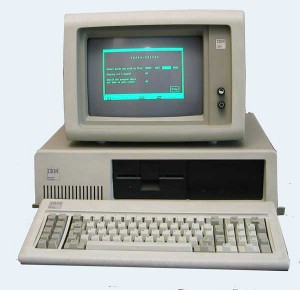

IBM’s greatest triumph was inextricably linked with what by 1986 was turning into their biggest problem. Following its introduction five years before, the IBM PC had remade the face of corporate computing in its image, legitimizing personal computing in the eyes of the Fortune 500 and all those smaller companies who dreamed of someday joining their ranks. The ecosystem that surrounded the IBM PC and its successors was now worth countless billions, the greatest story of American business success of them all to play out during Ronald Reagan’s storied Morning in America.

The problem, at least as IBM and many of their worried stockholders perceived it, was that they now seemed on the verge of losing control of the very standard they had created. A combination of the decisions that had allowed the original IBM PC to become a standard in the first place — its simple, workmanlike design that utilized only off-the-shelf components; the scrupulously thorough documentation of said design; the decision to outsource the machine’s operating system to Microsoft, a third party all too willing to license the same operating system to other parties as well — had led to a thriving market in so-called “clone” machines whose combined revenues now far exceeded IBM’s personal-computer sales. IBM believed that the clonesters were lifting billions out of their pockets every year, even as they saw their own sales, which had broken record after record in the first few years following the IBM PC’s launch, beginning to show signs of stagnation.

Compaq of Houston, Texas, the most aggressive and innovative of the clonesters, had first begun to collect for themselves a reputation to rival IBM’s own with their very first product back in 1983, a portable — or, perhaps better said, “luggable” — all-in-one IBM-compatible. The Compaq Portable had forced IBM for the first time to play catch-up with a personal-computing rival, rushing to market a luggable of their own. To make matters worse, the IBM version of portable computing had proved far less practical than the Compaq, as many a reviewer wasn’t shy about pointing out.

Now, in 1986, Compaq threatened to wrangle away from IBM the mantle of technological leadership via a machine that represented a more fundamental advance than a new form factor. After hearing that IBM didn’t have any immediate plans to release a machine built around the Intel 80386, a new 32-bit processor that was sending waves of excitement rippling through the industry, Compaq decided to push ahead with a 386-based machine of their own — right now, this very year. The public launch of the Compaq Deskpro 386 on September 9, 1986 — almost exactly five years after the debut of the original IBM PC — was another watershed moment, the first time one of the clonesters had released a machine more powerful than anything in IBM’s stable. Compaq’s CEO Rod Canion, never a shrinking violet under any circumstances, outdid himself at the launch, declaring the Deskpro 386 “the third generation of the personal-computer revolution” after the Apple II and the IBM PC, thus implicitly placing his own Compaq on a par with those two storied companies.

The clone market was getting so big that there seemed a danger that the clones wouldn’t be dismissed under that selfsame moniker much longer. People in the business world were beginning to replace the phrase “IBM clone” with phrases like “the MS-DOS standard” or “the Intel standard,” giving no credit to the company that had really created that standard. As was well attested by their checkered history of antitrust investigations and allegations of unfair competitive practices, IBM had never been known as a bastion of corporate generosity. It may not be exaggerating the case to say that they felt themselves to have a moral right to the PC standard they’d created, a right that encompassed not just an acknowledgement that said standard was still the IBM standard but also the ability to continue to steer every aspect of the further development of that standard. And by all rights the right should also encompass — and this was the sticking point that really irked — their fair share of all those billions that all those other companies were making from IBM’s standard.

In addition to furnishing what they saw as ample evidence of a need for them to reassert control of their industry, this period found IBM at another, more purely technical crossroads. The imminent move from 16-bit to 32-bit computing represented by the new 80386 would have to bring with it some elaborations on IBM’s tried-and-true architecture — elaborations that would undoubtedly define the face of mainstream business computing into the 1990s. IBM saw in those elaborations a way to remedy the ongoing problem of the clonesters as well. Unknown to everyone outside the company, they were about to initiate the so-called “bus wars,” a premeditated strike aimed directly at what they saw as parasites like Compaq.

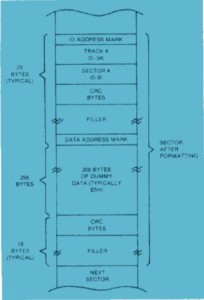

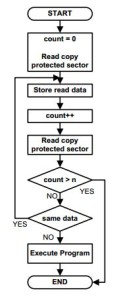

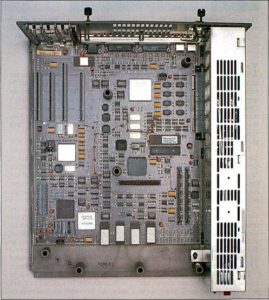

The bus in this context referred not to a mode of public transportation but rather to the system of expansion slots that allowed the innermost core of an IBM-compatible computer — little more than the processor and memory — to communicate with just about everything else that made up a full-fledged PC: floppy and hard disk drives, monitors, modems, printers, ad infinitum, from the most generalized components found in just about every office to the most specialized for the most esoteric of tasks. The original IBM PC, built around a hybrid 8-bit and 16-bit chip called the Intel 8088, had used an 8-bit bus, meaning the electronic “channel” it used to talk to all these myriad devices was just 8 bits wide. In 1984, IBM had released the PC/AT, built around the newer fully 16-bit Intel 80286, and in that machine had expanded the original bus to support 16-bit devices while remaining backward compatible with the older 8-bit standard. The result retroactively came to be known as the Industry Standard Architecture, or ISA.

Now, with the 32-bit 80386 a reality, it was time to think about revisiting the bus again, to make it support 32-bit communications. To fail to do so would be to cripple the 386, forcing it to act like a 16-bit chip every time it wanted to communicate with a peripheral; impressive as they were in many ways, the Compaq Deskpro 386 and other early 386 clones saw their performance limited by exactly this problem. Most people expected IBM to do for the 386 what they had previously done for the 286, delivering a new bus which would support 32-bit peripherals but remain compatible with older 16-bit and even 8-bit devices. Instead they delivered something they called the Micro Channel Architecture, or MCA, a complete break with the past which supported only 32-bit peripherals.

So much controversy over something barely noticeable. The four Micro Channel slots sit at the left rear of this PS/2 Model 50. Many of the components that would have been housed in expansion cards in earlier IBM systems, such as the video card and hard-drive controller, were moved onto the motherboard with the PS/2 line.

MCA debuted as a key component in a new line of personal computers in April of 1987, the most ambitious such IBM had ever or would ever introduce. The Personal System/2 lineup — better known as the PS/2 — was envisioned as exactly the next generation in personal computing that an ebullient Rod Canion had perhaps overenthusiastically declared the Compaq Deskpro 386 to represent barely six months before. IBM was determined to once again remake the computer industry in their image — and to get it right this time, avoiding the perceived mistakes that had led to the rise of the clonesters. The PS/2 lineup did encompass lower-end machines using the old 16-bit PC/AT bus, but the real point of the effort lay with the higher-end models, IBM’s first to use the 80386 and their first to use the new MCA bus architecture to take advantage of all of the 32 bits of throughput offered by that chip. IBM offered various technical justifications for the failure of MCA to support their older bus standards, but they always rang false. As the more astute industry observers quickly realized, MCA had more to do with business and marketing than it did with technology in the abstract.

IBM was attempting a delicate trick with MCA. They wanted to be able to continue to reap the enormous benefits of the business-computing standard they had birthed, with its huge constellation of compatible software that by now even more so than IBM’s reputation made an MS-DOS machine the only kind to be seriously considered by the vast majority of corporate purchasing departments. At the same time, though, they wanted to cut off the oxygen to the clonesters who were also benefiting so conspicuously from that same universal acceptance, and to reassert their role as the ultimate authorities on the direction business computing would take in the future. They believed they could accomplish all of that, in the long term at least, by threading the needle of compatibility — keeping the 386-based PS/2 lineup software-compatible with the older machines while deliberately breaking the hardware compatibility so relied on by the clonesters. In doing so, they would take the hardware to a place the clonesters couldn’t follow, thus securing for themselves all those billions the clonesters had heretofore been stealing out of their pockets.

Unlike the original IBM bus architecture, MCA was locked up inside an ironclad cage of patents, making it legally uncloneable unless one could somehow negotiate a license to do so through IBM. The patents even extended to add-on cards and other peripherals that might be compatible with MCA, meaning that absolutely anyone who wanted to make a hardware add-on for an MCA machine would have to negotiate a license and pay for the privilege. The result should be not only a lucrative new revenue stream but also complete control of business computing’s further evolution. Yes, the clonesters would be able to survive for a few more years making machines using the older 16-bit bus architecture. In the longer term, however, as personal computing inevitably transitioned into a realm of 32 bits, they would survive purely at IBM’s whim, their fate predicated on IBM’s willingness to grant them a patent license for MCA and their own willingness to pay dearly for it.

The clonesters rightly and immediately saw MCA as nothing less than an existential threat, and were thrown into a tizzy trying to figure out how to respond to it. It was the ever-quotable Rod Canion who came up with the best line of attack, drawing an analogy between MCA and the recent soft-drink marketing disaster of New Coke. (What with Pepsi alumnus John Sculley in charge over at Apple, computers and soft drinks seemed to be running oddly in parallel during this era.) Clever, pithy, and blessedly non-technical, Canion’s comparison spread like wildfire through the business press, regurgitated ad nauseam by journalists who often had little to no idea what this MCA thing that it referenced actually was. IBM never quite managed to formulate a response that didn’t sound nefariously evasive.

With the “New Coke” meme setting the tone, just about everything about the PS/2 line turned into an unexpected uphill struggle for IBM. While plenty of early reviewers dutifully toed the line, doubtless mindful that if no one ever got fired for buying IBM no one was likely to get fired for giving them a positive review either, a surprising number of the reviews were distinctly lukewarm. The complaints started and often ended with the prices. Even the low-end 16-bit PS/2 models started at a suggested list price of $2295 without monitor, while the high-end models topped out at almost $7000. Insider reports had it that IBM was enjoying profit margins of 40 percent or more, leading to rampant speculation on what the cost of entry into business-friendly personal computing might become if they really should manage to stamp out the clonesters.

The high-end models in particular struck many as a pointless waste of money given that IBM didn’t have an operating system ready to take advantage of their capabilities. The machines were all still saddled with MS-DOS, clunky and archaic and barely worthy of the name “operating system” even in the terms of 1987. In one of the more striking examples of hardware running away from software in computing history, the higher-end models shipped with 1 MB of memory, but couldn’t actually use more than 640 K of it thanks to MS-DOS’s built-in limitations. IBM promised a new, next-generation operating system called OS/2 to unlock the real potential of these next-generation machines. But OS/2, a project they had once again chosen to turn over to Microsoft, was still an unknown number of months away, with the so-called “Presentation Manager” that would add to it a Macintosh-style GUI due yet further months after that. [1]The full story of OS/2 and the Presentation Manager and their relationship to Microsoft Windows and even Apple’s MacOS is a complex yet fascinating one, but also one best reserved for a future article where I can give it its proper due. And, as a final little bit of buyer discouragement, IBM planned to charge the people who had already spent many thousands on their PS/2 hardware another $800 or so for the privilege of using the eventual OS/2 to take advantage of it.

The PS/2 launch prompted constant comparisons with the original IBM PC launch of five and a half years before, and constantly came up wanting. IBM’s publicity campaign was lavish — as it ought to have been, given those profit margins — but unfocused and uninspired. Its centerpiece was a series of commercials involving much of the cast from M*A*S*H, playing their old sitcom characters inexplicably transported from the Korean War to a modern office. With M*A*S*H still a beloved cultural touchstone only a few years removed from its record-shattering final episode, the spots had plenty of sheer star power, but lacked even a modicum of the charm or creativity that had characterized the award-winning “Charlie Chaplin” advertisements for the original IBM PC.

Likewise, it was hard not to compare the unexpected spirit of openness that had suffused the 1981 IBM PC with the domination and control IBM so plainly intended to assert with the 1987 PS/2 launch. Apple’s iconic old “Big Brother” Macintosh advertisement, a soaring triumph of rhetoric over substance back in its day, would have fit much better to the PS/2 line than it had to the state of business computing back in 1984. Many chose to blame the change in tone on the loss of Don Estridge, the leader of the small team that had built the original IBM PC. An unusually charismatic personality and independent thinker for the famously conservative and bureaucratic IBM — enough so that he had been courted by Steve Jobs to fill the CEO role John Sculley ended up taking at Apple — Estridge had been killed in a plane crash in 1985. His stewardship over IBM’s microcomputer division had been succeeded by that of William Lowe, a much more traditional rank-and-file, buttoned-down IBM man. Whether due to this reason or some other, the shift in tone and direction from 1981 to 1987 was striking.

In the months following the PS/2 line’s release, the media narrative drifted from one of uncertain excitement to reports of the new machines’ disappointing reception in many quarters. IBM sold around 200,000 MCA-equipped PS/2s in the first six months, mostly to the biggest of big business; United Airlines alone, for example, bought 40,000 of them as part of a complete revamping of their reservations system. But far too many even within the Fortune 500 proved stubbornly, unexpectedly resistant to IBM’s unsubtle prodding to jump onto the PS/2 train. Many chose to invest in the clonesters’ cheaper 80386 offerings instead; the 16-bit bus used by those machines, while far from ideal from a purely technical standpoint, did at least have the advantage of compatibility with existing peripherals. Seventeen months after MCA’s debut, 66 percent of all business computers being sold each month were still using the old bus architecture, versus just 20 percent that used MCA. (The remainder was largely accounted for by the Macintosh.) Survey after survey reported IBM to be losing market share rather than gaining it since the arrival of the PS/2. By this point OS/2 and its “Presentation Manager” GUI were finally available, but, hampered by that high price tag, the new operating system’s uptake had also been limited at best.

And then, just when it seemed the news couldn’t get much worse for IBM, much of the industry went into unthinkable open revolt against their ongoing hegemony. On September 13, 1988, a group of the clonesters, driven as usual by Compaq and with the tacit support of Intel and Microsoft, announced the creation of a new 32-bit bus standard, to be called the Extended Industry Standard Architecture, or EISA. Unlike MCA, EISA would be compatible with older 16-bit and 8-bit peripherals. And it would manage to be so without performing notably worse than MCA, thus giving the lie to IBM’s claims that their decision to abandon bus compatibility had been motivated by technical rather than business concerns. The press promptly dubbed the budding consortium, which included virtually every manufacturer of IBM-compatible computers not named IBM, the “Gang of Nine” after the allegedly traitorous Gang of Four of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Machines using the new EISA bus entered production within a year.

This shot of an EISA card illustrates the unique two-layer connection devised by the Gang of Nine to extend the old ISA standard without requiring ridiculously long, unwieldy cards and sockets. The shorter pins correspond to the older 16-bit standard; the longer extend it to 32 bits.

In the end, EISA would prove of limited technical importance in the evolution of the Intel architecture. The new standard didn’t have much more luck than had MCA in establishing itself as the market’s default. Instead, by the time a 32-bit bus became a truly commonplace need among ordinary computer users, EISA and MCA alike were replaced by a still newer and better standard than either called the Peripheral Component Interconnect, or PCI. The bus wars of the late 1980s and very early 1990s can thus all too easily be seen as just another of the industry’s tempests in a teapot, an obscure squabble over technical esoterica of interest only to hardcore hackers.

Look a little harder at EISA, however, and we see a watershed moment in the history of the personal computer that dwarfs even the arrival of the Compaq Portable or the Deskpro 386. The Gang of Nine’s announcement brought with it a torrent of press coverage that for the first time openly questioned IBM’s continuing dominance of business-oriented computing. CNN’s Moneyline, the most-watched business report on cable television, dredged up Canion’s evergreen New Coke analogy yet again, going so far as to open its reports on the Gang of Nine’s announcement with a shot of soda bottles moving down a production line. IBM was “faced with overwhelming resistance to the flavor of ‘New Compute,'” declared the breathless report that followed; September 13, 1988, “was a day that left Big Blue looking black and blue.” An only slightly more sober Wall Street Journal article had it that the Gang of Nine “was joining forces in an audacious attempt to wrest away from IBM the power of setting the standard for how personal computers are designed, and they seem to have a chance of succeeding.” The article threw all its metaphors in a blender for the big conclusion: “For IBM, the Gang’s announcement yesterday is at best a dust storm of confusion, and, at worst, a dagger to the heart of its PC strategy.” When the Wall Street Journal threatens to turn against your big business, you know you have problems.

And, indeed, September 13, 1988, wound up representing everything the pundits and journalists said it might and more. Simply put, this was the instant that IBM finally and definitively lost control of the business-computing industry, the moment when the architecture they had created back in 1981 left the nest to go its own way. After this instant, no one would ever defer to IBM again. In January of 1989, Arlan Levitan, a columnist for the big consumer-computing magazine Compute! — like most such magazines, not particularly known for the boldness of its editorial stances — signaled the shifting conventional wisdom. His editors empowered him to launch a satirical broadside at IBM, the PS/2, MCA, and even all those who had bought into the hype, a group that very much included their own magazine.

During a Monday morning press breakfast hosted by IBM, over a thousand representatives of the computing press were shocked to hear newly hired Entry Systems Division president P.W. Herman declare that the firm’s PS/2 computer systems and its associated products were part of an elaborate psychological study undertaken at the behest of the National Institute of Mental Health. “I sure am glad the American people haven’t lost their sense of humor. It’s good to know that in these times everybody still appreciates a good joke.” According to Herman, the study was intended to quantify the limits of the operational parameters associated with Abraham Lincoln’s most famous aphorism. Said Herman, “I guess you really can’t fool all of the people all of the time. I’ll tell ya, though — the Micro Channel Architecture even had me going for a while.” All PS/2 owners will receive a letter signed by Herman and thanking them for their personal contribution toward furthering the present-day understanding of aberrant behavior. Corporate executives who committed their firms to IBM’s $800 OS/2 operating system will receive free remedial therapy in DOS reeducation centers. Those who took advantage of IBM’s trade-in policy, whereby users gave up their XTs or ATs for a PS/2, will receive their weight in PCjr computers. According to internal IBM sources, all costs associated with manufacturing and promoting PS/2s will cumulatively qualify as a tax-deductible research grant.

In terms of hardware if not software — Microsoft’s long, often damaging domination was just beginning in the latter realm — the industry was now a meritocracy, bound together only by a set of mutually if often only tacitly agreed-upon standards. That could only mean hard times for IBM, who were hardly used to competing on such a level playing field. In 1993, they posted a loss of a staggering $8 billion, the largest to that point in American business history, prompting a long, painful process of reinvention as a smaller, nimbler, dare I say it even humbler company. In 2004, in another watershed moment symbolic of many things, IBM stopped making PCs altogether, selling what was left of their personal-computer division to the Chinese computer manufacturer Lenovo in order to focus on consulting services.

The PS/2 story has rightfully gone down in business history as a classic tale of overweening arrogance that received its justified comeuppance. In attempting so aggressively to seize complete control of business computing — all of it — IBM pissed away the enviable dominance they already enjoyed. In attempting to build an empire that stood utterly alone and unchallenged, they burned the one they already had.

Yet there is another side to the PS/2 story that also deserves its due. Existing in those seemingly misbegotten machines alongside MCA and the cynicism it represented was a more positive, one might even say technically idealistic determination to advance the state of the art for this architecture that had long since become the mainstream face of computing, dwarfing in terms of the sheer money it generated any other platform.

And make no mistake: the world of the IBM compatibles was in sore need of advancement on multiple fronts. While machines like the Apple Macintosh and Commodore Amiga had opened whole new paradigms of computing — the former with its friendly GUI interface and crisp almost print-quality display, the latter with its multitasking operating system and implementation of the ideal of multimedia computing long before “multimedia” became a buzzword — the world of the clones had remained as bland as ever, a land of green or amber text-only displays, unpleasant beeps and squawks, and inscrutable command lines. For all the apparently proud users and sellers who took all this ugliness as a sign of serious businesslike intent, there were others who recognized that IBM and the clonesters had long since ceded the high ground of real, fundamental innovation in computing to rival platforms. Thankfully, some inside IBM were included in the latter group, and the results could be seen in the PS/2 machines.

Given how far the IBM-compatible world had fallen behind, it’s not surprising that many or most of the alleged innovations of the PS/2 were really a case of playing catch-up. For example, IBM finally produced their first-ever mouse for the line. They also switched over from the old, fragile 5.25-inch floppy-disk format to the newer, more robust and higher-capacity 3.5-inch format already being used by machines like the Macintosh and Amiga.

But undoubtedly the most welcome and significant of all the PS/2’s new technical developments were some desperately needed display improvements. The Video Graphics Array, or VGA, was included with the higher-end PS/2 models; lower-end models shipped with something called the Multi-Color Graphics Array (MCGA), with many but not quite all of the capabilities of VGA. After allowing their machines’ graphics capabilities to languish for years, IBM through VGA and to some extent MCGA finally brought them up to a level that compared very favorably with the Amiga. VGA and MCGA defined a palette of fully 262,144 colors, a huge leap over the 64 offered by the Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA), IBM’s previous best display option for their mainstream machines. The Amiga, by contrast, offered just 4096 colors, although its blitter and other custom hardware still gave it some notable advantages in the realm of fast animation.

All of these new developments marked IBM’s last great gifts to the standard they had birthed — gifts destined to long outlive the PS/2 line itself. The mouse connection IBM developed, for instance, remained a standard well beyond the millennium, with so-called “PS/2” connectors remaining common jargon, used by younger tech-heads and system builders who likely had only the vaguest idea from whence the usage derived. The VGA standard proved even longer-lived. It still survives today as the lowest-common-denominator baseline for computer displays, while ports matching the specification defined by IBM all those years ago remain on the back of every monitor and television set.

Ironically given IBM’s laser focus on using the PS/2 line to secure their dominance of business computing, its technical innovations ultimately proved most important in making the architecture viable as a proposition for the home, paving the way for the Microsoft-dominated second home-computer revolution of the 1990s. With good graphics falling into place at last thanks to VGA and the raw power of the 32-bit 80386, only two barriers remained to making PC-compatible machines realistic rivals to the likes of the Amiga as compelling home computers: decent sound to replace those atrocious beeps and squawks, and a decent price.

The first problem wouldn’t be a problem at all for very much longer. The first gaming-focused sound cards began to reach the market within a year of the PS/2 line’s debut, and by 1989 Creative Music Systems and Ad Lib both offered popular cards at street prices of $200 or less.

But the prices of home-oriented systems incorporating all of the PS/2 line’s innovations — MCA excepted — would, alas, take a little longer to fall. As late as July of 1989, when the VGA standard was already more than two years old, Computer Gaming World ran an article titled “Is VGA Worth It?” that seriously questioned whether it was indeed worth the still very considerable expense — VGA boards still cost $500 or more — to so equip a machine, especially given how few games supported VGA at that point. Nor did the 80386 find an immediate place in homes. As the 1980s turned into the 1990s, the newer chip was still a piece of pricey exotica in terms of the average consumer’s budget; the vast majority of the Intel-based PCs that were in consumers’ homes were still built around the 80286 or even the venerable old 8088.

Still, in the long run prices could only fall in such a hyper-competitive market. Given Commodore’s lackadaisical attitude toward improving the Amiga and Apple’s almost complete neglect of the consumer market in their eagerness to force the Macintosh into the offices of corporate America, the emerging standard of a 32-bit Intel-based PC with VGA graphics and a sound card came to the fore effectively unopposed. With the Internet having yet to emerge as home computing’s killer app to end all killer apps, it was games that drove this shift. In 1989, an Amiga was still the ultimate gaming computer. By 1991, it was an afterthought for American game publishers, the market being absolutely dominated by what was now starting to be called the “Wintel” standard. While game consoles and mobile devices have come and gone by the handful over the years since, in the realm of desktop- and laptop-based personal computing the heirs of the original IBM PC remain the overwhelming standard to this day. How ironic that this decades-long dominance was ensured by the PS/2, simultaneously the downfall of IBM and the savior of the inadvertently standard architecture IBM created.

(Sources: the books Big Blues: The Unmaking of IBM by Paul Carroll, Open: How Compaq Ended IBM’s PC Domination and Helped Invent Modern Computing by Rod Canion, and Hard Drive: Bill Gates and Making of the Microsoft Empire by James Wallace and Jim Erickson; Byte of June 1987, July 1987, August 1987, and December 1987; Compute! of June 1988, January 1989, and March 1989; Computer Gaming World of July 1989 and September 1989; Wall Street Journal of September 14 1988; the episodes of The Computer Chronicles titled “Intel 386 — The Fast Lane,” “IBM Personal System/2,” and “Bus Wars.”)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The full story of OS/2 and the Presentation Manager and their relationship to Microsoft Windows and even Apple’s MacOS is a complex yet fascinating one, but also one best reserved for a future article where I can give it its proper due. |

|---|