One day in 1979 Antonio Antiochia visited Eastern Michigan University with his father, who taught classes there on statistics and computers. Dad had some meetings to take, so he left Antonio in an empty computer lab, one of the few at the university equipped with real video terminals in lieu of the more common teletypes. The terminals were cool, but this was otherwise not an unusual scenario. Antonio had been hanging out at his father’s workplace for the past five years now, tinkering with the various big computers there. Now 13 years old, he could already program fairly well in FORTRAN and operate a keypunch machine. Indeed, he was all too familiar with the traditional method of mainframe programming — deliver a stack of cards to a friendly computer operator, then wait for the printed results. He had even spent many months working on a game. Called Terroron, it was an homage to the Japanese monster movies he loved; the player got to control a monster rampaging through a city. (From the great-minds-think-alike department: this is also the theme of Crush, Crumble, and Chomp!, arguably the most inspired use of the Automated Simulations DunjonQuest engine, as well as the later, more refined The Movie Monster Game.)

So, Antonio knew pretty well what he was doing as he started poking at one of the terminals to see what was what. He didn’t have an account on this system, but found that as Guest he had access to games. Not bad! Inside he found mostly the usual suspects, from Tic Tac Toe to The Oregon Trail. But wait, here was something new… something called ADVENT. He started the program, and was greeted with the text that launched a thousand careers and a million obsessions:

YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING. AROUND YOU IS A FOREST. A SMALL STREAM FLOWS OUT OF THE BUILDING AND DOWN A GULLY.

Antonio didn’t know quite what he was supposed to do next; for some reason this build of the game was missing the usual offer of instructions at the beginning. He flailed at it for a while and gave up. But it continued to tickle at the back of his mind, and a month or so later he tried again. This time he managed to find his way underground, and from there he was hooked. Terroron was quickly forgotten.

But when he finished Adventure at last, he had no more adventure games to play. It was the only one of its type on the university’s computers, and his family had no computer at home as yet. And he lacked the skill to make one of his own; working with text in FORTRAN was notoriously difficult. So, he used his imagination:

I came up with dozens of adventure plots in my spare time (and a few other games), drawing their outlines, their maps, etc., based on a wide variety of themes (a bit heavy on the fantasy genre) — simply out of the joy of creativity and discovery. It was cool.

Antonio had a particular reason to want to retreat into fantasy at this stage of his life. His mother, with whom he had been very close, had just died of cancer, leaving him and his father alone. The world inside his imaginary adventure games often felt much more welcoming than the real one.

One day Antonio mentioned Adventure to a friend of his from school, who in turn delivered the shocking news that there were a number of such games available on microcomputers, written by a guy named Scott Adams. The same friend told him about the Ann Arbor Community High School Computer Club, which had a collection of PCs available for use by the public for a small fee. Antonio became a regular there, playing the Scott Adams games and, eventually, starting to work on a real one of his own at last, a fantasy game called The Land of Ghaja; his adventure-gaming friend did him the final service of helping him to figure out how to parse text in BASIC. When the club was closed, he fed his addiction by visiting local computer stores and using their machines for as long as they would let him.

Antonio had of course been pestering his father for a computer of his own for months, and at last Dad could resist no longer. He brought home a new Apple II Plus, with the condition that the two would share it. Antonio quickly finished Land of Ghaja. “It was a little bit primitive,” he admits today. Still, he passed the game around his local circle of friends and fellow computer-club members, to a pretty good reception.

With time and privacy for his projects at last thanks to his father’s purchase, he started on another game that would benefit from what he had learned from the first. It would not only be more technically advanced, but would have a more unique setting. He was a big fan of Halloween and of classic movie horror of the Boris Karloff / Bela Lugosi / Lon Chaney, Jr. era. His new game would be horror — but a fun, retro, slightly campy sort of horror, more The Wolfman than the horror sensation of the moment, The Shining. Like one of his favorite movies, Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein, Antonio threw it all in: a werewolf, a vampire, even an alien and his UFO. He eventually named the game Transylvania. Not that he had ever been there or knew much of anything about the real place. His Transylvania was the land of old horror movies and tales and, of course, imagination.

Antonio’s father helped out as editor and coach. An Italian immigrant who spoke English with a strong accent, he nevertheless had an excellent command of English grammar and style, and was a steadfast source of encouragement. Antonio honed the game over a period of several months. Satisfied at last, he passed it among his friends and made plans to start another; the thought of doing anything else with it had yet to enter his mind. His father, meanwhile, had started ordering computer supplies from Mark Pelczarski’s post-SoftSide, pre-Penguin venture Micro Co-op. One day while placing an order over the phone he mentioned that his son had written a really impressive adventure game. Mark said that he was starting a publishing company (“Co-op Software”) to go along with the mail-order business. “Send it to us. We’d like to see it.” From that chance exchange was born the eventual Penguin Software’s first adventure game.

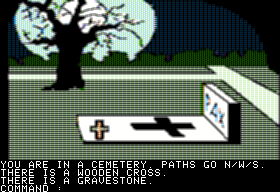

Mark immediately liked the game, but he was also aware that it was getting harder to sell pure text adventures on the Apple II in the wake of On-Line’s Hi-Res Adventure line. And there was something a little bit off about “the leader in Apple II graphics” releasing a game with no graphics. Could Antonio add some pictures? To help him, he was willing to give him all of his latest graphics software, including programs that would eventually become a part of The Graphics Magician, but that hadn’t yet been released at this point (summer 1981). Antonio wasn’t an artist and had no experience with computer graphics, but he was a trouper. While Penguin Software established and consolidated their position as “the graphics people,” Antonio sat at home laboriously drawing picture after picture using the software Mark had provided and the standard pair of paddles that came with every Apple II. Doing so ended up taking much more time than actually writing the game had — some nine months. His patient labor yielded some of the best graphics of the “hi-res adventure” era. (I’ve added a blurring effect to the image below and all of those that follow to try to convey what they would have looked like on a contemporary monitor, where the dithering would have smeared the pixels together to create many more apparent colors than the Apple II’s standard six. Our pixel-perfect digital screens otherwise just can’t do them justice.)

With the graphics done at last, Mark and the others at Penguin stepped in to do the final polishing. They cleaned up the original BASIC code, adding in some assembly-language routines to handle the graphics. And they put the game through considerable playtesting, adding responses to various actions that Antonio hadn’t anticipated. They also had some fun. “Werewolves of London,” the one hit single of the great Warren Zevon, was in heavy rotation at the Penguin offices as they worked on the game. Soon more and more of the song was finding its way into the game. Zevon’s caustic wit would have made an interesting contrast with Antonio’s more innocent monster-movie fixations, but in the end most of the former was edited out again. Messages like “He ripped your lungs out, Jim” just prompted too much confusion (“Who the heck is Jim?”) from people who didn’t know the song. Only one fragment remains in the released version.

The game that finally emerged from Penguin that summer of 1982 is one of the most charming of its genre and era. Yes, its parser and world model are extremely primitive in comparison to the contemporary games of Infocom. Yet it plays within its formal limitations beautifully. In fact, it’s an almost uniquely playable example of its type, thanks both to a lots of addition by subtraction — no maze, no guess-the-verb puzzles — and, well, lots of addition by addition: a collection of simple object-based puzzles that are commonsensical and play smartly within the strict limits set by the game’s technical underpinnings. The design as a whole is unusually open, crafted in a way that usually gives you lots of puzzles to work on in whatever order you choose. As Mark Pelczarski wrote in an email to me:

With Transylvania you could wander from puzzle to puzzle and see much of the Transylvania universe without getting stuck. At most points in the game there were maybe 3-5 or more open puzzles to solve. Each led you further into the game, but seldom was one single puzzle a sticking point or roadblock (until you solved all the others).

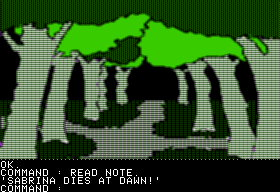

Given this level of non-linearity and the limited amount of text in the game, Transylvania is inevitably more of a pastiche of fragments taken from other fictions than a coherent narrative experience of its own. Early on we find a note which tells us in all of four words everything we need to know about the plot: that a Princess Sabrina is going to be killed at dawn (Ach! A time limit!) and that it’s up to us to rescue her.

A pastiche it may be, but Transylvania absolutely nails the half Gothic, half campy atmosphere of a classic Universal monster movie. And anyway, by the time they got to the 1940s and the likes of Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman or Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein, the Universal films were themselves little more than mix-and-match pastiches.

Like those movies, Transylvania has its chills, especially in the wandering werewolf and vampire who can creep up on you at any time, but there’s something almost comfortingly innocent about it all. This is safe horror that never trangresses certain well-understood boundaries.

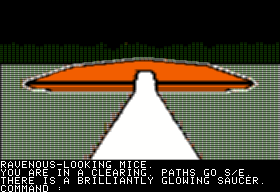

Still, and just to remind us that it was after all written some 30 years after its inspirations went out of fashion, Antonio also threw in a UFO right out of Steven Spielberg.

Antonio told me recently that he had quite a twist on the classic monster movie in mind: that the vampire had actually come on the UFO, was actually an alien. He was “quite proud of myself and thought this was original” in this era before vampires were absolutely everywhere in pop culture, although it’s not something that can really be gleaned from the finished game. He describes the game today as “unsophisticated” but with a “simple playfulness” that makes it “likable.” I couldn’t agree more. Transylvania charmed me in a way akin to Ultima, the issue of another bright, precocious kid who wanted to pack as much cool stuff into his game as possible in the hope that you would like it all as much as he did.

Some time after Transylvania‘s release, and as Antonio was going through the surreal experience of coming home from school to find royalty checks for thousands of dollars in his mailbox, Penguin received a rather unusual package that came from an entire grade-school class in Australia. Its ostensible purpose was to ask for a hint book, but each kid in the class also contributed a crayon drawing inspired by the game. Antonio has kept and cherished the package to this day: “When I go through sad or frustrating times, I will sometimes read through those old letters to cheer myself up.” Indeed, making a class of schoolchildren happy is about as worthy an achievement as there is in life. I spend a lot of time on this blog talking about the progress of the art of ludic narrative and all that, but adventure games are most of all supposed to be fun, and are supposed to make people happy. And Transylvania delivers.

If you want to have some fun of your own, here’s an Apple II disk image of Transylvania. Or those of you with iOS devices can buy a port.

(My sincere thanks to Antonio Antiochia and, once again, to Mark Pelczarski for lending their memories and perspectives to this article.)