Judith Pintar was responsible for what popular consensus holds to be the two best games ever created using AGT. She wrote 1991’s Cosmoserve herself, then organized the team of authors that created 1992’s Shades of Gray. Both works are inextricably bound up with the online life of their era. Cosmoserve is a simulation and gentle satire of daily life on CompuServe, the most popular of the pre-World Wide Web commercial online services, while Shades of Gray was created by people who had met one another only on CompuServe, who used a CompuServe chat room as their primary means of communication. Given that I’ve written so voluminously on the text adventures of Infocom and others over the years, and given I’ve spent most of the last two months chronicling the net before the Web, a conversation with Judith about text adventures on CompuServe seemed the perfect way to tie the two strands together.

As it happened, though, I got much more than I’d bargained for. Although Cosmoserve and Shades of Gray were written many years ago now, Judith’s interest in interactive fiction has never abated. For years she’s been using it as a tool for pedagogical purposes in the classes she teaches, and she’s recently started some fascinating projects in the realm of what we might call massively-multiauthored interactive fiction. I hope you enjoy this transcript of our wide-ranging conversation on such subjects as the pros and cons of AGT, the life and times of the CompuServe Gamers Forum, the fostering of empathy through interactivity, and the plight of verbally-oriented computer programmers in a STEM-heavy world.

Thank you for agreeing to do this so close to Christmas! It’s a great gift for me and my readers.

I’m so delighted that you got in touch with me. I’ve been a fan of your historical work.

It made a huge difference to me when I realized you had released your extended review and treatment of Cosmoserve in your IF history. It was at a really low point in my academic life, and I found it, and thought, “Oh, my God! This is who I am!” It was very nice.

Anyway, I like your writing style and your approach to the history of IF a lot. I teach from your work.

Thank you!

I played Cosmoserve and Shades of Gray for the first time… oh, must be fifteen years ago now. I had a job working in IT on the graveyard shift. We had twelve-hour shifts, from 7 PM to 7 AM, and a lot of the time there just wasn’t that much to do. I couldn’t play a conventional computer game, but I could play IF games because it would just look like I was working at a terminal, typing commands. So I went through the back-history of AGT, a lot of the games nobody ever plays anymore.

And that’s when I played Cosmoserve and Shades of Gray, which I think were probably just about the two best things that were ever done with AGT. It was a very limited system in some ways, but you certainly bent it to your will.

I was always a big cheerleader for AGT. It is true that I went into the Pascal source code for both CosmoServe and Shades of Gray, but most of the changes I made were to increase the available resources in order to accommodate the size of these games. I believed at the time that people’s complaints about AGT were not reasonable, that you could do pretty much whatever you wanted with the language if you were creative and diligent. I still believe this. Until Inform 7 came along, AGT was my IF teaching language of choice.

But obviously the technology improved with TADS and Inform. They’re more flexible languages; AGT had a fair number of assumptions about the world and so on built into it. TADS and Inform of course had some as well, but they could be modified much more easily.

And I do think one other thing that came in with what we think of as the modern IF community, with Curses and the first IF competition and so on in 1993 and 1994, was a strong ethic of quality, of testing games and taking the work very seriously. From my standpoint, that’s something that’s missing in a lot of the AGT work. There was more of a tendency for people to just write games and put them out there without seeking out much feedback or focusing on adding that final polish. So, it wasn’t strictly a matter of technology. There was a cultural shift as well.

I’m not sure that’s completely fair. Some different rules maybe came in with the IF Competition that took over from the AGT Competition, and it certainly broadened the number of people who were involved, but I think the situation is more complex.

I think it’s more accurate to say that there were multiple IF worlds. In CompuServe Gamers Forum, people were writing games and sharing them and critiquing them. Even the contest format really had its origins in the AGT Contest. There was no Internet around, so depending on what bulletin board or users group you were a member of, you could run in different circles. The people who wrote AGT games weren’t necessarily in the same circles as those who formed the modern community, and when AGT fell away, it was really…

Well, in my case, for example, I was not very motivated to learn TADS, because I was publicly identified with AGT. I felt protective of it, and of David Malmberg and what he had achieved with AGT, and what his contest did for popularizing the writing of IF in those early days.

I know it looks like I disappeared from the IF world. I had been a presence in the early 1990s, I was being interviewed, I was very active on CompuServe Gamers Forum, etc., etc. And then I just seemed to be gone. I wasn’t actually. I just went to graduate school. I was still writing IF and teaching AGT at a point when David announced he would no longer be maintaining it. That left me without a language. I could program in Pascal, but I wasn’t really able to take it over. When CompuServe was bought by AOL, that left me without my community too, though I was still part of the larger IF world. I never stopped writing and teaching IF.

Well, the “IF community” has always been very fragmented. You have this sort of central community associated with the IF Comp, which is the most academically respected today. But you also have a whole community of people working in a language called ADRIFT, which is easier to use than Inform or TADS. It’s not really a programming-oriented but a database-based system, where you can put a game together using a GUI. Then for a long time there was an “adult” interactive-fiction community, who focused on textual pornography. I’m not really sure how active they still are.

Is it true that they continued to use AGT?

Yes, they stuck with AGT for a long, long time. To whatever extent AGT developed a bad reputation among the larger IF community, I think that may have contributed somewhat to it. Many of the AIF people were using AGT to churn out a lot of junk games meant only for the purpose of getting off. They stuck with AGT well past 2000. If they’re still around, I suspect many of them may still be using it.

My sense of AGT comes from the fact that I taught it to middle-school and high-school kids. I found it to be a really wonderful teaching language. Just a few years ago, I got an email from an old student who now runs a children’s game conference in Austin. He credits that to the fact that I taught him to write games in AGT in the early 1990s.

I actually ported Cosmoserve to Inform; that’s how I learned Inform 7. Going from AGT to Inform 7 was very interesting. There are things — and you must believe me here! — that AGT does better and makes easier than Inform 7, even though Inform 7 is clearly a wildly more powerful language.

It might be useful to look back here to the earliest days of home computers, when BASIC was around, with line numbers and single-letter variable names, GOTO statements everywhere — everything “real” programmers hate. So, people came along to tell all these computer owners that they should be using Pascal or some other more proper programming language. One famous computer scientist said that anyone who learned BASIC would be “mutilated beyond hope of regeneration.”

But during that era ordinary people were actually programming computers. They were writing games, writing little tools for their own use. That was part of the ethos of owning a computer. The old computer magazines were all very programming-oriented.

Today our programming languages are very well-engineered, excellent tools for professional programmers making heavy-duty applications, but we really do lack any modern equivalent to what BASIC used to be: something not so pretty, not so formally or theoretically correct, but that ordinary people can just pick up and make something with. Maybe in the context of IF it was AGT that was filling that role, to be replaced by slicker languages like TADS and Inform that lacked the same approachability.

I do have a story about AGT that you might like. Earlier I wrote about a game that officially won the 2nd AGT Contest — but it was the first real Contest. That was A Dudley Dilemma by Lane Barrow. I looked him up and interviewed him for the blog, as I’m interviewing you now. We talked quite a lot about his game’s design and what he would do differently if he made it today. He got inspired to pick up the old AGT tools and make some changes, changing a few things that by modern standards were a bit borderline on the fairness scale. That new version’s on the IF Archive now. He said he was shocked at how quickly he was able to pick up AGT again after not using it for 25 or maybe close to 30 years.

So, that’s a story you might appreciate. I never created anything with AGT, so I can’t speak to it that much.

But maybe we could go back and lay some groundwork about the person you were when you created Cosmoserve and Shades of Gray. I’m always amazed by the huge range of backgrounds and experiences that people working in IF have. The thing that leaps out first from your biography is that you were a Celtic harpist throughout the 1980s. That’s certainly an unusual career choice. Would you care to talk a bit about it?

Sure. I’ll tell you the skeleton story.

My BA from the University of Wisconsin was in folklore. It was a degree I put together myself because in my junior year I realized I had no major. So, I made an interdisciplinary major from courses I had already taken: Old Norse, Old English, Greek Mythology. This was the age of Joseph Campbell, and we were all sort of questing.

One summer I hitchhiked through Britain trying to find a harp-maker. My idea about this was intensely romantic, completely based on wanting to be a storyteller — a storyteller needed a harp. I ended up finding a harp-maker in Wales. I had to go back to get it six months later.

To my complete surprise, I was able to play this instrument. I took to it. I learned to play by composing. So I was really quickly performing original music in Milwaukee and around the Midwest.

On the strength of my folklore degree, I applied for a job in the Milwaukee Public School System as a storyteller, even though I had never told a story out loud. I got the job, which was terrifying. I thought I would go in front of a class with my harp and go “pling, pling” and tell little stories, but they walked me into a gym with 500 students waiting for me. I tanked so bad that first time.

Somehow I did become a professional storyteller. I played the harp and told stories in the folk-music circuit, at Renaissance fairs, at Celtic music festivals. I had also landed a recording contract with Sona Gaia, an imprint of the Narada new-age music label. My albums included liner notes with stories that had originally been performed live.

In 1987, I needed to make my third album, so I moved to Colorado, up in the mountains, with two wolf-hybrid dogs and my harp and a little pickup truck. I needed a computer, so for $1000 I bought a used PCs Limited XT clone, 8 MHz in “turbo” mode. On this computer was GAGS by Mark Welch, the precursor to AGT. It was shareware, so I sent a check to Mark Welch. He wrote back to tell me that GAGS was now AGT, and Dave Malmberg was maintaining it. So I purchased AGT.

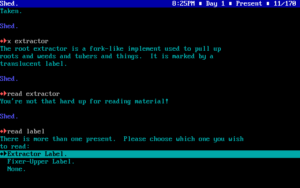

One fun thing in Cosmoserve is that GAGS is running there.

Yeah, there’s a little GAGS game in there. Is there some in-joke to that, associated with being in Wisconsin on a dairy farm? It was kind of a non sequitur for me as a player. I was thinking, okay, why am I here of all places?

That’s a joke on me! I’m from Milwaukee, I wrote that cow game.

That was your first game?

It was one of them. My first games were written in a cabin in the mountains of Colorado. How’s that for a romantic beginning?

Very nice!

When you first got this copy of GAGS, was that actually your first exposure to text adventures?

No, no, no. Infocom, man! Infocom!

Okay, so you were already a hardcore Infocom fan.

My mom was a high-school math teacher, and she in the 1970s was as tech-savvy as a math teacher could be. Our first personal computer was an Apple II. My first gaming experience was typing in little BASIC text adventures. So, going back to the late 1970s and early 1980s, I was already writing IF, as much as that was possible in BASIC. Then I started playing the Infocom games at home with family and friends. I think I may own them all. So, as an Infocom freak, it was very exciting to find GAGS. It was the first time I realize it would be possible to author a full-length game.

Do you have any favorites in the Infocom catalog that spring to mind?

Well, I loved Zork. How do you not love Zork? And what’s the one that has all the little robots?

That’s Suspended.

Okay. I would say that of all the Infocom games I was most influenced by Suspended.

Interesting. That’s in some ways the most unusual Infocom game. It’s more of a strategy game that’s played in text than a traditional text adventure. It was also, incidentally, the game that prompted Douglas Adams to decide he wanted to make The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy into an Infocom game. Now that you mention it, I fancy I can see some of it in Cosmoserve.

Absolutely. I wanted to shift or jar the player out of reading text and fool them into being present. I believe I succeeded because I got many emails from people telling me that when they played Cosmoserve they referred to it as “going online.” It felt to them like they were going online when they played. Of course, it looked identical to CompuServe. The logon screen was identical in what it said, and also in how long it took to load. There was some metalepsis because there were limits to how far I could make AGT imitate it. But I did pretty well in some places. When the virus infects your own computer and you do “chkdsk” in DOS, and it starts to show that you have all these files that are replicating at this incredible speed and things are starting to get corrupted, people would quit the game, terrified I had infected their computer.

So, backing up just for a moment, how did you end up on CompuServe in the first place?

I moved at the end of 1988 to Santa Cruz, California, with my husband-to-be. There I became an artist-in-residence and started to teach IF. And it was at that point or possibly earlier that I joined CompuServe Gamers Forum. That was huge for me; that was my IF community. More than an IF community. We talked all kinds of games.

It was very pleasant, very civil. There wasn’t a lot of trolling that I recall. Maybe partly because you were paying to be there. And it was really well-moderated. There was always a sysop present in the scheduled public chats.

My handle was Teela Brown. She’s a character in Larry Niven’s Ringworld; she’s the luckiest woman in the world. That’s how I felt in that era of my life. It’s still my handle now with the Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation.

I just have to say that I’m so excited about your work on CompuServe. I’m really so happy that you’ve written about CompuServe because I have a lot of sorrow about it as kind of a lost world. If Cosmoserve can help your project, that would be awesome.

Yeah. The problem is that in histories of these things the focus always goes to the early ARPANET, the invention of TCP/IP, etc. Which is important — incredibly important — but a huge part of contemporary online culture can’t actually be traced back to the ARPANET and early Internet. It was CompuServe that invented and/or popularized real-time chat, e-commerce, online travel reservations, online newspapers, online encyclopedias, much of online gaming, etc., etc. Few people seem to remember that. If you look at what you do on the Internet today, at least as much stems from the early commercial online services as from the early Internet. They should both be given their due.

One of the great tragedies for me as a historian is that all of this stuff that took place on CompuServe has apparently been lost forever. I can go back to look at Usenet discussions that took place 30 years ago; that stuff is still there. CompuServe unfortunately is a different story. That sad reality makes Cosmoserve hugely valuable as more than just an adventure game.

I actually just learned this year that CompuServe is a lost world, that there is no backup. It occurred to me then to be grateful that I had done this. I couldn’t now replicate the experience.

Yes. This to me is one of the fascinating things about text adventures. Unlike the vast majority of games, they’re very personal works, and they tend to be much more reflective of the lives of the people that made them. Of course, you have Cosmoserve, which shows what it was like to log onto this long-gone online service. But it goes even beyond that.

In the case of A Dudley Dilemma, Lane Barrow was a PhD student at Harvard, and he wrote a game about being a PhD student at Harvard. Son of Stagefright, which won the AGT Contest the year after A Dudley Dilemma, was written by a guy who was very active in community theater, so he set his game in the theater where he and his friends would put on plays. Or there’s a game called Save Princeton which was written by a young man who was a student at Princeton at the time, and he included all his friends in the game. That sort of thing is kind of frowned on in IF circles today because it’s not artistic or high-falutin’ enough, but at the same time, when I play that game now there’s actually something very poignant about it. I see all these bright kids who think they’ve got the world figured out, who are going to do this or do that after university. One of them has a Twin Peaks poster on his dorm-room wall; it’s a total time capsule. I wonder where these people are today. Maybe it resonates more with me than it might with others because I was about their age at about the same time. But I do think that that personal, time-capsule quality is kind of overlooked when people talk about IF.

Yes, I agree. I haven’t read anything addressing that. It’s very interesting.

So, how would you describe the discussions on CompuServe? Was there a lot of talk about how games should be made, what is good and bad design, what is fair and unfair?

Absolutely. We talked about everything, and we absolutely had conversations about what made a good game. There were people in Gamers Forum who wrote games as well as played games. It was really easy to get beta testers.

Those were the people who beta-tested Cosmoserve, which I submitted to the AGT Contest and won. The next year I didn’t want to submit another game; I thought that wasn’t fair. So I decided to organize Shades of Gray instead.

The CompuServe Gamers Forum was a real place to me. It had a geography. There were rooms where you could enter and talk to people, and there was a library. It might seem strange that I would simulate CompuServe through IF, which is traditionally so map-based. But for me CompuServe was mapped too. Gamers Forum had an entirely different feel from other Forums. You traveled between them. They all felt like different geographic destinations in a work of IF. But there were other people there too. You could go into a Forum conference room at any time, day or night, and somebody might be there.

So I recreated that in Cosmoserve. You can just go to a conference and see if anybody is there. Sometimes they are, and sometimes they aren’t. That part feels really real.

And it’s not a bug in Cosmoserve the way the number of people who are supposedly in the Forum always changes. It’s randomized in Cosmoserve as a joke because I never believed it was true on CompuServe.

In terms of the Gamers Forum members who were writing text adventures, were they all or mostly all working with AGT? TADS came out in 1990, but it wasn’t used anywhere near as much as AGT during the early 1990s.

I wouldn’t say we were an AGT community. People were experimenting with many game-making systems — not just IF but other sorts of games as well. We tried all of them, so there was a discussion about tools too, and comparisons. We were pretty eclectic. We didn’t have an identity like the newsgroups had, of being an IF community. We IF people were just in there, fairly integrated. There was no sense of shame, no sense that we were lesser than other kinds of games at all. It was just one of the kinds of games that were being played by everyone.

I assume you as well were playing other kinds of games — certainly by 1990 or so, with Infocom gone. Do you recall what other games you were playing?

Sure. We played all the Sierra Online games. We enjoyed them, despite people having an attitude about the writing, that the general quality of game writing had declined when games went graphic. But that didn’t stop us from playing them! We all loved Myst when it came out too, and there were barely any words there at all.

I was also a big NetHack addict. It’s one of my favorite games ever. I like to teach it.

Have you ever ascended?

I have!

Congratulations!

Thanks!

I talk about that game because it shows that a good game can evoke emotion using an ASCII character. You cry when your pet dies. Your heart beats hard when the wizard is chasing you, even though it’s just a little letter going across the screen. So I always talk about that game in game-design classes. The power is in the design. You can have gorgeous graphics and interesting mechanics, and it can still be emotionally empty and touch you not at all. NetHack for me is very powerful.

So, as you’re working on Cosmoserve, it’s obviously a huge technical challenge to bend AGT in that direction. You’ve hinted that you were fairly friendly with David Malmberg. Did he help at all with the changes you had to make for Cosmoserve?

No, no. I hacked it. I did have to tell him that I had done it because I was concerned that I was cheating, but he wasn’t bothered. You can’t compile my game files with the regular compiler.

It started out as just a straight-up game, but as it went on it got bigger and there were things I wanted to do, especially how things printed to the screen. Because I was concerned about cheating in the contest, I did less than I might have. The rumors of my hacking are exaggerated! You didn’t need to change the program to do great things with AGT.

One thing about Cosmoserve that’s interesting is that you published it in 1991, but it’s set in 2001. You’re extrapolating what’s going to happen to computer technology in the future. You assume, as anyone might, that Intel would continue with the “x86” nomenclature instead of coming out with the Pentium line, so you have this “786” computer in there. And then it’s funny that you’re still using DOS ten years on.

It’s true that whenever you set a story in the future you have to live with what you imagined. I did imagine that there would be GUIs, but that R.J. Wright himself would still want to use DOS. This is also a self-reference. I miss DOS tremendously. I never liked GUIs. I’m verbally-oriented, not visually-oriented, and I was imagining that I would never give up DOS. On my desktop right now, my garbage can is called “Unnecessary Metaphor.” I used to be able to delete a file by typing “delete,” but now I have to imagine that the file is a little piece of paper and I have to physically pick it up and drag it to a little picture of a garbage can to get rid of it. I hated that from the first time that I saw it.

I thought of R.J. Wright too as the kind of person who into the 21st century would still be using DOS. But I was also imagining that there would be VR.

Yes, that’s a huge contrast. DOS and VR!

Right, I imagined more and less. I imagined VR would be more immersive and multiplayer than it is now, and I imagined that DOS would make it.

And there’s another thing: I never imagined the fall of Borland. The “Orfland” products that the player uses in Cosmoserve, and the quest to get Orfland customer service to provide a patch, are an affectionate send-up of Borland products — Turbo Pascal, Paradox, etc. — and the Borland Forum on CompuServe. When we lived in Santa Cruz my husband did some contract programming for Borland, so we were also in their corporate social circle.

A funny story from that era: while I was writing Cosmoserve, which was really a full time job for months and months, cash was tight. So I tried office temping, though I had no prior work experience. All I wrote on my application at the temp agency under skills, as I recall, was “Can Type Real Fast.” I got one job — I was sent to Borland CEO Philippe Kahn’s office, to type all the info from his personal Rolodex into his very large, state of the art mobile phone. Now, this Rolodex was jaw-dropping. It had in it the personal addresses and home phone numbers of pretty much every important personage in computing: Gates, Jobs, Wozniak, everybody. It took two days to finish the job because as soon as Philippe found out I was a musician we spent a lot of time hanging out and talking. I had heard his band, the Turbo Jazz Band, play at a big Borland employee gathering — he plays sax and flute. So we compared our experiences of composing and improvising and performing and recording and by the time I was finished, we were like friends, just fellow musicians, and we gifted each other with our latest CDs. I remember him as a charismatic man at the top of his game. I was going to write him into a sequel to Cosmoserve, but then Borland fell, and of course I never wrote that sequel. I did name my cat Philippe though.

One aspect of Cosmoserve which a modern player might not be too excited about is the time element. It’s a game which you really have to play several times. When I played it, I had to make a schedule for myself. First I’d go on these reconnaissance missions to see what was going on where and when. Then I could use my schedule to make a winning run. As I’m sure you know, there are a lot of modern players who absolutely hate that approach.

That actually got fixed in the 1997 release. I went to the IF Archive and asked them to switch out the old Cosmoserve version for the new version. And they said no, they wouldn’t delete it, because it didn’t belong to me anymore; it belonged to the public, but they’d be happy to add the new version. That was the moment I realized that there was a history of IF bigger than any individual game or designer. Now, being on the IFTF board, I love that caretaking our shared history is part of my job.

The new Inform 7 version of Cosmoserve is much more pleasant to play. I instituted a more comprehensive hint system in every part of the game so that the player can move through the game more smoothly.

I must not have played the 1997 version because I remember this fairly intense time pressure. But I’m an old-school player; I played the Infocom mysteries that were also constructed like this. So, if I know a game is constructed that way going in, it’s not a deal-breaker for me.

Just as a design question, how did you approach removing the time pressure?

I just started the story earlier in the day. The player now has nearly 24 hours to get their Pascal program ready for the courier coming to pick it up the next morning. That seems to be enough time, though I will be looking for additional beta-testing feedback on that. I also removed the much-hated “you must eat pizza or you will die” mechanic. If someone really misses these old-style pressure puzzles they can still play the original version. But the Inform 7 version is more pleasant for the modern player.

Then I also added a hint system using Aunt Edna. Did the version you played have Aunt Edna?

I think I remember her coming by and complaining that I’ll never get a girlfriend or a boyfriend if I keep living like this.

In the new Inform 7 version, you can send her away if you don’t want her. But she’s basically giving you hints to get you through the first phase in your house, to get you online faster. Without breaking the mood, she’ll give you hints to get that first part solved.

And then I’m in the game as Teela Brown. I always was, in VR, but I really improved that so that the game is tracking what you’ve done and not done. Instead of a big laundry list of things you can ask me, which breaks the mood, if you ask me for a hint I’ll tell you, “You need to do this by this time of night” or “This happened at 7:00 and you missed it,” so you don’t go all the way to the end of the game and realize, oh, my, God, I needed to have done this thing. That’s horrible; everybody hates that.

So, let’s talk about Shades of Gray just a little. Which part of that was yours?

The Tarot card reader.

Okay. She’s kind of the jumping-off point to all of the different vignettes.

Yes. I wrote the code that links them all. I also took the individual pieces and made them narratively coherent.

Shades of Gray was unusual for its era in that there’s an overt message to the game; it’s trying to say something. Infocom had done a little bit of that with A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity, but their options were always limited by being a commercial game company, by not wanting to offend anybody. Steve Meretzky at Infocom had a lot of ideas for other very political games, and his managers always said, no, you can’t do that.

Of course, later on in the IF community there would be a lot of people making very self-consciously “literary” games. But that was a little later than the AGT era. Do you recall how you decided you wanted to make a game that would not just be another adventure game, that would leave the player with a message?

We didn’t start with that. I started with a message asking who wanted to make a game for the next Competition. And a bunch of people said yes, they did. The team I wound up putting together included Mark Baker, Steve Bauman, Belisana, Hercules, Mike Laskey, and Cindy Yans in addition to myself.

There were a lot of logistics just getting to the nitty-gritty of game design. We didn’t have any clear idea what the game would be. And of course, trying to drive a carriage with twelve horses is really, really difficult. Everybody wanted to do their own thing.

We let people do that for a while while we continued to discuss themes, but pretty soon we came to the idea of moral ambiguity. Robin Hood is a scoundrel from the Sheriff’s point of view, for example. We wanted to show that life and politics are nuanced.

Belisana came up with the overarching narrative, and she wrote the ending.

Was she responsible for the Haiti historical material?

Yes.

For an American in 1992, that’s a little bit of an esoteric choice of subject. Did she have some connection to Haiti? Do you know where that came from?

I don’t. She came up with the idea and we all loved it. Without giving away any spoilers here, it is fair to say that this is a story about American history, as much as it is about Haiti. And she executed it brilliantly, in her vignette, and in the game ending.

Yes, that was definitely the most powerful part of the game for me.

The making of Shades of Gray was a CompuServe story, a pretty profound one, about what the service made possible, collaboratively. We didn’t know anything about each other personally. We were fellow forum members who became a team.

It was expensive to go on CompuServe; you had to pay per minute. So you rationed the amount of time you spent online. You wrote all your messages offline, then logged on to send them. In order to do Shades of Gray on CompuServe, I had to convince the Gamers Forum to give us the “free flag.”

And this meant you got to be online for free?

Yes. Anybody involved with the project would get a free flag while they were working on this game. Not only did we get this free flag, but we got a room of our own. I never met any of the other people who worked on the game. That’s really normal now, in the age of the Internet, but at that time it was really strange.

We talked and talked and talked about what Shades of Gray would be; everybody had their own ideas. We had this general theme of moral ambiguity. Everybody wrote their code separately, then I had the job of taking it all and merging it, which was insanely difficult. And we won the AGT Competition. They had to make a special “group project” category for us, to be fair to the shorter games.

Creating Shades of Gray was really fun, and I’d say that the game was more influential on my career path in IF than Cosmoserve was. It’s the inspiration for what I do now at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where my students engage in massive, ongoing collaborative IF.

Wow!

I’ve just finished my third year teaching Inform 7 in an IF programming and design course at the U of I. Besides working on their own games, students collaborate on a game that is set on our campus — that is, if our campus had toilet stalls collapsing into underground tunnels with zombies gnawing on the bones of graduate students. Called The Quad Game, it’s an IF sandbox with hundreds of locations and fifty or so endings — so far. It is rough in patches and extravagantly incomplete, deliberately so.

On the first day of class I let the students play the game in groups, each group setting out in a different direction from the center of the campus. I ask them to write down everything that happens that is annoying or buggy or incomplete. I really encourage them to complain. Then I tell them to write at the top of the paper, “To Do.” By the end of the semester they will have to fix it all.

More ambitiously, I’m in the process of developing a public history/collaborative programming project called The Illinois Map. I usually explain it as something like Wikipedia-meets-Minecraft. The vision is to get the entire state of Illinois to become programming literate, by learning the Inform 7 language in order to write interactive, immersive games that simulate key moments in Illinois history.

The site will be like Wikipedia in that every project submitted will need to be referenced. Someone who wants to write a simulation on Abraham Lincoln’s career as a lawyer, for example, will have to provide historical background with primary sources and a justification for why their simulation is historically significant, using secondary sources. They also have to come up with a compelling little story, and then write the Inform 7 code to carry it out.

I’ve taught another IF class for the last two years in which students submit an Illinois Map proposal as their final project– I’ve got fifty of these ready to go as soon as the site is ready. They’re at various stages of narrative development and coding sophistication, but that’s the point. Like Wikipedia, multiple people will be able to collaborate on revising and improving the various parts of any project page.

I imagine that a High School Social Studies teacher will send their students to the Illinois Map. A student will search to see if anybody has done anything on their hometown, and lo and behold: there’s already a little game somebody has started. Maybe the research is good, but the story is lame and the code is pretty weak. They can give some feedback, suggest some edits, or offer code corrections. If their project veers too much, they can submit a new one.

They will gain status as they contribute to the Map, and will aspire to become proficient enough to take the best projects and incorporate them into a Master Game that will let players explore Illinois history from one end to the other, from its prehistoric beginnings to its imagined future.

And do you hope to release this publicly at some point?

The Quad Game is already available to the public. I’ve got some grant-writing to do before the Illinois Map goes live.

Then the other thing I’m working on is to teach Inform 7 inside an Inform 7 game. I want to write a game where the object is to write code, and where the code the player is writing changes the game they’re playing. You can see my first pass at that. What you get at the end is code which you can cut and paste and drop into Inform to play it.

A couple of people have done something similar to that. A game called Informatory some years ago taught not Inform 7 but Inform 6. And then Andrew Plotkin, whom I’m sure you know, made a game called Lists and Lists to teach a dialect of LISP.

That was actually one of my first languages! I learned LISP, then Pascal, then C++.

I have found Inform 7 to be an ideal first programming language. It introduces the concepts students need to pass a Python class: objects, inheritance, recursion, variables, loops, lists, tables, but it teaches them through story. I don’t know of a Python course that doesn’t make you learn these concept through algebra. But Inform 7 teaches data relationships and ontologies through metaphor, which everyone’s brain is wired to understand. Pedagogically I call this approach “narrative-based computational thinking.”

This approach is also academically practical. We have an informatics minor here for which students must complete a CS class. These students come from any number of programs across campus — business, arts, journalism — and some of them have a hard time passing a CS course. We had the idea that students taking my Inform 7 class would be able to get through a Python class afterwards, no problem. I think that’s true, but I don’t have the research — yet! We’re going to try to demonstrate it.

I would like to make Inform 7 as ubiquitous as PowerPoint. I think it could be a breakthrough in widespread programming literacy.

So, I think you and I agree with each other philosophically. Our sense of the significance of IF, of where it belongs in the world.

I’m a very strange case. I got my first computer when I was quite young. I grew up with computers, have always loved them. At the same time, though, in everything apart from computers I’m a very verbally-oriented person. When I’d take standardized tests, I’d always score fifteen or twenty points higher on the verbal versus the math component.

In a way, I think I’ve always seen programming a little bit differently. When I write code, my algorithms aren’t necessarily that wonderful, but I load up the code with commentary. So, the Inform 7 natural-language approach feels very natural to me. In a sense, I was already describing what I was doing in natural language, then having to translate it down to C or whatever. With Inform 7, I don’t have to take the second step.

I know you’re very busy with these massively collaborative IF projects, but have you ever thought about doing another game on your own or as part of a smaller team?

I never stopped writing games. I just didn’t release them publicly. I had won the two competitions I entered, so I was done with competitions, but competitions were how games were still being released. So for a decade or more, I mostly shared my games with my students, as tutorials, sort of like Emily Short’s games in the Inform 7 Cookbook.

But now I do have an Inform 7 game of my own in beta. I wrote it just because it was fun, and for the technical challenge. It’s an IF poker game. You’re Alice, and you’re falling down the well as you play poker with the white rabbit. You’re going down as the rabbit is going up. The cards are scattered randomly through the well. He picks up cards and you pick up cards, and the game keeps track of your hands. But the cards are alive; they fight with each other. So, there’s a story, but you can only access it by having certain cards together in your hand. On the one hand you’re trying to win the poker game, but on the other you can’t really win unless you have in your hand the right characters who will reveal information to you to get the backstory. This was so much fun to write.

Then I have another massive project…

Instead of publishing my sociology dissertation as an academic book, I wrote a novel based on my field experiences in Croatia in the late 1990s. I spent much of that time in Dubrovnik, where Game of Thrones and Star Wars both have filmed. The story tells the 1500-year history of Dubrovnik as a series of failed love affairs. I never found an agent to represent this opus — no one liked the asynchronous relationship between the contemporary story and the vignettes. It finally occurred to me that the real problem was that I had written a novel with the narrative sensibility of an IF. It needs to be read in a non-linear way.

So, now I want to turn it into an actual IF. I’m thinking of making it a multi-platform work where I would use Twine for some aspects of the game along with some parser-based elements. Maybe I can weigh in on the battle between choice-based and parser-based IF by embracing them both. And it also fulfills my other idea, which is IF as historical simulation. I’m interested in broadening IF beyond both games and literature. All of that is packed into the project, which unfortunately I can’t afford to take the time to do. I will eventually get to it.

That’s a very interesting direction which is under-explored. If you look at IF’s intrinsic qualities, probably the thing it does best of all — certainly the thing it does most easily — is setting. It can be an incredibly powerful tool for putting you in a place, whether it’s a fantastical place or an historical place. That’s actually something that comes more naturally to the form than narrative or plot, although ever since Infocom there’s been this huge focus on “waking up inside a story,” as they liked to put it.

Certainly IF as history hasn’t been done all that much. Trinity did it of course, and there’s a game called 1893: A World’s Fair Mystery that did it very well, but most IF tends to veer off toward science fiction or fantasy.

Yes. That’s what I’m investigating pedagogically: how to use IF in history classes, in social-science classes. An example of a student project from a class taught on American minority groups:

In Illinois in the early 1990s we had a controversy over a Native American burial mound which had become a museum called Dixon Mounds in Lewiston, Illinois. They had open graves; they’d been open since the 1930s, when an amateur anthropologist found this place and put up a museum around it. In the 1990s Native Americans started protesting Dixon Mounds. It was a really tangled couple of years between people who supported the museum and people coming into town to protest; one governor got involved, then another, etc.

So, my students studied this last year. Then they were divided up into six groups and they wrote an IF simulation of the same physical place from six different points in history: at the point when the people who made the burial mounds lived, then later when another Native group lived in the area, then when the bones were found, then when the museum was active, then the protests, and finally the present, when a new museum has covered the bones. The idea is to explore this geographic space through time, using real sources to make responsive NPCs. So a player going into the games could find out about the controversy by talking to people and experiencing it.

It’s not fun. A lot of the students in their reflections at the end of the semester said, “I wish you’d just let us write games.” To them I said, “Well, take my other class!” But the question on the table is whether a game can create empathy. Can we write a simulation that will cause players not to “have fun” — although it would be nice if they could enjoy themselves — and not even just to learn what happened, but to see another perspective.

I think you’re right that IF’s potential for this sort of thing has been under-explored. I really need to play Trinity again. I think I could use it to show my students what’s possible at the high end.

You know, games are or can be so good at fostering empathy. When you read a book or watch a movie, you’re always at a certain remove. But when you play a game, that’s you in the game.

And if you can put a player in the role of somebody else and say, “Okay, walk a mile in these shoes,” maybe you can do some good. What about a game that places you in the role of a Palestinian dealing with the situation in Jerusalem? Somebody who supports the recently announced move of the American embassy to Jerusalem, who believes the Israelis are entirely right and the Palestinians entirely wrong… well, we kind of come back to what your team did in Shades of Gray, right? Maybe if you put that player in the role of somebody from the other side, you can actually foster some empathy, make the player realize that there are two sides to this story.

Yes. I mentioned that I did role-playing with my students before they started to write code. It was based on an approach to classroom role-playing called “Reacting to the Past.” It’s a new thing in history education. You have these really complicated games which sometimes take a whole semester to play. The students immerse themselves in a character, become that character. They read historical documents and learn to act as that character. Some of these games are fairly brutal. You might be a slave owner and have to make speeches arguing for slavery. It can be difficult for students to do this, but it gets inside history in a way that’s incredibly powerful.

In reviews of that approach, there are stories like what you’re describing, where somebody takes the role of somebody politically opposite to their own point of view. It’s not that they change their mind, but that they come away with a more nuanced view of the opposition — they understand where the others are coming from.

I’m trying to see whether I can use some of these techniques in computer games. Can I get students writing scenarios, writing characters, that will provide the same thing for players?

Last year a student wrote a game for The Illinois Map where you start out in a Holocaust museum. You’re just looking at objects in the museum, learning a little bit of history. Then you open a closet door and find yourself on the streets of Skokie, Illinois. There’s a big protest going on. You start to chat with people, and realize these are Holocaust survivors and others protesting the fact that the KKK wants to have a rally here. Of course, you’re on their side because you’ve just come out of the Holocaust museum. But then a guy from the ACLU is there, and starts to talk to you about free speech.

And that’s the whole scenario. It just takes you and drops you into that morally ambiguous moment. And that’s the end of the game. These are the kinds of things I’m encouraging my students to write — not huge games, just moments.

Some students are working on a simulation of the Springfield race riots of 1908. You start as a little African-American girl hiding in the attic of her house, peeking out the window watching the riot approach. Then you shift to being a white teenager on the ground, with the riot going past you. Your father is there, going to the riot. As the player, you can go or not go. Just the power of that juxtaposition is really effective.

What if our way of teaching history incorporated interactivity and immersion? I can’t say I’m succeeding. I’m just trying. I can’t suggest it to anybody else until I myself try it.

You’ve been involved with an amazing range of pursuits over your life. In addition to the things we’ve talked about today, you’ve worked as a sociologist, studied trauma in Croatia, written a history of hypnotism. Why so many eclectic choices?

I would say that the thing that connects my entire career is narrative and the power of storytelling — collective storytelling, collective memory, collaborative storytelling. I have an academic interest in that, and I have a creative interest as well. Let’s Tell a Story Together… the name of your IF history. There’s something fairly profound in that. It’s why IF really is different from other types of games and other types of literature.

I think that may be a good note to leave on. Thank you again for doing this!

Thank you! This has been so much fun!

The feeling is mutual. This has been great. Take care, Judith.

Do remember to check out Judith’s personal projects and her fascinating classroom experiments, both now and in the future. I know that I for one will be watching with interest to see how her work evolves.