Fair warning: this article includes some plot spoilers of Final Fantasy I through VI.

The videogame industry has always run on hype, but the amount of it that surrounded Final Fantasy VII in 1997 was unparalleled in its time. This new game for the Sony PlayStation console was simply inescapable. The American marketing teams of Sony and Square Corporation, the game’s Japanese developer and publisher, had been given $30 million with which to elevate Final Fantasy VII to the same status as the Super Marios of the world. They plastered Cloud, Aerith, Tifa, Sephiroth, and the game’s other soon-to-be-iconic characters onto urban billboards, onto the sides of buses, and into the pages of glossy magazines like Rolling Stone, Playboy, and Spin. Commercials for the game aired round the clock on MTV, during NFL games and Saturday Night Live, even on giant cinema screens in lieu of more traditional coming-attractions trailers. “They said it couldn’t be done in a major motion picture,” the stentorian announcer intoned. “They were right!” Even if you didn’t care a whit about videogames, you couldn’t avoid knowing that something pretty big was going down in that space.

And if you did care… oh, boy. The staffs of the videogame magazines, hardly known for their sober-mindedness in normal times, worked themselves up to positively orgasmic heights under Square’s not-so-gentle prodding. GameFan told its readers that Final Fantasy VII would be “unquestionably the greatest entertainment product ever created.”

The game is ridiculously beautiful. Analyze five minutes of gameplay in Final Fantasy VII and witness more artistic prowess than most entire games have. The level of detail is absolutely astounding. These graphics are impossible to describe; no words are great enough. Both map and battle graphics are rendered to a level of detail completely unprecedented in the videogame world. Before Final Fantasy VII, I couldn’t have imagined a game looking like this for many years, and that’s no exaggeration. One look at a cut scene or call spell should handily convince you. Final Fantasy VII looks so consistently great that you’ll quickly become numb to the power. Only upon playing another game will you once again realize just how fantastic it is.

But graphics weren’t all that the game had going for it. In fact, they weren’t even the aspect that would come to most indelibly define it for most of its players. No… that thing was, for the very first time in a mainstream console-based videogame with serious aspirations of becoming the toppermost of the poppermost, the story.

I don’t have any room to go into the details, but rest assured that Final Fantasy VII possesses the deepest, most involved story line ever in an RPG. There’s few games that have literally caused my jaw to drop at plot revelations, and I’m most pleased to say that Final Fantasy VII doles out these shocking, unguessable twists with regularity. You are constantly motivated to solve the latest mystery.

So, the hype rolled downhill, from Square at the top to the mass media, then on to the hardcore gamer magazines to ordinary owners of PlayStations. You would have to have been an iconoclastic PlayStation owner indeed not to be shivering with anticipation as the weeks counted down toward the game’s September 7 release. (Owners of other consoles could eat their hearts out; Final Fantasy VII was a PlayStation exclusive.)

Just last year, a member of an Internet gaming forum still fondly recalled how

the lead-up for the US launch of this game was absolutely insane, and, speaking personally, it is the most excited about a game I think I had ever been in my life, and nothing has come close since then. I was only fifteen at the time, and this game totally overtook all my thoughts and imagination. I had never even played a Final Fantasy game before, and I didn’t even like RPGs, yet I would spend hours reading and rereading all the articles from all the gaming magazines I had, inspecting all the screenshots and being absolutely blown away at the visual fidelity I was witnessing. I spent multiple days/hours with my Sony Discman listening to music and drawing the same artwork that was in all the mags. It was literally a genre- and generation-defining game.

Those who preferred to do their gaming on personal computers rather than consoles might be excused for scoffing at all these breathless commentators who seemed to presume that Final Fantasy VII was doing something that had never been done before. If you spent your days playing Quake, Final Fantasy VII‘s battle graphics probably weren’t going to impress you overmuch; if you knew, say, Toonstruck, even the cut scenes might strike you as pretty crude. And then, too, computer-based adventure games and RPGs had been delivering well-developed long-form interactive narratives for many years by 1997, most recently with a decidedly cinematic bent more often than not, with voice actors in place of Final Fantasy VII‘s endless text boxes. Wasn’t Final Fantasy VII just a case of console gamers belatedly catching on to something computer gamers had known all along, and being forced to do so in a technically inferior fashion at that?

Well, yes and no. It’s abundantly true that much of what struck so many as so revelatory about Final Fantasy VII really wasn’t anywhere near as novel as they thought it was. At the same time, though, the aesthetic and design philosophies which it applied to the abstract idea of the RPG truly were dramatically different from the set of approaches favored by Western studios. They were so different, in fact, that the RPG genre in general would be forever bifurcated in gamers’ minds going forward, as the notion of the “JRPG” — the Japanese RPG — entered the gaming lexicon. In time, the label would be applied to games that didn’t actually come from Japan at all, but that evinced the set of styles and approaches so irrevocably cemented in the Western consciousness under the label of “Japanese” by Final Fantasy VII.

We might draw a parallel with what happened in music in the 1960s. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and all the other Limey bands who mounted the so-called “British Invasion” of their former Colonies in 1964 had all spent their adolescence steeped in American rock and roll. They took those influences, applied their own British twist to them, then sold them back to American teenagers, who screamed and fainted in the concert halls like Final Fantasy VII fans later would in the pages of the gaming magazines, convinced that the rapture they were feeling was brought on by something genuinely new under the sun — which in the aggregate it was, of course. It took the Japanese to teach Americans how thrilling and accessible — even how emotionally moving — the gaming genre they had invented could truly be.

The roots of the JRPG can be traced back not just to the United States but to a very specific place and time there: to the American Midwest in the early 1970s, where and when Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, a pair of stolid grognards who would have been utterly nonplussed by the emotional histrionics of a Final Fantasy VII, created a “single-unit wargame” called Dungeons & Dragons. I wrote quite some years ago on this site that their game’s “impact on the culture at large has been, for better or for worse, greater than that of any single novel, film, or piece of music to appear during its lifetime.” I almost want to dismiss those words now as the naïve hyperbole of a younger self. But the thing is, I can’t; I have no choice but to stand by them. Dungeons & Dragons really was that earthshaking, not only in the obvious ways — it’s hard to imagine the post-millennial craze for fantasy in mass media, from the Lord of the Rings films to Game of Thrones, ever taking hold without it — but also in subtler yet ultimately more important ones, in the way it changed the role we play in our entertainments from that of passive spectators to active co-creators, making interactivity the watchword of an entire age of media.

The early popularity of Dungeons & Dragons coincided with the rise of accessible computing, and this proved a potent combination. Fans of the game with access to PLATO, a groundbreaking online community rooted in American universities, moved it as best they could onto computers, yielding the world’s first recognizable CRPGs. Then a couple of PLATO users named Robert Woodhead and Andrew Greenberg made a game of this type for the Apple II personal computer in 1981, calling it Wizardry. Meanwhile Richard Garriott was making Ultima, a different take on the same broad concept of “Dungeons & Dragons on a personal computer.”

By the time Final Fantasy VII stormed the gates of the American market so triumphantly in 1997, the cultures of gaming in the United States and Japan had diverged so markedly that one could almost believe they had never had much of anything to do with one another. Yet in these earliest days of digital gaming — long before the likes of the Nintendo Entertainment System, when Japanese games meant only coin-op arcade hits like Space Invaders, Pac-Man, and Donkey Kong in the minds of most Americans — there was in fact considerable cross-pollination. For Japan was the second place in the world after North America where reasonably usable, pre-assembled, consumer-grade personal computers could be readily purchased; the Japanese Sharp MZ80K and Hitachi MB-6880 trailed the American Trinity of 1977 — the Radio Shack TRS-80, Apple II, and Commodore PET — by less than a year. If these two formative cultures of computing didn’t talk to one another, whom else could they talk to?

Thus pioneering American games publishers like Sierra On-Line and Brøderbund forged links with counterparts in Japan. A Japanese company known as Starcraft became the world’s first gaming localizer, specializing in porting American games to Japanese computers and translating their text into Japanese for the domestic market. As late as the summer of 1985, Roe R. Adams III could write in Computer Gaming World that Sierra’s sprawling twelve-disk-side adventure game Time Zone, long since written off at home as a misbegotten white elephant, “is still high on the charts after three years” in Japan. Brøderbund’s platformer Lode Runner was even bigger, having swum like a salmon upstream in Japan, being ported from home computers to coin-op arcade machines rather than the usual reverse. It had even spawned the world’s first e-sports league, whose matches were shown on Japanese television.

At that time, the first Wizardry game and the second and third Ultima had only recently been translated and released in Japan. And yet if Adams was to be believed,[1]Adams was not an entirely disinterested observer. He was already working with Robert Woodhead on Wizardry IV, and had in fact accompanied him to Japan in this capacity. both games already

have huge followings. The computer magazines cover Lord British [Richard Garriott’s nom de plume] like our National Inquirer would cover a television star. When Robert Woodhead of Wizardry fame was recently in Japan, he was practically mobbed by autograph seekers. Just introducing himself in a computer store would start a near-stampede as people would run outside to shout that he was inside.

The Wizardry and Ultima pump had been primed in Japan by a game called The Black Onyx, created the year before in their image for the Japanese market by an American named Henk Rogers.[2]A man with an international perspective if ever there was one, Rogers would later go on to fame and fortune as the man who brought Tetris out of the Soviet Union. But his game was quickly eclipsed by the real deals that came directly out of the United States.

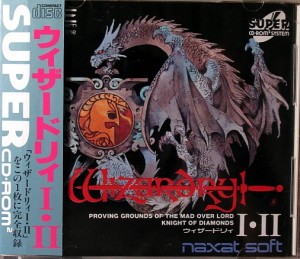

Wizardry in particular became a smashing success in Japan, even as a rather lackadaisical attitude toward formal and audiovisual innovation on the part of its masterminds was already condemning it to also-ran status against Ultima and its ilk in the United States. It undoubtedly helped that Wizardry was published in Japan by ASCII Corporation, that country’s nearest equivalent to Microsoft, with heaps of marketing clout and distributional muscle to bring to bear on any challenge. So, while the Wizardry series that American gamers knew petered out in somewhat anticlimactic fashion in the early 1990s after seven games,[3]It would be briefly revived for one final game, the appropriately named Wizardry 8, in 2001. it spawned close to a dozen Japanese-exclusive titles later in that decade alone, plus many more after the millennium, such that the franchise remains to this day far better known by everyday gamers in Japan than it is in the United States. Robert Woodhead himself spent two years in Japan in the early 1990s working on what would have been a Wizardry MMORPG, if it hadn’t proved to be just too big a mouthful for the hardware and telecommunications infrastructure at his disposal.

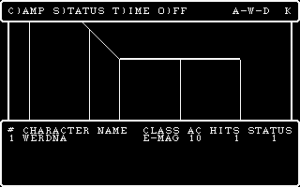

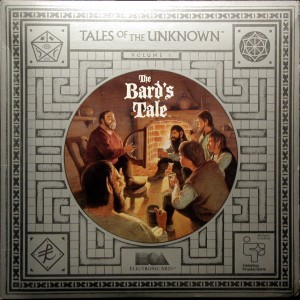

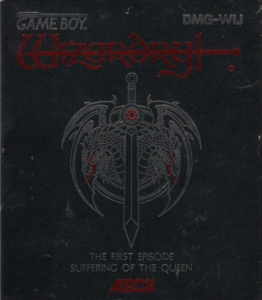

Box art helps to demonstrate Wizardry‘s uncanny legacy in Japan. Here we see the original 1981 American release of the first game.

And here we have a Japan-only Wizardry from a decade later, self-consciously echoing a foreboding, austere aesthetic that had become more iconic in Japan than it had ever been in its home country. (American Wizardry boxes from the period look nothing like this, being illustrated in a more conventional, colorful epic-fantasy style.)

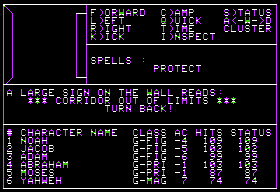

Much of the story of such cultural exchanges inevitably becomes a tale of translation. In its original incarnation, the first Wizardry game had had the merest wisp of a plot. In this as in all other respects it was a classic hack-and-slash dungeon crawler: work your way down through ten dungeon levels and kill the evil wizard, finito. What background context there was tended to be tongue-in-cheek, more Piers Anthony than J.R.R. Tolkien; the most desirable sword in the game was called the “Blade of Cuisinart,” for Pete’s sake. Wizardry‘s Japanese translators, however, took it all in with wide-eyed earnestness, missing the winking and nodding entirely. They saw a rather grim, austere milieu a million miles away from the game that Americans knew — a place where a Cuisinart wasn’t a stainless-steel food processor but a portentous ancient warrior clan.

When the Japanese started to make their own Wizardry games, they continued in this direction, to almost hilarious effect if one knew the source material behind their efforts; it rather smacks of the post-apocalyptic monks in A Canticle for Liebowitz making a theology for themselves out of the ephemeral advertising copy of their pre-apocalyptic forebears. A franchise that had in its first several American releases aspired to be about nothing more than killing monsters for loot — and many of them aggressively silly monsters at that — gave birth to audio CDs full of po-faced stories and lore, anime films and manga books, a sprawling line of toys and miniature figures, even a complete tabletop RPG system. But, lest we Westerners begin to feel too smug about all this, know that the same process would eventually come to work in reverse in the JRPG field, with nuanced Japanese writing being flattened out and flat-out misunderstood by clueless American translators.

The history of Wizardry in Japan is fascinating by dint of its sheer unlikeliness, but the game’s importance on the global stage actually stems more from the Japanese games it influenced than from the ones that bore the Wizardry name right there on the box. For Wizardry, along with the early Ultima games, happened to catch the attention of Koichi Nakamura and Yuji Horii, a software-development duo who had already made several games together for a Japanese publisher called Enix. “Horii-san was really into Ultima, and I was really into Wizardry,” remembers Nakamura. This made sense. Nakamura was the programmer of the pair, naturally attracted to Wizardry‘s emphasis on tactics and systems. Horii, on the other hand, was the storytelling type, who wrote for manga magazines in addition to games, and was thus drawn to Ultima‘s quirkier, more sprawling world and its spirit of open-ended exploration. The pair decided to make their own RPG for the Japanese market, combining what they each saw as the best parts of Wizardry and Ultima.

Yuji Horii in the 1980s. Little known outside his home country, he is a celebrity inside its borders. In his book on Japanese videogame culture, Chris Kohler calls him a Steven Spielberg-like figure there, in terms both of name recognition and the style of entertainment he represents.

This was interesting, but not revolutionary in itself; you’ll remember that Henk Rogers had already done essentially the same thing in Japan with The Black Onyx before Wizardry and Ultima ever officially arrived there. Nevertheless, the choices Nakamura and Horii made as they set about their task give them a better claim to the title of revolutionaries on this front than Rogers enjoys. They decided that making a game that combined the best of Wizardry and Ultima really did mean just that: it did not mean, that is to say, throwing together every feature of each which they could pack in and calling it a day, as many a Western developer might have. They decided to make a game that was simpler than either of its inspirations, much less the two of them together.

Their reasons for doing so were artistic, commercial, and technical. In the realm of the first, Horii in particular just didn’t like overly complicated games; he was the kind of player who would prefer never to have to glance at a manual, whose ideal game intuitively communicated to you everything you needed to know in order to play it. In the realm of the second, the pair was sure that the average Japanese person, like the average person in most countries, felt the same as Horii; even in the United States, Ultima and Wizardry were niche products, and Nakamura and Horii had mass-market ambitions. And in the realm of the third, they were sharply limited in how much they could put into their RPG anyway, because they intended it for the Nintendo Famicom console, where their entire game — code, data, graphics, and sound — would have to fit onto a 64 K cartridge in lieu of floppy disks and would have to be steerable using an eight-button controller in lieu of a keyboard. Luckily, Nakamura and Horii already had experience with just this sort of simplification. Their most recent output had been inspired by the adventure games of American companies like Sierra and Infocom, but had replaced those games’ text parsers with controller-friendly multiple-choice menus.

In deciding to put American RPGs through the same wringer, they established one of the core attributes of the JRPG sub-genre: generally speaking, these games were and would remain simpler than their Western counterparts, which sometimes seemed to positively revel in their complexity as a badge of honor. Another attribute emerged fully-formed from the writerly heart of Yuji Horii. He crafted an unusually rich, largely linear plot for the game. Rather than being a disadvantage, he thought linearity would make this new style of console game “more accessible to consumers”: “We really focused on ensuring people would be able to experience the fun of the story.”

He called upon his friends at the manga magazines to help him illustrate his tale with large, colorful figures in that distinctly Japanese style that has become so immediately recognizable all over the world. At this stage, it was perhaps more prevalent on the box than in the game itself, the Famicom’s graphical fidelity being what it was. Nonetheless, another precedent that has held true in JRPGs right down to the present day was set by the overall visual aesthetic of this, the canonical first example of the breed. Ditto its audio aesthetic, which took the form of a memorable, melodic, eminently hummable chip-tune soundtrack. “From the very beginning, we wanted to create a warm, inviting world,” says Horii.

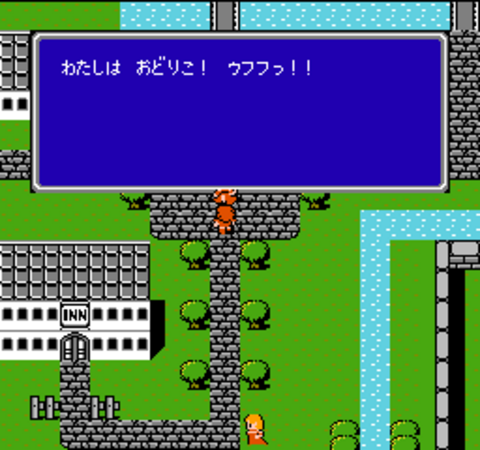

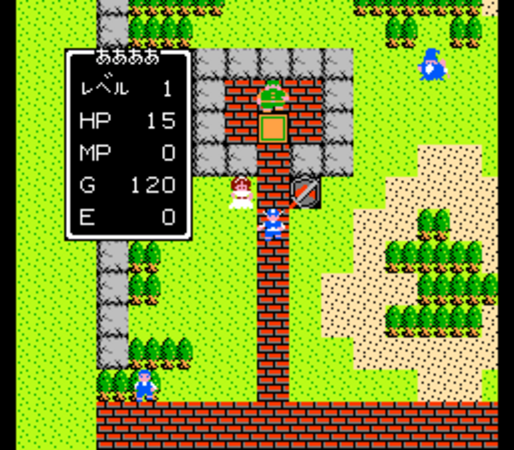

Dragon Quest. Ultima veterans will almost expect to meet Lord British on his throne somewhere. With its overhead view and its large over-world full of towns to be visited, Dragon Quest owed even more to Ultima than it did to Wizardry — unsurprisingly so, given that the former was the American RPG which its chief creative architect Yuji Horii preferred.

Dragon Quest was released on May 27, 1986. Console gamers — not only those in Japan, but anywhere on the globe — had never seen anything like it. Playing this game to the end was a long-form endeavor that could stretch out over weeks or months; you wrote down an alphanumeric code it provided to you on exit, then entered this code when you returned to the game in order to jump back to wherever you had left off.

That said, the fact that the entire game state could be packed into a handful of numbers and letters does serve to illustrate just how simple Dragon Quest really was at bottom. By the standards of only a few years later, much less today, it was pretty boring. Fighting random monsters wasn’t so much a distraction from the rest of the game as the only thing available to do; the grinding was the game. In 2012, critic Nick Simberg wondered at “how willing we were to sit down on the couch and fight the same ten enemies over and over for hours, just building up gold and experience points”; he compared Dragon Quest to “a child’s first crayon drawing, stuck with a magnet to the fridge.”

And yet, as the saying goes, you have to start somewhere. Japanese gamers were amazed and entranced, buying 1 million copies of Dragon Quest in its first six months, over 2 million copies in all. And so a new sub-genre was born, inspired by American games but indelibly Japanese in a way The Black Onyx had not been. Many or most of the people who played and enjoyed Dragon Quest had never even heard of its original wellspring Dungeons & Dragons.

We all know what happens when a game becomes a hit on the scale of Dragon Quest. There were sequels — two within two years of the first game, then three more in the eight years after them, as the demands of higher production values slowed down Enix’s pace a bit. Wizardry was big in Japan, but it was nothing compared to Dragon Quest, which sold 2.4 million copies in its second incarnation, followed by an extraordinary 3.8 million copies in its third. Middle managers and schoolmasters alike learned to dread the release of a new entry in the franchise, as about half the population of Japan under a certain age would invariably call in sick that day. When Enix started bringing out the latest games on non-business days, a widespread urban legend said this had been done in accordance with a decree from the Japanese Diet, which demanded that “henceforth Dragon Quest games are to be released on Sunday or national holidays only”; the urban legend wasn’t true, but the fact that so many people in Japan could so easily believe it says something in itself. Just as the early American game Adventure lent its name to an entire genre that followed it, the Japanese portmanteau word for “Dragon Quest” — Dorakue — became synonymous with the RPG in general there, such that when you told someone you were “playing dorakue” you might really be playing one of the series’s countless imitators.

Giving any remotely complete overview of these dorakue games would require dozens of articles, along with someone to write them who knows far more about them than I do. But one name is inescapable in the field. I refer, of course, to Final Fantasy.

Legend has it that Hironobu Sakaguchi, the father of Final Fantasy, chose that name because he thought that the first entry in the eventual franchise would be the last videogame he ever made. A former professional musician with numerous and diverse interests, Sakaguchi had been working for the Japanese software developer and publisher Square for a few years already by 1987, designing and programming Famicom action games that he himself found rather banal and that weren’t even selling all that well. He felt ready to do something else with his life, was poised to go back to university to try to figure out what that thing ought to be. But before he did so, he wanted to try something completely different at Square.

Another, less dramatic but probably more accurate version of the origin story has it that Sakaguchi simply liked the way the words “final’ and “fantasy” sounded together. At any rate, he convinced his managers to give him half a dozen assistants and six months to make a dorakue game.[4]In another unexpected link between East and West, one of his most important assistants became Nasir Gebelli, an Iranian who had fled his country’s revolution for the United States in 1979 and become a game-programming rock star on the Apple II. After the heyday of the lone-wolf bedroom auteur began to fade there, Doug Carlston, the head of Brøderbund, brokered a job for him with his friends in Japan. There he maximized the Famicom’s potential in the same way he had that of the Apple II, despite not speaking a word of Japanese when he arrived. (“We’d go to a restaurant and no matter what he’d order — spaghetti or eggs — they’d always bring out steak,” Sakaguchi laughs.) Gebelli would program the first three Final Fantasy games almost all by himself.

The very first Final Fantasy may not have looked all that different from Dragon Quest at first glance — it was still a Famicom game, after all, with all the audiovisual limitations that implies — but it had a story line that was more thematically thorny and logistically twisted than anything Yuji Horii might have come up with. As it began, you found yourself in the midst of a quest to save a princess from an evil knight, which certainly sounded typical enough to anyone who had ever played a dorakue game before. In this case, however, you completed that task within an hour, only to learn that it was just a prologue to the real plot. In his book-length history and study of the aesthetics of Japanese videogames, Chris Kohler detects an implicit message here: “Final Fantasy is about much more than saving the princess. Compared to the adventure that is about to take place, saving a princess is merely child’s play.” In fact, only after the prologue was complete did the opening credits finally roll, thus displaying another consistent quality of Final Fantasy: its love of unabashedly cinematic drama.

Still, for all that it was more narratively ambitious than what had come before, the first Final Fantasy can, like the first Dragon Quest, seem a stunted creation today. Technical limitations meant that you still spent 95 percent of your time just grinding for experience. “Final Fantasy may have helped build the genre, but it didn’t necessarily know exactly how to make it fun,” acknowledges Aidan Moher in his book about JRPGs. And yet when it came to dorakue games in the late 1980s, it seemed that Sakaguchi’s countrymen were happy to reward even the potential for eventual fun. They made Final Fantasy the solid commercial success that had heretofore hovered so frustratingly out of reach of its creator; it sold 400,000 copies. Assured that he would never have to work on a mindless action game again, Sakaguchi agreed to stay on at Square to build upon its template.

Final Fantasy II, which was released exactly one year after the first game in December of 1988 and promptly doubled its sales, added more essential pieces to what would become the franchise’s template. Although labelled and marketed as a sequel, its setting, characters, and plot had no relation to what had come before. Going forward, it would remain a consistent point of pride with Sakaguchi to come up with each new Final Fantasy from whole cloth, even when fans begged him for a reunion with their favorite places and people. In a world afflicted with the sequelitis that ours is, he can only be commended for sticking to his guns.

In another sense, though, Final Fantasy II was notable for abandoning a blank slate rather than embracing it. For the first time, its players were given a pre-made party full of pre-made personalities to guide rather than being allowed to roll their own. Although they could rename the characters if they were absolutely determined to do so — this ability would be retained as a sort of vestigial feature as late as Final Fantasy VII — they were otherwise set in stone, the better to serve the needs of the set-piece story Sakaguchi wanted to tell. This approach, which many players of Western RPGs did and still do regard as a betrayal of one of the core promises of the genre, would become commonplace in JRPGs. Few contrasts illustrate so perfectly the growing divide between these two visions of the RPG: the one open-ended and player-driven, sometimes to a fault; the other tightly scripted and story-driven, again sometimes to a fault. In a Western RPG, you write a story for yourself; in a JRPG, you live a story that someone else has already written for you.

Consider, for example, the two lineage’s handling of mortality. If one of your characters dies in battle in a Western RPG, it might be difficult and expensive, or in some cases impossible, to restore her to life; in this case, you either revert to an earlier saved state or you just accept her death as another part of the story you’re writing and move on to the next chapter with an appropriately heavy heart. In a JRPG, on the other hand, death in battle is never final; it’s almost always easy to bring a character who gets beat down to zero hit points back to life. What are truly fatal, however, are pre-scripted deaths, the ones the writers have deemed necessary for storytelling purposes. Final Fantasy II already contained the first of these; years later, Final Fantasy VII would be host to the most famous of them all, a death so shocking that you just have to call it that scene and everyone who has ever played the game will immediately know what you’re talking about. To steal a phrase from Graham Nelson, the narrative always trumps the crossword in JRPGs; they happily override their gameplay mechanics whenever the story they wish to tell demands it, creating an artistic and systemic discontinuity that’s enough to make Aristotle roll over in his grave. Yet a huge global audience of players are not bothered at all by it — not if the story is good enough.

But we’ve gotten somewhat ahead of ourselves; the evolution of the 1980s JRPG toward the modern-day template came in fits and starts rather than a linear progression. Final Fantasy III, which was released in 1990, actually returned to a player-generated party, and yet the market failed to punish it for its conservatism. Far from it: it sold 1.4 million copies.

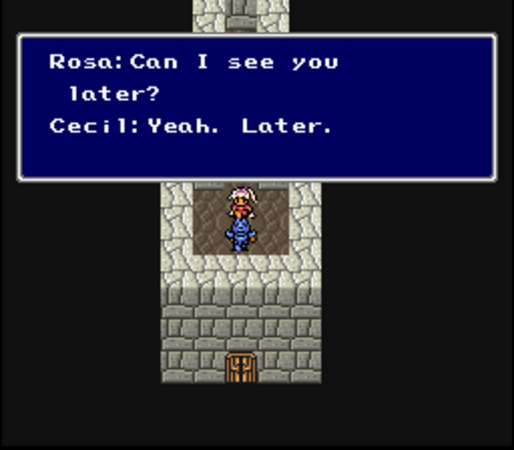

Final Fantasy IV, on the other hand, chose to double down on the innovations Final Fantasy II had deployed, and sold in about the same numbers as Final Fantasy III. Released in July of 1991, it provided you with not just a single pre-made party but an array of characters who moved in and out of your control as the needs of the plot dictated, thereby setting yet another longstanding precedent for the series going forward. Ditto the nature of the plot, which leaned into shades of gray as never before. Chris Kohler:

The story deals with mature themes and complex characters. In Final Fantasy II, the squeaky-clean main characters were attacked by purely evil dark knights; here, our main character is a dark knight struggling with his position, paid to kill innocents, trying to reconcile loyalty to his kingdom with his sense of right and wrong. He is involved in a sexual relationship. His final mission for the king turns out to be a mass murder: the “phantom monsters” are really just a town of peaceful humans whose magic the corrupt king has deemed dangerous. (Note the heavy political overtones.)

Among Western RPGs, only the more recent Ultima games had dared to deviate so markedly from the absolute-good-versus-absolute-evil tales of everyday heroic fantasy. (In fact, the plot of Final Fantasy IV bears a lot of similarities to that of Ultima V…)

Ever since Final Fantasy IV, the series has been filled with an inordinate number of moody young James Deans and long-suffering Natalie Woods who love them.

Final Fantasy IV was also notable for introducing an “active-time battle system,” a hybrid between the turn-based systems the series had previously employed and real-time combat, designed to provide some of the excitement of the latter without completely sacrificing the tactical affordances of the former. (In a nutshell, if you spend too long deciding what to do when it’s your turn, the enemies will jump in and take another turn of their own while you dilly-dally.) It too would remain a staple of the franchise for many installments to come.

Final Fantasy V, which was released in December of 1992, was like Final Fantasy III something of a placeholder or even a retrenchment, dialing back on several of the fourth game’s innovations. It sold almost 2.5 million copies.

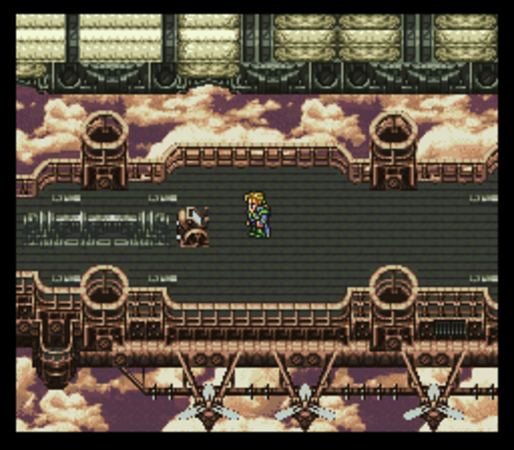

Both the fourth and fifth games had been made for the Super Famicom, Nintendo’s 16-bit successor to its first console, and sported correspondingly improved production values. But most JRPG fans agree that it was with the sixth game — the last for the Super Famicom — that all the pieces finally came together into a truly friction-less whole. Indeed, a substantial and vocal minority will tell you that Final Fantasy VI rather than its immediate successor is the best Final Fantasy ever, balanced perfectly between where the series had been and where it was going.

Final Fantasy VI abandoned conventional epic-fantasy settings for a steampunk milieu out of Jules Verne. As we’ll see in a later article, Final Fantasy VII‘s setting would deviate even more from the norm. This creative restlessness is one of the series’s best traits, standing it in good stead in comparison to the glut of nearly indistinguishably Tolkienesque Western RPGs of the 1980s and 1990s.

From its ominous opening-credits sequence on, Final Fantasy VI strained for a gravitas that no previous JRPG had approached, and arguably succeeded in achieving it at least intermittently. It played out on a scale that had never been seen before; by the end of the game, more than a dozen separate characters had moved in and out of your party. Chris Kohler identifies the game’s main theme as “love in all its forms — romantic love, parental love, sibling love, and platonic love. Sakaguchi asks the player, what is love and where can we find it?”

Before that scene in Final Fantasy VII, Hironobu Sakaguchi served up a shocker of equal magnitude in Final Fantasy VI. Halfway through the game, the bad guys win despite your best efforts and the world effectively ends, leaving your party wandering through a post-apocalyptic World of Ruin like the characters in a Harlan Ellison story. The effect this had on some players’ emotions could verge on traumatizing — heady stuff for a videogame on a console still best known worldwide as the cuddly home of Super Mario. For many of its young players, Final Fantasy VI was their first close encounter on their own recognizance — i.e., outside of compulsory school assignments — with the sort of literature that attempts to move beyond tropes to truly, thoughtfully engage with the human condition.

It’s easy for an old, reasonably well-read guy like me to mock Final Fantasy VI‘s highfalutin aspirations, given that they’re stuffed into a game that still resolves at the granular level into bobble-headed figures fighting cartoon monsters. And it’s equally easy to scoff at the heavy-handed emotional manipulation that has always been part and parcel of the JRPG; subtle the sub-genre most definitely is not. Nonetheless, meaningful literature is where you find it, and the empathy it engenders can only be welcomed in a world in desperate need of it. Whatever else you can say about Final Fantasy and most of its JRPG cousins, the messages these games convey are generally noble ones, about friendship, loyalty, and the necessity of trying to do the right thing in hard situations, even when it isn’t so easy to even figure out what the right thing is. While these messages are accompanied by plenty of violence in the abstract, it is indeed abstracted — highly stylized and, what with the bifurcation between game and story that is so prevalent in the sub-genre, often oddly divorced from the games’ core themes.

Released in April of 1994, Final Fantasy VI sold 2.6 million copies in Japan. By this point the domestic popularity of the Final Fantasy franchise as a whole was rivaled only by that of Super Mario and Dragon Quest; two of the three biggest gaming franchises in Japan, that is to say, were dorakue games. In the Western world, however, the picture was quite different.

In the United States, the first-generation Nintendo Famicom was known as the Nintendo Entertainment System, the juggernaut of a console that rescued videogames in the eyes of the wider culture from the status of a brief-lived fad to that of a long-lived entertainment staple, on par with movies in terms of economics if not cachet. Yet JRPGs weren’t a part of that initial success story. The first example of the breed didn’t even reach American shores until 1989. It was, appropriately enough, the original Dragon Quest, the game that had started it all in Japan; it was renamed Dragon Warrior for the American market, due to a conflict with an old American tabletop RPG by the name of Dragonquest whose trademarks had been acquired by the notoriously litigious TSR of Dungeons & Dragons fame. Enix did make some efforts to modernize the game, such as replacing the password-based saving system with a battery that let you save your state to the cartridge itself. (This same method had been adopted by Final Fantasy and most other post-Dragon Quest JRPGs on the Japanese market as well.) But American console gamers had no real frame of reference for Dragon Warrior, and even the marketing geniuses of Nintendo, which published the game itself in North America, struggled to provide them one. With cartridges piling up in Stateside warehouses, they were reduced to giving away hundreds of thousands of copies of Dragon Warrior to the subscribers of Nintendo Power magazine. For some of these, the game came as a revelation seven years before Final Fantasy VII; for most, it was an inscrutable curiosity that was quickly tossed aside.

Final Fantasy I, on the other hand, received a more encouraging reception in the United States when it reached there in 1990: it sold 700,000 copies, 300,000 more than it had managed in Japan. Nevertheless, with the 8-bit Nintendo console reaching the end of its lifespan, Square didn’t bother to export the next two games in the series. It did export Final Fantasy IV for the Super Famicom — or rather the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, as it was known in the West. The results were disappointing in light of the previous game’s reception, so much so that Square didn’t export Final Fantasy V.[5]Square did release a few spinoff games under the Final Fantasy label in the United States and Europe as another way of testing the Western market: Final Fantasy Legend and Final Fantasy Adventure for the Nintendo Game Boy handheld console, and Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest for the Super Nintendo. Although none of them were huge sellers, the Game Boy titles in particular have their fans even today. This habit of skipping over parts of the series led to a confusing state of affairs whereby the American Final Fantasy II was the Japanese Final Fantasy IV and the American Final Fantasy III was the Japanese Final Fantasy VI. The latter game shifted barely one-fourth as many copies in the three-times larger American marketplace as it had in Japan — not disastrous numbers, but still less than the first Final Fantasy had managed.

The heart of the problem was translation, in both the literal sense of the words on the screen and a broader cultural sense. Believing with some justification that the early American consoles from Atari and others had been undone by a glut of substandard product, Nintendo had long made a science out of the polishing of gameplay, demanding that every prospective release survive an unrelenting testing gauntlet before it was granted the “Nintendo Seal of Quality” and approved for sale. But the company had no experience or expertise in polishing text to a similar degree. In most cases, this didn’t matter; most Nintendo games contained very little text anyway. But RPGs were the exception. The increasingly intricate story lines which JRPGs were embracing by the early 1990s demanded good translations by native speakers. What many of them actually got was something very different, leaving even those American gamers who wanted to fall in love baffled by the Japanese-English-dictionary-derived word salads they saw before them. And then, too, many of the games’ cultural concerns and references were distinctly Japanese, such that even a perfect translation might have left Americans confused. It was, one might say, the Blade of Cuisinart problem in reverse.

To be sure, there were Americans who found all of the barriers to entry into these deeply foreign worlds to be more bracing than intimidating, who took on the challenge of meeting the games on their own terms, often emerging with a lifelong passion for all things Japanese. At this stage, though, they were the distinct minority. In Japan and the United States alike, the conventional wisdom through the mid-1990s was that JRPGs didn’t and couldn’t sell well overseas; this was regarded as a fact of life as fundamental as the vagaries of climate. (Thanks to this belief, none of the mainline Final Fantasy games to date had been released in Europe at all.) It would take Final Fantasy VII and a dramatic, controversial switch of platforms on the part of Square to change that. But once those things happened… look out. The JRPG would conquer the world yet.

Where to Get It: Remastered and newly translated versions of the Japanese Final Fantasy I, II, III, IV, V, and VI are available on Steam. The Dragon Quest series has been converted to iOS and Android apps, just a search away on the Apple and Google stores.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books Pure Invention: How Japan Made the Modern World by Matt Alt, Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life by Chris Kohler, Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West by Aidan Moher, and Atari to Zelda: Japan’s Videogames in Global Contexts by Mia Consalvo. GameFan of September 1997; Retro Gamer 69, 108, and 170; Computer Gaming World of September 1985 and December 1992.

Online sources include Polygon‘s authoritative “Final Fantasy 7: An Oral History”; “The Long Life of the Original Wizardry“ by guest poster Alex on The CRPG Addict blog; “Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook” by Sam Derboo at Hardcore Gaming 101, plus an interview Robert Woodhead, conducted by Jared Petty at the same site; “Wizardry‘s Wild Ride from West to East” at VentureBeat; “The Secret History of AnimEigo” at that company’s homepage; Robert Woodhead’s slides from a presentation at the 2022 KansasFest Apple II convention; a post on tabletop Wizardry at the Japanese Tabletop RPG blog; and “Dragon Warrior: Aging Disgracefully” by Nick Simberg at (the now-defunct) DamnLag.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Adams was not an entirely disinterested observer. He was already working with Robert Woodhead on Wizardry IV, and had in fact accompanied him to Japan in this capacity. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A man with an international perspective if ever there was one, Rogers would later go on to fame and fortune as the man who brought Tetris out of the Soviet Union. |

| ↑3 | It would be briefly revived for one final game, the appropriately named Wizardry 8, in 2001. |

| ↑4 | In another unexpected link between East and West, one of his most important assistants became Nasir Gebelli, an Iranian who had fled his country’s revolution for the United States in 1979 and become a game-programming rock star on the Apple II. After the heyday of the lone-wolf bedroom auteur began to fade there, Doug Carlston, the head of Brøderbund, brokered a job for him with his friends in Japan. There he maximized the Famicom’s potential in the same way he had that of the Apple II, despite not speaking a word of Japanese when he arrived. (“We’d go to a restaurant and no matter what he’d order — spaghetti or eggs — they’d always bring out steak,” Sakaguchi laughs.) Gebelli would program the first three Final Fantasy games almost all by himself. |

| ↑5 | Square did release a few spinoff games under the Final Fantasy label in the United States and Europe as another way of testing the Western market: Final Fantasy Legend and Final Fantasy Adventure for the Nintendo Game Boy handheld console, and Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest for the Super Nintendo. Although none of them were huge sellers, the Game Boy titles in particular have their fans even today. |