We’ve seen how the pundits had already started speculating like crazy long before the actual release of IBM’s TopView, imagining it to be the key to some Machiavellian master plan for seizing complete control of the personal-computer market. But said pundits were giving IBM a bit more credit than perhaps was due. The company nicknamed Big Blue was indeed a big, notoriously bureaucratic place, and that reality tended to interfere with their ability to carry out any scheme, Machiavellian or otherwise, with the single-minded focus of a smaller company. There doubtless were voices inside IBM who could imagine using TopView as a way of shoving Microsoft aside, and had the product been a roaring success those voices doubtless would have been amplified. Yet thanks to the sheer multiplicity of voices IBM contained, the organization always seemed to be pulling in multiple directions at once. Thus even before TopView hit the market and promptly fizzled, a serious debate was taking place inside IBM about the long-term future direction of their personal computers’ system software. This particular debate didn’t focus on extensions to MS-DOS — not even on an extension like TopView which might eventually be decoupled from the unimpressive operating system underneath it. The question at hand was rather what should be done about creating a truly holistic replacement for MS-DOS. The release of a new model of IBM personal computer in August of 1984 had given that question new urgency.

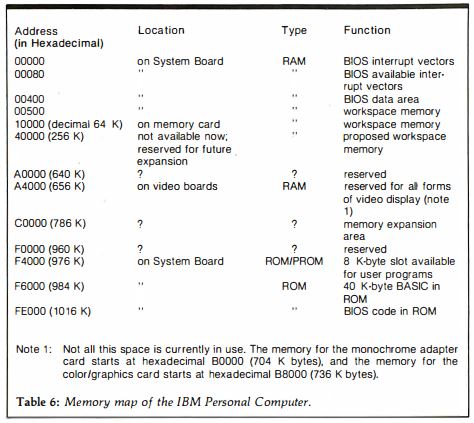

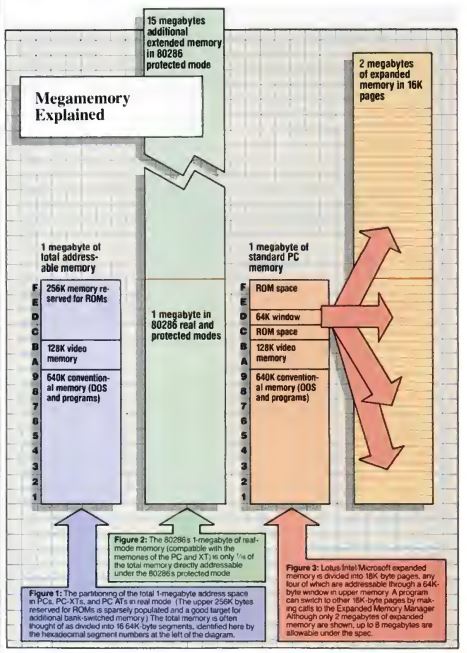

The PC/AT, the first really dramatic technical advance on the original IBM PC, used the new Intel 80286 processor in lieu of the older machine’s 8088. The 80286 could function in two modes. In “real” mode, grudgingly implemented by Intel’s engineers in the name of backward compatibility, it essentially was an 8088, with the important difference that it happened to run much faster. Otherwise, though, it shared most of the older chip’s limitations, most notably the ability to address only 1 MB of memory — the source, after the space reserved for system ROMs and other specialized functions was subtracted, of the original IBM PC’s limitation to 640 K of RAM. It was only in the 80286’s “protected” mode that the new chip’s full capabilities were revealed. In this mode, it could address up to 16 MB of memory, and implemented hardware memory protection ideal for the sort of modern multitasking operating system that MS-DOS so conspicuously was not.

The crux of IBM’s dilemma was that MS-DOS, being written for the 8088, could run on the 80286 only in real mode, leaving most of the new chip’s capabilities unused. Memory beyond 640 K could thus still be utilized only via inefficient and ugly hacks, even on a machine with a processor that, given a less clueless operating system, was ready and willing to address up to 16 MB. IBM therefore decided that sooner or later — and preferably sooner — MS-DOS simply had to go.

This much was obvious. What was less obvious was where this new-from-the-ground-up IBM operating system should come from. Over months of debate, IBM’s management broke down into three camps.

One camp advocated buying or licensing Unix, a tremendously sophisticated and flexible operating system born at AT&T’s Bell Labs. Unix was beloved by hackers everywhere, but remained under the thumb of AT&T, who licensed it to third parties with the wherewithal to pay for it. Ironically, Microsoft had had a Unix license for years, using it to create a product they called Xenix, by far the most widely used version of Unix on microcomputers during the early 1980s. Indeed, their version of Xenix for the 80286 had of late become the best way for ambitious users not willing to settle for MS-DOS to take full advantage of the PC/AT’s capabilities. Being an already extant operating system which Microsoft among others had been running on high-end microcomputers for years, a version of Unix for the business-microcomputing masses could presumably be put together fairly quickly, whether by Microsoft or by IBM themselves. Yet Unix, having been developed with bigger institutional computers in mind, was one heck of a complicated beast. IBM feared abandoning MS-DOS, with its user-unfriendliness born of primitiveness, only to run afoul of Unix’s user-unfriendliness born of its sheer sophistication. Further, Unix, having been developed for text-only computers, wasn’t much good for graphics — and thus not much good for GUIs. [1]Admittedly, this was already beginning to change as IBM was having this debate: the X Window project was born at MIT in 1984. The conventional wisdom held it to be an operating system better suited to system administrators and power users than secretaries and executives.

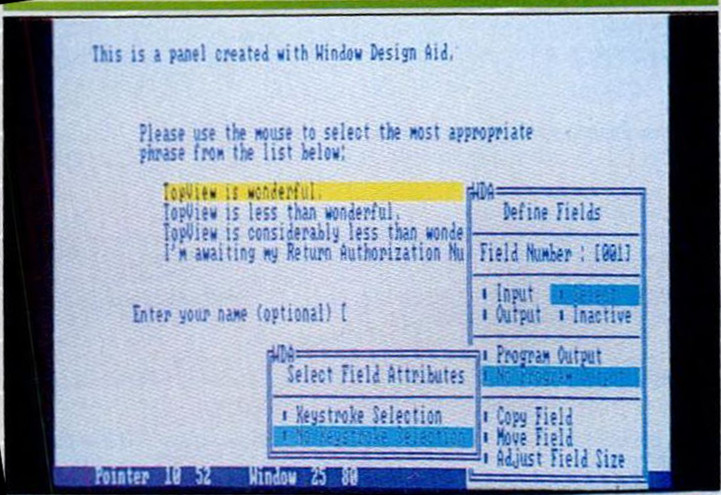

A second alternative was for IBM to make a new operating system completely in-house for their personal computers, just as they always had for their mainframes. They certainly had their share of programmers with experience in modern system software, along with various projects which might become the basis of a new microcomputer operating system. In particular, the debaters returned over and over again to one somewhat obscure model in their existing personal-computer lineup. Released in late 1983, the 3270 PC came equipped with a suite of additional hardware and software that let it act as a dumb terminal for a mainframe, while also running — simultaneously with multiple mainframe sessions, if the user wished — ordinary MS-DOS software. To accomplish that feat, IBM’s programmers had made a simple windowing environment that could run MS-DOS in one window, mainframe sessions in others. They had continued to develop the same software after the 3270 PC’s release, yielding a proto-operating system with the tentative name of Mermaid. The programmers who created Mermaid would claim in later years that it was far more impressive than either TopView or the first release of Microsoft Windows; “basically, in 1984 or so,” says one, “we had Windows 3.0.” But there was a big difference between Mermaid and even the latter, relatively advanced incarnation of Windows: rather than Mermaid running under MS-DOS, as did Windows, MS-DOS could run under Mermaid. MS-DOS ran, in other words, as just one of many potential tasks within the more advanced operating system, providing the backward compatibility with old software that was considered such a necessary bridge to any post-MS-DOS future. And then, on top all these advantages, Mermaid already came equipped with a workable GUI. It seemed like the most promising of beginnings.

By contrast, IBM’s third and last alternative for the long-term future initially seemed the most unappetizing by far: to go back to Microsoft, tell them they needed a new operating system to replace MS-DOS, and ask them to develop it with them, alongside their own programmers. There seemed little to recommend such an approach, given how unhappy IBM was already becoming over their dependency on Microsoft — not to mention the way the latter bore direct responsibility for the thriving and increasingly worrisome clone market, thanks to their willingness to license MS-DOS to anyone who asked for it. And yet, incredibly, this was the approach IBM would ultimately choose.

Why on earth would IBM choose such a path? One factor might have been the dismal failure of TopView, their first attempt at making and marketing a piece of microcomputer system software single-handedly, in the spring of 1985. Perhaps this really did unnerve them. Still, one has to suspect that there was more than a crisis of confidence behind IBM’s decision to go from actively distancing themselves from Microsoft to pulling the embrace yet tighter in a matter of months. In that light, it’s been reported that Bill Gates, getting wind of IBM’s possible plans to go it alone, threatened to jerk their existing MS-DOS license if they went ahead with work on a new operating system without him. Certainly IBM’s technical rank and file, who were quite confident in their own ability to create IBM’s operating system of the future and none too happy about Microsoft’s return to the scene, widely accepted this story at the time. “The bitterness was unbelievable,” remembers one. “People were really upset. Gates was raping IBM. It’s incomprehensible.”

Nevertheless, on August 22, 1985, Bill Gates and Bill Lowe, the latter being the president of IBM’s so-called “Entry Systems Division” that was responsible for their personal computers, signed a long-term “Joint Development Agreement” in which they promised to continue to support MS-DOS on IBM’s existing personal computers and to develop a new, better operating system for their future ones. All those who had feared that TopView represented the opening gambit in a bid by IBM to take complete control of the business-microcomputing market could breathe a sigh of relief. “We are committed to the open-architecture concept,” said Lowe, “and recognize the importance of this to our customers.” The new deal between the two companies was in fact far more ironclad and more equal than the one that had been signed before the release of the original IBM PC. “For Microsoft,” wrote the New York TImes‘s business page that day, “the agreement elevates it from a mere supplier to IBM, with the risk that it could one day be cut off, into more of a partner.” True equal partner with the company that in the eyes of many still was computing in the abstract… Microsoft was moving up in the world.

The public was shown only the first page or two of the new agreement, full of vague reassurances and mission statements. Yet it went on for many more pages after that, getting deep into the weeds of an all-new operating system to be called CP-DOS. (Curiously, the exact meaning of the acronym has never surfaced to my knowledge. “Concurrent Processing” would be my best guess, given the project’s priorities.) CP-DOS was to incorporate all of the sophistication that was missing from MS-DOS, including preemptive multitasking, virtual memory, the ability to address up to 16 MB of physical memory, and a system of device drivers to insulate applications from the hardware and insulate application programmers from the need to manually code up support for every new printer or video card to hit the market. So far, so good.

But this latest stage of an unlikely partnership would prove a very different experience for Microsoft than developing the system software for the original IBM PC had been. Back in 1980 and 1981, IBM, pressured for time, had happily left the software side of things entirely to Microsoft. Now, they truly expected to develop CP-DOS as partners with them, expected not only to write the specifications for the new operating system themselves but to handle some of the coding themselves as well. Two radically different corporate cultures clashed from the start. IBM, accustomed to carrying out even the most mundane tasks in bureaucratic triplicate, was appalled at the lone-hacker model of software development that still largely held sway at Microsoft, while the latter’s programmers held their counterparts in contempt, judging them to be a bunch of useless drones who never had an original thought in their lives. “There were good people” at IBM, admits one former Microsoft employee. But then, “there were a lot of not-so-good people also. That’s not Microsoft’s model. Microsoft’s model is only good people. If you’re not good, you don’t stick around.” Neal Friedman, a programmer on the CP-DOS team at Microsoft:

The project was extremely frustrating for people at Microsoft and for people at IBM too. It was a clash of two companies at opposite ends of the spectrum. At IBM, things got done very formally. Nobody did anything on their own. You went high enough to find somebody who could make a decision. You couldn’t change things without getting approval from the joint design-review committee. It took weeks even to fix a tiny little bug, to get approval for anything.

IBM measured their programmers’ productivity in the number of lines of code they could write per day. As Bill Gates and plenty of other people from Microsoft tried to point out, this metric said nothing about the quality of the code they wrote. In fact, it provided an active incentive for programmers to write bloated, inefficient code. Gates compared the project to trying to build the world’s heaviest airplane.

A joke memo circulated inside Microsoft, telling the story of an IBM rowing team that had lost a race. IBM, as was their wont, appointed a “task force” to analyze the failure. The bureaucrats assigned thereto discovered that the IBM team had had eight people steering and one rowing, while the other team had had eight people rowing and one steering. Their recommendation? Why, the eight steerers should simply get the one rower to row harder, of course. Microsoft took to calling IBM’s software-development methodology the “masses-of-asses” approach.

But, as only gradually became apparent to Microsoft’s programmers, Bill Gates had ceded the final authority on what CP-DOS should be and how it should be implemented to those selfsame masses of asses. Scott MacGregor, the Windows project manager during 1984, shares an interesting observation that apparently still applied to the Gates of 1985 and 1986:

Bill sort of had two modes. For all the other [hardware manufacturers], he would be very confident and very self-assured, and feel very comfortable telling them what the right thing to do was. But when he worked with IBM, he was always much more reserved and quiet and humble. It was really funny because this was the only company he would be that way with. In meetings with IBM, this change in Bill was amazing.

In charming or coercing IBM into signing the Joint Development Agreement, Gates had been able to perpetuate the partnership which had served Microsoft so well, but the terms turned out to be perhaps not quite so equal as they first appeared: he had indeed given IBM final authority over the new operating system, as well as agreeing that the end result would belong to Big Blue, not (as with MS-DOS) to Microsoft. As work on CP-DOS began in earnest in early 1986, a series of technical squabbles erupted, all of which Microsoft was bound to lose.

One vexing debate was over the nature of the eventual CP-DOS user interface. Rather than combining the plumbing of the new operating system and the user interface into one inseparable whole, IBM wanted to separate the two. In itself, this was a perfectly defensible choice; successful examples of this approach abound in computing history, from Unix and Linux’s X Windows to the modern Macintosh’s OS X. And of course this was an approach which Microsoft and many others had already taken in building GUI environments to run on top of MS-DOS. So, fair enough. The real disagreements started only when IBM and Microsoft started to discuss exactly what form CP-DOS’s preferred user interface should take. Unsurprisingly, Microsoft wanted to adapt Windows, that project in which they had invested so much of their money and reputation for so little reward, to run on top of CP-DOS instead of MS-DOS. But IBM had other plans.

IBM informed Microsoft that the official CP-DOS user interface at launch time was to be… wait for it… TopView. The sheer audacity of the demand was staggering. After developing TopView alone and in secret, cutting out their once and future partners, IBM now wanted Microsoft to port it to the new operating system the two companies were developing jointly. (Had they been privy to it, the pundits would doubtless have taken this demand as confirmation of their suspicion that at least some inside IBM had intended TopView to have an existence outside of its MS-DOS host all along.)

“TopView is hopeless,” pleaded Bill Gates. “Just let it die. A modern operating system needs a modern GUI to be taken seriously!” But IBM was having none of it. When they had released TopView, they had told their customers that it was here to stay, a fundamental part of the future of IBM personal computing. They couldn’t just abandon those people who had bought it; that would be contrary to the longstanding IBM ethic of being the safe choice in computing, the company you invested in when you needed stability and continuity above all else. “But almost nobody bought TopView in the first place!” howled Gates. “Why not just give them their money back if it’s that important to you?” IBM remained unmoved. “Do a good job with a CP-DOS TopView”, they said, “and we can talk some more about a CP-DOS Windows with our official blessing.”

Ever helpful, IBM referred Microsoft to six programmers in Berkeley, California, who called themselves Dynamical Systems Research, who had recently come to them with a portable re-implementation of TopView which was supposedly one-quarter the size and ran four to ten times faster. (That such efficiency gains over the original version were even possible confirmed every one of Microsoft’s prejudices against IBM’s programmers.) In June of 1986, Steve Ballmer duly bought a plane ticket for Berkeley, and two weeks later Microsoft bought Dynamical for $1.5 million. And then, a month after that event, IBM summoned Gates and Ballmer to their offices and told them that they had changed their minds; there would now be no need for a TopView interface in CP-DOS. IBM’s infuriating about-face seemingly meant that Microsoft had just thrown away $1.5 million. (Luckily for them, in the end they would get more than their money’s worth out of the programming expertise they purchased when they bought Dynamical, despite never doing anything with the alternative TopView technology; more on that in a future article.)

The one good aspect of this infuriating news was that IBM had at last decided that they and Microsoft should write a proper GUI for CP-DOS. Even this news wasn’t, however, as good as Microsoft could have wished: said GUI wasn’t to be Windows, but rather a new environment known as the Presentation Manager, which was in turn to be a guinea pig for a new bureaucratic monstrosity known as the Systems Application Architecture. SAA had been born of the way that IBM had diversified since the time when the big System/360 mainframes had been by far the most important part of their business. They still had those hulking monsters, but they had their personal computers now as well, along with plenty of machines in between the two extremes, such as the popular System/38 range of minicomputers. All of these machines had radically different operating systems and operating paradigms, such that one would never guess that they all came from the same company. This, IBM had decided, was a real problem in terms of technological efficiency and marketing alike, one which only SAA could remedy. They described the latter as “a set of software interfaces, conventions, and protocols — a framework for productively designing and developing applications with cross-system dependency.” Implemented across IBM’s whole range of computers, it would let programmers transition easily from one platform to another thanks to a consistent API, and the software produced with it would all have a consistent, distinctively “IBM” look and feel, conforming to a set-in-stone group of interface guidelines called Common User Access.

SAA and CUA might seem a visionary scheme from the vantage point of our own era of widespread interoperability among computing platforms. In 1986, however, the devil was very much in the details. The machines which SAA and CUA covered were so radically different in terms of technology and user expectations that a one-size-fits-all model couldn’t possibly be made to seem anything but hopelessly compromised on any single one of them. CUA in particular was a pedant’s wet dream, full of stuff like a requirement that every single dialog box had to have buttons which said “OK = Enter” and “ESC = Cancel,” instead of just “OK” and “Cancel.” “Surely we can expect people to figure that out without beating them over the head with it every single time!” begged Microsoft.

For a time, such pleas fell on deaf ears. Then, as more and more elements descended from IBM’s big computers proved clearly, obviously confusing in the personal-computing paradigm, Microsoft got permission to replace them with elements drawn from their own Windows. The thing just kept on getting messier and messier, a hopeless mishmash of two design philosophies. “In general, Windows and Presentation Manager are very similar,” noted one programmer. “They only differ in every single application detail.” The combination of superficial similarity with granular dissimilarity could only prove infuriating to users who went in with the reasonable expectation that one Microsoft-branded GUI ought to work pretty much the same as another.

Yet the bureaucratic boondoggle that was SAA and CUA wasn’t even the biggest bone of contention between IBM and Microsoft. That rather took the form of one of the most basic issues of all: what CPU the new operating system should target. Everyone agreed that the old 8088 should be left in the past along with the 640 K barrier it had spawned, but from there opinions diverged. IBM wanted to target the 80286, thus finally providing all those PC/ATs they had already sold with an operating system worthy of their hardware. Microsoft, on the other hand, wanted to skip the 80286 and target Intel’s very latest and greatest chip, the 80386.

The real source of the dispute was that same old wellspring of pain for anyone hoping to improve upon MS-DOS: the need to make sure that the new-and-improved operating system could run old MS-DOS software. Doing so, Bill Gates pointed out, would be far more complicated from the programmer’s perspective and far less satisfactory from the user’s perspective with the 80286 than it would with the 80386. To understand why, we need to look briefly at the historical and technical circumstances behind each of the chips.

It generally takes a new microprocessor some time to go from being available for purchase on its own to being integrated into a commercial computer. Thus the 80286, which first reached the mass market with the PC/AT in August of 1984, first reached Intel’s product catalog in February of 1982. It had largely been designed, in other words, before the computing ecosystem spawned by the IBM PC existed. Its designers had understood that compatibility with the 8088 might be a good thing to have to go along with the capabilities of the chip’s new protected mode, but had seen the two things as an either/or proposition. You would either boot the machine in real mode to run a legacy 8088-friendly operating system and its associated software, or you’d boot it in protected mode to run a more advanced operating system. Switching between the two modes required resetting the chip — a rather slow process that Intel had anticipated happening only when the whole machine in which it lived was rebooted. The usage scenario which Intel had most obviously never envisioned was the very one which IBM and Microsoft were now proposing for CP-DOS: an operating system that constantly switched on the fly between protected mode, which would be used for running the operating system itself and native applications written for it, and real mode, which would be used for running MS-DOS applications.

But the 80386, which entered Intel’s product catalog in September of 1985, was a very different beast, having had the chance to learn from the many Intel-based personal computers which had been sold by that time. Indeed, Intel had toured the industry before finalizing their plans for their latest chip, asking many of its movers and shakers — a group which prominently included Microsoft — what they wanted and needed from a third-generation CPU. The end result offered a 32-bit architecture to replace the 16 bits of the 80286, with the capacity to address up to 4 GB of memory in protected mode to replace the 16 MB address space of the older chip. But hidden underneath the obvious leap in performance were some more subtle features that were if anything even more welcome to programmers in Microsoft’s boat. For one thing, the new chip could be switched between real mode and protected mode quickly and easily, with no need for a reset. And for another, Intel added a third mode, a sort of compromise position in between real and protected mode that was perfect for addressing exactly the problems of MS-DOS compatibility with which CP-DOS was doomed to struggle. In the new “virtual” mode, the 80386 could fool software into believing it was running on an old 8088-based machine, including its own virtual 1 MB memory map, which the 80386 automatically translated into the real machine’s far more expansive memory map.

The power of the 80386 in comparison to the 8088 was such that a single physical 80386-based machine should be able to run a dozen or more virtual MS-DOS machines in parallel, should the need arise — all inside a more modern, sophisticated operating system like the planned CP-DOS. The 80386’s virtual mode really was perfect for Microsoft’s current needs — as it ought to have been, given that Microsoft themselves were largely responsible for its existence. It offered them a chance that doesn’t come along very often in software engineering: the chance to build a modern new operating system while maintaining seamless compatibility with the old one.

Some reports have it that Bill Gates, already aware that the 80386 was coming, had tried to convince IBM not to build the 80286-based PC/AT at all back in 1984, had told them they should just stay with the status quo until the 80386 was ready. But even in 1986, the 80386 according to IBM was just too far off in the future as a real force in personal computing to become the minimum requirement for CP-DOS. They anticipated taking a leisurely two-and-a-half years or so, as they had with the 80286, to package the 80386 into a new model. Said model thus likely wouldn’t appear until 1988, and its sales might not reach critical mass until a year or two after that. The 80386 was, IBM said, simply a bridge too far for an operating system they wanted to release by 1987. Besides, in light of the IBM Safeness Doctrine, they couldn’t just abandon those people who had already spent a lot of money on PC/ATs under the assumption that it was the IBM personal computer of the future.

“Screw the people with ATs,” was Gates’s undiplomatic response. “Let’s just make it for the 386, and they can upgrade.” He gnashed his teeth and raged, but IBM was implacable. Instead of being able to run multiple MS-DOS applications in parallel on CP-DOS, almost as if they had been designed for it from the start, Microsoft would be forced to fall back on using their new operating system as little more than a launcher for the old whenever the user wished to run an MS-DOS application. And it would, needless to say, be possible to run only one such application at a time. None of that really mattered, said IBM; once people saw how much better CP-DOS was, developers would port their MS-DOS applications over to it and the whole problem of compatibility would blow away like so much smoke. Bill Gates was far less sanguine that Microsoft and IBM could so easily kill their cockroach of an operating system. But in this as in all things, IBM’s decision was ultimately the law.

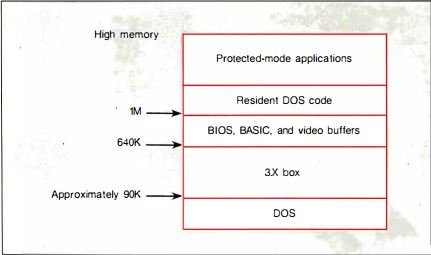

Here we see the CP-DOS (later OS/2 1.x) physical memory map. A single MS-DOS application can be loaded into the space below 1 MB — more specifically, into the box labeled “3.x” above. (MS-DOS 3 was the current version at the time that IBM and Microsoft were working on CP-DOS.) Because MS-DOS applications must run in the processor’s real mode, accessing physical rather than virtual memory addresses, only one application can be loaded into this space — and only this space! — at a time. Native CP-DOS applications live in the so-called “high memory” above the 1 MB boundary — more specifically, in the space labelled “protected-mode” in the diagram above. As many of these as the user wishes can be loaded at one time up there. Had IBM agreed to build CP-DOS for the 80386 rather than the 80286, it would have been possible to use that processor’s “virtual” mode to trick MS-DOS applications into believing they were running in real mode underneath the 640 K boundary, regardless of where they actually lived in memory. This would have allowed the user to run multiple MS-DOS applications alongside multiple native CP-DOS applications. In addition, an 80386 CP-DOS would have been able to address up to 4 GB of memory rather than being limited to 16 MB.

Microsoft’s frustration only grew when IBM’s stately timetable for the 80386 was jumped by the increasingly self-confident clone makers. In September of 1986, Compaq, the most successful and respected clone maker of all, shipped the DeskPro 386, the very first MS-DOS-compatible machine to use the chip. Before the end of the year, several other clone makers had announced 80386-based models of their own in response. It was a watershed moment in the slow transformation of business-oriented microcomputing from an ecosystem where IBM blazed the trails and a group of clone makers copied their innovations to one where many equal players all competed and innovated within an established standard for software and hardware which existed independently of all of them. A swaggering Compaq challenged IBM to match the DeskPro 386 within six months “or be supplanted as the market’s standard-setter.” Michael Swarely, Compaq’s marketing guru, was already re-framing the conversation in ways whose full import would only gradually become clear over the years to come:

We believe that an industry standard that has been established for software for the business marketplace is clearly in place. What we’ve done with the DeskPro 386 is innovate within that existing standard, as opposed to trying to go outside the standard and do something different. IBM may or may not enter the [80386] marketplace at some point in the future. The market will judge what IBM brings in the same way that it judges any other manufacturer’s new products. They have to live within the market’s realities. And the reality is that American business has made an enormous investment in an industry standard.

More than ever before, IBM was feeling real pressure from the clone makers. Their response would give the lie to all of their earlier talk of an open architecture and their commitment thereto.

IBM had already been planning a whole new range of machines for 1987, to be called the PS/2 line. Those plans had originally not included an 80386-based machine, but one was hastily added to the lineup now. Yet the appearance of that machine was only one of the ways in which the PS/2 line showed plainly that clone makers like Compaq were making IBM nervous with their talk of a “standard” that now had an existence independent from the company that had spawned it. IBM planned to introduce with the PS/2 line a new type of system bus for hardware add-ons, known as the Micro Channel Architecture. Whatever its technical merits, which could and soon would be hotly debated, MCA was clearly designed to cut the clone makers off at the knees. Breaking with precedent, IBM wrapped MCA up tight inside a legal labyrinth of patents, meaning that anyone wishing to make a PS/2 clone or even just an MCA-compatible expansion card would have to negotiate a license and pay for the privilege. If IBM got their way, the curiously idealistic open architecture of the original IBM PC would soon be no more.

In a testimony to how guarded the relationship between the two supposed fast partners really was, IBM didn’t even tell Microsoft about their plans for the PS/2 line until just a few months before the public announcement. Joint Development Agreement or no, the former now suspected the latter’s loyalty more strongly than ever — and for, it must be admitted, pretty good reason: a smiling Bill Gates had recently appeared alongside two executives from Compaq and their DeskPro 386 on the front page of InfoWorld. Clearly he was still playing both sides of the fence.

Now, Bill Gates got the news that CP-DOS was to be renamed OS/2, and would join PS/2 as the software half of a business-microcomputing future that would once again revolve entirely around IBM. For some time, he wasn’t even able to get a clear answer to the question of whether IBM intended to allow OS/2 to run at all on non-PS/2 hardware — whether they intended to abandon their old PC/AT customers after all, writing them off as collateral damage in their war against the clonesters and making MCA along with an 80286 a minimum requirement of OS/2.

On April 2, 1987, IBM officially announced the PS/2 hardware line and the OS/2 operating system, sending shock waves through their industry. Would this day mark the beginning of the end of the clone makers?

Any among that scrappy bunch who happened to be observing closely might have been reassured by some clear evidence that this was a far more jittery version of IBM than anyone had ever seen before, as exemplified by the splashy but rather chaotic rollout schedule for the new world order. Three PS/2 machines were to ship immediately: one of them based around an Intel 8086 chip very similar to the 8088 in the original IBM PC, the other two based around the 80286. But the 80386-based machine they were scrambling to get together in response to the Compaq DeskPro 386 — not that IBM phrased things in those terms! — wouldn’t come out until the summer. Meanwhile OS/2, which was still far from complete, likely wouldn’t appear until 1988. It was a far cry from the unified, confident rollout of the System/360 mainframe line more than two decades earlier, the seismic computing event IBM now seemed to be consciously trying to duplicate with their PS/2 line. As it was, the 80286- and 80386-based PS/2 machines would be left in the same boat as the older PC/AT for months to come, hobbled by that monument to inadequacy that was MS-DOS. And even once OS/2 did come out, the 80386-based PS/2 Model 80 would still remain somewhat crippled for the foreseeable future by IBM’s insistence that OS/2 run on the 80286 as well.

The first copies of the newly rechristened OS/2 to leave IBM and Microsoft’s offices did so on May 29, 1987, when selected developers who had paid $3000 for the privilege saw a three-foot long, thirty-pound box labelled “OS/2 Software Development Kit,” containing nine disks and an astonishing 3100 pages worth of documentation, thump onto their porch two months before Microsoft had told them it would arrive. As such, it was the first Microsoft product ever to ship early; less positively, it was also the first time they had ever asked anyone to pay to be beta testers. Microsoft, it seemed, was feeling their oats as IBM’s equal partners.

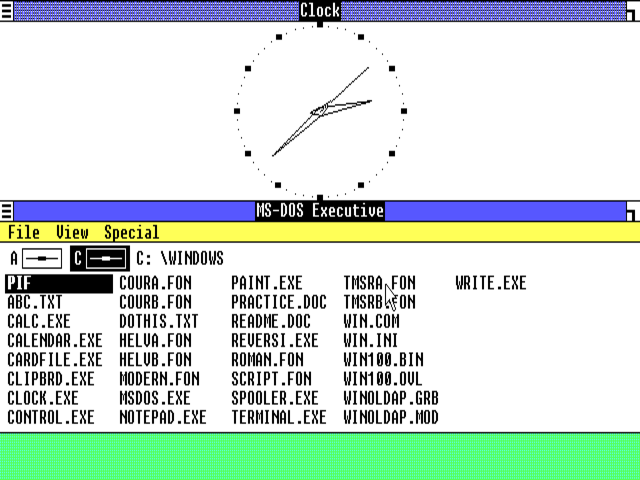

The first retail release of OS/2 also beat its announced date, shipping in December of 1987 instead of the first quarter of 1988. Thankfully, IBM listened to Microsoft’s advice enough to quell the very worst of their instincts: they allowed OS/2 to run on any 80286-or-better machine, not restricting it to the PS/2 line. Yet, at least from the ordinary user’s perspective, OS/2 1.0 was a weirdly underwhelming experience after all the hype of the previous spring. The Presentation Manager, OS/2’s planned GUI, had fallen so far behind amidst all the bureaucratic squabbling that IBM had finally elected to ship the first version of their new operating system without it; this was the main reason they had been able to release the remaining pieces earlier than planned. In the absence of the Presentation Manager, what the user got was the plumbing of a sophisticated modern operating system coupled to a command-line interface that made it seem all but identical to hoary old MS-DOS. I’ve already described in earlier articles how a GUI fits naturally with advanced features like multitasking and inter-application data sharing. These and the many other non-surface improvements which MS-DOS so sorely needed were there in OS/2, hidden away, but in the absence of a GUI only the programmer or the true power user could make much use of them. The rest of the world was left to ask why they had just paid $200 for a slightly less compatible, slightly slower version of the MS-DOS that had come free with their computers. IBM themselves didn’t quite seem to know why they were releasing OS/2 now, in this state. “No one will really use OS/2 1.0,” said Bill Lowe. “I view it as a tool for large-account customers or software developers who want to begin writing OS/2 applications.” With a sales pitch like that, who could resist? Just about everybody, as it happened.

OS/2 1.1, the first version to include the Presentation Manager — i.e., the first real version of the operating system in the eyes of most people — didn’t ship until the rather astonishingly late date of October 31, 1988. After such a long wait, the press coverage was lukewarm and anticlimactic. The GUI worked well enough, wrote the reviewers, but the whole package was certainly memory-hungry; the minimum requirement for running OS/2 was 2.5 MB, the recommended amount 5 MB or more, both huge numbers for an everyday desktop computer circa 1988. Meanwhile a lack of drivers for even many of the most common printers and other peripherals rendered them useless. And OS/2 application software as well was largely nonexistent. The chicken-or-the-egg-conundrum had struck again. With so little software or driver support, no one was in a hurry to upgrade to OS/2, and with so little user uptake, developers weren’t in a hurry to deliver software for it. “The broad market will turn its back on OS/2,” predicted Jeffrey Tarter, expressing the emerging conventional wisdom in the widely read insider newsletter Softletter. Philippe Kahn of Borland, an executive who was never at a loss for words, started a meme when he dubbed the new operating system “BS/2.” In the last two months of 1988, 4 percent of 80286 owners and 16 percent of 80386 owners took the OS/2 plunge. Yet even those middling figures gave a rosier view of OS/2’s prospects than was perhaps warranted. By 1990, OS/2 would still account for just 1 percent of the total installed base of personal-computer operating systems in the United States, while the unkillable MS-DOS still owned a 66-percent share.

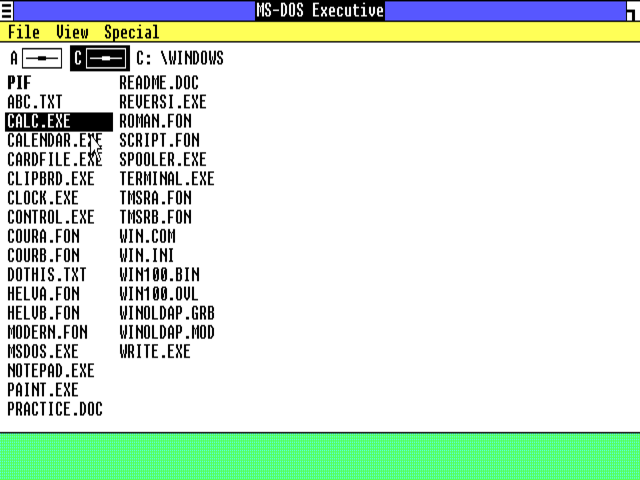

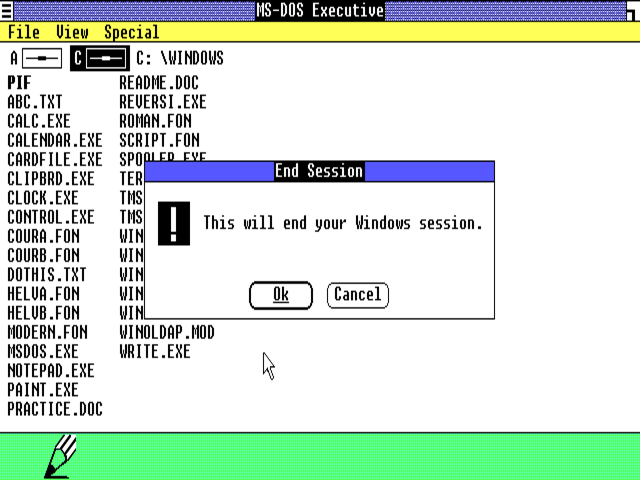

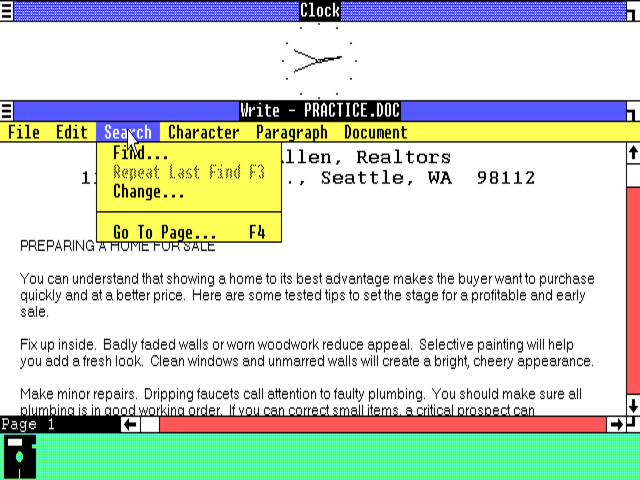

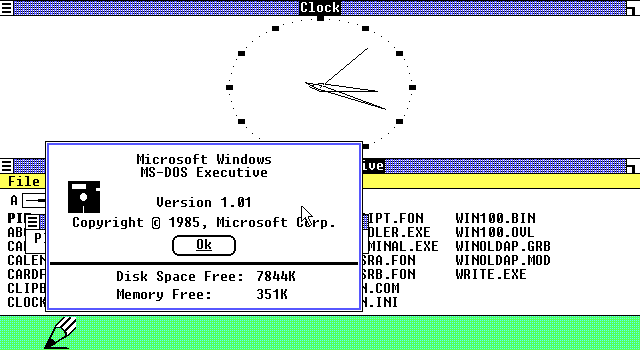

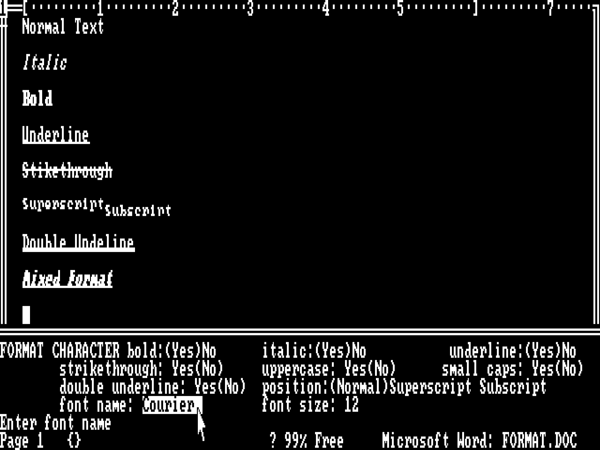

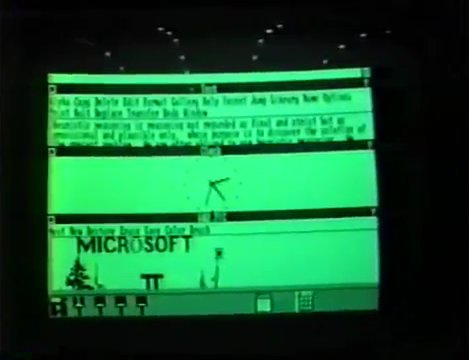

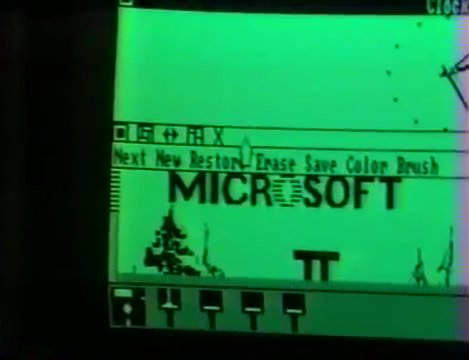

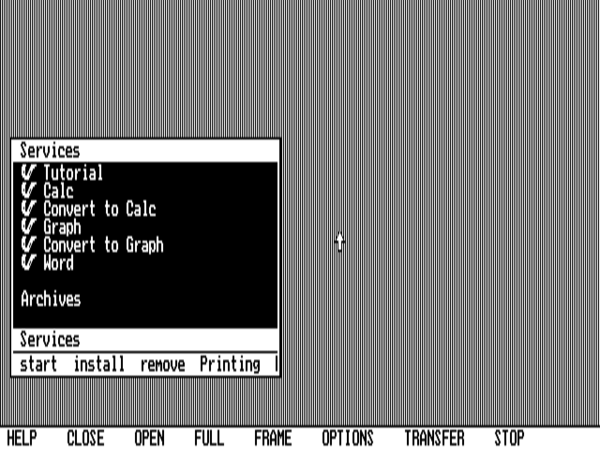

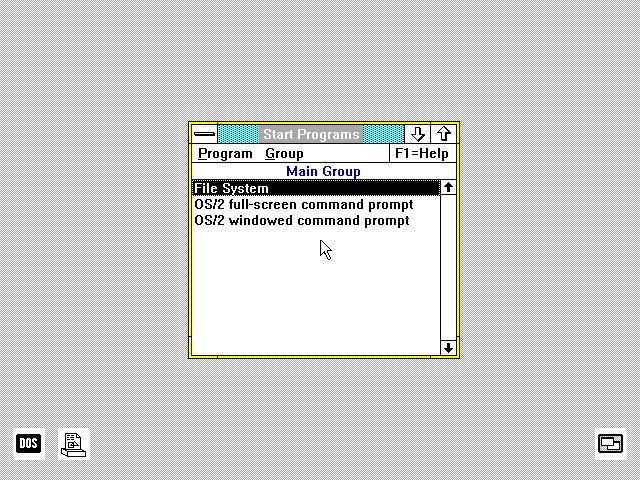

A Quick Tour of the OS/2 1.1 Presentation Manager

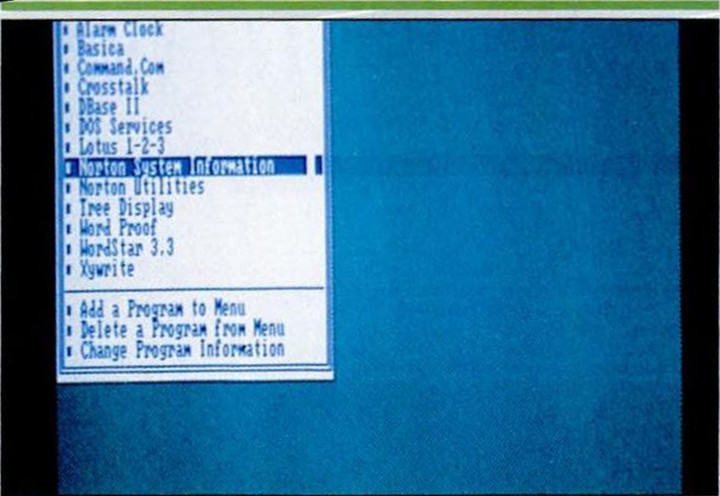

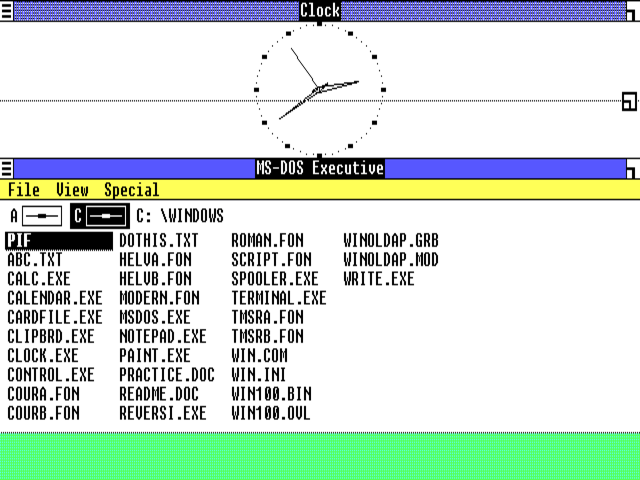

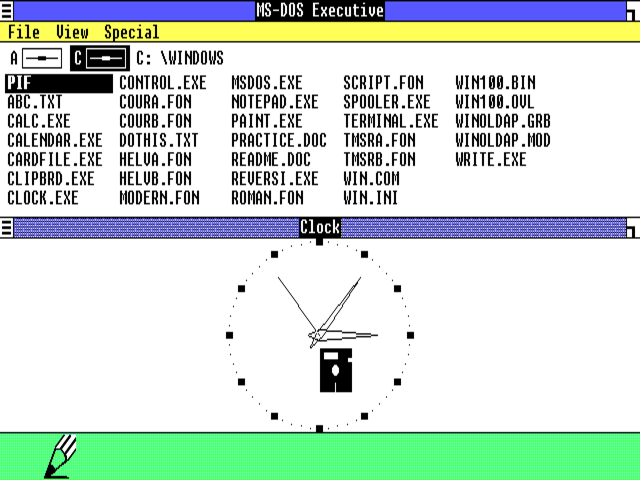

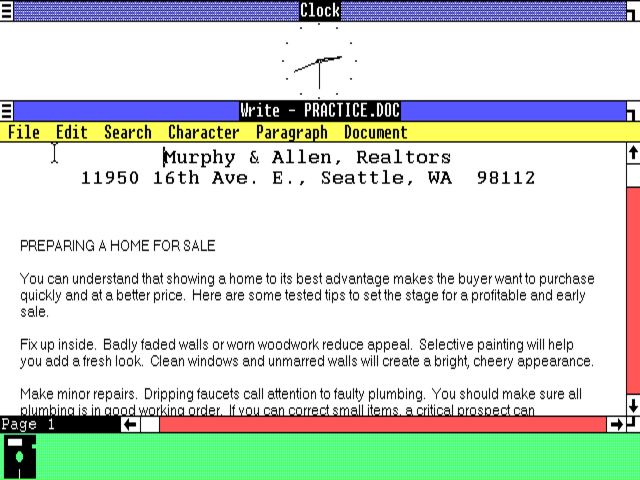

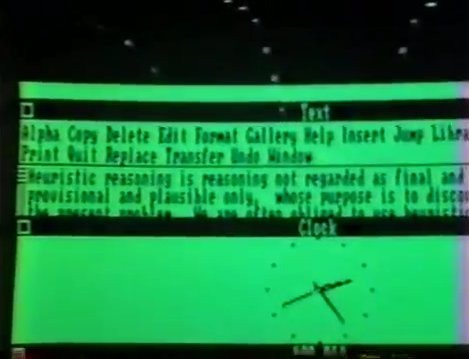

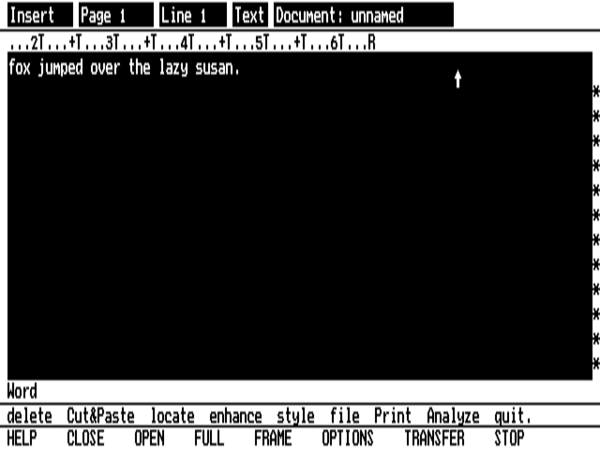

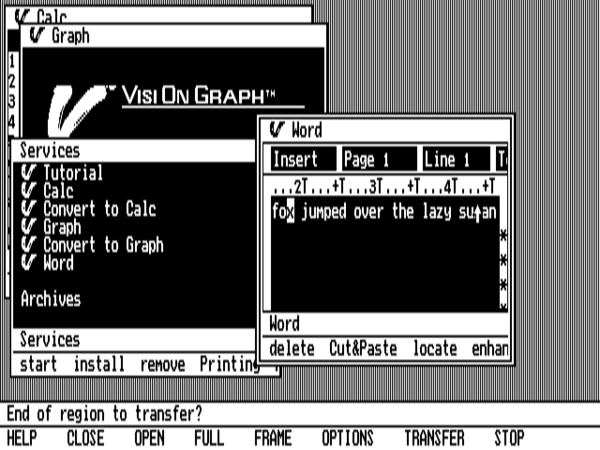

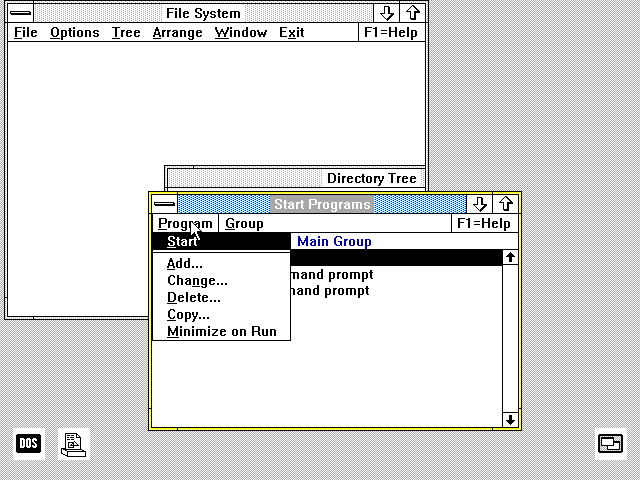

Presentation Manager boots into its version of a start menu, listing its installed programs. This fact of course means that, unlike Windows 1, Presentation Manager does include the concept of installing applications rather than just working with them at the file level. That said, it still remains much more text-oriented than modern versions of Windows or contemporary versions of MacOS. Applications are presented in the menu as a textual list, unaccompanied by icons. Only minimized applications and certain always-running utilities appear as icons on the “desktop,” which is still not utilized as the general-purpose workspace we’re familiar with today.

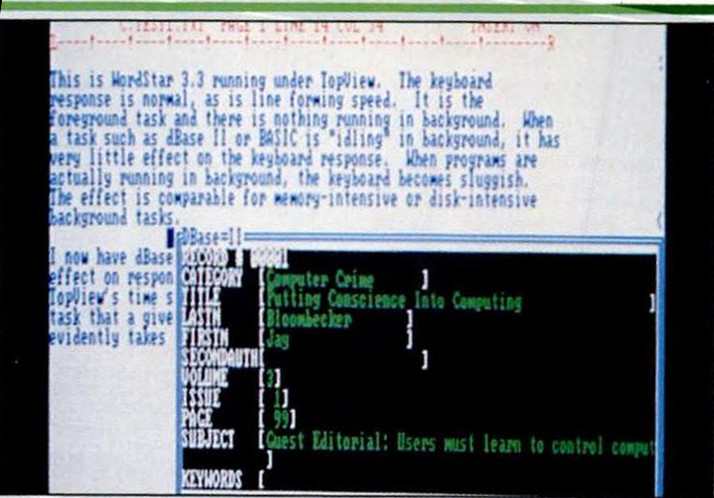

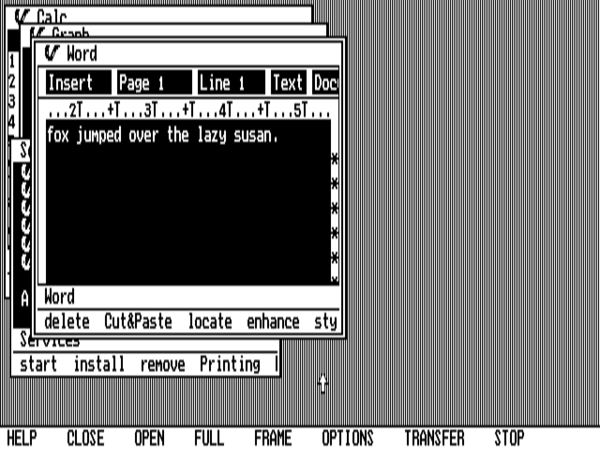

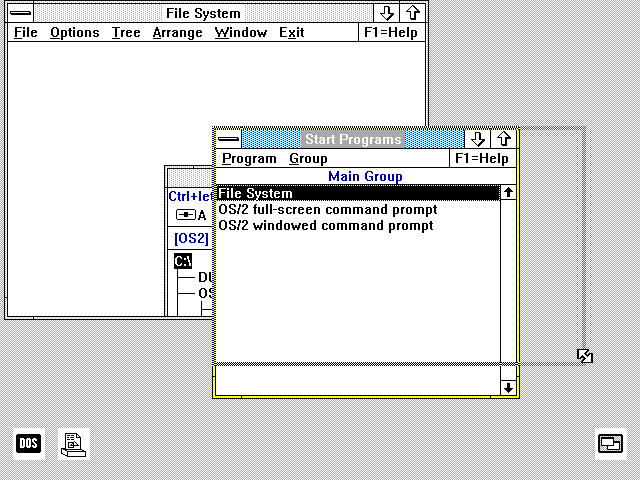

Still, in many ways Presentation Manager 1.1 feels vastly more intuitive today than Windows 1. The “tiled windows” paradigm is blessedly gone. Windows can be dragged freely around the screen and can overlay one another, and niceties like the sizing widgets all work as we expect them to.

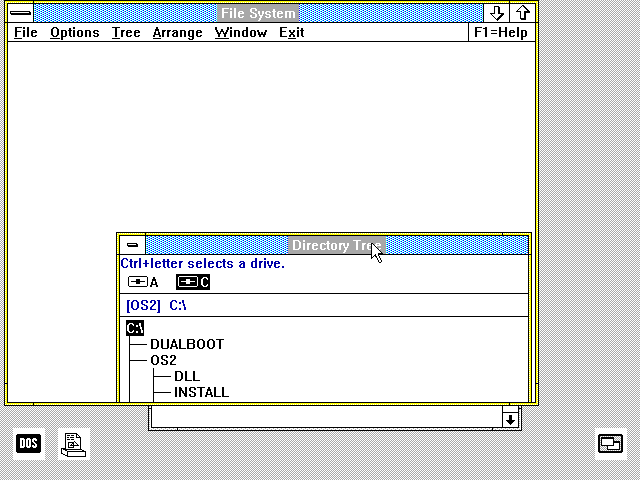

Applications can even open sub-windows that live within other windows. You can see one of these inside the file manager above.

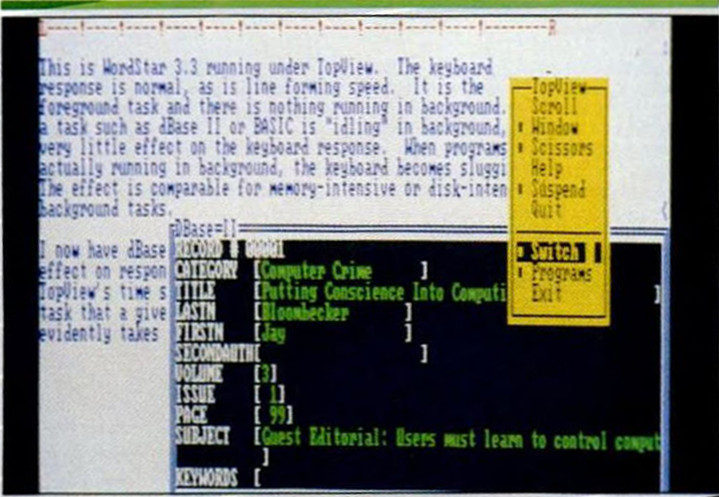

One area where Presentation Manager is less like the Macintosh than Windows 1, but more like current versions of Microsoft Windows, is in its handling of menus. The one-click menu approach is used here, not the click-and-hold approach of the Mac.

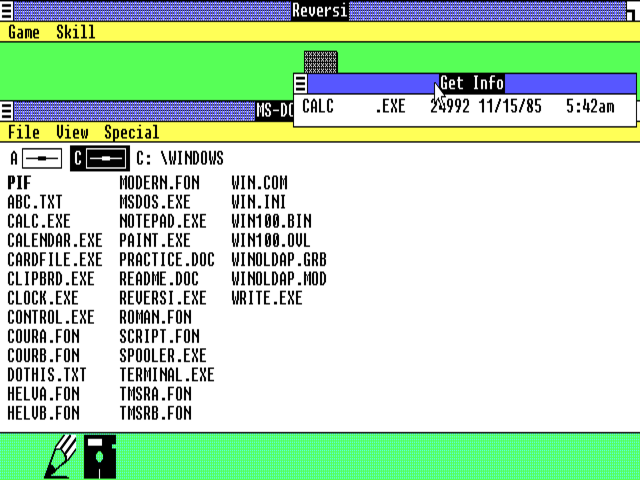

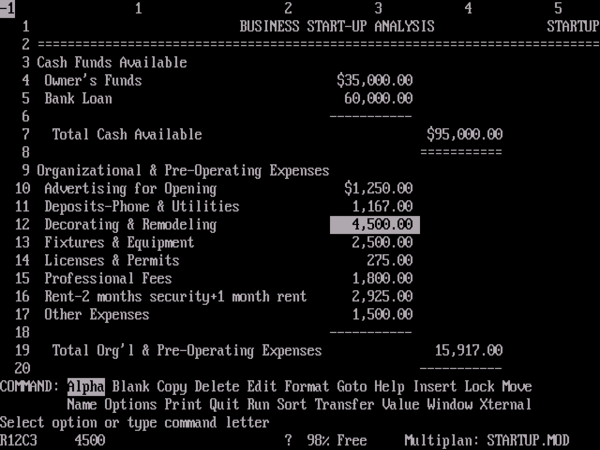

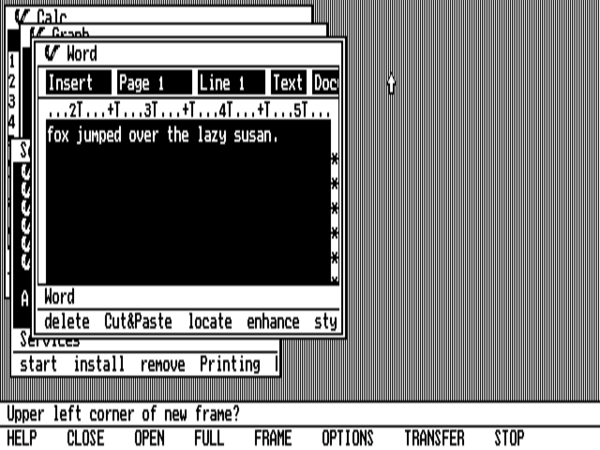

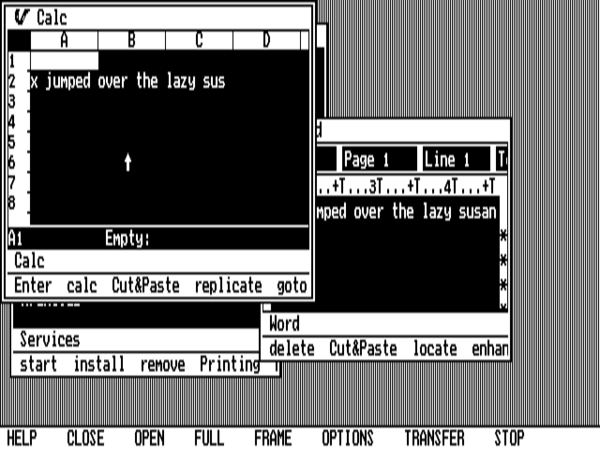

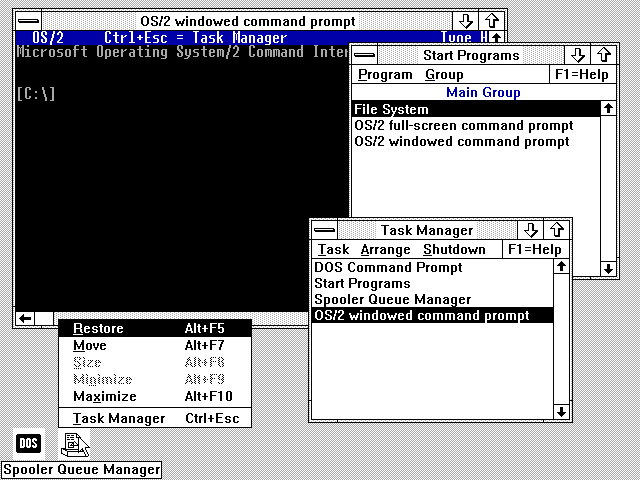

Here we’ve opened a DOS box for running vanilla MS-DOS software. Only one such application can be run at a time, thanks to IBM’s insistence that OS/2 should run on the 80286 processor.

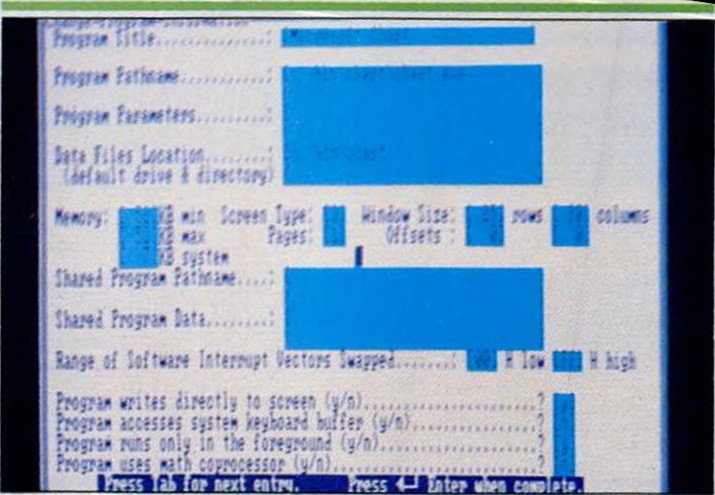

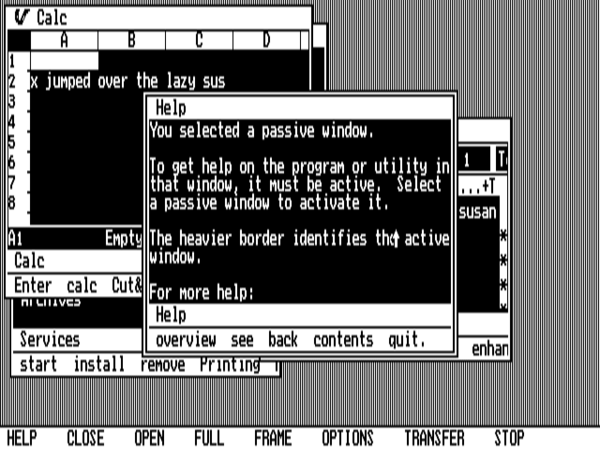

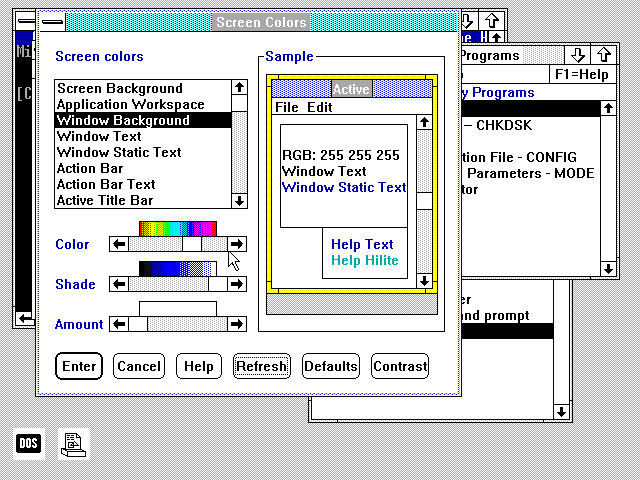

Presentation Manager includes a control panel for managing preferences that’s far slicker than the one included in Windows 1. Yet it shipped with a dearth of the useful little applets Microsoft included with Windows right from the beginning. There isn’t so much as a decent text editor here. Given that IBM would struggle mightily to get third-party developers to write applications for OS/2, such stinginess was… not good.

Amidst all of the hoopla over the introduction of the PS/2 and OS/2 back in the spring of 1987, Byte‘s editor-in-chief Philip Lemmons had sounded a cautionary note to IBM that reads as prescient today:

With the introduction of the PS/2 machines, IBM has begun to compete in the personal-computer arena on the basis of technology. This development is welcome because the previous limitations of the de-facto IBM standard were painfully obvious, especially in systems software. The new PS/2 “standard” offers numerous improvements: the Micro Channel is a better bus than the PC and AT buses, and it provides a full standard for 32-bit buses. The VGA graphics standard improves on EGA. The IBM monitors for the PS/2 series take a new approach that will ultimately deliver superior performance at lower prices. IBM is using 3.5-inch floppy disks that offer more convenience, capacity, and reliability than 5.25-inch floppy disks. And OS/2, the new system software jointly developed by Microsoft and IBM, will offer advances such as true multitasking and a graphic user interface.

Yet a cloud hangs over all this outstanding new technology. Like other companies that have invested in the development of new technology, IBM is asserting proprietary rights in its work. When most companies do this in most product areas, we expect and accept it. When one company has a special role of setting the de-facto standard, however, the aggressive assertion of proprietary rights prevents the widespread adoption of the new standard and delays the broad distribution of new technology.

The personal-computer industry has waited for years for IBM to advance the standard, and now, depending on IBM’s moves, may be unable to participate in that advancement. If so, the rest of the industry and the broad population of computer users still need another standard for which to build and buy products — a standard at least as good as the one embodied in the PS/2 series.

Lemmons’s cautions were wise ones; his only mistake was in not stating his concerns even more forcefully. For the verdict of history is clear: PS/2 and OS/2 are the twin disasters which mark the end of the era of IBM’s total domination of business-oriented microcomputing. The PS/2 line brought with it a whole range of new hardware standards, some of which, like new mouse and keyboard ports and a new graphics standard known as VGA, would remain with us for decades to come. But these would mark the very last technical legacies of IBM’s role as the prime mover in mainstream microcomputing. Other parts of the PS/2 line, most notably the much-feared proprietary MCA bus, did more to point out the limits of IBM’s power than the opposite. Instead of dutifully going out of business or queuing up to buy licenses, third-party hardware makers simply ignored MCA. They would eventually form committees to negotiate new, open bus architectures of their own — just as Philip Lemmons predicts in the extract above.

OS/2 as well only served to separate IBM’s fate from that of the computing standard they had birthed. It arrived late and bloated, and went largely ignored by users who stuck with MS-DOS — an operating system that was now coming to be seen not as IBM’s system-software standard but as Microsoft’s. IBM’s bold bid to cement their grip on the computer industry only caused it to slip through their fingers.

All of which placed Microsoft in the decidedly strange position of becoming the prime beneficiary of the downfall of an operating system which they had done well over half the work of creating. Given the way that Bill Gates’s reputation as the computer industry’s foremost Machiavelli precedes him, some have claimed that he planned it all this way from the beginning. In their otherwise sober-minded book Computer Wars: The Fall of IBM and the Future of Global Technology, Charles H. Ferguson and Charles R. Morris indulge in some elaborate conspiracy theorizing that’s all too typical of the whole Gates-as-Evil-Genius genre. Gates made certain that his programmers wrote OS/2 in 80286 assembly language rather than a higher-level language, the authors claim, to make sure that IBM couldn’t easily adapt it to take advantage of the more advanced capabilities of chips like the 80386 after his long-planned split with them finally occurred. In the meantime, Microsoft could use the OS/2 project to experiment with operating-system design on IBM’s dime, paving the way for their own eventual MS-DOS replacement.

If Gates expected ultimately to break with IBM, he has every interest in ensuring OS/2’s failure. In that light, tying the project tightly to 286 assembler was a masterstroke. Microsoft would have acquired three years’ worth of experience writing an advanced, very sophisticated operating system at IBM’s elbow, applying all the latest development tools. After the divorce, IBM would still own OS/2. But since it was written in 286 assembler, it would be almost utterly useless.

In reality, the sheer amount of effort Microsoft put into making OS/2 work over a period of several years — far more effort than they put into their own Windows over much of this period — argues against such conspiracy-mongering. Bill Gates was unquestionably trying to keep one foot in IBM’s camp and one foot in the clone makers’, much to the frustration of both, who equally craved his undivided loyalty. But he had no crystal ball, and he wasn’t playing three-dimensional chess. He was just responding, rather masterfully, to events on the ground as they happened, and always — always — hedging all of his bets.

So, even as OS/2 was getting all the press, Windows remained a going concern, Gates’s foremost hedge against the possibility that the vaunted new operating system might indeed prove a failure and MS-DOS might remain the standard it had always been. “Microsoft has a religious approach to the graphical user interface,” said the GUI-skeptic Pete Peterson, vice president of WordPerfect Corporation, around this time. “If Microsoft could choose between improved earnings and growth and bringing the graphical user interface to the world, they’d choose the graphical user interface.” In his own way, Peterson was misreading Gates as badly here as the more overheated conspiracy theorists have tended to do. Gates was never one to sacrifice profits to any ideal. It was just that he saw the GUI itself — somebody’s GUI — as such an inevitability. And thus he was determined to ensure that the inevitability had a Microsoft logo on the box when it became an actuality. If the breakthrough product wasn’t to be the OS/2 Presentation Manager, it would just have to be Microsoft Windows.

(Sources: the books The Making of Microsoft: How Bill Gates and His Team Created the World’s Most Successful Software Company by Daniel Ichbiah and Susan L. Knepper, Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire by James Wallace and Jim Erickson, Gates: How Microsoft’s Mogul Reinvented an Industry and Made Himself the Richest Man in America by Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, and Computer Wars: The Fall of IBM and the Future of Global Technology by Charles H. Ferguson and Charles R. Morris; InfoWorld of October 7 1985, July 7 1986, August 12 1991, and October 21 1991; PC Magazine of November 12 1985, April 12 1988, December 27 1988, and September 12 1989; New York Times of August 22 1985; Byte of June 1987, September 1987, October 1987, April 1988, and the special issue of Fall 1987; the episode of the Computer Chronicles television program called “Intel 386 — The Fast Lane.” Finally, I owe a lot to Nathan Lineback for the histories, insights, comparisons, and images found at his wonderful online “GUI Gallery.”)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Admittedly, this was already beginning to change as IBM was having this debate: the X Window project was born at MIT in 1984. |

|---|