At the end of the 1990s, the two most popular genres in computer gaming were the first-person shooter and the real-time strategy game. They were so dominant that most of the industry’s executives seemed to want to publish little else. And yet at the beginning of the decade neither genre even existed.

The stories of how the two rose to such heady heights are a fascinating study in contrasts, of how influences in media can either go off like an explosion in a TNT factory or like the slow burn of a long fuse. Sometimes something appears and everyone knows instantly that it’s just changed everything; when the Beatles dropped Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967, there was no doubt that the proverbial goalposts in rock music had just been shifted. Other times, though, influence can take years to make itself felt, as was the case for another album of 1967, The Velvet Underground & Nico, about which Brian Eno would later famously say that it “only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band.”

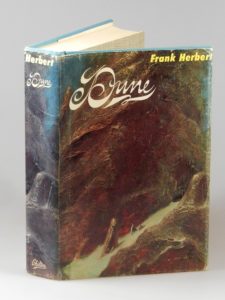

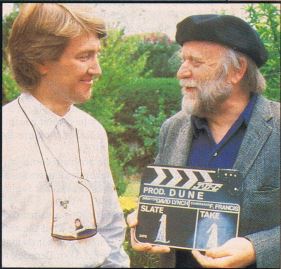

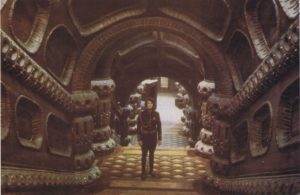

Games are the same. Gaming’s Sgt. Pepper was DOOM, which came roaring up out of the shareware underground at the tail end of 1993 to sweep everything from its path, blowing away all of the industry’s extant conventional wisdom about what games would become and what role they would play in the broader culture. Gaming’s Velvet Underground, on the other hand, was the avatar of real-time strategy, which came to the world in the deceptive guise of a sequel in the fall of 1992. Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty sported its Roman numeral because its transnational publisher had gotten its transatlantic cables crossed and accidentally wound up with two separate games based on Frank Herbert’s epic 1965 science-fiction novel — one made in Paris, the other in Las Vegas. The former turned out to be a surprisingly evocative and playable fusion of adventure and strategy game, but it was the latter that would quietly — oh, so quietly in the beginning! — shift the tectonic plates of gaming.

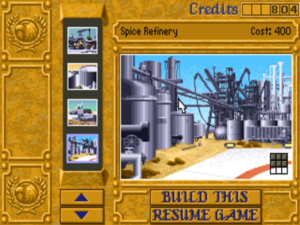

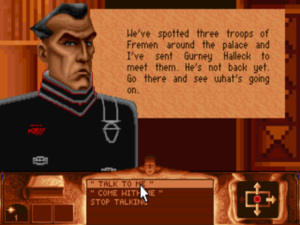

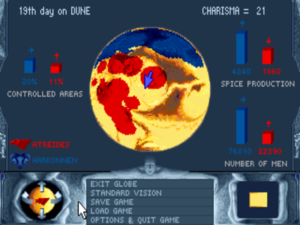

For Dune II, which was developed by Westwood Studios and published by Virgin Games, really was the first recognizable implementation of the genre of real-time strategy as we have come to know it since. You chose one of three warring trading houses to play, then moved through a campaign made up of a series of set-piece scenarios, in which your first goal was always to make yourself an army by gathering resources and using them to build structures that could churn out soldiers, tanks, aircraft, and missiles, all of which you controlled by issuing them fairly high-level orders: “go here,” “harvest there,” “defend this building,” “attack that enemy unit.” Once you thought you were strong enough, you could launch your full-on assault on the enemy — or, if you weren’t quick enough, you might find yourself trying to fend off his attack. What made it so different from most of the strategy games of yore was right there in the name: in the fact that it all played out in real time, at a pace that ranged from the brisk to the frantic, making it a test of your rapid-fire mousemanship and your ability to think on your feet. Bits and pieces of all this had been seen before — perhaps most notably in Peter Molyneux and Bullfrog’s Populous and the Sega Genesis game Herzog Zwei — but Dune II was where it all came together to create a gaming paradigm for the ages.

That said, Dune II was very much a diamond in the rough, a game whose groundbreaking aspirations frequently ran up against the brick wall of its limitations. It’s likely to leave anyone who has ever played almost any other real-time-strategy game seething with frustration. It runs at a resolution of just 320 X 200, giving only the tiniest window into the battlefield; it only lets you select and control one unit at a time, making coordinated attacks and defenses hard to pull off; its scenarios are somewhat rote exercises, differing mainly in the number of enemy hordes they throw against you as you advance through the campaign rather than the nature of the terrain or your objectives. Even its fog of war is wonky: the whole battlefield is blank blackness until one of your units gets within visual range, after which you can see everything that goes on there forevermore, whether any of your units can still lay eyes on it or not. And it has no support whatsoever for the multiplayer free-for-alls that are for many or most players the biggest draw of the genre.

Certainly Virgin had no inkling that they had a nascent ludic revolution on their hands. They released Dune II with more of a disinterested shrug than a fulsome fanfare, having expended most of their promotional energies on the other Dune, which had come out just a few months earlier. It’s a testimony to the novelty of the gameplay experience that it did as well as it did. It didn’t become a massive hit, but it sold well enough to earn its budget back and then some on the strength of reasonably positive reviews — although, again, no reviewer had the slightest notion that he was witnessing the birth of what would be one of the two hottest genres in gaming six years in the future. Even Westwood seemed initially to regard Dune II as a one-and-done. They wouldn’t release another game in the genre they had just invented for almost three years.

But the gaming equivalent of all those budding bedroom musicians who listened to that Velvet Underground record was also out there in the case of Dune II. One hungry, up-and-coming studio in particular decided there was much more to be done with the approach it had pioneered. And then Westwood themselves belatedly jumped back into the fray. Thanks to the snowball that these two studios got rolling in earnest during the mid-1990s, the field of real-time strategy would be well and truly saturated by the end of the decade, the yin to DOOM‘s yang. This, then, is the tale of those first few years of these two studios’ competitive dialog, over the course of which they turned the real-time strategy genre from a promising archetype into one of gaming’s two biggest, slickest crowd pleasers.

Blizzard Studios is one of the most successful in the history of gaming, so much so that it now lends its name to the Activision Blizzard conglomerate, with annual revenues in the range of $7.5 billion. In 1993, however, it was Westwood, flying high off the hit dungeon crawlers Eye of the Beholder and Lands of Lore, that was by far the more recognizable name. In fact, Blizzard wasn’t even known yet as Blizzard.

The company had been founded in late 1990 by Allen Adham and Mike Morhaime, a couple of kids fresh out of university, on the back of a $15,000 loan from Morhaime’s grandmother. They called their venture Silicon & Synapse, setting it up in a hole-in-the-wall office in Costa Mesa, California. They kept the lights on initially by porting existing games from one platform to another for publishers like Interplay — the same way, as it happened, that Westwood had gotten off the ground almost a decade before. And just as had happened for Westwood, Silicon & Synapse gradually won opportunities to make their own games once they had proven themselves by porting those of others. First there was a little auto-racing game for the Super Nintendo called RPM Racing, then a pseudo-sequel to it called Rock ‘n’ Roll Racing, and then a puzzle platformer called The Lost Vikings, which appeared for the Sega Genesis, MS-DOS, and the Commodore Amiga in addition to the Super Nintendo. None of these titles took the world by storm, but they taught Silicon & Synapse what it took to create refined, playable, mass-market videogames from scratch. All three of those adjectives have continued to define the studio’s output for the past 30 years.

It was now mid-1993; Silicon & Synapse had been in business for more than two and a half years already. Adham and Morhaime wanted to do something different — something bigger, something that would be suitable for computers only rather than the less capable consoles, a real event game that would get their studio’s name out there alongside the Westwoods of the world. And here there emerged another of their company’s future trademarks: rather than invent something new from whole or even partial cloth, they decided to start with something that already existed, but make it better than ever before, polishing it until it gleamed. The source material they chose was none other than Westwood’s Dune II, now relegated to the bargain bins of last year’s releases, but a perennial after-hours favorite at the Silicon & Synapse offices. They all agreed as to the feature they most missed in Dune II: a way to play it against other people, like you could its ancestor Populous. The bane of most multiplayer strategy games was their turn-based nature, which left you waiting around half the time while your buddy was playing. Real-time strategy wouldn’t have this problem of downtime.

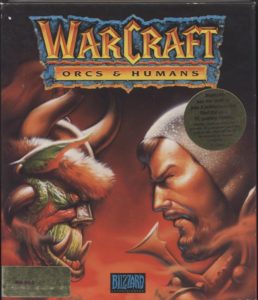

That became the design brief for Warcraft: Orcs & Humans: remake Dune II but make it even better, and then add a multiplayer feature. And then, of course, actually try to sell the thing in all the ways Virgin had not really tried to sell its inspiration.

To say that Warcraft was heavily influenced by Dune II hardly captures the reality. Most of the units and buildings to hand have a direct correspondent in Westwood’s game. Even the menu of icons on the side of the screen is a virtual carbon copy — or at least a mirror image. “I defensively joked that, while Warcraft was certainly inspired by Dune II, [our] game was radically different,” laughs Patrick Wyatt, the lead programmer and producer on the project. “Our radar mini-map was in the upper left corner of the screen, whereas theirs was in the bottom right corner.”

In the same spirit of change, Silicon & Synapse replaced the desert planet of Arrakis with a fantasy milieu pitting, as the subtitle would suggest, orcs against humans. The setting and the overall look of Warcraft owe almost as much to the tabletop miniatures game Warhammer as the gameplay does to Dune II; a Warhammer license was seriously considered, but ultimately rejected as too costly and potentially too restrictive. Years later, Wyatt’s father would give him a set of Warhammer miniatures he’d noticed in a shop: “I found these cool toys and they reminded me a lot of your game. You might want to have your legal department contact them because I think they’re ripping you off.”

Suffice to say, then, that Warcraft was even more derivative than most computer games. The saving grace was the same that it would ever be for this studio: that they executed their mishmash of influences so well. The squishy, squint-eyed art is stylized like a cartoon, a wise choice given that the game is still limited to a resolution of just 320 X 200, so that photo-realism is simply not on the cards. The overall look of Warcraft has more in common with contemporary console games than the dark, gritty aesthetic that was becoming so popular on computers. The guttural exclamations of the orcs and the exaggerated Monty Python and the Holy Grail-esque accents of the humans, all courtesy of regular studio staffers rather than outside voice actors, become a chorus line as you order them hither and yon, making Dune II seem rather stodgy and dull by comparison. “We felt too many games took themselves too seriously,” says Patrick Wyatt. “We just wanted to entertain people.”

Slavishly indebted though it is to Dune II in all the broad strokes, Warcraft doesn’t neglect to improve on its inspiration in those nitty-gritty details that can make the difference between satisfaction and frustration for the player. It lets you select up to four units and give them orders at the same time by simply dragging a box around them, a quality-of-life addition whose importance is difficult to overstate, one so fundamental that no real-time-strategy game from this point forward would dare not to include it. Many more keyboard shortcuts are added, a less technically impressive addition but one no less vital to the cause of playability when the action starts to heat up. There are now two resources you need to harvest, lumber and gold, in places of Dune II‘s all-purpose spice. Units are now a little more intelligent about interpreting your orders, such that they no longer blithely ignore targets of opportunity, or let themselves get mauled to death without counterattacking just because you haven’t explicitly told them to. Scenario design is another area of marked improvement: whereas every Dune II scenario is basically the same drill, just with ever more formidable enemies to defeat, Warcraft‘s are more varied and arise more logically out of the story of the campaign, including a couple of special scenarios with no building or gathering at all, where you must return a runaway princess to the fold (as the orcs) or rescue a stranded explorer (as the humans).

The orc on the right who’s stroking his “sword” looks so very, very wrong — and this screenshot doesn’t even show the animation…

And, as the cherry on top, there was multiplayer support. Patrick Wyatt finished his first, experimental implementation of it in June of 1994, then rounded up a colleague in the next cubicle over so that they could became the first two people ever to play a full-fledged real-time-strategy game online. “As we started the game, I felt a greater sense of excitement than I’d ever known playing any other game,” he says.

It was just this magic moment, because it was so invigorating to play against a human and know that it wasn’t some stupid AI. It was a player who was smart and doing his absolute best to crush you. I knew we were making a game that would be fun, but at that moment I knew the game would absolutely kick ass.

While work continued on Warcraft, the company behind it was going through a whirlwind of changes. Recognizing at long last that “Silicon & Synapse” was actually a pretty terrible name, Adham and Morhaime changed it to Chaos Studios, which admittedly wasn’t all that much better, in December of 1993. Two months later, they got an offer they couldn’t refuse: Davidson & Associates, a well-capitalized publisher of educational software that was looking to break into the gaming market, offered to buy the freshly christened Chaos for the princely sum of $6.75 million. It was a massive over-payment for what was in all truth a middling studio at best, such that Adham and Morhaime felt they had no choice but to accept, especially after Davidson vowed to give them complete creative freedom. Three months after the acquisition, the founders decided they simply had to find a decent name for their studio before releasing Warcraft, their hoped-for ticket to the big leagues. Adham picked up a dictionary and started leafing through it. He hit pay dirt when his eyes flitted over the word “blizzard.” “It’s a cool name! Get it?” he asked excitedly. And that was that.

So, Warcraft hit stores in time for the Christmas of 1994, with the name of “Blizzard Entertainment” on the box as both its developer and its publisher — the wheels of the latter role being greased by the distributional muscle of Davidson & Associates. It was not immediately heralded as a game that would change everything, any more than Dune II had been; real-time strategy continued to be more of a slowly growing snowball than the ton of bricks to the side of the head that the first-person shooter had been. Computer Gaming World magazine gave Warcraft a cautious four stars out of five, saying that “if you enjoy frantic real-time games and if you don’t mind a linear structure in your strategic challenges, Warcraft is a good buy.” At the same time, the extent of the game’s debt to Dune II was hardly lost on the reviewer: “It’s a good thing for Blizzard that there’s no precedent for ‘look and feel’ lawsuits in computer entertainment.”[1]This statement was actually not correct; makers of standup arcade games of the classic era and the makers of Tetris had successfully cowed the cloning competition in the courts.

Warcraft would eventually sell 400,000 units, bettering Dune II‘s numbers by a factor of four or more. As soon as it became clear that it was doing reasonably well, Blizzard started on a sequel.

Out of everyone who looked at Warcraft, no one did so with more interest — or with more consternation at its close kinship with Dune II — than the folks at Westwood. “When I played Warcraft, the similarities between it and Dune II were pretty… blatant, so I didn’t know what to think,” says the Westwood designer Adam Isgreen. Patrick Wyatt of Blizzard got the impression that his counterparts “weren’t exactly happy” at the slavish copying when they met up at trade shows, though he “reckoned they should have been pleased that we’d taken their game as a base for ours.” Only gradually did it become clear why Warcraft‘s existence was a matter of such concern for Westwood: because they themselves had finally decided to make another game in the style of Dune II.

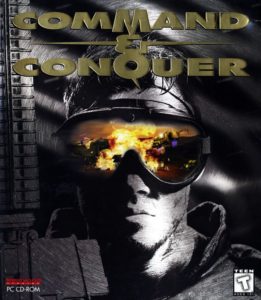

The game that Westwood was making could easily have wound up looking even more like the one that Blizzard had just released. The original plan was to call it Command & Conquer: Fortress of Stone and to set it in a fantasy world. (Westwood had been calling their real-time-strategy engine “Command & Conquer” since the days of promoting Dune II.) “It was going to have goldmines and wood for building things. Sound familiar?” chuckles Westwood’s co-founder Louis Castle. “There were going to be two factions, humans and faerie folk… pretty fricking close to orcs versus humans.”

Some months into development, however, Westwood decided to change directions, to return to a science-fictional setting closer to that of Dune II. For they wanted their game to be a hit, and it seemed to them that fantasy wasn’t the best guarantee of such a thing: CRPGs were in the doldrums, and the most recent big strategy release with a fantasy theme, MicroProse’s cult-classic-to-be Master of Magic, hadn’t done all that well either. Foreboding near-future stories, however, were all the rage; witness the stellar sales of X-COM, another MicroProse strategy game of 1994. “We felt that if we were going to make something that was massive,” says Castle, “it had to be something that anybody and everybody could relate to. Everybody understands a tank; everybody understands a guy with a machine gun. I don’t have to explain to them what this spell is.” Westwood concluded that they had made the right decision as soon as they began making the switch in software: “Tanks and vehicles just felt better.” The game lost its subtitle to become simply Command & Conquer.

While the folks at Blizzard were plundering Warhammer for their units and buildings, those at Westwood were trolling the Jane’s catalogs of current military hardware and Soldier of Fortune magazine. “We assumed that anything that was talked about as possibly coming was already here,” says Castle, “and that was what inspired the units.” The analogue of Dune II‘s spice — the resource around which everything else revolved — became an awesomely powerful space-born element come to earth known as tiberium.

Westwood included most of the shortcuts and conveniences that Blizzard had built into Warcraft, but went one or two steps further more often than not. For example, they also made it possible to select multiple units by dragging a box around them, but in their game there was no limit to the number of units that could be selected in this way. The keyboard shortcuts they added not only let you quickly issue commands to units and buildings, but also jump around the map instantly to custom viewpoints you could define. And up to four players rather than just two could now play together at once over a local network or the Internet, for some true mayhem. Then, too, scenario design was not only more varied than in Dune II but was even more so than in Warcraft, with a number of “guerilla” missions in the campaigns that involved no resource gathering or construction. It’s difficult to say to what extent these were cases of parallel innovation and to what extent they were deliberate attempts to one-up what Warcraft had done. It was probably a bit of both, given that Warcraft was released a good nine months before Command & Conquer, giving Westwood plenty of time to study it.

But other innovations in Command & Conquer were without any precedent. The onscreen menus could now be toggled on and off, for instance, a brilliant stroke that gave you a better view of the battlefield when you really needed it. Likewise, Westwood differentiated the factions in the game in a way that had never been done before. Whereas the different houses in Dune II and the orcs and humans in Warcraft corresponded almost unit for unit, the factions in Command & Conquer reflected sharply opposing military philosophies, demanding markedly different styles of play: the establishment Global Defense Initiative had slow, strong, and expensive units, encouraging a methodical approach to building up and husbanding your forces, while the terroristic Brotherhood of Nod had weaker but faster and cheaper minions better suited to madcap kamikaze rushes than carefully orchestrated combined-arms operations.

Yet the most immediately obvious difference between Command & Conquer and Warcraft was all the stuff around the game. Warcraft had been made on a relatively small budget with floppy disks in mind. It sported only a brief opening cinematic, after which scenario briefings consisted of nothing but scrolling text and a single voice over a static image. Command & Conquer, by contrast, was made for CD-ROM from the outset, by a studio with deeper pockets that had invested a great deal of time and energy into both 3D animation and full-motion video, that trendy art of incorporating real-world actors and imagery into games. The much more developed story line of Command & Conquer is forwarded by little between-mission movies that, if not likely to make Steven Spielberg nervous, are quite well-done for what they are, featuring as they do mostly professional performers — such as a local Las Vegas weatherman playing a television-news anchorman — who were shot by a real film crew in Westwood’s custom-built blue-screen studio. Westwood’s secret weapon here was Joseph Kucan, a veteran theater director and actor who oversaw the film shoots and personally played the charismatic Nod leader Kane so well that he became the very face of Command & Conquer in the eyes of most gamers, arguably the most memorable actual character ever associated with a genre better known for its hordes of generic little automatons. Louis Castle reckons that at least half of Command & Conquer‘s considerable budget went into the cut scenes.

The game was released with high hopes in August of 1995. Computer Gaming World gave it a pretty good review, four stars out of five: “The entertainment factor is high enough and the action fast enough to please all but the most jaded wargamers.”

The gaming public would take to it even more than that review might imply. But in the meantime…

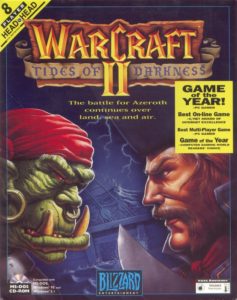

As I noted in an earlier article, numbered sequels weren’t really commonplace for strategy games prior to the mid-1990s. Blizzard had originally imagined Warcraft as a strategy franchise of a different stripe: each game bearing the name would take the same real-time approach into a completely different milieu, as SSI was doing at the time with their “5-Star General” series of turn-based strategy games that had begun with Panzer General and continued with the likes of Fantasy General and Star General. But Blizzard soon decided to make their sequel a straight continuation of the first game, an approach to which real-time strategy lent itself much more naturally than more traditional styles of strategy game; the set-piece story of a campaign could, after all, always be continued using all the ways that Hollywood had long since discovered for keeping a good thing going. The only snafu was that either the orcs or the humans could presumably have won the war in the first game, depending on which side the player chose. No matter: Blizzard decided the sequel would be more interesting if the orcs had been the victors and ran with that.

Which isn’t to say that building upon its predecessor’s deathless fiction was ever the real point of Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness. Blizzard knew now that they had a competitor in Westwood, and were in any case eager to add to the sequel all of the features and ideas that time had not allowed them to include in the first game. There would be waterways and boats to sail on them, along with oil, a third resource, one that could only be mined at sea. Both sides would get new units to play with, while elves, dwarves, trolls, ogres, and goblins would join the fray as allies of one of the two main racial factions. The interface would be tweaked with another welcome shortcut: selecting a unit and right-clicking somewhere would cause it to carry out the most logical action there without having to waste time choosing from a menu. (After all, if you selected a worker unit and sent him to a goldmine, you almost certainly wanted him to start collecting gold. Why should you have to tell the game the obvious in some more convoluted fashion?)

But perhaps the most vital improvement was in the fog of war. The simplistic implementations of same seen in the first Warcraft and Command & Conquer were inherited from Dune II: areas of the map that had been seen once by any of your units were revealed permanently, even if said units went away or were destroyed. Blizzard now made it so that you would see only a back-dated snapshot of areas currently out of your units’ line of sight, reflecting what was there the last time one of your units had eyes on them. This innovation, no mean feat of programming on the part of Patrick Wyatt, brought a whole new strategic layer to the game. Reconnaissance suddenly became something you had to think about all the time, not just once.

Other improvements were not so conceptually groundbreaking, but no less essential for keeping ahead of the Joneses (or rather the Westwoods). For example, Blizzard raised the screen-resolution stakes, from 320 X 200 to 640 X 480, even as they raised the number of people who could play together online from Command & Conquer‘s four to eight. And, while there was still a limit on the number of units you could select at one time using Blizzard’s engine, that limit at least got raised from the first Warcraft‘s four to nine.

The story and its presentation, however, didn’t get much more elaborate than last time out. While Westwood was hedging its bets by keeping one foot in the “interactive movie” space of games like Wing Commander III, Blizzard was happy to “just” make Warcraft a game. The two series were coming to evince very distinct personalities and philosophies, just as gamers were sorting themselves into opposing groups of fans — with a large overlap of less partisan souls in between them, of course.

Released in December of 1995, Warcraft II managed to shake Computer Gaming World free of some of its last reservations about the burgeoning genre of real-time strategy, garnering four and a half stars out of five: “If you enjoy fantasy gaming, then this is a sure bet for you.” It joined Command & Conquer near the top of the bestseller lists, becoming the game that well and truly made Blizzard a name to be reckoned with, a peer in every sense with Westwood.

Meanwhile, and despite the sometimes bitter rivalry between the two studios and their fans, Command & Conquer and Warcraft II together made real-time strategy into a commercial juggernaut. Both games became sensations, with no need to shirk from comparison to even DOOM in terms of their sales and impact on the culture of gaming. Each eventually sold more than 3 million copies, numbers that even the established Westwood, much less the upstart Blizzard, had never dreamed of reaching before, enough to enshrine both games among the dozen or so most popular computer games of the entire 1990s. More than three years after real-time strategy’s first trial run in Dune II, the genre had arrived for good and all. Both Westwood and Blizzard rushed to get expansion packs of additional scenarios for their latest entries in the genre to market, even as dozens of other developers dropped whatever else they were doing in order to make real-time-strategy games of their own. Within a couple of years, store shelves would be positively buckling under the weight of their creations — some good, some bad, some more imaginative, some less so, but all rendered just a bit anonymous by the sheer scale of the deluge. And yet even the most also-ran of the also-rans sold surprisingly well, which explained why they just kept right on coming. Not until well into the new millennium would the tide begin to slacken.

With Command & Conquer and Warcraft II, Westwood and Blizzard had arrived at an implementation of real-time strategy that even the modern player can probably get on with. Yet there is one more game that I just have to mention here because it’s so loaded with a quality that the genre is known for even less than its characters: that of humor. Command & Conquer: Red Alert is as hilarious as it is unexpected, the only game of this style that’s ever made me laugh out loud.

Red Alert was first envisioned as a scenario pack that would move the action of its parent game to World War II. But two things happened as work progressed on it: Westwood decided it was different enough from the first game that it really ought to stand alone, and, as designer Adam Isgreen says, “we found straight-up history really boring for a game.” What they gave us instead of straight-up history is bat-guano insane, even by the standards of videogame fictions.

We’re in World War II, but in a parallel timeline, because Albert Einstein — why him? I have no idea! — chose to travel back in time on the day of the Trinity test of the atomic bomb and kill Adolf Hitler. Unfortunately, all that’s accomplished is to make world conquest easier for Joseph Stalin. Now Einstein is trying to save the democratic world order by building ever more powerful gadgets for its military. Meanwhile the Soviet Union is experimenting with the more fantastical ideas of Nikola Tesla, which in this timeline actually work. So, the battles just keep getting crazier and crazier as the game wears on, with teleporters sending units jumping instantly from one end of the map to the other, Tesla coils zapping them with lightning, and a fetching commando named Tanya taking out entire cities all by herself when she isn’t chewing the scenery in the cut scenes. Those actually display even better production values than the ones in the first game, but the script has become pure, unadulterated camp worthy of Mel Brooks, complete with a Stalin who ought to be up there singing and dancing alongside Der Führer in Springtime for Hitler. Even our old friend Kane shows up for a cameo. It’s one of the most excessive spectacles of stupidity I’ve ever seen in a game… and one of the funniest.

Joseph Stalin gets rough with an underling. When you don’t have the Darth Vader force grip, you have to do things the old-fashioned way…

Up there at the top is the killer commando Tanya, who struts across the battlefield with no regard for proportion.

Released in the dying days of 1996, Red Alert didn’t add that much that was new to the real-time-strategy template, technically speaking; in some areas such as fog of war, it still lagged behind the year-old Warcraft II. Nonetheless, it exudes so much joy that it’s by far my favorite of the games I’ve written about today. If you ask me, it would have been a better gaming world had the makers of at least a few of the po-faced real-time-strategy games that followed looked here for inspiration. Why not? Red Alert too sold in the multiple millions.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(Sources: the book Stay Awhile and Listen, Book I by David L. Craddock; Computer Gaming World of January 1995, March 1995, December 1995, March 1996, June 1996, September 1996, December 1996, March 1997, June 1997, and July 1997; Retro Gamer 48, 111, 128, and 148; The One of January 1993; the short film included with the Command & Conquer: The First Decade game collection. Online sources include Patrick Wyatt’s recollections at his blog Code of Honor, Dan Griliopoulos’s collection of interviews with Westwood alumni at Funambulism, Soren Johnson’s interview with Louis Castle for his Designer’s Notes podcast, and Richard Moss’s real-time-strategy retrospective for Ars Technica.

Warcraft: Orcs & Humans and Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness, are available as digital purchases at GOG.com. The first Command & Conquer and Red Alert are available in remastered versions as a bundle from Steam.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | This statement was actually not correct; makers of standup arcade games of the classic era and the makers of Tetris had successfully cowed the cloning competition in the courts. |

|---|