The line between entertainment and education at the Sierra of the early 1990s was much less clearly drawn among the design staff than it was in the company’s marketing materials. The exact same people who made the purely entertaining adventure games took up the task of making entries in Sierra’s new “Discovery Series” of educational games when that line made its debut in 1991. [1]The name “Discovery Series” wasn’t actually used until 1992. Before then, the earliest games in the series were sold simply as educational titles, without any further branding. Discounting for obvious reasons only the early-education titles, the results of their efforts could be every bit as satisfying for adults as they were for children and adolescents. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that much of the very best work done at Sierra during this period was done for the Discovery Series. The fact that they were designing games for a theoretical audience of youngsters seemed to prompt some of the staff to show a bit more kindness and mercy, to think about issues of playability in ways they sometimes couldn’t be bothered to do when making their other games. It’s thus a real shame that the Discovery Series tends to be overlooked by even many of the most ardent Sierra fans of today, who shy away instinctively from the educational label which Sierra’s marketers placed upon it. More or less educational these games may very well be, but many or most of them are also a hell of a lot of fun, whether you happen to be young, old, or somewhere in-between.

The inception of the Discovery Series was marked by a meeting of all of Sierra’s creative staff, aimed at drumming up ideas for educational games. One of the sample ideas which Ken Williams himself presented there was for something he called Mathemagical Mansion, a game whose player would have to solve math problems to explore ever deeper into the house in question. Programmer and game designer Corey Cole, who had recently created the first two titles in the adventure-game series Quest for Glory alongside his wife Lori Ann Cole, left the meeting having already decided to take the idea and run with it. He planned to expand on Ken Williams’s base by adding the character of a “Dr. Brain,” whom the player would need to impress in order to get a job working in his research laboratory. And he also planned to broaden the base of puzzle topics to include science, technology, and even a dash of culture to go along with the math problems. In additions to the merits of the original idea itself, practical and even political considerations prompted him to go this way. He knew that no new Quest for Glory game was in the cards for 1991, and he knew that, should his proposal not be accepted, he’d likely find himself working as a programmer on one of the educational proposals that had been. And, most importantly, he knew that Ken Williams would have a natural affinity for a proposal based on his own germ of an idea. His political calculus proved correct; after he showed a prototype demonstrating the basic interface and a few puzzles, Castle of Dr. Brain got the green light. His wife Lori, meanwhile, was similarly politically clever in proposing the early-education game Mixed-Up Fairy Tales, a pseudo-sequel to Roberta Williams’s Mixed-Up Mother Goose, and was also rewarded with a gig as lead designer on her own Discovery Series project.

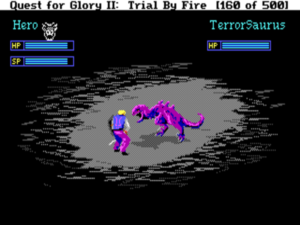

Corey and Lori Ann Cole didn’t need to up their design standards for their latest projects in the way that some of their colleagues would for other Discovery Series titles; the two Quest for Glory games they had already made were, in this reviewer’s opinion anyway, the absolute best adventures to come out of Sierra to this point. So, they only needed to continue to hew to the high standard they had already set.

Nevertheless, Castle of Dr. Brain represented a leap into unexplored territory in more ways than one for Corey. Lori had taken the lead on many aspects of the Quest for Glory games. The overall arc of the planned four-game series, drawn up before any implementation began on the first game, had been largely her vision, as had been much of the detail of plot and character within the two games that had been produced to date. While Lori had thus played the “artistic” role, Corey had been the puzzle guy, nailing down the details of what the player had to do and where she had to do it. But now, for the first time, he wouldn’t have Lori’s talents to lean on; Castle of Dr. Brain was all his baby. He comforted himself with the knowledge that it was to be at bottom just a big box of puzzles — and if there was one thing he felt he knew, it was puzzles. His attitude toward the project thus gradually moved from trepidation to exhilaration. By the time the game was finished, he would finally feel, as he put it to me many years later, “like a real game designer.”

Which isn’t to say that Castle of Dr. Brain was an easy game to make. The label on the box says that it’s designed for children aged twelve and up, implying that some sort of rigorous pedagogic methodology had gone into that formulation. In later years, certainly, any software from a major publisher daring to bill itself as “educational” would likely be approved if not designed by genuine educators, by people familiar with current age-appropriate curricula and theories of learning and all the rest. But Sierra back in those days just winged it. “While they aren’t intended to be hardcore educational products,” explained the brand manager for the Discovery Series, “they’re more than just games. They have legitimate academic content” — whatever “legitimate academic content” meant. Corey talked to exactly no education professionals in the course of making his educational game, unless you count his wife, who had worked as a schoolteacher years ago. Subject matter as well as pedagogic technique were left entirely up to him. He had promised Ken Williams a game that would have some math in it along with lots of other vaguely defined “educational” things. He got to decide what those things would be for himself.

Instead of some mythical stereotype of late childhood found only inside pedagogic textbooks, Corey aimed his game at the twelve-year-old self he remembered. Perhaps, he mused, he was unusually well-equipped to speak to bright kids of the sort he had once been. He remembered when, back at university, someone had passed an essay he had written through a computerized text analyzer, and the program had said that he wrote on a seventh-grade reading level. “That’s great!” said the analyzer’s programmer by way of comforting a Corey Cole whose first reaction was embarrassment. “You’ve written this so any adult or high-school student can understand it. Most people think they need to sound clever or sophisticated, but all they accomplish is to make their work inaccessible.” One of the worst sins would-be writers of children’s and young-adult fiction can commit is to write down to their target audience; youngsters can smell such condescension a mile away. It seemed that Corey would, at the very least, be free of that sin.

All of which was well and good, but it still left the matter of the actual puzzles to be sorted out. Corey had always loved books of puzzles and brainteasers, and had had this love in mind when he first pitched his idea for Castle of Dr. Brain. Maybe, he had thought, such books could even provide him with most of the puzzles he would need. Yet that proved not to be the case when the time came to roll up his sleeves and start making his game. Corey:

The puzzle books were useless. A book advertising “over 60 puzzles and brainteasers” typically had four formats, and 15 puzzles in each format. They might have cryptograms, crossword puzzles, and grid puzzles (“Who lives in the purple house? What’s their job, hobby, and favorite food?”). Most of these are weak in a computer game, and I wanted to have a dozen or more unique puzzles.

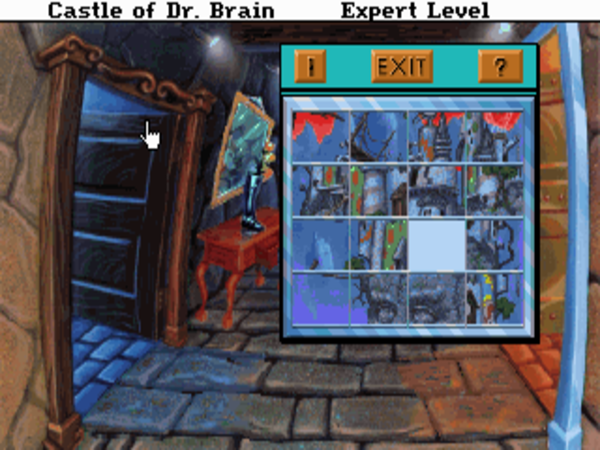

Corey wound up creating groupings of puzzles on the various subjects he chose, clustering them together in rooms of Dr. Brain’s castle. First came three math problems, then three puzzles dealing with time. And so on and so on, incorporating among others a word-puzzle room, a robotics-and-computers room, even an astronomy room — all adding up to 24 multifarious puzzles in all. The puzzle books may have proved a dead end, but some of the puzzles that made their way into the game are nevertheless variations on old favorites of one type or another, such as Mastermind, Hangman, and Knights and Knaves. Roughly half of the puzzles, though, are indeed completely original. Unsurprisingly, these are the ones that tend to make the most impact, to the point of being at least vaguely remembered by some old players of Castle of Dr. Brain literally decades after they last saw them.

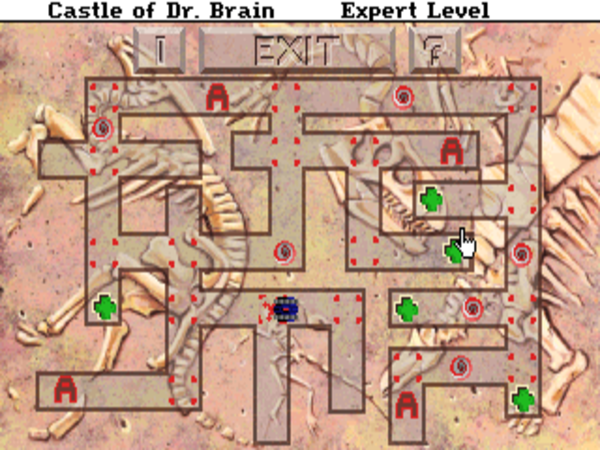

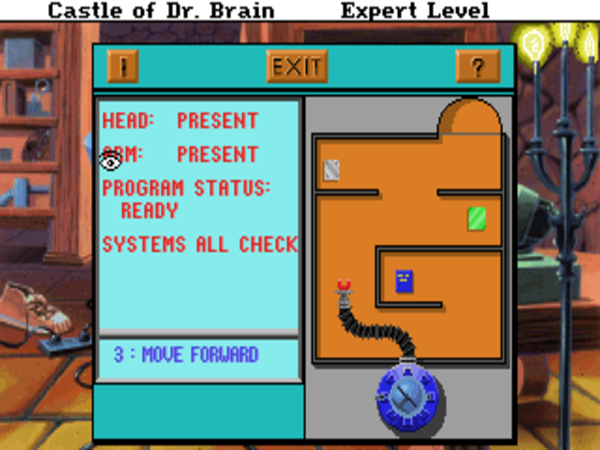

The robot maze that’s shown above, for instance, is a marvel of elegant, minimalist design, played in real time to make it exciting for youngsters (and oldsters) raised on videogames. You need to collect cards from all of the red “A” symbols by running the little blue robot over them, while avoiding the swirling red-and-purple vortexes, which will swallow it up. Running over the green crosses, meanwhile, will toggle various vortexes off, thus making them safe to travel over, and on, thus making them decidedly unsafe. The robot will always move straight ahead, until it encounters an obstacle in the form of a wall, which will cause it to turn around and go back whence it came. But there is one exception to this rule, an exception that also happens to be the only way you can interact with the puzzle: you can click on any of the intersections marked with four red dots to cause the robot to turn right when it reaches that intersection; click again to turn off this “traffic signal.” And that’s it. From one verb is created a hugely intriguing possibility space.

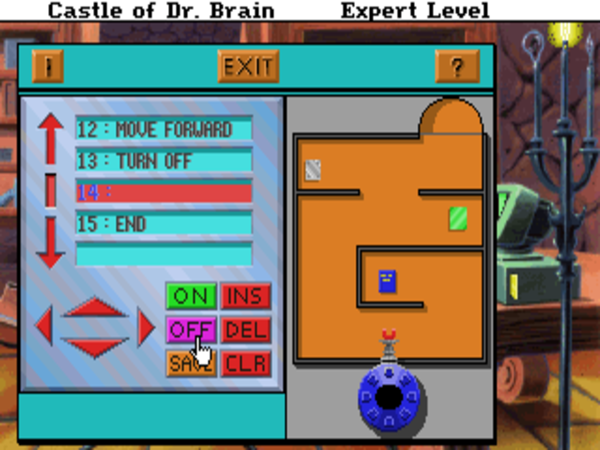

But most beloved of all might just be the robot-programming puzzle. You need to retrieve certain items out of a locked cabinet by writing a program to move a robot arm through the correct sequence of steps. Besides being a brilliantly original and entertaining puzzle in its own right, it’s also a fine introduction to the joy of programming.

To make Castle of Dr. Brain accessible to as wide an audience as possible, Corey Cole implemented three difficulty levels, which the player can change at any time to adjust for those types of puzzles she’s better or worse at. The “expert” level of any given puzzle should offer an enjoyable challenge to almost any adult, while the “novice” level is good even for many children who are younger than the game’s stated minimum age of twelve. Yet Corey didn’t settle for this form of adjustable difficulty alone. He also came up with a mechanic for “puzzle coins” which ties into your final score in the game. You earn coins by completing puzzles, and can then trade them in for hints if a later puzzle has you stumped. Your final score will take a hit in doing so, but this only adds a bit of replayability to a game that’s really not all that long.

The puzzle design constitutes much of what makes the finished game great, but the puzzles aren’t quite the sum total of the experience. Being made using an engine designed first and foremost for adventure games, and by a company and a designer known first and foremost for same, Castle of Dr. Brain is an embodied experience rather than an exercise in purely abstract puzzling. The plot isn’t up to much — “solve puzzles to move through the castle until you meet Dr. Brain and he gives you a job” is all it consists of from beginning to end — but, hey, it’s there. The charming old coot himself even pops up from time to time to offer encouragement. A stronger line connecting Castle of Dr. Brain to the Quest for Glory adventure games in particular comes in the form of the plethora of optional gags and Easter eggs in every area of the castle. You can click on almost anything and get a reaction. From the front door on which you can pound instead of ringing the doorbell to the telephone you can pick up in the good doctor’s inner sanctum, the game is a riot of interactivity, just as any good adventure game should be, paying full attention to what designer Bob Bates calls the “else” of the “if, then, else” logic of adventure design. And Castle of Dr. Brain is full of the same horrid puns and general good nature which mark the Quest for Glory games. I don’t believe Corey Cole is capable of making a game that’s less than thoroughly likable.

Within the framework of adventure lent by the SCI engine, however, Castle of Dr. Brain and its sequel are unique among the Discovery Series — in fact, unique among Sierra’s adventures in general — for a certain spirit of formal innovation. Those other Discovery games mostly look and play like standard Sierra adventures of their time; it’s just that their puzzles and plots are aimed at an ostensibly younger audience. But, perhaps because Corey was himself an experienced SCI programmer, Castle of Dr. Brain dared to shake up the status quo. Replacing the third-person view and visible onscreen avatar of the typical Sierra adventure is a first-person viewpoint. And then, too, the protagonist here goes unnamed and uncharacterized; the protagonist, in other words, is meant to be you. There is much to be said for both third-person and first-person approaches to the graphical adventure, just as there is for both the richly characterized adventure-game protagonist and the “nameless, faceless adventurer” of Zork. For today, I will only say that the choices Corey made here — both departing from the norm at Sierra — strike me as eminently correct for the game he wanted to make and the audience he wanted to reach. To be constantly switching between a third-person “exploration mode” and a series of screen-filling set-piece puzzles would have felt jarring. And then, too, children love nothing better than to imagine themselves inside their entertainments.

So, Corey Cole had good reason to feel proud of the finished game. Proud he was — and is: he still describes Castle of Dr. Brain as the most satisfying single project of his career. And Sierra too had reason to be pleased after the game was released: it became by far the most commercially successful of all the Discovery Series. Corey estimates that it sold over 100,000 copies in its initial full-price form, then another 150,000 copies as a budget re-release. Those numbers were almost comparable to what might be expected from a new Space Quest or Leisure Suit Larry — flashier games with much bigger development budgets. Sierra’s accountants thus couldn’t help but see Castle of Dr. Brain as a bargain, a relatively cheap investment that had made them quite a lot of money.

With numbers like those, and with the series-loving Ken Williams running Sierra, a sequel was inevitable. Corey was ready and eager to helm that project, but he wasn’t given a fair chance to do so. After Castle of Dr. Brain was finished, he was moved back to the programmer’s role he had been able to avoid for a while by making it, assigned the task of porting Sierra’s SCI engine to the Sega Genesis videogame console. He was offered the “opportunity” to design the sequel strictly as a moonlighting project, if he was willing to give up the 1-percent royalty he had received on the first game in favor of a small lump-sum payment. Understandably, he turned down an offer that would have consumed his nights and weekends for many months to come for very little financial reward. The task of designing the sequel was instead handed to one Patrick Bridgemon, a technical writer who had been responsible for many Sierra manuals and hint books, but whose only experience to date working on the games proper had consisted of a polishing-up of the writing in the first Police Quest game for a recent point-and-click remake of same.

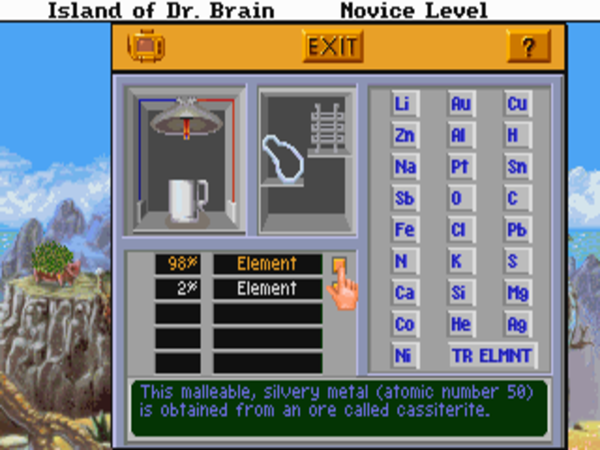

Given these circumstances, one would rather expect the game that became known as The Island of Dr. Brain to disappoint. And, indeed, the general critical consensus over the years has tended to paint it as something of a pale shadow of its illustrious predecessor. In this case, though, I find myself in disagreement with the consensus; I don’t think that The Island of Dr. Brain fares badly at all in comparison to its predecessor. Yes, some of the puzzles are cribbed directly from the previous game, and, yes, more old chestnuts do make an appearance; the game’s lowlight is definitely the supremely tedious (is there any other kind?) Tower of Hanoi puzzle. Yet there are also a number of completely original puzzles here which can stand proudly alongside the best puzzles from the earlier game. And, once again, the vast majority of the puzzles, whether original or cribbed, are great fun to solve.

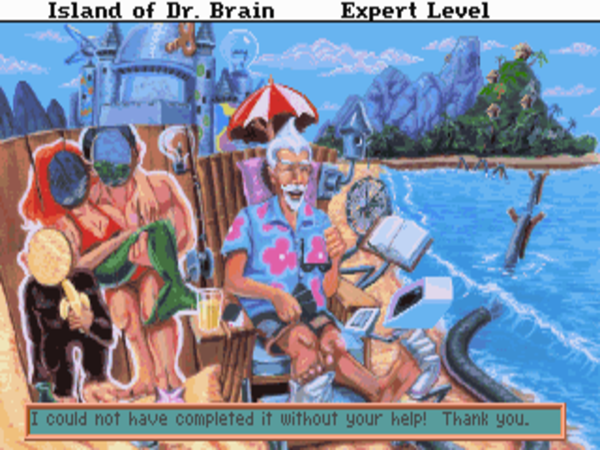

There’s a bit more to the plot this time around. Someone has knocked the good doctor over the head — with a pink-flamingo lawn ornament, no less! — and absconded with his most powerful and dangerous invention. In practice, however, the plot still doesn’t really matter all that much. Now duly hired as Dr. Brain’s assistant, you’ve been sent to your boss’s private island to retrieve a vital battery that’s necessary to stop the evil one’s dastardly plan. But you can’t just walk in and pick it up; you have to solve puzzles in order to make your way to the center of the island where the battery lies waiting. As security systems go, this one doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, but there you go. The real point, of course, is the puzzles.

It should be amply clear by now that Bridgemon, doubtless responding to dictates from his managers, adopted a “don’t fix what isn’t broken” approach to the sequel. Still, he did manage to innovate modestly within the established framework. This time out, the puzzles and their solutions are all randomized to one degree or another, thus addressing the most obvious complaint customers who had spent $40 or more on the first game might have made: the fact that it just wasn’t very long at all. The Island of Dr. Brain even sets up a sort of meta-challenge for the truly hardcore. If you solve all 26 puzzles four times on each of the three difficulty levels (!), without using any of your hint coins, you earn the maximum of 1000 points, and are rewarded with a special picture. I can’t say that I can muster up that much dedication today, but it’s easy to imagine a patient youngster taking on the challenge, and thereby getting many, many hours out of the game.

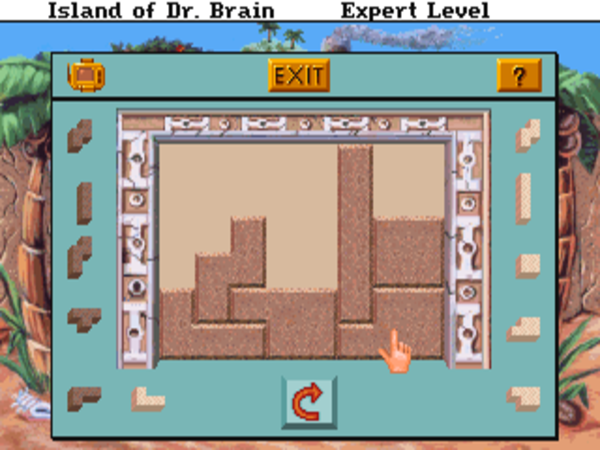

Playing with polynominoes. Eat your heart out, Alexey Pajitnov.

Likewise, the sequel not only embraces its predecessor’s wide range of educational themes but actually expands upon it. Puzzles in The Island of Dr. Brain often deal with the expected: mathematics, spatial logic, computer programming (the logic-gates puzzle is every bit as good as Corey Cole’s programming puzzles from the previous game). At the same time, though, Bridgemon shows no fear of the humanities, despite the latter being a field of knowledge so much less obviously suited to puzzles. The Island of Dr. Brain finds clever ways to dive into foreign languages, musical notation, even masterpieces of literature and the visual arts. One of my favorite puzzles teaches you to identify the works of great artists, from Vincent van Gogh to Jackson Pollock, by their unique styles.

The sequel shipped with an “EncycloAlmanacTionaryOgraphy” in the box, a 104-page book full of information that’s sometimes useful for solving the puzzles but is more often there just to add depth to the topics the puzzles cover. As its name would imply, it’s a glorious mess, a big splat of completely unrelated data — a random cross-section of some tiny portion of all the sheer stuff the human race has learned and done and achieved over the centuries. I love it.

The Island of Dr. Brain didn’t do quite as well as its predecessor had commercially, but sold well enough that these two games would not mark the end of Dr. Thaddeus Egghead Brain’s puzzling career. The second game would be, however, the last of the series to be developed by Sierra in-house. Later entries were given to Bright Star Technology, a developer specializing in educational software which Sierra acquired in 1992 as part of Ken Williams’s general educational push. Those Dr. Brain games — there were five more of them in all, stretching all the way to 1999 — are slicker productions in many ways, but lack their predecessors’ gonzo spirit. They’re just well-made educational products — no more, no less.

Which only leads me to emphasize once again what a pleasure these first two Dr. Brain games still are to play. The EncycloAlmanacTionaryOgraphy nicely illustrates the overarching Dr. Brain take on education. In a world obsessed with specialists and specialties, these games dare to tell us that knowledge in general is a sumptuous banquet which is only made more exciting through variety. A person, they imply, should feel free to become a computer programmer and a poet, a geneticist and a musician. At the risk of offending the many hard-working pedagogues out there, I can’t help but think that much of the reason these particular educational games are so bracing is because of the lack of a formal disciplinarian to say, “No, you can’t follow up a mechanical-engineering problem with an art-appreciation exercise. The child will be confused by such an abrupt shift and will fail to internalize the lessons. Such disparate subject matters should be separated by a reasonable pause, and are best contained in separate software programs designed for the individual needs of disparate educational models….” blah, blah, blah. Just throw it all in there, I say, and let children (and adults) enjoy drinking from the fire hose. I often think that half the modern world’s dysfunction is due to the fact that we’ve all become so specialized — so segregated — that we don’t know how to talk to one another anymore. I believe that we desperately need more Renaissance people, more jacks of all trades, even if that means fewer masters of one. The Dr. Brain games, it would appear, agree with me.

If we set aside the educational aspect and consider the Dr. Brain games purely as puzzle collections, they do suffer in some ways in comparison to The Fool’s Errand, the game I still consider the standard by which all other puzzlers should be measured. The Dr. Brain games were created at the dawn of the age of multimedia computing, when Sierra even more so than most companies was determined to put in every bit of digitized sound and color they could fit onto a reasonable number of floppy disks. Such rather garish presentations perhaps haven’t aged as well as The Fool’s Errand‘s austere, elegant black-and-white look. And the Dr. Brain games lack anything like The Fool’s Errand‘s dazzling structural complexity; structurally, they’re just a collection of standalone puzzles, to be solved one at a time until you solve the last one and win. But of course, all of these alleged negatives could equally be read as positives. Certainly the audiovisuals of Dr. Brain have plenty of goofy charm of their own, and you may very well have more room in your life for a casual series of discrete puzzles than for the all-consuming obsession that The Fool’s Errand can become once you’ve fallen down its rabbit hole.

Unlike many of the Sierra titles from their era, the Discovery Series has never been officially re-released as digital downloads — doubtless thanks once again to that dreaded “educational” tag. Yet they richly deserve to be remembered and, most of all, to be played. I’m therefore going to take the liberty of offering Castle of Dr. Brain and The Island of Dr. Brain for download here. As usual, I’ve included a configuration file that will make them as easy as possible to get running with the aid of DOSBox, whether you’re using a Windows, Macintosh, or Linux machine. Happy puzzling!

(My huge thanks go to Corey Cole, who took the time to correspond with me at length on this phase of his career. Be sure to check out Hero-U: From Rogue to Redemption, a new game in the spirit of the Quest for Glory series which Corey and Lori Ann Cole have created. As of this writing, its release is expected in a matter of weeks.

Other sources include the issues of Sierra’s official magazine from Fall 1991, Fall 1992, and Winter 1992.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The name “Discovery Series” wasn’t actually used until 1992. Before then, the earliest games in the series were sold simply as educational titles, without any further branding. |

|---|