A quick note on terminology before we get started: “CD-ROM” can be used to refer either to the use of CDs as a data-storage format for computers in general or to the Microsoft-sponsored specification for same. I’ll be using the term largely in the former sense in the introduction to this article, in the latter after something called “CD-I” enters the picture. I hope the point of transition won’t be too hard to identify, but my apologies if this leads to any confusion. Sometimes this language of ours is a very inexact thing.

In the first week of March 1986, much of the computer industry converged on Seattle for the first annual Microsoft CD-ROM Conference. Microsoft had anticipated about 500 to 600 attendees to the four-day event. Instead more than 1000 showed up, forcing the organizers to reject many of them at the door of a conference center that by law could only accommodate 800 people. Between the presentations on CD-ROM’s bright future, the attendees wandered through an exhibit hall showcasing the format’s capabilities. The hit of the hall was what was about to become the first CD-ROM product ever to be made available for sale to the public, consisting of the text of all 21 volumes of the Grolier Academic Encyclopedia, some 200 MB in all, on a single disc. It was to be published by KnowledgeSet, a spinoff of Digital Research. Digital’s founder Gary Kildall, apparently forgiving Bill Gates his earlier trespasses in snookering a vital IBM contract out from under his nose, gave the conference’s keynote address.

Kildall’s willingness to forgive and forget in light of the bright optical-storage future that stood before the computer industry seemed very much in harmony with the mood of the conference as a whole. Sentiments often verged on the utopian, with talk of a new “paperless society” abounding, a revolution to rival that of Gutenberg. “The compact disc represents a major discontinuity in the cost of producing and distributing information,” said one Ed Schmid of DEC. “You have to go back to the invention of movable type and the printing press to find something equivalent.” The enthusiasm was so intense and the good vibes among the participants — many of them, like Gates and Kildall, normally the bitterest of enemies — so marked that some came to call the conference “the computer industry’s Woodstock.” If the attendees couldn’t quite smell peace and love in the air, they certainly could smell potential and profit.

All the excitement came down to a single almost unbelievable number: the 650 MB of storage offered by every tiny, inexpensive-to-manufacture compact disc. It’s very, very difficult to fully convey in our current world of gigabytes and terabytes just how inconceivably huge a figure 650 MB actually was in 1986, a time when a 40 MB hard drive was a cavernous, how-can-I-ever-possibly-fill-this-thing luxury found on only the most high-end computers. For developers who had been used to making their projects fit onto floppy disks boasting less than 1 MB of space, the idea of CD-ROM sounded like winning the lottery several times over. You could put an entire 21-volume encyclopedia on one of the things, for Pete’s sake, and still have more than two-thirds of the space left over! Suddenly one of the most nail-biting constraints against which they had always labored would be… well, not so much eased as simply erased. After all, how could anything possibly fill 650 MB?

And just in case that wasn’t enough great news, there was also the fact that the CD was a read-only format. If the industry as a whole moved to CD-ROM as its format of choice, the whole piracy problem, which organizations like the Software Publishers Association ardently believed was costing it billions every year, would dry up and blow away like a dandelion in the fall. Small wonder that the mood at the conference sometimes approached evangelistic fervor. Microsoft, as swept away with it all as anyone, published a collection of the papers that were presented there under the very non-businesslike, non-Microsoft-like title of CD-ROM: The New Papyrus. The format just seemed to demand a touch of rhapsodic poetry.

But the rhapsody wasn’t destined to last very long. The promised land of a software industry built around the effectively unlimited storage capacity of the compact disc would prove infuriatingly difficult to reach; the process of doing so would stretch over the better part of a decade, by the end of which time the promised land wouldn’t seem quite so promising anymore. Throughout that stretch, CD-ROM was always coming in a year or two, always the next big thing right there on the horizon that never quite arrived. This situation, so antithetical to the usual propulsive pace of computer technology, was brought about partly by limitations of the format itself which were all too easy to overlook amid the optimism of that first conference, and partly by a unique combination of external factors that sometimes almost seemed to conspire, perfect-storm-like, to keep CD-ROM out of the hands of consumers.

The compact disc was developed as a format for music by a partnership of the Dutch electronics giant Philips and the Japanese Sony during the late 1970s. Unlike the earlier analog laser-disc format for the storage of video, itself a joint project of Philips and the American media conglomerate MCA, the CD stored information digitally, as long strings of ones and zeros to be passed through digital-to-analog converters and thus turned into rich stereo sound. Philips and Sony published the final specifications for the music CD in 1980, opening up to others who wished to license the technology what would become known as the “Red Book” standard after the color of the binder in which it was described. The first consumer-oriented CD players began to appear in Japan in 1982, in the rest of the world the following year. Confined at first to the high-end audiophile market, by the time of that first Microsoft CD-ROM Conference in 1986 the CD was already well on its way to overtaking the record album and, eventually, the cassette tape to become the most common format for music consumption all over the world.

There were good reasons for the CD’s soaring popularity. Not only did CDs sound better than at least all but the most expensive audiophile turntables, with a complete absence of hiss or surface noise, but, given that nothing actually touched the surface of a disc when it was being played, they could effectively last forever, no matter how many times you listened to them; “Perfect sound forever!” ran the tagline of an early CD advertising campaign. Then there was the way you could find any song you liked on a CD just by tapping a few buttons, as opposed to trying to drop a stylus on a record at just the right point or rewind and fast-forward a cassette to just the right spot. And then there was the way that CDs could be carried around and stored so much more easily than a record album, plus the way they could hold up to 75 minutes worth of music, enough to pack many double vinyl albums onto a single CD. Throw in the lack of a need to change sides to listen to a full album, and seldom has a new media format appeared that is so clearly better than the existing formats in almost all respects.

It didn’t take long for the computer industry to come to see the CD format, envisioned originally strictly as a music medium, as a natural one to extend to other types of data storage. Where the rubber met the road — or the laser met the platter — a CD player was just a mechanism for reading bits off the surface of the disc and sending them on to some other circuitry that knew what to do with them. This circuitry could just as easily be part of a computer as a stereo system.

Such a sanguine view was perhaps a bit overly reductionist. When one started really delving into the practicalities of the CD as a format for data storage, one found a number of limitations, almost all of them drawn directly from the technology’s original purpose as a music-delivery solution. For one thing, CD drives were only capable of reading data off a disc at a rate of 153.6 K per second, this figure corresponding not coincidentally to the speed required to stream standard CD sound for real-time playback. [1]The data on a music CD is actually read at a speed of approximately 172.3 K per second. The first CD-ROM drives had an effective reading speed that was slightly slower due to the need for additional error-correcting checksums in the raw data. Such a throughput was considered pretty good but hardly breathtaking by mid-1980s hard-disk standards; an average 10 MB hard drive of the period might have a transfer rate of about 96 K per second, although high-performance drives could triple or even quadruple that figure.

More problematic was a CD drive’s atrocious seek speed — i.e., the speed at which files could be located for reading on a disc. An average 10 MB hard disk of 1986 had a typical seek time of about 100 milliseconds, a worst-case-scenario maximum of about 200 — although, again, high-performance models could improve on those figures by a factor of four. A CD drive, by contrast, had a typical seek time of 500 milliseconds, a maximum of 1000 — one full second. The designers of the music CD hadn’t been particularly concerned by the issue, for a music-CD player would spend the vast majority of its time reading linear streams of sound data. On those occasions when the user did request a certain track found deeper on the disc, even a full second spent by the drive in seeking her favorite song would hardly be noticed unduly, especially in comparison to the pain of trying to find something on a cassette or a record album. For storage of computer data, however, the slow seek speed gave far more cause for concern.

The Laser Magnetic Storage LaserDrive is typical of the oddball formats that proliferated during the early years of optical data storage. It could hold 1 GB on each side of a double-sided disc. Unfortunately, each disc cost hundreds of dollars, the unit itself thousands.

Given these issues of performance, which promised only to get more marked in comparison to hard drives as the latter continued to get faster, one might well ask why the industry was so determined to adapt the music CD specifically to data storage rather than using Philips and Sony’s work as a springboard to another optical format with affordances more suitable to the role. In fact, any number of companies did choose the latter course, developing optical formats in various configurations and capacities, many even offering the ability to write to as well as read from the disc. (Such units were called “WORM” drives, for “Write Once Read Many”; data, in other words, could be written to their discs, but not erased or rewritten thereafter.) But, being manufactured in minuscule quantities as essentially bespoke items, all such efforts were doomed to be extremely expensive.

The CD, on the other hand, had the advantage of an existing infrastructure dedicated to stamping out the little silver discs and filling them with data. At the moment, that data consisted almost exclusively of encoded music, but the process of making the discs didn’t care a whit what the ones and zeros being burned into them actually represented. CD-ROM would allow the computer industry to piggy-back on an extant, mature technology that was already nearing ubiquity. That was a huge advantage when set against the cost of developing a new format from scratch and setting up a similar infrastructure to turn it out in bulk — not to mention the challenge of getting the chaotic, hyper-competitive computer industry to agree on another format in the first place. For all these reasons, there was surprisingly little debate on whether adapting the music CD to the purpose of data storage was really the best way to go. For better or for worse, the industry hitched its wagon to the CD; its infelicities as a general-purpose data-storage solution would just have to be worked around.

One of the first problems to be confronted was the issue of a logical file format for CD-ROM. The physical layout of the bits on a data CD was largely dictated by the design of the platters themselves and the machinery used to burn data into them. Yet none of that existing infrastructure had anything to say about how a filesystem appropriate for use with a computer should work within that physical layout. Microsoft, understanding that a certain degree of inter-operability was a valuable thing to have even among the otherwise rival platforms that might wind up embracing CD-ROM, pushed early for a standardized logical format. As a preliminary step on the road to that landmark first CD-ROM Conference, they brought together a more intimate group of eleven other industry leaders at the High Sierra Resort and Casino in Lake Tahoe in November of 1985 to hash out a specification. Among those present were Philips, Sony, Apple, and DEC; notably absent was IBM, a clear sign of Microsoft’s growing determination to step out of the shadow of Big Blue and start dictating the direction of the industry in their own right. The so-called “High Sierra” format would be officially published in finalized form in May of 1986.

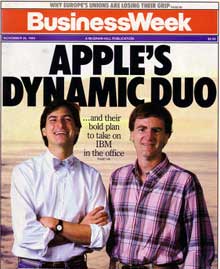

In the run-up to the first Microsoft CD-ROM Conference, then, everything seemed to be coming together nicely. CD-ROM had its problems, but virtually everyone agreed that it was a tremendously exciting development. For their part, Microsoft, driven by a Bill Gates who was personally passionate about the format and keenly aware that his company, the purveyor of clunky old MS-DOS, needed for reasons of public relations if nothing else a cutting-edge project to rival any of Apple’s, had established themselves as the driving force behind the nascent optical revolution. And then, just five days before the conference was scheduled to convene — timing that struck very few as accidental — Philips injected a seething ball of chaos into the system via something called CD-I.

CD-I was a different, competing file format for CD data storage. But CD-I was also much, much more. Excited by the success the music CD had enjoyed, Philips, with the tacit support of Sony, had decided to adapt the format into the all-singing, all-dancing, all-around future of home entertainment in the abstract. Philips would be making a CD-I box for the home, based on a minimalist operating system called OS-9 running on a Motorola 68000 processor. But this would be no typical home computer; the user would be able to control CD-I entirely using a VCR-style remote control. CD-I was envisioned as the interactive television of the future, a platform for not only conventional videogames but also lifestyle products of every description, from interactive astronomy lessons to the ultimate in exercise tapes. Philips certainly wasn’t short of ideas:

Think of owning an encyclopedia which presents chosen topics in several different ways. Watching a short audio/video sequence to gain a general background to the topic. Then choosing a word or subject for more in-depth study. Jumping to another topic without losing your place — and returning again after studying the related topic to proceed further. Or watching a cartoon film, concert, or opera with the interactive capabilities of CD-I added. Displaying the score, libretto, or text onscreen in a choice of languages. Or removing one singer or instrument to be able to sing along with the music.

Just as they had with the music CD, Philips would license the specifications to whoever else wanted to make gadgets of their own capable of playing the CD-I discs. They declared confidently that there would be as many CD-I players in the world as phonographs within a few years of the format’s debut, that “in the long run” CD-I “could be every bit as big as the CD-audio market.”

Already at the Microsoft CD-ROM Conference, Philips began aggressively courting developers in the existing computer-games industry to embrace CD-I. Plenty of them were more than happy to do so. Despite the optimism that dominated at the conference, it wasn’t clear how much priority Microsoft, who earned the vast majority of their money from business computing, would really give to more consumer-focused applications of CD-ROM like gaming. Philips, on the other hand, was a giant of consumer electronics. While they paid due lip service to applications of CD-I in areas like corporate training, it was always clear that it would be first and foremost a technology for the living room, one that comprehensively addressed what most believed was the biggest factor limiting the market for conventional computer games: that the machines that ran them were just too fiddly to operate. At the time that CD-I was first announced, the videogame console was almost universally regarded as a dead fad; the machine that would so dramatically reverse that conventional wisdom, the Nintendo Entertainment System, was still an oddball upstart being sold in selected markets only. Thus many game makers saw CD-I as their only viable route out of the back bedroom and into the living room — into the mainstream of home entertainment.

So, when Philips spoke, the game developers listened. Many publishers, including big powerhouses like Activision as well as smaller boutique houses like the 68000 specialists Aegis Development, committed to CD-I projects during 1986, receiving in return a copy of the closely guarded “Green Book” that detailed the inner workings of the system. There was no small pressure to get in on the action quickly, for Philips was promising to ship the first finished CD-I units in time for the Christmas of 1987. Trip Hawkins of Electronic Arts made CD-I a particular priority, forming a whole new in-house development division for the platform. He’d been waiting for a true next-generation mainstream game machine for years. At first, he’d thought the Commodore Amiga would be that machine, but Commodore’s clueless marketing and the Amiga’s high price were making such an outcome look less and less likely. So now he was looking to CD-I, which promised graphics and sound as good as those of the Amiga, along with the all but infinite storage of the unpirateable CD format, and all in a tidy, inexpensive package designed for the living room. What wasn’t to like? He imagined Silicon Valley becoming “the New Hollywood,” imagined a game like Electronic Arts’s hit Starflight remade as a CD-I experience.

You could actually do it just like a real movie. You could hire a costume designer from the movie business, and create special-effects costumes for the aliens. Then you’d videotape scenes with the aliens, and have somebody do a soundtrack for the voices and for the text that they speak in the game.

Then you’d digitize all of that. You could fill up all the space on the disc with animated aliens and interesting sounds. You would also have a universe that’s a lot more interesting to look at. You might have an out-of-the-cockpit view, like Star Trek, with planets that look like planets — rotating, with detailed zooms and that sort of thing.

Such a futuristic vision seemed thoroughly justifiable based on Philips’s CD-I hype, which promised a rich multimedia environment combining CD-quality stereo sound with full-motion video, all at a time when just displaying a photo-realistic still image captured from life on a computer screen was considered an amazing feat. (Among extant personal computers, only the Amiga could manage it.) When developers began to dive into the Green Book, however, they found the reality of CD-I often sharply at odds with the hype. For instance, if you decided to take advantage of the CD-quality audio, you had to tie up the CD drive entirely to stream it, meaning you couldn’t use it to fetch pictures or video or anything else for this supposed rich multimedia environment.

Video playback became an even bigger sore spot that echoed back to those fundamental limitations that had been baked into the CD when it was regarded only as a medium for music delivery. A transfer rate of barely 150 K per second just wasn’t much to work with in terms of streaming video. Developers found themselves stymied by an infuriating Catch-22. If you tried to work with an uncompressed or only modestly compressed video format, you simply couldn’t read it off the disk fast enough to display it in real-time. Yet if you tried to use more advanced compression techniques, it became so expensive in terms of computation to decompress the data that the CD-I unit’s 68000 CPU couldn’t keep up. The best you could manage was to play video snippets that only filled a quarter of the screen — not a limitation that felt overly compatible with the idea of CD-I as the future of home entertainment in the abstract. It meant that a game like the old laser-disc-driven arcade favorite Dragon’s Lair, the very sort of thing people tended to think of first when you mentioned optical storage in the context of entertainment, would be impossible with CD-I. The developers who had signed contracts with Philips and committed major resources to CD-I could only soldier on and hope the technology would continue to evolve.

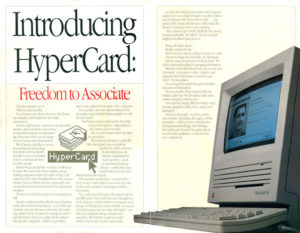

By 1987, then, the CD as a computer format had been split into two camps. While the games industry had embraced CD-I, the powers that were in business computing had jumped aboard the less ambitious, Microsoft-sponsored standard of CD-ROM, which solved issues like the problematic video playback of CD-I by the simple expediency of not having anything at all to say about them. Perhaps the most impressive of the very early CD-ROM products was the Microsoft Bookshelf, which combined Roget’s Thesaurus, The American Heritage Dictionary, The Chicago Manual of Style, The World Almanac and Book of Facts, and Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations alongside spelling and grammar checkers, a ZIP Code directory, and a collection of forms and form letters, all on a single disc — as fine a demonstration of the potential of the new format as could be imagined short of all that rich multimedia that Philips had promised. Microsoft proudly noted that Bookshelf was their largest single product ever in terms of the number of bits it contained and their smallest ever in physical size. Nevertheless, with most drives costing north of $1000 and products to use with them like Microsoft Bookshelf hundreds more, CD-ROM remained a pricey proposition found in vanishingly few homes — and for that matter not in all that many businesses either.

But at least actual products were available in CD-ROM format, which was more than could be said for CD-I. As 1986 turned into 1987, developers still hadn’t received any CD-I hardware at all, being forced to content themselves with printed specifications and examples of the system in action distributed on videotape by Philips. Particularly for a small company like Aegis, which had committed heavily to a game based on Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, for which they had recruited Jim Sachs of Defender of the Crown fame as illustrator, it was turning into a potentially dangerous situation.

The computer industry — even those parts of it now more committed to CD-I than CD-ROM — dutifully came together once again for the second Microsoft CD-ROM Conference in March of 1987. In contrast to the unusual Pacific Northwest sunshine of the previous conference, the weather this year seemed to match the more unsettled mood: three days of torrential downpour. It was a more skeptical and decidedly less Woodstock-like audience who filed into the auditorium one day for a presentation by no less unlikely a party than the venerable old American conglomerate General Electric. But in the course of that presentation, the old rapture came back in a hurry, culminating in a spontaneous standing ovation. What had so shocked and amazed the audience was the impossible made real: full-screen video running in real-time off a CD drive connected to what to all appearances was an ordinary IBM PC/AT computer. Digital Video Interactive, or DVI, had just made its dramatic debut.

DVI’s origins dated back to 1983, when engineer Larry Ryan of another old-school American company, RCA, had been working on ways to make the old analog laser-disc technology more interactive. Growing frustrated with the limitations he kept bumping against, he proposed to his bosses that RCA dump the laser disc from the equation entirely and embrace digital optical storage. They agreed, and a new project on those lines was begun in 1984. It was still ongoing two years later — just reaching the prototype stage, in fact — when General Electric acquired RCA.

DVI worked by throwing specialized hardware at the problem which Philips had been fruitlessly trying to solve via software alone. By using ultra-intensive compression techniques, it was possible to crunch video playing at a resolution of 256 X 240 — not an overwhelming resolution even by the standards of the day, but not that far below the practical resolution of a typical television set either — down to a size below 153.6 K per second of footage without losing too much quality. This fact was fairly well-known, not least to Philips. The bottleneck had always been the cost of decompressing the footage fast enough to get it onto the screen in real time. DVI attacked this problem via a hardware add-on that consisted principally of a pair of semi-autonomous custom chips designed just for the task of decompressing the video stream as quickly as possible. DVI effectively transformed the potential 75 minutes of sound that could be stored on a CD into 75 minutes of video.

Philosophically, the design bore similarities to the Amiga’s custom chips — similarities which became even more striking when you considered some of the other capabilities that came almost as accidental byproducts of the design. You could, for instance, overlay conventional graphics onto the streaming video by using the computer’s normal display circuitry in conjunction with DVI, just as you could use an Amiga to overlay titles and other graphics onto a “genlocked” feed from a VCR or other video source. But the difference with DVI was that it required no complicated external video source at all, just a CD in the computer’s CD drive. The potential for games was obvious.

In this demonstration of DVI’s potential, the user can explore an ancient Mayan archeological site that’s depicted using real-world video footage, while the icons used as controls are traditional computer graphics.

Still, DVI’s dramatic debut barely ended before the industry’s doubts began. It seemed clear enough that DVI was technically better than CD-I, at least in the hugely important area of video playback, but General Electric — hardly anyone’s idea of a nimble innovator — offered as yet no clear road map for the technology, no hint of what they really planned to do with it. Should game developers place their CD-I projects on hold to see if something better really was coming in the form of DVI, or should they charge full speed ahead and damn the torpedoes? Some did one, some did the other; some made halfhearted commitments to both technologies, some vacillated between them.

But worst of all was the effect that DVI had on Philips. They were thrown into a spin by that presentation from which they never really recovered. Fearful of getting their clock cleaned in the marketplace by a General Electric product based on DVI, Philips stopped CD-I in its tracks, demanding that a way be found to make it do full-screen video as well. From an original plan to ship the first finished CD-I units in time for Christmas 1987, the timetable slipped to promise the first prototypes for developers by January of 1988. Then that deadline also came and went, and all that developers had received were software emulators. Now the development prototypes were promised by summer 1988, finished units expected to ship in 1989. The delay notwithstanding, Philips still confidently predicted sales in “the tens of millions.” But then world domination was delayed again until 1990, then 1991.

Wanting CD-I to offer the best of everything, the project chased its own tail for years, trying to address every actual or potential innovation from every actual or potential rival. The game publishers who had jumped aboard with such enthusiasm in the early days were wracked with doubt upon the announcement of each successive delay. Should they jump off the merry-go-round now and cut their losses, or should they stay the course in the hope that CD-I finally would turn into the revolutionary product Philips had been promising for so long? To this day, you merely have to mention CD-I to even the most mild-mannered old games-industry insider to be greeted with a torrent of invective. Philips’s merry-go-round cost the industry huge. Some smaller developers who had trusted Philips enough to bet their very survival on CD-I paid the ultimate price. Aegis, for example, went out of business in 1990 with CD-I still vaporware.

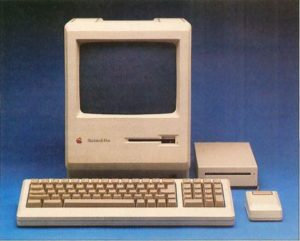

While CD-I chased its tail, General Electric, the unwitting instigators of all this chaos, tried to decide in their slow, bureaucratic way what to do with this DVI thing they’d inherited. Thus things were as unsettled as ever on the CD-I and DVI fronts when the third Microsoft CD-ROM Conference convened in March of 1988. The old plain-Jane CD-ROM format, however, seemed still to be advancing slowly but steadily. Certainly Microsoft appeared to be in fine fettle; harking back to the downpour that had greeted the previous year’s conference, they passed out oversized gold umbrellas to everyone — emblazoned, naturally, with the Microsoft logo in huge type. They could announce at their conference that the High Sierra logical format for CD-ROM had been accepted, with some modest modifications to support languages other than English, by the International Standards Organization as something that would henceforward be known as “ISO 9660.” (It remains the standard logical format for CD-ROM to this day.) Meanwhile Philips and Sony were about to begrudgingly codify the physical format for CD-ROM, extant already as a de facto standard for several years now, as the Yellow Book, latest addition to a library of binders that was turning into quite the rainbow. Apple, who had previously been resistant to CD-ROM, driven as it was by their arch-rival Microsoft, showed up with an official CD-ROM drive for a Macintosh or even an Apple II, albeit at a typically luxurious Apple price of $1200. Even IBM showed up for the conference this time, albeit with a single computer attached to a non-IBM CD-ROM drive and a carefully noncommittal official stance on all this optical evangelism.

As CD-ROM gathered momentum, the stories of DVI and CD-I alike were already beginning to peter out in anticlimax. After doing little with DVI for eighteen long months, General Electric finally sold it to Intel at the end of 1988, explaining that DVI just “didn’t mesh with [their] strategic plans.” Intel began shipping DVI setups to early adopters in 1989, but they cost a staggering $20,000 — a long, long way from a reasonable consumer price point. DVI continued to lurch along into the 1990s, but the price remained too high. Intel, possessed of no corporate tradition of marketing directly to consumers, often seemed little more motivated to turn DVI into a practical product than had been General Electric. Thus did the technology that had caused such a sensation and such disruption in 1987 gradually become yesterday’s news.

Ironically, we can lay the blame for the creeping irrelevancy of DVI directly at the feet of the work for which Intel was best known. As Gordon Moore — himself an Intel man — had predicted decades before, the overall throughput of Intel’s most powerful microprocessors continued to double every two years or so. This situation meant that the problem DVI addressed through all that specialized hardware — that of conventional general-purpose CPUs not having enough horsepower to decompress an ultra-compressed video stream fast enough — wasn’t long for this world. And meanwhile other engineers were attacking the problem from the other side, addressing the standard CD’s reading speed of just 153.6 K per second. They realized that by applying an integral multiplier to the timing of a CD drive’s circuitry, its reading (and seeking) speed could be increased correspondingly. Soon so-called “2X” drives began to appear, capable of reading data at well over 300 K per second, followed in time by “4X” drives, “8X” drives, and whatever unholy figure they’ve reached by today. These developments rendered all of the baroque circuitry of DVI pointless, a solution in search of a problem. Who needed all that complicated stuff?

CD-I’s end was even more protracted and ignominious. The absurd wait eventually got to be too much for even the most loyal CD-I developers. One by one, they dropped their projects. It marked a major tipping point when in 1989 Electronic Arts, the most enthusiastic of all the software publishers in the early days of CD-I, closed down the department they had formed to develop for the platform, writing off millions of dollars on the aborted venture. In another telling sign of the times, Greg Riker, the manager of that department, left Electronic Arts to work for Microsoft on CD-ROM.

When CD-I finally trickled onto store shelves just a few weeks shy of Christmas 1991, it was able to display full-screen video of a sort but only in 128 colors, and was accompanied by an underwhelming selection of slapdash games and lifestyle products, most funded by Philips themselves, that were a far cry from those halcyon expectations of 1986. CD-I sales disappointed — immediately, consistently, and comprehensively. Philips, nothing if not persistent, beat the dead horse for some seven years before giving up at last, having sold only 1 million units in total, many of them at fire-sale discounts.

In the end, the big beneficiary of the endless CD-I/DVI standoff was CD-ROM, the simple, commonsense format that had made its public debut well before either of them. By 1993 or so, you didn’t need anything special to play video off a CD at equivalent or better quality to that which had been so amazing in 1987; an up-to-date CPU combined with a 2X CD-ROM drive would do the job just fine. The Microsoft standard had won out. Funny how often that happened in the 1980s and 1990s, isn’t it?

Bill Gates’s reputation as a master Machiavellian being what it is, I’ve heard it suggested that the chaos and indecision which followed the public debut of DVI had been consciously engineered by him — that he had convinced a clueless General Electric to give that 1987 demonstration and later convinced Intel to keep DVI at least ostensibly alive and thus paralyzing Philips long enough for everyday PC hardware and vanilla CD-ROM to win the day, all the while knowing full well that DVI would never amount to anything. That sounds a little far-fetched to this writer, but who knows? Philips’s decision to announce CD-I five days before Microsoft’s CD-ROM Conference had clearly been a direct shot across Bill Gates’s bow, and such challenges did tend not to end well for the challenger. Anything else is, and must likely always remain, mere speculation.

(Sources: Amazing Computing of May 1986; Byte of May 1986, October 1986, April 1987, January 1989, May 1989, and December 1990; Commodore Magazine of November 1988; 68 Micro Journal of August/September 1989; Compute! of February 1987 and June 1988; Macworld of April 1988; ACE of September 1989, March 1990, and April 1990; The One of October 1988 and November 1988; Sierra On-Line’s newsletter of Autumn 1989; PC Magazine of April 29 1986; the premiere issue of AmigaWorld; episodes of the Computer Chronicles television series entitled “Optical Storage Devices,” “CD-ROMs,” and “Optical Storage”; the book CD-ROM: The New Papyrus from the Microsoft Press. Finally, my huge thanks to William Volk, late of Aegis and Mediagenic, for sharing his memories and impressions of the CD wars with me in an interview.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The data on a music CD is actually read at a speed of approximately 172.3 K per second. The first CD-ROM drives had an effective reading speed that was slightly slower due to the need for additional error-correcting checksums in the raw data. |

|---|