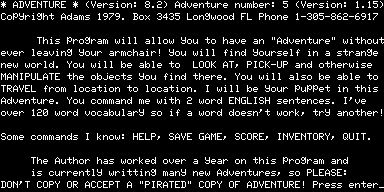

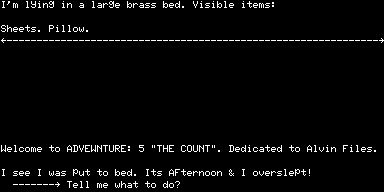

The Count opens with a title screen that would become iconic and almost bizarrely long-lived, finding its way not only to all of the other games in the classic Scott Adams series on the TRS-80 but to all of those other platforms on which the line would eventually arrive as well. Even when the games were ported to the illustrated SAGA system, this screen was little changed.

Looking at it, a few things are immediately striking. First there is Adams’s indelible, lackadaisically enthusiastic writing style that stamps all of his games better than could their maker’s signature. As near as I can tell, the interpreter is called simply ADVENTURE and is at version 8.2 already (!), while the game of The Count itself (“Adventure Number 5”) is at version 1.15. The plea which concludes the message shows that software piracy was already a significant problem in 1979, and not just a bugaboo of Bill Gates. As time went on, it would of course only become a bigger issue, as pirates formed sophisticated distribution networks and a whole fascinating if amoral subculture of their own; I’ll talk more about that when we get there. Still, Adams was himself not above stretching the truth a bit to get his point across; he obviously didn’t spend “over a year” developing The Count when he released five other games in 1979 alone. (Or perhaps he was referring to the system of ADVENTURE as a whole?)

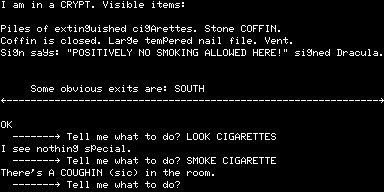

But, you might be asking, why does the text look so funny? Well, you may remember my saying that the standard TRS-80 did not come equipped with support for lower-case letters. In a sense, that’s only partially true. The character ROM, which contained the glyphs for all displayable characters, did have glyphs for all lower-case as well as upper-case letters; presumably it was, like most components of the TRS-80, an off-the-shelf part that was easier to leave alone than it would have been to modify to remove the extra glyphs. What the TRS-80 really lacked was a way to input lower-case. The ever-inventive aftermarket soon addressed this with various modification kits, one of which Adams had obviously acquired by early 1979. Even with the kit, though, the TRS-80’s display, having been designed with only upper-case in mind, still lacked the concept of descenders. Thus letters like “y,” “p,” and “g” are perched on the line rather than dangling below, creating the decidedly odd appearance you see in the image above. Like everything that doesn’t kill you, you get used to it.

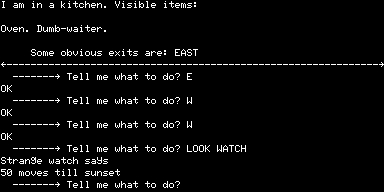

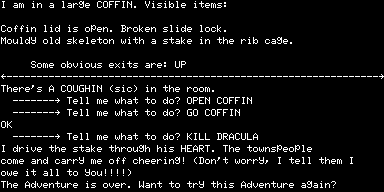

But now let me talk about The Count specifically, and what makes it such a unique and interesting entry in the Adams canon. While Mission Impossible had introduced the use of time in the direct service of plot in the form of a (literally) ticking time-bomb, The Count goes much, much further. As it begins, we wake up in a bedroom of a house that is being haunted by Dracula himself. We have been placed there by the frightened inhabitants of the local village, and given strict instructions to either kill Dracula or die — or, presumably, become a vampire ourselves — in the process. (Of course, thanks to the typically sparse text, lack of supporting documentation, and old-school design we infer all this only when we attempt to leave the house and get killed by an angry mob, all of which leaves one to wonder whether Dracula or the villagers are the more evil… but we’ll let all that go.) The plot unfolds over the next three — or, just possibly, four — afternoons and evenings, during which we must maneuver everything into position to finally administer the obligatory stake through the heart that ends Dracula’s reign.

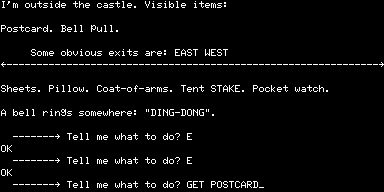

Not only does time pass over the course of these days, with afternoon trailing into night (with the expected effect on the general lighting situation), but there are actual plot-related events that happen in the storyworld, in the form of a pair of deliveries on the first and second afternoon.

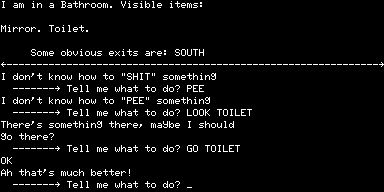

As always, we don’t want to go too far here; this still isn’t anything close to a serious, nuanced story, as the game remains firmly entrenched in the usual jokey Scott Adams style.

What we do have here, though, is a storyworld that is at least in some senses more dynamic than anything we’ve seen before; while Adventure could boast the independently moving dwarfs and pirate that were surprisingly sophisticated in their way, its world was otherwise static prior to the triggering of the endgame, and lacked any sense of time other than the expiring lantern. Notably, The Count adds a WAIT verb, a command that would have been superfluous in earlier games, as the player must plan her actions around the time of day and those all-important package deliveries.

In practice, the game plays out like a whole new type of systemic meta-puzzle, as the player maps out how events unfold and how everything works — dying countless times in the process — to come up with a final plan for victory. The Count introduces nothing less than a whole new paradigm of play for the text adventure, one focused not on geographic exploration (the map is very small and manageable for the era) but on dynamic, systemic thinking that feels much closer to engaging with a narrative. Its system is even sophisticated enough to support quite a number of different paths to victory; virtually every walkthrough for the game I was able to find has its own unique approach.

Still, at times the boundaries between the system of the storyworld and the system of the program are hazy, such that one is often left feeling one is playing the program rather than playing the story. For instance, one travels between floors using a dumbwaiter (the lack of a staircase is one of those sins against mimesis we can forgive in such an early, primitive game). If one passes out and is put to bed (presumably by Dracula) for the night while on another floor than the one containing the bedroom, the dumbwaiter is left on the former floor, locking one out of victory. This of course makes no sense in the storyworld — whoever heard of a dumbwaiter that can only be raised or lowered by someone riding on it? — but is a limitation of the program. Indeed, much about solving the game can be more tedious than fun; the learning-by-death syndrome is one that even Infocom would never entirely solve in its similarly dynamic mysteries. Frustrations like these make The Count perhaps less entertaining as a game than it is interesting as technology and as a concept; nor does its ending exactly pull out all the stops.

Adams himself didn’t do much to build on these concepts, largely retreating to treasure hunts and similarly static designs in subsequent games, leaving this approach to be taken up by Infocom three years later with the groundbreaking Deadline. But again, we’re getting ahead of ourselves…

If you’d like to play The Count in its original form yourself, here is a CMD file you can load into the MESS emulator using “Device –> Quickload” from the emulator menu.