It’s easy to dismiss Michael Crichton. Following his shocking 2008 death from throat cancer at age 66 (few had even been aware he was ill), virtually all of the obituaries and memorials took a tack similar to that of Charles McGrath in The New York Times: “No one — except possibly Mr. Crichton himself — ever confused them [his novels] with great literature, but very few readers who started a Crichton novel ever put it down.” One somehow feels the need to qualify that, yes, one understands he’s not great literature or anything before one admits to enjoying a Michael Crichton book. That’s kind of odd when you think about it. Readers of J.K. Rowling or Stephen King don’t seem to wax defensive quite so quickly or in quite such quantities.

If we take the relatively accepted and non-controversial definition of hard science fiction as a story that begins with the words “What if…” and then proceeds to try to rationally work through the consequences of that opening proposition, many of Crichton’s stories are virtual textbook examples of the genre. His breakout novel, The Andromeda Strain, asked what if a satellite returned to earth bearing a deadly extraterrestrial microbe; his most successful of all, Jurassic Park, asked what if dinosaur DNA could be recovered and cloned. Yet he was never really embraced by hardcore science-fiction readers. Something about Crichton was just too slick, too commercially calculated, too darn ubiquitous to be embraced by scruffy fan communities. He just wasn’t one of them. Instead he became the king of that genre unto itself of airport fiction, his latest bestseller — everything he released after The Andromeda Strain was a bestseller — to be found clutched under the arms of business travelers, as much a part of that strange artificial environment as X-ray machines, processed air, and canned announcements saying something about baggage left unattended. These folks wanted something to read that was neither embarrassing nor aggressively stupid but also not too taxing while they hurried up and waited. Crichton knew exactly where that perfect median lay, and he delivered every time.

All of which can make it a little bit hard to get really excited about Michael Crichton. I have a theory that, for all his ubiquity, relatively few people would claim him as their favorite writer — and those who do probably in all honesty don’t read a whole lot of books. Still, his achievements are kind of amazing. Educated as a doctor but never actually licensed to practice medicine, he was seemingly interested in everything and pretty good at a fair number of those things. And, like Steve Jobs and Byron Preiss, Crichton had looks and charm on his side as well. (People magazine named him one of their “50 Most Beautiful People” in the world in 1992, a rare honor indeed for a writer and general behind-the-camera type.) In 1970, in the aftermath of The Andromeda Strain‘s success, he abandoned his medical fellowship and set out to conquer the world of film. Despite having no background whatsoever in filmmaking, he convinced MGM to let him direct his own screenplay of Westworld in 1973. From there Crichton maintained parallel careers in the worlds of letters and film. It’s difficult to say which was more successful, especially since the latter so obviously fed off the former; every one of his first ten novels became a film, often with Crichton himself screenwriting, directing, and/or producing. And then, from the realm of Things Completely Different, let’s not forget that Crichton also created one of the most long-running and popular television dramas in history, E.R.

Clearly Crichton’s commercial instincts were well-honed. He always seemed to have the right book for the times, jumping on the newest trends and fears in popular science and the zeitgeist in general: the Hong Kong Flu (The Andromeda Strain, 1969); the first widespread discussion of cloning and its implications (Jurassic Park, 1990); workplace sexual harassment in the wake of the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings (Disclosure, 1994); the global-warming debate (State of Fear, 2004). If he was still with us, I’m sure Crichton would have a book for the latest pop-science fad for all things neuroscience.

So, yes, there was a certain amount of calculation to Michael Crichton — but that’s not all there was. Yes, sometimes he oversimplified, and sometimes he got things just plain wrong, but most of Crichton’s books evidence more research than their sensational thriller plots — not to mention the feckless Hollywood blockbusters based on them — might suggest. Crichton was genuinely curious about the world around him, and genuinely worked to inform as well as entertain. Or, perhaps better stated, to entertain by informing, because the subjects he tackled are often genuinely fascinating. His peculiar genius was really composed of three parts: a deep sense of the current zeitgeist in science, technology, politics; a flair for explaining complicated ideas in an understandable, readable way (he could have been one heck of a “pure” pop-science writer if he’d wanted to); and the ability to tie the aforementioned talents to breakneck plots guaranteed to keep you turning the pages. We can see all of these elements at work in 1980’s Congo, generally regarded as one of his better books if also one that demonstrates some of his failings.

In typical Crichton fashion, Congo begins with an attack: an expedition encamped next to a heretofore undiscovered ancient city deep in the Congo Rainforest is ambushed and massacred by gorillas, or at least some somethings that are distinctly gorilla-like. The expedition had come there not for the sake of archaeology but to search for diamonds — special diamonds, meant to serve not as ornamentation but as the heart of a new generation of computers to be built using optical circuits instead of electric, made out of diamonds instead of silicon. Current computers, Crichton eventually explains, have gotten just as small and fast as they can with silicon chips. Like many specific predictions and extrapolations in Crichton novels, this is spectacularly wrong, as a quick comparison between, say, an Apple II and an iPad, both based on good old silicon, will demonstrate. But hey, where would a thriller writer (or pop-science writer, for that matter) be without a bit of hyperbole?

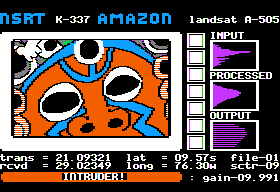

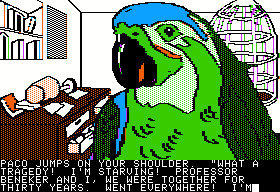

More prescient and interesting is the nature of the company that sent the unfortunate team into the field. Earth Resources Technology Services is like the Google of geology, scouring the planet on behalf of their clients to find mineral deposits of all stripes and stake claim to them. They are, to use a modern term, a data-driven organization, at least by the standards of 1980; ERTS stores “two million images” on their central computer, with new ones coming in at the staggering rate of “thirty images an hour.” They must inevitably send teams of people out to investigate promising sites in person, but the teams do their best to maintain satellite connections with ERTS headquarters in Houston. It’s thanks to this that ERTS gets to watch their team get killed in real-time. Not being idealistic sorts, they judge that this site is just too juicy to let a few killer apes and dead employees stand in their way. They mount a new expedition, which becomes the subject of the book. It’s led by one Karen Ross, who looks “the very flower of virile Texas womanhood” but entered MIT at age 13. For reasons that are rather tenuous at best, she decides to bring along a sign-language-using gorilla named Amy and her trainer, the diffident scientist Peter Elliot. The cast is rounded out by a grizzled ex-mercenary with a shady past named Munro and a jolly but mysterious group of native porters whom you just know are going to be the first to die. With our adventure-novel archetypes all in place, we’re off.

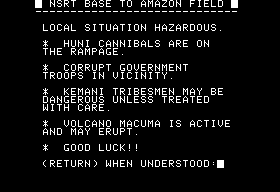

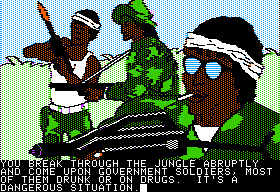

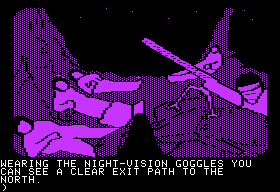

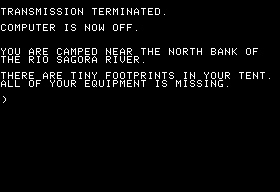

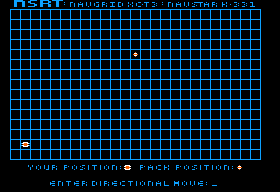

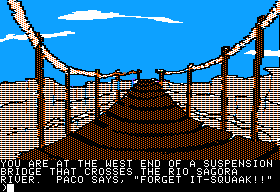

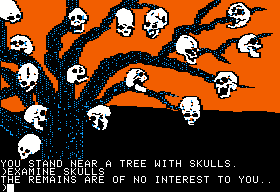

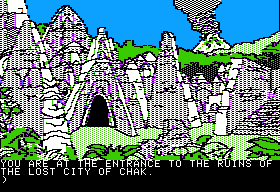

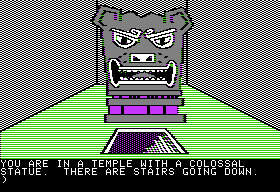

The structure of what follows is lumpy and kind of odd, but very typical of Crichton. About half of the text is devoted to a thrill-a-minute adventure story as the team penetrates deeper and deeper into the heart of the Dark Continent and into ever greater peril. Crichton meant it to be, besides being a crackerjack thriller in its own right, an homage to classic adventure fiction like The Lost World and King Solomon’s Mines; Crichton’s Lost City of Zinj and its diamond mines are in fact sourced from the same legends as the latter book. But Crichton, to his credit, doesn’t just try to ape adventure fiction of earlier generations. His heroes are thoroughly up to date, with all the latest gadgets. Thus they may be wandering through the jungle dodging cannibals, rampaging army troops, and strange hostile gorillas, but they’re also using their portable computer to link up with ERTS for all manner of assistance as they try to beat a rival high-tech consortium to the prize. (Admittedly, this assistance can sometimes be a bit too helpful, leaving Crichton with something of the classic Star Trek transporter dilemma: i.e., how can we have real drama when Captain Kirk can just shout “Beam me up, Scotty!” into his communicator as soon as things start to get hairy? Like the Star Trek writers, Crichton must often contrive circumstances — a freak solar flare, etc. — to cut off his heroes from their lifeline.)

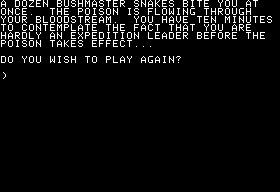

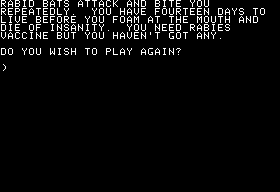

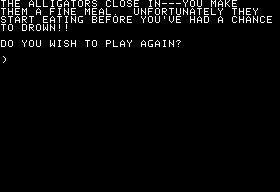

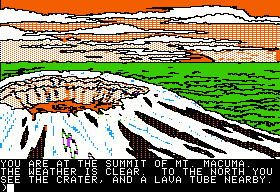

Crichton, as even his worst detractors will admit, is good at constructing the skeleton of compelling suspense fiction. He knows how to build a roller coaster of a plot and let it run, knows how to keep you turning the pages to find out how they’re gonna get out of this one — even if he does wrap things up in this case via a classic deus ex machina of a volcano that’s been dormant for thousands of years suddenly deciding to erupt the very week our heroes visit.

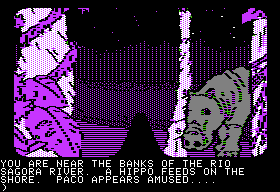

But intertwined with the thriller is the pop-science book. Crichton loves his research, and loves to share what he’s learned with us. So we get often pages-long digressions on all sorts of things: the state of computing circa 1980 (lots of this, delving into lots of sub-topics); primates’ capacities for language learning (ditto); satellite-imaging technology; volcanoes; the strange customs of African cannibal tribes; the race among China, the Soviet Union, and the United States to exploit Africa’s vast mineral wealth; the hippopotamus in nature and in human culture; the vanishing rain forests; etc, etc. The pattern is always the same: during the story part of the novel some character, or Crichton the narrator himself, will make reference to some scientist, some event, some technology. Then it’s time to put the story on hold and start with the infodump.

By all rights this structure ought to be infuriating — but somehow Crichton makes it work. Perhaps it’s partly because most of the topics he writes about are genuinely interesting. Certainly it’s largely down to the fact that Crichton is a good writer within his sphere, able to make his factual material as engaging as his fiction. But maybe it’s also caught up with something else about Crichton, something I don’t even know whether I should label a flaw precisely because I think it’s actually a big part of his appeal as an author of airport fiction: the peculiar sense of distance about the whole exercise.

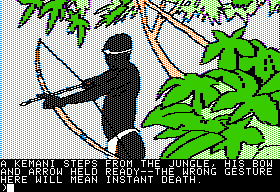

By the final chapters of Congo the situation is truly desperate. Our hardy band of heroes camped on the outskirts of Zinj are enduring nightly attacks by hundreds of remorseless killer gorillas. Already almost half their party — all native porters naturally; can’t start killing the heroes too soon — have been killed. Supplies are dwindling, ammunition almost exhausted. Worst of all, they can’t even try to escape back out into the jungle and take their chances with the roving bands of cannibals; the gorillas wait in ambush at the choke point which is the only way out of the valley in which they’ve encamped. And now, to top it all off, the volcano just above them is rumbling ominously. The horror of the situation should be palpable. Yet Crichton continues merrily along in the mode he established from the beginning, ticking off events as they occur and infodumping in between about gorilla behavior, gorilla populations, the cause and frequency of solar flares, the nature of language. He doesn’t do our imaginations any favors; any palpable fear or sense of real identification with the party will have to come from ourselves alone. Even his heroes seem oddly oblivious to their situation. No one seems to care all that much when the porters start getting killed. They’re much more concerned about their satellite connection and where those diamonds might be buried.

This strangely disembodied quality infects the whole book. Instead of giving us a tactile sense of the still primordial continent of Africa, inspiration for so many truly great books (Heart of Darkness; Out of Africa; The Green Hills of Africa), he infodumps statistics at us: that each tree has a trunk 40 feet in diameter and rises 200 feet, that there are four times as many species of animal life here as in a typical forest ecosystem. Add in Crichton’s less than engaging characters, who are if anything even more wooden than Arthur C. Clarke’s, and we’re left feeling, shall we say, somewhat removed from the action. We’re interested to find out what’s going to happen, but almost as an intellectual exercise rather than out of any sense of empathy. Nobody’s going to lose a lot of sleep if such refugees from Hollywood central casting as Karen Ross the Frigid Beauty or Munro the Shady Former Mercenary should buy it. By far the most memorable and endearing character in the book is Amy the signing gorilla.

Despite all of his research, there’s a certain facile quality to Crichton’s writing even when he sticks to facts. He is indeed shockingly prescient in imagining a company like ERTS, who deal only in hard data and seek to quantify absolutely everything, including the percentage chance their team has for finding diamonds and for getting themselves killed, which they coldly use to balance corporate risk and reward; diamonds are obviously worth some lives and the associated bad press and insurance payments. Yet he’s content to present ERTS’s corporate philosophy as just a neat new thing and move on. He never asks whether ERTS’s calculations and probabilities can replace more innate forms of human wisdom, or what it means that ERTS seem to think they can. Similarly, he mentions that Peter Elliot, trainer of Amy the gorilla, is being targeted by animal-rights groups, but he’s content to use this situation largely as a plot device to get Peter and Amy to Africa. Once that’s accomplished, it’s never mentioned again; he never addresses the legitimate ethical questions raised by inculcating an intelligent, empathetic animal into a human society in which it can never truly have a place beyond age seven or eight (the age at which a gorilla becomes too large, strong, and dangerous to safely interact with one-on-one). No, Crichton is happy to just label Elliot’s oppressors kooks and move on.

Like the wonks at ERTS, Crichton throws lots of facts at us and even comes to lots of conclusions, but never digs all that far beneath the surface. I think it’s this very facileness, this unwillingness to ever really make his reader — or, perhaps more importantly, himself — uncomfortable, that many people are subconsciously connecting with when they rush to make the disclaimer that Crichton certainly isn’t great literature or anything. Yet it also may be just what made him so popular. When all is said and done, and despite all the chaos and death and violence and potentially world-ending threats his books contain, he’s a comfort read. You’ll emerge from reading one of his books feeling pleasantly distracted and even a bit more educated about various esoteric subjects, but with worldview intact and bedrock assumptions unchallenged (assuming, of course, that said worldview and assumptions are comfortably Middle American like Crichton’s in the first place).

All of which probably reads more harshly than I really intend it. After I reread Congo for this blog for the first time in many years, my reaction may have been typical: “I enjoyed that… but I don’t need to read anything else by this author again.” On the other hand, if I was trapped alone in an airport somewhere with time on my hands, and Jurassic Park or Sphere or The Andromeda Strain was in the display window of the bookstore… well, I might just take the plunge. What else can I say? Crichton knew exactly what he was doing and did it well. If that makes him a craftsman rather than an artist, well, many other bestselling authors are neither.

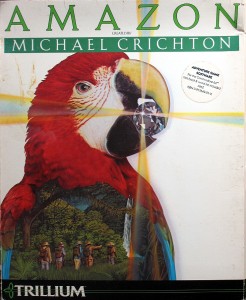

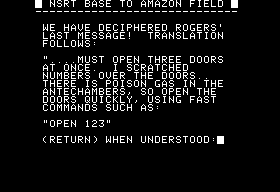

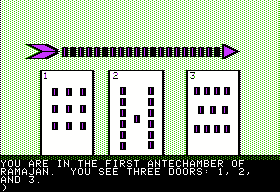

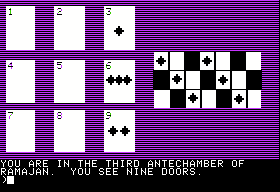

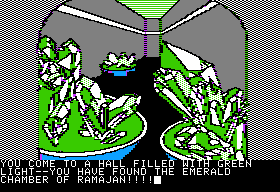

Amongst his other accomplishments, Crichton was also the most famous name ever to actively work in the medium of interactive fiction. (His only rival would be Stephen King — but while King’s story The Mist was adapted to interactive fiction, it was purely an exercise in licensing; thus the “actively.”) We’ll talk about how that happened and the game that resulted next time.

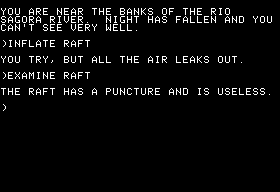

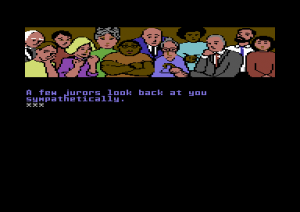

(The photo was taken from the February 1985 issue of Compute!.)