No one on their deathbed ever said, “I wish I had spent more time alone with my computer!”

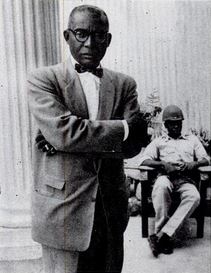

— Dani Bunten Berry

If you ever want to feel old, just talk to the younger generation.

A few years ago now, I met the kids of a good friend of mine for the very first time: four boys between the ages of four and twelve, all more or less crazy about videogames. As someone who spends a lot of his time and earns a lot of his income writing about games, I arrived at their house with high expectations attached.

Alas, I’m afraid I proved a bit of a disappointment to them. The distance between the musty old games that I knew and the shiny modern ones that they played was just too far to bridge; shared frames of reference were tough to come up with. This was more or less what I had anticipated, given how painfully limited I already knew my knowledge of modern gaming to be. But one thing did genuinely surprise me: it was tough for these youngsters to wrap their heads around the very notion of a game that you played to completion by yourself and then put on the shelf, much as you might a book. The games they knew, from Roblox to Fortnite, were all social affairs that you played online with friends or strangers, that ended only when you got sick of them or your peer group moved on to something else. Games that you played alone, without at the very least leader boards and achievements on-hand to measure yourself against others, were utterly alien to them. It was quite a reality check for me.

So, I immediately started to wonder how we had gotten to this point — a point not necessarily better or worse than the sort of gaming that I knew growing up and am still most comfortable with, just very different. This series of articles should serve as the beginning of an answer to that complicated question. Their primary focus is not so much how computer games went multiplayer, nor even how they first went online; those things are in some ways the easy, obvious parts of the equation. It’s rather how games did those things persistently — i.e., permanently, so that each session became part of a larger meta-game, if you will, embedded in a virtual community. Or perhaps the virtual community is embedded in the game. It all depends on how you look at it, and which precise game you happen to be talking about. Whichever way, it has left folks like me, whose natural tendency is still to read games like books with distinct beginnings, middles, and ends, anachronistic iconoclasts in the eyes of the youthful mainstream.

Which, I hasten to add, is perfectly okay; I’ve always found the ditch more fun than the middle of the road anyway. Still, sometimes it’s good to know how the other 90 percent lives, especially if you claim to be a gaming historian…

“Persistent online multiplayer gaming” (POMG, shall we say?) is a mouthful to be sure, but it will have to do for lack of a better descriptor of the phenomenon that has created such a divide between myself and my friend’s children. It’s actually older than you might expect, having first come to be in the 1970s on PLATO, a non-profit computer network run out of the University of Illinois but encompassing several other American educational institutions as well. Much has been written about this pioneering network, which uncannily presaged in so many of its particulars what the Internet would become for the world writ large two decades later. (I recommend Brian Dear’s The Friendly Orange Glow for a book-length treatment.) It should suffice for our purposes today to say that PLATO became host to, among other online communities of interest, an extraordinarily vibrant gaming culture. Thanks to the fact that PLATO games lived on a multi-user network rather than standalone single-user personal computers, they could do stuff that most gamers who were not lucky enough to be affiliated with a PLATO-connected university would have to wait many more years to experience.

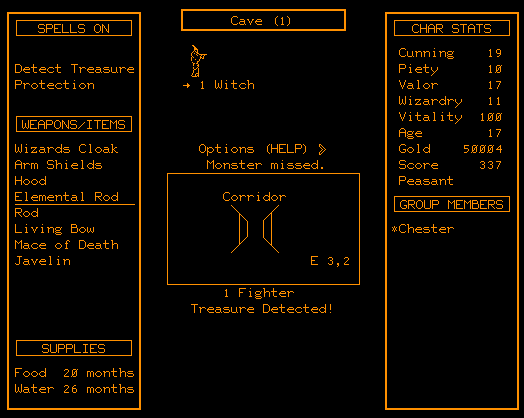

The first recognizable single-player CRPGs were born on PLATO in the mid-1970s, inspired by the revolutionary new tabletop game known as Dungeons & Dragons. They were followed by the first multiplayer ones in amazingly short order. Already in 1975’s Moria,[1]The PLATO Moria was a completely different game from the 1983 single-player roguelike that bore the same name. players met up with their peers online to chat, brag, and sell or trade loot to one another. When they were ready to venture forth to kill monsters, they could do so in groups of up to ten, pooling their resources and sharing the rewards. A slightly later PLATO game called Oubliette implemented the same basic concept in an even more sophisticated way. The degree of persistence of these games was limited by a lack of storage capacity — the only data that was saved between sessions were the statistics and inventory of each player’s character, with the rest of the environment being generated randomly each time out — but they were miles ahead of anything available for the early personal computers that were beginning to appear at the same time. Indeed, Wizardry, the game that cemented the CRPG’s status as a staple genre on personal computers in 1981, was in many ways simply a scaled-down version of Oubliette, with the multiplayer party replaced by a party of characters that were all controlled by the same player.

Chester Bolingbroke, better known online as The CRPG Addict, plays Moria. Note the “Group Members” field at bottom right. Chester is alone here, but he could be adventuring with up to nine others.

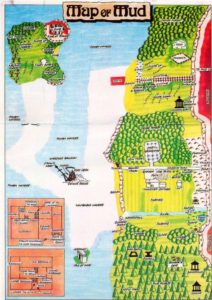

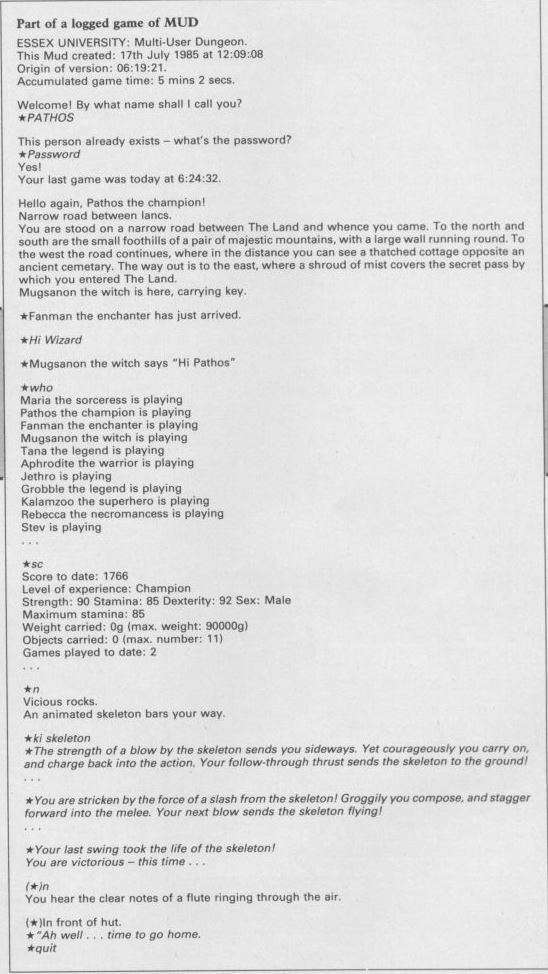

A more comprehensive sort of persistence arrived with the first Multi-User Dungeon (MUD), developed by Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle, two students at the University of Essex in Britain, and first deployed there in a nascent form in late 1978 or 1979. A MUD borrowed the text-only interface and presentation of Will Crowther and Don Woods’s seminal game of Adventure, but the world it presented was a shared, fully persistent one between its periodic resets to a virgin state, chockablock with other real humans to interact with and perhaps fight. “The Land,” as Bartle dubbed his game’s environs, expanded to more than 600 rooms by the early 1980s, even as its ideas and a good portion of its code were used to set up other, similar environments at many more universities.

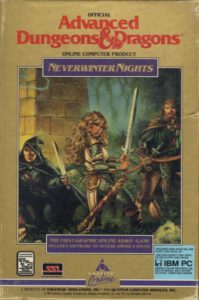

In the meanwhile, the first commercial online services were starting up in the United States. By 1984, you could, for the price of a substantial hourly fee, dial into the big mainframes of services like CompuServe using your home computer. Once logged in there, you could socialize, shop, bank, make travel reservations, read newspapers, and do much else that most people wouldn’t begin to do online until more than a decade later — including gaming. For example, CompuServe offered MegaWars, a persistent grand-strategy game of galactic conquest whose campaigns took groups of up to 100 players four to six weeks to complete. (Woe betide the ones who couldn’t log in for some reason of an evening in the midst of that marathon!) You could also find various MUDs, as well as Island of Kesmai, a multiplayer CRPG boasting most of the same features as PLATO’s Oubliette in a genuinely persistent world rather than a perpetually regenerated one. CompuServe’s competitor GEnie had Air Warrior, a multiplayer flight simulator with bitmapped 3D graphics and sound effects to rival any of the contemporaneous single-player simulators on personal computers. For the price of $11 per hour, you could participate in grand Air Warrior campaigns that lasted three weeks each and involved hundreds of other subscribers, organizing and flying bombing raids and defending against the enemy’s attacks on their own lines. In 1991, America Online put up Neverwinter Nights,[2]Not the same game as the 2002 Bioware CRPG of the same name. which did for the “Gold Box” line of licensed Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs what MUD had done for Adventure and Air Warrior had done for flight simulators, transporting the single-player game into a persistent multiplayer space.

All of this stuff was more or less incredible in the context of the times. At the same time, though, we mustn’t forget that it was strictly the purview of a privileged elite, made up of those with login credentials for institutional-computing networks or money in their pockets to pay fairly exorbitant hourly fees to feed their gaming habits. So, I’d like to back up now and tell a different story of POMG — one with more of a populist thrust, focusing on what was actually attainable by the majority of people out there, the ones who neither had access to a university’s mainframe nor could afford to spend hundreds of dollars per month on a hobby. Rest assured that the two narratives will meet before all is said and done.

POMG came to everyday digital gaming in the reverse order of the words that make up the acronym: first games were multiplayer, then they went online, and then these online games became persistent. Let’s try to unpack how that happened.

From the very start, many digital games were multiplayer, optionally if not unavoidably so. Spacewar!, the program generally considered the first fully developed graphical videogame, was exclusively multiplayer from its inception in the early 1960s. Ditto Pong, the game that launched Atari a decade later, and with it a slow-building popular craze for electronic games, first in public arcades and later in living rooms. Multiplayer here was not so much down to design intention as technological affordances. Pong was an elaborate analog state machine rather than a full-blown digital computer, relying on decentralized resistors and potentiometers and the like to do its “thinking.” It was more than hard enough just to get a couple of paddles and a ball moving around on the screen of a gadget like this; a computerized opponent was a bridge too far.

Very quickly, however, programmable microprocessors entered the field, changing everyone’s cost-benefit analyses. Building dual controls into an arcade cabinet was expensive, and the end result tended to take up a lot of space. The designers of arcade classics like Asteroids and Galaxian soon realized that they could replace the complications of a human opponent with hordes of computer-controlled enemies, flying in rudimentary, partially randomized patterns. Bulky multiplayer machines thus became rarer and rarer in arcades, replaced by slimmer, more standardized single-player cabinets. After all, if you wanted to compete with your friends in such games, there was still a way to do so: you could each play a round against the computerized enemies and compare your scores afterward.

While all of this was taking shape, the Trinity of 1977 — the Radio Shack TRS-80, Apple II, and Commodore PET — had ushered in the personal-computing era. The games these early microcomputers played were sometimes ports or clones of popular arcade hits, but just as often they were more cerebral, conceptually ambitious affairs where reflexes didn’t play as big — or any — role: flight simulations, adventure games, war and other strategy games. The last were often designed to be played optimally or even exclusively against another human, largely for the same reason Pong had been made that way: artificial intelligence was a hard thing to implement under any circumstances on an 8-bit computer with as little as 16 K of memory, and it only got harder when you were asking said artificial intelligence to formulate a strategy for Operation Barbarossa rather than to move a tennis racket around in front of a bouncing ball. Many strategy-game designers in these early days saw multiplayer options almost as a necessary evil, a stopgap until the computer could fully replace the human player, thus alleviating that eternal problem of the war-gaming hobby on the tabletop: the difficulty of finding other people in one’s neighborhood who were able and willing to play such weighty, complex games.

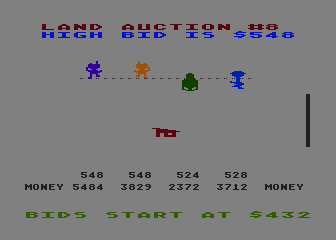

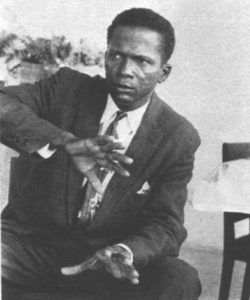

At least one designer, however, saw multiplayer as a positive advantage rather than a kludge — in fact, as the way the games of the future by all rights ought to be. “When I was a kid, the only times my family spent together that weren’t totally dysfunctional were when we were playing games,” remembered Dani Bunten Berry. From the beginning of her design career in 1979, when she made an auction game called Wheeler Dealers for the Apple II,[3]Wheeler Dealers and all of her other games that are mentioned in this article were credited to Dan Bunten, the name under which she lived until 1992. multiplayer was her priority. In fact, she was willing to go to extreme lengths to make it possible; in addition to a cassette tape containing the software, Wheeler Dealers shipped with a custom-made hardware add-on, the only method she could come up with to let four players bid at once. Such experiments culminated in M.U.L.E., one of the first four games ever published by Electronic Arts, a deeply, determinedly social game of economics and, yes, auctions for Atari and Commodore personal computers that many people, myself included, still consider her unimpeachable masterpiece.

And yet it was Seven Cities of Gold, her second game for Electronic Arts, that became a big hit. Ironically, it was also the first she had ever made with no multiplayer option whatsoever. She was learning to her chagrin that games meant to be played together on a single personal computer were a hard sell; such machines were typically found in offices and bedrooms, places where people went to isolate themselves, not in living rooms or other spaces where they went to be together. She decided to try another tack, thereby injecting the “online” part of POMG into our discussion.

In 1988, Electronic Arts published Berry’s Modem Wars, a game that seems almost eerily prescient in retrospect, anticipating the ludic zeitgeist of more than a decade later with remarkable accuracy. It was a strategy game played in real time (although not quite a real-time strategy of the resource-gathering and army-building stripe that would later be invented by Dune II and popularized by Warcraft and Command & Conquer). And it was intended to be played online against another human sitting at another computer, connected to yours by the gossamer thread of a peer-to-peer modem hookup over an ordinary telephone line. Like most of Berry’s games, it didn’t sell all that well, being a little too far out in front of the state of her nation’s telecommunications infrastructure.

Nevertheless, she continued to push her agenda of computer games as ways of being entertained together rather than alone over the years that followed. She never did achieve the breakout hit she craved, but she inspired countless other designers with her passion. She died far too young in 1998, just as the world was on the cusp of embracing her vision on a scale that even she could scarcely have imagined. “It is no exaggeration to characterize her as the world’s foremost authority on multiplayer computer games,” said Brian Moriarty when he presented Dani Bunten Berry with the first ever Game Developers Conference Lifetime Achievement Award two months before her death. “Nobody has worked harder to demonstrate how technology can be used to realize one of the noblest of human endeavors: bringing people together. Historians of electronic gaming will find in these eleven boxes [representing her eleven published games] the prototypes of the defining art form of the 21st century.” Let this article and the ones that will follow it, written well into said century, serve as partial proof of the truth of his words.

For by the time Moriarty spoke them, other designers had been following the trails she had blazed for quite some time, often with much more commercial success. A good early example is Populous, Peter Molyneux’s strategy game in real time (although, again, not quite a real-time strategy) that was for most of its development cycle strictly a peer-to-peer online multiplayer game, its offline single-player mode being added only during the last few months. An even better, slightly later one is DOOM, John Carmack and John Romero’s game of first-person 3D mayhem, whose star attraction, even more so than its sadistic single-player levels, was the “deathmatch” over a local-area network. Granted, these testosterone-fueled, relentlessly zero-sum contests weren’t quite the same as what Berry was envisioning for gaming’s multiplayer future near the end of her life; she wished passionately for games with a “people orientation,” directed toward “the more mainstream, casual players who are currently coming into the PC market.” Still, as the saying goes, you have to start somewhere.

But there is once more a caveat to state here about access, or rather the lack thereof. Being built for local networks only — i.e., networks that lived entirely within a single building or at most a small complex of them — DOOM deathmatches were out of reach on a day-to-day basis for those who didn’t happen to be students or employees at institutions with well-developed data-processing departments and permissive or oblivious authority figures. Outside of those ivory towers, this was the era of the “LAN party,” when groups of gamers would all lug their computers over to someone’s house, wire them together, and go at it over the course of a day or a weekend. These occasions went on to become treasured memories for many of their participants, but they achieved that status precisely because they were so sporadic and therefore special.

And yet DOOM‘s rise corresponded with the transformation of the Internet from an esoteric tool for the technological elite to the most flexible medium of communication ever placed at the disposal of the great unwashed, thanks to a little invention out of Switzerland called the World Wide Web. What if there was a way to move DOOM and other games like it from a local network onto this one, the mother of all wide-area networks? Instead of deathmatching only with your buddy in the next cubicle, you would be able to play against somebody on another continent if you liked. Now wouldn’t that be cool?

The problem was that local-area networks ran over a protocol known as IPX, while the Internet ran on a completely different one called TCP/IP. Whoever could bridge that gap in a reasonably reliable, user-friendly way stood to become a hero to gamers all over the world.

Jay Cotton discovered DOOM in the same way as many another data-processing professional: when it brought down his network. He was employed at the University of Georgia at the time, and was assigned to figure out why the university’s network kept buckling under unprecedented amounts of spurious traffic. He tracked the cause down to DOOM, the game that half the students on campus seemed to be playing more than half the time. More specifically, the problem was caused by a bug, which was patched out of existence by John Carmack as soon as he was informed. Problem solved. But Cotton stuck around to play, the warden seduced by the inmates of the asylum.

He was soon so much better at the game than anyone else on campus that he was getting a bit bored. Looking for worthier opponents, he stumbled across a program called TCPSetup, written by one Jake Page, which was designed to translate IPX packets into TCP/IP ones and vice versa on the fly, “tricking” DOOM into communicating across the vast Internet. It was cumbersome to use and extremely unreliable, but on a good day it would let you play DOOM over the Internet for brief periods of time at least, an amazing feat by any standard. Cotton would meet other players on an Internet chat channel dedicated to the game, they’d exchange IP addresses, and then they’d have at it — or try to, depending on the whims of the Technology Gods that day.

On August 22, 1994, Cotton received an email from a fellow out of the University of Illinois — yes, PLATO’s old home — whom he’d met and played in this way (and beaten, he was always careful to add). His name was Scott Coleman. “I have some ideas for hacking TCPSetup to make it a little easier. Care to do some testing later?” Coleman wrote. “I’ve already emailed Jake [Page] on this, but he hasn’t responded (might be on vacation or something). If he approves, I’m hoping some of these ideas might make it into the next release of TCPSetup. In the meantime, I want to do some experimenting to see what’s feasible.”

Jake Page never did respond to their queries, so Cotton and Coleman just kept beavering away on their own, eventually rewriting TCPSetup entirely to create iDOOM, a more reliable and far less fiddly implementation of the same concept, with support for three- or four-player deathmatches instead of just one-on-one duels. It took off like a rocket; the pair were bombarded with feature requests, most notably to make iDOOM work with other IPX-only games as well. In January of 1995, they added support for Heretic, one of the most popular of the first wave of so-called “DOOM clones.” They changed their program’s name to “iFrag” to reflect the fact that it was now about more than just DOOM.

Having come this far, Cotton and Coleman soon made the conceptual leap that would transform their software from a useful tool to a way of life for a time for many, many thousands of gamers. Why not add support for more games, they asked themselves, not in a bespoke way as they had been doing to date, but in a more sustainable one, by turning their program into a general-purpose IPX-to-TCP/IP bridge, suitable for use with the dozens of other multiplayer games out there that supported only local-area networks out of the box. And why not make their tool into a community while they were at it, by adding an integrated chat service? In addition to its other functions, the program could offer a list of “servers” hosting games, which you could join at the click of a button; no more trolling for opponents elsewhere on the Internet, then laboriously exchanging IP addresses and meeting times and hoping the other guy followed through. This would be instant-gratification online gaming. It would also provide a foretaste at least of persistent online multiplayer gaming; as people won matches, they would become known commodities in the community, setting up a meta-game, a sporting culture of heroes and zeroes where folks kept track of win-loss records and where everybody clamored to hear the results when two big wheels faced off against one another.

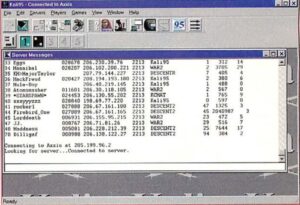

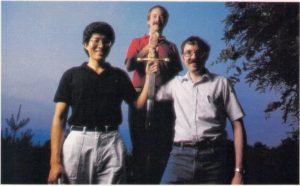

Cotton and Coleman renamed their software for the third time in less than nine months, calling it Kali, a name suggested by Coleman’s Indian-American girlfriend (later his wife). “The Kali avatar is usually depicted with swords in her hands and a necklace of skulls from those she has killed,” says Coleman, “which seemed appropriate for a deathmatch game.” Largely at the behest of Cotton, always the more commercially-minded of the pair, they decided to make Kali shareware, just like DOOM itself: multiplayer sessions would be limited to fifteen minutes at a time until you coughed up a $20 registration fee. Cotton went through the logistics of setting up and running a business in Georgia while Coleman did most of the coding in Illinois. (Rather astonishingly, Cotton and Coleman had still never met one another face to face in 2013, when gaming historian David L. Craddock conducted an interview with them that has been an invaluable source of quotes and information for this article.)

Kali certainly wasn’t the only solution in this space; a commercial service called DWANGO had existed since December of 1994, with the direct backing of John Carmack and John Romero, whose company id Software collected 20 percent of its revenue in return for the endorsement. But DWANGO ran over old-fashioned direct-dial-up connections rather than the Internet, meaning you had to pay long-distance charges to use it if you weren’t lucky enough to live close to one of its host computers. On top of that, it charged $9 for just five hours of access per month, with the fees escalating from there. Kali, by contrast, was available to you forever for as many hours per month as you liked after you plunked down your one-time fee of $20.

So, Kali was popular right from its first release on April 26, 1995. Yet it was still an awkward piece of software for the casual user despite the duo’s best efforts, being tied to MS-DOS, whose support for TCP/IP relied on a creaky edifice of third-party tools. The arrival of Windows 95 was a godsend for Kali, as it was for computer gaming in general, making the hobby accessible in a way it had never been before. The so-called “Kali95” was available by early 1996, and things exploded from there. Kali struck countless gamers with all the force of a revelation; who would have dreamed that it could be so easy to play against another human online? Lloyd Case, for example, wrote in Computer Gaming World magazine that using Kali for the first time was “one of the most profound gaming experiences I’ve had in a long time.” Reminiscing seventeen years later, David L. Craddock described how “using Kali for the first time was like magic. Jumping into a game and playing with other people. It blew my fourteen-year-old mind.” In late 1996, the number of registered Kali users ticked past 50,000, even as quite possibly just as many or more were playing with cracked versions that bypassed the simplistic serial-number-registration process. First-person-shooter deathmatches abounded, but you could also play real-time strategies like Command & Conquer and Warcraft, or even the Links golf simulation. Computer Gaming World gave Kali a special year-end award for “Online-Enabling Technology.”

Competitors were rushing in at a breakneck pace by this time, some of them far more conventionally “professional” than Kali, whose origin story was, as we’ve seen, as underground and organic as that of DOOM itself. The most prominent of the venture-capital-funded startups were MPlayer (co-founded by Brian Moriarty of Infocom and LucasArts fame, and employing Dani Bunten Berry as a consultant during the last months of her life) and the Total Entertainment Network, better known as simply TEN. In contrast to Kali’s one-time fee, they, like DWANGO before them, relied on subscription billing: $20 per month for MPlayer, $15 per month for TEN. Despite slick advertising and countless other advantages that Kali lacked, neither would ever come close to overtaking its scruffy older rival, which had price as well as oodles of grass-roots goodwill on its side. Jay Cotton:

It was always my belief that Kali would continue to be successful as long as I never got greedy. I wanted everyone to be so happy with their purchase that they would never hesitate to recommend it to a friend. [I would] never charge more than someone would be readily willing to pay. It also became a selling point that Kali only charged a one-time fee, with free upgrades forever. People really liked this, and it prevented newcomers (TEN, Heat [a service launched in 1997 by Sega of America], MPlayer, etc.) from being able to charge enough to pay for their expensive overheads.

Kali was able to compete with TEN, MPlayer, and Heat because it already had a large established user base (more users equals more fun) and because it was much, much cheaper. These new services wanted to charge a subscription fee, but didn’t provide enough added benefit to justify the added expense.

It was a heady rush indeed, although it would also prove a short-lived one; Kali’s competitors would all be out of business within a year or so of the turn of the millennium. Kali itself stuck around after that, but as a shadow of what it had been, strictly a place for old-timers to reminisce and play the old hits. “I keep it running just out of habit,” said Jay Cotton in 2013. “I make just enough money on website ads to pay for the server.” It still exists today, presumably as a result of the same force of habit.

One half of what Kali and its peers offered was all too obviously ephemeral from the start: as the Internet went mainstream, developers inevitably began building TCP/IP support right into their games, eliminating the need for an external IPX-to-TCP/IP bridge. (For example, Quake, id Software’s much-anticipated follow-up to DOOM, did just this when it finally arrived in 1996.) But the other half of what they offered was community, which may have seemed a more durable sort of benefit. As it happened, though, one clever studio did an end-run around them here as well.

The folks at Blizzard Entertainment, the small studio and publisher that was fast coming to rival id Software for the title of the hottest name in gaming, were enthusiastic supporters of Kali in the beginning, to the point of hand-tweaking Warcraft II, their mega-hit real-time strategy, to run optimally over the service. They were rewarded by seeing it surpass even DOOM to become the most popular game there of all. But as they were polishing their new action-CRPG Diablo for release in 1996, Mike O’Brien, a Blizzard programmer, suggested that they launch their own service that would do everything Kali did in terms of community, albeit for Blizzard’s games alone. And then he additionally suggested that they make it free, gambling that knowledge of its existence would sell enough games for them at retail to offset its maintenance costs. Blizzard’s unofficial motto had long been “Let’s be awesome,” reflecting their determination to sell exactly the games that real hardcore gamers were craving, honed to a perfect finish, and to always give them that little bit extra. What better way to be awesome than by letting their customers effortlessly play and socialize online, and to do so for free?

The idea was given an extra dollop of urgency by the fact that Westwood Games, the maker of Warcraft‘s chief competitor Command & Conquer, had introduced a service called Westwood Chat that could launch people directly into a licensed version of Monopoly. (Shades of Dani Bunten Berry’s cherished childhood memories…) At the moment it supported only Monopoly, a title that appealed to a very different demographic from the hardcore crowd who favored Blizzard’s games, but who knew how long that would last?[4]Westwood Chat would indeed evolve eventually into Westwood Online, with full support for Command & Conquer, but that would happen only after Blizzard had rolled out their own service.

So, when Diablo shipped in the last week of 1996, it included something called Battle.net, a one-click chat and matchmaking service and multiplayer facilitator. Battle.net made everything easier than it had ever been before. It would even automatically patch your copy of the game to the latest version when you logged on, pioneering the “software as a service” model in gaming that has become everyday life in our current age of Steam. “It was so natural,” says Blizzard executive Max Schaefer. “You didn’t think about the fact that you were playing with a dude in Korea and a guy in Israel. It’s really a remarkable thing when you think about it. How often are people casually matched up in different parts of the world?” The answer to that question, of course, was “not very often” in the context of 1997. Today, it’s as normal as computers themselves, thanks to groundbreaking initiatives like this one. Blizzard programmer Jeff Strain:

We believed that in order for it [Battle.net] to really be embraced and adopted, that accessibility had to be there. The real catch for Battle.net was that it was inside-out rather than outside-in. You jumped right into the game. You connected players from within the game experience. You did not alt-tab off into a Web browser to set up your games and have the Web browser try to pass off information or something like that. It was a service designed from Day One to be built into actual games.

The combination of Diablo and Battle.net brought a new, more palpable sort of persistence to online gaming. Players of DOOM or Warcraft II might become known as hotshots on services like Kali, but their reputation conferred no tangible benefit once they entered a game session. A DOOM deathmatch or a Warcraft II battle was a one-and-done event, which everyone started on an equal footing, which everyone would exit again within an hour or so, with nothing but memories and perhaps bragging rights to show for what had transpired.

Diablo, however, was different. Although less narratively and systemically ambitious than many of its recent brethren, it was nevertheless a CRPG, a genre all about building up a character over many gaming sessions. Multiplayer Diablo retained this aspect: the first time you went online, you had to pick one of the three pre-made first-level characters to play, but after that you could keep bringing the same character back to session after session, with all of the skills and loot she had already collected. Suddenly the link between the real people in the chat rooms and their avatars that lived in the game proper was much more concrete. Many found it incredibly compelling. People started to assume the roles of their characters even when they were just hanging out in the chat rooms, started in some very real sense to live the game.

But it wasn’t all sunshine and roses. Battle.net became a breeding ground of the toxic behaviors that have continued to dog online gaming to this day, a social laboratory demonstrating what happens when you take a bunch of hyper-competitive, rambunctious young men and give them carte blanche to have at it any way they wish with virtual swords and spells. The service was soon awash with “griefers,” players who would join others on their adventures, ostensibly as their allies in the dungeon, then literally stab them in the back when they least expected it, killing their characters and running off with all of their hard-won loot. The experience could be downright traumatizing for the victims, who had thought they were joining up with friendly strangers simply to have fun together in a cool new game. “Going online and getting killed was so scarring,” acknowledges David Brevick, Diablo‘s original creator. “Those players are still feeling a little bit apprehensive.”

To make matters worse, many of the griefers were also cheaters. Diablo had been born and bred a single-player game; multiplayer had been a very late addition. This had major ramifications. Diablo stored all the information about the character you played online on your local hard drive rather than the Battle.net server. Learn how to modify this file, and you could create a veritable god for yourself in about ten minutes, instead of the dozens of hours it would take playing the honest way. “Trainers” — programs that could automatically do the necessary hacking for you — spread like wildfire across the Internet. Other folks learned to hack the game’s executable files themselves. Most infamously, they figured out ways to attack other players while they were still in the game’s above-ground town, supposedly a safe space reserved for shopping and healing. Battle.net as a whole took on a siege mentality, as people who wanted to play honorably and honestly learned to lock the masses out with passwords that they exchanged only with trusted friends. This worked after a fashion, but it was also a betrayal of the core premise and advantage of Battle.net, the ability to find a quick pick-up game anytime you wanted one. Yet there was nothing Blizzard could do about it without rewriting the whole game from the ground up. They would eventually do this — but they would call the end result Diablo II. In the meanwhile, it was a case of player beware.

It’s important to understand that, for all that it resembled what would come later all too much from a sociological perspective, multiplayer Diablo was still no more persistent than Moria and Oubliette had been on the old PLATO network: each player’s character was retained from session to session, but nothing about the state of the world. Each world, or instance of the game, could contain a maximum of four human players, and disappeared as soon as the last player left it, leaving as its legacy only the experience points and items its inhabitants had collected from it while it existed. Players could and did kill the demon Diablo, the sole goal of the single-player game, one that usually required ten hours or more of questing to achieve, over and over again in the online version. In this sense, multiplayer Diablo was a completely different game from single-player Diablo, replacing the simple quest narrative of the latter with a social meta-game of character-building and player-versus-player combat.

For lots and lots of people, this was lots and lots of fun; Diablo was hugely popular despite all of the exploits it permitted — indeed, for some players perchance, because of them. It became one of the biggest computer games of the 1990s, bringing online gaming to the masses in a way that even Kali had never managed. Yet there was still a ways to go to reach total persistence, to bring a permanent virtual world to life. Next time, then, we’ll see how mainstream commercial games of the 1990s sought to achieve a degree of persistence that the first MUD could boast of already in 1979. These latest virtual worlds, however, would attempt to do so with all the bells and whistles and audiovisual niceties that a new generation of gamers raised on multimedia and 3D graphics demanded. An old dog in the CRPG space was about to learn a new trick, creating in the process a new gaming acronym that’s even more of a mouthful than POMG.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books Stay Awhile and Listen Volumes 1 and 2 by David L. Craddock, Masters of Doom by David Kushner, and The Friendly Orange Glow by Brian Dear; Retro Gamer 43, 90, and 103; Computer Gaming World of September 1996 and May 1997; Next Generation of March 1997. Online sources include “The Story of Battle.net” by Wes Fenlon at PC Gamer, Dan Griliopoulos’s collection of interviews about Command & Conquer, Brian Moriarty’s speech honoring Dani Bunten Berry from the 1998 Game Developers Conference, and Jay Cotton’s history of Kali on the DOOM II fan site. Plus some posts on The CRPG Addict, to which I’ve linked in the article proper.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The PLATO Moria was a completely different game from the 1983 single-player roguelike that bore the same name. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Not the same game as the 2002 Bioware CRPG of the same name. |

| ↑3 | Wheeler Dealers and all of her other games that are mentioned in this article were credited to Dan Bunten, the name under which she lived until 1992. |

| ↑4 | Westwood Chat would indeed evolve eventually into Westwood Online, with full support for Command & Conquer, but that would happen only after Blizzard had rolled out their own service. |