It’s all but impossible to overstate the influence that Star Wars had on the first generation of microcomputer games. The fact is, Star Wars and early home computers were almost inseparable — in some odd sense part of the same larger cultural movement, if you will.

The first film in George Lucas’s blockbuster trilogy debuted on May 25, 1977, just days before the Apple II, the first pre-assembled personal computer to be marketed to everyday consumers, reached store shelves. If not everyone who loved Star Wars had the money and the desire to buy a computer in the months and years that followed, it did seem that everyone who bought a computer loved Star Wars. And that love in turn fueled many of the games those early adopters made. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings novels and, perhaps more arguably, the Star Trek television and movie franchise are the only other traditional-media properties whose impact on the fictions and even mechanics of early computer games can be compared to that of Star Wars.

And yet licensed takes on all three properties were much less prominent than one might expect from the degree of passion the home-computer demographic had for them. The British/Australian publisher Melbourne House had a huge worldwide hit with their rather strange 1982 text-adventure adaptation of Tolkien’s The Hobbit, but never scaled similar heights with any of their mediocre follow-ups. Meanwhile Star Trek wound up in the hands of the software arm of the print publisher Simon & Schuster, who released a series of obtuse, largely text-based games that went absolutely nowhere. And as for Star Wars, the hottest property of them all… ah, therein lies a tale.

Like The Lord of the Rings before it, Star Wars was a victim of the times in which its first licensing deals were signed. In the months before the first movie was released, both George Lucas himself and 20th Century Fox, the studio that distributed the film, sought after someone — anyone — who would be willing to make a line of toys to accompany it. They were turned down again and again. Finally, Marc Pevers, Fox’s president of licensing, got a nibble from a small toy maker called Kenner Products.

Kenner was owned at that time by the big corporate conglomerate General Mills, who also happened to own Parker Brothers, the maker of such family-board-game staples as Monopoly, Clue, and Sorry!. Thus when Kenner negotiated with Lucas and Fox, they requested that the license cover “toys and [emphasis mine] games,” with responsibility for the latter to be kicked over to Parker Brothers. For at this early date, before the release of the Atari VCS videogame console, before even the arrival of Space Invaders in American arcades, “games” meant board games in the minds of everyone negotiating the deal. Indeed, Kenner explicitly promised that at a minimum they would produce four action figures and a “family game” to help prime the pump of a film whose commercial prospects struck just about everyone as highly dubious.

There are conflicting reports as to the other terms of the deal, but it seems most likely that Kenner agreed to pay Lucas and Fox either a 5-percent royalty or a flat $100,000 per year, whichever amount was greater. If Kenner ever failed to pay at least $100,000 in any given year, the arrangement would end immediately. Otherwise, it would go on in perpetuity. It was quite a sweet deal for Kenner by any standard, very much a reflection of the position of weakness from which Fox and Lucas were negotiating; one Kenner employee later joked that they had gotten Star Wars for “$50 and a handshake.”

Of course, we all know what happened with that first Star Wars film upon its release a few months after the contract was signed. After a slow start in 1977 while they tooled up to meet the completely unexpected level of demand, Kenner sold 42 million pieces of Star Wars-branded merchandise in 1978 alone; by 1985, the worldwide population of Star Wars action figures was larger than the United States’s population of real human beings. Lucas publicly excoriated Marc Pevers for a deal that had cost him “tens of millions,” and the two wound up in libel court, the former eventually forced to pay the latter an unspecified sum for his overheated remarks by a settlement arrangement.

Lucas’s anger was understandable if not terribly dignified. As if the deal for the toy rights alone wasn’t bad enough, Pevers had blithely sold off the videogame rights for a song as well, simply by not demanding more specific language about what kinds of games the phrase “toys and games” referred to. Kenner’s first attempt at a Star Wars videogame came already in 1978, in the form of a single-purpose handheld gadget subtitled Electronic Laser Battle. When that didn’t do well, the field was abandoned until 1982, when, with the Atari-VCS-fueled first wave of digital gaming at its height, Parker Brothers released three simple action games for the console. Then they sub-contracted a few coin-op arcade games to Atari, who ported them to home consoles and computers as well.

But by the time the last of these appeared, it was 1985, the Great Videogame Crash was two years in the past, and it seemed to the hidebound executives at General Mills that the fad for videogames was over and done with, permanently. Their Star Wars games had done pretty well for themselves, but had come out just a little too late in the day to really clean up. So be it; they saw little reason to continue making them now. It would be six years before another all-new, officially licensed Star Wars videogame would appear in North America, even as the virtual worlds of countless non-licensed games would continue to be filled with ersatz Han Solos and Death Stars.

This state of affairs was made doubly ironic by the fact that Lucasfilm, George Lucas’s production company, had started its own games studio already in 1982. For most of its first ten years, the subsidiary known as Lucasfilm Games was strictly barred from making Star Wars games, even as its employees worked on Skywalker Ranch, surrounded with props and paraphernalia from the films. Said employees have often remarked in the years since that their inability to use their corporate parent’s most famous intellectual property was really a blessing in disguise, in that it forced them to define themselves in other ways, namely by creating one of the most innovative and interesting bodies of work of the entire 1980s gaming scene. “Not being able to make Star Wars games freed us, freed us in a way that I don’t think we understood at the time,” says Ron Gilbert, the designer of the Lucasfilm classics Maniac Mansion and The Secret of Monkey Island. “We always felt we had to be making games that were different and pushed the creative edges. We felt we had to live up to the Lucasfilm name.” For all that, though, having the Lucasfilm name but not the Star Wars license that ought to go with it remained a frustrating position to be in, especially knowing that the situation was all down to a legal accident, all thanks to that single vaguely worded contract.

If the sequence of events which barred Lucasfilm from making games based on their own supreme leader’s universe was a tad bizarre, the way in which the Star Wars rights were finally freed up again was even stranger. By the end of 1980s, sales of Star Wars toys were no longer what they once had been. The Return of the Jedi, the third and presumably last of the Star Wars films, was receding further and further into the rear-view mirror, with nothing new on the horizon to reignite the old excitement for the next generation of children. For the first time, Kenner found themselves paying the guaranteed $100,000 licensing fee to Lucas and Fox instead of the 5-percent royalty.

At the beginning of 1991, Kenner failed to send the aforementioned parties their $100,000 check for the previous year, thereby nullifying the fourteen-year-old contract for Star Wars “toys and games.” Fan folklore would have it that the missing check was the result of an accounting oversight; Kenner was about to be acquired by Hasbro, and there was much chaos about the place. A more likely explanation, however, is that Kenner simply decided that the contract wasn’t worth maintaining anymore. The Star Wars gravy train had been great while it lasted, but it had run its course.

There was jubilation inside Lucasfilm Games when the staff was informed that at long last they were to be allowed to play in the universe of Star Wars. They quickly turned out a few simple action-oriented titles for consoles, but their real allegiance as a studio was to personal computers. Thus they poured the most effort by far into X-Wing, the first Star Wars game ever to be made first, foremost, and exclusively for computers, with all the extra complexity and extra scope for design ambition which that description implied in those days.

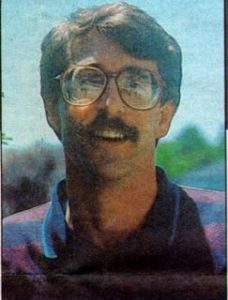

The mastermind of X-Wing was a soft-spoken, unassuming fellow named Lawrence Holland, whose path into the industry had been anything but straightforward. His first passion in life had been archaeology and anthropology; he’d spent much of his early twenties working in the field in remote regions of East Africa and India. In 1981, he came to the University of California, Berkeley to study for a doctorate in anthropology. He had never even seen a personal computer, much less played a computer game, until he became roommates with someone who had one. Holland:

I was working as a chef at a restaurant in Berkeley — and I realized I didn’t particularly want to do that for the next six years while I worked on my doctorate. At the time, my roommate had an Atari 800, and he was into programming. I thought, “Hey, what a cool machine!” So I finally got a Commodore 64 and spent all my spare time teaching myself how to use it. I’d always wanted to build something, but I just hadn’t found the right medium. Computers seemed to me to be the perfect combination of engineering and creativity.

The barriers to entry in the software industry were much lower then than they are today; a bright young mind like Holland with an aptitude and passion for programming could walk into a job with no formal qualifications whatsoever. He eventually dropped out of his PhD track in favor of becoming a staff programmer at HESWare, a darling of the venture capitalists during that brief post-Great Videogame Crash era when home computers were widely expected to become the Next Big Thing after the console flame-out.

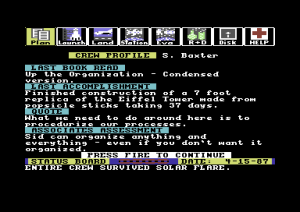

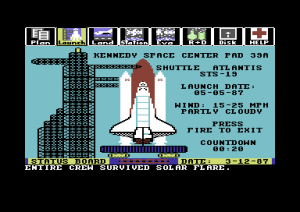

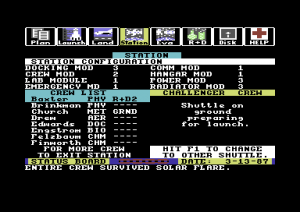

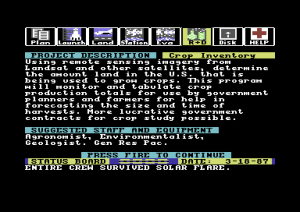

While working for HESWare in 1985, Holland was responsible for designing and programming a rather remarkable if not quite fully-realized game called Project: Space Station, a combination of simulation and strategy depicting the construction and operation of its namesake in low Earth orbit. But soon after its release HESWare collapsed, and Holland moved on to Lucasfilm Games. Throughout his many years there, he would work as an independent contractor rather than an employee, by his own choice. This allowed him, as he once joked, to “take classes and keep learning about history and anthropology in my copious spare time.”

In writing about the LucasFilm Games of the late 1980s and early 1990s in previous articles, I’ve focused primarily on the line of graphic adventures which they began in 1987 with Maniac Mansion, stressing how these games’ emphasis on fairness made them a welcome and even visionary alternative to the brutality being inflicted upon players by other adventure developers at the time. But the studio was never content to do or be just one thing. Thus at the same time that Ron Gilbert was working on Maniac Mansion, another designer named Noah Falstein was making a bid for the vehicular-simulation market, one of the most lucrative corners of the industry. Lawrence Holland came to Lucasfilm Games to help out with that — to be the technical guy who made Falstein’s design briefs come to life on the monitor screen. The first fruit of that partnership was 1987’s PHM Pegasus, a simulation of a hydrofoil attack boat; it was followed by a slightly more elaborate real-time naval simulation called Strike Fleet the following year.

With that apprenticeship behind him, Holland was allowed to take sole charge of Battlehawks 1942, a simulation of World War II aerial combat in the Pacific Theater. He designed and programmed the game in barely six months, in time to see it released before the end of 1988, whereupon it was promptly named “action game of the year” by Computer Gaming World magazine. Battlehawks 1942 was followed in 1989 by Their Finest Hour, another winner of the same award, a simulation of the early air war in Europe; it was in turn followed by 1991’s Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe, a simulation of the later years of war there. Each simulator raised the ante over what had come before in terms of budget, development time, and design ambition.

The Early Works of Lawrence Holland

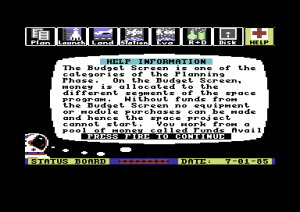

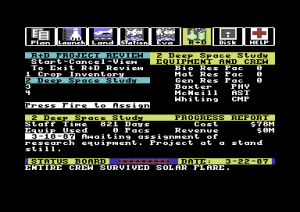

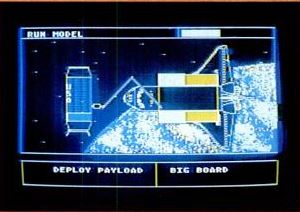

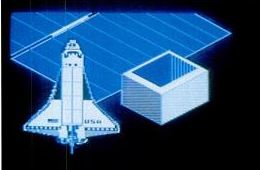

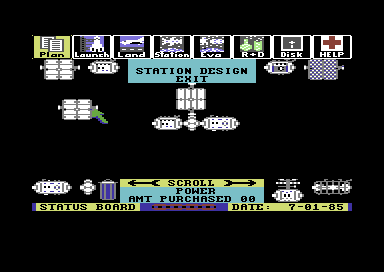

Project: Space Station (1985) is an amazingly complex simulation and strategy game for the humble Commodore 64. Holland took the project over after an earlier version that was to have been helmed by a literal rocket scientist fell apart, scaling down the grandiose ideas of his predecessor just enough to fit them into 64 K of memory.

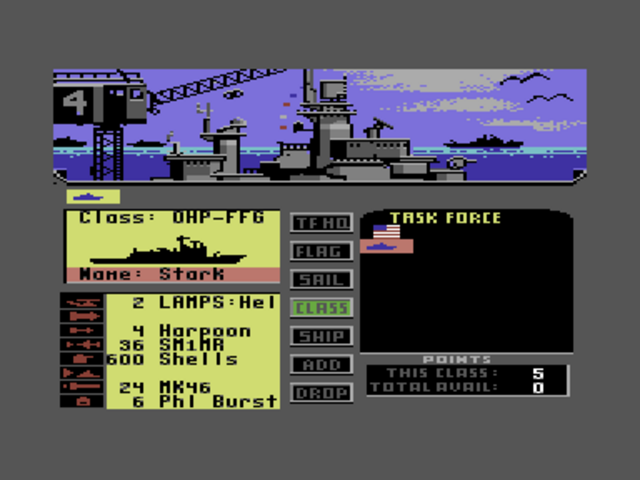

PHM Pegasus (1987) was designed by Noah Falstein and implemented by Holland. It simulates a military hydrofoil — sort of the modern equivalent to the famous PT Boats of World War II.

Strike Fleet (1988), Holland’s second and last game working with Falstein as lead designer, expands on the concept of PHM Pegasus to let the player lead multiple ships into fast-paced real-time battles.

Battlehawks 1942 (1988) was Holland’s first flight simulator, his first project for LucasArts on which he served as lead designer as well as programmer, and the first which he coded on MS-DOS machines rather than the Commodore 64. A simulation of carrier-based aviation during the fraught early months of World War II in the Pacific, it was implemented in barely six months from start to finish. Dick Best, the leader of the first dive-bomber attack on the Japanese aircraft carriers at the Battle of Midway — and thus the tip of the spear which changed the course of the war — served as a technical advisor. “I am thinking about buying an IBM just so I can play the game at home,” said the 78-year-old pilot to journalists.

Their Finest Hour (1989) was the second game in what would later become known as Holland’s “air-combat trilogy.” A portrayal of the Battle of Britain, it added a campaign mode, a selection of set-piece historical missions to fly, and even a mission builder for making more scenarios of your own to share with others.

Holland’s ambition ran wild in Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe (1991). Beginning as a simulation of such oddball latter-war German aircraft as the Messerschmitt Me-163 rocket plane and the Me-262 jet fighter, it wound up encompassing the entire second half of the air war in Europe, including a strategy game about the Allied strategic-bombing campaign that was detailed enough to have been put in a separate box and sold alone. As much a gaming toolbox as a game, it was supported with no fewer than four separate expansion packs. Holland and Edward Kilham, his programming partner for the project, crunched for a solid year to finish it, but nevertheless ended a good twelve months behind schedule. With this object lesson to think back on, Holland would rein in his design ambitions a bit more in the future.

As I described at some length in a recent article, flight simulators in general tend to age more like unpasteurized milk than fine wine, and by no means is Holland’s work in this vein entirely exempt from this rule. Still, in an age when most simulators were emphasizing cutting-edge graphics and ever more complexity over the fundamentals of game design, Holland’s efforts do stand out for their interest in conveying historical texture rather than a painstakingly perfect flight model. They were very much in the spirit of what designer Michael Bate, who used a similar approach at a slightly earlier date in games he made for Accolade Software, liked to call “aesthetic simulations of history.” Holland:

Flight simulators [had] really focused on the planes, rather than the times, the people, and how the battles influenced the course of the war. [The latter is] what I set out to do. It’s become my philosophy for all the sims I’ve done.

We get letters from former pilots, who say, “Wow! This is great! This is just like I remember it.” They’re talking about a gut, sensory impression about the realism of flying and interacting with other planes — not the hardcore mathematical models. I’ve focused on that gut feeling of realism rather than the hardcore mathematical stuff. I’ve emphasized plane-to-plane engagement, seat-of-the-pants flying. I like to keep the controls as simple as possible, so someone can jump in and enjoy the game. Of course, the more technically accurate the flight model, the more difficult it is to fly. Unless they’re really familiar with flight simulators, people tend to be intimidated by having to learn the uses of a bunch of different keys. That makes a game hard to get into. I want them to be able to hop into the cockpit and fly.

In some ways at least, Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe remains to this day the most ambitious game Lawrence Holland has ever made. At a time when rival flight simulators like Falcon were going micro, attempting to capture a single aircraft with a pedant’s obsession for detail, Secret Weapons provided a macro-level overview of the entire European air war following the entry of the United States into the conflict. Holland called it a “kitchen-sink” game: “It’s fun and challenging to keep thinking of different ways for the player to interact with the product on different levels.” In Secret Weapons, you could pilot any of eight different airplanes, including the experimental German rocket planes and jets that gave the game its misleadingly narrow-sounding name, or even fly as a gunner or bombardier instead of a pilot in a B-17. You could go through flight school, fly a single random mission, a historical mission, or fly a whole tour of duty in career mode. Or you could play Secret Weapons as a strategy game of the Allied bombing campaign against Germany, flying the missions yourself if you liked or letting the computer handle that for you; this part of the game alone was detailed enough that, had it been released as a standalone strategy title by a company like SSI, no one would have batted an eye. And then there were the four (!) expansion packs LucasArts put together, adding yet more airplanes and things to do with them…

Of course, ambition can be a double-edged sword in game design. Although Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe came together much better in the end than many other kitchen-sink games, it also came in a year late and way over budget. As it happened, its release in late 1991 came right on the heels of the news that Lucasfilm Games was finally going to be allowed to charge into the Star Wars universe. Lawrence Holland’s life was about to take another unexpected twist.

It isn’t hard to figure out why LucasArts — the old Lucasfilm Games adopted the new name in 1992 — might have wished to create a “simulation” of Star Wars space battles. At the time, the biggest franchise in gaming was Origin Systems’s Wing Commander series, which itself owed more than a little to George Lucas’s films. Players loved the action in those games, but they loved at least equally the storytelling which the series had begun to embrace with gusto in 1991’s Wing Commander II. A “real” Star Wars game offered the chance to do both things as well or better, by incorporating both the spacecraft and weapons of the films and the established characters and plot lore of the Star Wars universe.

Meanwhile the creative and technical leap from a simulation of World War II aerial combat to a pseudo-simulation of fictional space combat was shorter than one might initially imagine. The label of space simulator was obviously a misnomer in the strictly literal sense; you cannot simulate something which has never existed and never will. (If at some point wars do move into outer space, they will definitely not be fought anything like this.) Nevertheless, X-Wing would strive to convey that feeling of realism that is the hallmark of a good aesthetic simulation. It wouldn’t, in other words, be an arcade game like the Star Wars games of the previous decade.

In point of fact, George Lucas had aimed to capture the feel of World War II dogfighting in his movies’ action sequences, to the point of basing some shots on vintage gun-camera footage. It was thus quite natural to build X-Wing upon the technology last seen in Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe. You would have to plan your attacks with a degree of care, would have to practice some of the same tactics that World War II fighter pilots employed, would even have to manage the energy reserves of your craft, deciding how much to allocate to guns, shields, and engines at any given juncture.

Still working with LucasArts as an independent contractor, Holland hired additional programmers Peter Lincroft and Edward Kilham — the former had also worked on Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe — to help him out with the project. LucasArts’s in-house staff of artists and composers saw to the audiovisual assets, and their in-house designers developed most of the missions. With the struggle that his last game had been still high in his memory, and knowing all too well that LucasArts’s first Star Wars computer game needed to be released in a timely fashion if it was to compete with the Wing Commander juggernaut, Holland abandoned any thoughts of dynamic campaigns or overarching strategic layers in favor of a simple series of set-piece missions linked together by a pre-crafted story line — exactly the approach that had won so much commercial success for Wing Commander. In fact, Holland simplified the Wing Commander approach even further, by abandoning its branching mission tree in favor of a keep-trying-each-mission-until-you-win-it methodology. (To be fair, market research proved that most people played Wing Commander this way anyway…)

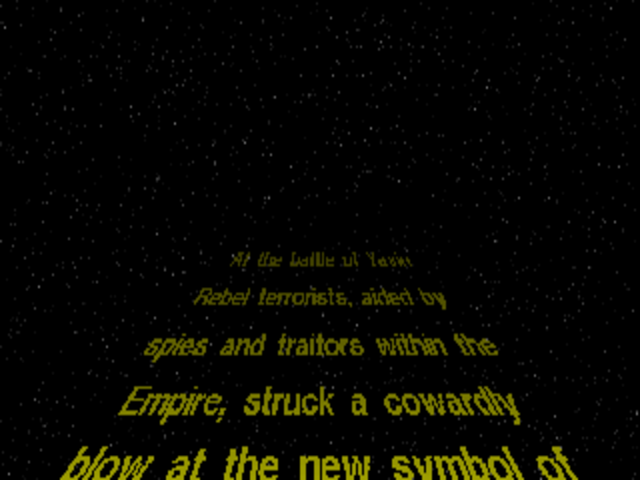

X-Wing‘s not-so-secret weapon over its great rival franchise was and is, to state it purely and simply, Star Wars. Right from the iconic flattened text crawl that opens the game, accompanied by the first stirring chords of John Williams’s unforgettable theme music, it looks like Star Wars, sounds like Star Wars, feels like Star Wars. The story it tells is interwoven quite deftly with the plot of the first film. It avoids the slightly ham-handed soap-opera story lines which Wing Commander loves to indulge in in favor of a laser focus on the real business at hand: the destruction of the Death Star. Whereas Wing Commander, with its killer alien cats and all the rest, never rises much above the level of earnest fan fiction, X-Wing is… well, it certainly isn’t great literature, any more than the films upon which it’s based are profound drama, but it is solidly crafted pulp fiction for the kid in all of us, and this quality makes it exactly like the aforementioned films. Playing it really does feel like jumping into one of them.

But X-Wing also has an Achilles heel that undoes much of what it does so well, a failing that’s serious enough that I have trouble recommending the game at all: its absolutely absurd level of difficulty. As you advance further in the game, its missions slowly reveal themselves to be static puzzles to be solved rather than dynamic experiences. There’s just one way to succeed in the later missions in particular, just one “correct” sequence of actions which you must carry out perfectly. You can expect to fly each mission over and over while you work out what that sequence is. This rote endeavor is the polar opposite of the fast-paced excitement of a Star Wars film. As you fail again and again, X-Wing gradually becomes the one thing Star Wars should never be: it becomes boring.

There’s a supreme irony here: LucasArts made their name in adventure games by rejecting the idea that the genre must necessarily entail dying over and over and, even worse, stumbling down blind alleys from which you can never return without restoring or restarting. But with X-Wing, the company famous for “no deaths and no dead ends” delivered a game where you could effectively lock yourself out of victory in the first minute of a mission. It’s hard to conceive of why anyone at LucasArts might have thought this a good approach. Yet Computer Gaming World‘s Chris Lombardi was able to confirm in his eventual review of the game that the punishing mission design wasn’t down to some colossal oversight; it was all part of the plan from the beginning.

Through an exchange with LucasArts, I’ve learned from them that the missions were designed as puzzles to be figured out and solved. This is entirely accurate. The tougher missions have a very specific “solution” that must be executed with heroic precision. Fly to point A, knock out fighters with inhuman accuracy, race to point B, knock out bombers with same, race to point C, to nip off a second bomber squadron at the last possible second. While this is extremely challenging and will make for many hours of play, I’m not convinced that it’s the most effective design possible. It yanks [the player] out of the fiction of the game when he has to play a mission five times just to figure out what his true objective is, and then to play the next dozen times trying to execute the path perfectly.

Often, success requires [the player] to anticipate the arrival of enemy units and unrealistically race out into space to meet a “surprise” attack from the Empire. It’s all a matter of balance, young Jedi, and on the sliding scale of Trivially Easy to Joystick-Flinging Frustration, X-Wing often stumbles awkwardly toward the latter. From the reviewer’s high ground of hindsight, it seems a player-controlled difficulty setting might have been a good solution.

Despite this tragic flaw lurking at its mushy center, X-Wing was greeted with overwhelmingly positive reviews and strong sales upon its release in March of 1993. For, if X-Wing left something to be desired as a piece of game design, the timing of its release was simply perfect.

The game hit the scene in tandem with a modest but palpable resurgence of interest in Star Wars as a whole. In 1991 — just as Kenner Products was deciding that the whole Star Wars thing had run its course — Timothy Zahn had published Heir to the Empire, the first of a new trilogy of Star Wars novels. There had been Star Wars books before, of course, but Zahn’s trilogy was unique in that, rather than having to confine himself to side stories so as not to interfere with cinematic canon, its author had been given permission by George Lucas to pick up the main thread of what happened after Return of the Jedi. Everyone who read the trilogy seemed to agree that it represented a very credible continuation indeed, coming complete with an arch-villain, one Imperial Grand Admiral Thrawn, who was almost as compelling as Darth Vader. All three books — the last of them came out in 1993, just after X-Wing — topped genre-fiction bestseller lists. Star Wars was suddenly having a moment again, and X-Wing became a part of that, both as beneficiary and benefactor. Many of the kids who had seen the films multiple times each in theaters and carried Star Wars lunchboxes with them to school were now in their early twenties, the sweet spot of the 1993 computer-game demographic, and were now feeling the first bittersweet breaths of nostalgia to blow through their young lives, even as they were newly awakened to the potential of space simulators in general by the Wing Commander games. How could X-Wing not have become a hit?

The people who had made the game weren’t much different from the people who were now buying it in such gratifying numbers. Zahn’s novels were great favorites of Holland and his colleagues as well, so much so that, when the time came to plan the inevitable sequel to X-Wing, they incorporated Admiral Thrawn into the plot. In the vastly superior game known as TIE Fighter, which takes places concurrently with the second Star Wars film, a younger Thrawn appears in the uneasy role of subordinate to Darth Vader.

Indeed, it’s difficult to imagine TIE Fighter, which dares to place you in the role of a pilot for the “evil” Empire, ever coming to exist at all without the Zahn novels. For it was Zahn’s nuanced, even sympathetic portrayal of Thrawn, and with it his articulation of an ideology for the Empire that went beyond doing evil for the sake of it, that first broadened the moral palette of the Star Wars universe to include shades of gray in addition to black and white. Zahn’s version of the Empire is a rather fussily bureaucratic entity that sees itself as tamping down sectarianism and maintaining law and order in the galaxy in the interest of the greater good, even if the methods it is sometimes forced to employ can be regrettably violent. The game took that interpretation and ran with it. Holland:

Our approach is that the propaganda machines are always running full-blast during warfare. So far, the propaganda we’ve been exposed to has been from the Rebels. But in warfare, neither side is always clean, and both sides can take the moral high ground. So we’re trying to blur the moral line a little bit and give the Empire a soapbox to communicate its mission: the restoration of peace and order.

For instance, there’s a lot of civil war going on. The fighting planets are lost in their hate and don’t have the galactic perspective the Empire can provide. In this regard, the Empire feels it can serve to stop these conflicts. Within the Empire there are a lot of people — like the pilot the player portrays — who have an honorable objective.

At the risk of putting too fine a point on it: I would hardly be the first Internet scribe to note that the established hegemony of developed Western nations in our own world resembles the Empire far more than the Rebel Alliance, nor that the Rebel freedom fighters bear a distinct similarity to some of the real-world folks we generally prefer to call terrorists.

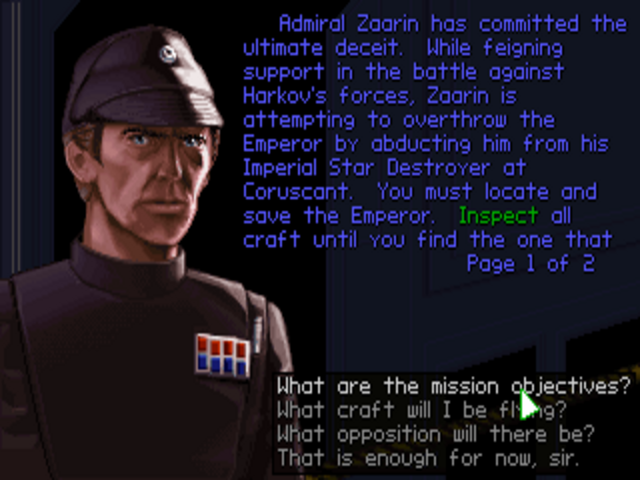

TIE Fighter casts you as a pilot of good faith who earnestly believes in the Empire’s professed objective of an orderly peace and prosperity that will benefit everyone. In order to capture some of the murderous infighting that marks the highest levels of the Imperial bureaucracy in both the movies and Zahn’s novels, as well as to convey some of the moral rot taking cover beneath the Empire’s professed ideology, the game introduces a mysterious agent of the emperor himself who lurks in the shadows during your mission briefings, to pull you aside afterward and give you secret objectives that hint of machinations and conspiracies that are otherwise beyond your ken. In the end, you find yourself spending almost as much time fighting other factions of the Empire as you do Rebels — which does rather put the lie to the Empire’s claim that only it can provide a harmonious, orderly galaxy, but so be it.

What really makes TIE Fighter so much better than its predecessor is not the switch in perspective, brave and interesting though it may be, but rather the fact that it so comprehensively improves on X-Wing at the level of the nuts and bolts of game design. It’s a fine example of a development team actually listening to players and reviewers, and then going out and methodically addressing their complaints. In the broad strokes, TIE Fighter is the same game as X-Wing: the same linear series of missions to work through, the same basic set of flight controls, a different but similarly varied selection of spacecraft to learn how to employ successfully. It just does everything that both games do that much better than its predecessor.

Take, for example, the question of coordinating your tactics with your wingmen and other allies. On the surface, the presence of friends as well as foes in the battles you fight is a hallmark not just of X-Wing but of the Wing Commander games that came before it, being embedded into the very name of the latter series. Yet your helpmates in all of those games are, as Chris Lombardi put it in his review of X-Wing, “about as useful as a rowboat on Tatooine.” Players can expect to rack up a kill tally ten times that of their nearest comrade-in-arms.

TIE Fighter changes all that. It presents space battles that are far more complex than anything seen in a space simulator before it, battles where everyone else flies and fights with independent agency and intelligence. You can’t do everything all by yourself anymore; you have to issue real, substantive orders to the pilots you command, and obey those orders that are issued to you. Many reviewers of TIE Fighter have pointed out how well this ethos fits into that of a hyper-organized, hyper-disciplined Imperial military, as opposed to the ramshackle individual heroism of the Rebel Alliance. And it’s certainly a fair point, even if I suspect that the thematic resonance may be more a happy accident than a conscious design choice. But whatever the reasons behind it, it lends TIE Fighter a different personality. Instead of being the lone hero who has to get everything done for yourself, you feel like a part of a larger whole.

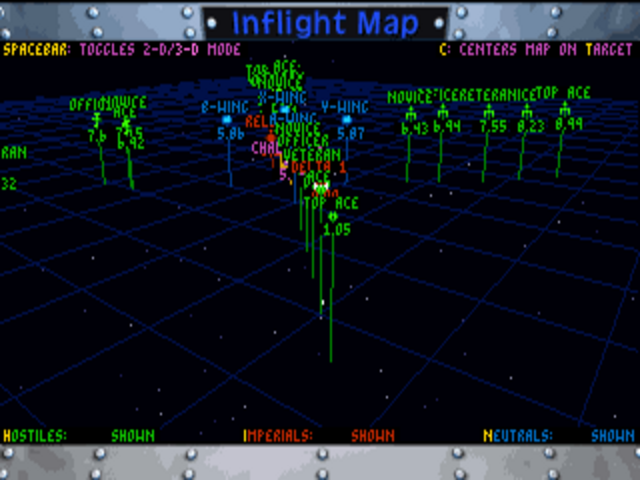

For the developers, the necessary prerequisites to success with this new philosophy were an improved technical implementation and improved mission design in comparison to those of X-Wing. In addition to the audiovisual evolution that was par for the course during this fast-evolving era of computing — the 3D models are now rendered using Gouraud shading — TIE Fighter gives you a whole range of new views and commands to make keeping track of the overall flow of battle, keeping tabs on your allies, and orienting yourself to your enemies much easier than in X-Wing. Best of all, it abandons the old puzzle-style missions in favor of the unfolding, dynamic battlescapes we were missing so keenly last time. It does you the small but vital kindness of telling you which mission objectives have been completed and which still need to be fulfilled, as well as telling you when a mission is irrevocably failed. It also introduces optional objectives, so that casual players can keep the story going while completists try to collect every last point. And it has three difficulty levels to choose from rather than being permanently stuck on “Hard.”

TIE Fighter was released in July of 1994, five months before the long-awaited Wing Commander III, a four-CD extravaganza featuring a slate of established actors onscreen, among them Mark Hamill, Mr. Luke Skywalker himself. LucasArts’s game might have seemed scanty, even old-fashioned by comparison; it didn’t even ship on the wundermedium of CD at first, but rather on just five ordinary floppy disks. Yet it sold very well, and time has been much kinder to it than it has to Origins’s trendier production, which now seems somehow more dated than the likes of Pong. TIE Fighter, on the other hand, remains what it has always been: bright, pulpy, immersive, exciting, Star Warsy fun. It’s still my favorite space simulator of all time.

TIE Fighter

How could it be Star Wars without that iconic opening text crawl? TIE Fighter and its predecessor succeed brilliantly in feeling like these movies that define the adjective “iconic.” This extends to the sound design: the whoosh of passing spacecraft and closing pneumatic doors, the chatter of droids, the various themes of John Williams’s soundtrack… it’s all captured here with remarkable fidelity to the original. Of course, there are some differences: the sequence above is initially jarring because it’s accompanied by Williams’s ominous Imperial theme rather than the heroic main Rebel theme which we’ve been conditioned to expect.

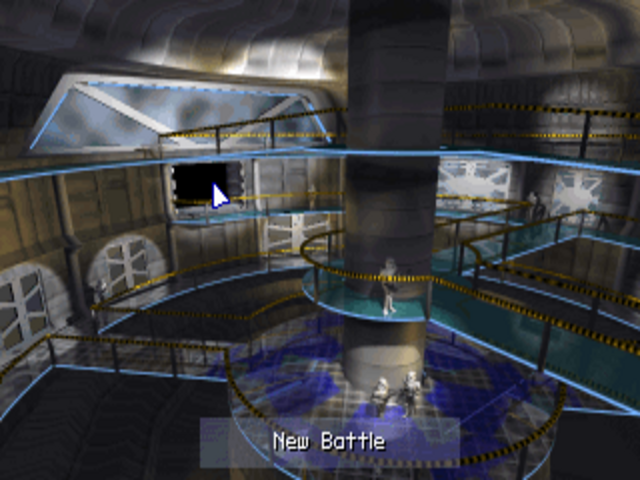

One of the many places where TIE Fighter borrows from Wing Commander is in its commitment to a diegetic interface. You don’t choose what to do from a conventional menu; you decide whether you want to walk to the training simulator, briefing room, film room, etc.

The staff of LucasArts were big fans of Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire trilogy of novels. Thus Grand Admiral Thrawn, the books’ most memorable character, shows up as a younger Imperial officer here.

TIE Fighter‘s in-flight graphics weren’t all that spectacular to look at even by the standards of their day, given that they were implemented in standard VGA rather than higher-resolution SVGA. Wing Commander III, which appeared the same year, did embrace SVGA, and looked much better for it. Luckily, TIE Fighter had other things working in its favor…

Having decided to present the most complex battles yet seen in a space simulator, TIE Fighter needed to provide new ways of keeping track of them if it was to remain playable. Thankfully, the developers were up to the task, devising a whole array of clever command-and-control tools for your use.

You wind up spending almost as much time fighting other Imperial factions as “Rebel scum.” Call it a cop-out if you must…

You fly the climactic final mission side by side with Darth Vader. Unable to secure the services of James Earl Jones to voice the role, LucasArts had to settle for a credible soundalike. (Ironically, Jones did agree to provide voice acting for a game in 1994, but it wasn’t this one: it was Access Software’s adventure game Under a Killing Moon. He reportedly took that gig at a discount because his son was a fan of Access’s games.)

Both X-Wing and TIE Fighter later received a “collector’s edition” on CD-ROM, which added voice acting everywhere and support for higher-resolution Super VGA graphics cards, and also bundled in a lot of additional content, in the form of the two expansions that had already been released for X-Wing, the single TIE Fighter expansion, and some brand new missions. These are the versions you’ll find on the digital storefronts of today.

Time has added a unique strain of nostalgia to these and the other early LucasArts Star Wars games. During their era there was still an innocent purity to Star Wars which would be lost forever when George Lucas decided to revive the franchise on the big screen at decade’s end. Those “prequel” films replaced swashbuckling adventure with parliamentary politics, whilst displaying to painful effect Lucas’s limitations as a director and screenwriter. In so thoroughly failing to recapture the magic of what had come before, they have only made memories of the freer, breezier Star Wars of old burn that much brighter in the souls of old-timers like me. LucasArts’s 1990s Star Wars games were among the last great manifestations of that old spirit. The best few of them at least — a group which most certainly includes TIE Fighter — remain well worth savoring today.

(Sources: the books How Star Wars Conquered the Universe by Chris Taylor, Droidmaker: George Lucas and the Digital Revolution by Michael Rubin, and the X-Wing and TIE Fighter Collector’s Edition strategy guides by Rusel DeMaria, David Wessman, and David Maxwell; Game Developer of February/March 1995 and April/May 1995; Compute! of March 1990; Computer Gaming World of April 1988, November 1988, October 1989, January 1990, September 1990, December 1990, November 1991, February 1992, September 1992, June 1993, October 1993, February 1994, October 1994, and July 1995; PC Zone of April 1993; Retro Gamer 116; LucasArts’s customer newsletter The Adventurer of Fall 1990, Spring 1991, Fall 1991, Spring 1992, Fall 1992, Spring 1993, and Summer 1994; Seattle Times of December 25 2017; Fortune of August 18 1997. Also useful was the Dev Game Club podcast’s interview with Lawrence Holland on January 11, 2017.

X-Wing and TIE Fighter are available as digital purchases on GOG.com.)