From the beginning of this project, I’ve worked to remove the nostalgia factor from my writing about old games, to evaluate each game strictly on its own merits and demerits. I like to think that this approach has made my blog a uniquely enlightening window into gaming history. Still, one thing my years as a digital antiquarian have taught me is that you tread on people’s nostalgia at your peril. Some of what I’ve written here over the years has certainly generated its share of heat as well as light, not so much among those of you who are regular readers and commenters — you remain the most polite, thoughtful, insightful, and just plain nice readers any writer could hope to have — as among the ones who fire off nasty emails from anonymous addresses, who post screeds on less polite sites to which I’m occasionally pointed, or who offer up their drive-by comments right here every once in a while.

A common theme of these responses is that I’m not worthy of writing about this stuff, whether because I wasn’t there at the time — actually, I was, but whatever — or because I’m just not man enough to take my lumps and power through the really evil, unfair games. This rhetoric of inclusion and exclusion is all too symptomatic of the uglier sides of gaming culture. Just why so many angry, intolerant personalities are so attracted to computer games is a fascinating question, but must remain a question for another day. For today I will just say that, even aside from their ugliness, I find such sentiments strange. As far as I know, there’s zero street cred to be gained in the wider culture from being good at playing weird old videogames — or for that matter from being good at playing videogames of any stripe. What an odd thing to construct a public persona around. I’ve made a job out of analyzing old games, and even I sometimes want to say, “Dude, they’re just old games! Really, truly, they’re not worth getting so worked up over.”

That said, there do remain some rays of light amidst all this heat. It’s true that my experience of these games today — of playing them in a window on this giant monitor screen of mine, or playing them on the go on a laptop — must be in some fairly fundamental ways different from the way the same games were experienced all those years ago. One thing that gets obviously lost is the tactile, analog side of the vintage experience: handling the physical maps and manuals and packages (I now reference that stuff as PDF files, which isn’t quite the same); drawing maps and taking notes using real pen and paper (I now keep programs open in separate windows on that aforementioned giant monitor for those purposes); listening to the chuck-a-chunk of disk drives loading in the next bit of text or scenery (replacing the joy of anticipation is the instant response of my modern supercomputer). When I allow myself to put on my own nostalgia hat, just for a little while, I recognize that all these things are intimately bound up with my own memories of playing games back in the day.

And I also recognize that the discrepancies between the way I play now and the way I played back then go even further. Some of the most treasured of vintage games weren’t so much single works to be played and completed as veritable lifestyle choices. Ultima IV, to name a classic example, was huge enough and complicated enough that a kid who got it for Christmas in 1985 might very well still be playing it by the time Ultima V arrived in 1988; rinse and repeat for the next few entries in the series. From my jaded perspective, I wouldn’t brand any of these massive CRPGs as overly well-designed in the sense of being a reasonably soluble game to be completed in a reasonable amount of time, but then that wasn’t quite what most of the people who played them way back when were looking for in them. Actually solving the games became almost irrelevant for a kid who wanted to live in the world of Britannia.

I get that. I really do. No matter how deep a traveler in virtual time delves into the details of any era of history, there are some things he can never truly recapture. Were I to try, I would have to go away to spend a year or two disconnected from the Web and playing no other game — or at least no other CRPG — than the Ultima I planned to write about next. That, as I hope you can all appreciate, wouldn’t be a very good model for a blog like this one.

When I think in the abstract about this journey through gaming history I’ve been on for so long now, I realize that I’ve been trying to tell at least three intertwining stories.

One story is a critical design history of games. When I come to a game I judge worthy of taking the time to write about in depth — a judgment call that only becomes harder with every passing year, let me tell you — I play it and offer you my thoughts on it, trying to judge it not only in the context of our times but also in the context of its own times, and in the context of its peers.

A second story is that of the people who made these games, and how they went about doing so — the inevitable postmortems, as it were.

Doing these first two things is relatively easy. What’s harder is the third leg of the stool: what was it like to be a player of computer games all those years ago? Sometimes I stumble upon great anecdotes in this area. For instance, did you know about Clancy Shaffer?

In impersonal terms, Shaffer was one of the slightly dimmer stars among the constellation of adventure-game superfans — think Roe Adams III, Shay Addams, Computer Gaming World‘s indomitable Scorpia — who parlayed their love of the genre and their talent for solving games quickly into profitable sidelines if not full-on careers as columnists, commentators, play-testers, occasionally even design consultants; for his part, Shaffer contributed his long experience as a player to the much-loved Sir-Tech title Jagged Alliance.

Most of the many people who talked with Shaffer via post, via email, or via telephone assumed he was pretty much like them, an enthusiastic gamer and technology geek in his twenties or thirties. One of these folks, Rich Heimlich, has told of a time when a phone conversation turned to the future of computer technology in the longer view. “Frankly,” said Shaffer, “I’m not sure I’ll even be here to see it.” He was, he explained to his stunned interlocutor, 84 years old. He credited his hobby for the mental dexterity that caused so many to assume he was in his thirties at the oldest. Shaffer believed he had remained mentally sharp through puzzling his way through so many games, while he needed only look at the schedule of upcoming releases in a magazine to have something to which to look forward in life. Many of his friends who, like him, had retired twenty years ago were dead or senile, a situation Shaffer blamed on their having failed to find anything to do with themselves after leaving the working world behind.

Shaffer died in 2010 at age 99. Only after his passing, after reading his obituary, did Heimlich and other old computer-game buddies realize what an extraordinary life Shaffer had actually led, encompassing an education from Harvard University, a long career in construction and building management, 18 patents in construction engineering, an active leadership role in the Republican party, a Golden Glove championship in heavyweight boxing, and a long and successful run as a yacht racer and sailor of the world’s oceans. And yes, he had also loved to play computer games, parlaying that passion into more than 500 published articles.

But great anecdotes like this one from the consumption side of the gaming equation are the exception rather than the rule, not because they aren’t out there in spades in theory — I’m sure there have been plenty of other fascinating characters like Clancy Shaffer who have also made a passion for games a part of their lives — but because they rarely get publicized. The story of the players of vintage computer games is that of a huge, diffuse mass of millions of people whose individual stories almost never stretch beyond their immediate families and friends.

The situation becomes especially fraught when we try to zero in on the nitty-gritty details of how games were played and judged in their day. Am I as completely out of line as some have accused me of being in harping so relentlessly on the real or alleged design problems of so many games that others consider to be classics? Or did people back in the day, at least some of them, also get frustrated and downright angry at betrayals of their trust in the form of illogical puzzles and boring busywork? I know that I certainly did, but I’m only one data point.

One would think that the magazines, that primary link between the people who made games and those who played them, would be the best way of finding out what players were really thinking. In truth, though, the magazines rarely provided skeptical coverage of the games industry. The companies whose games they were reviewing were of course the very same companies that were helping to pay their bills by buying advertising — an obvious conflict of interest if ever there was one. More abstractly but no less significantly, there was a sense among those who worked for the magazines and those who worked for the game publishers that they were all in this together, living as they all were off the same hobby. Criticizing individual games too harshly, much less entire genres, could damage that hobby, ultimately damaging the magazines as much as the publishers. Thus when the latest heavily hyped King’s Quest came down the pipe, littered with that series’s usual design flaws, there was little incentive for the magazines to note that this monarch had no clothes.

So, we must look elsewhere to find out what average players were really thinking. But where? Most of the day-to-day discussions among gamers back in the day took place over the telephone, on school playgrounds, on computer bulletin boards, or on the early commercial online services that preceded the World Wide Web. While Jason Scott has done great work snarfing up a tiny piece of the online world of the 1980s and early 1990s, most of it is lost, presumably forever. (In this sense at least, historians of later eras of gaming history will have an easier time of it, thanks to archive.org and the relative permanence of the Internet.) The problem of capturing gaming as gamers knew it thus remains one without a comprehensive solution. I must confess that this is one reason I’m always happy when you, my readers, share your experiences with this or that game in the comments section — even, or perhaps especially, when you disagree with my own judgments on a game.

Still, relying exclusively on first-hand accounts from decades later to capture what it was like to be a gamer in the old days can be problematic in the same way that it can be problematic to rely exclusively on interviews with game developers to capture how and why games were made all those years ago: memories can fade, personal agendas can intrude, and those rose-colored glasses of nostalgia can be hard to take off. Pretty soon we’re calling every game from our adolescence a masterpiece and dumping on the brain-dead games played by all those stupid kids today — and get off my lawn while you’re at it. The golden age of gaming, like the golden age of science fiction, will always be twelve or somewhere thereabouts. All that’s fine for hoisting a beer with the other old-timers, but it can be worse than useless for doing serious history.

Thankfully, every once in a while I stumble upon another sort of cracked window into this aspect of gaming’s past. As many of you know, I’ve spent a couple of weeks over the last couple of years trolling through the voluminous (and growing) game-history archives of the Strong Museum of Play. Most of this material, hugely valuable to me though it’s been and will doubtless continue to be, focuses on the game-making side of the equation. Some of the archives, though, contain letters from actual players, giving that unvarnished glimpse into their world that I so crave. Indeed, these letters are among my favorite things in the archives. They are, first of all, great fun. The ones from the youngsters are often absurdly cute; it’s amazing how many liked to draw pictures to accompany their missives.

But it’s when I turn to the letters from older writers that I’m gratified and, yes, made to feel a little validated when I read that people were in fact noticing that games weren’t always playing fair with them. I’d like to share a couple of the more interesting letters of this type with you today.

We’ll begin with a letter from one Wes Irby of Plano, Texas, describing what he does and especially what he doesn’t enjoy in CRPGs. At the time he sent it to the Questbusters adventure-game newsletter in October of 1988, Irby was a self-described “grizzled computer adventurer” of age 43. Shay Addams, Questbusters’s editor, found the letter worthy enough to spread around among publishers of CRPGs. (Perhaps tellingly, he didn’t choose to publish it in his newsletter.)

Irby titles his missive “Things I Hate in a Fantasy-Role-Playing Game.” Taken on its own, it serves very well as a companion piece to a similar article I once wrote about graphic adventures. But because I just can’t shut up, and because I can’t resist taking the opportunity to point out places where Irby is unusually prescient or insightful, I’ve inserted my own comments into the piece; they appear in italics in the text that follows. Otherwise, I’ve only cleaned up the punctuation and spelling a bit here and there. The rest is Irby’s original letter from 1988.

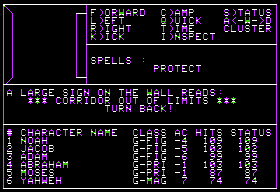

I hate rat killing!!! In Shard of Spring, I had to kill dozens of rats, snakes, kobolds, and bats before I could get back to the tower after a Wind Walk to safety. In Wizardry, the rats were Murphy’s ghosts, which I pummeled for hours when developing a new character. Ultima IV was perhaps the ultimate rat-killing game of all time; hour upon hour was spent in tedious little battles that I could not possibly lose and that offered little reward for victory. Give me a good battle to test my mettle, but don’t sentence me to rat killing!

Amen. The CRPG genre became the victim of an expectation which took hold early on that the games needed to be really, really long, needed to consume dozens if not hundreds of hours, in order for players to get their money’s worth. With disk space precious and memory space even more so on the computers of the era, developers had to pad out their games with a constant stream of cheap low-stakes random encounters to reach that goal. Amidst the other Interplay materials hosted at the Strong archive are several mentions of a version of Wasteland, prepared specially for testers in a hurry, in which the random encounters were left out entirely. That’s the version of Wasteland I’d like to play.

I hate being stuck!!! I enjoy the puzzles, riddles, and quests as a way to give some story line to the real heart of the game, which is killing bad guys. Just don’t give me any puzzles I can’t solve in a couple of hours. I solved Rubik’s Cube in about thirty hours, and that was nothing compared to some of the puzzles in The Destiny Knight. The last riddle in Knight of Diamonds delayed my completion (and purchase of the sequel) for nearly six months, until I made a call to Sir-Tech.

I haven’t discussed the issue of bad puzzle design in CRPGs to the same extent as I have the same issue in adventure games, but suffice to say that just about everything I’ve written in the one context applies equally in the other. Certainly riddles remain among the laziest — they require almost no programming effort to implement — and most problematic — they rely by definition on intuition and external cultural knowledge — forms of puzzle in either genre. Riddles aren’t puzzles at all really; the answer either pops into your head right away or it doesn’t, meaning the riddle turns into either a triviality or a brick wall. A good puzzle, by contrast, is one you can experiment with on your way to the correct solution. And as for the puzzles in The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight… much more on them a little later.

Perhaps the worst aspect of being stuck is the clue-book dilemma. Buying a clue book is demeaning. In addition, buying clue books could encourage impossible puzzles to boost the aftermarket for clue books. I am a reformed game pirate (that is how I got hooked), and I feel it is just as unfair for a company to charge me to finish the game I bought as it was for me to play the games (years ago) without paying for them. Multiple solutions, a la Might and Magic, are very nice. That game also had the desirable feature of allowing you to work on several things simultaneously so that being stuck on one didn’t bring the whole game to a standstill.

Here Irby brings up an idea I’ve also touched on once or twice: that the very worst examples of bad design can be read as not just good-faith disappointments but actual ethical lapses on the part of developers and publishers. Does selling consumers a game with puzzles that are insoluble except through hacking or the most tedious sort of brute-force approaches equate to breaching good faith by knowingly selling them a defective product? I tend to feel that it does.

As part of the same debate, the omnipresent clue books became a locus of much dark speculation and conspiracy theorizing back in the day. Did publishers, as Irby suggests, intentionally release games that couldn’t be solved without buying the clue book, thereby to pick up additional sales? The profit margins on clue books, not incidentally, tended to be much higher than that enjoyed by the games themselves. Still, the answer is more complicated than the question may first appear. Based on my research into the industry of the time, I don’t believe that any publishers or developers made insoluble games with the articulated motive of driving clue-book sales. To the extent that there was an ulterior motive surrounding the subject of clue books, it was that the clue books would allow them to make money off some of the people who pirated their games. (Rumors — almost certainly false, but telling by their very presence — occasionally swirled around the industry about this or that popular title whose clue-book sales had allegedly outstripped the number of copies of the actual game which had been sold.) Yet the fact does remain that even the hope of using clue books as a way of getting money out of pirates required games that would be difficult enough to cause many pirates to go out and buy the book. The human mind is a funny place, and the clue-book business likely did create certain almost unconscious pressures on game designers to design less soluble games.

I hate no-fault life insurance! If there is no penalty, there is no risk, there is no fear — translate that to no excitement. The adrenaline actually surged a few times during play of the Wizardry series when I encountered a group of monsters that might defeat me. In Bard’s Tale II, death was so painless that I committed suicide several times because it was the most expedient way to return to the Adventurer’s Guild.

When you take the risk of loss out of the game, it might as well be a crossword puzzle. The loss of possessions in Ultima IV and the loss of constitution in Might and Magic were tolerable compromises. The undead status in Phantasie was very nice. Your character was unharmed except for the fact that no further advancement was possible. Penalties can be too severe, of course. In Shard of Spring, loss of one battle means all characters are permanently lost. Too tough.

Here Irby hits on one of the most fraught debates in CRPG design, stretching from the days of the original Wizardry to today: what should be the penalty for failure? There’s no question that the fact that you couldn’t save in the dungeon was one of the defining aspects of Wizardry, the game that did more than any other to popularize the budding genre in the very early 1980s. Exultant stories of escaping the dreaded Total Party Loss by the skin of one’s teeth come up again and again when you read about the game. Andrew Greenberg and Bob Woodhead, the designers of Wizardry, took a hard-line stance on the issue, insisting that the lack of an in-dungeon save function was fundamental to an experience they had carefully crafted. They went so far as to issue legal threats against third-party utilities designed to mitigate the danger.

Over time, though, the mainstream CRPG industry moved toward the save-often, save-anywhere model, leaving Wizardry’s approach only to a hardcore sub-genre known as roguelikes. It seems clear that the change had some negative effects on encounter design; designers, assuming that players were indeed saving often and saving everywhere, felt they could afford to worry less about hitting players with impossible fights. Yet it also seems clear that many or most players, given the choice, would prefer to avoid the exhilaration of escaping near-disasters in Wizardry in favor of avoiding the consequences of unescaped disasters. The best solution, it seems to me, is to make limited or unlimited saving a player-selectable option. Failing that, it strikes me as better to err on the side of generosity; after all, hardcore players can still capture the exhilaration and anguish of an iron-man mode by simply imposing their own rules for when they allow themselves to save. All that said, the debate will doubtless continue to rage.

I hate being victimized. Loss of life, liberty, etc., in a situation I could have avoided through skillful play is quite different from a capricious, unavoidable loss. The Amulet of Skill in Knight of Diamonds was one such situation. It was not reasonable to expect me to fail to try the artifacts I found — a fact I soon remedied with my backup disk!!! The surprise attacks of the mages in Wizardry was another such example. Each of the Wizardry series seems to have one of these, but the worst was the teleportation trap on the top level of Wizardry III, which permanently encased my best party in stone.

Beyond rather putting the lie to some of Greenberg and Woodhead’s claims of having exhaustively balanced the Wizardry games, these criticisms again echo those I’ve made in the context of adventure games. Irby’s examples are the CRPG equivalents of the dreaded adventure-game Room of Sudden Death — except that in CRPGs like Wizardry with perma-death, their consequences are much more dire than just having to go back to your last save.

I hate extraordinary characters! If everyone is extraordinary then extraordinary becomes extra (extremely) ordinary and uninteresting. The characters in Ultima III and IV and Bard’s Tale I and II all had the maximum ratings for all stats before the end of the game. They lose their personalities that way.

This is one of Irby’s subtler complaints, but also I think one of his most insightful. Characters in CRPGs are made interesting, as he points out, through a combination of strengths and weaknesses. I spent considerable time in a recent article describing how the design standards of SSI’s “Gold Box” series of licensed Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs declined over time, but couldn’t find a place for the example of Pools of Darkness, the fourth and last game in the series that began with Pool of Radiance. Most of the fights in Pools of Darkness are effectively unwinnable if you don’t have “extraordinary” characters, in that they come down to quick-draw contests to find out whether your party or the monsters can fire off devastating area-effect magic first. Your entire party needs to have a maxed-out dexterity score of 18 to hope to consistently survive these battles. Pools of Darkness thus rewards cheaters and punishes honest players; it represents a cruel betrayal of players who had played through the entire series honestly to that point, without availing themselves of character editors or the like. CRPGs should strive not to make the extraordinary ordinary, and they should certainly not demand extraordinary characters that the player can only come by through cheating.

There are several more features which I find undesirable, but are not sufficiently irritating to put them in the “I hate” category. One such feature is the inability to save the game in certain places or situations. It is miserable to find yourself in a spot you can’t get out of (or don’t want to leave because of the difficulty in returning) at midnight (real time). I have continued through the wee hours on occasion, much to my regret the next day. At other times it has gotten so bad I have dozed off at the keyboard. The trek from the surface to the final set of riddles in Ultima IV takes nearly four hours. Without the ability to save along the way, this doesn’t make for good after-dinner entertainment. Some of the forays in the Phantasie series are also long and difficult, with no provision to save. This problem is compounded when you have an old machine like mine that locks up periodically. Depending on the weather and the phase of the moon, sometimes I can’t rely on sessions that average over half an hour.

There’s an interesting conflict here, which I sense that the usually insightful Irby may not have fully grasped, between his demand that death have consequences in CRPGs and his belief that he should be able to save anywhere. At the same time, though, it’s not an irreconcilable conflict. Roguelikes have traditionally made it possible to save anywhere by quitting the game, but immediately delete the save when you start to play again, thus making it impossible to use later on as a fallback position.

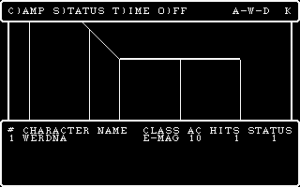

Still, it should always raise a red flag when a given game’s designers claim something which just happens to have been the easier choice from a technical perspective to have been a considered design choice. This skepticism should definitely be applied to Wizardry. Were the no-save dungeons that were such an integral part of the Wizardry experience really a considered design choice or a (happy?) accident arising from technical affordances? It’s very difficult to say this many years on. What is clear is that saving state in any sort of comprehensive way was a daunting challenge for 8-bit CRPGs spread over multiple disk sides. Wizardry and The Bard’s Tale didn’t really even bother to try; literally the only persistent data in these games and many others like them is the state of your characters, meaning not only that the dungeons are completely reset every time you enter them but that it’s possible to “win” them over and over again by killing the miraculously resurrected big baddie again and again. The 8-bit Ultima games did a little better, saving the state of the world map but not that of the cities or the dungeons. (I’ve nitpicked the extreme cruelty of Ultima IV’s ending, which Irby also references, enough on earlier occasions that I won’t belabor it any more here.) Only quite late in the day for the 8-bit CRPG did games like Wasteland work out ways to create truly, comprehensively persistent environments — in the case of Wasteland, by rewriting all of the data on each disk side on the fly as the player travels around the world (a very slow process, particularly in the case of the Commodore 64 and its legendarily slow disk drive).

Tedium is a killer. In Bard’s Tale there was one battle with 297 bersekers that always took fifteen or twenty minutes with the same results (this wasn’t rat-killing because the reward was significant and I could lose, maybe). The process of healing the party in the dungeon in Wizardry and the process of identifying discovered items in Shard of Spring are laborious. How boring it was in Ultima IV to stand around waiting for a pirate ship to happen along so I could capture it. The same can be said of sitting there holding down a key in Wasteland or Wrath of Denethenor while waiting for healing to occur. At least give me a wait command so I can read a book until something interesting happens.

I’m sort of ambivalent toward most aspects of mapping. A good map is satisfying and a good way to be sure nothing has been missed. Sometimes my son will use my maps (he hates mapping) in a game and find he is ready to go to the next level before his characters are. Mapping is a useful way to pace the game. The one irritating aspect of mapping is running off the edge of the paper. In Realms of Darkness mapping was very difficult because there was no “locater” or “direction” spell. More bothersome to me, though, was the fact that I never knew where to start on my paper. I had the same problem with Shard of Spring, but in retrospect that game didn’t require mapping.

Mapping is another area where the technical affordances of the earliest games had a major effect on their designs. The dungeon levels in most 8-bit CRPGs were laid out on grids of a consistent number of squares across and down; such a template minimized memory usage and simplified the programmer’s task enormously. Unrealistic though it was, it was also a blessing for mappers. Wizardry, a game that was oddly adept at turning its technical limitations into player positives, even included sheets of graph paper of exactly the right size in the box. Later games like Dungeon Master, whose levels sprawl everywhere, run badly afoul of the problem Irby describes above — that of maps “running off the edge of the paper.” In the case of Dungeon Master, it’s the one glaring flaw in what could otherwise serve as a masterclass in designing a challenging yet playable dungeon crawl.

I don’t like it when a program doesn’t take advantage of my second disk drive, and I would feel that way about my printer if I had one. I don’t like junk magic (spells you never use), and I don’t like being stuck forever with the names I pick on the spur of the moment. A name that struck my fancy one day may not on another.

Another problem similar to “junk magic” that only really began to surface around the time that Irby was writing this letter is junk skills. Wasteland is loaded with skills that are rarely or never useful, along with others that are essential, and there’s no way for the new player to identify which are which. It’s a more significant problem than junk magic usually is because you invest precious points into learning and advancing your skills; there’s a well-nigh irreversible opportunity cost to your choices. All of what we might call the second generation of Interplay CRPGs, which began with Wasteland, suffer at least somewhat from this syndrome. Like the sprawling dungeon levels in Dungeon Master, it’s an example of the higher ambitions and more sophisticated programming of later games impacting the end result in ways that are, at best, mixed in terms of playability.

I suppose you are wondering why I play these stupid games if there is so much about them I don’t like. Actually, there are more things I do like, particularly when compared to watching Gilligan’s Island or whatever the current TV fare is. I suppose it would be appropriate to mention a few of the things I do like.

In discussing the unavoidably anachronistic experience we have of old games today, we often note how many other games are at our fingertips — a luxury a kid who might hope to get one new game every birthday and Christmas most definitely didn’t enjoy. What we perhaps don’t address as much as we should is how much the entertainment landscape in general has changed. It can be a little tough even for those of us who lived through the 1980s to remember what a desert television was back then. I remember a television commercial — and from the following decade at that — in which a man checked into a hotel of the future, and was told that every movie ever made was available for viewing at the click of a remote control. Back then, this was outlandish science fiction. Today, it’s reality.

I like variety and surprises. Give me a cast of thousands over a fixed party anytime. Of course, the game designer has to force the need for multiple parties on me, or I will stick with the same group throughout because that is the best way to “win” the game. The Minotaur Temple in Phantasie I and the problems men had in Portsmouth in Might and Magic and the evil and good areas of Wizardry III were nice. More attractive are party changes for strategic reasons. What good are magic users in no-magic areas or a bard in a silent room? A rescue mission doesn’t need a thief and repetitive battles with many small opponents don’t require a fighter that deals heavy damage to one bad guy.

I like variety and surprises in the items found, the map, the specials encountered, in short in every aspect of the game. I like figuring out what things are and how they work. What a delight the thief’s dagger in Wizardry was! The maps in Wasteland are wonderful because any map may contain a map. The countryside contains towns and villages, the towns contain buildings, some buildings contain floors or secret passages. What fun!!!

I like missions and quests to pursue as I proceed. Some of these games are so large that intermediate goals are necessary to keep you on track. Might and Magic, Phantasie, and Bard’s Tale do a good job of creating a path with the “missions.” I like self-contained clues about the puzzles. In The Return of Heracles the sage was always there to provide an assist (for money, of course) if you got stuck. The multiple solutions or sources of vital information in Might and Magic greatly enhanced the probability of completing the missions and kept the game moving.

I like the idea of recruiting new characters, as opposed to starting over from scratch. In Galactic Adventures your crew could be augmented by recruiting survivors of a battle, provided they were less experienced than your leader. Charisma (little used in most games) could impact recruiting. Wasteland provides for recruiting of certain predetermined characters you encounter. These NPCs can be controlled almost like your characters and will advance with experience. Destiny Knight allows you to recruit (with a magic spell) any of the monsters you encounter, and requires that some specific characters be recruited to solve some of the puzzles, but these NPCs can’t be controlled and will not advance in level, so they are temporary members. They will occasionally turn on you, an interesting twist!!!

I like various skills, improved by practice or training for various characters. This makes the characters unique individuals, adding to the variety. This was implemented nicely in both Galactic Adventurers and Wasteland.

Eternal growth for my characters makes every session a little different and intriguing. If the characters “top out” too soon that aspect of the game loses its fascination. Wizardry was the best at providing continual growth opportunities because of the opportunity to change class and retain some of the abilities of the previous class. The Phantasie series seemed nicely balanced, with the end of the quest coming just before/as my characters topped out.

Speaking of eternal, I have never in all of my various adventures had a character retire because of age. Wizardry tried, but it never came into play because it was cheaper to heal at the foot of the stairs while identifying loot (same trip or short run to the dungeon for that purpose). Phantasie kept up with age, but it never affected play. I thought Might and Magic might, but I found the Fountain of Youth. The only FRPG I have played where you had to beat the clock is Tunnels of Doom, a simple hack-and-slash on my TI 99/4A that takes about ten hours for a game. Of course, it is quite different to spend ten hours and fail because the king died than it is to spend three months and fail by a few minutes. I like for time to be a factor to prevent me from being too conservative.

This matter of time affecting play really doesn’t fit into the “like” or the “don’t like” because I’ve never seen it effectively implemented. There are a couple of other items like that on my wish list. For example, training of new characters by older characters should take the place of slugging it out with Murphy’s ghost while the newcomers watch from the safety of the back row.

The placing of time limits on a game sounds to me like a very dangerous proposal. It was tried in 1989, the year after Irby wrote this letter, by The Magic Candle, a game that I haven’t played but that is quite well-regarded by the CRPG cognoscenti. That game was, however, kind enough to offer three difficulty levels, each with its own time limit, and the easiest level was generous enough that most players report that time never became a major factor. I don’t know of any game, even from this much crueler era of game design in general, that was cruel enough to let you play 100 hours or more and then tell you you’d lost because the evil wizard had finished conquering the world, thank you very much. Such an approach might have been more realistic than the alternative, where the evil wizard cackles and threatens occasionally but doesn’t seem to actually do much, but, as Sid Meier puts it, fun ought to trump realism every time in game design.

A very useful feature would be the ability to create my own macro consisting of a dozen or so keystrokes. Set up Control-1 through Control-9 and give me a simple way to specify the keystrokes to be executed when one is pressed.

Interestingly, this exact feature showed up in Interplay’s CRPGs very shortly after Irby wrote this letter, beginning with the MS-DOS version of Wasteland in March of 1989. And we do know that Interplay was one of the companies to which Shay Addams sent the letter. Is this a case of a single gamer’s correspondence being responsible for a significant feature in later games? The answer is likely lost forever to the vagaries of time and the inexactitude of memory.

A record of sorts of what has happened during the game would be nice. The chevron in Wizardry and the origin in Phantasie is the most I’ve ever seen done with this. How about a screen that told me I had 93 sessions, 4 divine interventions (restore backup), completed 12 quests, raised characters from the dead 47 times, and killed 23,472 monsters? Cute, huh?

Another crazily prescient proposal. These sorts of meta-textual status screens would become commonplace in CRPGs in later years. In this case, though, “later years” means much later. Thus, rather than speculating on whether he actively drove the genre’s future innovations, we can credit Irby this time merely with predicting them.

One last suggestion for the manufacturers: if you want that little card you put in each box back, offer me something I want. For example, give me a list of all the other nuts in my area code who have purchased this game and returned their little cards.

Enough of this, Wasteland is waiting.

With some exceptions — the last suggestion, for instance, would be a privacy violation that would make even the NSA raise an eyebrow — I agree with most of Irby’s positive suggestions, just as I do his complaints. It strikes me as I read through his letter that my own personal favorite among 8-bit CRPGs, Pool of Radiance, manages to avoid most of Irby’s pitfalls while implementing much from his list of desirable features — further confirmation of just what a remarkable piece of work that game, and to an only slightly lesser extent its sequel Curse of the Azure Bonds, really were. I hope Wes Irby got a chance to play them.

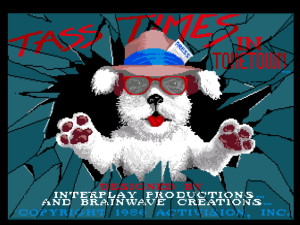

I have less to say about the second letter I’d like to share with you, and will thus present it without in-line commentary. This undated letter was sent directly to Interplay by its writer: Thomas G. Gutheil, an associate professor at the Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry, on whose letterhead it’s written. Its topic is The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight, a game I’ve written about only in passing but one with some serious design problems in the form of well-nigh insoluble puzzles. Self-serving though it may be, I present Gutheil’s letter to you today as one more proof that players did notice the things that were wrong with games back in the day — and that my perspective on them today therefore isn’t an entirely anachronistic one. More importantly, Gutheil’s speculations are still some of the most cogent I’ve ever seen on how bad puzzles make their way into games in the first place. For this reason alone, it’s eminently worthy of being preserved for posterity.

I am writing you a combination fan letter and critique in regard to the two volumes of The Bard’s Tale, of which I am a regular and fanatic user.

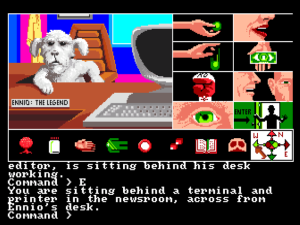

First, the good news: this is a TERRIFIC game, and I play it with addictive intensity, approximately an hour almost every day. The richness of the graphics, the cute depictions of the various characters, monsters, etc., and rich complexity and color of the mazes, tasks, issues, as well as the dry wit that pervades the program, make it a superb piece and probably the best maze-type adventure product on the market today. I congratulate you on this achievement.

Now, the bad news: the one thing I feel represents a defect in your program (and I only take your time to comment on it because it is so central) and one which is perhaps the only area where the Wizardry series (of which I am also an avid player and expert) is superior, is the notion of the so-called puzzles, a problem which becomes particularly noticeable in the “snares of death” in the second scenario. In all candor, speaking as an old puzzle taker and as a four-time grand master of the Boston Phoenix Puzzle Contest, I must say that these puzzles are simply too personal and idiosyncratic to be fair to the player. I would imagine you are doing a booming business in clue books since many of the puzzles are simply not accomplishable otherwise without hours of frustrating work, most of it highly speculative.

Permit me to try to clarify this point, since I am aware of the sensitive nature of these comments, given that I would imagine you regard the puzzles as being the “high art” of the game design. There should be an organic connection between the clues and the puzzles. For example, in Wizardry (sorry to plug the competition), there is a symbolic connection between the clue and its function. As one simplistic example, at the simplest level a bear statuette get you through a gate guarded by a bear, a key opens a particular door, and a ship-in-a-bottle item gets you across an open expanse of water.

Let me try to contrast this with some of the situations in your scenarios. You may recall that in one of the scenarios the presence of a “winged one” in the party was necessary to get across a particular chasm. The Winged One introduces himself to the party as one of almost a thousand individual wandering creatures that come and offer to join the party, to be attacked, or to be left in peace. This level of dilution and the failure to separate out the Winged One in some way makes it practically unrecallable much later on when you need it, particularly since there are several levels of dungeon (and in real life perhaps many interposing days and weeks) between the time you meet the Winged One (who does not stand out among the other wandering characters in any particular way) and the time you actually need him. Even if (as I do) you keep notes, there would be no particular reason to record this creature out of all. Moreover, to have this added character stuck in your party for long periods of time, when you could instead have the many-times more effective demons, Kringles, and salamanders, etc., would seem strategically self-defeating and therefore counter-intuitive for the normal strategy of game play AS IT IS ACTUALLY PLAYED.

This is my point: in many ways your puzzles in the scenarios seem to have been designed by someone who is not playing the game in the usual sequence, but designed as it were from the viewpoint of the programmer, who looks at the scenario “from above” — that is, from omniscient knowledge. In many situations the maze fails to take into account the fact that parties will not necessarily explore the maze in the predictable direct sequence you have imagined. The flow of doors and corridors do not appropriately guide a player so that they will take the puzzles in a meaningful sequence. Thus, when one gets a second clue before a first clue, only confusion results, and it is rarely resolved as the play advances.

Every once in a while you do catch on, and that is when something like the rock-scissors-paper game is invoked in your second scenario. That’s generally playing fair, although not everyone has played that game or would recognize it in the somewhat cryptic form in which it is presented. Thus the player does not gain the satisfaction of use of intellect in problem solving; instead, it’s the frustration of playing “guess what I’m thinking” with the author.

Despite all of the above criticism, the excitement and the challenge of playing the game still make it uniquely attractive; as you have no doubt caught on, I write because I care. I have had to actively fight the temptation to simply hack my way through the “snares of death” by direct cribbing from the clue books, so that I could get on to the real interest of the game, which is working one’s way through the dungeons and encountering the different items, monsters, and challenges. I believe that this impatience with the idiosyncratic (thus fundamentally unfair) design of these puzzles represents an impediment, and I would be interested to know if others have commented on this. Note that it doesn’t take any more work for the programmer, but merely a shift of viewpoint to make the puzzles relevant and fair to the reader and also proof against being taken “out of order,” which largely confuses the meaning. A puzzle that is challenging and tricky is fair; a puzzle that is idiosyncratically cryptic may not be.

Thank you for your attention to this somewhat long-winded letter; it was important to me to write. Given how much I care for this game and how devoted I am to playing it and to awaiting future scenarios, I wanted to call your attention to this issue. You need not respond personally, but I would of course be interested in any of your thoughts on this.

I conclude this article as a whole by echoing Gutheil’s closing sentiments; your feedback is the best part of writing this blog. I hope you didn’t find my musings on the process of doing history too digressive, and most of all I hope you found Wes Irby and Thomas Gutheil’s all too rare views from the trenches as fascinating as I did.