expectations for it; at three times the cost of Wing Commander III (which had also featured Hamill), it generated one-third as many sales. This failure threw all of Origin Systems into an existential tizzy. Roberts and few of his colleagues left after being informed that the current direction of the Wing Commander series was financially untenable, and everyone who remained behind wondered how they were going to keep the proverbial lights on now that both of Origin’s flagship franchises had fallen on hard times. The studio went through several rounds of layoffs, which deeply scarred the communal psyche of the survivors; Origin would never fully recover from the rupture, never regain its old confident swagger.

Partially in response to this crisis, another project that bore the name of Ultima saw its profile elevated. Ultima Online was to be the fruition of a dream of a persistent multiplayer fantasy world that Richard Garriott had been nursing since the 1980s. In 1995, when rapidly spreading Internet connectivity combined with the latest computer hardware were beginning to make the dream realistically conceivable, he had hired Raph and Kristen Koster, a pair of Alabama graduate students who were stars of the textual-MUD scene, to come to Austin and build a multiplayer Britannia. Ultima Online had at first been regarded more as a blue-sky research project than a serious effort to create a money-making game; it had seemed the longest of long shots, and was barely tolerated on that basis by the rest of Origin and EA’s management.

But the collapse of the industry’s “Siliwood” interactive-movie movement, as evinced by the failure of Wing Commander IV, had come in the midst of a major commercial downturn for single-player CRPGs like the traditional Ultimas as well. Both of Origin’s core competencies looked like they might not be applicable to the direction that gaming writ large was going. In this terrifying situation, Ultima Online began to look much more appealing. Online gaming was growing apace alongside the young World Wide Web, even as the appeal of Ultima Online’s new revenue model, whereby customers could be expected to pay once to buy the game in a box and then keep paying every single month to maintain access to the online multiplayer Britannia, hardly requires further clarification. Ultima Online, it seemed, might be the necessary future for Origin Systems, if it was to have a future at all. These incipient ideas were given a new impetus over the last four months of 1996, when two other massively-multiplayer-online-role-playing games — a term coined by Richard Garriott — were launched to a cautiously positive reception. This relative success came even though neither 3DO’s Meridian 59 nor Sierra’s The Realm was anywhere near as technically and socially sophisticated as the Kosters intended Ultima Online to be.

By the beginning of 1997, the Ultima Online developers were closing in on a wide-scale beta test, the last step before their game went live for paying customers. Rather cheekily, they asked the fans who had been following their progress closely on the Internet to pony up $5 each months in advance for the privilege of becoming their guinea pigs; cheeky or not, tens of thousands of fans did so. This evidence of pent-up demand convinced the still-tiny team’s managers to go all-in on their game. In March of 1997, the nine Ultima Online people were moved into the office space currently occupied by the 23 people who were making Ultima IX. The latter were ordered to set aside what they were working on and help their new colleagues get their MMORPG into shape for the beta test. In the space of a year, Ultima Online had gone from an afterthought to a major priority, while Ultima IX had done precisely the opposite. Although both games were risky projects, it looked like Ultima Online might be the better match for where gaming was going.

The conjoined team got Ultima Online to beta that summer and into boxes in stores that September, albeit not without a certain degree of backbiting and infighting. (The Ultima Online people regarded the Ultima IX people as last-minute jumpers on their bandwagon; the Ultima IX people were equally resentful, suspecting — and not without some justification — that their own project would never be restarted, especially if the MMORPG took off as Origin hoped it would.) Although dogged throughout its early years by technical issues and teething problems of design, the inevitable niggles of a pioneer, Ultima Online was soon able to attract a fairly stable base of some 90,000 players, each of whom paid Origin $10 per month to roam the highways and byways of Britannia with others.

It became a vital revenue stream for a studio that otherwise didn’t have much of anything going for it. The same year as Ultima Online’s launch, Wing Commander: Prophecy, an attempt to reboot the series for this post-Chris Roberts, post-interactive-movie era, was released to sales even worse than those of Wing Commander IV, marking the anticlimactic end of the franchise that had been the biggest in computer gaming just a few years earlier. Any petty triumph Richard Garriott might have been tempted to feel at having seen his Ultima outlive Wing Commander was undermined by the harsh reality of Origin’s plight. The only single-player games now left in development at the incredible shrinking studio were the Jane’s Longbow hardcore helicopter simulations, entries in yet another genre that was falling on hard commercial times.

Electronic Arts was taking a more and more hands-on role as Origin’s fortunes declined. A pair of executives named Neil Young and Chris Yates had been parachuted in from the Silicon Valley mother ship to become Origin’s new General Manager and Chief Technical Officer respectively. Much to the old team’s surprise, they opted to restart Ultima IX in late 1997. They read the massive success of the CRPG-lite Diablo as a sign that the genre might not be as dead to gamers as everyone had thought, especially if it was given an audiovisual facelift and, following the example of Diablo, had its gameplay greatly simplified. A producer named Edward Alexander Del Castillo was hired away from Westwood Studios, where he had been in charge of the mega-selling Command & Conquer series of real-time-strategy games. If anyone could figure out how to make the latest single-player Ultima seem relevant to fans of more recent gameplay paradigms, it ought to be him.

What with the ongoing layoffs and other forms of attrition, fewer than half of the 23 people who had been working on Ultima IX prior to the Ultima Online interregnum returned to the project. Those who did sifted through the leavings of their earlier efforts, trying to salvage whatever they could to suit Del Castillo’s new plans for the project. He re-imagined the game into something that looked more like the misbegotten Ultima VIII than the hallowed Ultima VII. The additional party members were done away with, as was the roving camera, and the visuals and interface came to mimic third-person action games like the hugely popular Tomb Raider. Del Castillo convinced Richard Garriott to come up with a new story outline in which Britannia didn’t get destroyed, an event which might now read as confusing, given that people would presumably still be logging into Ultima Online to adventure there after this single-player game’s release. In the new script, as fleshed out once again by Bob White, the player’s goal would be to become one with the villainous Guardian, who would turn out to be the other half of himself, and rise as one being with him to a higher plane of existence; thus the “ascension” of the eventual subtitle. It felt like the older games in the way it flirted with spirituality, for all that it did so a bit clumsily. (Garriott stated in a contemporaneous interview that “I’m enamored with Buddhism right now,” as if it was a catchy tune he’d heard on the radio; this isn’t the way spirituality is supposed to work.)

In May of 1998, Origin brought the work in progress to the E3 trade show. It did not go well. The old-school fans were appalled by the teaser video the team brought with them, featuring lots of blood-splattered carnage choreographed to a thrash-metal soundtrack, more DOOM than Ultima. Del Castillo got defensive and derisive when confronted with their criticisms, making a bad situation worse: “Ultimas are not about stick men and baking bread. Ultimas are about using the computer as a tool to enhance the fantasy experience. To take away the clumsy dice, slow charts and paper and give you wonderful gameplay instead. They were never meant to mimic paper RPGs; they were meant to exceed them.” In addition to being a straw-man argument, this was also an ahistorical one: like all of the first CRPGs, Richard Garriott’s first Ultima games had been literal, explicit attempts to put the tabletop Dungeons & Dragons game he loved on a computer. Internet forums and Usenet message boards burned with indignation in the weeks and months after the show.

Those who could abandoned the increasingly dysfunctional ship. Bob White bailed for John Romero’s new company Ion Storm, where he became a designer on Deus Ex. Then Del Castillo left, citing vague “philosophical differences” with Richard Garriott, to start his own studio Liquid Entertainment. Lead programmer Bill Randolph recalls the last words Del Castillo said to him on the day he left: “They don’t care about the game. They’re just going to shove it out the door unfinished.”

Garriott announced, not for the first time, that he intended to step in and take a more hands-on role at this juncture, but that never amounted to much beyond an unearned “Director” credit. “You know, he had a lot of other obligations, and he had a lot going on, and a lot of other interests that he was pursuing too,” says Randolph by way of apologizing for his boss. Be that as it may, Garriott’s presence on the org chart but non-presence in the office resulted in a classic power vacuum; everyone could see that the game was shaping up to be hot garbage, but no one felt empowered to take the steps that were needed to fix it. Turnover continued to be a problem as Origin continued to take on water. Few of the people left on the team had any experience with or emotional connection to the previous single-player Ultima games.

Del Castillo’s ominous prophecy came true on November 26, 1999, after a frantic race to the bottom, during which the exhausted, demoralized team tried to hammer together a bunch of ill-fitting fragments into some semblance of a playable game in time for EA’s final deadline. They met the deadline — what other choice did they have? — but the playable game eluded them.

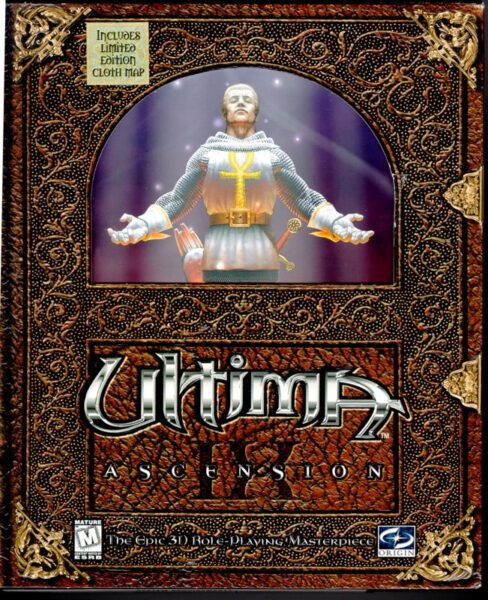

I don’t want to spend a lot of time here excoriating Ultima IX in detail, the way I did Omikron: The Nomad Soul in my very last article. I nominated Omikron for Worst Game of 1999, but Ultima IX has run away with that prize. Although I found Omikron to be deliriously lousy, it was at least lousy in a somewhat interesting way, the product of a distinctive if badly misguided vision. Ultima IX, alas, doesn’t have even that much going for it. Whatever original creative vision it might once have evinced has been so thoroughly ground away by outside pressures and corporate interference that it’s not even fun to make fun of. As far as kind words go, all I can come up with is that the box looks pretty good — a right proper Ultima box, that is — and some of the landscape vistas are impressive, as long as you don’t spoil the experience by trying to do anything as you’re looking at them. Everything else is pants.

Imagine the worst possible implementation of every single thing Ultima IX tries to do and be, and you’ll have a reasonably good picture of what this game is like. Even 26 years later, it remains a technical disaster: crashing constantly, full of memory leaks that gradually degrade performance as you play. Characters and monsters have an unnerving habit of floating in the air, their feet at the height of your eyes; corpses — and not undead ones — sometimes inexplicably keep on fighting instead of staying put on the ground (or in mid-air, as the case may be). These things ought to be funny in a “so bad it’s good” kind of way, but somehow they aren’t. Absolutely nothing about this game is entertaining — not the cutscenes that were earmarked for an earlier incarnation of the script only to be shoehorned into this one, not the countless other parts of the story that just don’t make any sense. Nothing feels right; the physics of the world are subtly off even when everything is ostensibly working correctly. The fixed camera always seems to be pointing precisely where you don’t want it to, and combat is just bashing away on the mouse button, an action which feels peculiarly disconnected from what you see your character doing onscreen.

Of course, one can make the argument that Ultima wasn’t really about combat even in its best years; Ultima VII’s combat system is almost as bad as this one, and that hasn’t prevented that game from becoming the consensus choice for the peak of the entire series. What well and truly pissed off the series’s hardcore fan base back in the day was how badly this game fails as an Ultima. A game that was once supposed to correct the ill-advised misstep that had been Ultima VIII and mark a return to the franchise’s core values managed in the end to feel like even more of a betrayal than its predecessor. This final installment of a series famous for the freedom it affords its player is a rigidly linear slog through underwhelming plot point after underwhelming plot point. Go to the next city; perform the same set of rote tasks as in the last one; rinse and repeat. If you try too hard to do something other than that which has been foreordained for you, you just end up breaking the game and having to start over.

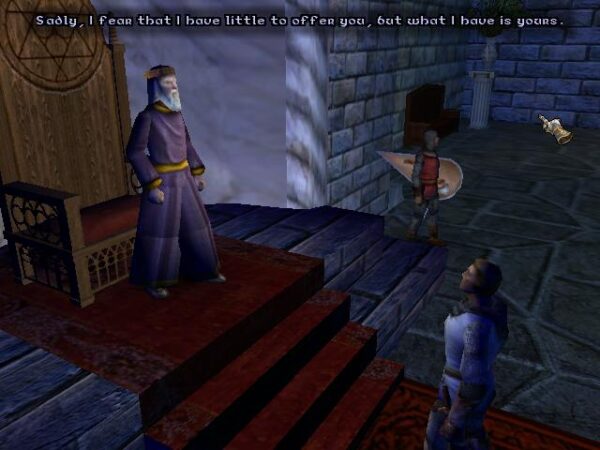

And yet it’s not as if Ultima IX doesn’t try to exploit its heritage. In fact, no Ultima that came before was as relentlessly self-referential as this one. You create your character by answering questions from a gypsy fortuneteller, like in the iconic opening of Ultima IV. The plot hinges on yet another corruption of the Virtues, like in the fourth, fifth, and sixth games. You visit Lord British in his castle, like in every Ultima ever. There you find a newly constructed museum celebrating your exploits, from your defeat of the evil wizard Mondain in Ultima I to your recent difficulties with the Guardian, the overarching villain of this third trilogy of trilogies. The foregrounded self-referentiality quickly becomes much, much too much; it gives the game a past-its-time, sclerotic feel that must have thoroughly nonplussed any of the new generation CRPG players, weaned on Baldur’s Gate and Might and Magic VI and VII, who might have been unwise enough to pick this game up instead of Planescape: Torment, its primary competition that Christmas season of 1999. Ultima IX is like that boring old man who can’t seem to shut up about all the cool stuff he used to get up to.

But at the same time, and almost paradoxically, Ultima IX is utterly clueless about its heritage, all too obviously the product — and I use that word advisedly — of people who knew Ultima only as a collection of tropes. I don’t really mean all the little details that it gets wrong, which the fans have, predictably enough, cataloged at exhaustive length. When it comes to questions of continuity, I’m actually prepared to extend quite a lot of slack to a series that went from games written by a teenager all by himself in his bedroom to multi-million-dollar productions like this one over the course of almost twenty years of tempestuous technical and cultural evolution in the field of gaming. Rather than the nitpicky details, it’s the huge, fundamental things that this game and its protagonist seem not to know that flummox me. (Remember, the official line is that the Avatar is the same guy through all nine mainline Ultima games and all of the spinoffs to boot.) At one point in this game, the Avatar encounters the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom, the object around which revolved the plot of Ultima IV, probably the best-remembered and most critically lauded entry in the series except for Ultima VII. “The Codex of Ultimate Wisdom?” he repeats in a confused tone of voice, as if he’s sounding out the words as he goes. As Noah Antwiler said in my favorite quip from his video series, this is like the pope asking someone if she happens to know what this Bible thing is that the priests around him keep banging on about.

The most famous meme that came out of Antwiler’s videos is another example of the Avatar’s slack-jawed cluelessness. “What’s a paladin?” he asks the first person he meets in Trinsic, the town of Honor which he has visited many times in the course of his questing. You have to hear him say it, in the voice of a bored television announcer, to fully appreciate it. (Like everything else in this game, the voice-acting, which had to be redone at the last minute to fit the new script, is uniformly atrocious, the output of people who all too clearly have no idea what they’re saying or why they’re saying it. Lord British sounds like a doddering old fool, inadvertently mirroring the state of the series by this point.)

You can make excuses for the existence of some of this stuff, if not the piss-poor execution. Origin obviously felt a need to make Ultima IX comprehensible and accessible to new players, coming as it did fully five and a half years after its predecessor. Lots of people had joined the gaming hobby over those years, and some of the old-timers had left it. But such excuses didn’t keep the people who were most invested in the series from seeing it as a slap to the face. “What’s a paladin?” indeed. They felt as if a treasured artifact of their childhood had been stolen and desecrated by a bunch of philistines who didn’t know an ankh from a hole in the ground. Origin ended up with the worst of all worlds: a game that felt too wrapped up in its lore to live and breathe for newcomers, even as it felt insultingly dumbed-down to the faithful who had been awaiting it with bated breath since 1994.

Any lessons we might hope to draw from this fiasco are, much like the game itself, almost too banal to be worth discussing. But, for the record:

- No game can be all things to all people.

- Development teams need a clear leader with a clear vision.

- Checking off a list of bullet points sent down from marketing does not a good game make.

- When the design goals do change radically, it’s often better to throw everything out and start over from scratch than to keep retro-fitting bits and pieces onto the Frankenstein’s monster.

- It’s better to release a good game late than a bad game on time.

Beginning with Ultima VIII, the series had begun to chase trends rather than to blaze its own trails. This game, despite all the good intentions with which it was begun, doubled down on that trend in the end. Even if the execution had been better, it would still have felt like a pale shadow of the earlier Ultima games, the ones that had the courage of their convictions. It’s not just a bad game; it’s a dull, soulless one too. If the Ultima series had to go out on a sour note, it would have been infinitely nicer to see it blow itself up in some sort of spectacular failure rather than ending in this flaccid fashion. Origin’s Neil Young could have learned a lesson from his musical namesake: “It’s better to burn out than to fade away.”

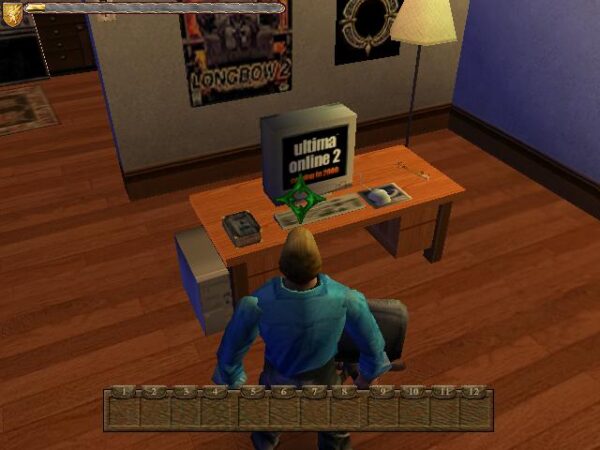

You start out in your house on Earth, even though this directly contradicts the ending of Ultima VIII.

The gypsy fortuneteller makes a return to help you choose a class and send you on your way to Britannia.

As you have probably surmised, Ultima IX did not do well in the marketplace. There was never any serious discussion of continuing the single-player series after it was greeted with bad reviews and worse sales. In fact, it managed not only to kill the series to which it belonged but for all intents and purposes the studio that had always been so closely identified with it as well. It was the last single-player game ever to be completed at Origin Systems.

Officially speaking, Origin continued to exist for another four years after it, but only to service Ultima Online. Right about the same time that Ultima IX was reaching stores, that game was actually ceding its crown as the biggest MMORPG of all to EverQuest. Nevertheless, in a bull market for MMORPGs in general amidst the first wave of widespread broadband-Internet adoption, Ultima Online’s raw numbers still increased, reaching as many as 250,000 subscribers in early 2003. But the numbers started to go the other way thereafter as the MMORPG field became ever more crowded with younger, slicker entrants. Inevitably, there came a day in February of 2004 when it no longer made sense to EA to keep an office open in Austin just to support a single aged and declining online game. And so the story of Origin Systems came to its belated, scarcely noticed end, a decade after its best years were over.

By then, Richard Garriott was long gone; he had left Origin in March of 2000. His subsequent career did little to prove that his dilettantish approach to the later Ultima games had been a fluke. He dabbled in gaming only in fits and starts, most notably by lending his name to two more MMORPGs, both of which proved disappointing. As also happened with his old Origin sparring partner Chris Roberts, an unfortunate whiff of grift came to attach itself to him; I tend to think that it’s born more of carelessness in his choice of projects and associates than guile in his case, but that doesn’t make it any more pleasant to witness. Shroud of the Avatar, his Kickstarter-funded would-be seconding coming of Ultima Online, petered out in the late 2010s in broken promises and serious ethical questions about its suddenly pay-to-win focus. In more recent years, he has talked up an MMORPG based on blockchain technology (Lord help us!) that now appears unlikely to turn into anything at all. It seems abundantly plain that his heart hasn’t really been in making games for many years now. One hopes he will finally be content just to retire from an industry that has long since passed him by.

There’s something a little sad about watching Richard Garriott play the hits in his Lord British get-up as he closes in on retirement age.

However cheerless of a conclusion it might be, this very last article about Richard Garriott and Ultima marks a milestone for these histories. I’ve genuinely loved some of the Ultima games I’ve played these past fifteen years: Ultima I for its irrepressible teenage-Dungeonmaster enthusiasm, Ultima VII for its literary and thematic audacity, Ultima Underworld for its bold spirit of innovation. Most of all, I found myself loving the rollicking Worlds of Ultima games, two of the least played, least remembered entries in the series. (By all means, go check them out if you haven’t tried them!) As for the rest — at least the ones that came before Ultima VIII — I can see their place in history and see why others love or once loved them, even if I do also see them more as artifacts of their time than timeless.

But such carping is almost irrelevant to the cultural significance of Ultima. Richard Garriott had a huge impact on thousands upon thousands of people through Ultima IV in particular, a game which caused many of its young players to think seriously about the nature of morality and their place in the world for the very first time. Coming from a fellow not much older than they were, raised on the same sci-fi flicks and fantasy fiction that they were consuming, moral philosophy felt more real and relevant than it did when it was taught to them in school. Small wonder that so many of them still adore him for what his work meant to them all those years ago, still rush to defend him whenever a curmudgeon like myself points out his feet of clay. And that’s fine; we need to be clear-eyed about things sometimes, but at other times we just need our heroes.

So, let us bid a fond farewell to Richard Garriott — or, if you insist, Lord British, the virtuous king of Britannia. His legacy as one of gaming’s greatest visionaries is secure.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Explore/Create: My Life in Pursuit of New Frontiers, Hidden Worlds, and the Creative Spark by Richard Garriott with David Fisher; Through the Moongate: The Story of Richard Garriott, Origin Systems Inc. and Ultima, in two parts by Andrea Contato; Ultima IX: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide; Online Game Pioneers at Work by Morgan Ramsay. Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of December 6 1991, February 10 1995, and September 20 1996; Next Generation of March 1998; Computer Gaming World of September 1992 and February 2000.

Online sources include “Ultima IX Nitpicks on the Tapestry of the Ages” on Hacki’s Ultima Page; Noah Anwiler’s video lacerations of Ultima IX; the Ultima Codex’s “Development History of Ultima IX“; Ultima Codex interviews with Mike McShaffry and Bill Randolph; an old GameSpot interview with McShaffry; Julian Schoffel’s Ultima IX retrospective for Growling Dog Games; a December 1999 group chat with some of the Ultima IX team; Desslock’s October 1998 interview with Richard Garriott for GameSpot; Trent C. Ward’s review of Ultima IX for IGN; KiraTV’s documentary about Shroud of the Avatar (but do be aware that the first part of this video uncritically regurgitates the legend rather than the reality Richard Garriott’s pre-millennial career).

Where to Get It: Ultima IX: Ascension is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.