On December 14, 1990, Scott Miller of Apogee Software uploaded the free first installment of his company’s latest episodic game. He knew as he did so that this release would be, if you’ll pardon the pun, a game changer for Apogee. To signal that this was truly a next-generation Apogee game, he doubled his standard paid-episode asking price from $7.50 to $15.

Rather than relying on the character graphics or blocky visual abstractions of Apogee’s previous games, Commander Keen 1: Marooned on Mars was an animated feast of bouncy color. Rather than looking like a typical boxed game of five to ten years earlier, it looked quite literally like nothing that had ever been seen on an MS-DOS-based computer before. In terms of presentation at least, it was nothing less than computer gaming’s answer to Super Mario Bros., the iconic franchise that had done so much to help Nintendo sell more than 30 million of their videogame consoles in the United States alone.

Yet even Miller, who has been so often and justly lauded for his vision in recognizing that many computer owners were craving something markedly different from what the big game publishers were offering them, could hardly have conceived of the full historical importance of this particular moment. For it introduced to the world a small group of scruffy misfits with bad attitudes and some serious technical chops, who were living and working together at the time in a rundown riverfront house in Shreveport, Louisiana. Within a few months, they would begin to call themselves id Software, and under that name they would remake the face of mainstream gaming during the 1990s.

I must admit that I find it a little strange to be writing about humble Shreveport for the second time in the course of two articles. It’s certainly not the first place one would look for a band of technological revolutionaries. The perpetually struggling city of 200,000 people has long been a microcosm of the problems dogging the whole of Louisiana, one of the poorest states in the nation. It’s a raggedly anonymous place of run-down strip malls and falling-down houses, with all of the crime and poverty of New Orleans but none of that city’s rich cultural stew to serve as compensation.

Life in Shreveport has always been defined by the Red River which flows through town. As its name would imply, the city was founded to serve as a port in the time before the nation’s rivers were superseded by its railroads and highways. When that time ended, Shreveport had to find other uses for its river: thanks to a quirk of Louisiana law that makes casinos legal on waterways but not on dry land, residents of northeastern Texas and southern Arkansas have long known it primarily as the most convenient place to go for legal gambling. The shabbily-dressed interstate gamblers who climb out of the casino-funded buses every day are anything but the high rollers of Vegas lore. They’re just ordinary working-class folks who really, really should find something more healthy to do with their time and money than sitting behind a one-armed bandit in a riverboat casino, dropping token after token into the slot and staring with glazed eyes at the wheels as they spin around and around. This image rather symbolizes the social and economic condition of Shreveport in general.

By 1989, Al Vekovius of Shreveport’s Softdisk Publications was starting to fear that the same image might stand in for the state of his business. After expanding so dramatically for much of the decade, Softdisk was now struggling just to hold onto its current base of subscribers, much less to grow their numbers. The original Softdisk and Loadstar, their two earliest disk magazines, catered to aged 8-bit computers that were now at the end of their run, while Big Blue Disk and Diskworld, for MS-DOS computers and the Apple Macintosh respectively, were failing to take up all of their slack. Everything seemed to be turning against Softdisk. In the summer of 1989, IBM, whose longstanding corporate nickname of “Big Blue” had been the source of the name Big Blue Disk, threatened a lawsuit if Softdisk continued to market a disk magazine under that name. Knowing better than to defy a company a thousand times their size, Softdisk felt compelled to rename Big Blue Disk to the less catchy On Disk Monthly.

While the loss of hard-won brand recognition always hurts, Softdisk’s real problems were much bigger and more potentially intractable than that of one corporate behemoth with an overgrown legal department. The fact was, the relationship which people had with the newer computers Softdisk was now catering to tended to be different from the one they had enjoyed with their friendly little Apple II or Commodore 64. Being a computer user in the era of Microsoft’s ascendancy was no longer a hobby for most of them, much less a lifestyle. People had less of a craving for the ramshackle but easily hackable utilities and coding samples which Softdisk’s magazines had traditionally published. People were no longer interested in rolling up their sleeves to work with software in order to make it work for them; they demanded more polished programs that Just Worked right off the disk. But this was a hard field for Softdisk to compete on. Programmers with really good software had little motivation to license their stuff to a disk magazine for a relative pittance when they could instead be talking to a boxed-software publisher or testing the exploding shareware market.

With high-quality submissions from outside drying up just as he needed them most, Vekovius hired more and more internal staff to create the software for On Disk. Yet even here he ran up against many of the same barriers. The programmers whom he could find locally or convince to move to a place like Shreveport at the salaries which Softdisk could afford to pay were generally not the first ones he might have chosen in an ideal world. For all that some of them would prove themselves to be unexpectedly brilliant, as we’ll see shortly, virtually every one of them had some flaw or collection thereof that prevented him from finding gainful employment elsewhere. And the demand that they churn out multiple programs every month in order to fill up the latest issue was, to say the least, rather inimical to the production of quality software. Vekovius was spinning his wheels in his little programming sweatshop with all the energy of those Shreveport riverboat gamblers, but it wasn’t at all clear that it was getting him any further than it was getting them.

Thus he was receptive on the day in early 1990 when one of his most productive if headstrong programmers, a strapping young metalhead named John Romero, suggested that Softdisk start a new MS-DOS disk magazine, dedicated solely to games — the one place where, what with Apogee’s success being still in its early stages, shareware had not yet clearly cut into Softdisk’s business model. After some back-and-forth, the two agreed to a bi-monthly publication known as Gamer’s Edge, featuring at least one — preferably two — original games in each issue. To make it happen, Romero would be allowed to gather together a few others who were willing to work a staggering number of hours cranking out games at an insane pace with no resources beyond themselves for very little money at all. Who could possibly refuse an offer like that?

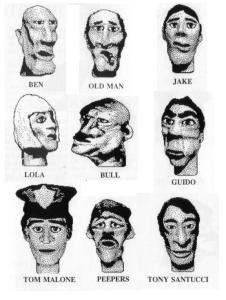

The id boys: John Carmack, Kevin Cloud, Adrian Carmack, John Romero, Tom Hall, and Jay Wilbur.

The team that eventually coalesced around Romero included programmer Tom Hall, artist Adrian Carmack, and business manager and token adult-in-the-room Jay Wilbur. But their secret weapon, lured by Wilbur to Shreveport from Kansas City, Missouri, was a phenomenal young programmer named John Carmack. (In a proof that anyone who says things like “I don’t believe in coincidences” is full of it, John is actually unrelated to Adrian Carmack despite having the same not-hugely-common last name.) John Carmack would prove himself to be such a brilliant programmer that Romero and Hall, no slouches themselves in that department by most people’s standards, would learn to leave the heavy lifting to his genius, coding themselves only the less important parts of the games along with the utilities that they used to build them — and they would also design the games, for Carmack was in reality vastly more interested in the mathematical abstraction of code as an end unto itself than the games it enabled.

But all of these young men, whom I’ll call the id boys from here on out just because the name suited them so well even before they started id Software, will be more or less important to our story. So, we should briefly meet each of them.

Jay Wilbur was by far the most approachable, least intimidating member of the group. Having already reached the wise old age of 30, he brought with him a more varied set of life experiences that left him willing and able to talk to more varied sorts of people. Indeed, Wilbur’s schmoozing skills were rather legendary. While attending university in his home state of Rhode Island, he’d run the bar at his local TGI Friday’s, where his ability to mix drinks with acrobatic “flair” made him one of those selected to teach Tom Cruise the tricks of the trade for the movie Cocktail. But his love for the Apple II he’d purchased with an insurance settlement following a motorcycle accident finally overcame his love for the nightlife, and he accepted a job for a Rhode Island-based disk magazine called UpTime. When that company was bought out by Softdisk in 1988, he wound up in Shreveport, working as an editor there. The people skills he’d picked up tending bar would never desert him; certainly his new charges at Gamer’s Edge had sore need of them, for they were an abrasive collection of characters even by hacker standards.

These others loved heavy metal and action movies, and aimed a well-sharpened lance of contempt at anything outside their narrow range of cultural and technical interests. Their laser focus on their small collection of obsessions would prove one of their greatest strengths, if perhaps problematic for gaming writ large in the long run, in the way that it diminished the scope of what games could do and be.

Yet even this band of four, the ones who actually made the games for Gamer’s Edge under Wilbur’s benevolent stewardship, was not a monolith. Once one begins to look at them as individuals, the shades of difference quickly emerge.

Like Wilbur, the 25-year-old Wisconsinite Tom Hall was a middle-class kid with a university degree, but he had none of his friend and colleague’s casual bonhomie with the masses. He lived in a fantasy world drawn from the Star Wars movies, the first of which he’d seen in theaters 33 times, and the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy novels, which he could all but recite from heart. At Softdisk, to which he’d come after deciding that he couldn’t stand the idea of a job in corporate data processing, he ran around talking in a cutsey made-up alien language: “Bleh! Bleh! Bleh!” He was the kind of guy you either found hilarious or were irritated out of your mind by.

The 21-year-old Adrian Carmack also lived in a world of fantasy, but his fantasies had a darker hue. Growing up right there in Shreveport, he had spent many hours at arcades, attracted not so much by the games themselves as by the lurid art on their cabinets. He worked for a time as an aide at a hospital, then went home to sketch gunshot wounds, severed limbs, and festering bedsores with meticulous accuracy. Instead of a cat or a dog, he chose a scorpion as a pet. He’d come to Softdisk on a university internship after telling his advisor he wanted to work in “fine art” someday.

Still, and with all due respect to these others, the id boys would come to be defined most of all by their two Johns. The 22-year-old John Romero was pure id, a kettle of addled energy that was perpetually spilling over, sending F-bombs spewing every which way; David Kushner, author of the seminal history Masters of Doom, memorably describes him as “a human exclamation point.” The not-quite-20-year-old John Carmack was as quiet and affectless as Romero was raucous, often disturbingly so; Sandy Petersen, a game designer who will come to work with him later in our story, remembers musing to himself after first meeting Carmack that “he doesn’t know anything about how humans think or feel.”

Yet for all their surface differences, the two Johns had much in common. Both were brought up in broken homes: Romero was physically abused by his stepfather while growing up in the Sacramento area, while Carmack suffered under the corporeal and psychological rigors of a strict private Catholic school in Kansas. Both rebelled by committing petty crimes among other things; Carmack was sentenced to a year in a boys’ detention center at age 14 after breaking into his school using a homemade bomb. (The case notes of the police officer who interviewed him echo the later impressions of Sandy Petersen: “Boy behaves like a walking brain… no empathy for other human beings.”)

Both found escape from their circumstances through digital means: first via videogames at the local arcades, then via the Apple II computers they acquired by hook or by crook. (Carmack’s first computer was a stolen one, bought off the proverbial back of a truck.) They soon taught themselves to program well enough to put professionals to shame.

Romero got his games published regularly by print magazines as type-in listings, then parlayed that into a job with the disk magazine UpTime, where he became friends with Jay Wilbur. After that, he got a job as a game porter for Origin Systems of Ultima fame. Meanwhile Wilbur moved on to Softdisk while Romero was at Origin. When Romero found himself bored by the life of a porter, he came to Shreveport as well to join his friend.

John Carmack, being more than two years younger than Romero and much more socially challenged, brought a shorter résumé with him to Shreveport when he became the only id boy to be hired specifically to work on Gamer’s Edge rather than being transferred there from another part of Softdisk. He had mostly sold his games for $1000 apiece to a little mom-and-pop company near his home called Nite Owl Productions, who had made them a sideline to their main business of supplying replacement batteries for Apple II motherboards. But he had also sold one or two games to Jay Wilbur at Softdisk. Finding these to be very impressive, the id boys asked Wilbur to deploy his considerable charm to recruit the new kid for Gamer’s Edge. After a concerted effort, he succeeded.

Gamer’s Edge was far more than just a new job or a workplace transfer for the young men involved. It was a calling; they spent virtually all day every day in one another’s company. Pooling all of their meager salaries, Wilbur rented them a rambling old four-bedroom house on the Red River, complete with a Jacuzzi and a swimming pool and a boat deck which he soon complemented with a battered motorboat. It was an Animal House lifestyle of barbecuing, water skiing, and beer drinking in between marathon hacking sessions, fueled by pizza and soda. Wilbur — in many ways the unsung hero of this story — acted as their doting den mother, keeping the lights on, the basement beer keg filled, the refrigerator stocked with soda and junk food, and the pizza deliveries coming at all hours of the day and night.

Inside the riverfront house in Shreveport. John Carmack sits near center frame, while John Romero is to his left, mostly hidden behind a pillar.

For the first issue of Gamer’s Edge, the two Johns agreed to each port one of their old Apple II games to MS-DOS. Romero chose a platformer called Dangerous Dave, while Carmack chose a top-down action-adventure called Catacomb. They raced one another to see who could finish first; it was after losing rather definitively that Romero realized he couldn’t hope to compete with Carmack as a pure programmer, and should probably leave the most complicated, math-intensive aspects of coding to his friend while he concentrated on all the other things that make a good game. For the second issue, the two Johns pooled their talents with that of the others to make a completely original shoot-em-up called Slordax: The Unknown Enemy. So far, so good.

And then came John Carmack’s first great technical miracle — the first of many that would be continually upending everything the id boys were working on in the best possible way. To fully explain this first miracle, a bit of background is necessary.

Although they were making games for MS-DOS, the id boys had little use for the high-concept themes of most other games that were being made for that platform in 1990; neither complicated simulations nor elaborate interactive movies did anything for them. They preferred games that were simple and visceral, fast-paced and above all action-packed. Tellingly, most of the games they preferred to play these days lived on the Nintendo Entertainment System rather than a personal computer.

Much of the difference between the two platforms’ design aesthetics was cultural, but there was also more to it than that. As I’ve often taken pains to point out in these articles, the nature of games on any given platform is always strongly guided by that platform’s technical strengths and weaknesses.

When first looking at the NES and an MS-DOS personal computer of 1990 vintage, one might assume that the latter so thoroughly outclasses the former as to make further comparison pointless. The NES was built around a version of the MOS 6502, an 8-bit CPU dating back to the 1970s, running at a clock speed of less than 2 MHz; a state-of-the-art PC had a 32-bit CPU running at 25 MHz or more. The NES had just 2 K of writable general-purpose memory; the PC might have 4 MB or more, plus a big hard drive. The NES could display up to 25 colors from a palette of 48, at a resolution of 256 X 240; a PC with a VGA graphics card could display up to 256 colors from a palette of over 262,000, at a resolution of 320 X 200. Surely the PC could effortlessly do anything the NES could do. Right?

Well, no, actually. The VGA graphics standard for PCs had been created by IBM in 1987 with an eye to presenting crisp general-purpose displays rather than games. In the hands of a talented team of pixel artists, it could present mouth-watering static illustrations, as adventure-game studios like Sierra, LucasArts, and Legend were proving. But it included absolutely no aids for fast animation, no form of graphical acceleration whatsoever. It just gave the programmer a big chunk of memory to work with, whose bytes represented the pixels on the screen. When she wanted to change said pixels, she had to sling all those bytes around by main force, using nothing but the brute power of the CPU. All animation on a PC was essentially page-flipping animation, requiring the CPU to redraw every pixel of every frame in memory, at the 20 or 30 frames per second that were necessary to create an impression of relatively fluid motion, and all while also finding cycles for all of the other aspects of the game.

The graphics system of the NES, on the other hand, had been designed for the sole purpose of presenting videogames — and in electrical engineering, specialization almost always breeds efficiency. Rather than storing the contents of the screen in memory as a linear array of pixels, it operated on the level of tiles, each of which was 8 X 8 or 8 X 16 pixels in size. After defining the look of each of a set of tiles, the programmer could mix and match them on the screen as she wished, at a fairly blazing speed thanks to the console’s custom display circuitry; this enabled the smooth scrolling of the Super Mario Bros. games among many others. She also had up to 64 sprites to work with; these were little 8 X 8 or 8 X 16 images that were overlaid on the tiled background by the display hardware, and could be moved about almost instantaneously, just by changing a couple of numbers in a couple of registers. They were, in other words, perfect for showing Super Mario bouncing around on a scrolling background, at almost no cost in CPU cycles. Freed from the heavy lifting of managing the display, the little 6502 could concentrate almost entirely on the game logic.

The conventional wisdom of 1990 held that the PC, despite all its advantages in raw horsepower, simply couldn’t do a game like Super Mario Bros. The problem rankled John Carmack and his friends particularly, given how much more in tune their design aesthetic was with the NES than with the current crop of computer games. And so Carmack turned the full force of his giant brain on the problem, and soon devised a solution.

As so often happens in programming, said solution turned out to be deceptively simple. It hinged on the fact that one could define a virtual screen in memory that was wider and/or taller than the physical screen. In this case, Carmack made his virtual screen just eight pixels wider than the physical screen. This meant that he could scroll the background with silky smoothness through eight “frames” by changing just two registers on the computer — the ones telling the display hardware where the top left corner of the screen started in the computer’s memory. And this in turn meant that he only had to draw the display anew from scratch every eighth frame, which was a manageable task. Once he had the scrolling background working, he added some highly optimized code to draw and erase in software alone bouncing sprites to represent his pseudo-Mario and enemies. And that was that. His technique didn’t even demand VGA graphics; it could present a dead ringer for the NES Super Mario Bros. 3 — the latest installment in the franchise — using the older MS-DOS graphics standard of EGA.

I should note at this point that the scrolling technique which John Carmack “invented” was by no means entirely new in the abstract; programmers on computers like the Commodore 64 and Commodore Amiga had in fact been using it for years. (I point readers to my article on the techniques used by the Commodore 64 sports games of Epyx and particularly to my book-length study of the Amiga for more detailed explanations of it than the one I’ve provided here.) A big part of the reason that no one had ever done it before on an MS-DOS computer was that no one had ever been hugely motivated to try, in light of the types of games that were generally accepted as “appropriate” for that platform; technological determinism is a potent force in game development, but it’s never the only force. And I should also note a certain irony that clings to all this. As we’ll see, John Carmack would soon toll the death knell for the era of bouncing sprites superimposed over scrolling 2D backgrounds. How odd that his first great eureka moment should have come in imitation of just that classic videogame style.

Carmack first showed his innovation to Tom Hall, the biggest Super Mario fan of all among the id boys, late in the afternoon of September 20, 1990. Hall recognized its significance immediately, and suggested that he and Carmack recreate some of the first level of Super Mario Bros. 3 right then and there as a proof of concept. They finally stumbled off to bed at 5:30 the following morning.

A few hours later, John Romero woke up to find a floppy disk sitting on his keyboard. He popped it into the drive, and his jaw hit the floor when he saw a Nintendo game playing there on his computer monitor. He went off to find Jay Wilbur and Adrian Carmack. They all agreed that this was big — way too big for the likes of Softdisk.

In one 72-hour marathon, the id boys recreated all of the first level of Super Mario Bros. 3, along with bits and pieces of those that followed. Then Wilbur typed up a letter to Nintendo of America and dropped it in the mail along with the disk; it said that the id boys were ready and willing to license their PC port of Super Mario Bros. 3 back to the Nintendo mother ship. This was a profoundly naïve thing to do; virtually anyone in the industry could have told them that Nintendo never let any of their intellectual property escape from the walled garden of their own console. And sure enough, the id boys would eventually receive a politely worded response saying no thank you. Given Nintendo’s infamous ruthlessness when it came to matters of intellectual property, they were probably lucky that a rejection letter was all they received, rather than a lawsuit.

At any rate, the id boys weren’t noted for their patience. Long before Nintendo’s response arrived, they would be on to the next thing: an original game using John Carmack’s scrolling technique.

For some time now, John Romero had been receiving fawning fan mail care of Softdisk, not a usual phenomenon at all. His gratification was lessened somewhat, however, by the fact that the letters all came from the same address near Dallas, Texas, all asked him to call the fan in question at the same phone number, and were all signed with suspiciously similar names: “Byron Muller,” “Scott Mulliere,” etc.

It was in fact our old friend Scott Miller. His attention had been captured by Romero’s games for On Disk and Gamer’s Edge; they would be perfect for Apogee, he thought. But how to get in touch? The only contact information he had was that of Softdisk’s main office. He could hardly write them a letter asking if he could poach one of their programmers. His solution was this barrage of seemingly innocent fan mail. Maybe, just maybe, Romero really would call him…

Romero didn’t call, but he did write back, and included his own phone number. Miller rang it up immediately. “Fuck those letters!” he said when Romero started to ask what kind of prank he thought he was pulling. “We can make a ton of money together selling your games as shareware.”

“Dude, those old games are garbage compared to the stuff we can make now,” said Romero, with John Carmack’s new scrolling technique firmly in mind. They struck a deal: Miller would send the id boys an advance of $2000, and they would send him a brand-new three-part game as soon as possible.

The Gamer’s Edge magazine, which just six months ago had seemed like the perfect job, now fell to the back burner in light of the riches Miller was promising them. Since they were making a Nintendo-like game in terms of action, it seemed logical to copy Nintendo’s bright and cheerful approach in the new game’s graphics and fiction as well. This was Tom Hall’s moment to shine; he already seemed to live every day in just such a primary-colored cartoon fantasy. Now, he created an outline for Commander Keen, blending Nintendo with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and old science-fiction serials — the last being perfect for an episodic game.

Billy Blaze, eight-year-old genius, working diligently in his backyard clubhouse, has created an interstellar spaceship from old soup cans, rubber cement, and plastic tubing. While his folks are out on the town and the babysitter is asleep, Billy sneaks out to his backyard workshop, dons his brother’s football helmet, and transforms into… Commander Keen, Defender of Justice! In his ship, the Bean with Bacon Megarocket, Keen dispenses justice with an iron hand!

In this episode, aliens from the planet Vorticon VI find out about the eight-year-old genius and plan his destruction. While Keen is out exploring the mountains of Mars, the Vorticons steal his ship and leave pieces around the galaxy! Can Keen recover all the pieces of his ship and repel the Vorticon invasion? Will he make it back before his parents get home? Stay tuned!

Commander Keen

When Miller received the first Commander Keen trilogy in the post barely two months later, he was thrilled beyond his wildest dreams. He had known that the id boys were talented, but this… he had never imagined this. This wasn’t a throwback to the boxed games of yore, wasn’t even on a par with the boxed games of current times. It was something entirely different, something never seen on an MS-DOS computer at all before, as visually striking and technically innovative within its chosen sphere as any of the latest boxed games were within theirs. Just like that, shareware games had come of age.

All of Apogee’s games together had been earning about $7000 per month. Commander Keen alone made $20,000 in the first month of its availability. It caused such a stir online that the established industry took a casual notice for the first time of this new entity called Apogee with this odd new way of selling games. Computer Gaming World magazine even deigned to give Commander Keen a blurb in the new-releases section. It was “of true commercial quality,” they noted, only slightly condescendingly.

Despite their success in shareware and the big checks that started coming in the mail from Apogee as a result, the id boys continued to make games for Gamer’s Edge throughout 1991. Betwixt and between, they provided Miller with a second Commander Keen trilogy, which did every bit as well as the first. No one could ever accuse them of being lazy.

But making a metaphorical name for themselves outside of Softdisk meant that they needed a literal name for the world to know them by. When they had sent their Super Mario Bros. 3 clone to Nintendo, they had called themselves “Ideas from the Deep.” Deciding that was too long-winded, they became “ID” when they started releasing games with Apogee — short for “In Demand.” The only one of their number who cottoned onto the Freudian implications of the acronym was Jay Wilbur; none of the other id boys knew Sigmund Freud from Siegmund the Norse hero. But when Wilbur explained to them how Freud’s id was the seat of a person’s most basic, impulsive desires, they were delighted. By this happenstance, then, id Software got a name which a thousand branding experts could never have bettered. It encapsulated perfectly their mission to deconstruct computer gaming, to break it down into a raw essence of action and reaction. The only ingredient still missing from the eventual id Software formula was copious violence.

And that too was already in the offing: Tom Hall’s cheerful cartoon aesthetic had started to wear thin with John Romero and Adrian Carmack long before they sent the first Commander Keen games to Scott Miller. Playing around one day with some graphics for the latest Gamer’s Edge production, Adrian drew a zombie clawing out the eyes of the player’s avatar, sending blood and gore flying everywhere. Romero loved it: “Blood! In a game! How fucking awesome is that?”

Adrian’s reply was weirdly pensive. “Maybe one day,” he said in a dreamy voice, “we’ll be able to put in as much blood as we want.”

In September of 1991, the id boys’ lease on their riverside frat house expired, and they decided that it was time to leave the depressing environs of Shreveport, with its crime, its poverty, and its homeless population who clustered disturbingly around the Softdisk offices. Their contract stipulated that they still owed Gamer’s Edge a few more games, but Al Vekovius had long since given up on trying to control them. The id boys decamped for Madison, Wisconsin, at the suggestion of Tom Hall, who had attended university there. He promised them with all of his usual enthusiasm that it was the best place ever. Instead they found the Wisconsin winter to be miserable. Cooped up inside their individual apartments, missing keenly their big old communal house and their motorboat, they threw themselves more completely than ever into making games. Everyone, with the exception only of Tom Hall, was now heartily sick and tired of Commander Keen. It was time for something new.

Whilst working at Origin Systems in the late 1980s, John Romero had met Paul Neurath, who had since gone on to start his own studio known as Blue Sky Productions. During their occasional phone calls, Neurath kept dropping hints to his friend about the game his people were working on: an immersive first-person CRPG, rendered using texture-mapped 3D graphics. When Romero mentioned it to John Carmack, his reply was short, as so many of them tended to be: “Yeah, I can do that.”

Real-time 3D graphics in general were hardly a new development. Academic research in the field stretched back to well before the era of the microchip. Bruce Artwick had employed them in the original Radio Shack TRS-80 Flight Simulator in 1980, and Ian Bell and David Braben had used them in Elite in 1984; both games were among the best sellers of their decade. Indeed, the genre of vehicular simulations, one of the most popular of them all by the late 1980s, relied on 3D graphics almost exclusively. All of which is to say that you didn’t have to look very hard in your local software store to find a 3D game of some stripe.

And yet, according at least to the conventional wisdom, the limitations of 3D graphics made them unsuitable for the sort of visceral, ultra-fast-paced experience which the id boys preferred. All of the extra affordances built into gaming-oriented platforms like the NES to enable 2D sprite-based graphics were useless for 3D graphics. 3D required radical compromises in speed or appearance, or both: those early versions of Flight Simulator were so slow that it could take the program a full second or two to respond to your inputs, which made flying their virtual airplanes perversely more difficult than flying the real thing; Elite managed to be more responsive, but only by drawing its 3D world using wire-frame outlines instead of filled surfaces. The games-industry consensus was that 3D graphics had a lot of potential for many types of games beyond those they were currently being used for, but that computer hardware was probably five to ten years away from being able to realize most of it.

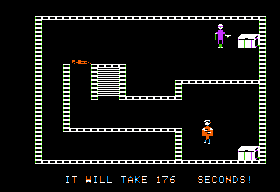

John Carmack wasn’t that patient. If he couldn’t make true 3D graphics run at an acceptable speed in the here and now, he believed that he could fake it in a fairly convincing way. He devised a technique of presenting a fundamentally 2D world from a first-person perspective. Said world was a weirdly circumscribed place to inhabit: all angles had to be right angles; all walls had to stretch uniformly from floor to ceiling; all floors and ceilings had to be colored in the same uniform gray. Only interior scenes were possible, and no stairways, no jumping, no height differences of any kind were allowed; in this egalitarian world, everything and everyone had to stay permanently on the same level. You weren’t even allowed to look up or down. But, limited though it was, it was like nothing anyone had ever seen.

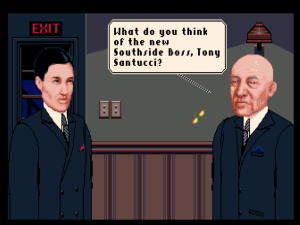

“You know,” said John Romero one day when they were all sitting around discussing what to do with the new technology, “it’d be really fucking cool if we made a remake of Castle Wolfenstein and did it in 3D.” With those words, id’s next game was born, one that would make all the success of Commander Keen look like nothing.

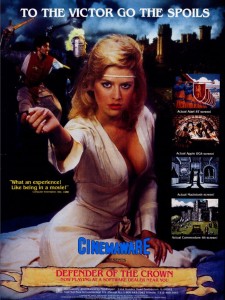

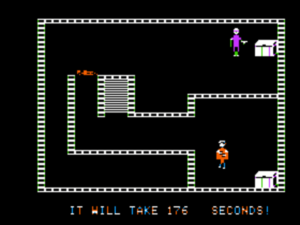

The original Castle Wolfenstein.

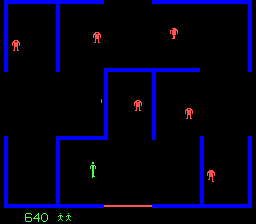

Written by Silas Warner, one of the Apple II scene’s early superstar programmers, and published by the long-defunct Muse Software, Castle Wolfenstein was an established classic from 1981, a top-down action-adventure that cast you as a prisoner of the Nazis who must escape, preferably taking his captors’ secret war plans with him. It remains historically notable today for incorporating a significant stealth component; ammunition was scarce and your enemies tough, which often made avoidance a better strategy than confrontation.

But avoidance wasn’t the id boys’ style. Very early on, they jettisoned everything beyond the core theme of the original Castle Wolfenstein. Wolfenstein 3D was to be, as Romero put it, “a totally shocking game. There should be blood, lots of blood, blood like you never see in games. When the player gets really low in health, at like 10 percent, he could run over the bloody guts of a dead Nazi soldier and suck those up for extra energy. It’s like human giblets. You can eat up their gibs!” In other words, Tom Hall’s aesthetic vision was out; John Romero and Adrian Carmack’s was in. “Hey, you know what we should have in here? Pissing! We should make it so you can fucking stop and piss on the Nazi after you mow him down! That would be fucking awesome!”

In early 1992, the id boys came face to face with the gaming establishment for the first time thanks to Wolfenstein 3D. They sent an early demo of the game to Sierra, and that company’s founder and CEO Ken Williams invited them to fly out to California and have a chat. Sierra was one of the three biggest computer-game publishers in the world, and was at the forefront of the interactive-movie trend which the id boys loathed. King’s Quest VI, the upcoming new installment in Sierra’s flagship series, would be so weighted down with multimedia that most reviewers, hopelessly dazzled, could spare only a few sentences for the rather rote little adventure game underneath it all. Williams himself was widely recognized as one of the foremost visionaries of the new era, proclaiming that by the end of the decade much or most of the Hollywood machine would have embraced interactivity. A meeting between two more disparate visions of gaming than his and that of the id boys can scarcely be imagined.

And yet the meeting was a cordial one on the whole. Williams had been quick to recognize when he saw Wolfenstein 3D that id had some remarkable technology, while the id boys remembered the older Apple II games of Sierra fondly. Williams took them on a tour of the offices where many of those games had come from, and then, after lunch, offered to buy id Software for $2.5 million in Sierra stock. The boys discussed it for a bit, then asked for an additional $100,000 in cash. Williams refused; he was willing to move stock around to pay for the Wolfenstein 3D technology, but he wasn’t willing to put his cash on the table. So, the negotiation ended. Instead Williams bought Bright Star Technologies, a specialist in educational software, for $1 million in cash later that year — for educational software, he believed, would soon be bigger than games. Time would prove him to be as wrong about that as he was about the future of Hollywood.

Not long after the Sierra meeting, the id boys left frigid Wisconsin in favor of Dallas, Texas, home of Scott Miller, who had been telling them about the warm weather, huge lakes, splendid barbecue, and nonexistent state income tax of the place for more than eighteen months now. One Kevin Cloud, who had held the oft-thankless role of being the id boys’ liaison with Softdisk but also happened to be a talented artist, joined them in Dallas as a sixth member of their little collective, thereby to relieve some of the burden on Adrian Carmack.

After making the move, they broke the news to Softdisk that they wouldn’t be doing Gamer’s Edge anymore. Al Vekovius was disappointed but not devastated. Oddly given how popular Commander Keen had become, the gaming disk magazine had never really taken off; it still only had about 3000 subscribers.

And so Softdisk Publications of Shreveport, Louisiana, that unlikely tech success story in that most unlikely of locales, finally exits our story permanently at this point. Nothing if not a survivor, Vekovius would keep the company alive through the 1990s and beyond by transitioning into the next big thing in computing: he turned it into an Internet service provider. He was bought out circa 2005 by a larger regional provider.

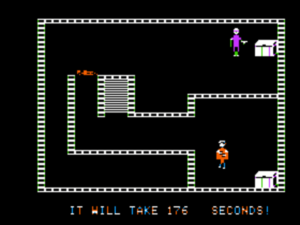

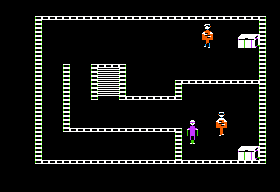

Wolfenstein 3D

This screenshot of the Wolfenstein 3D map editor illustrates why the game’s name is a misnomer: the environment is really a 2D maze much like that of the original game, albeit shown from a first-person perspective. At bottom, the engine understands just two dimensions rather than three.

If the id boys were worried about how Scott Miller would react to the ultra-violence of Wolfenstein 3D, they needn’t have been. Apogee had already been moving in this direction with considerable success; their only game to rival Commander Keen in sales during 1991 had been Duke Nukum by Todd Replogle, whose titular protagonist was a cigar-chomping Arnold Schwarzenegger facsimile with a machine gun almost as big around as his biceps. When Miller saw Wolfenstein 3D for the first time, he loved the violence as much as he did John Carmack’s pseudo-3D graphics engine. He knew what his customers craved, and he knew that they would swoon over this. He convinced the id boys to make enough levels to release a free episode followed by five paid ones rather than the usual two. On May 5, 1992 — the very same day on which the boys had handed the final version to Miller — the free installment appeared on Software Creations, Apogee’s new online service.

As it happened, Paul Neurath’s Blue Sky Productions had released their own immersive first-person 3D game, which had spent roughly five times as long in production as Wolfenstein 3D, just two months before. It was called Ultima Underworld, and was published as a boxed product by Origin Systems. It boasted a far more complete implementation of a 3D world than did id’s creation. You could look up, down, and all around; could jump and climb ledges; could sneak around corners and hide in shadows; could swim in rivers or fly through the air by means of a levitation spell. But Ultima Underworld was cerebral, old school — dull, as the id boys and many of their fan base saw it. Combat was only a part of its challenge. You also had to spend your time piecing together clues, collecting spells, solving puzzles, annotating maps, leveling up and assigning statistics and skills to your character. Even the combat happened at a speed most kindly described as “stately” if you didn’t have a cutting-edge computer.

Wolfenstein 3D, by contrast, ran like greased lightning on just about any computer, thanks to John Carmack’s willingness to excise any element from his graphics engine that he couldn’t render quickly. After all, the id boys really only wanted to watch the blood spurt as they mowed down Nazis; “just run over everything and destroy” was their stated design philosophy. And many others, it seemed, agreed with their point of view.

For, while Ultima Underworld became a substantial hit, Wolfenstein 3D became a phenomenon. It made $200,000 in the first month, then kept selling at that pace for the next eighteen months. It was, as Scott Miller would later put it, a “paradigm shift” in shareware games. Whatever that elusive “it” was that so many gamers found to be missing in the big boxed offerings — immediacy? simplicity? violence? id in the Freudian sense? all of the above? — Wolfenstein 3D had it in spades.

The shareware barbarians were truly at the gates now; they could no longer be ignored by the complacent organs of the establishment. This time out, id got a feature review in Computer Gaming World to go along with the full-page color advertisements which Apogee was now able to pay for. “I can’t remember a game making such effective use of perspective and sound and thereby evoking such intense physiological responses from its player,” the review concluded. “I recommend gamers take a look at this one, if only for a cheap peek at part of interactive entertainment’s potential for a sensory-immersed ‘virtual’ future.”

Yet, as that “if only” qualifier intimates, the same magazine was clearly bothered by all of the gleefully gory violence of the game. An editorial by editor-in-chief Johnny Wilson, the former pastor who had built Computer Gaming World into the most thoughtful and mature journal in the industry, drove the point home: “What are we saying when we depict lifelike carnage in a game where the design is geared for you to kill nearly everyone you encounter?”

If Wilson thought id’s first 3D shooter was disturbing, he hadn’t seen anything yet. Their next game would up the ante on the violence and gore even as their first competitors jumped into the act, starting a contest to see who could be most extreme. Everyone working in games or playing them would soon have to reckon with the changes — distributional, technical, and cultural — which a burgeoning new genre, born on the streets instead of in the halls of power, was wreaking.

Crashing the halls of power: Tom Hall, Jay Wilbur, and John Romero in black tie for the Shareware Industry Awards of 1992.

(Sources: the books Masters of Doom by David Kushner, Game Engine Black Book: Wolfenstein 3D by Fabien Sanglard, Principles of Three-Dimensional Computer Animation by Michael O’Rourke, Sophistication & Simplicity: The Life and Times of the Apple II Computer by Steven Weyhrich, and I Am Error by Nathan Altice; PC Magazine of September 12 1989; InfoWorld of June 12 1989; Retro Gamer 75; Game Developer premiere issue and issues of June 1994 and February/March 1995; Computer Gaming World of August 1991, January 1992, August 1992, and September 1992; The Computist 88; inCider of November 1989. Online sources include “Apogee: Where Wolfenstein Got Its Start” by Chris Plante at Polygon, “Rocket Jump: Quake and the Golden Era of First-Person Shooters” by David L. Craddock at Shack News, Samuel Stoddard’s Apogee FAQ, Benj Edwards’s interview with Scott Miller for Game Developer, Jeremy Peels’s interview with John Romero for PC Games N, Lode Vandevenne’s explanation of the Wolfenstein 3D rendering engine, and Jay Wilbur’s old Usenet posts, which can now be accessed via Google Groups.

The company once known as Apogee, which is now known as 3D Realms, has released many of their old shareware games for free on their website, including Commander Keen. All of the Wolfenstein 3D installments are available as digital purchases at GOG.com.)