(This article doesn’t spoil individual puzzle solutions, but does thoroughly spoil the ending of Infidel. Read on at your own risk!)

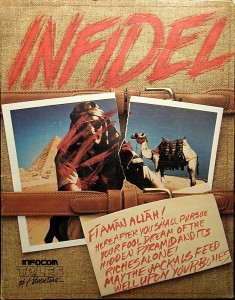

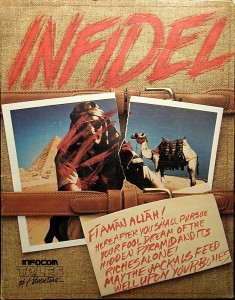

In the spring of 1983, having released successful games in the fantasy, science fiction, and mystery genres, the Imps of Infocom sat down to ask each other a question they would repeat quite a number of times over the coming years: what remaining literary genres might make a good basis for a game? Mike Berlyn, who had just finished up Suspended, suggested, appropriately enough for an adventure game, the genre of adventure fiction, those tales of manly men braving exotic dangers in exotic locations which has its roots in the likes of H. Rider Haggard and Arthur Conan Doyle and reached its peak, like the mystery, in the 1930s, when pulpy stories filled the dime store shelves and the cinema screens to be consumed by a public eager for escape from economic depression and the looming threat of another world war. It sounded like a great fit to the Imps. The genre was even undergoing something of a commercial revival; Raiders of the Lost Ark had prompted a new interest by Hollywood and booksellers in classic adventure fiction. Somewhat to his chagrin, Berlyn was promptly assigned to write the first game in the new Tales of Adventure line, which the Imps agreed would have the player exploring a heretofore undiscovered Egyptian pyramid found buried under the sands of the Sahara. And so Pyramid, eventually to be renamed Infidel by the ever-helpful folks at G/R Copy, became Berlyn’s second project for Infocom.

It’s not hard to understand why Infocom chose pyramid-delving as the subject of the first Tale of Adventure. The exploration of a deserted environment filled with mechanical traps, tricks, and puzzles is a natural for an adventure game. It’s actually hard to think of a scenario more able to maximize the medium’s strengths and minimize its limitations. Thus quite a few early adventure authors discovered a latent interest in Egyptian archaeology. Greg Hassett, who at just twelve years old wrote and sold King Tut’s Tomb Adventure for the TRS-80 in 1979, was likely the first, but Scott Adams (Pyramid of Doom) and an official Radio Shack game (Pyramid 2000) weren’t far behind, as were various others. Somewhat allaying any concerns about a hackneyed premise was Infocom’s commitment to doing ancient Egypt right, with their expected polished writing and technology, and with at least a strong nod in the direction of historical accuracy. To help with this latter, Berlyn, no Egyptologist himself, trekked down to nearby Harvard University and recruited one Patricia Fogleman, a graduate student studying ancient Egypt. She helped him with his Egyptian mythology and with the design of the pyramid itself, which are of course largely one and the same thing.

Still, the game they came up with is mechanically almost shockingly unambitious, a double surprise considering it came from the designer responsible for Suspended, a game which morphed and stretched the ZIL development system more than any game Infocom released before or since. You wake up at the beginning of Infidel in your deserted desert camp. The guides and workers who came out here with you have conveniently (for Berlyn, that is) drugged you and split, leaving you all alone to find the pyramid and explore it. With the exception only of a plane which flies overhead at the beginning to drop a vital piece of equipment and some crocodiles which dwell (thankfully) inaccessibly on the other side of the Nile, Infidel is absolutely devoid of any life beyond your own, the only Infocom game about which that can be said. There is also none of the dynamism that marked Infocom’s other games of the period. After the plane flies away Infidel‘s environment is as static as it is deserted — just a set of locations to map and explore and a series of mechanical puzzles to solve. The only notable technical innovation is the inclusion of a knapsack that you can use to carry far more objects than your hands alone would allow. Similar carry-alls eventually started appearing in other adventures as a way to preserve some semblance of realism in not allowing you to carry a ridiculous number of items in your hands while bypassing the tedium of strict inventory limits. Thankfully, they were mostly more painless to use than this one is; here you have to remove the knapsack and set it down, then manually insert or remove items.

The most interesting of the puzzles is a sort of ongoing code-breaking exercise. You find throughout the pyramid hieroglyphs scratched onto the walls and other places. Each symbol — drawn using various dashes, slashes, asterisks, and exclamation points — corresponds directly to an English word in a way that must have horrified Fogleman or any student of language. The feelies provide translations of a handful of these to start you off, but after that it’s up to you to piece together the meanings by collecting the full set on notepaper and trying to determine what means what using contextual clues. Disappointingly or gratifyingly, depending on your tolerance and talent for such exercises, this meta-puzzle is largely optional. The hieroglyphs do give hints as well as additional tidbits about the meanings behind the wonders you encounter, but the game is mostly straightforward enough that the hints aren’t necessary. In the one exception to this rule the translation is quite a trivial exercise. Indeed, solving Infidel is not difficult at all. Players experienced with Infocom’s adventures are likely to march through with few problems, waiting all the while for the other shoe to drop and for this thing to get hard. It never really does.

So, were that all there was to Infidel we would have a competently crafted, solidly written game, but one that stands out as oddly, painfully slight in comparison to its stablemates in the Infocom canon, and this would be quite a short article. However, Infidel turned out to be as conceptually groundbreaking as it is mechanically traditional, leaving angry players and broiling controversy in its wake.

Infidel‘s story — its real story, that is, not the mechanics of collecting water, operating navigation boxes, and opening doors — lives mostly within its feelies. In them Berlyn sought to characterize his protagonist to a degree rivaled amongst previous adventure games only by Planetfall. But while that game had you playing a harmless schlub who spent his days swabbing decks and bitching about his superior officer, Infidel casts you as someone less harmless: a frustrated American treasure hunter with an unethical streak as wide as your thirst for money and glory. Your diary tells how you were contacted by a Miss Ellingsworth, an old woman who believes her archaeologist father located something big in the Egyptian desert back in the 1920s. You choose not to report her story to your boss, a well-known, hyper-competent treasure hunter named Craige, but rather to secretly mount an expedition of your own, deceiving Miss Ellingsworth into believing that you’re working in partnership with Craige, the person she really wanted for this quest. Once in Egypt you mismanage everything about your under-capitalized expedition horribly, breaking a vital piece of equipment needed to find the pyramid and mistreating your team of guides and workers. That’s how you come to wake up alone in your tent when the game proper finally begins.

The game proper originally did little to integrate the character described in the feelies with the one you actually control in the game. It occasionally, just occasionally, adapts a scolding or hectoring tone: the opening text describes how you “stupidly” tried to make your crew work on a holy day; examining some thickets near your camp brings the response that they are “just about as yielding as you were with your helpers.” Even less frequently do you get a glimpse of your character’s personality, as when you “sneer” at the “idiots” who didn’t believe in you when you find the pyramid at last. Yet the game that Infocom’s testers received otherwise played like a greedy treasure hunt to warm the protagonist’s heart, climaxing with your penetrating to the innermost vault of the pyramid and coming out with the fame and fortune of which you had dreamed. The testers, obviously a perceptive and sensitive lot, complained about the thematic dissonance. Berlyn took their concerns to heart, and decided to revise the ending to make a major statement.

Much as I enjoy the likes of King Solomon’s Mines and The Lost World, it’s hard today to overlook the racism and cultural imperialism in classic adventure fiction. Invariably in these tales strong Christian white men end up pitted against black, brown, yellow, or red savages, winning out in the end and carrying the spoils of victory back home to a civilization that can make proper use of them. Maybe if the savages are lucky the white men then return to organize and lead their societies for them. It’s the White Man’s Burden writ large, colonialism at its ugliest: kill them and take their stuff. More trivially, the second part of this dictum is also the guiding ethic of old-school adventure games, sometimes without the killing but not always; CRPGs were generally lumped in with adventures as a variant of the same basic thing during this era. Dave Lebling and Marc Blank had already had their fun with the amorality and the absurdities of adventure games in Enchanter by inserting the stupid magpie adventurer from Zork to let us view him from a different perspective. Now Berlyn decided to treat the subject in a much more serious way, making of Infidel a sort of morality tale. He would invert expectations in a downright postmodern way, pointing out the ugly underbelly of traditional adventure stories from within a traditional adventure story, the moral vacuum of old-school adventure games from within one of the most old-school games Infocom would create post-Zork trilogy. Derrida would have been proud. Speaking to Jason Scott, Berlyn noted that Infidel was the first adventure game that “said who you were, why you were there, then slapped you across the face for it. How many times can you walk through a dungeon and steal things and take them with you and plunder for treasure and not get slapped around for it? Well, Infidel was the end of that.” No wonder lots of people got upset.

The following text, more shocking even than the death of Floyd, is what players read in disbelief after they entered the final command and sat back to savor the finishing of another adventure game:

>open sarcophagus

You lift the cover with great care, and in an instant you see all your dreams come true. The interior of the sarcophagus is lined with gold, inset with jewels, glistening in your torchlight. The riches and their dazzling beauty overwhelm you. You take a deep breath, amazed that all of this is yours. You tremble with excitement, then realize the ground beneath your feet is trembling, too.

As a knife cuts through butter, this realization cuts through your mind, makes your hands shake and cold sweat appear on your forehead. The Burial Chamber is collapsing, the walls closing in. You will never get out of this pyramid alive. You earned this treasure. But it cost you your life.

And as you sit there, gazing into the glistening wealth of the inner sarcophagus, you can't help but feel a little empty, a little foolish. If someone were on the other side of the quickly-collapsing wall, they could have dug you out. If only you'd treated the workers better. If only you'd cut Craige in on the find. If only you'd hired a reliable guide.

Well, someday, someone will discover your bones here. And then you will get your fame.

It’s an ugly, even horrifying conclusion; lest there be any doubt, understand that you have just been buried alive. It’s also breathtaking in its audacity, roughly equivalent to releasing an Indiana Jones movie in which Indy is a smirking jerk who gets everyone killed in the end. This sort of thing is not what people expect from their Tales of Adventure. Infocom rarely did anything without a great deal of deliberation, and releasing Infidel with an ending like this one was no exception. Marketing was, understandably, very concerned, but the Imps, feeling their oats more and more in the wake of all of the attention they had been receiving from the world of letters, felt strongly that it was the right “literary” decision. The game turned out to be, predictably enough, very polarizing; Berlyn says he received more love mail and more hate mail over this game than anything else he has ever done.

The most prominent of the naysayers was Computer Gaming World‘s adventure-game specialist Scorpia, who was becoming an increasingly respected voice amongst fans through her articles in the magazine, her presence on the early online service CompuServe (where she ran a discussion group dedicated to adventuring), and a hints-by-post system she ran out of a local PO Box. Scorpia was normally an unabashed lover of Infocom, dedicating a full column in CGW to most Infocom games shortly after their release. On the theory that it’s better not to say anything if you can’t say something nice, however, she never gave Infidel so much as a mention in print. But never fear, she made her displeasure known online and to Berlyn personally, to such an extent that when he was invited to an online chat with Scorpia and her group on CompuServe he sarcastically mentioned the game as her “fave rave.” Things got somewhat chippy later on:

Scorpia: Now, I did not like Infidel. I did not like the premise of the story. I did not like the main character. I did not like the ending. I felt it was a poor choice to have a character like that in an Infocom game, since after all, regardless of the main character in the story, *I* am the one who is really playing the game, really solving the puzzles. The character is merely a shell, and after going thru the game, I resent getting killed.

Berlyn: What do you want me to do? I can’t make you like something you don’t like. I can’t make you appreciate something that you don’t think is there. I will tell you this, though, you are being very narrow-minded about what you think an Infocom game is. It doesn’t HAVE to be the way you said and you don’t have to think that in *EVERY* game you play, that YOU’re the main character. A question for you: yes or no, Scorp, have you ever read a book, seen a TV program, seen a movie where the main character wasn’t someone you liked, was someone you’d rather not be?

Scorpia: Certainly.

Berlyn: Okay. Then that’s fair. If you look at these games as shells for you to occupy and nothing more, like an RPG, then you’re missing the experience, or at least part of the potential experience. If you had read the journal and the letter beforehand I would have hoped you would have understood just what was going on in the game — who you were, why you were playing that kind

of character. Adventures are so STERILE! That’s the word. And I want very much to make them an unsterile experience. It’s what I work for and it’s my goal. Otherwise, why not just read Tom Swifts and Nancy Drews and the Hardy Boys?

Oct: May I comment on the Infidel protagonist?

Scorpia: Go ahead, Oct.

Oct: As far as I know (through about 8 games that I’ve played) Infidel is the only one that creates a role (in the sense of a personality) for the protagonist-player. A worthwhile experiment, but I somewhat agree with Scorp that it wasn’t completely successful. The problem is that a game provides a simulated world for the protagonist and just as in life the player must do intelligent things to “succeed” (in the sense of surviving, making progress). If the role includes stupidity or bullheadedness, then the player will not make progress, which in the context of the game means not being able to continue playing. Further, the excellence of the Infocom games is in their world-simulation, but simulating a personality for the *player* is not really provided for in the basic design, the fundamental interaction between game and player. I feel I’ve not articulated too well, but there’s a point in there somewhere!

Berlyn: I never claimed the protagonist works in Infidel. I only claim that it had to be tried and so it was. There are a lot of personal reasons for my disgust (I hate the game, myself) over the whole Infidel project, but none of it had to do with the protagonist/ending problems the game has. Let me put it to you this way: Like anyone who produces things or provides a service — you put it out there and you take a chance. You wait for the smoke to clear and then you listen to people like yourselves talking about whether the experiment succeeded or failed and I could have told you it might have gone either way when I was writing it. There was just no way to know.

Oct: I think I can better summarize the problem with roles, now. Ok?

Berlyn: Go ahead, Oct.

Oct: If you give the player a role, as in the set-up (the journal) and he/she wants to view him/herself that way, ok. The problem is that the only way that can be effectively represented is in how the other actors in the game view/respond to the player. If you try to implement it by saying “You now do this,” you’ve violated a basic premise, namely that *I* decide what I want to do (whether in a role or otherwise). “You now do this” just isn’t part of the game!

Berlyn: I agree. Some of the problems I faced in this game are what kind of a human being would even WANT to ransack a national shrine like a pyramid? And once I asked myself that question, I was sunk and there was no turning back. It wasn’t even a game I wanted to write. I got off on it by putting in all the weirdness, the ‘glyphs, the mirages, the descriptions but I’ve learned from the experience. Marc once said to me, “This is the only business where you get to experiment and people really give you feedback.” He was right. And I appreciate it.

I find this discussion fascinating because it gets to the heart of what a narrative-oriented game is and what it can be, grappling with contradictions that still obsess us today. When you boot an adventure are you effectively still yourself, reacting as you would if transported into that world? Or is an adventure really a form of improvisatory theater, in which you put yourself into the shoes of a protagonist who is not you and try to play the role and experience that person’s story in good faith? Or consider a related question: is an adventure game a way of creating your own story or simply an unusually immersive, interactive way of experiencing a story? If you come down on the former side, you will likely see the likes of Floyd’s death in Planetfall and Infidel‘s ugly ending as little more than cheap parlor tricks intended to elicit an unearned emotional response. If you come down on the latter, you will likely reply that such “cheap parlor tricks” are exactly what literature has always done. (It’s interesting to note that these two seminal moments came in the two Infocom games released to date that were the most novel-like, with the most strongly characterized protagonists.) Yet if you’re honest you must also ask yourself whether a text adventure, with its odd, granular obsession with the details of what you are carrying and eating and wearing and where your character is standing in the world at any given moment, is a medium capable of delivering a truly theatrical — or, if you like, a literary — experience. Tellingly, all of the work of setting up the shocking ending to Infidel is done in the feelies. By the time you begin the game proper your fate is sealed; all that remains are the logistical details at which text adventures excel.

Early games had been so primitive in both their technology and their writing that there was little room for such questions, but now, with Infocom advancing the state of the art so rapidly, they loomed large, both within Infocom (where lengthy, spirited discussions on the matter went on constantly) and, as we’ve just seen, among their fans. The lesson that Berlyn claims they took from the reaction to Infidel might sound dispiriting:

People really don’t want to know who they are [in a game]. This was an interesting learning process for everyone at Infocom. We weren’t really writing interactive fiction — I don’t care what you call it, I don’t care what you market it as. It’s not fiction. They’re adventure games. You want to give the player the opportunity to put themselves in an environment as if they were really there.

Here we see again that delicate balancing act between art and commerce which always marked Infocom. When they found they had gone a step too far with their literary ambitions, as with Infidel and its antihero protagonist (it sold by far the fewest copies of any of their first ten games), they generally took a step back to more traditional models.

It’s tempting to make poor Scorpia our scapegoat in this, to use her as the personification of all the hidebound traditional players who refused to pull their heads out of the Zork mentality and make the leap to approaching Infocom’s games as the new form of interactive literature they were being advertised as in the likes of The New York Times Book Review. Before we do, however, we should remember that Scorpia and people like her were paying $30 or $40 for the privilege of playing each new Infocom game. If they expected a certain sort of experience for their money, so be it; we shouldn’t begrudge people their choice in entertainment. It’s also true that Infidel could have done a better job of selling the idea. Its premise boils down to: “Greedy, charmless, incompetent asshole gets in way over his head through clumsy deceptions and generally treating the people around him like shit, and finally gets himself killed.” One might be tempted to call Infidel an interactive tragedy, but its nameless protagonist doesn’t have the slinky charm of Richard III, much less the tortured psyche of Hamlet. We’re left with just a petty little person doing petty little things, and hoisted from his own petty little petard in consequence. Such is not the stuff of great drama, even if it’s perhaps an accurate depiction of most real-life assholes and the fates that await them. If we set aside our admiration for Berlyn’s chutzpah to look at the story outside of its historical context, it doesn’t really have much to say to us about the proverbial human condition, other than “if you must be a jerk, at least be a competent jerk.” Indeed, there’s a certain nasty edge to Infidel that doesn’t seem to stem entirely from its theme. This was, we should remember, a game that Mike Berlyn didn’t really want to write, and we can feel some of his annoyance and impatience in the game itself. There’s little of the joy of creation about it. It’s just not a very lovable game. Scorpia’s distaste and unwillingness to grant Infidel the benefit of any doubt might be disappointing, but it’s understandable. One could easily see it as a sneering “up yours!” to Infocom’s loyal customers.

Infidel‘s sales followed an unusual pattern. Released in November of 1983 as Infocom’s tenth game and fifth and final of that year, it exploded out of the gate, selling more than 16,000 copies in the final weeks of the year. After that, however, sales dropped off quickly; it sold barely 20,000 copies in all of 1984. It was the only one of the first ten games to fail to sell more than 70,000 copies in its lifetime. In fact, it never even came close to 50,000. While not a commercial disaster, its relative under-performance is interesting. One wonders to what extent angry early buyers like Scorpia dissuaded others from buying it. Of course, the mercurial Berlyn’s declaring his dissatisfaction with his own game in an online conference likely didn’t help matters either. Marketing, who suffered long and hard at the hands of the Imps, must have been apoplectic after reading that transcript.

So, Infocom ended 1983 as they had begun it, with a thorny but fascinating Mike Berlyn game. With by far the most impressive catalog in adventure gaming and sales to match, they were riding high indeed. The next year would bring five more worthy games and the highest total sales of the company’s history, but also the first serious challengers to their position as the king of literate, sophisticated adventure gaming and the beginning in earnest of the Cornerstone project that sowed the seeds of their ultimate destruction. We’ll get to those stories down the road, but first we have some other ground to cover.

(I must once again thank Jason Scott for sharing with me additional materials from his Get Lamp project for this article.)