The Commodore/Amiga honeymoon could hardly have been more idyllic. Honoring the wishes of everyone at Amiga to not get shipped off to Commodore’s headquarters in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Commodore instead moved them just ten miles from their cramped offices in Santa Clara, California, to a spacious new facility in Los Gatos, surrounded by greenery and well-tended walking paths that gave it something of the atmosphere of a university campus. The equipment at their disposal was correspondingly upgraded; instead of fighting one another for the use of a handful of aging Sage IV workstations, everyone in a significant technical role now got a brand new Sun workstation of his own. Best of all, Commodore knew when to back off. With their charges now relocated and properly equipped, they left them to it. “Commodore,” says R.J. Mical, “did the best thing they possibly could have done to make sure the product they bought was successful. They left us alone.” They were all “vastly in love with Commodore” in those early days. After all they’d just been through, how could they not be?

With Jay Miner’s chipset, the heart of their project, largely complete before the acquisition, Amiga’s focus now shifted to all of the stuff that would need to surround those chips to finish their computer, now to be called not the Amiga Lorraine but the Commodore Amiga. The need for an operating system becoming urgent, the software folks now came to the fore. The three most prominent systems programmers at Amiga each authored one layer of the software stack that would become the soul of the machine. Carl Sassenrath wrote the Exec, the kernel of a new operating system that borrowed many ideas from bigger institutional operating systems like Unix, not least among them the revolutionary capability of true preemptive multitasking. Atop that Dale Luck layered the Graphics Library, a collection of software hooks to let programmers unlock the potential of Miner’s chipset in a multitasking-friendly way, without having to bang on the hardware itself. And atop that R.J. Mical layered Intuition, a toolbox of widgets, icons, menus, windows, and dialogs to let programmers build GUI applications with a consistent look and feel.

But even as the rest of the system was coming together around it, Miner continued to tinker with his chipset. Out of these late experiments arose one of the most important capabilities of the Amiga, one absolutely key to its status as the world’s first multimedia PC. In the Amiga’s low-resolution modes of 320 X 200 and 320 X 400, Denise was normally capable of displaying up to 32 colors chosen from a palette of 4096. Miner now came up with a way of displaying any or all 4096 at once, using a technique he called “hold and modify” whereby Denise could create the color of each pixel by modifying only the red, green, or blue component of the previous pixel. He hoped it would allow programmers to create photorealistic environments for flight simulators, a special interest of his. When he realized that HAM mode updated too slowly to offer a decent frame rate for such applications, he actually requested that it be removed again from the chipset. But the chip fabricators said it would cost precious time and money to do so, and since it wasn’t hurting anything they might as well leave it in. Thank God for those bean counters. While it would indeed prove of limited utility for flight simulators and other games, HAM would allow the Amiga to display captured photographs of the real world. As advertisements for Digi-View, the first practical photorealistic digitizer to reach everyday computers, would soon put it, “Digi-View brings the world into your Amiga!” It’s that very blending of the analog world around us with the digital world inside the computer that is the key to the multimedia experience that the Amiga was first to provide. HAM mode stands as a classic object lesson in unintended consequences of technological innovation. The Amiga’s claim to historical importance would have been much shakier without it.

As 1984 turned into 1985, Commodore’s patience with the sort of endless tinkering that had led to HAM mode began to decrease; they wanted Los Gatos to just get the Amiga done already. The splashy debut the Atari ST made at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January spooked the brass back in West Chester. And by the spring of 1985, with the home-computer market clearly on the downturn, Commodore’s financial position was beginning to look downright precarious. They needed the Amiga, and soon.

A new hire named Howard Stolz, young and inexperienced like so many of the others, became the project’s unsung hero by crafting the external appearance for the new computer. His sleek, trim case still looks great today; whatever else you can say about that first Amiga model, it remains to this day by far the best looking Amiga ever released. Then and now, one is first struck upon seeing it by how small it is; even Apple’s contemporaneous machines look chunky and clunky next to it. And it’s full of thoughtful little touches, like the “garage” below the system unit into which one can slide the keyboard when not in use. Imprinted on the inside cover of the system unit are the signatures of the core Amiga team, an idea borrowed from the original Apple Macintosh. Amongst them is the paw print of Jay Miner’s beloved Mitchie.

The Amiga made its public debut at last on July 23, 1985, in the most surreal event in the long history of Commodore. Obviously hoping to duplicate the sort of excitement Apple had become so adept at evoking, Commodore rented New York’s Lincoln Center to put on a show the likes of which they never had before and never would again. The black-tie event sported an open bar stocked to the nines, waiters wandering through the crowd with plates of hors d’oeuvres, a laser show, a three-piece classical-music trio, and — no, really — a ballerina twirling across the stage. The Los Gatos team were all there, crammed awkwardly into rented tuxedos. Bob Pariseau, the traditional master of ceremonies of Amiga demos since the days when the Amiga Lorraine was just a tangled mass of wires and breadboards, once again narrated the proceedings, looking like a stage magician in his tux and long ponytail. The rabbit he pulled out of his hat for the occasion was perhaps the only computer in the world at that time that could have managed not to be overshadowed by all the pomp and circumstance. The crowd erupted into spontaneous applause on several occasions: when, thanks to HAM mode, the Amiga showed all 4096 colors onscreen at once; when the Amiga played a bit of “Smoke on the Water” in an appropriately distorted electric-guitar tone; when it talked in male and female voices; when that old favorite, Boing, showed up yet again. The evening concluded with Andy Warhol coming onstage to digitize and manipulate the image of Debbie Harry of Blondie fame, creating an end result reminiscent of his famous Marilyn Diptych of 1962. The Amiga, everyone had to agree, made for one hell of a show.

The Amiga enjoyed the best press of its career in the immediate aftermath of that Lincoln Center premiere, ironically well before anyone could actually buy one. Byte magazine, whose editorial voice was easily the most respected in the industry, devoted a luxurious 13 pages to a detailed technical preview of the machine, pronouncing it “the most advanced and innovative personal computer today.” Creative Computing, the industry’s most venerable and (often) most visionary publication, was even more effusive in its praise. The Amiga was not just a new computer but “a new communications medium — a dream machine, a new medium of expression” that the reviewer pronounced literally indescribable in print. Writing for Computer Gaming World, Jon Freeman pronounced that “anything your favorite computer can do, the Amiga can do better. And faster. And in stereo.”

Freeman published his games through Electronic Arts, and in writing his article on the machine was very much toeing his publisher’s line. By far the new computer’s most enthusiastic and stalwart supporter, who had followed it with interest since well before the Commodore acquisition, was EA. Trip Hawkins, still nursing his dream of EA software titles lined up on the shelf of every hipster aesthete alongside the music albums they were consciously packaged to evoke, just got right away what the Amiga could mean for computerized entertainment. For him it was the Great White Hope for an industry suffering through its first real downturn ever and struggling to understand just what had gone wrong. Receiving their first prototypes many months before the Lincoln Center premiere, EA had worked hand-in-hand with Los Gatos to refine the machine and get a jump start on writing software for it.

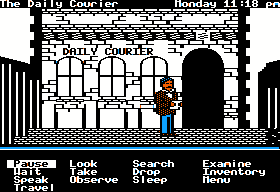

Thus much of the earliest software available for the Amiga came from EA, including ports of old favorites like Archon and Seven Cities of Gold as well as new titles destined to become Amiga icons: DeluxePaint, Arcticfox, Marble Madness. In the immediate wake of the Amiga’s release, while most publishers were adopting a wait-and-see position on the new machine, EA offered full-throated support via splashy multi-page editorials that ran in just about every publication in the industry.

The Amiga will revolutionize the home-computer industry. It’s the first home machine that has everything you want and need for all the major uses of a home computer, including entertainment, education, and productivity. The software we’re developing for the Amiga will blow your socks off. We think the Amiga, with its incomparable power, sound, and graphics, will give Electronic Arts and the entire industry a very bright future.

We believe that one day soon the home computer will be as important as radio, stereo, and television are today.

But so far, the computer’s promise has been hard to see. Software has been severely limited by the abstract, blocky shapes and rinky-dink sound reproduction of most home computers. Only a handful of pioneers have been able to appreciate the possibilities. But then, popular opinion once held that television was only useful for civil-defense communications.

The Amiga is advancing our medium on all fronts. For the first time, a personal computer is providing the visual and aural quality our sophisticated eyes and ears demand. Compared to the Amiga, using some other home computers is like watching black-and-white television with the sound turned off.

For the first time, software developers have the tools they need to fulfill the promise of home computing.

Two years ago, we said, “We See Farther.” Now Farther is here.

With praise like that, how could anything go wrong?

Well, anything could, and for a while there it seemed like just about everything did. After the premiere and the rapturous press it generated, much momentum was squandered as Commodore struggled to put the finishing touches on the Amiga and get the machine, so much more complicated than anything the company had built or supported before, into production. It wasn’t until November that one could hope to walk into a store and walk out with a new Amiga. Commodore’s advertising campaign that started up then was as unfocused as a confetti cannon. In lieu of a coherent argument for what the Amiga represented and why it mattered, Commodore gave the public black-and-white footage of the Baby Boom Generation and tired rhetoric about keeping up with the Joneses. Commodore had somehow decided that the best way to sell the most futuristic, technologically advanced computer on the market was to evoke… nostalgia.

Just why did EA seem to understand what the Amiga represented so much better than Commodore themselves? Why was EA so much better at selling Commodore’s computer than Commodore? EA unhesitatingly and unreservedly laid out a compelling case for the Amiga as a revolutionary technology for home entertainment. Meanwhile Commodore hedged their bets everywhere — except in the Amiga’s most obvious application as a game machine, from which they ran terrified.

Then, within weeks of the Amiga’s arrival in stores, Commodore’s advertising disappeared completely. The reason was a pretty basic one: Commodore simply couldn’t afford to pay for it anymore. The previous year had been so disastrous that they were suddenly teetering on the verge of bankruptcy.

After that magical year of 1983, when Commodore had briefly become a billion-dollar company and briefly been even bigger than Apple, there had been little but bad news on the financial front. 1984 had marked a gradual cooling of the excitement surrounding home computers. That was a problem for many companies, but few more so than Commodore: Commodore represented fully 60 percent of the home-computer hardware market by that point, and had long since axed all of their more expensive machines. For them 1984 brought the failure of the eminently fail-worthy Plus/4, an alarming buildup of Commodore 64 inventories, and a disappointing Christmas that failed to come close to the previous one. And yet their troubles were only just beginning.

In 1985 a slowing home-computer market turned into a collapsing home-computer market. Suddenly Commodore was posting massive losses, to the tune of almost $200 million in 1985 alone. Their mounting debt amounted to about the same figure. By the beginning of 1986 their unsold inventory amounted to almost half a billion dollars, and layoffs had halved their workforce from 7000 to 3500. Not only was Commodore forced to effectively give up on advertising the Amiga in the mainstream media, but they didn’t even go to the biggest party in their own industry, Winter CES, in January of 1986; they simply couldn’t afford to. Ahoy! magazine pronounced Commodore’s absence akin to “Russia resigning from the Soviet Bloc, Sly leaving the Family Stone.”

Most of the people who bought home computers in 1982 and 1983 had bailed out quickly once they realized how limited their machines really were, while the remainder already had their Commodores 64s, thank you very much. And the rest of the population, the ones who were supposed to keep buying and buying for years to come, simply weren’t interested anymore. What was Commodore supposed to do, saddled as they were with bloat like the massive West Chester campus that Jack Tramiel had bought for them at the height of 1983’s success, which they hadn’t been able to even begin to fill even then?

That was a question that lots of bankers were now asking themselves because Commodore had now fallen into default of their debt obligations. The financial community wasn’t inclined to take very much on faith when it to came to this company to which an air of the fly-by-night had always clung even in its glory years. Thus it came down to a hard-headed calculus. Was their best bet to demand their payments, forcing Commodore into bankruptcy and liquidation and giving the loaners a chance to recoup what they could? Or would it be better to wait and see if things looked likely to turn around? For agonizing weeks they held Commodore’s future in their hands while the Wall Street Journal and business pages around the world speculated on the over-under of the company being forced to fold. At last, in March of 1986, a deal was reached: Commodore would get another loan package worth $135 million with which to service their existing debt and fund their efforts to turn things around. It amounted to a lease on life of about one year.

The doors would stay open for the time being, but Commodore was now known far and wide — not least to potential Amiga buyers — as a company teetering on the edge of a financial cliff. And even if you decided it was worth risking such a major purchase from a company that looked very likely to leave the Amiga an orphan, you still had to find someplace to actually buy one. Therein lies a tale in itself.

There were two entirely separate distribution channels for computers in the mid-1980s: the network of specialized dealers, who offered service, advice, and support along with computers to their customers; and the mass merchants, big-box stores like Sears and Toys ‘R’ Us and the big consumer-electronics chains, who sold computers alongside televisions and washing machines and offered little to nothing in the way of support, competing instead almost entirely on the basis of price. Commodore under Jack Tramiel had pioneered the latter form of distribution with the VIC-20, the first truly mass-market home computer. Most people were happy to buy a relatively cheap machine, especially one meant for casual home use, through a big-box store. Those spending more money, and especially those buying a machine for use in business, preferred to safeguard their investment by going through a dealer. Thus Apple, IBM, and the many makers of IBM clones like Compaq continued to sell their more expensive machines through dealers. Commodore and Atari, makers of cheaper, home-oriented machines, sold theirs through the mass market.

Now, however, Commodore found themselves with a more expensive machine and no dealer network through which to sell it, a last little poison pill left to them by Jack Tramiel. One might say that Commodore was forced to start again from scratch — except that it was actually worse than that. In late 1982 Tramiel had destroyed what was left of Commodore’s dealer network when he dumped the successor to the VIC-20, the Commodore 64, into the mass-market channel as well, just weeks after promising his long-suffering dealers that he would do no such thing. That betrayal had put many of his dealers out of business, leaving the rest to sign on with other brands whilst saying, “Never again.” New Commodore CEO Marshall Smith was honestly trying in his stolid, conservative, steel-industry way to remove the whiff of disreputability that had always clung to the company under Tramiel. But the memories of most potential dealers were still too long, no matter how impressive the machine Commodore now had to offer them. The result was that many major American cities now sported, at best, just one or two places where you could walk in and buy an Amiga. It was a crippling disadvantage.

And so the Amiga’s early customers would largely come down to the hacker hardcore, who saw the Amiga for the revolutionary technology that it was and just couldn’t not have one, in spite of it all. The early issues of Amazing Computing, the first techie magazine to devote itself to the Amiga, have some of the flavor of the early issues of Byte. Hackers probed at the machine’s many mysteries — like this unexplained “HAM mode” that was supposed to allow one to do magical things — and published their findings for others to build upon. Given by Commodore no way to expand the Amiga beyond 512 K, they figured out how to roll their own memory expansions; ditto for hard drives. Faced with a dearth of commercial software, a fellow named Fred Fish started curating disks full of the best free software and distributing them at cost to dealers to pass on to customers; the Fred Fish Collection would eventually reach over 1100 disks. A fellow named Tim Jenison devised a digitizer and started distributing disks full of incredible full-color photographs. A fellow named Eric Graham wrote a 3-D modeller and ray tracer and started passing around a jaw-dropping animation called The Juggler that, when played in computer-shop windows, quite possibly sold more Amigas than all of Commodore’s own promotional efforts combined. User groups were formed all over the country, congregations of the Amiga faithful meeting in churches and the back rooms of public libraries. It was the last great flowering of the spirit of ’75 that had spawned the PC industry in the first place. Indeed, legendary Homebrew Computer Club member John Draper, the “Captain Crunch” who had taught Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs how to phone phreak and wrote the first practical Apple II word processor amongst other achievements, was a prominent early Amiga user. He figured out the vagaries of Intuition long before Commodore’s official documentation arrived, publishing code samples and technical tutorials, some of which were included on Fred Fish Disk #1. If the Amiga was destined to remain a cult computer, it was going to be one heck of an interesting cult.

Still, hackers with the requisite pioneering spirit and $2000 worth of disposable income weren’t in infinite supply. Sales were sluggish, if perhaps better than one might expect in light of the perfect storm of problems against which the Amiga struggled. Commodore sold about 140,000 Amigas in the first eighteen months — most in North America, some in Europe, where the machine was introduced at last only in June of 1986. As Britain’s Commodore User wryly put it, “the Amiga didn’t exactly blow the world away.”

While Commodore would have much preferred to compare the Amiga to the Macintosh, their image as a maker of low-end home computers was hard to shake. Thus the most common point of comparison in the press became Jack Tramiel’s new Atari ST line, whose earliest days in North America were far from perfect in their own right. The vast majority of the early STs shipped to Europe; of the 50,000 STs sold during the first three months, only about 10,000 were sold in North America. Like the Amiga, the ST was hobbled in North America by a sparse and shabby dealer network; even fewer dealers wanted anything to do with Jack Tramiel’s new Atari than were willing to get onboard again with the now Tramiel-less Commodore. In January Tramiel, true to his old Commodore 64 playbook, dumped the ST into the mass market. But even then distribution continued to be a problem. Most of the retailers who had filled their warehouses with Commodore 64s a couple of years ago were very skeptical of any new machines, no matter how impressive, given the moribund state of home computers in general.

Despite it all, Atari’s marketers proved to be very adept at conjuring a sense of excitement out of all proportion to the ST’s actual sales. For months it was conventional wisdom that the ST was trouncing the Amiga, outselling it by a margin of about three to one. But in September of 1986 the game was suddenly up. Preparatory to making a first IPO of 15 percent of their stock, Atari was forced to publish a prospectus detailing their actual sales numbers. They had, it turned out, sold only about 150,000 STs to that date, 90,000 of them in Europe. It seemed the Amiga was actually slightly outselling the ST in North America, although neither platform’s numbers were exactly breathtaking. Certainly the ST’s sales were a far cry from the millions per year Jack Tramiel had confidently predicted just before its launch. The much-vaunted return of the new, lean-and-mean Atari to slim profitability in 1986 was down at least as much to a modest nostalgia-driven revival of their videogame consoles, which sold cheap but could be made even cheaper, as it was to the new ST line. Likewise, Commodore’s new 8-bit 128 model was outselling the Amiga and ST combined by a factor of at least four to one, while the old 64 was continuing to sell even better than the 128.

Yet perception, as a wise someone once said, is often reality. Nowhere is that more clearly illustrated than in the way software publishers responded to the Amiga and the ST. Makers of games and other home-oriented software were already supporting quite a number of platforms. Many were understandably reluctant to add two more. Better to choose the likely winner of the 68000 Wars and support only that one. Buying into the conventional wisdom just like everyone else, most — with Electronic Arts the glaring exception — hitched their wagon to the Atari ST, which seemed to many of them the most logical likely successor to the Commodore 64. The relative positions of Commodore and Atari seemed to have neatly reversed themselves. A few years ago Atari had offered Jay Miner’s 8-bit line of computers, more technologically impressive than anything else in the industry but a bit on the expensive side and dogged by poor or nonexistent marketing. Commodore under Jack Tramiel had come along to trounce the Ataris with the Commodore 64, simple in design where the Ataris were baroque and in consequence much cheaper to make and sell. Now, with Tramiel in charge of Atari and Miner working with Commodore, history looked about to repeat itself in mirror image. The ST’s cause was helped by its being a more immediately accessible, understandable machine; the paradigm shift represented by the Amiga with its complex multitasking operating system placed many new demands on programmers, while the ST could pretty much be programmed like a super-Commodore 64.

Thus during 1986 many major game projects were begun on the ST rather than the Amiga, many older games ported to the ST but not the Amiga. The Amiga, despite the slim sales advantage it enjoyed at the moment, was threatened with a runaway chain reaction. As the industry was finally coming to understand, software availability was the single most important factor in most customers’ decision of which platform to buy into. These early commitments to the ST by so many publishers would result in more games and applications on the shop shelves for the ST, which would in turn result in more ST buyers, which would in turn encourage yet more software publishers to cast their lot with the ST, which would… you get the picture. Thus by the end of 1986 the mounting frustration and anger the Amiga faithful felt toward Commodore was mixed with more than a tinge of outright fear. How could Commodore, owners not only of the superior machine but the better-selling machine, have passively allowed Atari to control the narrative for so long? Nowhere was that frustration, anger, and fear more keenly felt than amongst the remnants of the old Amiga, Incorporated, in Los Gatos.

The team that had built the Amiga was gradually dispersing. David Morse, the man who had co-founded the company and so brilliantly jinked and weaved his way around Atari to bring it to a safe harbor at Commodore, was gone even before the Lincoln Center show, judging his work with Amiga essentially done and finding the life of a mere administrator to be less than enticing. Commodore installed a manager of their own at Los Gatos. Friction between the East and West Coast branches began to build from there. In December of 1985 R.J. Mical and Carl Sassenrath both left. Many others threatened to do so. They had to be begged and cajoled to stay at least long enough to properly finish the Amiga’s operating system, which had been released in a very imperfect state.

As the months passed and it became clear that the Amiga wasn’t becoming the mass-market sensation they’d so confidently expected, the folks at Los Gatos knew exactly who to blame. They regarded Commodore’s mishandling of the Amiga as nothing less than a personal betrayal. Someone printed up tee-shirts that they claimed to have found at Commodore’s marketing department: “Ready? Fire! Aim!” was printed on them. West Chester in turn saw Los Gatos as an arrogant bunch of youngsters who thought they were too cool for school. For evidence of just how far relations between Commodore and the Amiga old guard had deteriorated already by the spring of 1986, we need only look to the third revision of the operating system (version 1.2), which was being finished at that time. The Amiga folks had a habit of embedding secret messages into their software, little Easter eggs activated via obscure key sequences. Mostly these were the sort of things you might expect from talented young men a bit full of themselves: “INTUITION by =RJ Mical= Software Artist Deluxe”; “Carl EXEC Sassenrath reminds: All things are in Flux!”; “Brought to you by not a mere Wizard, but the Wizard Extraordinaire: Dale Luck.” In the aftermath of version 1.2’s release, however, word quickly spread through the Amiga community of an uglier message: “We made Amiga, They f−−−−− it up.” It didn’t take long for word to get back to West Chester; nor was it hard for them to guess who the “they” represented. It only hardened West Chester’s perception of Los Gatos as an undisciplined romper room full of immature and ungrateful prima donnas. In June of 1986 West Chester, apparently judging the operating system to be good enough for now, brought the axe down. A whole swathe of people were cut, including Bob Pariseau, the very face of Amiga at so many presentations and trade shows.

By year’s end Los Gatos was down from a high of 80 people to just 13, Jay Miner and Dale Luck the only leftovers among the core figures we’ve met in the course of these articles. Attending a developer’s conference at about that time, Amazing Computing reported that the hostility between the Los Gatos and West Chester people was now “almost palpable,” even in this public setting. This could only end one way. In March of 1987, with the lease running out on that wonderful Los Gatos campus, Commodore’s brief-lived West Coast branch was shuttered, the few remaining employees given predictably unenticing offers to move to West Chester, which they predictably refused.

The old guard held an “Amiga Wake” to mark the end of their part in the Amiga story. It was almost exactly five years to the day after Larry Kaplan had called up Jay Miner to ask if he knew any lawyers, and just days after Commodore and Atari had finally settled their long legal battle brought on by the events that followed. The theme of the party, complete with a casket at the center of the room, might easily convince one that this was a requiem not just for the team that had built the Amiga but for the dream of the Amiga itself. Given the Amiga’s commercial fortunes at that instant, it’s very possible that many who attended believed that to be exactly what it was. In actuality, though, the Amiga was just about to get a new lease on life in the form of two new models much more intelligently packaged, marketed, and, most of all, priced. The Atari ST also had brighter days ahead of it. Ironically, both platforms were destined to enjoy the best of their glory days not in North America, the continent they’d been built to conquer, but rather an ocean away in Europe. While the 68000 Wars had so far turned out to be more a slap-fight between two commercial pygmies than the titanic battle anticipated in the press, both of the principal combatants were just getting started.

(Sources: On the Edge by Brian Bagnall; Compute! of August 1985, September 1985, December 1985, and January 1987; Byte of August 1985, October 1985, and January 1987; Compute!’s Gazette of September 1985, November 1985, December 1985, and October 1986; InfoWorld of August 5 1985; Ahoy! of September 1985 and April 1986; Computer Gaming World of September/October 1985; Info of September/October 1985 and December/January 1986; Creative Computing of September 1985; New York Magazine of May 13 1985; New York Times of August 22 1985; Commodore User of June 1986; Amazing Computing of June 1986, January 1987, March 1987, and June 1987; Fortune of January 6 1986; PC Magazine of January 14, 1986; Commodore Magazine of May 1987; Atari ST User of November 1986. Whew!)