I started my article on Infocom’s 1983 with an unsung hero, Dan Horn of the Micro Group. Let’s continue that tradition now that we’ve come to 1984 with another: Jon Palace.

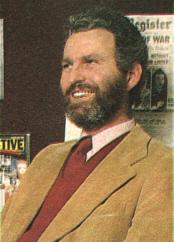

As 1984 dawned, Palace was working as a textbook editor for McGraw-Hill Higher Education in New York City. Wanting to live pretty much anywhere else, he scoured the want ads for jobs as far away as Madison, Wisconsin, and Chicago, Illinois. Then he stumbled across an advertisement in the Boston Globe Magazine from a company he had never heard of: Infocom. Palace had no real idea what Infocom did or what an adventure game was or what exactly they might expect him to do, but he duly applied and was granted an interview. He drove up to Boston one snowy day to sit down with Marc Blank and Mike Berlyn. He knew this was a different sort of operation than the staid, corporate McGraw-Hill when Blank asked him how old he was. “You can’t ask me that in an interview!” Palace replied, shocked, “… but I’m 27.” Blank seemed to like that answer; that was about the average age at Infocom, he noted.

Technology companies in those days still had a bit of a reputation. Palace remembered (almost certainly hyperbolic) accounts he’d read of life at Apple in the early days, where the board of directors would supposedly all share a joint or two before meetings. Thus when Stu Galley started to roll a cigarette in front of him that first day he thought the worst — but no, it was just tobacco. Palace went from the interview to the home of a friend of his in Brooklyn who had a computer and some of Infocom’s games to try to figure out what this company who might be about to hire him was actually all about.

If Palace didn’t quite know what Infocom wanted from him, Infocom didn’t really know either. They felt they needed someone who could serve as a sort of professional liaison for each game, to stand at the hub of the wheel and coordinate among the Imps that wrote the games, the Micro Group that deployed them onto the target platforms, G/R Copy and internal marketing who packaged and advertised them, and the logistics folks who scheduled them for release and got them to the customers. What they were really looking for was a producer, but they didn’t know that; in these early days of the games industry that role had yet to be defined. Then Mike Berlyn piped up to say that the sorts of things they were talking about sort of seemed like the stuff his editor used to do for him back when he was writing novels instead of games. And so Infocom was suddenly advertising for what had to be the strangest “editor” job that was ever offered. And Palace, who didn’t even own a computer, just stumbled into it. Infocom hired him to start that April.

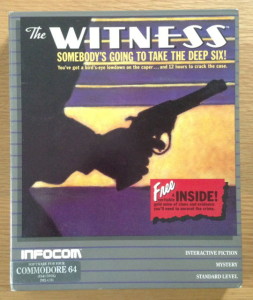

Realizing he had lots of catching up to do if he even wanted to understand most of the conversations taking place around him, Palace took to returning to the office in the evening with his wife and some Chinese food to catch up on the Infocom back catalog. Soon he bought a used Apple IIe from Mike Berlyn so they could play at home. When his parents had trouble grasping just what it was he was now doing for a living, he pulled out The Witness to show them, Infocom-style — interactively. They then spent a fun evening trying to figure out who killed Freeman Linder.

Like Stu Galley, who also initially had no big interest in this whole adventure-game thing, Palace became one of the most idealistic Infocom employees about the potential and the worth of the work they were doing. That idealism, combined with his background in writing and publishing, proved to be invaluable. One might even say that Palace became the final piece of the Infocom puzzle. He filled his producer’s role admirably, but, perhaps even more importantly, he pushed everyone to take their craft that much more seriously. Palace served as a buffer between those ever-opposed forces of Creative and Business, making sure no game was released before its time. Indeed, he gently prodded the Imps to spend that little bit of extra time and effort making their worlds believable, making sure their stories made sense, and, most of all, polishing their prose. Steve Meretzky gave Palace one of his few public acknowledgements in the Leather Goddesses of Phobos hint book, using words which speak not just to the roles he played but to the way he was valued — even beloved — by the Imps for the way he went about it: “Thanks to Jon Palace for a host of things, but especially for his help in ‘sensualizing’ the text, and for being a front-line defense against scheming marketeers.” When Jason Scott began planning interviews for his Get Lamp film almost twenty years after Infocom’s demise, the former Imps were almost unanimous in naming Palace as the greatest of all the unknown contributors to Infocom’s success. In his own low-key way he was as important to all of the great work that came out of the company between 1984 and 1988 as anyone whose name actually appeared on the boxes. He became a key reason that the Imps refused to abandon their sense of craft and artistic integrity even as the circumstances around them, as I shall soon have to recount in all too much detail, made that more and more difficult.

But we don’t have to talk about that just yet. We’re just in 1984, after all, a very successful sales year for Infocom — in fact, the biggest such they would ever enjoy, the very apex of the bell curve that is their commercial history. It was also a year of consolidation and systemization; it was the year of the gray box.

Infocom’s trademark lavish packaging had been something of a sore point with retailers for some time now. Everyone loved creations like the Starcross saucer and the Suspended mask when the games were new; many owners hung the former from the ceiling all around their stores. The problem came after the initial hype had died down, when the games became catalog items to be stocked in quantities of just one or two and shelved toward the back of the store. Here the Starcross saucer tended to roll onto the floor, if it would fit on the rack at all, while the Suspended mask ran the risk of getting squashed flat between the other games on the rack. Moreover, such oddball injection-molded packages were expensive to make, particularly after they became catalog items and the quantities being made in each batch dropped dramatically. Infocom had thus already begun to scale things back; after Suspended all of the games were released in relatively more modest, conventional boxes. But even those were all essentially one-offs. By 1984 Infocom’s games ranged from the minimalist blister packs of the Zork games to the absurd flamboyance of Starcross and Suspended, with everything else somewhere in between. Any given game may have been beautifully packaged, but together on a shelf they kind of looked like a jumbled mess. You’d be hard pressed to realize they were all products of the same company. And, as dealers never ceased to tell them, this jumble was wasting space on the shelves that could be given over to stocking more Infocom games. Something needed to be done.

Infocom therefore did something they rarely did (and arguably could have done more often): they looked at what the competition was doing. The model for packaging in the industry at this time was the folio-style package used by Electronic Arts. It was a consistent look that immediately marked a game as a product of EA. Being deliberately evocative of a record sleeve, it also conjured exactly the image that EA, that would-be purveyor of hip, sophisticated entertainment crafted by a new generation of “electronic artists,” wanted to present to the world. Retailers absolutely loved it: it was slim and compact but still attractive, as easy to shelve onto racks spine-outward by the dozen as it was to open up, unfold, and stick in a display window. Infocom, driven particularly by head of marketing Mike Dornbrook, decided they needed something like that. What they came up with in association with the ever-essential G/R Copy was a veritable masterstroke.

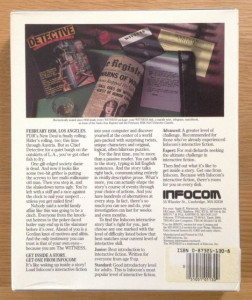

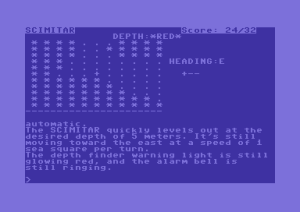

The box is, not coincidentally, of about the dimensions and thickness of a typical hardcover novel. With the era of bookware in full bloom and Infocom’s games now showing up on more and more bookstore racks thanks to a distribution deal with Addison Wesley, the packaging and all of its associated rhetoric emphasizes the game’s literary qualities. Said emphasis extends right down to the contents of the disk; you type, for instance, “LOAD ‘STORY’,8” to start a game on the Commodore 64. The cover, meanwhile, prominently displays Infocom’s official new name for their works: not “adventure game,” not “text adventure,” but “interactive fiction.” It also shows where the game fits in a matrix of genres (consisting in the beginning of “Fantasy,” “Science Fiction,” “Tales of Adventure,” and “Mystery”) and difficulties (“Interactive Fiction Junior,” “Standard,” “Advanced,” and “Expert”).

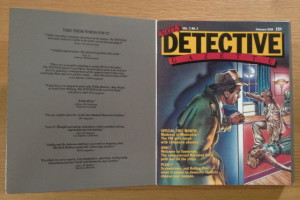

The cover of the box flips open like a book for easy in-store browsing; it isn’t shrink-wrapped. Inside the left cover is a set of testimonials from happy customers. Most are the sort of thing you would expect, but, Infocom being Infocom, one or two bizarre remarks or complete non sequiturs were usually included in every game.

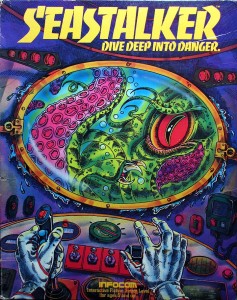

A bound-in booklet — called in-house the “browsie” because it was aimed as much at potential customers browsing in the store as at those same customers after they had brought the game home — begins with something to set the fictional stage: an issue of National Detective Gazette, a Stellar Patrol brochure, “The Great Underground Empire: A History.” The second half of the browsie is given over to a conventional instruction manual that incorporates everything Infocom had learned over the previous several years about teaching people how to play their games as quickly and painlessly as possible. The “Sample Transcript and Map,” an innovation which first appeared in Seastalker, the final pre-gray-box release, is a particular stroke of genius. It shows by example how to play and how to make a map via a fictional game made up just for the occasion by Infocom. Each title got its own sample transcript which takes place in a similar environment to the one found on the disk and demonstrates that title’s general style of play.

The new scheme was welcome not least in that it let Infocom separate each game’s fictional context from technical instructions on how to work it. Previously they had blended everything together, a conceit that must have seemed clever when they first did it for Deadline but that had grown very strained by 1984. (The original version of The Witness is a typical example. Its National Detective Gazette includes an article titled “Investigative Machines of the Future!” explaining this “Computer” that in the “early part of the next millennium” will be “the most important tool of the detective’s trade.”)

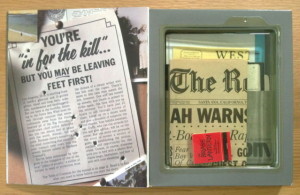

After the browsie comes the portion of the package that is sealed, containing the various physical feelies as well the game disk itself, all peeking enticingly through a clear plastic cover for the benefit of in-store browsers.

And finally there’s the back side of the box, which has the expected flavor text for the game as well as a shot of all the feelies on display. Then comes some standard text, a sort of mission statement for Infocom interactive fiction (“It’s like waking up inside a story!”; “You’re more than a passive reader!”), along with an explanation of the difficulty levels.

Converting the entire catalog to the new format was a huge task which consumed lots of resources during the first half of 1984. While much of the material that would go into the gray boxes already existed, it had to undergo considerable reworking in virtually every case to fit into the new format. Just untangling the fictional context from the technical instructions was a time-consuming, delicate task. And much had to be written from scratch, such as a suitably clever sample transcript for every single game. The three Zork games, which had previously shipped in blister packs containing only a disk and a slim manual telling how to play, demanded the most effort of all; a browsie and set of feelies that would be evocative enough to stand alongside those in the other games had to be designed for each from scratch.

Brilliant as the new packaging was, there was some inevitable sadness at Infocom over the loss of the likes of the Starcross saucer and the Suspended mask and a certain individual personality for each title that the old “anything goes” approach to packaging had represented. Certainly compromises — sometimes painful ones — had to be made. Steve Meretzky was particularly broken up about the loss of the infotater from the Sorcerer package; it was just too big to fit into the gray-box feelie tray, and so had to be replaced with a simple booklet.

The matrix of genres and difficulties was as useful to Infocom internally as it was to their customers. A diagram showing its current state — i.e., what current and upcoming games slotted in where — could generally be found on a whiteboard in the marketing department. This allowed them, as Jon Palace puts it, to “figure out where the holes were” in the current product line and not “put too many in one place.” In deciding what games to approve for development, big emphasis would be given to keeping the matrix balanced, making sure there were games for all fictional interests and all experience levels. After the beginning of the gray-box era you wouldn’t see unbalanced stretches like the one in late 1982 and early 1983 when three of five titles were science fiction — or for that matter Seastalker and Cutthroats, two titles released back to back just as the matrix was coming into force that were both nautical “Tales of Adventure” set in contemporary times.

The genres on the matrix were always much more defensible than the difficulty levels, which often seemed like little more than wishful thinking driven by the slot marketing would like for any given game to occupy. Zork I, while not quite so objectionable as Zork II, was a huge game with some very questionable puzzles that never would have made it into a later Infocom game. Just mapping its huge geography full of willfully inconsistent room connections could require hours of patient, dogged work with graph paper, pencil, and eraser. Yet Zork I also remained Infocom’s biggest seller by a country mile, selling more copies every year it remained on the market; it sold more than 150,000 copies in 1984 alone, an absolutely huge figure for the era and enough to account for more then 20% of Infocom’s total sales for the year. Many computer dealers still seemed to regard Zork I as an essential accessory to be taken home by the customer along with printer paper and some blank disks every time they sold a new computer system. Infocom simply couldn’t drive such customers away with an “Advanced” or “Expert” label on this evergreen. So, Zork I became a “Standard”-level game. Similar concerns would soon lead to Infocom’s adaptation of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the cruelest game they had released since the days of Zork, Deadline, and Suspended but also one with a potential mass appeal like nothing they had done before, also being given the “Standard” label.

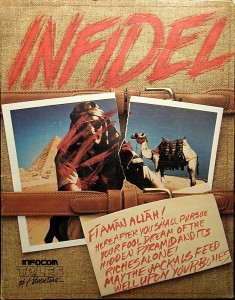

Stranger, because less explicable, were the difficulty levels bestowed on other games. Starcross, by no means a trivial challenge but one full of logical puzzles in a relatively consistent environment, was nevertheless an “Expert” game, while Infidel, the most straightforward game Infocom had yet produced outside of the deliberately easy Seastalker, became an “Advanced” game. One can only presume that, with the “Standard”-level Cutthroats about to be released and Seastalker in the “Junior” slot, Infidel fit the matrix better as an “Advanced”-level “Tale of Adventure.” Ditto for Starcross with Planetfall and the forthcoming Hitchhiker’s, both of which were already crowded into the “Standard” science-fiction slot. In the end marketing likely did themselves few favors with this sort of wishful thinking. Any new player who bought Zork I or Hitchhiker’s and was completely baffled, then looked at the box to see this was only “Standard”-level interactive fiction, “a good introductory level for adults”… well, she probably wasn’t likely to buy another. No one likes to feel stupid. If Infocom couldn’t make the difficulty levels accurate (and, as noted, there were indeed legitimate commercial concerns that made this problematic), they would have been better served to leave them off entirely.

Be that as it may, times in general were good. Infocom was the main reason for the bookware craze that was the hot new trend in entertainment software in 1984, even though, ironically, their own first book adaptation would only appear at the end of the year in the form of Hitchhiker’s. And their reputation extended far beyond the software industry. They were in Mike Berlyn’s words “intellectual rock stars”; it seemed everyone wanted a piece of them. Christopher Cerf, a big wheel with the Children’s Television Workshop, took a few of them out to meet with Jim Henson to discuss creative opportunities. George Romero of horror-movie fame asked them about movie rights to Zork. Timothy Leary wrote Berlyn a gushing letter about Suspended, saying it had “changed his life” and revealed to him the potential of computers with its portrayal of split consciousness. He later visited Infocom in person to discuss a collaboration. He envisioned a “personality” that would live in the computer, observe what you did and how you liked to do it, and adjust the experience of using the computer accordingly. None of these talks ultimately came to anything, but for this bunch of hackers and refugees from academia, who had mostly been kids or teens when Night of the Living Dead was provoking shock and outrage at the Saturday matinees and the Moody Blues were serenading Leary on the radio, it was heady stuff indeed. (Leary did eventually find a willing collaborator in Electronic Arts. Timothy Leary’s Mind Mirror — “Tune in, turn on, boot up” — became one of the strangest products that company would ever release, one that would never have seen the light of day outside of the experimental mid-1980s.)

And then, to cap off a crazy year, Simon & Schuster came calling waving tens of millions in their faces.

The story of the Simon & Schuster negotiation, only recently fully known thanks to the Get Lamp project, begins with one of the most important and controversial figures in publishing of the late twentieth century: Richard E. Snyder. Snyder started at Simon & Schuster in 1960, and had risen to vice president by the time the massive conglomerate Gulf and Western (or, as Mel Brooks dubbed them in Silent Movie, Engulf and Devour) acquired the company in 1975; his biggest claim to fame during these early years was perhaps giving Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward the title for All the President’s Men. After years of chafing against the hidebound practices of Simon & Schuster’s original management, he at last got the chance he had been dreaming of from Gulf and Western, who made him president in 1975 and CEO in 1978. Determined to wrench the company out of the past and into the modern world of media and entertainment, Snyder unabashedly pursued celebrities and big, commercial projects whilst building a reputation as the meanest man in his field, the barbarian at the gate of the tweedy, traditional world of publishing. He took a special delight in firing people, setting aside a room for the purpose that came to be called the “executive departure lounge.” His reputation spread far and wide; he made Fortune magazine’s list of “America’s Toughest Bosses” in 1984 in an article which compared him to the Ayatollah Khomeini — only Snyder had more hostages, Fortune wrote, in the form of an entire company which supposedly quaked in fear of him. He also became known for, in the words of Washington Post columnist Jonathan Yardley, “his assiduous accumulation of executive perquisites unmatched since the heyday of William Randolph Hearst, if not Croesus.” But he got results: in fifteen years he took Simon & Schuster from a $40-million business to a $2-billion business, from a modest trade publisher to the biggest, most diversified publisher in the world.

Much of that growth was fueled by aggressive acquisitions that let Simon & Schuster capitalize on any hot trend that came down the pop-culture pipe. Thus they were only being true to form when they began nosing around Infocom, kicking the tires as it were, as early as late 1983. They were eager to point out (in Mike Dornbrook’s words) “all the wonderful things they could do” for Infocom, which included among other things the chance to make games in the Star Trek universe; Paramount Pictures was also a subsidiary of Gulf and Western, and Simon & Schuster already published the Star Trek line of novels on their Pocket Books imprint. Snyder got personally involved in the latter half of 1984. Like any good publisher, he talked often to people in the bookstore trade. Waldenbooks, the biggest chain in the United States at the time, continued to mention often how well they were doing with this company called Infocom and this thing they made called interactive fiction.

And so Snyder, who could be charming as hell when he wanted to be, decided to try to make a deal personally. He invited Marc Blank and Mike Dornbrook to visit him in his executive suite near the top of a skyscraper in Rockefeller Center. It made, to say the least, quite the contrast to Infocom’s comfortable little home on Wheeler Street back in Cambridge. Dornbrook recalls marveling at the restroom, which “used gold in ways I had never thought of using gold.” The three had lunch in Snyder’s executive dining room at a table big enough to seat thirty — Dover sole, prepared by Snyder’s personal chef and served by three liveried attendants. Snyder stroked them like a master. Dornbrook:

Marc said, “Mike, why don’t you tell Mr. Snyder a little bit about InvisiClues?”

So I described what I’d done. I mentioned the selling price and how many had sold. By that point, late 1984, we’d sold over half a million — the Zork I InvisiClues book alone had sold something like 200,000 copies.

Synder said, “You’ve sold 200,000 copies at $9.95? That’s trade-paperback prices! Do you realize you’re one of the bestselling authors on the planet?”

I said, “What?”

Snyder said, “In terms of dollars you’re at Stephen King level!”

I was totally blown away.

Shortly after, Snyder sent a Gulf and Western acquisitions negotiator and the Simon & Schuster manager he proposed to have oversee Infocom to visit them in Cambridge. They arrived in a limousine to take Blank, Stu Galley, and Al Vezza (who had replaced Joel Berez as planned as Infocom’s CEO in January of 1984) to another opulent lunch. When they got down to specifics at last and made their offer, it was extraordinary: $28 million. To put this in context, understand that Infocom’s board had recently estimated the company’s value at perhaps $10 million, $12 million at the outside.

Yet feelings were mixed on Infocom’s side. While Blank and Joel Berez were reportedly very interested, Galley had taken an immediate dislike to the would-be overseer, feeling certain within minutes that he “didn’t understand” Infocom and never would. And Vezza couldn’t help but feel that if a corporate titan like Snyder, who, say what you would about him, didn’t get where he was by being stupid, was offering that kind of money then in the big picture Infocom must be worth much more. The negotiator’s response to his hemming and hawing only reinforced the impression. In Dornbrook’s recollection, he said, “Look, if it’s just a matter of a few million dollars, I don’t care, I’ll pay you more. But are you or are you not interested in selling?” Still unable to elicit a clear answer to that question, he decided that Vezza was not. Simon & Schuster ended up starting a brief-lived interactive division of their own in lieu of Infocom. Their most high-profile releases became, yes, a few Star Trek adventures.

In light of the course Infocom’s fortunes would soon take, both the people who were there at the time and mere interested parties like you and me will inevitably continue to second-guess the decision — or, perhaps better said, non-decision — for years to come. Jon Palace notes, probably correctly, that there was a certain amount of hubris in Infocom’s rejection of Snyder’s millions, that they couldn’t help but let some of the glowing press go to their heads and really did suspect that Simon & Schuster might just be getting them too cheap at a mere three times their valuation by the company accountants. And certainly interactive-fiction fans who feel the genre died (commercially) far too young are always looking for viable counter-factuals that keep Infocom alive and thriving into the 1990s and hopefully beyond.

Still, it’s hard for me to see this deal turning out all that well for Infocom in the end. Friction almost always results when a small, creative company is bought by, as Dave Lebling describes Simon & Schuster, “a giant soulless corporation.” When the bookware craze died down, as it seems it must whether Infocom was acquired or not, Infocom would have been just an artifact of a trend, one of many that hadn’t taken off quite like Simon & Schuster hoped. You win some and you lose some in business, after all. Nor was Snyder, as famous in the business community as he was hated by Simon & Schuster’s management class for his micromanaging instinct, exactly known as a patient man. A Simon & Schuster Infocom may very well have given us fewer works than did the eventual Activision Infocom; certainly the much larger Simon & Schuster was much more likely to write off an acquisition quickly as a failed bet and move on than was Activision. Even the former Imps, most of whom would have done very well financially by the acquisition, will mostly wryly admit that they look on the Simon & Schuster negotiation wistfully not so much as the potential enabler of many more years of fruitful creativity as an opportunity to cash out on all their hard work, to walk away from Infocom in the end with something more than the salary they’d earned over the years to show for their entrepreneurial efforts. That’s not a feeling we should begrudge them; I’m sure every one of us with mortgages and car payments would look back the same way. But it’s also a long way from the more idealistic what-might-have-beens that tempt us.

And there was always an elephant in the room as the board discussed the merits of Simon & Schuster’s offer: the Business Products division and the Cornerstone database. What had started as a two-man research project in October of 1982 and been officially approved as a viable endeavor ten months later had, since Al Vezza’s arrival as CEO in January of 1984, become Infocom’s strategic priority, consuming all the money the games generated and millions more that they had to acquire through bank loans. Simon & Schuster had no interest in business software, and would have been more than happy just to take the games division for their $30 million. Problem was, Infocom needed the ongoing revenue from the games division to keep Business Products going. Somehow funneling some or all of Simon & Schuster’s millions back into a remade Infocom-as-business-developer would involve tricky, time-consuming accounting shenanigans for which Vezza just didn’t feel he had time; Cornerstone was now entering the final, expensive crunch time, with a planned release in January of 1985. And Cornerstone was the dream of Vezza and at least a few of the other old timers, the reason they had founded Infocom in the first place. If becoming a success in business software is a more prosaic dream than that of inventing a new way of sharing stories, well, hey, it takes the prosaic as well as the poetic to make a world. Who are we to judge?

But the full story of Cornerstone is a story for another article. For now let’s just note that, despite tensions and conflicts that inevitably arose from packing a bunch of game and business developers together in the same increasingly cramped office, things in the big picture were still looking pretty great to just about everyone as they celebrated Christmas 1984. They had sold about 725,000 games that year worth $10 million, up from 450,000 and $6 million the previous year. They were so successful in their field that a whole genre of bookware had sprung up to try to capture some of their success, that their company name risked becoming synonomous, Kleenex-style, with the adventure game — or okay, if you like, “interactive fiction” — itself. And they had some of the more interesting people on the planet coming to them to propose collaborations. Speaking of which: their collaboration with Douglas Adams on the Hitchhiker’s game had sold some 60,000 copies in its first six weeks or so, a pace out of the gate that none of their earlier releases had even approached. If anything had frustrated Infocom over the last couple of years, it had been their inability to field a title that would break beyond the label of just “very successful” to become a phenomenon like Zork I, which at four years old still outsold any of their other games by a factor of two and had in fact just had its biggest sales year ever. Now it looked at last like they had another Zork. With the next Hitchhiker’s game expected by next Christmas, 1985’s game sales were estimated — very conservatively, they thought — as likely to reach at least $13 million. Add to that the at least $5 million or so they expected from the first year of Cornerstone sales, and it looked likely to be one hell of a year.

Granted, a sober-minded accountant or financial analyst might have looked at things less optimistically. She might have noted that Infocom had managed to maintain their upward sales trajectory even as the home-computer industry in general suffered a disappointing year of slowing hardware and software sales, failed platform introductions, shrinking or disappearing magazines, and a mainstream media that was suddenly as cynical about home computers as they had been ecstatic about them a year before. It was of course great that Infocom was so far bucking the trends — but would it continue? She also might have wondered why this company that was so ridiculously good and successful at this one thing was so determined to branch out into this other thing. After all, every business student learned that a small company should do one thing and do it well, that trying to do too much too soon was usually a fatal mistake. And, most worrisome of all, she might have noted that Infocom’s board had, wittingly or unwittingly, effectively bet the company on this new thing by going millions into debt to finance it. There was no Plan B if Infocom didn’t become successful in business products like they were in games. Indeed, one fact must have glared out at her as soon as she peeked at the books: thanks to Business Products, Infocom had managed to lose $2.4 million in 1984 despite sales increases of some 67%.

But, Vezza and the board would have replied, that was just temporary, just the money Infocom had to spend to make even more money in an industry that dwarfed the one they currently all but dominated. Cornerstone was shaping up to be a great product. It couldn’t fail.

Could it?

(As usual for my Infocom pieces, my secret weapons for this article were Jason Scott’s Get Lamp project materials. Thanks again for sharing, Jason!)