In 1825, in Paris, France, a man named Charles-Louis Havas set up an agency to translate foreign news reports into French for the benefit of local newspapers. At that time, his country along with the rest of the Western world stood on the cusp of far-reaching changes. Over the next few decades, the railroad and the telegraph remade travel and communications in their image. This led in turn to the rise of consumerism, as exemplified by the opening of Le Bon Marché Rive Gauche, the world’s first big-box department store, in Paris in 1852. And with consumerism came mass-market advertising, a practice which was to a large extent invented in France.

The Havas Agency rode this wave of change adroitly. Charles-Louis Havas’s two sons, who took over the company after their father’s death, reoriented it toward advertising, making it into the dominant power in the field in France. Havas went public in 1879. During the twentieth century, it expanded into tourism and magazine and book publishing, and eventually into cable television, via Canal+, by far the most popular paid television channel in France from 1984 until the arrival of Netflix in that market in 2014.

The creation of Canal+ marked the point where Havas first became intertwined with another many-tendriled French conglomerate: the Compagnie Générale des Eaux, or CGE. The name translates to “The General Water Company.” As it would imply, CGE had gotten its start when modern plumbing was first spreading across France, all the way back in 1853. It later expanded into other types of urban service, from garbage collection to parking to public transportation. Veering still further out of its original lane, CGE invested enough into Canal+ to be given a 15-percent stake in the nascent channel in 1983, marking the start of a new era for the formerly staid provider of utility services. Over the next fifteen years, its growth outstripped that of Havas dramatically, as it became a major player in cable television, in film and television production, in telecommunications and wired and cellular telephony.

By 1997, CGE had acquired a 29.3-percent stake in Havas as well. In May of the following year, it completed the process of absorption. The new entity abandoned the anachronistic reference to water and became known as Vivendi, a far catchier name that can be roughly translated as “Of Life” or “About Life.” Having expanded by now to the point that it was running out of obvious growth opportunities inside France, it looked beyond the borders of its homeland. In the next few years, it would buy up a wide cross-section of foreign media.

This impulse to grow put the software arm of Cendant Corporation on Vivendi’s hit list just as soon as Henry Silverman, that troubled American company’s boss, made it clear that said division was on the market. For, of all sectors of media, gaming seemed set for the most explosive growth of all, and Vivendi was eager to grab a chunk of that action. It was not alone in this: a deregulation of the French telecommunications industry that had been completed on January 1, 1998, was spawning a foreign feeding frenzy among actual and would-be French game publishers. Conglomerates like Ubisoft, Titus, and Infogrames would soon join Vivendi as new household words among American gamers. The days of the “French Touch” being the mark of games that were sometimes charmingly, sometimes infuriatingly off-kilter would fade into the past, as French publishers would come to stand behind some of the biggest mass-market hits in the field.

Seen through this prism, there can be no doubt about the main reason Vivendi chose to take Cendant’s games division off Henry Silverman’s hands: Blizzard Entertainment, whose games Warcraft 2, Diablo, and Starcraft had combined with the Battle.net matchmaking service to become a literal modus vivendi for millions of loyal acolytes. For its part, Sierra was on the verge of scoring a massive, long overdue hit of its own with Half-Life, but that had not yet come to pass as negotiations were taking place. As matters currently stood, Sierra was merely the additional baggage which Vivendi had to accept in order to get its hands on Blizzard.

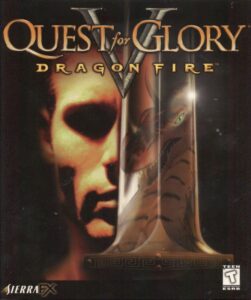

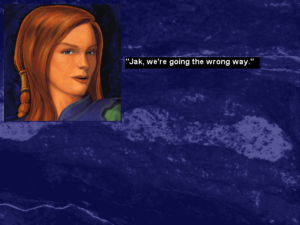

The deal was done with remarkable speed. On November 20, 1998 — one day after the release of Half-Life, four days before the release of King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity, and eighteen days before that of Quest for Glory V: Dragon Fire — it was announced that the now-former Cendant software division had become a new subsidiary of the Vivendi empire, under the name of Havas Interactive. The price? A cool $1 billion in cash — cash that was, needless to say, much-needed by the beleaguered Cendant. The current Cendant software head David Grenewetzki, who as far as the French financiers could see had done a pretty good job so far of cutting fat and improving efficiency, would be allowed to continue to do so as the first boss of Havas Interactive.

The folks in Oakhurst had been through such a roller-coaster ride already that they were by now almost numb to further surprises. First had come the acquisition by CUC and the sidelining of Ken Williams, who looked a lot less like a soulless fat cat in comparison to what came after him. Then the merger with HFS, then the shock and horror of the revelations of accounting fraud and the plummeting share price, which had cost some staffers dearly — especially the ones who had signed onto the plan to replace some of their salary with Cendant stock. Al Lowe of Leisure Suit Larry fame, for example, says that almost overnight he and his wife lost “the equivalent of a really nice home.” So, the news of this latest sale, to yet another company that no one had ever heard of, was greeted mostly with resigned shrugs. Everyone had long since learned just to take it day by day, to hope for the best and to try to ignore the little voice inside that was telling them that they probably ought to be expecting the worst.

For three months, sanguinity seemed justified; not much changed. Then came February 22, 1999.

The first sign the Oakhurst employees encountered that something was out of the ordinary on that Monday morning were a few Pinkerton Security vans that they saw parked in front of the building as they arrived at work. Not knowing what else to do, they shrugged and went about their usual start-of-the-week routines. An all-hands meeting was scheduled for that morning at the movie theater next door, the latest installment in a longstanding quarterly tradition of same. If anyone felt a premonition of danger — the mass layoff of 1994 had been announced at another of these meetings, at the same theater — no one voiced their concerns. Instead everyone shuffled in in the standard fashion, swapping stories about the weekend just passed and other inter-office scuttlebutt, a little impatient as always with this corporate rigamarole, eager to get back to their desks and get back to work making games.

They soon learned that they would not be making games in Oakhurst, today or ever again. The instant they had all taken their places, the axe fell — or rather the chainsaw, as it would later be dubbed by Scott Murphy, a designer of Sierra’s Space Quest series. The Oakhurst office was closing, the staffers were told matter-of-factly. While they were still struggling to process this piece of information, they were each handed an envelope with their name on it. Inside was a short note, telling them whether they had just lost their job entirely or whether they were being offered the opportunity to relocate to the Bellevue office, to continue making games there.

As of February of 1999, Yosemite Entertainment had three major projects in development; in an indubitable sign of the changing times in gaming, none was an adventure game. One was a “space simulator” in the mold of Wing Commander and TIE Fighter, based in this case on the Babylon 5 television series; one was an MMORPG, a far more ambitious successor to The Realm that was to take place in J.R.R. Tolkien’s world of Middle-earth; and one was a shooter powered by the Unreal engine that was being created in consultation with a former Navy SEAL commander. The first two projects were to resume production in Bellevue; the last was cancelled outright.

When all of the support staff who are needed to run an office like this one were added to the chopping block, the number of people who lost their jobs that day came to almost 100 — almost two-thirds of the total number of Sierra employees remaining in Oakhurst. The ranks of the newly jobless also included a small team that had been working with Corey and Lori Ann Cole to make an expansion pack for Quest for Glory V, which was to add to the base game some form of the multiplayer support that had once been the whole thrust of the project as well as some new single-player content.

Sierra’s new management had left nothing to chance. While the meeting had been taking place at the theater, the Pinkerton hired guns had been changing the security codes that employees used to access the office building. The victims of the layoff were now led inside in small groups under armed guard, where they were permitted just a few minutes to clean their personal belongings out of their desks.

The shock of it all can hardly be overstated. No one had seen this coming; even Craig Alexander, the manager of Yosemite Entertainment, had been given no more than a few minutes warning on the morning of the layoff itself. With cataclysmic suddenness, the largest employer in Oakhurst had simply ceased to be. Come the day after Chainsaw Monday, the old office building and its previously bustling parking lot looked like a movie set after hours. The only people left to roam the halls were a few support personnel for The Realm, whose servers were to remain in Oakhurst for lack of anyplace better to put them while Havas Interactive sought a buyer for the building and if possible the MMORPG as well. (The Realm had just enough players that its new mother corporation hesitated to piss them off by shutting it down, but neither did Havas Interactive want to invest any real money in a virtual world built around the creaky old SCI engine.)

As an ironic capstone to the brutal proceedings in Oakhurst, both the Babylon 5 game and the Middle-earth MMORPG were themselves cancelled just six months later in Bellevue, as part of another round of “reorganizing.” The folks who had relocated to a big city 1000 miles further up the coast to continue these projects learned that the joke was on them, as they were left high and dry there in Seattle. The emerging new business model for Sierra was that of a publisher and distributor of games only, not an active developer of them. In other words, Sierra was deemed by Vivendi to be of further use only as a recognizable brand name, not as a coherent ongoing creative enterprise. Had he been paying attention, Henry Silverman, Wall Street’s king of outsourcing and branding, would surely have approved.

In the years that followed, surprisingly few of the prominent names who had built Sierra’s original brand, that of the biggest adventure-games studio on the planet, continued to work in the industry. What with the diminished state of the adventure game in general, the skill sets of people like them just weren’t so much in demand anymore.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole did find employment in the industry at least intermittently, but did so in roles that no longer got their names featured on box covers. Corey worked as a consultant on such unlikely projects as Barbie: Fashion Pack Games (to which he contributed a Space Invaders clone that replaced spaceships and laser guns with hearts and lipstick). Both Corey and Lori Ann worked on a virtual world called Explorati, which, had it ever come to fruition, might have been the missing link between Habitat and Second Life. Later, Corey worked on online-poker sites. Eventually, the Coles did come home again, to make Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption, which is Quest for Glory VI in all but name, and the more modestly scaled but equally warm-hearted Summer Daze: Tilly’s Tale. Corey told me recently that he and Lori Ann have some other ideas in the pipeline that might come to fruition someday, but he also told me that they “are pushing 70, and spending more time on ourselves.” Which is more than fair enough, of course.

Embracing the spirit of the late 1990s, when you couldn’t toss a dead rat into the air without hitting five different dot.com startups, Ken Williams initially envisioned a second act for his career, as an Internet entrepreneur. He passed up a chance to get in on the ground floor with Jeff Bezos’s Amazon.com in favor of a venture of his own called TalkSpot, which aimed to bring talk radio online. Born, one senses, largely out of Ken’s longstanding infatuation with Rush Limbaugh, a hard-right AM-radio provocateur of the old school, TalkSpot can nevertheless be read as prescient if you squint at it just right, a harbinger of the podcasts that were still to come. But it was just a little bit too far out in front of the nation’s telecommunications infrastructure; almost everyone was still accessing the Internet over dial-up at the time, which made even audio-only streaming a well-nigh insurmountable challenge. An attempted pivot from being a public-facing provider of online talk radio to providing streaming services to other companies, under the name of WorldStream, couldn’t overcome this reality, and the company closed up shop — ironically, not all that long before the DSL lines that might have made it sustainable started to roll out across the country.

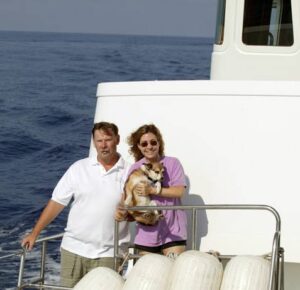

Then again, it may be that Ken Williams’s heart was never really in it. Realizing that he had achieved his lifelong dream of becoming rich — he had all the money that he, Roberta, and their children could ever possibly need — he didn’t become a third-time entrepreneur. Instead he and Roberta threw themselves into an active and enviable early retirement. They sailed a boat all over the world, blogging about their travels to a whole new audience who often knew nothing about their previous lives. “We somehow achieved a second fifteen minutes of fame as world cruisers and explorers,” writes Ken in his memoir, exaggerating only slightly.

In 2023, they made a belated return to game development, via a graphical remake of the game that had started it all, for them as for so many others: Will Crowther and Don Woods’s original Adventure. It struck many as an odd choice, given the rich well of beloved Sierra intellectual property from which they might have drawn instead, but it seemed that they wanted above all to pay tribute to the game that had first prompted them to create their seminal Mystery House all those years ago, and to create Sierra On-Line in order to sell it. Having accomplished that mission, they have no plans to make more games.

And as for little Oakhurst, California, the strangest place at which anyone ever decided to found a games company: it weathered the turbulence of Sierra’s departure surprisingly well in the end, as it had so many changes before. There was a brief flicker of hope that game development might again become a linchpin of the town’s economy when, about six months after Chainsaw Monday, the British publisher Codemasters bought Sierra’s old facility, along with The Realm and its servers and the rights to the Navy SEAL game that had been cancelled when the chainsaw fell. Codemasters tried to assemble a team in Oakhurst to complete the SEAL game, which would seem to have been as prescient as Ken Williams’s TalkSpot in its way, anticipating the craze for military-themed shooters that would be ignited by Medal of Honor: Allied Assault in 2002. But most of the people who had once worked on the project had already left town, and Codemasters had trouble attracting more to such a rural location. The winds of corporate politics are fickle; within barely six months, the SEAL game was cancelled a second and final time, the Realm servers were finally moved out, and the now-empty building was put up for sale once again. These events marked the definitive end of game development in Oakhurst, barring the contracting jobs that the Coles did out of their house.

The loss was a serious blow to the local economy in the short term. But, luckily for Oakhurst, Yosemite National Park abides. After a brief-lived dip, the town started to grow again, thanks to the tourists who were now streaming through the “Gateway to Yosemite” in greater numbers than ever. Oakhurst’s population as of the 2020 American census was just shy of 6000 souls — twice the number counted by the 2000 census, when the community was still reeling from Sierra’s departure.

Today, then, Sierra On-Line’s sixteen-year stay in Oakhurst has gone down in local lore as just one more anecdote involving the eccentric outsiders who have always been drawn to the place. Still, among the hordes of families and hardcore hikers who pass through, one can sometimes spot a different breed of middle-aged tourist, who arrives brimming with nostalgia for a second-hand past he or she knew only through the pictures and articles in Sierra’s newsletters. Such is the nature of time. What is passed but remembered, if only by a few, becomes history.

I’d like to share with you a eulogy for Sierra — one that you may very well have seen before, written by someone far closer to all of this than I am. Josh Mandel was a writer and designer who worked at Sierra for several years. Just three days after Chainsaw Monday, he wrote the following.

On Monday, the last vestige of the original Sierra On-Line was laid to rest in Oakhurst, California. That branch, renamed “Yosemite Entertainment,” was shuttered on February 22nd, putting most of its 125-plus employees out of work.

You may not care for what Sierra has become since the days when dozens of unpretentious parser-driven graphic adventures flowed, seemingly effortlessly, out of Oakhurst. But there’s no denying that, back then, Sierra On-Line was the life’s blood of the adventure-game industry.

Maybe the games were a little more rough-hewn than those of its competitors — not that there were many competitors at that point. But Sierra kept adventure gamers happy and fed, gamers who would’ve otherwise starved to death on the arguably more polished, but frustratingly infrequent, releases of Lucasfilm Games (as they were once called).

Sierra alone grew the industry in other ways, too. It was Ken Williams who, almost single-handedly, created the market for PC sound hardware by vigorously educating the public [on] the AdLib card and, shortly thereafter, the breathtaking Roland MT-32. He supported those cards in style while other publishers wanted nothing to do with them. It was Corey and Lori Cole who invented the first true hybrid, replayable adventure/RPG. It was Christy Marx’s lump-in-the-throat ending to Conquests of Camelot that reminded us that not every computer game had to have a group hug at the end. It was Mark Crowe and Scott Murphy who made us want to kill off our onscreen alter ego, to see what inventive, gooey death had been anticipated for us. It was Roberta, before anyone else, who invented strong female heroines. It was Al Lowe, bringing up the rear (literally and figuratively) by creating Leisure Suit Larry, the most popular, pirated game of its decade. We knew this because we sold far more Larry hint books than we sold of the actual software.

It was the Sierra News Magazine (later InterAction) that let us feel like we knew the people making these games, that they were a family-run business, staffed by people who lived an isolated life, surrounded by idyllic, ageless beauty and creating games that were a labor of love. That was, at least for a while, an accurate picture. This was a family we wanted to feel a part of, for good reason, and people came from thousands of miles away to take a tour and see how real it all was…

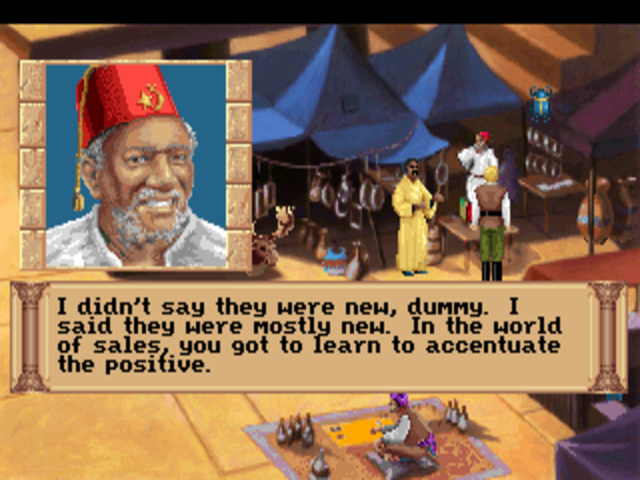

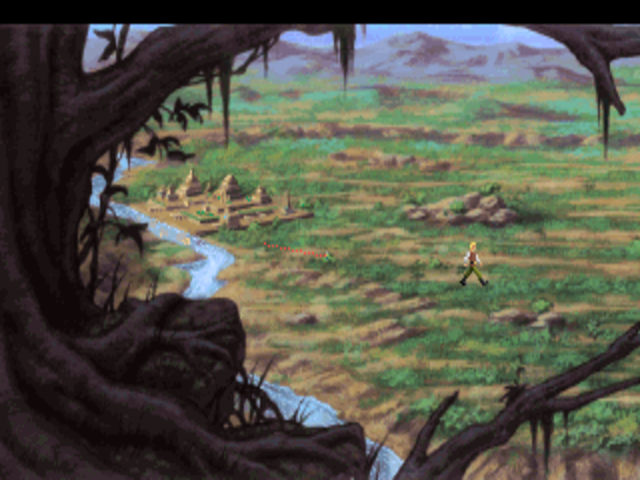

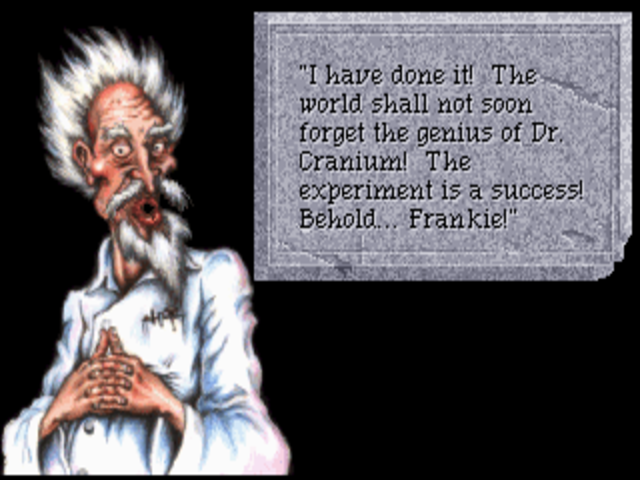

Some may argue that Sierra lives on in Bellevue, Washington, where Al Lowe, Jane Jensen, Roberta Williams, Mark Seibert, and a handful of [other] Oakhurst refugees still labor diligently on games side-by-side with scores of newer talent. But games like King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity and Leisure Suit Larry 7 have a distinctly different flavor than the seat-of-the-pants, funny, touching adventures that Oakhurst once produced. They are commercial.

Invariably, in a company that grows the way Sierra grew, innovation gives way to emulation. Whereas Sierra’s management once strove to make it solid, profitable, and yet fun, they now strive to dominate other companies, force annual growth in the double digits, and (like so many other companies) cut jobs mercilessly to improve the bottom line and thrill the stockholders. Yet the Ghost of Sierra Past still walked the halls in Oakhurst. The rooms were adorned with the art of glories past, the artists and programmers who helped to create those glories were, in fair measure, still living and working there. Now that spirit has been exorcised by scrubbed, glad-handing executives who don’t know, or don’t care, what those artists and programmers could do when they were motivated and well-managed.

People, living and working closely together in the pursuit of shared joy, were what made Sierra games great. Thank you, Ken, for creating something utterly unique, something warm, fun, and beautiful. Damn you, Ken, for allowing others to tear it down.

Whether you were a Sierra fan or not, we are all diminished by the loss of history, talent, and continuity within the gaming industry. Rest in peace, Sierra On-Line.

The skeptical historian in me hastens to state that this eulogy is very sentimentalized; whatever else they may have been, Sierra’s games were always at least trying to be deeply commercial, as Ken Williams will happily tell you today if you ask him. On the other hand, though, it’s rather in the nature of eulogies to be sentimental, isn’t it? This one is not without plenty of wise truths as well. And among its truths is its willingness to acknowledge that Sierra’s games “were a little more rough-hewn than those of its competitors.”

I, for one, have definitely spent more time over the years complaining about the rough edges in Sierra’s adventure games than I have praising their strong points. I’ve occasionally been accused of ungraciousness in this regard, even of having it in personally for Ken and Roberta Williams. The latter has never been the case, but, looking back, I can understand why it might have seemed that way sometimes, especially in the early years of this site.

Throughout most of the 1980s, the yin and yang of adventure gaming were Infocom and Sierra, each manifesting a contrasting philosophy. As Ken Williams himself has put it, Infocom was “literary,” while Sierra was “mass-market.” One Infocom game looked exactly the same as any other; they were all made up of nothing but text, after all. But Sierra’s games were, right from the very start, the products of Ken’s “ten-foot rule”: meaning that they had to be so audiovisually striking that a shopper would notice them running on a demo machine from ten feet away and rush over to find out more. (It may seem impossible to imagine today that a game with graphics as rudimentary as those of, say, The Wizard and the Princess could have such an effect on anyone, but trust me when I say that, in a time when no other adventure game had any graphics at all, these graphics were more exciting than any ultra-HD wonder is to a jaded modern soul.) Infocom had to prioritize design and writing, because design and writing were all they had. Sierra had other charms with which to beguile their customers. It’s no great wonder that today, when those other charms have ceased to be so beguiling, Infocom’s games tend to hold up much better.

But I’m not here to play the part of an old Infocom fanboy with a bad case of sour grapes. (Whatever we can say about their respective games today, there’s no doubt which company won the fight for hearts and minds in the 1980s…) I actually think a comparison between the two is useful in another way. Infocom was always a collective enterprise, an amalgamation of equals that came into being behind an appropriately round conference table in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Strong personalities though the principals may have been, one cannot say that Infocom was ever Al Vezza’s company or Joel Berez’s company, nor Dave Lebling’s or Marc Blank’s. From first to last, it was a choir of voices, if sometimes a discordant one. Compare this to Sierra: there wasn’t ever an inch of daylight between that company and Ken and Roberta Williams. Sierra’s personality was theirs. Sierra’s strengths were theirs. And, yes, Sierra’s weaknesses, the same ones I’ve documented at so much length over the years, were theirs as well.

I’ll get to their strengths — no, really, I will, I promise — but permit me to dwell on their weaknesses just a little bit longer before I do so. I think that these mostly come down to one simple fact: that neither Ken nor Roberta Williams was ever really a gamer. Ken has admitted that the only Sierra game he ever sat down and played to completion for himself, the way that his customers did it, was SoftPorn — presumably because it was so short and easy (not to mention it being so in tune with where Ken’s head was at in the early 1980s). In his memoir, Ken writes that “to me, Sierra was a marketing company. Lots of people can design products, advertise products, and sell products. But what really lifted Sierra above the pack was our marketing.” Here we see his blasé attitude toward design laid out in stark black and white: “lots of people” can do it. A talent for marketing, it seems, is rarer, and thus apparently more precious. (As for the rest of that sentence: I’m afraid you’ll have to ask Ken how “marketing” is different from “advertising” and “selling…”)

Roberta has not made so explicit a statement on the subject, but it does strike me as telling that, when she was given her choice of any project in the world recently, she chose to remake Crowther and Woods’s Adventure. That game was, it would seem, a once-in-a-lifetime obsession for her.

Needless to say, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with not being a gamer; there are plenty of other hobbies in this world that are equally healthy and stimulating and satisfying, or quite possibly more so. Yet not being a gamer can become an issue when one is running a games company or designing games for a living. At some very fundamental level, neither Ken nor Roberta had any idea what it was like to experience the products Sierra made. And because they didn’t know this, they also didn’t know how important design is to that experience — didn’t understand that, while the ten-foot rule applies for only a limited window of time, writing and puzzles and systems are timeless. Infocom scheduled weekly lunches for everyone who wished to attend to discuss the nature of good and bad design at sometimes heated length, drafted documents full of guidelines about same, made design the cornerstone of their culture. As far as I can tell, discussions of this nature never took place at Sierra. Later, after Infocom was shuttered, LucasArts picked up the torch, publicizing Ron Gilbert’s famous manifesto on “Why Adventure Games Suck” — by “adventure games,” of course, he largely meant “Sierra adventure games” — and including a short description of its design philosophy in every single game manual. Again, such a chapter is unimaginable in a Sierra manual.

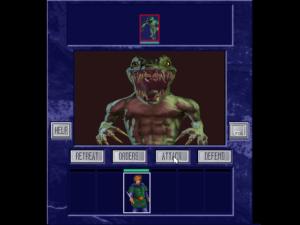

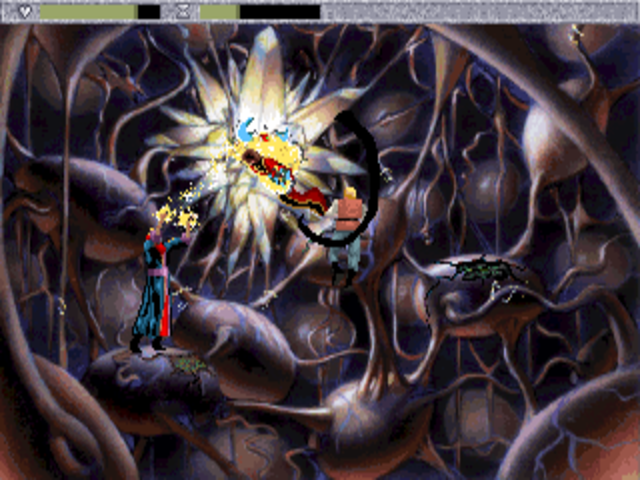

For, like everything else associated with the company, Sierra’s games reflected the personalities of Ken and Roberta Williams. They were better at the big picture than they were at the details; they were flashy, audacious, and technologically cutting-edge on the surface, and all too often badly flawed underneath. Those Sierra designers who were determined to make good games, by seeking the input of outside testers and following other best practices, had to swim against the tide of the company’s culture in order to do so. Not that many of them were willing or able to put in the effort when push came to shove, although I have no doubt that everyone had the best of intentions. The games did start to become a bit less egregiously unfair in the 1990s, by which time LucasArts’s crusade for “no deaths and no dead ends” had become enough of a cause célèbre to shame Sierra’s designers as well into ceasing to abuse their players so flagrantly. Nevertheless, even at this late date, Sierra’s games still tended to combine grand concepts with poor-to-middling execution at the level of the granular details. If I’m hard on them, this is the reason why: because they frustrate me to no end with the way they could have been so great, if only Ken Williams had instilled a modicum of process at his company to make them so.

Having said that, though, I have to admit as well that Ken and Roberta Williams are probably deserving of more praise than I’ve given them over the fifteen years I’ve been writing these histories; it’s not as if they were the only people in games with blind spots. Contrary to popular belief, Roberta was not the first female adventure-game designer — that honor goes to Alexis Adams, wife of Scott Adams, who beat her to the punch by a year — but she was by far the most prominent woman in the field of game design in general for the better part of two decades, an inspiration to countless other girls and women, some of whom are making games today because of her. That alone is more than enough to ensure her a respected place in gaming history.

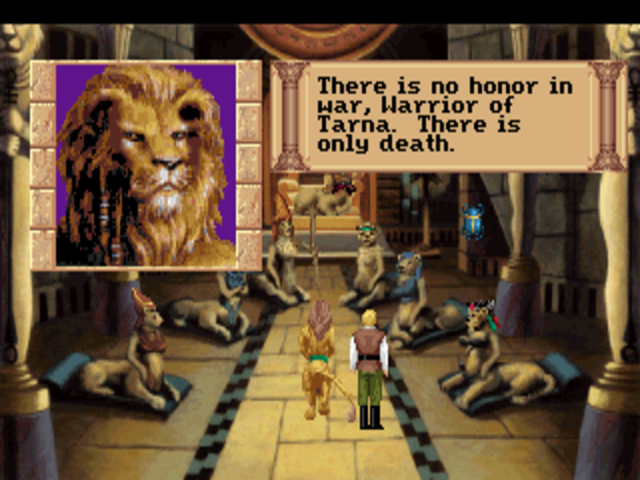

Meanwhile Sierra itself was a beacon of diversity in an industry that sometimes seemed close to a mono-culture, the sole purview of a certain stripe of nerdy young white man with a sharply circumscribed range of cultural interests. The people behind Sierra’s most iconic games came from everywhere but the places and backgrounds you might expect. Al Lowe was a music teacher; Gano Haine was a social-studies teacher; Christy Marx was a cartoon scriptwriter; Jim Walls was a police officer; Jane Jensen and Lorelei Shannon were aspiring novelists; Mark Crowe was a visual artist; Scott Murphy was a short-order cook; Corey and Lori Ann Cole were newsletter editors and publishers and tabletop-RPG designers; Josh Mandel was a standup comedian; Roberta Williams, of course, was a homemaker. At one point in the early 1990s, fully half of Sierra’s active game-development projects were helmed by women. You would be hard-pressed to find a single one at any other studio.

This was the positive side of Ken Williams’s mass-market vision — the one which said that games were for everyone, and that they could be about absolutely anything. There was no gatekeeping at Sierra, in any sense of the word. For all of LucasArts’s thoughtfulness about design, it seldom strayed far from its comfort zone of cartoon-comedy graphic adventures. Sierra, by contrast, dared to be bold, thematically and aesthetically as well as technologically. I may have a long list of niggly complaints about a game like, say, Jane Jensen’s Gabriel Knight: The Beast Within, but I’ll never forget it either. Despite all of its infelicities, it dares to engage with aspects of life that are raw and tragic and real, giving rise to emotions in this player at least that are the opposite of trite. How many of its contemporaries from companies other than Sierra can say the same?

And as went the production side of the business, so went the reception side. Perhaps ironically because he wasn’t a gamer himself, perhaps just because one doesn’t get to be Walt Disney by selling to a niche audience, Ken understood that computer games had to become more accessible if they were ever to make a sustained impact beyond the core demographic of technically proficient young men. He strove mightily on multiple fronts to make this happen. Very early in his time as the head of Sierra, he was instrumental in setting up distribution systems to ensure that computer games were readily available all over the United States, the way that a new form of consumer entertainment ought to be. (Few Sierra fans are aware that it was Ken who founded SoftSel, the dominant American consumer-software distributor of the 1980s and beyond, in order to ensure that Sierra’s games and those of others had a smoothly paved highway to retail stores. Doing so may have been his most important single contribution of all from a purely business perspective.) A little later, he put together easy-to-assemble “multimedia upgrade kits” for everyday computers, and made sure that Sierra’s software installers were the most user-friendly in the business, asking you for IRQ and DMA numbers only as a last resort. If some of his ideas about interactive movies as the future of mainstream entertainment proved a bit half-baked in the long run, other Sierra games like The Incredible Machine more directly anticipated the “Casual Revolution” to come. If his wide-angle vision of gaming seemed increasingly anachronistic in the latter 1990s, even if it was wrong-headed in a hundred particulars, the fact was that it would come roaring back and win the day in the broader strokes. His only real mistake was that of leaving the industry which he had done so much to build a little bit too early to be vindicated.

So, let us wave a fond farewell to Ken and Roberta Williams as they sail off into the sunset, and give them their full measure of absolution from the petty carping of critics like me as we do so. In every sense of the words, Ken and Roberta were pioneers and visionaries. Their absence from these histories will be keenly felt. Godspeed and bon voyage, you two. Your certainly made your presence felt while you were with us.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line by Ken Williams and Vivendi: A Key Player in Global Entertainment and Media by Philippe Bouquillion.

Online sources include “How Sierra was Captured, Then Killed, by a Massive Accounting Fraud” by Duncan Fyfe at Vice, “Chainsaw Monday (Sierra On-Line Shuts Down)” at Larry Laffer Dot Net, Ken Williams’s page of thoughts and rambles at Sierra Gamers, and an old TalkSpot interview with some of Sierra’s employees, done just after the second round of lay-offs hit Bellevue.

I also made use of the materials held in the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. And once again I owe a debt of gratitude to Corey Cole for answering my questions about this period at his usual thoughtful length.