THE IMPLEMENTOR’S CREED

I create fictional worlds. I create experiences.

I am exploring a new medium for telling stories.

My readers should become immersed in the story and forget where they are. They should forget about the keyboard and the screen, forget everything but the experience. My goal is to make the computer invisible.

I want as many people as possible to share these experiences. I want a broad range of fictional worlds, and a broad range of “reading levels.” I can categorize our past works and discover where the range needs filling in. I should also seek to expand the categories to reach every popular taste.

In each of my works, I share a vision with the reader. Only I know exactly what the vision is, so only I can make the final decisions about content and style. But I must seriously consider comments and suggestions from any source, in the hope that they will make the sharing better.

I know what an artist means by saying, “I hope I can finish this work before I ruin it.” Each work-in-progress reaches a point of diminishing returns, where any change is as likely to make it worse as to make it better. My goal is to nurture each work to that point. And to make my best estimate of when it will reach that point.

I can’t create quality work by myself. I rely on other implementors to help me both with technical wizardry and with overcoming the limitations of the medium. I rely on testers to tell me both how to communicate my vision better and where the rough edges of the work need polishing. I rely on marketeers and salespeople to help me share my vision with more readers. I rely on others to handle administrative details so I can concentrate on the vision.

None of my goals is easy. But all are worth hard work. Let no one doubt my dedication to my art.

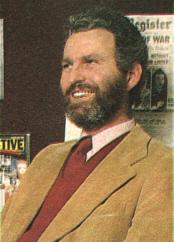

Stu Galley wrote the words you see above in early September of 1985, a time when Infocom was reeling through layoff after torturous layoff and looked very likely to be out of business in a matter of months. It served as a powerful affirmation of what Infocom really stood for, just as the misplaced dreams of Al Vezza and his Business Products people — grandiose in their own way but also so much more depressingly conventional — threatened to halt the dream of a new interactive literature in its tracks. “The Implementor’s Creed” is one of the most remarkable — certainly the most idealistic — texts to come out of Infocom. It’s also vintage Stu Galley, the Imp who couldn’t care less about Zork but burned with passion for the idea of interactive fiction actually worthy of its name.

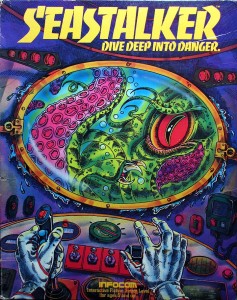

Galley’s passion and its associated perfectionism could sometimes make his life very difficult. In the final analysis perhaps a better critic of interactive fiction than a writer of it — his advice was frequently sought and always highly valued by all of the other Imps for their own projects — he would be plagued throughout his years at Infocom by self-doubt and an inability to come up with the sorts of original plots and puzzles that seemed to positively ooze from the likes of Steve Meretzky. Galley’s first completed game, The Witness, was developed from an outline provided by Marc Blank and Dave Lebling, while for his second, Seastalker, he collaborated with the prolific (if usually uncredited) children’s author Jim Lawrence. After finishing Seastalker, he had the idea to write a Cold War espionage thriller, tentatively called Checkpoint: “You, an innocent train traveler in a foreign country, get mixed up with spies and have to be as clever as they to survive.” He struggled for six months with Checkpoint, almost as long as it took some Imps to create a complete game, before voluntarily shelving it: “The problem there was that the storyline wasn’t sufficiently well developed to make it really interesting. I guess I had a vision of a certain kind of atmosphere in the writing that was rather hard to bring off.” Suffering from writer’s block as he was, it seemed a very good idea to everyone to pair him up again with Lawrence late in 1985.

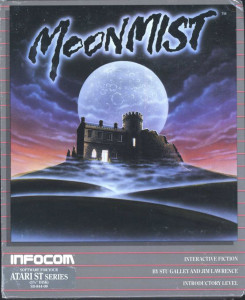

Just as Seastalker had been a Tom Swift, Jr., story with the serial numbers not-so-subtly filed away, the new game, eventually to be called Moonmist, would be crafted in the image of an even more popular children’s book protagonist with whom Lawrence had heaps of experience: none other than the original girl detective, Nancy Drew. She was actually fresher in Lawrence’s mind than Tom: he had spent much of his time during the first half of the 1980s anonymously churning out at least seven Nancy Drew novels for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, creators and owners of both the Tom and Nancy lines. As in Seastalker, you provide Moonmist with a name and gender when the game begins. The game and its accompanying feelies, however, would really kind of prefer it if you could see your way to playing as a female. Preferably as a female named “Nancy Drew,” if it’s all the same to you.

The plot is classic Nancy, a mystery set in a romantic old house, with a hint of the supernatural for spice. You’ve received a letter from your friend Tamara, for whom a semester abroad in Britain has turned into an engagement to a Cornish lord. It seems she has need for a girl detective. She’s living with her Lord Jack now at his Tresyllian Castle — chastely, in her own bedroom, of course — and all is not well. Lord Jack’s uncle, Lionel, was a globetrotting adventurer who recently died of “some sort of fatal jungle disease” that he may or may not have accidentally contracted. Lord Jack’s last girlfriend, the beautiful Deirdre, became entangled with his best friend Ian as well, and then allegedly committed suicide by drowning herself in the castle’s well after Jack broke it off with her in retaliation. Now her ghost is frequently seen haunting the castle and, Tamara claims, trying to kill her with venomous spiders and snakes. Joining you, Lord Jack, Tamara, and Ian at the castle for a memorial dinner marking the first anniversary of Lord Lionel’s death are Vivien, a painter and sculptor and the local bohemian; Iris, a Mayfair debutante who may or may not have something going with Ian; Dr. Wendish, Lord Lionel’s old best mate; and a slick antique dealer named Montague Hyde who’s eager to buy up the castle’s contents and sell them to the highest bidder.

Labelled as an “Introductory” level game, Moonmist splits the difference between earlier Infocom games to bear its “Mystery” genre tag. It doesn’t use the innovative player-driven plot chronology of the most recent of those, Ballyhoo, opting like Deadline, The Witness, and Suspect for a more simulationist turn-by-turn clock that gives you just a single night to solve the mystery. However, you the player don’t have to engage in the complicated, perfectly timed story interventions demanded by those earlier mysteries. After the events of the dinner party that sets the plot in motion, Moonmist is actually quite static, leaving you to your own devices to search the castle for clues and assemble a case that will reveal exactly what happened to Deirdre and who is dressing up as her ghost every night. (You didn’t think the ghost was real, did you? If so, you haven’t had much exposure to Nancy Drew or the works she spawned — like, for instance, Scooby-Doo.) You’ll also need to find a mysterious treasure brought back to Cornwall by Lord Lionel after one of his expeditions abroad. Depending on which version of Moonmist‘s mystery you’re playing, therein may also lie another nefarious plot.

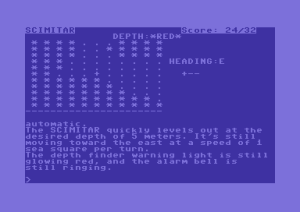

But wait… which version? Yes. We’ve come to the most interesting innovation in Moonmist. The identity of the guilty one(s) and the nature of the treasure change in four variations of the plot, which you choose between in-character by telling the butler your “favorite color” at the beginning of the game: green, blue, red, or yellow. (I’ve listed them in general order of complexity and difficulty, and thus in the order you might want to try them if you play Moonmist for yourself.) Infocom had tried a branching plotline once before, in Cutthroats, but not handled it terribly well. There the plot suddenly branched randomly well over halfway through the game, leading you the intrepid diver to explore one of two completely different sunken shipwrecks. If the objective was to make an Infocom game last longer, the Cutthroats approach was nonsensical; it just resulted in two unusually short experiences that added up to a standard Infocom game, not a full-length experience that could somehow be experienced afresh multiple times. And randomly choosing the story branch was just annoying, forcing the player to figure out when the branch was about to happen, save, and then keep reloading until the story went in the direction she hadn’t yet seen. The worst-case scenario would have to be the player who never even realized that the branch was happening at all, who was just left thinking she’d paid a lot of money for a really short adventure game.

While it’s not without problems of its own, Moonmist‘s approach makes a lot more sense. I do wish you were allowed to name your color a bit later; this would save you from having to play through a long sequence of identical introductions and preparations for the dinner party that kicks off the mystery in earnest. Still, Moonmist‘s decision to reuse the same stage set, as it were — rooms, objects, and characters — in the service of four different plots is a clever one, especially in light of the limitations of the 128 K Z-Machine. It’s of course an approach to ludic mystery that already had a long history by the time of Moonmist, beginning with the board game Cluedo back in 1949 and including in the realm of computer games the randomized mysteries of Electronic Arts’s not-quite-successful Murder on the Zinderneuf and the hand-crafted plots of Accolade’s stellar Killed Until Dead amongst others.

Moonmist is, alas, less successful at crafting 4 mysteries out of the same cast and stage than Killed Until Dead is at making 21. Moonmist‘s variations simply aren’t varied enough. Although the perpetrator, the treasure, and the incriminating evidence change, the process of finding them and assembling a case is the same from variation to variation. After you’ve solved one of the cases, and thus know the steps you need to follow, solving the others is fairly trivial. The process of finding Lord Lionel’s treasure is literally a scavenger hunt, a matter of following a trail of not-terribly-challenging clues in the form of written messages until you arrive at its conclusion. The guilty guest, meanwhile, is readily identifiable as the one person who leaves the dinner party and starts poking restlessly around the rest of the castle. And once the treasure is secured and the guilty one identified it’s mostly just a matter of searching that person’s room carefully to come up with the incriminating evidence you need and making an “arrest.” The changes from variation to variation amount to no more than a handful of objects placed in different rooms or swapped out and replaced with others, along with a bare few paragraphs of altered text. Although they’re not randomly generated, the cases feel unsatisfying enough that they almost just as well could have been; there’s a distinct “Colonel Mustard in the lounge with the candlestick” feel about the whole experience. Even the exact words that the guilty party says to you never change from variation to variation. Most damningly, Moonmist never even begins to succeed in giving you the feeling that you’re actually solving a mystery — the feeling that was so key to the appeal of Infocom’s original trilogy of mystery games. You’re just jumping through the hoops that will satisfy the game and cause it to spit out the full story in the form of the few bland sentences that follow your unmasking of the mastermind.

Some of these shortcomings can doubtless be laid at the feet of the aging 128 K Z-Machine, whose limitations were beginning to bite hard into Infocom’s own expectations of even a modest work like Moonmist by 1986. Even reusing most of the environment apparently didn’t give Galley and Lawrence enough room to craft four mysteries that truly felt unique. On the contrary, they were forced to save space by off-loading many of the room descriptions into a tourist’s guide to Tresyllian Castle included with the documentation. So-called “paragraph books” fleshing out stories (and providing copy protection) via text that couldn’t be packed into the game proper would soon become a staple of CRPGs of the latter half of the decade wishing to be a bit more ambitious in their storytelling than simple hack-and-slashers like Wizardry and The Bard’s Tale. But a CRPG is a very different sort of experience from a text adventure, and what’s tolerable or even kind of fun in the former doesn’t work at all in the latter. Having to constantly flip through a slick tourist brochure for room descriptions in Moonmist absolutely kills the atmosphere of a setting that should have fairly dripped with it. Tresyllian Castle is, after all, set on a spooky moor lifted straight out of The Hound of the Baskervilles, and comes complete with everything an American tourist thinks a British castle should, including a hedge maze (thankfully not implemented as an in-game maze), a dungeon, and a network of secret passages.

The text’s scarcity is doubly disappointing because the writing, when it’s there, is… well, I’m not sure I’d label it “great” or even “good,” but it is perfectly evocative of the sort of formulaically comforting children’s literature Jim Lawrence had so much experience crafting. How you react to it may very well depend on your own childhood experiences with Nancy Drew — or, perhaps more likely if you’re male like me, with her Stratemeyer Syndicate stablemates The Hardy Boys (yet another line for which Lawrence, inevitably, wrote a number of books). Just the idea of a white-haired old man raised in the swing era trying to write from the perspective of a 1980s teenager is weird; Nancy, born a teenager in 1930, is like Barbie and Bart Simpson eternally stuck at the same age both physically and mentally. Given that Nancy is, like Barbie, largely an aspirational fantasy for those who read her, Lawrence tries to make her life everything he thinks a contemporary twelve-year-old girl — the sweet spot of the Nancy Drew demographic — wishes her life could be in a few years. And given the artificial nature of the whole concept and its means of production, Nancy, and therefore Moonmist, inhabit a sort of cartoon reality where people routinely behave in ways that we never, ever see them behaving in real life. See, for example, your first meeting with Ian and Iris, nonsensically dancing together to pass the time before dinner “to the faint sound of rock music from a portable radio on a table nearby.” I mean, really, who the hell starts dancing just to pass the time, and who dances to the “faint sound of rock music?” Once or twice the writing veers into the creepy zone, as when Lawrence declares, “My, what a fine figure of a woman!” when you take off your clothes preparatory to taking a bath. But mostly it manages to be quaint and nostalgically charming with its mixture of Girl Power and romantic teenage giddiness.

"My fiance, Lord Jack Tresyllian," Tamara introduces him. "Jack, this is my friend from the States, Miss Nancy Drew."

"So you're that famous young sleuth whom the Yanks call Miss Sherlock!" says Lord Jack. "Tammy's told me about the mysteries you've solved -- but she never let on you looked so smashing! Welcome to Cornwall, Nancy luv!"

Before you know it, he sweeps you into his arms and kisses you warmly! Let's hope Tamara doesn't mind -- but for the moment all you can see are Lord Jack's dazzling sapphire-blue eyes.

Considered as an Infocom game rather than a Nancy Drew novel, however, Moonmist is afflicted with a terminal identity crisis. Infocom had been making a dangerous habit of conflating the idea of an introductory-level game for adults with that of a game for children for some time already by the time it appeared. Seastalker, the first game to explicitly identify itself as a kinder, gentler Infocom product, had originally been marketed upon its release in June of 1984 as a story for children, trailblazer for a whole line of “Interactive Fiction Junior” that would hopefully soon be selling madly to the same generation of kids that was snapping up Choose Your Own Adventure paperbacks by the millions. Sadly, that never happened — doubtless not least because a Choose Your Own Adventure book cost $2 or so, Seastalker $30 or more. Upon the release exactly one year later of Brian Moriarty’s Wishbringer, an introductory-level game written using the same adult diction of most of Infocom’s other games, the “Junior” line was quietly dropped and Seastalker relabeled to join Wishbringer as an “Introductory” game, despite the fact that the two were quite clearly different beasts entirely. Then, in October of 1986, Moonmist was also released as simply an adult “Introductory” game — but, as just about the entire article that precedes this paragraph attests, Jim Lawrence and Stu Galley apparently didn’t get a memo somewhere along the line. Moonmist the digital artifact was, in opposition to Moonmist the marketing construct, plainly children’s literature. At best — particularly if she used to read Nancy Drew — the adult player was likely to find Moonmist nostalgically charming. At worst, it could read as condescending. Any computer game released into the cutthroat industry of 1986 was facing a serious problem if it didn’t know exactly what it was and whom could be expected to buy it. Moonmist, alas, wasn’t quite sure of either.

That said, Moonmist actually did somewhat better than one might have expected given this confusion. Its final sales would end up at around 33,000 copies, worse than those of Seastalker but not dramatically so. There’s good reason for its modern status as one of Infocom’s less-remembered and less-loved games: it’s definitely one of the slighter works in the canon. Certainly only hardcore fans are likely to summon the motivation to complete all four cases. Despite its shortcomings, though, others may find it worth sampling one or two cases, and historians may be interested in experiencing this early interactive take on Nancy Drew published many years before the long-running — indeed, still ongoing — series of graphic adventures that Her Interactive began releasing in the late 1990s.

Moonmist would mark the last time that Stu Galley or Jim Lawrence would be credited as the author of an Infocom game. Lawrence returned to print fiction, where he could make a lot more money a lot more quickly than he could writing text adventures. Galley remained at Infocom until the bitter end, working on technology and on one or two more game ideas that would frustratingly never come to fruition. Given just how in love he was with the potential of interactive fiction, it does seem a shame that he never quite managed to write a game that hit it out of the park. On the other hand, his quiet enthusiasm and wisdom probably contributed more than any of us realize to many of those Infocom games that did.

(In addition to the Get Lamp interviews, this article draws from some of the internal emails and other documents that were included on the Masterpieces of Infocom CD. An interview with Galley in the June 1986 issue of Zzap! was also useful.)