When we last left Scott Adams at the end of 1979, he was poised to take this adventuring thing to the proverbial next level, with a solid catalog of games already available on a number of platforms, with perhaps the best name recognition in the nascent computer-game industry, and with a new company — Adventure International — ready to publish his works and the works of others under its own imprint. The following year saw him realize all of that potential and more, to take a place at the forefront of a new industry.

Adventure International grew by leaps and bounds for the next few years, while always remaining, like everything Adams touched, indelibly stamped with the personality of its founder. AI was the Dollar General of the early software industry. Its catalogs are filled with a ramshackle collection of software of every stripe. In addition to the expected text adventures from Adams and others (many of these also using Adams’s engine), there were arcade clones (“far superior to any Space Invader game for the TRS-80 microcomputer so far”, announces the blurb for Invaders Plus, with more honesty than legal wisdom); space strategy games (Galactic Empire and Galactic Trader); chess programs (“although a graphic display of the chessboard is provided, it is recommended that an actual chessboard be used during play…”); board game adaptations (Micropoly, which is once again foolish enough to advertise that it is a clone of Monopoly right in the promotional text); even TRS-80 Opera, which let one listen to the William Tell overture via a transistor radio set in close proximity to the machine’s cassette port (the TRS-80’s lack of proper RF shielding was not always such a bad thing). And for when fun-and-games time was over, there were also math programs, print spoolers, programming tools, drawing programs, and educational software to hand, the latter evincing the usual fascination with states and their capitals that was so common amongst early programmers. All of this software was relatively cheap, with $9.95 or $14.95 being the most common price points, and somewhat… variable… in quality. Still, there was a thrill to be had in walking the virtual aisles of the AI catalogs, gazing at the shelves groaning with the output of an expanding new industry, wondering what crazy (not to say hare-brained) idea would be around the next bend. Hovering over the whole scene was always the outsized personality of Adams himself, who would remain throughout AI’s brief but busy lifetime an unusually visible company leader. (A reading of the legal fine print shows AI itself to be merely “a division of Scott Adams, Inc.”)

The year 1980 represents an important historical moment for the entertainment-software industry. A few exceptions such as Microsoft and Automated Simulations aside, computer games had previously been distributed as a sideline by semi-amateurs who hung their Ziploc baggies up in the local computer store and signed up with the hobbyist distribution services run by SoftSide and Creative Computing magazines. Now, though, companies like AI and a few others that sprung up around the same time began to professionalize the field. Within a few years the Ziploc baggies would be replaced with slick, colorful boxes stuffed with glossy manuals and other goodies, and the semi-amateurs in their home offices and bedrooms with real development studios whose members did this stuff for a living. Computer games were becoming a viable business, bringing more resources onto the scene that would soon allow for bigger and more ambitious creations than anything yet seen, but also bringing all the complications and loss of innocence associated with monetizing a labor of love.

In light of the explosive growth of his company, it’s no surprise that Adams’s creation of new adventures slowed down dramatically at this point. Some of his energy was consumed — and not for the last time — with repackaging his already extant games. All received pen-and-watercolor cover illustrations courtesy of an artist known as “Peppy,” whose colorful if unpolished style perfectly suited the gonzo enthusiasm of Adams’s prose.

AI released just two new Adams-penned adventures in 1980: the Western pastiche Ghost Town in the spring and Savage Island Part One, first of a two-parter advertised as difficult enough for the hardcore of the hardcore, just in time for Christmas. I thought we’d take a closer look at the first of these to see how far Adams’s art had progressed since The Count.

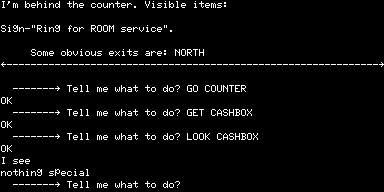

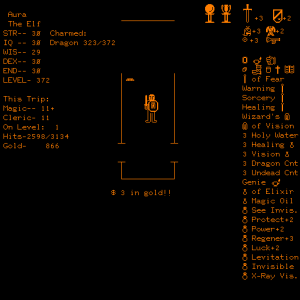

The simple but painful answer to that question is: not at all, really. In fact, it has regressed in many ways. The Western setting was apparently merely the next on Adams’s list of genre touchstones to cover, as it does little to inform the experience of play. Ghost Town is a plotless treasure hunt, just like Adventureland; it’s as if the The Count never happened: “Drop treasures then score.” Sigh.

We rob the saloon of its cash box just because it’s there. Double sigh.

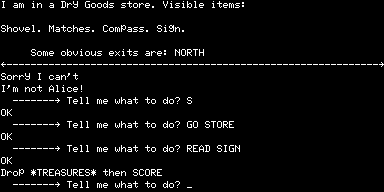

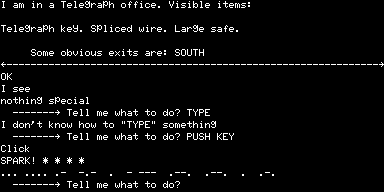

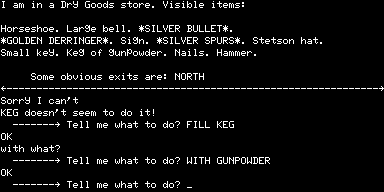

Worse, even as a treasure hunt Ghost Town is neither entertaining nor satisfying. A few quips such as the response to trying to GO MIRROR (“I’m not Alice!”) aside, Ghost Town has lost some of the friendly warmth that made one somewhat willing to forgive the earlier games their own dodgy moments. The useful HELP command with its little nudges and food for thought has disappeared entirely, while the puzzles have devolved into a veritable catalog of design sins. Adams had been slowly ramping up the difficulty of each successive game that he wrote, apparently expecting his player to work through the games in order and thus to be prepared by the time they faced Ghost Town. I suppose that’s a reasonable enough approach in the abstract, but in reality there is no way to train for the puzzles in Ghost Town. Even some of the least objectionable require considerable outside knowledge, of things like the composition of gunpowder or the translation of Morse code.

Of course, in 1980, a time when Wikipedia was not a browser bookmark away, tracking down this sort of information might require a trip to the local library.

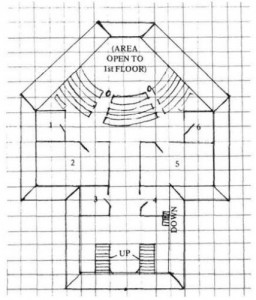

Other puzzles require us to see the room in question exactly as Adams pictured it, despite his famously terse room descriptions that do little more than list the objects therein. Still others reward only dogged persistence rather than insight, such as requiring us to tote a shovel around the map and dig in every single room to see whether anything turns up. Yet more, the worst of all, are protracted battles with the parser. How long it would take the average player to divine that she must SAY GIDYUP to get the horse to move is something I don’t even want to think about — nor how long she might fruitlessly try mixing the charcoal, sulfur, and saltpeter together before finally just typing MAKE GUNPOWDER. At times the parser seems not just technically limited but intentionally cruel.

Typing just GUNPOWDER as opposed to WITH GUNPOWDER at the above prompt results in a generic failure message. My experience with Ghost Town makes me more enamored than ever of the idea that these early games were simply too technologically limited to support difficult puzzles that were also fair and logically tenable, that ramping up their difficulty beyond a certain rather low threshold inevitably resulted in nonsense like so many of the puzzles in Ghost Town and the absurd end-game of Adventure.

It’s also tempting to conclude that Adams himself simply lacked the vision to continue to push the text adventure forward. Tempting, but not entirely correct. For a couple of years Adams wrote an occasional column for SoftSide magazine. In the November, 1980, edition he announced a planned new adventuring system called Odyssey, which would take advantage of disk-drive-equipped systems in the same way as did Microsoft Adventure, using all of that storage space as an auxiliary memory store. His plans were ambitious to say the least:

1. More than one player in an Odyssey at one time. Players may help (or hinder) one another as they see fit!

2. Full paragraphs instead of “baby talk,” e.g., “Shoe the horse with the horseshoe and the hammer and nails.”

3. Longer messages;

4. sound effects; and

5. expanded plot lines.To develop this system I have actually had to develop a new type of computer language which I call OIL (Odyssey Interpretive Language) which is implemented by a special Odyssey assembler that generates Odyssey machine code. This machine code is then implemented on each different micro, e.g. Apple, TRS-80, etc., through a special host emulator to simulate my nonexistent Odyssey computer.

Currently (as of the Washington computer show, Sept., 1980) the system is in the final stages of implementing a host emulator on a TRS-80 32 K disk system and writing the first Odyssey (which has been sketched out and is tentatively entitled Martian Odyssey) in OIL to run on the emulator. I hope that by the time you are reading this, Odyssey Number One will be available from your local computer store or favorite mail order house.

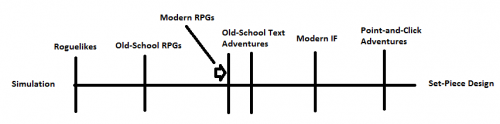

The technical conception of Odyssey sounds remarkably similar to what would soon be rolled out by a tiny Massachusetts startup called Infocom. Interestingly, Marc Blank and Stu Galley of Infocom had laid out in the abstract the design of their virtual machine, the “Z-Machine,” in an article in Creative Computing just a couple of months before Adams wrote these words. Could he have been inspired by that article?

Whatever the answer to that question, Martian Odyssey of course never appeared, and to my knowledge Adams never mentioned the Odyssey system again. For better and (ultimately) for worse, he elected to stick with what had brought him this far — meaning treasure hunts runnable on low-end 16 K computers equipped only with cassette drives. That strategy would continue to pay off handsomely enough for a few more years, yet it’s hard not to wonder about the path not taken, the territory ceded without a fight to Infocom and others. From 1980 on, Adams is more interesting as a businessman and an enabler for others than as a software artist in his own right. On that note, I want to talk about a few of the more interesting creations to stand alongside Adams’s own adventures in the jumble of the Adventure International catalog next time.

If you’d like to try Ghost Town, here’s a version you can load into the MESS emulator using its “Devices -> Quickload” function.