Imagine a card game where there are hundreds of cards, with more being made all the time. Some cards are rare and some are common. You build a deck with whatever cards you want. You have no idea what’s in your opponent’s deck. And then you duel.

— Richard Garfield to Peter Adkison, 1991

Most revolutions have humble origins. Magic: The Gathering, the humble little card game that upended its industry in the 1990s, is no exception. It began with an ordinary-seeming fellow from the American heartland by the name of Peter Adkison.

Adkison grew up in rural Idaho in a family of Seventh Day Adventists, an idiosyncratic branch of evangelical Christianity. When not in church, the household played card and board games of all descriptions, a hobby for which the dark, snowy winters of their part of the country left ample time.

Adkison had moved to eastern Washington State to attend Walla Walla College when the Dungeons & Dragons craze of the early 1980s hit. Unfortunately, the game was soon banned from his college, itself a Seventh Day Adventists institution, because it was believed to have ties to Satanism. But fortunately, his mother, who had recently left both his father and the faith, gave him and his friends a safe space to play in her basement during vacations and holidays.

In 1985, Adkison graduated with a degree in computer science and went to work for Boeing in Seattle. Half a decade later, having grown disenchanted with the humdrum day-to-day of corporate aerospace engineering, he founded a would-be games publisher called Wizards of the Coast in his own basement. Looking for the right ticket into the hobby-game industry, he posted an open call on Usenet for designers who might be willing to sign on with a new and unproven company such as his. It was answered by two graduate students in mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania, whose names were Mike Davis and Richard Garfield. They all agreed to meet in person on August 17, 1991, in Portland, Oregon, the home of Garfield’s parents.

Adkison realized quickly at that meeting that the specific design the pair had come to pitch to him was untenable for Wizards of the Coast, at least at this juncture. Called Robo Rally, it portrayed a madcap race by out-of-control robots across a factory floor, the players continually “programming” them a few moves ahead of time to deal with whatever obstacles looked like they were coming next. The game was (and is) pretty brilliant, but it required far too many bobs and thingamajigs in the box to be practical under Adkison’s current budgetary constraints.

Nevertheless, he was impressed by the pair — especially by Garfield, a PhD student in the field of combinatorics, who seemed the more committed, passionate, and creative of the two. Mind you, it wasn’t that he cut a particularly rousing figure by conventional metrics. “Then, as now,” says Adkison, “he wore mismatched socks, had strange bits of thread and fabric hanging from parts of his clothing, and generally looked like someone who had just walked into the Salvation Army [Store] and grabbed whatever seemed colorful.” It was Garfield’s sheer love of games — all kinds of games — that drew Adkison in: “His vision was clear, and went to the heart of gaming. He was looking for entertainment, social interaction, mental exercise, creativity, and challenge. I suddenly felt stupid, remembering the time I had refused to play Pictionary, even though I knew I would probably enjoy it.”

Still, Adkison recognized that he had no choice but to let this weirdly inspiring new acquaintance down as gently as possible: It’s not your game design, it’s my lack of the resources to do it justice. Whereupon Garfield spoke the words that would change both their lives forever: “If you don’t want Robo Rally, what do you want? Describe a game concept — any concept — and I’ll design a game around it for you.”

Adkison was taken aback. He had been hoping to serendipitously stumble upon the ideal game, and now he had the chance to have one designed to order. What made the most sense for getting his company off the ground? It ought to be something small and simple, something cheap and easy to produce. Perhaps… yes! A card game would be ideal; that way, there would be no need for the manufacturing complications of boards or dice or injection-molded plastic figurines. And yet it could still be colorful and exciting to look at, if he brought in some good illustrators for the cards. It could be a snack-sized game for two people that was playable in twenty minutes or less, perfect for filling those down times around the table while waiting for the rest of the group to show up, or waiting for that week’s designated away team to return with the pizzas. There always seemed to be a shortage of that kind of game in the hobbyist market, where everybody wanted to go epic, man all the time. It could be displayed next to the cash register at gaming stores as a potential impulse buy, could become a little stocking stuffer for that special gamer in your life. Such a game would be a splendid way of getting Wizards of the Coast off the ground. Once that was accomplished, there would be plenty of time for the likes of Robo Rally.

A nodding Richard Garfield took it all in and promised to think about it.

They all met up again at a Seattle gaming convention a week later. Here Adkison learned that, true to his word, Garfield had indeed been thinking about his requested snack-sized card game. In fact, he’d been thinking rather hard. He proposed a game in which the players would be wizards who engaged in a duel, summoning minions to do their bidding and hurling spells at one another. Thematically speaking, it wasn’t exactly groundbreaking in a gaming milieu that had J.R.R. Tolkien and Gary Gygax as its patron saints. Nevertheless, as Garfield expanded on his concept, Adkison’s eyes kept getting wider. And when he was done, Adkison ran outside to the parking lot so that he could whoop for joy without inhibition. Garfield’s idea was, he was convinced, the best one to come along in the tabletop space since Dungeons & Dragons. He could already smell the money it was going to make all of them.

The true genius of Garfield’s idea — the reason that Adkison knew it could make him rich — was ironically external to the core gameplay loop that is the alpha and omega of most games. That said, that loop needed to be rock solid for the rest of the magic of Magic: The Gathering to happen. And this it most certainly was. I should take a moment to go over it here before I continue my story.

You Can Do Magic: A Very (Very, Very) Brief Introduction

While it is possible for more than two players to participate in a game of Magic, we’ll play it today as a one-on-one duel, by far its most common incarnation in its glory days of the 1990s. Indeed, because we’re doing history here, I’ll be describing the game in general as it was played in the 1990s. The modern game had not changed markedly, but there has been some tinkering here and there.

Unless another number has been agreed upon, each player starts with twenty life points. The objective is to reduce your opponent’s life points to zero before she can do the same to you. Alternatively — and less commonly — you can win through attrition, by causing her to run out of cards to play before you do.

Each player starts with her own freshly shuffled deck of cards. How many cards? That’s a little bit complicated to get into right now, involving as it does the aforementioned revolutionary aspects of the game that are external to the core rules. Suffice for now to say that the range is usually but not always between about 40 and 60, and that the number of cards is not necessarily the same for both players.

These cards fall into two broad categories. There are land cards, which provide mana, the fuel for the spells you will cast. And there are spell cards, which represent the spells themselves. There are five different types of land, from Swamps to Mountains, and each provides a different color of mana. Likewise, most of the spell cards require some quantity of a specific color of mana to play.

One of the key attributes that sets Magic apart from most card games is its asymmetry. As I already noted, each player has her own deck of cards, and these decks are not identical, what with their contents being selected by the players themselves. Some might go with a completely White deck, some with all Black. Slightly more adventurous souls might mix two colors; the really smart, brave, and/or foolhardy might dare to blend three. To use more colors than that in a deck is generally agreed to be a recipe for disaster.

In theory at least, the cards of each color are equally powerful in the aggregate, but they lend themselves to divergent play styles. White (using mana drawn from Plains) is the color of healing and protection, and its cards reflect this. Black (Swamps), on the other hand, is the color of decay, corruption, and pestilence. And so it goes with the other colors: Blue (Islands) is the color of trickery and deception, Red (Mountains) of unbridled destruction and mayhem, Green (Forests) of nature and life. The Magic colors you prefer to play with are a sort of Rorschach test, defining what sort of player you want to be if not what sort of person you already are.

On the theory that the best way to learn something is often by example, let’s begin a sample duel. I’ll play a Red and Green deck against my much cleverer wife Dorte, who is playing Black and Blue.

At the beginning of the match, Dorte and I each draw the seven cards that compose our starting hand. The game then proceeds in rounds, during each of which each player takes one turn. I’ll be the starting player, the one who takes his turn first each round. (This is not always an advantage.)

Each player gets to draw one more card at the beginning of his or her turn, and each player is then allowed to deploy a maximum of one land card during that turn. I do both, placing a Mountain on the table in front of me.

Most spell cards require you to tap your store of mana — signified by turning one or more deployed land cards sideways — in order to play them. I happen to have in my hand a Lightning Bolt, which, I can see from the symbol at the top right of the card, requires just one Red mana to cast. That’s perfect for an early strike to wake up my enemy! I tap my freshly deployed Mountain and hurl the spell, doing three points of damage to Dorte just like that, reducing her life total to seventeen. “Instant” spells like this one go directly to the graveyard — known in most other card games as the player’s discard pile — once they’ve been cast. They’re gone forever from that point on — except under special circumstances, such as a spell that lets one pull cards out of the graveyard. (One quickly learns that every rule in Magic comes with that same implied asterisk.)

On her turn, Dorte draws a card, deploys a Swamp, and does nothing else. Presumably she doesn’t have any spell cards in her hand that cost just one Black mana to cast — or any that she wants to cast right now, at any rate.

The first round is now finished, so I can untap the Mountain I’ve already put on the table. This means I will be able to use it again on my next turn.

I draw another card to start my second turn. But after doing so, I find that there’s nothing else that I’m willing and able to do with my current hand, other than to grow my Red mana stockpile a bit by deploying another Mountain. Quick turns like the ones Dorte and I have just taken are not at all unusual during the early rounds of a game. Most spells cost more than the Lightning Bolt I happened to have handy at the start, and it can take time to build up the supply of mana needed to cast them. Because land cards that have been deployed in one turn stay deployed in those that follow, the amount of mana in play escalates steadily during a game of Magic, allowing more and more powerful spell cards to be played.

Unhappily for me, Dorte doesn’t need to wait around anymore. After drawing a card and deploying a second Swamp, she has enough mana to summon a Black Knight. As a summoned minion rather than a one-shot spell, he goes out onto the table in front of her, next to her supply of land. He will soon be able to attack me, or do battle with my own minions, should I manage to summon any. Thankfully, though, he is not allowed to attack on the same turn he is summoned. And so the round ends without further ado.

I get some luck of my own on my next turn; I draw the Forest card I’ve been looking for. I immediately deploy my Forest alongside my two preexisting Mountains, giving me one Green and two Red mana to work with this turn.

I use one of each to summon my first minion (or rather minions): a group of Elven Archers. (The symbols at the top right of this card tell me that it costs one Green mana and one additional mana of any color to play.) And then, because they too aren’t allowed to attack on the turn in which I summoned them, I can do nothing else.

Dorte deploys an Island on her turn, giving her one Blue and two Black mana in her reservoir.

Then she sends her Black Knight to attack me. I’m about to respond with my Elven Archers as defenders. Take a close look at both cards. The numbers at the bottom right tell us that both attack with a power of two, but that, while the Black Knight dies only after absorbing two points of damage, my Elven Archers are more fragile, dying after taking just one point of damage. Both also have special abilities. The Black Knight is invulnerable to White enemies, but this is irrelevant in this match, since I won’t be summoning any of them. On the other hand, both the Black Knight and the Elven Archers have a “First Strike” ability. This requires a bit more unpacking.

When minions clash, they normally damage one another simultaneously. A creature with First Strike, however, damages its enemy first; if and only if the enemy is left alive by the attack does it get to inflict retaliatory damage of its own. Yet in this case, both attacker and defender have First Strike. Their special abilities cancel one another out, causing them to inflict damage on one another simultaneously as usual. The result ought to be that both are killed, going to their respective players’ graveyards. I am, in other words, prepared to sacrifice my Elven Archers in order to get Dorte’s Black Knight — a slightly more formidable pugilist on the whole — out of the game as well.

But that’s not what actually happens here — because Dorte, who hasn’t yet tapped any of her lands, does so now in order to cast a Terror spell, killing my Elven Archers outright before they can move to block her Black Knight. With his way thus cleared, the Black Knight can attack me directly, reducing my life points to eighteen. And so the round ends.

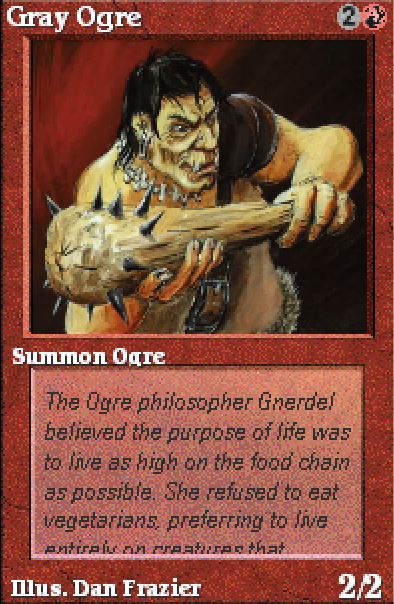

On my next turn, I deploy another Mountain, giving me a total of three Red and one Green mana. That’s more than enough to summon another minion from my hand, a Gray Ogre this time. Having done so, I end my turn.

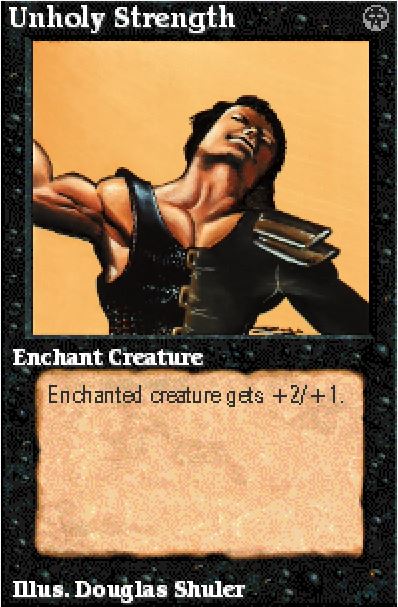

Dorte now deploys another Island, giving her a pool of two Blue and two Black mana. She uses one Black mana to cast Unholy Strength on her Black Knight, increasing his attack power to four and his hit points to three.

Then she uses one Blue mana to cast a Flight spell, giving the same Black Knight the “Flying” special ability, meaning it will be able to soar right over my (non-flying) Gray Ogre and do four points of damage to me directly. This match does not appear to be going my way.

But appearances can be deceiving. It so happened that I drew another Lightning Bolt on my last turn, and I still have one untapped Mountain left to use to cast it — not directly against Dorte this time, but rather against her augmented Black Knight. The spell’s three points of damage will be just enough to kill him, even with his newfound Unholy Strength; nor can his ability to Fly save him.

But I did tell you that Dorte is clever, right? Not wanting to lose her Black Knight permanently, she hurriedly casts Unsummon with her last remaining point of Blue mana. This allows her to take him back into her hand, to be summoned again on some future turn to fight another day — minus his buffs, which now go to her graveyard without him.

The outcome of the last round has been mixed, but by no means ruinously so for me. I’ve been able to avoid taking any more damage, have forced Dorte’s only minion out of play for the moment, and now have a minion of my own poised to take the offensive next round. I’ll chalk the round up as more successful than not, even as I worry about what Dorte might still have up her sleeve — or rather in her hand — for dealing with my Gray Ogre.

And so it goes. A game of Magic is a cat-and-mouse one of move and countermove, strike and counterstrike, feint and counter-feint.

Although the explanation above is highly simplified, the core gameplay loop of Magic really is fairly easy to teach and to learn. The game’s ability to obsess its players over the long term derives not from its core rules but from the cards themselves. Through them, a simple game becomes devilishly complex — albeit complex in a different sense from, say, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, with its hundreds of pages of closely typed rules. In Magic, by contrast, all of the rules beyond the most basic are literally printed right there on the cards. The rules thus rewrite themselves every time somebody brings a new card to a session. This was unprecedented enough in the early 1990s to be called revolutionary — and not only in the sense of pure game design, but in a cultural and commercial sense as well. For Magic, you see, was envisioned from the start as a collectible card game, the world’s first.

This meant that there wouldn’t be a single monolithic Magic game to buy, containing everything you needed to play. Each player would instead assemble his own unique deck of cards by buying one or more card packs from Wizards of the Coast and/or by trading cards with his friends. All of the card packs produced by Wizards would be randomized. No one — not Wizards, not the store that sold them, definitely not you the buyer — could know for sure what cards any given pack contained. You would have to pay your money and take your chances on whatever pack seemed to be calling to you from its shelf in the store on that day.

The concept was utterly original, arguably more so than anything that had been seen in tabletop gaming since Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson had unleashed their “single-unit wargame” Dungeons & Dragons. But because of its unprecedented nature, Magic took a long, long time to turn into a reality. For, whatever its other merits, Magic did not live up to Peter Adkison’s request for a card game that would be simple and cheap to turn into a finished product.

First there was the work of making up hundreds of cards and their abilities, then of testing them against one another over and over to find out which ones were too powerful, which ones weren’t powerful enough, and which ones had been a bad idea from the get-go. Richard Garfield’s expertise in combinatorics was a godsend here, as was that of the other mathematicians who surrounded him at the University of Pennsylvania. “Richard would grab people for games all the time,” remembers one of those colleagues, the fellow who had the office across the hall from his. “If you said yes once, you were in the loop.” Magic became a way of life at the math department, threatening to derail graduations and theses. The University of Pennsylvania was the first educational institution to be so afflicted; it would not be the last.

The process of hewing a real game out of Garfield’s stroke of genius took so long that Peter Adkison came close to writing the whole project off, notwithstanding his bellow of enthusiasm in that Seattle parking lot after he had first been told of it. While he waited to see if Garfield would come through, he tried to bootstrap Wizards of the Coast by making supplements for established RPG lines. But his very first effort in this direction, a source book dealing with deities and their religions, nearly brought an end to the whole operation; the included notes on how to use the material with The Palladium Fantasy Role-Playing Game got him sued. He wound up having to scrap the source book and pay Palladium Books a settlement he really couldn’t afford. All he could do was chalk it up as a lesson learned. It wasn’t worth it to piggyback on anyone else’s intellectual property, he decided. Better for Wizards of the Coast to build its own inviolate empire with Magic.

Early in 1993 — fully eighteen months after that eureka moment in Seattle — Garfield finally delivered an initial slate of 300 different cards that he judged to be adequately tested and balanced. Now Adkison’s work began. He considered it essential that Magic look as good as it played; a part of the appeal of collecting the cards should be purely aesthetic. He farmed the illustrations out to a small army of freelance artists, most of them students at Seattle’s Cornish College of the Arts, who agreed to work for royalties and stock in lieu of the up-front fees that Adkison couldn’t afford to pay them; he also offered them the unusual bonus of seeing their names featured right there on the fronts of the cards themselves.

You would begin your journey into the realms of Magic by buying a 60-card “Starter Deck,” at a price of $7.95. After that, you could add to your deck’s possibilities by buying 15-card “Booster Packs,” which would sell for $2.45 each. Working out the top-secret algorithms that would dictate the card packs’ contents was an enormously complicated exercise in combinatorics, one that put even Garfield’s skills to the test. Starter Decks, for example, had to be reasonably playable all by themselves, with a balance between types of land and spells that required that color of mana. To introduce a modicum of balance into the Magic economy as a whole, Garfield classified each card as common, uncommon, or rare, with their proportions in a print run and in each individual pack within that run to be dictated accordingly. Adkison awarded the contract to print the cards to a firm in far-off Belgium, the only one he could find that was willing and able to piece together so many bespoke packages.

He planned to introduce Magic to the world in August of 1993 at Gen Con, the highlight of the hobbyist-gaming calendar. It very nearly didn’t happen. Having paid for a booth at the tabletop-gaming Mecca, he was flustered when the cards he intended to show and sell there failed to arrive in time from Belgium. He spent the first and most of the second day of the four-day show standing in front of the empty booth, telling nonplussed gamers about the revolutionary game he would like to be showing them but for a logistical snafu. Needless to say, it was not a good look.

At long last, on the afternoon of the second day, the truck he had been waiting for arrived from the East Coast. Adkison and his people ripped open the shipping boxes right there on the show floor and began stacking the card packs around them. The show attendees still looked skeptical, still didn’t quite seem to understand the concept: “What? Each player needs his own deck?” But eventually a few took the plunge on a Starter Pack, then a few more. Then a lot of people did so, even as the earliest adopters started coming back to pick up Booster Packs. And then the second wave of Starter Pack buyers returned to buy more Booster Packs, as the future of Magic played out in microcosm right there in the hallways, hotel rooms, cafeterias, and gaming halls of Gen Con. Adkison sold $25,000 worth of Magic that weekend. On Monday morning, he walked into Boeing and tendered his resignation.

Dragon magazine, the journal of record of hobbyist gaming on the tabletop, had a reporter on the scene at the show. Allen Varney’s article is prescient in many ways, although even he couldn’t possibly know just how big Magic would become.

Through the Gen Con Game Fair, people clustered three deep around the Wizards of the Coast table, craning to see the ongoing demonstrations of this game. Everywhere I went I saw someone playing it. In discussing it, some players showed reserved admiration, others enthusiasm, but body language told more than words. Everyone hunched forward intently, the way you do in deep discussions of politics or religion. Onlookers and devoted fans alike felt compelled to grapple with the idea of this game. It achieved more than just a commercial hit; it redefined gamers’ perspectives on their hobby.

The Magic: The Gathering card game, the trailblazer in what may become an entire industry category, combines card-game rules with trading-card collectability…

The Magic game requires a medium to large league of players to bring out its magic. Fortunately, its low entry price, simplicity, and quick play make this easier to achieve. It makes an ideal choice for conventions or lunch boxes. Its drawbacks seem minor beside its groundbreaking achievement.

Things happened quickly after Gen Con — so quickly that Dragon saw the need to append a hasty postscript to Varney’s original review in the very same issue in which it first appeared. Already at this point Magic could only be described as a “phenomenon.”

As I write this postscript, about six weeks after the game’s release, Magic has attracted legions of instant fanatics. The decks have sold out everywhere. Retailers frantically await follow-up shipments of millions of cards. I know lots of gamers who play the game long into the night, and weigh trade offers the way home buyers study mortgage contracts. I wonder what these junkies did before the game appeared; probably the junkies wonder too.

Yes, if you must know, I have become a junkie myself. The review above fails to highlight the game’s addictive quality, which clicks in when you appreciate the diverse strategies you can pursue in tailoring your deck or decks; you may create decks for different situations, like a golfer choosing irons. These decks display fascinating contrasts keyed to the colors and creatures they use, and to the players who use them…

Owning a large number of different cards seems to confer an odd, unspoken status. So does ownership of a particular rare card that no one else owns. Because every deck contains rare cards, this means a neophyte can buy one Magic deck and acquire instant stature among these long-time players: “Wow, he’s got a Lord of the Pit!” This seems to me something new in the gaming subculture, another sign of the game’s pioneering nature…

The allure of the rarest cards was partially down to the collector instinct alone; while those who called Magic the nerdy kid’s version of baseball cards overlooked much of the full picture, they weren’t entirely wrong either. In addition, though, uncommon and especially rare cards tended to be, when played properly, more powerful than their more plebeian comrades that might have been acquired inside the same cellophane wrapping.

It’s extraordinary to think that all of this was happening already just six weeks after Magic‘s debut. No other game in the hobby market had ever exploded out of the gates like this. Peter Adkison had used every dime he could scrape together from family, friends, bankers, and personal savings to fund an initial print run of 2.6 million cards, which he had thought should get him through the next year if the game took off like he hoped it would. It sold out within a week, leaving him scrambling to put together a second run of 7.3 million cards. That one too sold out in pre-orders before it had even arrived Stateside from Belgium. Not only were gamers demanding more cards in general, but also more types of cards. Adkison set Richard Garfield, who had just received a PhD after his name that he would never need to use now, to dreaming up and play-testing new cards.

Why was Magic such a hit? The answer is not that hard to grasp in the broad strokes, but there were some troubling ethical dilemmas lurking behind its success. While there’s no doubt that Magic was a genuinely great, compelling game, there’s also little doubt that it ruthlessly exploited the insecurities of its primary fan base: teenage males of a, shall we say, mathematical rather than athletic disposition. As anyone who has ever seen a computer-coding contest or a DOOM deathmatch can tell you, these kids aren’t a jot less competitive than the jocks that they mock and are mocked by; they’ve just transferred their competitive instinct to a different arena. It does seem to me that hyper-competitiveness is rooted in personal insecurity. And who is as insecure as a teenage boy of any high-school clique, other than perchance a teenage girl?

In practice, then, the story might go something like this:

A kid keeps hearing about this neat new game called Magic, and finally goes out and buys himself a Starter Pack. Now, he needs people to play with. So he shows his cards to some of his buddies, and convinces them to go out and buy Starter Packs of their own. They all start to play together — in fact, they start to play every chance they get, because the game turns out to be really, really fun. Taking less than twenty minutes to play a match as it does, it’s perfect for squeezing into school lunch breaks and the like.

So far, so good. But one kid in the group is having a bit more trouble than the others coming to terms with the game. He loses more than any of his friends, perhaps even becomes known as the pushover of the group, to be teased accordingly. Being a teenage boy, he likes that not at all. He’s been seeing these Booster Packs at the local gaming store. Could one of those give him a leg up? He decides to take a chance. And he’s rewarded for his initiative: he gets one or two powerful new cards, and suddenly he isn’t losing so much anymore.

Of course, the other kids in the group are hardly unaware of the source of their friend’s novel formidability. They grumble about how pathetic it is to go out and buy your way to victory. Eventually, though, one of them breaks down and buys a Booster Pack of his own. And so the arms race begins. Soon the boys are spending allowances, lawn-cutting and paper-route earnings, paychecks from Burger King on more and more Booster Packs. They tear each new one open, flinging the common and even uncommon cards into a big pile of the undesirable in the center of their bedroom, which sits there like vanities awaiting the bonfire while their owners look desperately for that Time Walk or Ancestral Recall that will let them dominate. The blessed day comes they do find what they’ve been looking for — but then they find that it’s still not enough, because the other boys have also upgraded their decks. And so the vicious cycle continues, fueled by the more cards that Wizards of the Coast is constantly inventing and churning out as quickly as a body ludic of adolescent addicts can absorb them into its bloodstream.

I hasten to add that it never had to go down this way. Theoretically speaking, a group of friends could decide to get into Magic, buy a Starter Pack or two each, and agree that that was as far as they would go. Such disciplined souls would be rewarded with an entertaining, deceptively intricate little card game that was well worth the relatively paltry sum they’d paid for it. But still, the chance that someone would give in to the shrink-wrapped temptations beckoning from the shelves of the local gaming store was always there. And after they did so, all bets were off.

I must acknowledge here as well that the motivation to buy more and more Booster Packs wasn’t always or even usually purely egotistical. Deck-building became a fascinating art and science in itself. Among advanced players, Magic duels tended to be won or lost before they even began, being determined by the mix of cards each player had in his deck. Remember that the number and types of cards in a deck were entirely up to that deck’s owner. Refining a deck into a precision-guided killing machine was an education in itself in probability and statistics. For example, how many land versus spell cards were optimal? If you drew too few land cards, you might find yourself unable to do much of anything while your opponent pounded on you; too many land cards, on the other hand, were clutter in your hand that just as effectively prevented you from getting summoned minions and other spells into play. And how many cards should you have in total, for that matter? Inexperienced players with more money than sense tended to assemble motley monstrosities of decks with 80 cards or more, only to learn that their probability of getting the right combinations of cards into their hand with such a deck was far too low. Lean and mean decks that did just a few things extremely well were almost always better than a random smorgasbord of even the rarest, most powerful cards.

All of which is to say that, at the most advanced level, Magic came to revolve around specific, devious combinations of cards that multiplied one another’s strengths in unexpected ways. Allow me to cite a simple example, laughably so by the standards of skilled players.

Consider the case of the Lifetap. This card is deadly against an opponent who relies heavily on Green mana, because it lets you gain one point of life every single time he taps one of his Forests for the mana he needs. It puts him in a place where literally everything he tries to do to kill you only makes you stronger. Yet it’s useless against an opponent who isn’t using Green mana, nothing but clutter in your deck. Or is it?

If you can put it into a play alongside a Magic Hack, it becomes an all-purpose game changer. For Magic Hack, you see, will let you change the word “Forest” on the Lifetap card to whatever land your opponent happens to be relying on most of all.

Of course, you have to balance the number of Lifetaps and Magic Hacks in your deck to give yourself a reasonable chance of getting them into play in combination, without having so many that you don’t see enough of the other cards you will need to win. And so begins the endless process of tinkering and honing that is the fate and the passion of the serious student of Magic…

By way of summation, then, Magic: The Gathering was simultaneously a great game in its own right and a downright dangerous pastime for the right (or wrong?) kind of mind. It could deliver an enormous amount of satisfying fun, or it could eat up all of one’s money and free time, distracting from other, less zero-sum forms of social interaction and trapping its victims into a wallet-emptying spiral of addiction. Even teenage players could recognize its dangers, for all that they often couldn’t see their way clear of them; they took to calling those tempting Booster Packs “Crack in a Pack.” In Generation Decks, his thoughtful book-length history of Magic, Titus Chalk describes the unhealthily cloistered air of the shop backrooms in which Magic thrived.

These shops are turf. The tangible space a community has carved out for itself, and which it is loath to surrender again. Here there is safety in numbers. Reassurance in peers who look, act, and speak the same. And a comfort to looking inwards rather than out through cluttered windows. Hiding in the shadows, these places preserve the community’s cosiness, without holding it up to scrutiny or opening it up to others whose different values might enrich it. The physical environment is a symptom of its inhabitants’ insecurities. In gloomy backrooms, Magic cloaks itself in stigma.

How do you encourage a community to look outwards when it is so accustomed to lurking in the margins?

Richard Garfield insists that exploiting his young players was never on his mind when he was designing Magic, and we have no reason to disbelieve him. Indeed, his original vision for the Magic economy was actually quite different from what the reality became. He imagined that Magic would become primarily a trading game, in which a pool of cards that grew only slowly if at all would circulate busily among a community of players. Barry Reich, a fellow graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania who helped Garfield refine the game before its release, says that they imagined back then that “extravagant people might buy two [Starter] Decks and [thereafter] a Booster Pack or two a year.”

The game’s most notorious early rule stemmed directly from this vision of a semi-closed economy with only limited external stimulus in the form of new cards. That rule was the “ante.” It stipulated that, before beginning a game, each player would randomly draw one card from his deck and set it aside; the winner of the match would then get to take the loser’s ante card home with him. If you squint just right, you can sort of see this rule through Garfield’s eyes. The ante would get and keep cards moving through the Magic community.

Still, its problematic aspects ought to have been obvious even to an innocent like him. How much fun could it be for a new player, trying Magic for the first time, to pay for the learning experience by losing card after card? As if that wasn’t argument enough against it, the rule effectively turned Magic into a Wizards of the Coast-sanctioned form of gambling, one that was literally illegal according to the laws of many American states; you were, after all, playing a game with a strong element of chance for objects of real monetary value. The fact that the gamblers in this case were mostly underage only made the optics that much worse. Small wonder that, within a few years of Magic‘s release, the ante would be quietly retired and scrubbed as much as possible from the game’s history. Its only saving grace while it existed was that it was officially described as “optional.”

In the spirit that every rule in Magic comes complete with a card-provided asterisk, some early cards played with the ante mechanic. This one, which lets you draw seven new cards into your hand for the price of just one Black mana, is very potent. But you also pay for that potency by risking two cards instead of one on the outcome of the match.

Wizards of the Coast grew from a handful of people working out of Peter Adkison’s basement in 1993 to 50 employees in 1994, then to 250 in 1995. It even started publishing Magic novels — a rather cheeky move, given how thin the fiction and “universe” of the card game was, drawing indiscriminately on everything from the myths of King Arthur to the mythos of H.P. Lovecraft. (Lots of Magic addicts bought the books mainly for the coupons to be found at the back of them, which could be mailed in to receive a card that was otherwise unavailable.) The company was drowning in money, with profit margins on the ubiquitous little cards that the makers of traditional tabletop games could only dream of.

It soon became all too clear that, although Magic was certainly drawing some new folks into the circle of tabletop gamers, most of its success was coming at the expense of every other company in that market — not least the 800-ton mothership, TSR of Dungeons & Dragons fame, the host of the Gen Con convention where Magic had gotten its start. The marketplace calculus proved to be as relentlessly zero-sum as a Magic duel: the new game’s young fans had only a limited amount of funds to splash around, so that every dollar they spent on Magic was a dollar they couldn’t spend on Dungeons & Dragons or the like. Anyone from the industry’s old guard who might have been sleeping at the switch was fully alerted to the magnitude of the crisis at the 1994 Gen Con, which seemed to be about little else than this little card game that was now celebrating its first birthday. “The joke of the convention was that if there was any horizontal space, Magic players were playing on it,” says Mark Rosewater, then a writer for The Duelist, Wizards of the Coast’s new in-house magazine. “As you walked through the convention halls, you could see Magic players camped out all over the floor.” The first annual Magic World Championship was held at the convention: 500 players dueling for the title of best in the world, overshadowing everything else that went on there. Soon there would be a Magic Pro Tour to compete with the World Series of Poker.

The growing chorus of grumbles about Magic that could be detected underneath all the hysteria was the very definition of sour grapes, on the part of gamers and companies who saw a silly card game stealing away from them a hobby that they loved. But be that as it may, there were valid points to be detected amidst the chorus. In Dungeons & Dragons, you lived through the triumphs and tragedies of the dice together with your friends; in Magic, you did your level best to beat them. Something about the game seemed to bring out the worst in many of its players. The vibes in the room at Magic tournaments weren’t always the most pleasant.

Then, too, Dungeons & Dragons was a creative endeavor in a way that Magic wasn’t. Although it was easy to forget amidst the torrent of source books and adventure modules unleashed by the TSR of the 1990s, Dungeons & Dragons had once taken it as a given that you would make up your own worlds and adventures from whole cloth, and that ideal was still lodged somewhere deep in even in the current game’s DNA; in principle, you could still have a marvelous time exploring realms of the imagination with your friends after buying no more than the core trio of rule books. Magic, on the other hand, belonged to Wizards of the Coast, not to its players; the latter could only play with the content their ludic overlords deigned to give them, content of which they were forced to keep buying more and more by peer pressure and the need to stay competitive — which were largely one and the same, of course.

Yet such philosophical objections didn’t stop the other gaming companies from doing what they felt they had to in order to survive: making Magic-style collectible card games of their own. TSR was actually one of the first to do so, rushing out a product called Spellfire, reportedly designed over a weekend and then slapped together using recycled Dungeons & Dragons art. When it didn’t set the world on fire, they tried again with Dragon Dice, which at least scored some points for innovation by replacing cards with piles and piles of bespoke dice. Many, many others joined the fray as well. There were collectible card games based on Mortal Kombat, on The Lord of the Rings, on Babylon 5, on Star Wars and Star Trek, even on Monty Python, to say nothing of the dozens of also-rans who tried to make a go of it without the benefit of a license. Some did okay for a while, but none came anywhere close to Magic numbers. This applied even to Netrunner and The BattleTech Collectible Card Game, both designed by Richard Garfield himself for Wizards of the Coast, both commercial disappointments.

And then too there was a Magic computer game, to which one of the most famous designers in that industry lent his considerable talents. It will be our subject next time…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Designers & Dragons: The 80s by Sheldon Appelcline, Slaying the Dragon: A Secret History of Dungeons & Dragons by Ben Riggs, and Generation Decks: The Unofficial History of Gaming Phenomenon Magic: The Gathering by Titus Chalk, Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and the People Who Play It by David M. Ewalt, and The Fantasy Roleplaying Bible, second edition, by Sean Patick Fannon. Plus the Dragon of January 1994 and the January 2018 issue of Seattle Met. Online sources include interviews with Richard Garfield on Board Game Geek, Vice, Star City Games, Magic F2F, and the official Magic YouTube channel.