Fair Warning: this article contains plot spoilers for Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge and The Curse of Monkey Island. No puzzle spoilers, however…

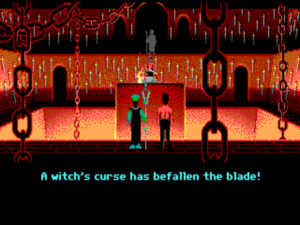

The ending of 1991’s Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge seems as shockingly definitive in its finality as that of the infamous last episode of the classic television series St. Elsewhere. Just as the lovable wannabe pirate Guybrush Threepwood is about to finally dispatch his arch-nemesis, the zombie pirate LeChuck, the latter tears off his mask to reveal that he is in reality Guybrush’s older brother, looking a trifle peeved but hardly evil or undead. Guybrush, it seems, is just an ordinary suburban kid who has wandered away from his family to play make-believe inside a storage room at Big Whoop Amusement Park, LeChuck the family member who has been dispatched to find him. An irate janitor appears on the scene: “Hey, kids! You’re not supposed to be in here!” And so the brothers make their way out to rejoin their worried parents, and another set of Middle American lives goes on.

Or do they? If you sit through the entirety of the end credits, you will eventually see a short scene featuring the fetching and spirited Elaine, Guybrush’s stalwart ally and more equivocal love interest, looking rather confused back in the good old piratey Caribbean. ‘I wonder what’s keeping Guybrush?” she muses. “I hope LeChuck hasn’t cast some horrible SPELL over him or anything.” Clearly, someone at LucasArts anticipated that a day might just come when they would want to make a third game.

Nevertheless, for a long time, LucasArts really did seem disposed to let the shocking ending stand. Gilbert himself soon left the company to found Humongous Entertainment, where he would use the SCUMM graphic-adventure engine he had helped to invent to make educational games for youngsters, even as LucasArts would continue to evolve the same technology to make more adventure games of their own. None of them, however, was called Monkey Island for the next four years, not even after the first two games to bear that name became icons of their genre.

Still, it is a law of the games industry that sequels to hit games will out, sooner or later and one way or another. In late 1995, LucasArts’s management decided to make a third Monkey Island at last. Why they chose to do so at this particular juncture isn’t entirely clear. Perhaps they could already sense an incipient softening of the adventure market — a downturn that would become all too obvious over the next eighteen months or so — and wanted the security of such an established name as this one if they were to invest big bucks in another adventure project. Or perhaps they just thought they had waited long enough.

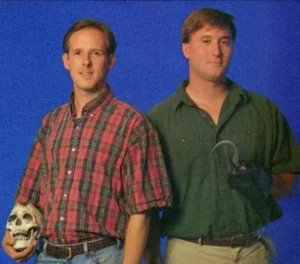

Whatever their reasoning in beginning the project, they chose for the gnarly task of succeeding Ron Gilbert an in-house artist and a programmer, a pair of good friends who had been employed at LucasArts for years and were itching to move into a design role. Larry Ahern had been hired to help draw Monkey Island 2 and had gone on to work on most of LucasArts’s adventure games since, while Jonathan Ackley had programmed large parts of Day of the Tentacle and The Dig. Knowing of their design aspirations, management came to them one day to ask if they’d like to become co-leads on a prospective Monkey Island 3. It was an extraordinary amount of faith to place in such unproven hands, but it would not prove to have been misplaced.

“We were too green to suggest anything else [than Monkey Island 3], especially an original concept,” admits Ahern, “and were too dumb to worry about all the responsibility of updating a classic game series.” He and Ackley brainstormed together in a room for two months, hashing out the shape of a game. After they emerged early in 1996 with their design bible for The Curse of Monkey Island in hand, production got underway in earnest.

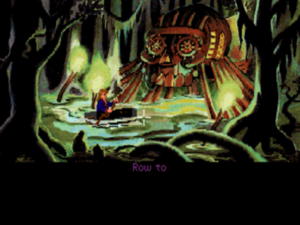

At the end of Monkey Island 2, Ahern and Ackley announced, Guybrush had indeed been “hexed” by LeChuck into believing he was just a little boy in an amusement park. By the beginning of the third game, he would have snapped back to his senses, abandoning mundane hallucination again for a fantastical piratey reality.

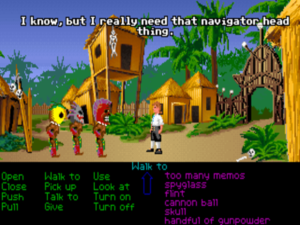

A team that peaked at 50 people labored over The Curse of Monkey Island for eighteen months. That period was one of dramatic change in the industry, when phrases like “multimedia” and “interactive movie” were consigned to the kitschy past and first-person shooters and real-time strategies came to dominate the sales charts. Having committed to the project, LucasArts felt they had no choice but to stick with the old-school pixel art that had always marked their adventure games, even though it too was fast becoming passé in this newly 3D world. By way of compensation, this latest LucasArts pixel art was to be more luscious than anything that had come out of the studio before, taking advantage of a revamped SCUMM engine that ran at a resolution of 640 X 480 instead of 320 X 200.

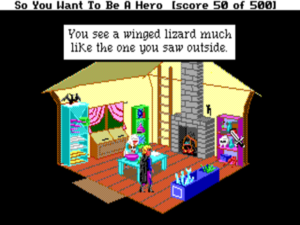

The end result is, in the opinion of this critic at least, the loveliest single game in terms of pure visuals that LucasArts ever produced. Computer graphics and animation, at LucasArts and elsewhere, had advanced enormously between Monkey Island 2 and The Curse of Monkey Island. With 1993’s Day of the Tentacle and Sam and Max Hit the Road, LucasArts’s animators had begun producing work that could withstand comparison to that of role models like Chuck Jones and Don Bluth without being laughed out of the room. (Indeed, Jones reportedly tried to hire Larry Ahern and some of his colleagues away from LucasArts after seeing Day of the Tentacle.) The Curse of Monkey Island marked the fruition of that process, showing LucasArts to have become a world-class animation studio in its own right, one that could not just withstand but welcome comparison with any and all peers who worked with more traditional, linear forms of media. “We were looking at Disney feature animation as our quality bar,” says Ahern.

That said, the challenge of producing a game that still looked like Monkey Island despite all the new technical affordances should not be underestimated. The danger of the increased resolution was always that the finished results could veer into a sort of photo-realism, losing the ramshackle charm that had always been such a big part of Monkey Island‘s appeal. This LucasArts managed to avoid; in the words of The Animation World Network, a trade organization that was impressed enough by the project to come out and do a feature on it, Guybrush was drawn as “a pencil-necked beanpole with a flounce of eighteenth-century hair and a nose as vertical as the face of Half Dome.” The gangling frames and exaggerated movements of Guybrush and many of the other characters were inspired by Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. Yet the characters aren’t grotesques; The Curse of Monkey Island aims to be lovable, and it hits the mark. For this game is written as well as drawn in the spirit of the original Secret of Monkey Island, abandoning the jarring mean-spiritedness that dogs the second game in the series, a change in tone that has always left me a lot less positively disposed toward it than most people seem to be.

This was the first Monkey Island game to feature voice acting from the outset, as telling a testament as any to the technological gulf that lies between the second and third entries in the series. The performances are superb — especially Guybrush, who sounds exactly like I want him to, all gawky innocence and dogged determination. (His voice actor Dominic Armato would return for every single Monkey Island game that followed, as well as circling back to give Guybrush a voice in the remastered versions of the first two games. I, for one, wouldn’t have it any other way.)

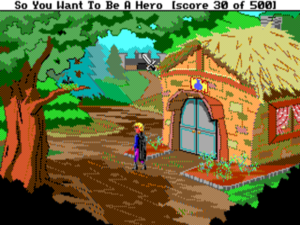

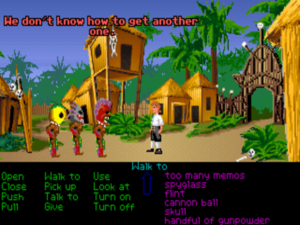

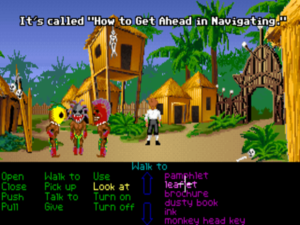

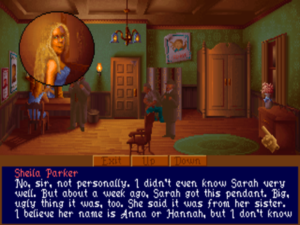

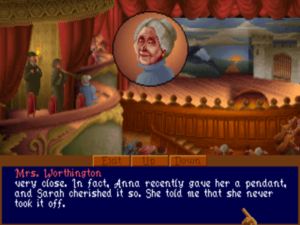

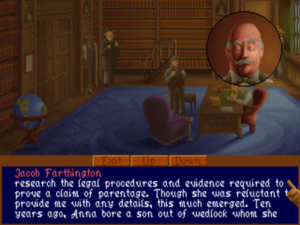

The opening sees Guybrush adrift on the open ocean in, of all forms of conveyance, a floating bumper car, for reasons that aren’t initially clear beyond the thematic connection to that amusement park at the end of Monkey Island 2. He floats smack-dab into the middle of a sea battle between LeChuck and Elaine; the former is trying to abduct the latter to make her his bride, while the latter is doing her level best to maintain her single status. Stuff happens, LeChuck seems to get blown up, and Guybrush and Elaine wind up on Plunder Island, a retirement community for aging pirates that’s incidentally also inhabited by El Pollo Diablo, the giant demon chicken. (“He’s hatching a diabolical scheme”; “He’s establishing a new pecking order”; “He’s going to buck buck buck the system”; “He’s crossing the road to freedom”; etc.) Guybrush proposes to Elaine using a diamond ring he stole from the hold of LeChuck’s ship, only to find that there’s a voodoo curse laid on it. Elaine gets turned into a solid-gold statue (d’oh!), which Guybrush leaves standing on the beach while he tries to figure out what to do about the situation. Sure enough, some opportunistic pirates — is there any other kind? — sail away with it. (Double d’oh!) Guybrush is left to scour Plunder Island for a ship, a crew, and a map that will let him follow them to Blood Island, where there is conveniently supposed to be another diamond ring that can reverse the curse.

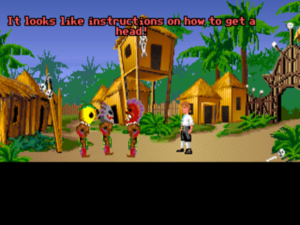

The vicious chickens of Plunder Island. “Larry and I thought we were so clever when we came up with the idea of having a tropical island covered with feral chickens,” says Jonathan Ackley. “Then I took a vacation to the Hawaiian island of Kauai. It seems that when Kauai was hit by Hurricane Iniki, it blew open all the chicken coops. Everywhere I went on the island I was surrounded by feral chickens.”

From the shopping list of quest items to the plinking steelband soundtrack that undergirds the proceedings, all of this is a dead ringer for The Secret of Monkey Island; this third game is certainly not interested in breaking any new ground in setting, story, or genre. But when it’s done this well, who cares? There is a vocal segment of Monkey Island fans who reject this game on principle, who say that any Monkey Island game without the name of Ron Gilbert first on its credits list is no Monkey Island game at all. For my own part, I tend to believe that, if we didn’t know that Gilbert didn’t work on this game, we’d have trouble detecting that fact from the finished product. It nails that mixture of whimsy, cleverness, and sweetness that has made The Secret of Monkey Island arguably the most beloved point-and-click adventure game of all time.

During the latter 1990s, when most computers games were still made by and for a fairly homogeneous cohort of young men, too much ludic humor tried to get by on transgression rather than wit; this was a time of in-groups punching — usually punching down — on out-groups. I’m happy to say that The Curse of Monkey Island‘s humor is nothing like that. At the very beginning, when Guybrush is floating in that bumper car, he scribbles in his journal about all the things he wishes he had. “If only I could have a small drink of freshwater, I might have the strength to sail on.” A bottle of water drifts past while Guybrush’s eyes are riveted to the page. “If I could reach land, I might find water and some food. Fruit maybe, something to fight off the scurvy and help me get my strength back. Maybe some bananas.” And a crate of bananas drifts by in the foreground. “Oh, why do I torture myself like this? I might as well wish for some chicken and a big mug of grog, for all the good it will do me.” Cue the clucking chicken perched on top of a barrel. Now, you might say that this isn’t exactly sophisticated humor, and you’d be right. But it’s an inclusive sort of joke that absolutely everyone is guaranteed to understand, from children to the elderly, whilst also being a gag that I defy anyone not to at least smirk at. Monkey Island is funny without ever being the slightest bit cruel — a combination that’s rarer in games of its era than it ought to be.

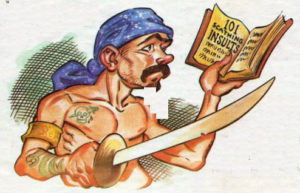

Which isn’t to say that this game is without in-jokes. They’re everywhere, and the things they reference are far from unexpected. Star Trek gets a shout-out in literally the first line of the script as Guybrush writes in his “captain’s log,” while, appropriately enough given the studio that made this game, whole chunks of dialogue are re-contextualized extracts from the Star Wars movies. The middle of the game is an extended riff on/parody of that other, very different franchise that springs to mind when gamers think about pirates — the one started by Sid Meier, that’s known as simply Pirates!. Here as there, you have to sail your ship around the Caribbean engaging in battles with other sea dogs. But instead of dueling the opposing captains with your trusty cutlass when you board their vessels, here you challenge them to a round of insult sword-fighting instead. (Pirate: “You’re the ugliest monster ever created!” Guybrush: “If you don’t count all the ones you’ve dated!”)

One of the game’s best gags is an interactive musical number you perform with your piratey crew, feeding them appropriate rhymes. “As far as I know, nobody had ever done interactive singing before,” says Jonathan Ackley. “I think it was an original idea and I still laugh when I see it.” Sadly, the song was cut from the game’s foreign localizations as a bridge too far from its native English, even for LucasArts’s superb translators.

It shouldn’t work, but somehow it does. In fact, this may just be my favorite section of the entire game. Partly it succeeds because it’s just so well done; the action-based minigame of ship-to-ship combat that precedes each round of insult sword-fighting is, in marked contrast to those in LucasArts’s previous adventure Full Throttle, very playable in its own right, being perfectly pitched in difficulty, fun without ever becoming frustrating. But another key to this section’s success is that you don’t have to know Pirates! for it to make you laugh; it’s just that, if you do, you’ll laugh that little bit more. All of the in-jokes operate the same way.

Pirates! veterans will feel right at home with the ship-combat minigame. It was originally more complicated. “When I first started the ship-combat section,” says programmer Chris Purvis, “I had a little readout that told how many cannons you had, when they were ready to fire, and a damage printout for when you or the computer ships got hit. We decided it was too un-adventure-gamey to leave it that way.” Not to be outdone, a member of the testing team proposed implementing multiplayer ship combat as “the greatest Easter egg of all time for any game.” Needless to say, it didn’t happen.

The puzzle design makes for an interesting study. After 1993, the year of Day of the Tentacle and Sam and Max Hit the Road, LucasArts hit a bumpy patch in this department in my opinion. Both Full Throttle and The Dig, their only adventures between those games and this one, are badly flawed efforts when it comes to their puzzles, adhering to the letter but not the spirit of Ron Gilbert’s old “Why Adventure Games Suck” manifesto. And Grim Fandango, the adventure that immediately followed this one, fares if anything even worse in that regard. I’m pleased if somewhat perplexed to be able to say, then, that The Curse of Monkey Island mostly gets its puzzles right.

There are two difficulty levels here, an innovation borrowed from Monkey Island 2. Although the puzzles at the “Mega-Monkey” level are pretty darn convoluted — one sequence involving a restaurant and a pirate’s tooth springs especially to mind as having one more layer of complexity than it really needs to — they are never completely beyond the pale. It might not be a totally crazy idea to play The Curse of Monkey Island twice, once at the easy level and once at the Mega-Monkey level, with a few weeks or months in between your playthroughs. There are very few adventure games for which I would make such a recommendation in our current era of entertainment saturation, but I think it’s a reasonable one in this case. This game is stuffed so full of jokes both overt and subtle that it can be hard to take the whole thing in in just one pass. Your first excursion will give you the lay of the land, so to speak, so you know roughly what you’re trying to accomplish when you tackle the more complicated version.

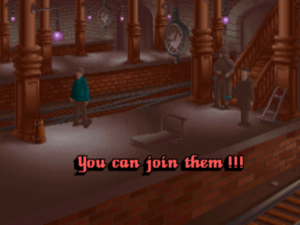

Regardless of how you approach it, The Curse of Monkey Island is a big, generous adventure game by any standard. I daresay that the part that takes place on Plunder Island alone is just about as long as the entirety of The Secret of Monkey Island. Next comes the Pirates! homage, to serve as a nice change of pace at the perfect time. And then there’s another whole island of almost equal size to the first to explore. After all that comes the bravura climax, where LeChuck makes his inevitable return; in a rather cheeky move, this ending too takes place in an amusement park, with Guybrush once again transformed into a child.

If I was determined to find something to complain about, I might say that the back half of The Curse of the Monkey Island isn’t quite as strong as the front half. Blood Island is implemented a little more sparsely than Plunder Island, and the big climax in particular feels a little rushed and truncated, doubtless the result of a production budget and schedule that just couldn’t be stretched any further if the game was to ship in time for the 1997 Christmas season. Still, these are venial sins; commercial game development is always the art of the possible, usually at the expense of the ideal.

When all is said and done, The Curse of Monkey Island might just be my favorite LucasArts adventure, although it faces some stiff competition from The Secret of Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle. Any points that it loses to Secret for its lack of originality in the broad strokes, it makes up for in size, in variety, and in sheer gorgeousness.

Although I have no firm sales figures to point to, all indications are that The Curse of Monkey Island was a commercial success in its day, the last LucasArts adventure about which that statement can be made. I would guess from anecdotal evidence that it sold several hundred thousand copies, enough to convince the company to go back to the Monkey Island well one more time in 2000. Alas, the fourth game would be far less successful, both artistically and commercially.

These things alone are enough to give Curse a valedictory quality today. But there’s more: it was also the very last LucasArts game to use the SCUMM engine, as well as the last to rely primarily on pixel art. The world-class cartoon-animation studio that the company’s adventure division had become was wound down after this game’s release, and Larry Ahern and Jonathan Ackley were never given a chance to lead a project such as this one again, despite having acquitted themselves so well here. That was regrettable, but not incomprehensible. Economics weren’t working in the adventure genre’s favor in the late 1990s. A game like The Curse of Monkey Island was more expensive to make per hour of play time it provided than any other kind of game you could imagine; all of this game’s content was bespoke content, every interaction a unique one that had to be written and story-boarded and drawn and painted and animated and voiced from scratch.

The only way that adventure games — at least adventures with AAA production values like this one — could have remained an appealing option for gaming executives would have been if they had sold in truly massive numbers. And this they emphatically were not doing. Yes, The Curse of Monkey Island did reasonably well for itself — but a game like Jedi Knight probably did close to an order of magnitude better, whilst probably costing considerably less to make. The business logic wasn’t overly complicated. The big animation studios which LucasArts liked to see as their peers could get away with it because their potential market was everyone with a television or everyone who could afford to buy a $5 movie ticket; LucasArts, on the other hand, was limited to those people who owned fairly capable, modern home computers, who liked to solve crazily convoluted puzzles, and who were willing and able to drop $40 or $50 for ten hours or so of entertainment. The numbers just didn’t add up.

In a sense, then, the surprise isn’t that LucasArts made no more games like this one, but rather that they allowed this game to be finished at all. Jonathan Ackley recalls his reaction when he saw Half-Life for the first time: “Well… that’s kind of it for adventure games as a mainstream, AAA genre.” More to their credit than otherwise, the executives at LucasArts didn’t summarily abandon the adventure genre, but rather tried their darnedest to find a way to make the economics work, by embracing 3D modelling to reduce production costs and deploying a new interface that would be a more natural fit with the tens of millions of game consoles that were out there, thus broadening their potential customer base enormously. We’ll get to the noble if flawed efforts that resulted from these initiatives in due course.

For today, though, we raise our mugs of grog to The Curse of Monkey Island, the last and perhaps the best go-round for SCUMM. If you haven’t played it yet, by all means, give it a shot. And even if you have, remember what I told you earlier: this is a game that can easily bear replaying. Its wit, sweetness, and beauty remain undiminished more than a quarter of a century after its conception.

The Curse of Monkey Island: The Graphic Novel

(I’ve cheerfully stolen this progression from the old Prima strategy guide to the game…)

…but manages to escape, sending LeChuck’s ship to the bottom in the process. Thinking LeChuck finally disposed of, Guybrush proposes to Elaine, using a diamond ring he found in the zombie pirate’s treasure hold…

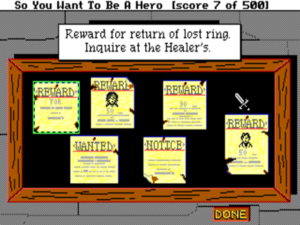

Guybrush sets off to discover a way to break the curse — and to rescue Elaine, since her statue is promptly stolen. His old friend the voodoo lady tells him he will need a ship, a crew, and a map to Blood Island, where he can find a second diamond ring that will reverse the evil magic of the first.

…and a cabana boy, before he is finally able to set sail for Blood Island.

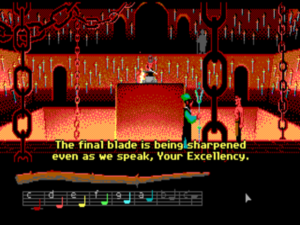

Unfortunately, as soon as Elaine is uncursed, the two are captured by LeChuck and taken to the Carnival of the Damned on Monkey Island.

LeChuck turns Guybrush into a little boy and attempts to escape with Elaine on his hellish roller coaster.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book The Curse of Monkey Island: The Official Strategy Guide by Jo Ashburn. Retro Gamer 70; Computer Games Strategy Plus of August 1997; Computer Gaming World of October 1995, March 1996, September 1997, November 1997, December 1997, and March 1998.

Online sources include a Genesis Temple interview with Larry Ahern, an International House of Mojo interview with Jonathan Ackley and Larry Ahern, the same site’s archive of old Curse of Monkey Island interviews, and a contemporaneous Animation World Network profile of LucasArts.

Also, my heartfelt thanks to Guillermo Crespi and other commenters for pointing out some things about the ending of Monkey Island 2 that I totally overlooked in my research for the first version of this article.

The Curse of Monkey Island is available for digital purchase at GOG.com.