In computer parlance, a clone is Company B’s copycat version of Company A’s computer that strains to be as software and hardware compatible with its inspiration as possible. For a platform to make an attractive target for cloning, it needs to meet a few criteria. The inspiration needs to be simple and/or well-documented enough that it’s practical for another company — and generally a smaller company at that, with far fewer resources at its disposal — to create a compatible knock-off in the first place. Then the inspiration needs to be successful enough that it’s spawned an attractive ecosystem that lots of people want to be a part of. And finally, there needs to be something preventing said people from joining said ecosystem by, you know, simply buying the machine that’s about to be cloned. Perhaps Company A, believing it has a lock on the market, keeps the price above what many otherwise interested people are willing or able to pay; perhaps Company A has simply neglected to do business in a certain part of the world filled with eager would-be buyers.

Clones have been with us almost from the moment that the trinity of 1977 kicked off the PC revolution in earnest. The TRS-80 was the big early winner of the trio thanks to its relatively low price and wide distribution through thousands of Radio Shack stores, outselling the Apple II in its first months by margins of at least twenty to one (as for the Commodore PET, it was the Bigfoot of the three, occasionally glimpsed in its natural habitat of trade-show booths but never available in a form you could actually put your hands on until well into 1978). The first vibrant, non-business-focused commercial software market in history sprung up around the little Trash 80. Cobbled together on an extreme budget out of generic parts that were literally just lying around at Radio Shack — the “monitor,” for instance, was just a cheap Radio Shack television re-purposed for the role — the TRS-80 was eminently cloneable. Doing so didn’t make a whole lot of sense in North America, where Radio Shack’s volume manufacturing and distribution system would be hard advantages to overcome. But Radio Shack had virtually no presence outside of North America, where there were nevertheless plenty of enthusiasts eager to join the revolution.

A shindig for EACA distributors in Hong Kong. Shortly after this photo was taken, Eric Chung, third from right in front, would abscond with $10 million and that would be that for EACA.

The most prominent of the number of TRS-80 cloners that had sprung up by 1980 was a rather shady Hong Kong-based company called EACA, who made cheap clones for any region of the world with distributors willing to buy them. Their knock-offs popped up in Europe under the name “The Video Genie”; in Australasia as the “Dick Smith System 80,” distributed under the auspices of Dick Smith Electronics, the region’s closest equivalent to Radio Shack; even in North America as the “Personal Micro Computers PMC-80.” EACA ended in dramatic fashion in 1983 when founder Eric Chung absconded to Taiwan with all of his company’s assets that he could liquify, $10 million worth, stuffed into his briefcase. He or his descendants are presumably still living the high life there today.

By the time of those events, the TRS-80’s heyday was already well past, its position as the most active and exciting PC platform long since having been assumed by the Apple II, which had begun a surge to the fore in the wake of the II Plus model of 1979. The Apple II was if anything an even more tempting target for cloners than the TRS-80. While Steve Wozniak’s hardware design is justly still remembered as a marvel of compact elegance, it was also built entirely from readily available parts, lacking the complex and difficult-to-duplicate custom chips of competitors like Atari and Commodore. Wozniak had also insisted that every last diode on the Apple II’s circuit board be meticulously documented for the benefit of hackers just like him. And Apple, then as now, maintained some of the highest profit margins in the industry, creating a huge opportunity for a lean-and-mean cloner to undercut them.

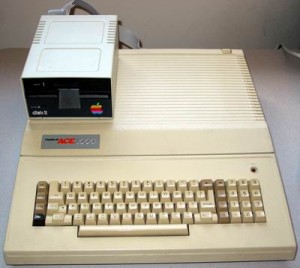

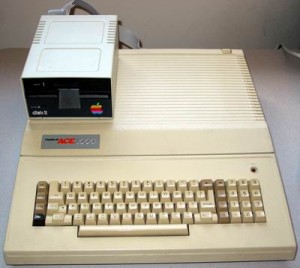

A Franklin Ace 1000 mixed and matched with a genuine Apple floppy drive.

Assorted poorly distributed Far Eastern knock-offs aside, the first really viable Apple II clone arrived in mid-1982 in the form of the Franklin Ace line. The most popular model, the Ace 1000, offered for about 25 percent less than a II Plus complete hardware and software compatibility while also having more memory as well as luxuries like a numeric keypad and upper- and lowercase letter input. The Ace terrified Apple. With the Apple III having turned into a disaster, Apple remained a one-platform company, completely dependent on continuing Apple II sales — and continuing high Apple II profit margins — to fund not one but two hugely ambitious, hugely innovative, and hugely expensive new platform initiatives, Lisa and Macintosh. A viable market in Apple II workalikes which cut seriously into sales, or that forced price cuts, could bring everything down around their ears. Already six months before the Ace actually hit the market, as soon as they got word of Franklin’s plans, Apple’s lawyers were therefore looking for a way to challenge Franklin in court and drive their machine from the market.

As it turned out, the basis for a legal challenge wasn’t hard to find. Yes, the Apple II’s unexceptional hardware would seem to be fair game — but the machine’s systems software was not. Apple quickly confirmed that, like most of the TRS-80 cloners, Franklin had simply copied the contents of the II’s ROM chips; even bugs and the secret messages Apple’s programmers had hidden inside them were still there in Franklin’s versions. A triumphant Apple rushed to federal court to seek a preliminary injunction to keep the Ace off the market until the matter was decided through a trial. Much to their shocked dismay, the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania found the defense offered by Franklin’s legal team compelling enough to deny the injunction. The Ace came out right on schedule that summer of 1982, to good reviews and excellent sales.

Franklin’s defense sounds almost unbelievable today. They readily admitted that they had simply copied the contents of the ROM chips. They insisted, however, that the binary code contained on the chips, being a machine-generated sequence of 1s and 0s that existed only inside the chips and that couldn’t be reasonably read by a human, was not a form of creative expression and thus not eligible for copyright protection in the first place. In Franklin’s formulation, only the human-readable source code used to create the binary code stored on the ROM chips, which Franklin had no access to and no need for given that they had the binary code, was copyrightable. It was an audacious defense to say the least, one which if accepted would tear down the legal basis for the entire software industry. After all, how long would it take someone to leap to the conclusion that some hot new game, stored only in non-human-readable form on a floppy disk, was also ineligible for copyright protection? Astonishingly, when the case got back to the District Court for a proper trial the judge again sided with Franklin, stating that “there is some doubt as to the copyrightability of the programs described in this litigation,” in spite of an earlier case, Williams Electronics, Inc. v. Arctic International, Inc., which quite clearly had established binary code as copyrightable. Only in August of 1983 was the lower court’s ruling overturned by the Federal Court of Appeals in Philadelphia. A truculent Franklin threatened to appeal to the Supreme Court, but finally agreed to a settlement that January that demanded they start using their own ROMs if they wanted to keep cloning Apple IIs.

Apple Computer, Inc., v. Franklin Computer Corp. still stands today as a landmark in technology jurisprudence. It firmly and finally established the copyrightable status of software regardless of its form of distribution. And it of course also had an immediate impact on would-be cloners, making their lives much more difficult than before. With everyone now perfectly clear on what was and wasn’t legal, attorney David Grais clarified the process cloners would need to follow to avoid lawsuits in an episode of Computer Chronicles:

You have to have one person prepare a specification of what the program [the systems software] is supposed to do, and have another person who’s never seen the [original] program write a program to do it. If you can persuade a judge that the second fellow didn’t copy from the [original] code, then I think you’ll be pretty safe.

After going through this process, Apple II cloners needed to end up with systems software that behaved absolutely identically to the original. Every system call needed to take the exact same amount of time that it did on a real Apple II; each of the original software’s various little quirks and bugs needed to be meticulously duplicated. Anything less would bring with it incompatibility, because there was absolutely nothing in those ROMs that some enterprising hacker hadn’t used in some crazy, undocumented, unexpected way. This was a tall hurdle indeed, one which neither Franklin nor any other Apple II cloner was ever able to completely clear. New Franklins duly debuted with the new, legal ROMs, and duly proved to be much less compatible and thus much less desirable than the older models. Franklin left the Apple-cloning business within a few years in favor of hand-held dictionaries and thesauri.

There is, however, still another platform to consider, one on which the cloners would be markedly more successful: the IBM PC. The open or (better said) modular architecture of the IBM PC was not, as so many popular histories have claimed, a sign of a panicked or slapdash design process. It was rather simply the way that IBM did business. Back in the 1960s the company had revolutionized the world of mainframe computing with the IBM System/360, not a single computer model but a whole extended family of hardware and software designed to plug and play together in whatever combination best suited a customer’s needs. It was this product line, the most successful in IBM’s history, that propelled them to the position of absolute dominance of big corporate computing that they still enjoyed in the 1980s, and that reduced formerly proud competitors to playing within the house IBM had built by becoming humble “Plug-Compatible Manufacturers” selling peripherals that IBM hadn’t deigned to provide — or, just as frequently, selling clones of IBM’s products for lower prices. Still, the combined profits of all the cloners remained always far less than those of IBM itself; it seemed that lots of businesses wanted the security that IBM’s stellar reputation guaranteed, and were willing to pay a bit extra for it. IBM may have thought the PC market would play out the same way. If so, they were in for a rude surprise.

The IBM PC was also envisioned as not so much a computer as the cornerstone of an ever-evolving, interoperable computing family that could live for years or decades. Within three years of the original machine’s launch, you could already choose from two CPUs, the original Intel 8088 or the new 80286; could install as little as 16 K of memory or as much as 640 K; could choose among four different display cards, from the text-only Monochrome Display Adapter to the complicated and expensive CAD-oriented Professional Graphics Controller; could choose from a huge variety of other peripherals: floppy and hard disks, tape backup units, modems, printer interfaces, etc. The unifying common denominator amongst all this was a common operating system, MS-DOS, which had quickly established itself as the only one of the four operating paradigms supported by the original IBM PC that anyone actually used. Here we do see a key difference between the System/360 and the IBM PC, one destined to cause IBM much chagrin: whereas the former ran an in-house-developed IBM operating system, the operating system of the latter belonged to Microsoft.

The IBM architecture was different from that of the Apple II in that its operating system resided on disk, to be booted into memory at system startup, rather than being housed in ROM. Still, every computer needs to have some code in ROM. On an IBM PC, this code was known as the “Basic Input/Output System,” or BIOS, a nomenclature borrowed from the CP/M-based machines that preceded it. The BIOS was responsible on startup for doing some self-checks and configuration and booting the operating system from disk. It also contained a set of very basic, very low-level routines to do things like read from and write to the disks, detect keyboard input, or display text on the screen; these would be called constantly by MS-DOS and, very commonly, by applications as well while the machine was in operation. The BIOS was the one piece of software for the IBM PC that IBM themselves had written and owned, and for obvious reasons they weren’t inclined to share it with anyone else. Two small companies, Corona Labs and Eagle Computer, would simply copy IBM’s BIOS à la Franklin. It took the larger company all of one day to file suit and force complete capitulation and market withdrawal when those machines came to their attention in early 1984.

Long before those events, other wiser would-be cloners recognized that creating a workalike, “clean-room” version of IBM’s BIOS would be the key to executing a legal IBM clone. The IBM PC’s emphasis on modularity and future expansion meant that it was a bit more forgiving in this area than the likes of the more tightly integrated Apple II. Yet an IBM-compatible BIOS would still be a tricky business, fraught with technical and financial risk.

As the IBM PC was beginning to ship, a trio of Texas Instruments executives named Rod Canion, James Harris, and William Murto were kicking around ideas for getting out from under what they saw as a growing culture of non-innovation inside TI. Eager to start a business of their own, they considered everything from a Mexican restaurant to household gadgets like a beeper for finding lost keys. Eventually they started to ask what the people around them at TI wanted but weren’t getting in their professional lives. They soon had their answer: a usable portable computer that executives and engineers could cart around with them on the road, and that was cheap enough that their purchasing managers wouldn’t balk. Other companies had explored this realm before, most notably the brief-lived Osborne Computer with the Osborne 1, but those products had fallen down badly in the usability sweepstakes; the Osborne 1, for example, had a 5-inch display screen the mere thought of which could prompt severe eye strain in those with any experience with the machine, disk drives that could store all of 91 K, and just 64 K of memory. Importantly, all of those older portables ran CP/M, until now the standard for business computing. Canion, Harris, and Murto guessed, correctly, that CP/M’s days were numbered in the wake of IBM’s adoption of MS-DOS. Not wanting to be tied to a dying operating system, they first considered making their own. Yet when they polled the big software publishers about their interest in developing for yet another new, incompatible machine the results were not encouraging. There was only one thing for it: they must find a way to make their portable compatible with the IBM PC. If they could bring out such a machine before IBM did, the spoils could be enormous. Prominent tech venture capitalist Ben Rosen agreed, investing $2.5 million to help found Compaq Computer Corporation in February of 1982. What with solid funding and their own connections within the industry, Canion, Harris, and Murto thought they could easily design a hardware-compatible portable that was better than anything else available at the time. That just left the software side.

Given Bill Gates’s reputation as the Machiavelli of the computer industry, we perhaps shouldn’t be surprised that some journalists have credited him with anticipating the rise of PC clones from well before the release of the first IBM PC. That, however, is not the case. All indications are that Gates negotiated a deal that let Microsoft lease MS-DOS to IBM rather than sell it to them simply in the expectation that the IBM PC would be a big success, enough so that an ongoing licensing fee would amount to far more than a lump-sum payout in the long run. Thus he was as surprised as anyone when Compaq and a few other early would-be cloners contacted him to negotiate MS-DOS license deals for their own machines. Of course, Gates being Gates, it took him all of about ten minutes to grasp the implications of what was being requested, and to start making deals that, not incidentally, actually paid considerably better than the one he’d already made with IBM.

The BIOS would be a tougher nut to crack, the beachhead on which this invasion of Big Blue’s turf would succeed or fail. Having quickly concluded that simply copying IBM’s ROMs wasn’t a wise option, Compaq hired a staff of fifteen programmers who would dedicate the months to come to creating a slavish imitation. Programmers with any familiarity at all with the IBM BIOS were known as “dirty,” and barred from working on the project. Instead of relying on IBM’s published BIOS specifications (which might very well be incorrect due to oversight or skulduggery), the team took the thirty biggest applications on the market and worked through them one at a time, analyzing each BIOS call each program made and figuring out through trial and error what response it needed to receive. The two trickiest programs, which would go on to become a sort of stress test for clone compatibility both inside and outside of Compaq, proved to be Lotus 1-2-3 and Microsoft Flight Simulator.

Before the end of the year, Compaq was previewing their new portable to press and public and working hard to set up a strong dealer network. For the latter task they indulged in a bit of headhunting: they hired away from IBM H. L. ”Sparky” Sparks, the man who had set up the IBM PC dealer network. Knowing all too well how dealers thought and what was most important to them, Sparks instituted a standard expected dealer markup of 36 percent, versus the 33 percent offered by IBM, thus giving them every reason to look hard at whether a Compaq might meet a customer’s needs just as well or better than a machine from Big Blue.

Compaq’s first computer, the Portable

Savvy business realpolitik like that became a hallmark of Compaq. Previously clones had been the purview of small upstarts, often with a distinct air of the fly-by-night about them. The suburban-Houston-based Compaq, though, was different, not only from other cloners but also from the established companies of Silicon Valley. Compaq was older, more conservative, interested in changing the world only to the extent that that meant more Compaq computers on desks and in airplane luggage racks. ”I don’t think you could get a 20-year-old to not try to satisfy his ego by ‘improving’ on IBM,” said J. Steven Flannigan, the man who led the BIOS reverse-engineering effort. “When you’re fat, balding, and 40, and have a lot of patents already, you don’t have to try.” That attitude was something corporate purchasing managers could understand. Indeed, Compaq bore with it quite a lot of the same sense of comforting stolidity as did IBM itself. Not quite the first to hit the market with an IBM clone with a “clean” BIOS (that honor likely belongs to Columbia Data Products, a much scruffier sort of operation that would be out of business by 1985), Compaq nevertheless legitimized the notion in the eyes of corporate America.

The worst possible 1980s airplane seatmate: a business traveler lugging along a Compaq Portable.

Yet the Compaq Portable that started shipping very early in 1983 also succeeded because it was an excellent and — Flannigan’s sentiments aside — innovative product. By coming out with their portable before IBM itself, Compaq showed that clones need not be mere slavish imitations of their inspirations distinguished only by a lower price. “Portable” in 1983 did not, mind you, mean what it does today. The Compaq Portable was bigger and heavier — a full 28 pounds — than most desktop machines of today, something you manhandled around like a suitcase rather than slipping into a pocket or backpack. There wasn’t even a battery in the thing, meaning the businessperson on the go would likely be doing her “portable” computing only in her hotel room. Still, it was very thoughtfully designed within the technical constraints of its era; you could for instance attach it to a real monitor at your desk to enjoy color graphics in lieu of the little 9-inch monochrome screen that came built-in, a first step on the road to the ubiquitous laptop docking stations of today.

Launching fortuitously just as some manufacturing snafus and unexpected demand for the new PC/XT were making IBM’s own computers hard to secure in some places, the Compaq Portable took off like a rocket. Compaq sold 53,000 of them for $111 million in sales that first year, a record for a technology startup. IBM, suddenly in the unaccustomed position of playing catch-up, released their own portable the following year with fewer features but — and this was truly shocking — a lower price than the Compaq Portable; by forcing high-and-mighty IBM to compete on price, Compaq seemed to have somehow turned the world on its head. The IBM Portable PC was a notable commercial failure, first sign of IBM’s loosening grip on the monster they had birthed. Meanwhile Compaq launched their own head-to-head challenge that same year with the DeskPro line of desktop machines, to much greater success. Apple may have been attacking IBM in melodramatic propaganda films and declaring themselves and IBM to be locked in a battle of Good versus Evil, but IBM hardly seemed to notice the would-be Apple freedom fighters. The only company that really mattered to IBM, the only company that scared them, wasn’t sexy Apple but buttoned-down, square-jawed Compaq.

But Compaq was actually far from IBM’s only problem. Cloning just kept getting easier, for everyone. In the spring of 1984 two little companies called Award Software and Phoenix Technologies announced identical products almost simultaneously: a reverse-engineered, completely legal IBM-compatible BIOS which they would license to anyone who felt like using it to make a clone. Plenty of companies did, catapulting Award and Phoenix to the top of what was soon a booming niche industry (they would eventually resolve their rivalry the way that civilized businesspeople do it, by merging). With the one significant difficulty of cloning thus removed, making a new clone became almost a triviality, a matter of ordering up a handful of components along with MS-DOS and an off-the-shelf BIOS, slapping it all together, and shoving it out the door; the ambitious hobbyist could even do it in her home if she liked. By 1986, considerably more clones were being sold than IBMs, whose own sales were stagnant or even decreasing.

That year Intel started producing the 80386, the third generation of the line of CPUs that powered the IBM PC and its clones. IBM elected to wait a bit before making use of it, judging that the second-generation 80286, which they had incorporated into the very successful PC/AT in 1984, was still plenty powerful for the time being. It was a bad decision, predicated on a degree of dominance which IBM no longer enjoyed. Smelling opportunity, Compaq made their own 80386-based machine, the DeskPro 386, the first to sport the hot new chip. Prior to this machine, the cloners had always been content to let IBM pave the way of such fundamental advances. The DeskPro 386 marks Compaq’s — and the clone industry’s — coming of age. No longer just floating along in the wake of IBM, tinkering with form factors, prices, and feature sets, now they were driving events. Already in November of 1985, Bill Machrone of PC Magazine had seen where this was leading: “Now that it [IBM] has created the market, the market doesn’t necessarily need IBM for the machines.” We see here business computing going through its second fundamental shift (the first being the transition from CP/M to MS-DOS). What was an ecosystem of IBM and IBM clones now became a set of sometimes less-than-ideal, sometimes accidental, but nevertheless agreed-upon standards that were bigger than IBM or anyone else. IBM, Machrone wrote, “had better conform” to the standards or face the consequences just like anyone else. Tellingly, it’s at about this time that we see the phrase “IBM clone” begin to fade, to be replaced by “MS-DOS machine” or “Intel-based machine.”

The emerging Microsoft/Intel juggernaut (note the lack of an “IBM” in there) would eventually conquer the home as well. Already by the mid-1980s certain specimens of the breed were beginning to manifest features that could make them attractive for the home user. Let’s rewind just slightly to look at the most important of them, which I’ve mentioned in a couple of earlier articles but have never really given its full due.

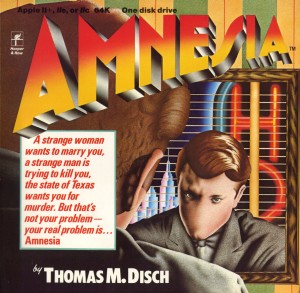

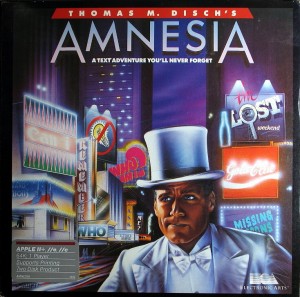

When the folks at Radio Shack, trying to figure out what to do with their aging, fading TRS-80 line, saw the ill-fated IBM PCjr, they saw things well worth salvaging in its 16-color graphics chip and its three-voice sound synthesizer, both far superior to the versions found in its big brothers. Why not clone those pieces, package them into an otherwise fairly conventional PC clone, and sell the end result as the perfect all-around computer, one which could run all the critical business applications but could also play games in the style to which kids with Commodore 64s were accustomed? Thanks to the hype that had accompanied the PCjr’s launch, there were plenty of publishers out there with huge inventories of games and other software that supported the PCjr’s audiovisuals, inventories they’d be only too eager to unload on Radio Shack cheap. With those titles to prime the pump, who knew where things might go…

Launched in late 1984, the Tandy 1000 was the first IBM clone to be clearly pitched not so much at business as at the ordinary consumer. In addition to the audiovisual enhancements and very aggressive pricing, it included DeskMate, a sort of proto-GUI operating environment designed to insulate the user from the cryptic MS-DOS command prompt while giving access to six typical home applications that came built right in. A brilliant little idea all the way around, the Tandy 1000 rescued Radio Shack from the brink of computing irrelevance. It also proved a godsend for many software publishers who’d bet big on the PCjr; John Williams credits it with literally saving Sierra by providing a market for King’s Quest, a game Sierra had developed for the PCjr at horrendous expense and to underwhelming sales given that platform’s commercial failure. Indeed, the Tandy 1000 became so popular that it prompted lots of game publishers to have a second look at the heretofore dull beige world of the clones. As they jumped aboard the MS-DOS gravy train, many made sure to take advantage of the Tandy 1000’s audiovisual enhancements. Thousands of titles would eventually blurb what became known as “Tandy graphics support” on their boxes and advertisements. Having secured the business market, the Intel/Microsoft architecture’s longer, more twisting road to hegemony over home computing began in earnest with the Tandy 1000. And meanwhile poor IBM couldn’t even get proper credit for the graphics standard they’d actually invented. Sometimes you just can’t win for losing.

Another sign of the nascent but inexorably growing power of Intel/Microsoft in the home would come soon after the Tandy 1000, with the arrival of the first game to make many Apple, Atari, and Commodore owners wish that they had a Tandy 1000 or, indeed, even one of its less colorful relatives. We’ll get to that soon — no, really! — but first we have just one more detour to take.

(I was spoiled for choice on sources this time. A quick rundown of periodicals: Creative Computing of January 1983; Byte of January 1983, November 1984, and August 1985; PC Magazine of January 1987; New York Times of November 5 1982, October 26 1983, January 5 1984, February 1 1984, and February 22 1984; Fortune of February 18 1985. Computer Wars by Charles H. Ferguson and Charles R. Morris is a pretty complete book-length study of IBM’s trials and tribulations during this period. More information on the EACA clones can be found at Terry Stewart’s site. More on Compaq’s roots in Houston can be found at the Texas Historical Association. A few more invaluable links are included in the article proper.)