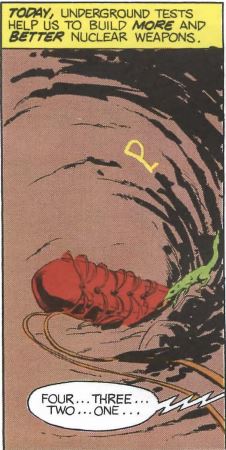

Underground

You're in a narrow underground chamber, illuminated by an open door in the east wall. The walls and ceiling are gouged with deep spiral ruts; they look as if they've been routed out with heavy machinery.

A large cylinder occupies most of the chamber. The maze of cables and pipes surrounding it trails west, into the depths of a tunnel.

>w

Underground

The cables and pipes lining the tunnel's walls look like bloated veins and arteries in the splinter's flickering glow. Deep tunnels bend off to the east and west.

Some careless technician has left a walkie-talkie lying in the dirt.

>get walkie-talkie

Taken.

>turn on walkie-talkie

You turn on the rocker switch.

>z

Time passes.

A tinny voice, half-buried in static, says "Two."

>z

Time passes.

"One."

>z

Time passes.

The walkie-talkie clicks and hisses.

>z

Time passes.

For a brief moment, the tunnel is bathed in a raw white glare.

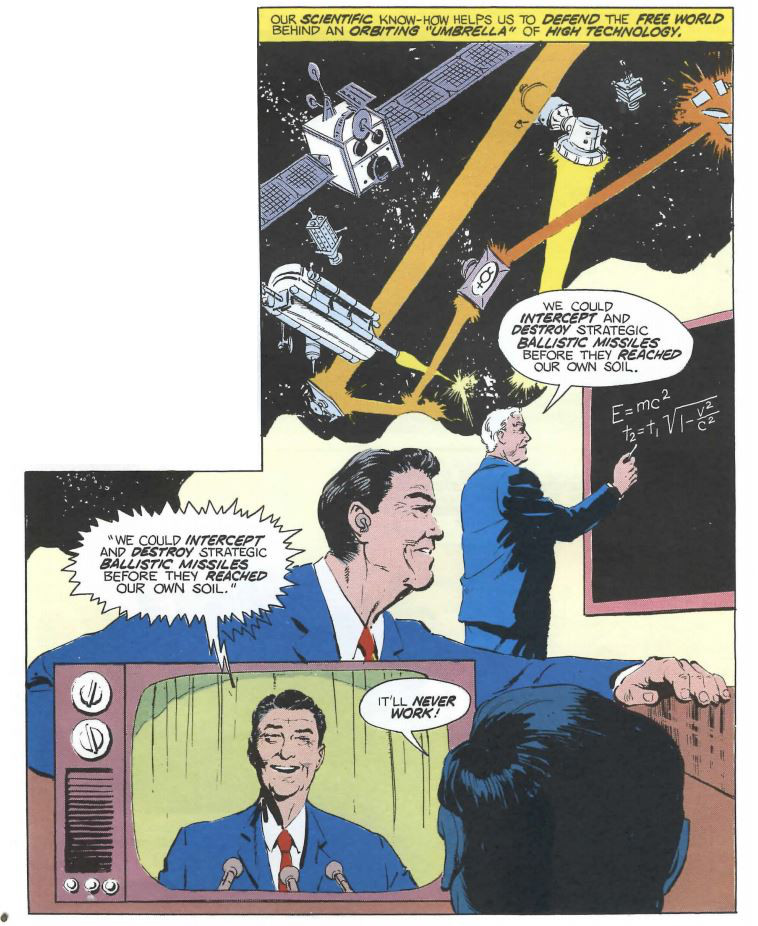

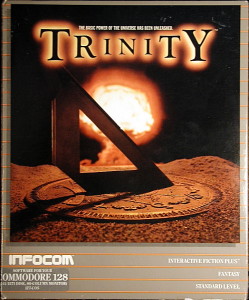

The most subtly chilling vista in Trinity is found not inside one of its real-world atomic vignettes, but rather in the magical land that serves as the central hub for your explorations. This landscape is dotted with incongruous giant toadstools, each of which, you eventually realize, represents a single atomic explosion.

As your eyes sweep the landscape, you notice more of the giant toadstools. There must be hundreds of them. Some sprout in clusters, others grow in solitude among the trees. Their numbers increase dramatically as your gaze moves westward, until the forest is choked with pale domes.

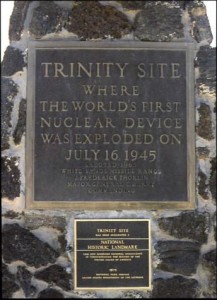

The scene is a representation of time, following the path of the sun from east to west. The toadstools choking the forest to the west presumably represent the nuclear apocalypse you’ve just escaped. If we subtract those toadstools along with the two somewhere far off to the east that must represent the Hiroshima and Nagasaki blasts, we’re left with those that represent not instances of atomic bombs used in anger, but rather tests. A few of these we know well as historical landmarks in their own right: the first hydrogen bomb; the first Soviet bomb; that original Trinity blast, off far to the southeast with the rising sun, from which the game takes its name and where its climax will play out. Like the bombs used in anger, these don’t interest us today; we’ll give them their due in future articles. What I do want to talk about today is some of the blasts we don’t usually hear so much about. As the landscape would indicate, there have been lots of them. Since the nuclear era began one summer morning in the New Mexico desert in 1945, there has been a verified total of 2119 tests of nuclear bombs. Almost half of that number is attributed to the United States alone. Yes, there have been a lot of bombs.

At the close of World War II, the big question for planners and politicians in the United States was that of who should be given control of the nation’s burgeoning nuclear arsenal. The Manhattan Project had been conducted under the ostensible auspices of the Army Air Force (the Air Force wouldn’t become its own independent service branch until 1947), but in reality had been something of a law unto itself. Now both Army and Navy were eager to lay claim to the bomb. The latter had dismissed the bomb’s prospects during the war years and declined to play any role in the Manhattan Project, but was nevertheless able to wrangle enough control now to be given responsibility for the first post-war tests of the gadgets, to be called Operation Crossroads. The tests’ announced objective was to determine the impact of the atomic bomb on military ships. Accordingly, the Navy assembled for atomic target practice around Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands a fleet made up of surplus American ships and captured German and Japanese that would have been the envy of most other nations. Its 93 vessels included in their ranks 2 aircraft carriers, 5 battleships, and 4 cruisers. The 167 native residents of Bikini were shipped off to another, much less survivable island, first stop in what would prove to be a long odyssey of misery. (Their sad story is best told in Operation Crossroads by Jonathan M. Weisgall.)

From the start, Operation Crossroads had more to do with politics than with engineering or scientific considerations. It was widely hyped as a “test” to see if the very idea of a fighting navy still had any relevance in this new atomic age. More importantly in the minds of its political planners, it would also be a forceful demonstration to the Soviet Union of just what this awesome new American weapon could do. Operation Crossroads was the hottest ticket in town during the summer of 1946. Politicians, bureaucrats, and journalists — everyone who could finagle an invitation — flocked to Bikini to enjoy the spectacle along with good wine and food aboard one of the Navy’s well-appointed host vessels, swelling the number of on-site personnel to as high as 40,000.

Unprotected sailors aboard the German cruiser Prinz Eugen just hours after it was irradiated by an atomic bomb.

The spectators would get somewhat less than they bargained for, many of the sailors considerably more. The first bomb was dropped from a borrowed Army Air Force B-29 because the Navy had no aircraft capable of carrying the gadget. Dropped on a hazy, humid morning from high altitude, from which level the B-29 was notoriously inaccurate even under the best conditions, the bomb missed the center of the doomed fleet by some 700 yards. Only two uninteresting attack transports sank instantly in anything like the expected spectacular fashion, and only five ships sank in total, the largest of them a cruiser. As the journalists filed their reams of disappointed copy and the Navy’s leadership breathed a sigh of relief, some 5000 often shirtless sailors were dispatched to board the various vessels inside the hot zone to analyze their damage; as a safety precaution, they first scrubbed them down using water, soap, and lye to get rid of any lingering radiation. The operation then proceeded with the second bomb, an underwater blast that proved somewhat more satisfying, ripping apart the big battleship Arkansas and the aircraft carrier Saratoga amongst other vessels and tossing their pieces high into the air.

Operation Crossroads was emblematic of a Navy leadership that had yet to get their collective heads around just what a paradigm-annihilating device the atomic bomb actually was. Their insistence on dropping it on warships, as if the future was just going to bring more Battles of Midway with somewhat bigger explosions, shows that they still thought of the atomic bomb as essentially just a more powerful version of the bombs they were used to, a fundamentally tactical rather than strategic device. Their complete failure to take seriously the dangers of radioactive fallout, meanwhile, may be the reason that the sailors who took part in Operation Crossroads suffered an average life-span reduction of three months compared to others in their peer group. These were early days yet in atomic physics, but their state of denial is nevertheless difficult to understand. If the horrific photographs and films out of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — some of which apparently are shocking enough to still be classified — hadn’t been warning enough, there was always the case of Los Alamos physicist Louis Slotin. Less than six weeks before Operation Crossroads began, Slotin had accidentally started a chain reaction while experimenting with the atomic core of the same type of bomb used in the tests. He stopped the reaction through quick thinking and bravery, but not before absorbing a lethal dose of radiation. His slow, agonizing death — the second such to be experienced by a Los Alamos physicist — was meticulously filmed and documented, then made available to everyone working with atomic weapons. And yet the Navy chortled about the failure of the atomic bomb to do as much damage as expected whilst cheerfully sending in the boys to do some cleanup, ignoring both the slowly dying goats and other animals they had left aboard the various ships and the assessment of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists of the likely fate of any individual ship in the target fleet: “The crew would be killed by the deadly burst of radiation from the bomb, and only a ghost ship would remain, floating unattended in the vast waters of the ocean.”

Just as President Eisenhower would take space exploration out from under the thumb of the military a decade later with the creation of NASA, President Truman did an end-run around the military’s conventional thinking about the atomic bomb on January 1, 1947, when the new, ostensibly civilian Atomic Energy Commission took over all responsibility for the development, testing, and deployment of the nation’s atomic stockpile. The Atomic Energy Commision would continue to conduct a steady trickle of tests in the remoter reaches of the Pacific for many years to come, albeit none with quite the bizarre spectator-sport qualities of Operation Crossroads. But the twin shocks of the first Soviet test of an atomic bomb on August 29, 1949, and the beginning of the Korean War in 1950, which came equipped with a raging debate about whether, how, and when the United States should again use its nuclear arsenal in anger, led weapons developers to agitate for a more local test site where they could regularly and easily set off smaller weapons than the blockbusters that tended to get earmarked to the Pacific. There were, they argued, plenty of open spaces in the American Southwest that would suit such a purpose perfectly well. On December 18, 1950, Truman therefore approved the allocation for this purpose of a 680-square-mile area inside the vast Nellis Air Force Gunnery and Bombing Range in the Nevada desert some 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas. The first test there, marking the first atomic bomb to be exploded on American soil since the original Trinity device, took place astonishingly soon thereafter, on January 27, 1951. By the end of the year sleeping quarters, mess halls, and laboratories had been built, creating a functioning, happy little community dedicated to making ever better bombs. The saga of the Nevada Test Site had begun. In the end no fewer than 928 of the 1032 nuclear tests ever conducted by the United States would be conducted right here.

The strangest years of this very strange enterprise were the earliest. With money plentiful and the need to keep ahead of the Soviets perceived as urgent, bombs were exploded at quite a clip — twelve during the first year alone. At first they were mostly dropped from airplanes, later more commonly hung from balloons or mounted atop tall temporary towers. The testing regime was, as test-site geophysicist Wendell Weart would later put it, very “free-form.” If someone at one of the nation’s dueling atomic-weapons laboratories of Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos determined that he needed a “shot” to prove a point or answer a question, he generally got it in pretty short order. Whatever else the testing accomplished, it was also a hell of a lot of fun. “I guess little boys like fireworks and firecrackers,” Weart admits, “and this was the biggest set of fireworks you could ever hope to see.” Las Vegas residents grew accustomed to the surreal sight of mushroom clouds blooming over their cityscape, like scenes from one of the B-grade atomic-themed monsters movies that filled the theaters of the era. When the bombs went off at night, they sometimes made enough light to read a newspaper by.

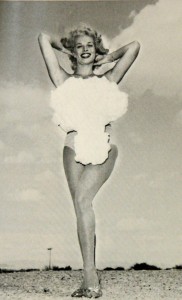

This era of free-form atmospheric testing at the Nevada Test Site coincided with the era of atomic mania in the United States at large, when nuclear energy of all stripes was considered the key to the future and the square-jawed scientists and engineers who worked on it veritable heroes. The most enduring marker of this era today is also one of the first. In 1946, not one but two French designers introduced risqué new women’s bathing suits that were smaller and more revealing than anything that had come before. Jacques Heim called his the “atome,” or atom, “the world’s smallest bathing suit.” Louis Réard named his the bikini after the recently concluded Operation Crossroads tests at Bikini Atoll. “Like the bomb,” he declared, “the bikini is small and devastating.” It was Réard’s chosen name that stuck. In addition to explosive swimwear, by the mid-1950s you could get a “Lone Ranger atomic-bomb ring” by sending in 15 cents plus a Kix cereal proof of purchase; buy a pair of atomic-bomb salt and pepper shakers; buy an “Atomic Disintegrator” cap gun. Trinity‘s accompanying comic book with its breathless “Atomic Facts: Stranger than Fiction!” and its hyperactive patriotism is a dead ringer for those times.

Said times being what they were, Las Vegas denizens, far from being disturbed by the bombs going off so close by, embraced them with all of their usual kitschy enthusiasm. The test site helpfully provided an annual calendar of scheduled tests for civilians so they could make plans to come out and enjoy the shows. For children, it was a special treat to drive up to one of the best viewpoints on Mount Charleston early in the morning on the day of a shot, like an even better version of the Fourth of July; the budding connoisseurs cataloged and ranked the shots and compared notes with their friends in the schoolyard. Many adults, being connoisseurs of another stripe, might prefer the “Miss Atomic Bomb” beauty pageants and revues that were all the rage along the Strip.

The official government stance, at the time and to a large extent even today, is that the radioactive fallout from these explosions traveled little distance if at all and was in any case minor enough to present few to no health or environmental concerns. Nevertheless, ranchers whose sheep grazed in the vicinity of the test site saw their flocks begin to sicken and die very soon after the test shots began. They mounted a lawsuit, which was denied under somewhat questionable circumstances in 1956; the sheep, claimed the court, had died of “malnutrition” or some other unidentified sickness. That judgment, almost all of the transcripts from which have since been lost, was later overturned on the rather astonishing basis of outright “fraud on the court” by the government’s defense team. That judgment was in its turn vacated on appeal in 1985, more than thirty years after the events in question. Virtually all questions about the so-called “Downwinders” who were affected — or believe they were affected — by fallout from the test site seem to end up in a similarly frustrating tangle.

What does seem fairly clear amid the bureaucratic babble, from circumstantial evidence if nothing else, is that the government even in the 1950s had more awareness of and concerns about fallout from the site than they owned up to publicly. Radioactive debris from those very first tests in early 1951 was detected, according to test-site meteorologist Philip Wymer Allen, going “up over Utah and across the Midwest and Illinois, not too far south of Chicago, and out across the Atlantic Coast and was still easily measured as the cloud passed north of Bermuda. We didn’t track it any further than that.” Already in 1952 physical chemist Willard Libby, inventor of radiocarbon dating and later a member of the Atomic Energy Commission, was expressing concerns about radioactive cesium escaping the site and being absorbed into the bones of people, especially children. A potential result could be leukemia. Another, arguably even graver concern, was radioiodine particles, which could be carried a surprising distance downwind before settling to earth, potentially on the forage preferred by sheep, goats, and cows. Many people in rural communities, especially in those days, drank unprocessed milk straight from the cow, as it were. If enough milk containing radioiodine is ingested, it can lead to thyroid cancer. Children were, once again, both particularly big drinkers of milk and particularly prone to the effects of the radioiodine that might be within it. When environmental chemist Delbert Barth was hired in the 1960s to conduct studies of radioiodine dispersion patterns at the site, he was asked to also make historical projections for the atmospheric shots of the 1950s — a request that, at least on its surface, seems rather odd if everyone truly believed there was absolutely nothing to fear. Similarly odd seems a policy which went into effect very early: not to conduct shots if the winds were blowing toward Las Vegas.

The radioactive exposure — or lack thereof — of the Downwinders remains a major political issue inside Nevada and also Utah, which many claim also received its fair share of fallout. Most people who were associated with the site say, predictably enough, that the Downwinders are at best misguided and at worst would-be freeloaders. Studies have not established a clear causal link between incidences of cancer and proximity to the Nevada Test Site, although many, including Barth, have expressed concerns about the methodologies they’ve employed. What we’re left with, then, are lots of heartbreaking stories which may have been caused by the activities at the site or may represent the simple hand of fate. (For a particularly sad story, which I won’t go into here because I don’t want to sound exploitative, see this interview with Zenna Mae and Eugene Bridges.)

The first era of the Nevada Test Site came to an abrupt end in November of 1958, when the United States and the Soviet Union entered into a non-binding mutual moratorium on all sorts of nuclear testing. For almost three years, the bombs fell silent at the test site and at its Soviet equivalent near Semipalatinsk in Kazakhstan. But then, on September 1, 1961, the Soviets suddenly started testing again, prompting the Nevada Test Site to go back into action as well. Still, the public was growing increasingly concerned over what was starting to look like the reckless practice of atmospheric testing. While Las Vegas had continued to party hearty, even before the moratorium the doughty farmers and ranchers working still closer to the site had, as Lawrence Livermore physicist Clifford Olsen rather dismissively puts it, “started to grumble a bit” about the effect they believed the fallout was having on their animals and crops and possibly their own bodies and those of their children. And now an international environmentalist movement was beginning to arise in response to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. In one of his last major acts before his assassination, President Kennedy in October of 1963 signed along with Soviet First Secretary Khrushchev the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty that required all future nuclear tests to take place underground.

But never fear, the good times were hardly over at the Nevada Test Site. The scientists and engineers there had been experimenting with underground explosions for some years already in anticipation of this day that the more politically aware among them had begun to see as inevitable. Thus they were more than prepared to continue full-speed-ahead with a new regime of underground testing. The number of shots actually increased considerably during the 1960s, often clipping along at a steady average of one per week or more. Las Vegas, meanwhile, was still not allowed to forget about the presence of the test site. Residents grew accustomed to tremors that cracked plaster and made high-rises sway disconcertingly, phenomena that came to be known as “seismic fallout.” As the political mood shifted over the course of the decade, the number of complaints grew steadily, especially after a couple of big shots of well over 1 megaton in 1968 that caused serious structural damage to a number of buildings in Las Vegas. One of the most persistent and vociferous of the complainers was the eccentric billionaire recluse Howard Hughes, who was living at the time on the top two floors of the Desert Inn hotel. Hughes marshaled lots of money, employees, and political connections to his cause during the late 1960s, but was never able to stop or even slow the testing.

As for the environmental impact of this new breed of underground tests, the news is mixed. While neither is exactly ideal, it’s obviously preferable from an environmental standpoint to be exploding atomic bombs underground rather than in the open air. A whole new applied sub-science of geophysics, the discipline of nuclear “containment,” evolved out of efforts to, well, contain the explosions — to keep any radioactive material at all from “venting” to the surface during an explosion or “seeping” to the surface during the hours, months, and years afterward. And yet the attitudes of the folks working on the shots can still sound shockingly cavalier today. About 30 percent of the underground tests conducted during the 1960s leaked radioactivity to the surface to one degree or another. Those working at the site considered this figure acceptable. Virtually everyone present there during the 1960s makes note of the positive, non-bureaucratic, “can-do” attitude that still persisted into this new era of underground testing. Linda Smith, an administrator at the site, characterizes the attitude thus: “There is such a strong bias to get it done that overrides everything. Is there any profound discussion of should we or shouldn’t we? Is this good for the country? Is it not? There’s no question. You are there to get it done.” Clifford Olsen says, “We were all pretty much sure we were doing the right thing.”

What to make of this lack of introspection? Whatever else we say about it, we shouldn’t condemn the people of the Nevada Test Site too harshly for it. There were heaps of brilliant minds among them, but their backgrounds were very different from those of the people who had worked on the Manhattan Project, many of whom had thought and agonized at length about the nature of the work they were doing and the unimaginable power they were unleashing on the world. The men and few women of the Nevada Test Site, by contrast, had mostly come of age during or immediately after World War II, and had been raised in the very bosom of the burgeoning military-industrial complex. Indeed, most had had their education funded by military or industrial backers for the singular purpose of designing and operating nuclear weapons. This set them apart from their predecessors, who before the Manhattan Project and to a large degree after it — many among that first generation of bomb-makers considered their work in this area essentially done once the first few bombs had been exploded — tended to focus more on “pure” science than on its practical application. A few Brits aside, the Nevada Test Site people were monolithically American; many on the Manhattan Project came from overseas, including lots of refugees from occupied Europe. The Nevada Test Site people were politically conservative, in favor of law and order and strong defense (how could they not be given the nature of their work?); the Manhattan Project people were a much more politically heterogeneous group, with a leader in Robert Oppenheimer who had worked extensively for communist causes. Someone with a background like his would never have been allowed past the front gate of the Nevada Test Site.

Whatever else it was, the Nevada Test Site was just a great place to work. Regarded as they were as the nation’s main bulwark against the Soviet Union, the atomic scientists and all of those who worked with and supported them generally got whatever they asked for. Even the chow was first-rate: at the cafeteria, a dollar would get you all the steaks — good steaks — that you could eat. When all the long hours spent planning and calculating got to be too much, you could always take in a movie or go bowling: a little self-contained all-American town called Mercury grew up with the test site there in the middle of the desert. Its population peaked at about 10,000 during the 1960s, by which time it included in addition to a movie theater and bowling alley a post office, schools, churches, a variety of restaurants, a library, a swimming hall, and hotels — including one named, inevitably, the Atomic Motel. Or you could always take a walk just outside of town amidst the splendid, haunting desolation of the Nevada desert. And for those not satisfied with these small-town pleasures, the neon of Las Vegas beckoned just an hour or so down the highway.

But just as importantly, the work itself was deeply satisfying. After the slide rules and the geological charts were put away, there still remained some of that old childlike pleasure in watching things go boom. Wendell Weart: “I would go back in a tunnel and see what happened to these massive structures that we had put in there, and to see how it manhandled them and just wadded them up into balls. That was impressive.” Nor was the Nevada Test Site entirely an exercise in nuclear nihilism. While weapons development remained always the primary focus, most working there believed deeply in the peaceful potential for nuclear energy — even for nuclear explosions. One of the most extended and extensive test series conducted at the site was known as Operation Plowshare, a reference to “beating swords into plowshares” from the Book of Isaiah. Operation Plowshare eventually encompassed 27 separate explosions, stretching from 1961 to 1973. Its major focus was on nuclear explosions as means for carrying out grand earth-moving and digging operations, for the creation of trenches and canals among other things. (Such ideas formed the basis of the proposal Edward Teller bandied about during the Panama Canal controversy of the late 1970s to just dig another canal using hydrogen bombs.) Serious plans were mooted at one point to dig a whole new harbor at Cape Thompson in Alaska, more as a demonstration of the awesome potential of hydrogen bombs for such purposes than out of any practical necessity. Thankfully for the delicate oceanic ecosystem thereabouts, cooler heads prevailed in the end.

So, the people who worked at the site weren’t bad people. They were in fact almost uniformly good friends, good colleagues, good workers who were at the absolute tops of their various fields. Almost any one of them would have made a great, helpful neighbor. Nor, as Operation Plowshare and other projects attest, were they bereft of their own certain brand of idealism. If they sound heartlessly dismissive of the Downwinders’ claims and needlessly contemptuous of environmentalists who fret over the damage their work did and may still be doing, well, it would be hard for any of us to even consider the notion that the work to which we dedicated our lives — work which we thoroughly enjoyed, which made us feel good about ourselves, around which many of our happiest memories revolve — was misguided or downright foolish or may have even killed children, for God’s sake. I tend to see the people who worked at the site as embodying the best and the worst qualities of Americans in general, charging forward with optimism and industry and that great American can-do spirit — but perhaps not always thinking enough about just where they’re charging to.

The golden age of free-and-easy atomic testing at the Nevada Test Site ended at last on December 18, 1970. That was the day of Baneberry, a routine underground shot of just 10 kilotons. However, due to what the geophysicists involved claim was a perfect storm of factors, its containment model failed comprehensively. A huge cloud of highly radioactive particles burst to the surface and was blown directly over a mining encampment that was preparing the hole for another test nearby. By now the nature of radioactivity and its dangers was much better appreciated than it had been during the time of Operation Crossroads. All of the people at the encampment were put through extended, extensive decontamination procedures. Nevertheless, two heretofore healthy young men, an electrician and a security guard, died of leukemia within four years of the event. Their widows sued the government, resulting in another seemingly endless series of trials, feints, and legal maneuvers, culminating in yet another frustrating non-resolution in 1996: the government was found negligent and the plaintiffs awarded damages, but the deaths of the two men were paradoxically ruled not to have been a result of their radiation exposure. As many in the Downwinder community darkly noted at the time, a full admission of guilt in this case would have left the government open to a whole series of new lawsuits. Thus, they claimed, this strange splitting of the difference.

The more immediate consequence of Baneberry was a six-month moratorium on atomic testing at the Nevada Test Site while the accident was investigated and procedures were overhauled. When testing resumed, it did so in a much more controlled way, with containment calculations in particular required to go through an extended process of peer reviews and committee approvals. The Atomic Energy Commission also began for the first time to put pressure on the scientists and engineers to minimize the number of tests conducted by pooling resources and finding ways to get all the data they could out of each individual shot. The result was a slowdown from that high during the 1960s of about one shot per week to perhaps one or two per month. Old-timers grumbled about red tape and how the can-do spirit of the 1950s and 1960s had been lost, but, perhaps tellingly, there were no more Baneberrys. Of the roughly 350 shots at the Nevada Test Site after Baneberry, only 4 showed any detectable radiation leakage at all.

The site continued to operate right through the balance of the Cold War. The last bomb to be exploded there was also the last exploded to date by the United States: an anticlimactic little 5-kiloton shot on September 23, 1992. By this time, anti-nuclear activists had made the Nevada Test Site one of their major targets, and were a constant headache for everyone who worked there. Included among the ranks of those arrested for trespassing and disruption during the test site’s twilight years are Kris Kristofferson, Martin Sheen, Robert Blake, and Carl Sagan. Needless to say, the mood of the country and the public’s attitude toward nuclear weapons had changed considerably since those rah-rah days of atomic cap guns.

Since the mid-1990s the United States, along with Russia and the other established nuclear powers, has observed a long-lasting if non-binding tacit moratorium on all types of nuclear testing (a moratorium which unfortunately hasn’t been observed by new members of the nuclear club India, Pakistan, and North Korea). Stories of the days when mushroom clouds loomed over the Las Vegas Strip and the ground shook with the force of nuclear detonations are now something for long-time Nevada residents to share with their children or grandchildren. With its reason for existence in abeyance, the Nevada Test Site is in a state of largely deserted suspended animation today, Mercury a ghost town inhabited by only a few caretakers and esoteric researchers. One hopes that if Mercury should ever start to buzz with family life and commerce again it’s because someone has found some other, safer purpose for the desert landscape that surrounds it. In the meantime, the tunnels are still kept in readiness, just in case someone decides it’s time to start setting off the bombs again.

(The definitive resource on the history of the Nevada Test Site must be, now and likely forevermore, the University of Nevada at Las Vegas’s amazing Nevada Test Site Oral History Project. I could barely scratch the surface of the hundreds of lengthy interviews there when researching this article. And thanks to Duncan Stevens for his recommendation of Operation Crossroads by Jonathan M. Weisgall. I highly recommend the documentary The Atomic Cafe as a portrait of the era of atomic kitsch.)