In my last article I described some of the pioneering early work done in multimedia computing with the aid of the new technology of the laser disc. These folks were not the only ones excited by the laser disc’s potential. Plenty of others, at least some of them of a somewhat more, shall we say, mercenary disposition, considered how they could package these advancements into a form practical and inexpensive enough for home users. They dreamed of a new era of interactive video entertainment to supplement or even replace the old linear storytelling of traditional television. Tim Onosko described the dream in an article in the January 1982 issue of Creative Computing that reads like a scene from L.A. Noire:

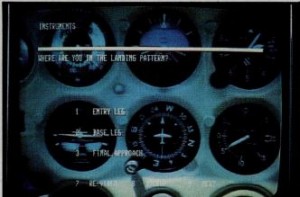

The scene is your living room. You’re watching a television program — let’s say it’s a cop show. A policeman is questioning a man suspected of committing a crime. The suspect answers in a barely audible tone, and his words come slowly. The policeman finishes his interrogation, then turns to the camera and asks you a question: should we believe him?

On a hand-held remote control, you press a button indicating that you doubt the suspect’s story. The cop consults you again, this time offering three possibilities.

Do you think the suspect was:

A) lying?

B) concealing important facts?

C) in shock and unable to communicate accurately?

The core of this idea was decades old even in 1982. Before she became the voice of Objectivism, Ayn Rand first attracted literary notice for her 1934 play Night of January 16th, a courtroom drama with a twist: members of the audience get to play the jury, deciding whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty. The ending of the play naturally depends on their choice. In 1967 the Czech director Radúz Činčera debuted his film Kinoautomat, in which the audience gets to vote on what happens next — and thus which scene is played next — nine times over the course of a viewing. On a less high-brow note, various cable operators during the 1970s experimented with what might be seen as the ancestors of American Idol, allowing the audience to vote their preferences via telephone. The main thing that distinguishes the scheme that Onosko describes above is that it places the individual, rather than a voting group, in control. In the dawning age of personal computing, that was no small distinction.

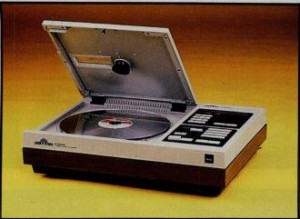

Still, interactive-video visionaries faced an uphill climb made even steeper by the very people who championed the laser disc as the next big thing in traditional home video. The legal team at MCA, co-developer of the laser disc, declared that their contracts with the Screen Actors Guild made it illegal to offer any sort of interactive features on their movie discs; they could only sell movies to be “viewed straight through.” Pioneer, the electronics brand with by far the biggest commercial presence in laser discs, didn’t even bother with excuses. They were simply uninterested in the various proposals from interested developers, not even deigning to reply to most. These big companies insisted on seeing the laser disc as a videocassette with better picture and sound, a difficult sale to make in light of the format’s other, very real disadvantages to the videocassette. Meanwhile its really revolutionary qualities, while not quite going unnoticed — Pioneer and others did make and sell industrial-grade players and the laser discs they played to the institutional projects I described in my last article as well as many more — were deemed of little ultimate significance in the consumer market.

Denied the industry sanction that might have made of the interactive laser disc a real force in consumer electronics, hobbyists and small developers did the best they could. A tiny company called Aurora Systems developed and sold an interface between an Apple II and the most popular of the early consumer-grade laser-disc players, the Pioneer VP-1000. Even so, those dreaming of a hobbyist-driven market for interactive laser-disc entertainment akin to that of the early general software market would be disappointed. A fundamental problem prevented it: even hobbyists with the equipment and the skill to shoot video sequences for their productions had no way to get it onto the read-only medium of the laser disc.

Admittedly, some went to great lengths to try to get around this. In that same January 1982 issue, which was given over almost entirely to the potential of the interactive laser disc and multimedia computing, Creative Computing published a fascinating experiment as a type-in program. Rollercoaster is a text adventure that requires not only an Apple II, a VP-1000, and the Aurora interface but also a laser disc of the 1977 movie of the same name. You, like George Segal in the film, are tasked with trying to stop a madman from blowing up a roller coaster. The game opens by playing an intro sequence from the laser disc interspersed with text. You see the madman planting the bomb, and see the airplane carrying you, a detective, arriving on the scene. Most of the locations you enter once the game proper begins are illustrated by a single frame judiciously chosen from the movie, and various actions are rewarded with a snippet of footage.

Rollercoaster, written by David Lubar with major design contributions from Creative Computing‘s publisher and editor David Ahl, is almost certainly the first computer game to incorporate what would come to be called the cut scene. It’s also the first to incorporate video footage from the real world, what would come to be given the tag of “full-motion video,” harbinger of a major if relatively short-lived game-industry craze of the 1990s. Still, its piggybacking on the film of another was legally problematic at best, and obviously inapplicable to a boxed-commercial-software industry. The fundamental blockage — that of lacking the resources to make original laser-disc content — remained. And then along came a Southern Californian named Rick Dyer, who made the deal that would bring interactive video to the masses.

Like so many others, Dyer had found his first encounter with Crowther and Woods’s Adventure a life-changing experience. Even as he built a lucrative career as a videogame programmer for Mattel and Coleco in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he dreamed of doing an adventure game in multimedia. Dissatisfied with the computer graphics available to him, he cast about far and wide for an alternative that would be more aesthetically pleasing. His first attempt was a sort of automated version of the Choose Your Own Adventure books that would soon be huge in children’s publishing. It consisted of a roll of tape upon which was printed text and pictures. As the player made choices using a keyboard, the controlling computer would shuttle the tape back and forth to expose the correct “page” for reading and viewing. Next he created a setup built around a computer-controlled slide projector, with a computer-controlled tape player used to play snippets of audio to accompany each slide. He also tried a complicated VCR setup, in which a videotape was laboriously rewound and fast-forwarded to find the next scenes needed by the game. When laser-disc players began to arrive in numbers, he felt he had the correct format at last. He started a company of his own, Advanced Micro Systems, and went to various toy companies with an idea he called The Fantasy Machine, a sort of interactive storybook for children. He found no takers. But then he met two partners just desperate enough to listen to his ideas.

Beginning in 1977, Cinematronics had developed and marketed quite a number of arcade games. Their games never entered the public consciousness in the way of an Asteroids or Pac-Man, but they did well enough, and are fondly remembered by arcade aficionados today. By 1982, however, the hits had stopped coming and the company’s vector-graphics technology had begun to look increasingly dated. Overextended and poorly managed like so many companies in this young and crazy industry, they ended up in bankruptcy, needing a hit game to convince the court not to liquidate them entirely. They found what looked like their best shot at such a thing in an unlikely place: in Dyer, who proposed adopting his interactive children’s storybook into an arcade experience. With little else on the horizon, they decided to roll the dice on Dyer’s scheme. Inside the arcade machine’s cabinet would be a very simple computer board, built around the tried-and-true Z80 processor, connected to a Pioneer laser-disc player. Dyer had found 5000 industrial-grade models of the latter languishing in a warehouse in Los Angeles, victims of the somewhat underwhelming reception of the laser disc in general. Pioneer was willing to sell them cheap — a critical consideration for a shoestring operation like this one.

With the hardware side in place, Dyer now needed someone to make the video footage his software would control. He had, in other words, come to the crux of the problem with computer-controlled video. Dyer, however, had an advantage: he lived on the doorstep of Hollywood. He was able to find just the person he needed in Don Bluth.

Bluth was a skilled animator who must have felt he had been born at the wrong time. He got his dream job at Disney in 1971, arriving just in time for the era that would go down as the nadir of Disney’s long history in animated film. Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men were now indeed getting old, and Walt himself was gone, leaving the studio without a strong leader. The result was almost two decades of critical and commercial underachievers, the sole exception being The Rescuers (1977), for which the eight remaining Old Men roused themselves to recapture the old spirit one last time. Bluth also got to work on that film, but otherwise his assignments were disheartening. Yet his options outside Disney were also limited at best. In this era the Saturday-morning cartoons were king. Bluth, a classicist by training and temperament, loathed the make’em-quick-and-cheap-and-sell-the-toys ethos of that world. (“There are two kinds of animation: the Bambi and Pinocchio classical style, and the Saturday-morning-cartoon type. I’d rather sell shoes than do the latter.”) When he left Disney at last in 1979 it was to form his own studio, Don Bluth Productions, to make the kind of big, lush animated features that didn’t seem to interest Disney anymore.

Most would say he delivered with 1982’s The Secret of NIMH, the first film that was fully his. But while the critics raved the public stayed away. Bluth blamed the film’s failure on his distributors MGM/UA, who failed to get it into enough theaters and promoted it only halfheartedly; MGM/UA would probably say that an old-fashioned, animated feature like NIMH was simply passé in the year of E.T., Star Trek II, and Tron. To add to Bluth’s woes, a major strike hit the animation industry just as he was hoping to begin production on a second film. He managed to cut a private deal with the union, but as he did so his financial backers lost faith and pulled their support for the new movie. With no obvious reason to continue to exist, Don Bluth Productions, like Cinematronics, faced bankruptcy and liquidation. And then, like Cinematronics, they got a call from Rick Dyer.

With little money of his own and with his partner literally bankrupt, Dyer couldn’t offer Bluth much beyond a one-third stake in whatever money the doubtful venture might eventually earn. Still, Bluth jumped on the proposal as “a dinghy to a sinking ship.” He scraped together a $300,000 loan, enough to prepare about five minutes of footage for a prototype system that the three partners, who now called themselves Starcom, could show to potential investors. The windfall came when Coleco, a Johnny-come-lately suddenly pushing hard to build a presence in home videogames, offered a cool $1 million for the right to make a home version of the game. Starcom wasn’t quite sure how Coleco was going to manage that, but they were thrilled to take their money. It was enough to let Bluth and company finish the 22 minutes of animated footage found in the final game, albeit barely; with no money to hire voice actors, for instance, the animators and their colleagues around the office simply did the voices themselves. (Editor Dan Molina, who voiced hapless hero Dirk the Daring, seems to have been channeling Scooby-Doo…)

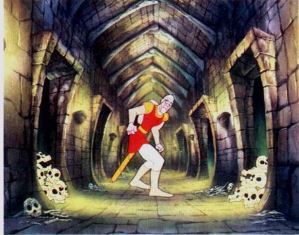

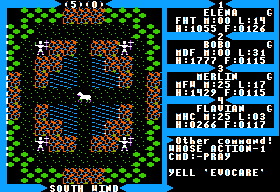

The decision to make The Fantasy Machine into an arcade game necessitated a radical retooling of Dyer’s original vision. Such a slow-paced exercise in interactive storytelling was obviously not going to fit in the frenetic world of the arcade, where owners expected games that were over in a few minutes and ready to accept the next quarter. The Fantasy Machine therefore became Dragon’s Lair, with the story stripped down to the very basics. You guide Dirk the Daring, a courageous but awkward hero in the tradition of Wart from The Sword in the Stone. Dirk loves Daphne, a shapely but empty-headed feminist’s nightmare modeled from old Playboy centerfolds. (Bluth: “Daphne’s elevator didn’t go all the way to the top floor, but she served a purpose.”) Daphne has been kidnapped by the evil wizard Mordorc and his pet dragon — horrid pun coming! — Singe. The game comes down to escaping all of the monsters, traps, and other obstacles in Mordorc’s castle until you arrive in the inner sanctum at last for the final showdown.

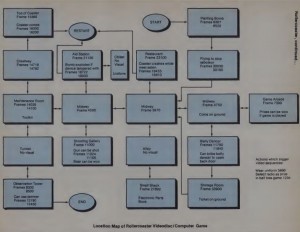

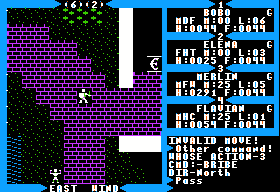

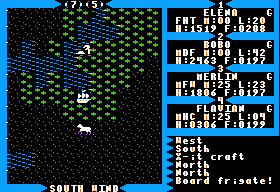

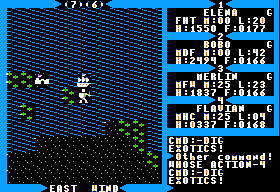

Menus asking what to do next were replaced by action sequences which require you to make the right movement with the joystick or hit the fire button to strike with the hero’s sword at the right instant as the video plays; failure means the loss of one of your three lives. At first the team tried to preserve some semblance of you actually guiding the story by placing, say, several doors in a room, each leading to a different scene. In time, however, even that fell away, as all meaningful choices were replaced by what the development team called a “threat/resolve” model. The game as released plays its 30 or so scenes in a randomized order to keep you from getting bored — or too comfortable, thus extending your time at the machine. In each, complete success or complete failure at executing the necessary arbitrary movements in the proper time windows are the only options. You either survive, in which case that scene is checked off your to-do list, or you die, in which case you lose a life, one of the silly death animations which make up a huge chunk of the total content on the laser disc plays, and the scene is shuffled back into the deck.

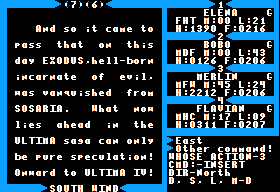

Let’s take a look at one of these scenes in action. The clip below shows one of the longest scenes in the game, running almost a full minute; many others are over in a scant ten seconds or less. After you (unavoidably) fall into the conveniently placed boat, you have to make thirteen movements with the joystick at the right instants. If you flub any one of these, the scene is immediately interrupted for a separate death sequence.

Lengthy as it is, this is actually one of the easier scenes in the game. The flashes in the oncoming tunnels give some clear visual indication of what you need to do, and most of the necessary actions are fairly intuitive. You may only need to die three or four times here to get the sequence straight. Most scenes are not so forgiving. It’s never obvious just when you should be trying to control Dirk and when you should just be watching; nor is it always clear which move is the correct one, or just when it needs to be executed. You can learn only through trial and error. Back in the day, you were paying 50¢ for every three lives whilst doing so; as a technological showcase the game was priced at twice the normal going rate. If we define a good game as one that gives you lots of interesting choices, Dragon’s Lair must be the worst game ever. As John Cawley noted in his book about Don Bluth, it’s more of a maze than a game; the smartest players were those who just watched other people play for hours while noting the correct moves, to be used to hopefully run through the whole thing in one go when they finally felt ready. I like the description at Dave’s Arcade best: “[Dragon’s Lair] is a hybrid of an animated movie and a Choose Your Own Adventure book…except the book is ripped from your hands and thrown across the room every time you fail to turn the page fast enough.” And yet, punishing as the game is while you learn the moves, it becomes trivial once you’ve accomplished that; within weeks of its release every arcade in America had that one annoying kid who had mastered it and used his skill to extend his time at the machine while frustrated arcade owners gnashed their teeth. Thus the game manages the neat trick of being too difficult and too easy at the same time.

None of which prevented it from turning into an absolute sensation when it arrived in arcades in the summer of 1983, and not only amongst the usual arcade rats. Thanks in some degree to Don Bluth, whose background as a traditional animator seemed to somehow legitimize Dragon’s Lair in their eyes, the mainstream media and the Hollywood establishment took to it with gusto. It got a feature spot on Entertainment Tonight, feature articles in The Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety, front-page coverage in a hundred newspapers. Ricky on Silver Spoons got his own personal Dragon’s Lair machine to play on as part of the show’s fantasy of living the good life, teenage style. The New York Post called it “a quantum jump into a whole new art form of the arcade.” Many people who had resisted the lure of the arcades during the days of Space Invaders and Pac-Man now came in at last to have a look and give it a go. Cinematronics couldn’t make enough machines to meet demand. Those arcades that managed to secure one sometimes had to snake velvet ropes around the premises for the line of people waiting to play. Some wired up additional monitors and mounted them high above the machine so the people in line could watch the current player’s exploits. One allegedly installed bleachers for the pure spectators. Most machines earned back their $4000 purchase price within a week or so, while also boosting earnings from all of the other, older machines around them that people played when they got bored of waiting for Dragon’s Lair.

The craze isn’t difficult to understand. Cursory observation — about all the average non-gaming beat reporter was likely to give it — can make it seem that the player is really controlling Dirk, really guiding him through a lushly animated, interactive cartoon. Seen in this light, and when compared to the flickering sprites and electronic bleeting of the other machines in the arcade, Dragon’s Lair could seem like an artifact beamed in from twenty years in the future. The audiovisual leap from old to new was so extreme as to be almost unfathomable, making Rick Dyer and Don Bluth look like technical sorcerers with access to secrets denied to the rest of the world. It felt like movies would have if they had leaped from The Jazz Singer to Star Wars in a year.

Pundits within the industry, meanwhile, had their own strong motivations to see Dragon’s Lair and the “laser-disc revolution” it allegedly harbingered in the best possible light. What had begun as a worrisome lack of continued growth in the arcade and home-game-console industries during the second half of 1982 had by that summer of 1983 become a clear, undeniable downturn that was looking more and more like it was about to become a free fall. It appeared that all of those who had snorted dismissively about the videogame “fad” might just have been right. And so, just as Don Bluth saw Dragon’s Lair as the dinghy that could save his company and his career in animation, arcade owners and game makers saw Dragon’s Lair as the dinghy that could save their industry. And for a while that really did seem possible. While the bottom dropped out of the home videogame market, Dragon’s Lair kept the arcades above water. (One arcade owner made a comment about Dragon’s Lair‘s popularity that could be read as ominous as easily as ecstatic: “There is no number two. It’s just taken over.”) People in the industry convinced themselves that 1984 would bring a wave of other, even better laser-disc games and the high times would well and truly be here again. John Cook, writer for an industry magazine, gushed that “by this time next year a new videogame without a laser-disc player will be as rare as a silent movie in 1929.”

In reality the second half of 1983, when Dragon’s Lair stood alone, was as good as it got for laser-disc games. Cook’s predicted avalanche of new games did hit with the new year, but they were uniformly uninspiring. They fell into two general categories: those that aped Dragon’s Lair‘s “interactive cartoon” approach with all of its associated limitations and those that used laser-disc video strictly as eye candy, displaying it behind and between levels of a more conventional game. In addition to their lack of depth, virtually all of these games also lacked the one saving grace of Dragon’s Lair: the skilled animators at Don Bluth Productions. Some of them did the best they could with the artists they could find; many grabbed their footage from cartoons or even feature films (Astron Belt, a game which actually predates Dragon’s Lair in its original Japanese release, used footage from the recent Star Trek II amongst other sources); all of them looked shabby in comparison to Bluth’s work. None did very well, and the industry as a whole settled back into the decline that Dragon’s Lair had briefly arrested.

Even Dyer and Bluth’s followup to Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace, despite having a more coherent, linear plot progression and giving the player at least a modicum of more control over its direction, failed to recapture the old magic. Players of Dragon’s Lair had fallen into two groups: the casually curious, who lost a couple of dollars before they even figured out what was happening on the screen or what they were supposed to be doing and moved on with a shrug; and the committed, who doggedly worked out the moves and battled their way to the end. With the novelty of the cartoon graphics now gone, neither group showed much interest in repeating the experience. As for the arcade industry: it would eventually stabilize and even recover somewhat, but those heady days circa 1981 would never return.

Even at its peak Dragon’s Lair never quite paid off for the folks who made it the way the hype might have made you think it did. Their lack of financial resources and the bankruptcy courts who had to approve Cinematronics’s every move kept them from fully capitalizing on the early publicity. They eventually ran out of the surplus, discontinued laser-disc players that Dyer had found, and had a terrible time getting new ones out of Pioneer. Cinematronics did manage to produce over 10,000 units over Dragon’s Lair‘s brief production run, a very impressive figure in a slumping arcade industry, but could probably have sold several times that if they could only have made them while the craze lasted. On the other hand, the game’s scarcity doubtlessly added to its mystique, and allowed Cinematronics to sell each unit for $4000, easily twice the industry’s going rate. Less ambiguously damaging were the technical faults that started to crop up after a few months. Dragon’s Lair worked its laser-disc player hard, sending the laser careening all over the disc for ten or twelve hours per day of constant use. Meanwhile the machine that housed it was getting constantly kicked, slapped, and jostled by angry or jubilant players (more of the former, one suspects, given the nature of the game). Pioneer had never planned for such conditions. The players started to fail in relatively short order, leaving Cinematronics scrambling to replace them, at considerable expense in money and in the precious new laser-disc players they had to use as replacements, for angry arcade owners who had just lost their cash cow.

The partners, like the industry as a whole, mistook player infatuation for commitment. Space Ace, which cost twice as much as Dragon’s Lair to make, did a bare fraction of the business. Development of a third game, Dragon’s Lair II, was halted in March of 1984. It was hoped that this would just be a temporary delay, to let the laser-disc scene shake itself out a bit and the substandard Dragon’s Lair knock-offs fade away. But by July Cinematronics couldn’t sell the Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace games that were now clogging their warehouse. Production had finally ramped up just in time for demand to cease. The world had moved on; Dragon’s Lair II was cancelled. The people who had planned to make it had no choice but to move on as well, although not without accusations and threats amongst the partners as everyone blamed everyone else for what had happened.

Cinematronics straggled on in the diminished arcade industry for more years than anyone might have expected before finally being acquired by another arcade survivor: WMS Industries, the company that had once been Williams Electronics of Defender fame.

Rick Dyer renamed his company RDI Video Systems to continue to pursue his original dream of The Fantasy Machine. He put together a laser-disc entertainment system for the home called Halcyon, or just Hal for short, a deliberate play on the computer HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey; apparently he judged that people thinking of inviting Hal into their living rooms wouldn’t think too much about HAL’s running rather messily amok in the film.

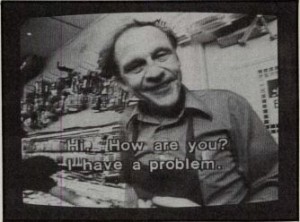

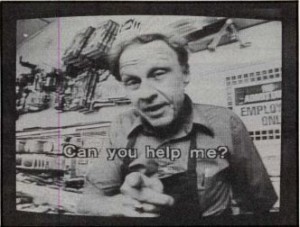

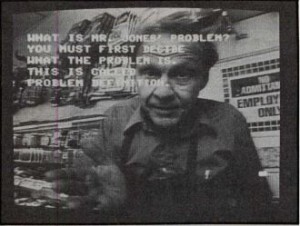

Hal talked to you, and, if he was in a good mood, accepted a limited number of voice commands back in return. This feature was enough evidence for RDI to declare that he was “artificially intelligent,” again without seeming to think about where HAL’s AI got the poor Discovery crew in the movie. Dyer and one of his partners appeared with Hal on Computer Chronicles, giving what has to be one of the most uncomfortable product demonstrations ever. Hal refuses to understand host Stewart Cheifet when he says the simple word “one,” to the point that Cheifet finally just gives up and takes option two instead. Meanwhile co-host Gary Kildall, no slouch in matters of computer science, presses Dyer and his associate relentlessly to abandon their patently silly AI claim; they just cling to it all the tighter.

Dyer hoped to release a whole line of interactive laser discs for Halcyon, but only three were ever completed: a couple of football games that use real NFL footage, and Thayer’s Quest, a menu-driven interactive story that hews very close to Dyer’s original plans for the game that became Dragon’s Lair.

Halcyon as a whole is an amazing, bizarre, visionary, kooky creation years ahead of its practical time. As the coup de grâce, RDI planned to sell it for a staggering $2200. It’s unclear whether any were actually sold on the open market before Dyer’s investors pulled the plug; if so, the numbers were truly minuscule. After Halcyon’s failure Dyer continued intermittently to work with interactive narratives, surfacing again in the mid-1990s with two adventure games, Kingdom: The Far Reaches and Kingdom II: Shadoan.

Don Bluth never had any real passion for videogames; it’s unfortunate that Dragon’s Lair has gone down in history as a Don Bluth creation, when in reality it was very much Rick Dyer’s vision. Even at the height of the game’s success Bluth always talked about it as a means to an end, a way to expose the arcade generation to the pleasures of classical animation rather than as a new type of entertainment in its own right. Short-lived as its success was, Dragon’s Lair served its purpose for Bluth. It did indeed become the dinghy that kept him afloat in the world of commercial animation until the opportunity to do another feature came along. Bluth found a backer in Steven Spielberg, whose Amblin Entertainment funded and released Bluth’s An American Tail in 1986. That film, along with the likes of The Brave Little Toaster and Who Framed Roger Rabbit, marked the beginning of a renaissance for animation on the big screen, paving the way for Pixar and a rejuvenated Disney to return the big-budget animated feature to the yearly blockbuster rolls in the 1990s. But another, more direct legacy of Dragon’s Lair probably didn’t thrill Bluth quite as much: the game was adapted into exactly the kind of knock-off Saturday-morning cartoon he loathed. Unfortunately for ABC, it debuted only in the fall of 1984, by which time the kids they were trying to reach had moved on long ago. It lasted for only one season of 13 episodes.

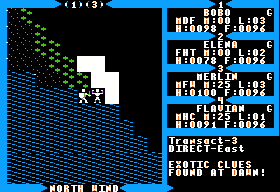

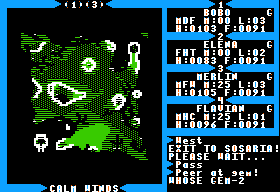

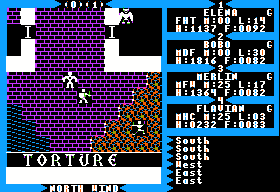

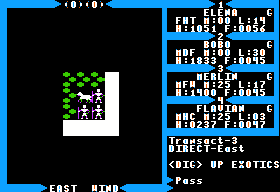

Coleco also saw little return for their investment in the Dragon’s Lair intellectual property. They had schemed on introducing a laser-disc player for their ColecoVision console and/or their ill-fated Adam home computer, but soon realized — shades of the $2200 Halcyon — it would just be too expensive to be practical. Instead they funded a completely new game for the Adam inspired by scenes from the original. It didn’t look as nice, but was probably more fun in the long run. That game turned out to be just the first — and arguably one of the best — of a long, confusing stream of games that have carried the Dragon’s Lair name since. When Readysoft released a version for the Amiga in late 1988 it was rightly seen as a landmark. As the first version that looked reasonably close to the laser-disc original, it marked just how far computer graphics had come in five years; soon we would be in the era of Pixar, when computers are used to create feature cartoons. But not all things change — the gameplay remained as simplistic as ever. Today Digital Leisure sells Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace, and Dragon’s Lair II, completed at last, in versions playable on anything from your Blu-Ray player to your iPhone. And yes, it’s still the same exercise in rote memorization it’s always been, with a few optional kindnesses to make the experience a bit less painful. Dragon’s Lair must be the most long-lived bad game in the history of the industry. Such is the power of nostalgia.

Dragon’s Lair makes an interesting study today not just as an historical curiosity or an example of style over substance, although it is both of those things. In addition to being one more crazy, unexpected offshoot of the original Adventure, that urtext of an industry, it’s an important early way station in gaming’s long relationship with movies; indeed, I believe it’s the first game to give itself the fraught title of “interactive movie.” The lesson that may seem obvious after playing Dragon’s Lair a few times is one that the industry would learn only slowly and painfully: non-interactive video is a problematic fit with an interactive medium, a subject we’ll undoubtedly explore in depth around here if we ever make it to the era of the lost and lamented (?) full-motion video games of the 1990s.

But for now let’s not judge Dragon’s Lair too harshly. It may not be much of a game, but, like so much of what I write about on this blog, it’s a great example of stretching available technology just as far as it will go and creating something kind of amazing in its time and place. For that golden six months in 1983, at least, that was more than enough. The impression it made on hearts and minds in that short span of time has fueled thirty years of nostalgia. Not bad for a 22-minute cartoon.

(As mentioned in the article, you can still buy various incarnations of Dragon’s Lair and associated games from Digital Leisure. You can also use some of these products as a key to let you play the games in their original form using the Daphne emulator. See that project’s website for more information.

Primary sources used for this article included articles in the January 1982 Creative Computing, the November 1983, January 1984, and January 1985 Electronic Games, and the April 1984 Enter. Online sources included The Dot Eaters and The Dragon’s Lair Project. Finally, John Cawley’s book The Animated Films of Don Bluth was indispensable.)