Steve Jobs’s unique sense of design and aesthetics has dominated every technology project he’s led following the Apple II — for better (the modern Macintosh, the iPhone, the iPod, the iPad) or worse (the Apple III) or somewhere in between (the original 1984 Macintosh, the NeXT workstations). The Apple II, though, was different. While Jobs’s stamp was all over it, so too was the stamp of another, very different personality: Steve Wozniak. The Apple II was a sort of dream machine, a product genuinely capable of being very different things to different people, for it unified Woz’s hackerish dedication to efficiency, openness, and possibility with Jobs’s gift for crafting elegant experiences for ordinary end users. The two visions it housed would soon begin to pull violently against one another, at Apple as in the computer industry as a whole, but for this moment in time, in this machine only, they found a perfect balance.

To call Jobs a mediocre engineer is probably giving him too much credit; the internals of the Apple II were all Woz. Steven Levy describes his motivation to build it:

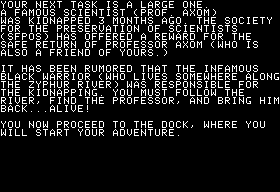

It was the fertile atmosphere of Homebrew that guided Steve Wozniak through the incubation of the Apple II. The exchange of information, the access to esoteric technical hints, the swirling creative energy, and the chance to blow everybody’s mind with a well-hacked design or program… these were the incentives which only increased the intense desire Steve Wozniak already had: to build the kind of computer he wanted to play with. Computing was the boundary of his desires; he was not haunted by visions of riches and fame, nor was he obsessed by dreams of a world of end users exposed to computers.

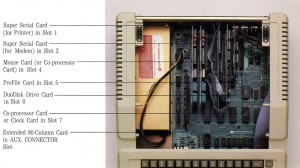

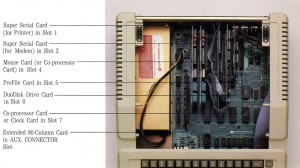

When you open an Apple II, you see a lot of slots and a lot of empty space.

All those slots were key to Woz’s vision of the machine as a hacker’s ultimate plaything; each was an invitation to extend it in some interesting way. Predictably, Jobs was nonplussed by Woz’s insistence on devoting all that space to theoretical future possibilities, as this did not jibe at all with his vision of the Apple II as a seamless piece of consumer electronics to be simply plugged in and used. Surely one or two slots is more than sufficient, he bargained. Normally Jobs, by far the more forceful personality of the two, inevitably won disputes like this — but this time Woz uncharacteristically held his ground and got his slots.

Lucky that he did, too. Within months hackers, third-party companies, and Apple itself began finding ways to fill all of those slots — with sound boards, 80-column video boards, hard-disk and printer interfaces, modems, co-processor and accelerator cards, mouse interfaces, higher resolution graphics boards, video and audio digitizers, ad infinitum. The slots, combined with Woz’s dogged insistence that every technical nuance of his design be meticulously documented for the benefit of hackers everywhere, transformed the Apple II from a single, static machine into a dynamic engine of possibility. They are the one feature that, more than anything else, distinguished the Apple II from its contemporaries the PET and TRS-80, and allowed it to outlive those machines by a decade. Within months of the Apple II’s release, even Jobs would have reason to thank Woz for their existence.

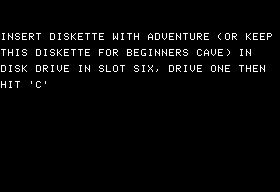

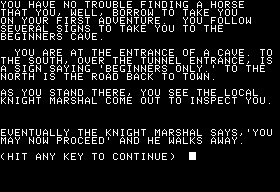

All of the trinity of 1977 initially relied on cassette tapes for storage. Both the PET and TRS-80 in fact came with cassette drives as standard equipment, while the Apple II included only a cassette interface, to which the user was expected to connect her own tape player. A few months’ experience with this storage method, the very definition of balky, slow, and deeply unreliable, convinced everyone that something better was needed if these new machines were to progress beyond being techie toys and become useful for any sort of serious work. The obvious solution was the 5 1/4 inch floppy-disk technology recently devised by a small company called Shugart Associates. Woz soon set to work, coming up with a final design that engineers who understand such things still regard with reverence for its simplicity, reliability, and efficiency. The product, known as the Disk II, arrived to market in mid-1978 for about $600, vastly increasing the usability and utility of the Apple II. Thanks to the expandability Woz had designed into the Apple II from the start, the machine was able to incorporate the new technology effortlessly. Even at $600, a very competitive price for a floppy-disk system at the time, Woz’s minimalist design aesthetic combined with the Apple II’s amenability to expansion meant that Apple made huge margins on the product; in West of Eden, Frank Rose claims that the Disk II system was ultimately as important to Apple’s early success as the Apple II itself. The PET and TRS-80 eventually got floppy-disk drives of their own, but only in a much uglier fashion; a TRS-80 owner who wished to upgrade to floppy disk, for instance, had to first buy Radio Shack’s bulky, ugly, and expensive “expansion interface,” an additional big box containing the slots that were built into the Apple II.

Another killer app enabled by the Apple II’s open architecture had a surprising source: Microsoft. In 1980, that company introduced its first hardware product, a Zilog Z80 CPU on a card which it dubbed the SoftCard. An Apple II so equipped had access to not only the growing library of Apple II software but also to CP/M and its hundreds of business-oriented applications. It gave Apple II owners the best of both worlds for just an additional $350. Small wonder that the card sold by the tens of thousands for the next several years, until the gradual drying up of CP/M software — a development, ironically, for which Microsoft was responsible with its new MS-DOS standard — made it irrelevant.

While most 6502-based computers were considered home and game machines of limited “serious” utility, products like the SoftCard and the various video cards that let it display 80 columns of text on the screen — an absolute requirement for useful word processing — lent the Apple II the reputation of a machine as useful for work as it was for play. This reputation, and the sales it undoubtedly engendered, were once again ultimately down to all those crazy slots. In this sense the Apple II much more closely resembled the commodity PC design first put together by IBM in 1981 than it did any subsequent design from Apple itself.

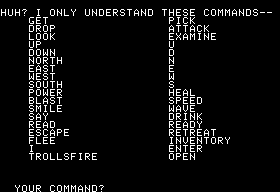

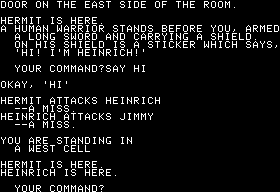

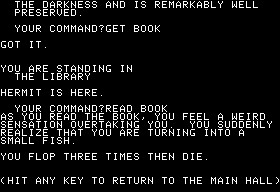

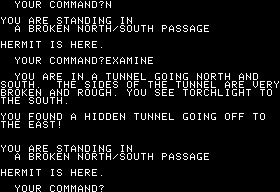

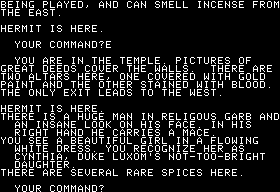

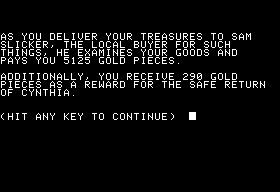

Another significant advantage that the Apple II had over its early competitors was its ability to display bitmap graphics. The TRS-80 and the PET, you may recall, were essentially limited to displaying text only. While it was possible to draw simple pictures using the suite of simple shape glyphs these machines provided in addition to traditional letters and punctuation (see my post on Temple of Apshai on the TRS-80), this technique was an inevitably limited one. The Apple II, however, provided a genuine grid of 280 X 192 individually addressable pixels. Making use of this capability was not easy on the programmer, and it came with a host of caveats and restrictions. Just 4 colors were available on the original Apple II, for instance, and oddities of the design meant that any individual pixel could not always be any individual desired color. These circumstances led to the odd phasing and color fringing that still makes an Apple II display immediately recognizable even today. Still, the Apple II was easily the graphical class of the microcomputer field in 1977. (I’ll talk a bit more about the Apple II’s graphical system and its restrictions when I look at some specific games in future posts.)

So, Woz was all over the Apple II, in these particulars as well as many others. But where was Jobs?

He was, first of all, performing the role he always had during his earlier projects with Woz, that of taskmaster and enabler. Left to his own devices, Woz could lose himself for weeks in the most minute and ultimately inconsequential aspects of a design, or could drift entirely off task when, say, some new idea for an electronically enabled practical joke struck him. Jobs therefore took it upon himself to constantly monitor Woz and the pair of junior engineers who worked with him, keeping them focused and on schedule. He also solved practical problems for them in that inimitable Steve Jobs way. When it became apparent that it was going to be very difficult to design the RF modulator needed for hooking the computer up to a television (dedicated monitors at the time were a rare and pricy luxury) without falling afoul of federal RF interference standards, he had Woz remove this part from the computer entirely, passing the specifications instead on to a company called M&R Electronics. When sold separately and by another company, the RF modulator did not need to meet the same stringent standards. Apple II owners would simply buy their RF modulators separately for a modest cost, and everyone (most of all M&R, who were soon selling the little gadgets by the thousands) could be happy.

Such practical problem-solving aside, Jobs’s unique vision was also all over the finished product. It was Jobs who insisted that Woz’s design be housed within a sleek, injection-molded plastic case that looked slightly futuristic, but not so much as to clash with the decor of a typical home. It was Jobs who gave the machine its professional appearance, with its screws all hidden away underneath and with the colorful Apple logo (a reference to the machine’s unique graphical capabilities) front and center.

Jobs, showing a prejudice against fan noise that has continued with him to the present day, insisted that Woz and company find some other way to cool it, which feat they managed via a system of cleverly placed vents. And it was Jobs who gave the machine its unique note of friendly accessibility, via a sliding top giving easy access to the expansion slots and, a bit further down the line, unusually complete and professional documentation in the form of big, glossy, colorful manuals. Indeed, much of the Apple II ownership experience was not so far removed from the Apple ownership experience of today. Jobs worked to make Apple II owners feel themselves part of an exclusive club, a bit more rarified and refined than the run-of-the-mill PET and TRS-80 owners, by sending them freebies and updates (such as the aforementioned new manuals) from time to time. And just like the Apple of today, he was uninterested in competing too aggressively on price. If an Apple II cost a bit more — actually, a lot more, easily twice the price of a PET or TRS-80 — it was extra money well spent. Besides, what adds an aura of exclusivity to a product more effectively than a higher price? What we are left with, then, is a more expensive machine, but also an unquestionably better machine than its competitors, and — a couple of years down the road at least, once its software library started to come up to snuff — one uniquely suited to perform well in many different roles for many different people, from the hardcore hacker to the businessman to the teacher to the teenage videogamer.

When the Apple II made its debut at the first West Coast Computer Faire in April of 1977, Jobs’s promotional instincts were again in evidence. In contrast to the other displays, which were often marked with signs hand-drawn in black marker, Apple’s had a back-lit plexiglass number illuminating the company’s new logo; it still looks pretty slick even today.

In light of the confusion that still exists over who deserves the credit for selling the first fully assembled PC, perhaps we should take a moment to look at the chronology of the trinity of 1977. Commodore made the first move, showing an extremely rough prototype of what would become the PET at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January of 1977. It then proceeded to show progressively less rough prototypes at the Hannover Messe in March (a significant moment in the history of European computing) and the West Coast Computer Faire. However, the design was not fully finalized until July, and the first units did not trickle into stores until September. Even then, PETs remained notoriously hard to come by until well into 1978, thanks to the internal chaos and inefficiency that seemed endemic to Commodore throughout the company’s history. (Ironically, Jobs and Woz had demonstrated the Apple II technology privately to Commodore as well as Atari in 1976, offering to sell it to them for “a few hundred thousand” and positions on staff. They were turned down; Commodore, immensely underestimating the difficulty of the task, decided it could just as easily create a comparable design of its own and begin producing it in just a few months.) The TRS-80, meanwhile, was not announced until August of 1977, but appeared in Radio Shack stores in numbers within weeks of the PET to become by several orders of magnitude the biggest early seller of the trinity. And the Apple II? Woz’s machine was in a much more finished state than the PET at the West Coast Computer Faire, and began shipping to retailers almost right on schedule in June of 1977. Thus, while Commodore gets the credit for being the first to announce a pre-built PC, Apple was the first to actually follow through and ship one as a finished product. Finally, Radio Shack can have the consolation prize of having the first PC to sell in large numbers — 100,000 in just the last few months of 1977 alone, about twice the quantity of all other kit or preassembled microcomputers sold over the course of that entire year.

Actually, that leads to an interesting point: if Apple’s status as the maker of the first PC is secure, it’s also true that the company’s rise was not so meteoric as popular histories of that period tend to suggest. As impressive as both the Apple II and Jobs’s refined presentation of it was, Apple struggled a bit to attract attention at the West Coast Computer Faire in the face of some 175 competing product showcases, many of them much larger if not more refined than Apple’s. Byte magazine, for instance, did not see fit to so much as mention Apple in its extensive writeup of the show. Even after the machine began to ship, early sales were not breathtaking. Apple sold just 650 Apple IIs in 1977, and struggled a bit for oxygen against Radio Shack with its huge distribution network of stores and immense production capacity. The next year was better (7600 sold), the next even better (35,000 sold, on the strength of increasingly robust software and hardware libraries). Still, the Apple II did not surpass the TRS-80 in total annual sales until 1983, on the way to its peak of 1,000,000 sold in 1984 (the year that is, ironically, immortalized as the Year of the Macintosh in the popular press).

Apple released an enhanced version of the II in 1979, the Apple II Plus. This model usually shipped with a full 48 K of RAM, a very impressive number for the time; the original Apple II had initially had only 4 K as standard equipment. Also notable was the replacement in ROM of the original Integer BASIC, written by Woz himself years ago when he first started attending Homebrew Computer Club meetings, with the so-called AppleSoft BASIC. AppleSoft corrected a pivotal flaw in the original Integer BASIC, its inability to deal with floating-point (i.e., decimal) numbers. This much more full-featured implementation was provided, like seemingly all microcomputer BASICs of the time, by Microsoft. (As evidenced by AppleSoft BASIC and products like the SoftCard, Microsoft often worked quite closely with Apple during this early period, in marked contrast to the strained relationship the two companies would develop in later years.) Woz also tweaked the display system on the II Plus to manage 6 colors in hi-res mode instead of just 4.

By 1980, then, the Apple II had in the form of the II Plus reached a sort of maturity, even though holes — most notably, a lack of support for lower-case letters without the purchase of additional hardware — remained. It was not the best-selling machine of 1980, and certainly far from the cheapest, but in some ways still the most desirable. Woz’s fast and reliable Disk II design coupled with the comparatively cavernous RAM of the II Plus and the machine’s bitmap graphics capabilities gave inspiration for a new breed of adventure games and CRPGs, larger and more ambitious than their predecessors. We’ll begin to look at those developments next time.

In the aftermath of even the Apple II’s first, relatively modest success, Jobs began working almost immediately to make sure Apple’s follow-up products reflected only his own vision of computing, gently easing Woz out of his central position. He began to treat Woz as something of a loose cannon to be carefully managed after Woz threatened Apple’s legendary 1980 IPO by selling or even giving away chunks of his private stock to various Apple employees who he just thought were doing a pretty good job and deserved a reward, gosh darn it. The Apple III, also introduced in 1980, was thus the product of a more traditional process of engineering by committee, with Woz given very little voice in the finished design. It was also Apple’s first failure, largely due to Jobs’s overweening arrogance and refusal to listen to what his engineers were telling him. Most notably, Jobs insisted that the Apple III, like the Apple II, ship without a cooling fan. This time, no amount of clever engineering hacks could prevent machines from melting by the thousands. Perhaps due to the deeply un-Jobs-ian hackerish side of its personality, Jobs tried repeatedly to kill the Apple II, with little success; it remained the company’s biggest seller and principal source of revenue when he resigned from Apple in a huff following an internal dispute in 1985.

In February of 1981, Woz crashed the small airplane he had recently learned how to fly, suffering serious head trauma. This event marked the end of his truly cutting-edge engineering years, at Apple or anywhere else. Perhaps he took the crash as a wake-up call to engage with all those other wonders of life he’d been neglecting during the years he’d spent immersed in circuits and code. It’s also true, though, that the sort of high-wire engineering Woz did throughout the 1970s (not only with Apple and privately, but also with Hewlett Packard) is very mentally intense, and possibly Woz’s brain had been changed enough by the experience to make it no longer possible. Regardless, he began to interest himself in other things: going back to university under an assumed name to finish his aborted degree, organizing two huge outdoor music and culture festivals (The “US Festivals” of 1982 and 1983), developing and trying to market a universal remote control. He is still officially an employee of Apple, but hasn’t worked a regular shift in the office since February of 1987. He wrote an autobiography (with the expected aid of a professional co-author) a few years ago, maintains a modest website, contributes to various worthy causes such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and, most bizarrely, made a recent appearance on Dancing with the Stars.

Asked back in 2000 if he considered himself an entrepreneur, Woz had this to say:

Not now. I’m not trying to do that because I wouldn’t put 20 hours a day into anything. And I wouldn’t go back to the engineering. The way I did it, every job was A+. I worked with such concentration and focus and I had hundreds of obscure engineering or programming things in my head. I was just real exceptional in that way. It was so intense you could not do that for very long—only when you’re young. I’m on the board of a couple of companies that you could say are start-ups, so I certainly support it, but I don’t live it. The older I get the more I like to take it easy.

Woz has certainly earned the right to “take it easy,” but there’s something that strikes me a little sad about his post-Apple II career, as the story of a man who never quite figured out what to do for a second act in life. And the odd note of subservience that always marked his relationship with Jobs is still present. From the same interview:

You know what, Steve Jobs is real nice to me. He lets me be an employee and that’s one of the biggest honors of my life. Some people wouldn’t be that way. He has a reputation for being nasty, but I think it’s only when he has to run a business. It’s never once come out around me. He never attacks me like you hear about him attacking other people. Even if I do have some flaky thinking.

It’s as if Woz, God bless his innocence, still does not understand that he was really treated rather shabbily by Jobs, and that, in a very real sense, it was he that made Jobs. In that light, it seems little enough to expect that Jobs refrain from hectoring him as he would one of his more typical employees.

As for Jobs himself… well, you know all about what became of him, right?