The Outcast box was styled to look like a movie poster. Riffing on the same theme, Infogrames’s head Bruno Bonnell called it “the first videogame that really tries to be an interactive movie,” leaving one to wonder whether he had somehow missed the first nine years of the 1990s, during which countless games tried desperately to be just that. Ironically, Outcast actually has very few of the characteristics that had become associated with the phrase: no rigidly linear plot, no digitized human actors, no out-of-engine cutscenes after the obligatory opening one. It’s a game rather than a movie through and through, and all the better for it.

As longtime readers of these histories know already, I’ve never been overly enamored with the so-called “French Touch” in vintage computer games, that blending of elevated aesthetic and thematic aspirations — some might prefer to use the word “pretensions” — with a, shall we say, less thoroughgoing commitment to the details of gameplay and mechanics. So, I approached Outcast, a 1999 game by the Francophone Belgian studio Appeal, with my prejudices held out in front of me like a shield. The descriptions I read of Outcast were full of things that set my spider sense tingling: a blending of wildly divergent, usually mutually exclusive gameplay genres (it’s hard enough to get one type of game right, much less multiple types); a relentlessly diegetic interface that embraces even such typically meta-activities as saving state (it’s hard enough to get an interface right without also trying to extend it into the world of the game); a fiendishly and seemingly needlessly convoluted premise (whereas bad Anglophone games make Donald Duck seem like Shakespeare, bad French ones all seem to be trying to be Victor Hugo and Marcel Proust rolled into one). In fact, I did my level best to avoid writing about Outcast at all, even though I knew it to be one of the better remembered cult classics of the millennial era. But when my reader Deckard asked me to cover it with “big pleading puss-in-boots eyes,” I felt like I owed it to him and all of you to at least give it a look.

Well, then, there’s no point in burying the lede any deeper than I already have: I did play Outcast. Much to my own surprise, I wound up playing it all the way through, and kind of loving it. By no means was I left without nitpicks and niggles, but on the whole it proved to be not just one of the more interesting games I’ve encountered recently but one of the more fun as well. It succeeds on most of the divergent vectors it dares to venture down, delivering a unique, evocative, even moving experience that I won’t soon forget. I owe Deckard a hearty thank you for giving me the push I needed. Read on to find out all the reasons I have to be grateful, plus a little something about where Outcast came from.

At bottom, Outcast was a labor of love by three fast friends who had been working and playing together for years by the time they started to make it. One of the trio, named Franck Sauer, was a visual artist, sound designer, and rudimentary musician, while the other two, named Yves Grolet and Yann Robert, were accomplished programmers who specialized in high-performance graphics. When they were first coming up in the industry, the Commodore Amiga was still Europe’s premier gaming platform. They first made a reputation for themselves via two audiovisually innovative, mechanically rote shoot-em-ups of the sort that were a dime a dozen on the Amiga at the time: 1990’s Unreal (no, not that one) and 1992’s Agony. Each sold around 20,000 copies in a crowded market.

Worried about the Amiga’s long-term future as a platform — and justifiably so, as it would turn out — the friends then decided to look elsewhere. They applied and were approved for a business-development grant from the government of France — this was made possible by the fact that Yann Robert was a citizen of that country rather than Belgium — and embarked on an ambitious plan to make standup-arcade games, a branch of the industry that was enjoying its last flash of rude health before the unceasing evolution of digital technology for the home rendered it moot. Art & Magic, as they called their company, succeeded in shipping four such games during 1993 and 1994; the actual hardware was manufactured by a Belgian firm known as Deltatec. The first of their games, Ultimate Tennis, performed the best, with some 5000 cabinets sold. Those that followed did steadily less well, and soon the friends decided to jump ship from the softening arcade market just as they had from the Amiga.

Determined to continue making games despite the lukewarm financial rewards their efforts thus far had yielded, they started another company, which they called Appeal, and considered where to go next. With DOOM having recently swept the world, 3D graphics were all the rage in gaming circles. Unconvinced that they could compete head-on with John Carmack and the other talented programmers at id Software, who were already hard at work on Quake, Grolet and Robert opted to try something different on the same Intel-based personal computers that id was targeting. Instead of embracing polygonal 3D rendering, as id and everyone else were doing, they thought to make an engine powered by voxels: essentially, individual pixels that each came complete with an X, Y, and Z coordinate to place it in a 3D space independently, untethered to any polygons. The approach had its limitations — it was less efficient than polygonal graphics in many applications, and far less amenable to hardware acceleration — but it had some notable advantages as well. In particular, it ought to be good at rendering large, open, sun-drenched landscapes, something that the polygonal engines all struggled with. Whereas they favored symmetrical straight lines that were best suited for buildings and other human-made scenery, voxels could do a credible job of rendering the more chaotic, convex splendors of nature.

The friends made a trip to France to pitch the game they called Outcast to the two biggest publishers in Francophone gaming, the Paris-based Ubisoft and the Lyon-based Infogrames. The former turned them down flat; the latter agreed to buy a minority stake in Appeal and to fund the project after just a few days of talks. Grolet, Robert, and Sauer set up shop in the Belgian town of Namur and embarked upon what would turn into a four-year odyssey, alongside a development team that would grow to about twenty people at its peak.

In the beginning, Outcast was a project driven almost exclusively by its graphics technology, just like everything else the friends had done prior to it. To whatever extent they thought about the gameplay and the fiction, it was as a way to showcase the potential of voxel graphics to best effect. That meant large outdoor spaces to set it apart from the DOOMs and Quakes of the world. The first draft of the plot took place in the jungles of South America, casting the player as a vigilante who goes to war with a gang of drug smugglers. But the friends soon concluded that an alien environment would be better, in that it would show off the visuals without drawing attention to the many ways they could fail to deliver an accurate rendering of the flora and fauna of our own planet; voxels were better at impressionism than photo-realism. Then someone had the idea that, if one outdoor environment would be good, a collection of them to hop among, each with its own aesthetic personality, would be even better. For a good two years, the fiction and the gameplay failed to advance much farther than that, while Appeal worked on their tech and built out the environments in which the game would take place.

There was a danger in letting any such technology-first project drag on for so long, in that consumer-computing hardware in the second half of the 1990s was very much a moving target. When work on Outcast began, most games were still running under MS-DOS, using unaccelerated VGA graphics running at a typical resolution of 320 X 200. The next few years would see Windows 95 and its DirectX libraries finally replace the MS-DOS command line that had been so familiar to gamers for so long, even as SVGA graphics running at a resolution of 640 X 480 or higher became the norm and 3D graphics accelerators became commonplace. Appeal had to reckon with and adjust to these sweeping changes as best they could. They made the switch to Windows, but their voxels were not able to make use of 3D-acceleration cards. In order to keep frame rates reasonable, they had to settle for the rather odd resolution of 512 X 384, a middle ground between the past and present of computer-game graphics.

Outcast’s graphics weren’t terribly impressive in the numeric terms by which such things were usually judged: resolution, texture density, etc. Yet they have an impressionistic beauty all their own. After living with the dark, rather sterile graphics that dominated at the time, booting up Outcast was like opening the curtains in a dark room to let in the light of a gorgeous summer day.

From about the halfway point in its development, Outcast began to expand its horizons, to become something much more than just another graphical showcase. This was accompanied by the arrival of some new characters from outside the somewhat insular world of French gaming. They would come to have an enormous impact on the finished product.

Alongside their French artiness, the core trio were possessed of a huge fondness for big-budget American action movies and their typically bombastic scores. Franck Sauer especially wanted Outcast to have a bold, striking soundtrack to accompany its unique visuals; he cited John Williams, Alan Silvestri, and Danny Elfman as appropriate points of departure. Knowing that such a feat of composition was well beyond his own modest musical talents, he placed an advertisement in some American film-industry magazines, and eventually settled on a Hollywood-based composer named Lennie Moore. Moore was given permission just to go for it. The music he came up with was sometimes wildly, almost comically over the top — he names the pull-out-all-the-stops operas of Richard Wagner as one of his most important influences — but it was like nothing else that had been heard in a game before.

Best of all, Moore happened to have a relationship with the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. The peculiar economics of post-Soviet Russia, where institutions like the aforementioned orchestra had been cast adrift without the state patronage under which they had thrived in previous decades, meant that they were often willing to take on “low-culture” music like videogame scores that no similarly credentialed Western cultural standard bearer would have touched, for a price it would never have countenanced. So, Lennie Moore and Franck Sauer found themselves traveling to Moscow in the summer of 1997, to spend a week recording the soundtrack with an 81-piece orchestra and a 24-member vocal choir, conducted by another American named William Stromberg. Sitting in an empty auditorium listening to the music being performed for the benefit of the tape recorders, Sauer could hardly believe his ears; he still calls it “an experience of a lifetime.”

Outcast was suddenly taking on a decidedly multinational personality. Indeed, Moore’s score made use of a variety of exotic instrumentation in addition to the orchestra and choir, such as an Armenian duduk, Indian tablas, and African congas. The choir sang passages from Virgil’s Aeneid in the original Latin.

Around the same time that Lennie Moore and William Stromberg came onboard, Appeal hired yet another American, a writer and game designer by the name of Douglas Freese who would spend the next two years with them in Belgium. His assignment was to come up with an overarching plot to join together the six disparate voxel-driven environments that had already been created, and then to write all of the dialog for the many characters the player would encounter there. For it had been decided that Outcast would be, despite its Francophone origins, an English-language production first and foremost, one that could then be localized back into French and other languages as necessary. Writing from my own selfish standpoint as a native English speaker who prefers to play games in that language, this strikes me as a pivotal decision. It means that the Outcast which I know isn’t afflicted with the layer of obfuscation that tends to make playing even well-translated games — to say nothing of the bad translations! — like peering at their worlds through a window coated with a thin rime of frost.

Is the story of Outcast a good story? That depends on how you look at it. In the broadest strokes, it’s both clichéd and convoluted. You play a former Navy SEAL by the name of Cutter Slade — has there ever been a more perfect action-hero name in the history of media? — who is part of the first team of Earthlings ever to use a newly invented piece of mad-scientist kit that enables one to visit a parallel universe. (The influence of Stargate SG-1, a very popular television show at the time, is strong with this one.) But this is no casual research trip for the team: a black hole has been created in our own dimension by an unmanned probe that was sent previously into the alternate one. The rift can be closed only by locating the probe and returning it to the dimension where it belongs.

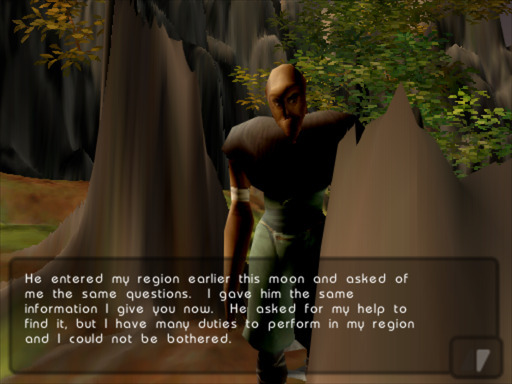

Your alter ego Cutter Slade. While the backgrounds are rendered using voxels, foreground characters and objects are rendered using more traditional polygons. Even here, however, Appeal found a way to be innovative. The game was one of the first, if not the first, to use a texture-mapping technique called bump-mapping to render action-hero musculature.

Alas, something goes haywire on your trip between dimensions as well, and the four members of your team arrive on the world of Adelpha at widely scattered points in not just geography but also time, with their equipment — including Cutter Slade’s action-hero arsenal of advanced weaponry — likewise scattered hither and yon. And so the game proper begins. In the role of Cutter, all you really want to do is locate your three companions, locate the probe, and return along with them and it to your home dimension, but it turns out that in order to do that you have to defeat a dictator who has taken over Adelpha and is suppressing its alien inhabitants with standard dictatorial glee. This is the task to which you’ll find yourself devoting the vast majority of your time and energy.

As I already noted, this story is as contrived as any in the videogame space, not to mention riddled with plot holes bigger than the inter-dimensional rift itself. (If the probe is such a problem for the stability of the multiverse, why doesn’t the other Earth equipment that’s been scattered everywhere on Adelpha seem to be any cause for concern?) The saving grace is in the details. Cutter Slade at first seems like just another one of the musclebound onscreen ciphers in which Arnold Schwarzenegger once specialized, but, once you get to know him, he turns out to conform more to the Bruce Willis or Harrison Ford archetype. (The voice actor who plays Cutter in the French localization is actually the same one who dubbed over Willis’s voice in the French Die Hard.) He’s always quick with a quip, expressing appropriate exasperation every time he’s given Yet Another Fetch Quest to carry out by one of the huge number of characters who inhabit the six regions of Adelpha, but he’s a soft touch at heart. He proves to be good company for his player, thus fulfilling the first and most important requirement for any videogame avatar. He’s so likable that you really want to bring his story to a happy ending.

Cutter Slade is a fish out of water much but not all of the time on Adelpha: being a former Navy SEAL, he’s pretty good at swimming as well as running, crawling, hitting, and shooting. “As far as Cutter is concerned, I had an easy time with his dialog because we both were in alien lands — him Adelpha, me Belgium — and we both had something to accomplish,” says Douglas Freese.

You can move from one of the six wildly disparate regions of Adelpha to another one only via the teleportation portals you find scattered about. The first region is a small training area, but the others are sprawling open spaces that show off the capabilities of the voxel engine to maximum advantage. Your main goal in each is to find a MacGuffin called a “mon,” of which you need all five in order to liberate the planet. But getting each mon will require working your way through a whole matrix of puzzles and other, preliminary quests given to you by the local inhabitants, members of a humanoid species known as the Talan. Most of the quests are self-contained within each region, but every once in a while the game switches it up and demands that you do something in another region to meet a local challenge. The whole design is impressively nonlinear; you can go almost everywhere right from the start, can tackle the regions in any order you wish. A short time after you find a mon, the game fires off a larger plot event involving your search for your missing teammates and sends you scurrying off to put out a fire somewhere and learn some more about What Is Really Going On on Adelpha. In this way, Outcast manages to balance a high degree of player freedom with a more conventional plot, with a coherent beginning, middle, and end.

The Talan are the most shiftless bunch of aliens ever. Some of them explain that they’re pacifists who cannot possibly shed blood themselves, yet they’re perfectly okay with you doing the blood-shedding for them. (Certain parallels from the real world of 2025 inevitably leap to mind, but it’s probably best if I don’t point them out here.)

Solving the many and diverse problems afflicting Cutter and his new Talan friends often entails combat; this is where the other, less cerebral side of the game’s identity comes to the fore. You can fight either from a third-person, behind-the-back perspective, Tomb Raider style, or from a first-person perspective, Quake style. Either way, you have half a dozen different weapons to experiment with — assuming you can find them and keep them fed with ammunition — and always have your sturdy action-hero fists available as a fallback option.

I found the combat in Outcast to be a blast — literally so, in the case of one of my favorite weapons, a handheld grenade launcher that makes as enjoyable an explosion as I’ve ever encountered in a game. By no means is it entirely free of jank — I had a persistent issue with getting hung up behind the bodies of my fallen enemies, whom Cutter’s SEAL training has apparently not taught him to step over — yet it seldom failed to put a smile on my face. One of the most satisfying tactics is to forgo weapons and just run up and beat the snot out of the evil Talan soldiers, Three Stooges style — one hand holding your victim by the collar, the other whaling away on his face. (For extra fun, use the one you’re beating up as a meat shield against the ones who are shooting at you.) I have to give special props to the artificial intelligence of your opponents, who do a remarkably effective job of coordinating with one another in a firefight, who are even capable of luring you into deadly ambushes if you aren’t careful.

As most of you know, this style of gameplay isn’t usually in my wheelhouse. Yet I had more genuine fun with Outcast than with any action game I’ve played for these histories since Jedi Knight. Just as is the case with that game, Outcast is full of big explosions and flying bodies, but it never gets morbid about it: there’s no blood to be seen, and corpses simply disappear after a few minutes in a puff of energy. (There’s probably some in-story explanation for that, but who can be bothered to look it up?) Meanwhile the difficulty is pitched perfectly for me, occasionally challenging but never crazily punishing, rewarding smart tactics as much or more than fast reflexes.

While it’s very easy for a review like this one to slip into talking about Outcast as a game of two halves, it doesn’t really feel that way in practice. One of its most amazing achievements is how seamless it is to play; one never gets the feeling of shifting from “adventure mode” to “shooter mode,” as one tends to do in so many cross-genre exercises. Everything takes place within the same interface, and everything you do is connected to everything else. There are plenty of dialog puzzles and object-oriented puzzles of the sort you might find in an adventure game, but there are also some physics-based puzzles that wouldn’t have been possible in a point-and-click engine: shoot a pendulum at just the right point in its sway to make it move faster and faster, drop a bomb perfectly into the bottom of a well. Solving a fetch quest might require you to fight or sneak your way past some soldiers to get what you need; then, in turn, the outcome of the quest might be to weaken the enemies you fight later by taking away some of their food supply or reducing the power of their weapons. Most of your enemies do not respawn. This means that, if you invest a lot of time and effort into cleaning up a region, it generally stays that way. Adelpha is a truly reactive world that allows for considerable variance in play styles. You can flat-out go to war on behalf of its oppressed peoples, or you can sneak around, resorting to violence only when absolutely necessary. It’s entirely up to you.

The commitment to verisimilitude in all things led the designers to attempt to provide diegetic explanations for even Outcast’s gamiest aspects. The fact that the Talan you meet are all males — presumably a byproduct of a limited voice-acting budget in the real world — is here the result of a segregated alien society, in which women and children live in a separate enclave except during mating season, when everyone comes together to get their grooves on. The fact that the Talan all know how to speak English is explained as… ah, that would be spoiling things. Moving back onto safer territory, it’s studiously related in the manual that Cutter Slade carries a “miniaturization backpack” around with him, thus explaining why it is that he can hold an infinite quantity of stuff in his inventory. The onscreen HUD as well is explained as merely the view through the “direct bio-neural interface” which Cutter wears at all times.

Of course, this sort of thing can quickly get silly: if the above hasn’t convinced you of that already, the in-game “Gaamsaav” (groan!) crystal that lets Cutter capture a snapshot in time surely will. On the other hand, even it is cleverer in design terms than it first appears. Cutter has to stand still for several seconds in order to use it, which makes it inadvisable to pull out in the middle of a firefight. In this way, Outcast deftly heads off the overuse of a save function which can rob all of the tension out of a game, without annoying and inconveniencing the player too unduly through more draconian remedies like fixed save points.

As this example illustrates, Outcast provides more than just an unusually reactive and thoughtfully realized world: it also succeeds really well as an exercise in playable game design. This is not to say that fomenting a revolution on Adelpha is easy; there is little hand-holding in this wide-open world beyond a useful if sometimes cryptic quest log. Yet the game is never unfair either. If you explore diligently and follow up on all of the information you’re given, it’s perfectly soluble. I got through it without a single hint, although it did take me a few weeks of evenings and weekend afternoons to do so. The mere fact that I was motivated enough to put in the time says a lot. I had the feeling throughout that this was a game that had been played by lots of people before it was released, that it earnestly wanted to be played and enjoyed by me now, that it was a game whose designers had thought deeply about the player’s experience. What might first seem like an aggressively uncompromising game proves to be full of thoughtful little affordances for the player who deigns to pay careful attention to what’s going on, such as the portable transporter devices that you can use to jump around to arbitrary points within a region and the handy lexicon of unfamiliar alien phrases that is automatically compiled for you as you talk to more and more Talan. It isn’t even necessary to finish all of the quests in order to finish Outcast; much of the content is optional.

I’ve expended a fair number of words on Outcast by now, but I’m not sure I’ve succeeded in capturing the sui generis quality that makes it so memorable. Needless to say, no game arises in a vacuum, and we can definitely find precedents for and possible influences upon this one if we look for them. Most obviously, it can be slotted into the long and proud European tradition of open-world action-adventures, dating back to 1980s classics like Mercenary and Exile. Then, too, it’s not hard to detect a whiff of Tomb Raider’s influence in its behind-the-back perspective and its occasional jumping puzzles. Outcast’s unflagging commitment to verisimilitude and diegesis brings to mind Looking Glass’s brilliant System Shock. The fetch quests might have come out of an Ultima game, some of the puzzles out of Myst. Yet Outcast blends it all in such a seamless way that it ends up entirely its own thing. It is, if you’ll forgive the cliché, more than the sum of its incredibly disparate parts. It shouldn’t work, but it does. It’s interactive narrative at its purest, in which the gameplay exists to serve the story and the world rather than the other way around.

“Outcast is a game made with passion, with no constraints of being tied to a particular genre or to please a particular group of people,” says Franck Sauer. “We just did the game we wanted to make, and that was it.” The end result is as groundbreaking and inspiring an attempt to make an action game where the action feels like it matters as is Half-Life. Indeed, if we’re being honest, I had a heck of a lot more fun with Outcast than I ever did with Half-Life. Personally, I’ll take the chatty and funny Cutter Slade over Gordan Freeman the stoic cipher any day.

Despite all of Appeal’s efforts to give Outcast appeal across the Atlantic Ocean by making it an English-first production, and despite a significant Stateside advertising campaign, it proved a hard sell in an American market where successful games were by now largely confined to a handful of hard-and-fast genres. It sold only about 50,000 copies in the United States after its release in the summer of 1999. Thankfully, it did considerably better in Europe, where it sold 350,000 copies. Combined with a relatively low final production bill — Sauer estimates that Appeal brought the whole game in for about €1.5 million, even with the cost of hiring an entire symphony orchestra and choir for a week — this total was enough to place the game right on the bubble between commercial failure and success.

After dithering for a while, Infogrames agreed to fund a sequel, on the condition that Appeal would make a version for the Sony PlayStation 2 as well as for personal computers, with more action and less adventure. That project muddled along for a little over a year, only to be cancelled by the publisher in 2001 as part of a program of corporate retrenching. Appeal shut down soon after, and that seemed to be that for Outcast.

Yet the game retained a warm place in the hearts of the three friends who had originally conceived it, as it did in those of a small but committed cult of fans, some of whom discovered it on abandonware sites only years after its release. Franck Sauer, Yves Grolet, and Yann Robert were eventually able to win back the rights to the game from their old publisher. In 2014, they made a lightly remastered version called Outcast 1.1; in 2017, they made a full-fledged remake called Outcast: Second Contact; in 2024, there came the long-delayed sequel, Outcast: A New Beginning. Being stuck in the ludic past as I am, I haven’t played any of these, but all have been fairly well-received by reviewers. Kudos to the creators and the fans for refusing to let a very special game die.

As for me, I’ll try to keep Outcast in mind the next time I’m tempted to pass judgment on a game without giving it an honest try. For games, like people, deserve to be judged on their own merits, not on the basis of their peer group.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Principals of Three-Dimensional Computer Animation (3rd ed.) by Michael O’Rourke and Outcast: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide by Joel Durham, Jr.; Computer Gaming World of November 1999; PC Format Gold of Winter 1997; PC Gamer of November 1997 and April 1998; Next Generation of January 1998; PC Games of December 1998.

Online sources include the old official Outcast site, an old unofficial Outcast fan site, a presentation given by the Appeal principals on Outcast’s graphics technology and aesthetics, a vintage “making of” documentary produced by Infogrames, an Adventure Classic Gaming interview with Doug Freese, a Game-OST interview with Lennie Moore, and a capsule biography of William Stromberg at Tribute Film Classics. Most of all, I drew from Franck Sauer’s home page, which is full of detailed stories and images from his long career in game development.

Where to Get It: There are two versions of Outcast available for digital purchase: the remastered Outcast 1.1 and the remade Outcast: Second Contact. If you buy the former, you gain access to the original 1999 version of the game — the one that I played for this article — as a “bonus goodie.” Should you decide to play this version, do note that it’s afflicted by one ugly glitch on newer machines, involving the lighthouse in the region of Okasankaar. (Strictly speaking, you don’t absolutely have to solve this puzzle to finish the game, but doing so does make it easier.) Your best bet is to make momentary use of the cheat mode when you find yourself needing to repair the lighthouse in a way that Lara Croft might approve of. On my computer at least, every other part of the game worked fine, the occasional bit of random graphical jank excepted.