‘Tis true my form is something odd,

But blaming me is blaming God;

Could I create myself anew

I would not fail in pleasing you.— poem by Joseph Merrick, “The Elephant Man”

This article does contain some spoilers for Ballyhoo!

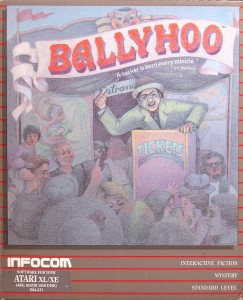

Ballyhoo, a low-key mystery written by a new Implementor, was the last game ever released by an independent Infocom. When it appeared in February of 1986, Al Vezza and Joel Berez were desperately trying to reel in their lifeline of last resort, a competitor interested in acquiring this imploding company that had fallen from such a precipitous height in just a year’s time. Having come in like a lion with Zork, Infocom, Inc., would go out like a lamb with Ballyhoo; it would go on to become one of their least remembered and least remarked games. We’ll eventually get to some very good reasons for Ballyhoo to be regarded as one of the lesser entries in the Infocom canon. Still, it’s also deserving of more critical consideration than it’s generally received for its unique tone and texture and, most importantly, for a very significant formal innovation. In fact, discounting as relative trivialities some small-scale tinkering with abbreviations and the like and as evolutionary dead ends a blizzard of largely unsuccessful experiments that would mark Infocom’s final years, said innovation would be the last such to significantly impact the art of the text adventure as it would evolve after the commercial glory years of the 1980s.

If Ballyhoo is one of Infocom’s more forgotten games, its creator, Jeff O’Neill, is certainly the Forgotten Implementor. His perspective is conspicuously absent from virtually every history written of the company in the last quarter century. Most notably, he was the one Imp who declined to be interviewed for Jason Scott’s Get Lamp project. For reasons that we won’t dwell on here, O’Neill remains deeply embittered by his time with Infocom. Incredible as this may sound to those of us today who persist in viewing the company’s brief life as a sort of Camelot, that time in his own life is one that O’Neill would rather forget, as I learned to my disappointment when I reached out to him before writing this article. He has a right to his silence and his privacy, so we’ll leave it at that and confine ourselves to the public details.

O’Neill, at the time a frustrated young journalist looking for a career change, was hired by Infocom in the spring of 1984, just one of what would prove to be a major second wave of talent — including among their ranks Jon Palace and Brian Moriarty — who arrived at about the same time. Like Moriarty, O’Neill’s original role was a practical one: he became one of Infocom’s in-house testers. Having proved himself by dint of talent and hard work and the great ideas for new games he kept proposing, within about a year he became the first of a few who would eventually advance out of the testing department to become late-period Imps after Infocom’s hopes for hiring outside writers to craft their games proved largely fruitless.

Whether we attribute it to his degree in Journalism or innate talent, O’Neill had one of the most delicate writerly touches to be found amongst the Imps. Ballyhoo adds a color to Infocom’s emotional palette that we haven’t seen before: world-weary melancholy. The setting is a spectacularly original one for any adventurer tired of dragons and spaceships: an anachronistic, down-at-the-heels circus called “The Traveling Circus That Time Forgot, Inc.” The tears behind a clown’s greasepaint facade, as well as the tawdry desperation that is the flip side of “the show must go on” for performers and performances past their time, have been amply explored in other art forms. Yet such subtle shades of feeling have been only rarely evoked by games before or after Ballyhoo. Ballyhoo, in the words of one of its own more memorable descriptive passages, “exposes the underside of circus life — grungy costumes strung about, crooked and cracked mirrors, the musty odor of fresh makeup mingled with clown sweat infusing the air.” Given what was going on around O’Neill as he wrote the game, it feels hard not to draw parallels with Infocom’s own brief ascendency and abrupt fall from grace: “Your experience of the circus, with its ballyhooed promises of wonderment and its ultimate disappointment, has been to sink your teeth into a candy apple whose fruit is rotten.”

The nihilistic emptiness at the heart of the circus sideshow, the tragedy of these grotesques who parade themselves before the public because there’s no other alternative available to them, has likewise been expressed in art stretching at least as far back as Freaks, a 1932 film directed by Tod Browning that’s still as shocking and transgressive as it is moving today. Another obvious cultural touchstone, which would have been particularly fresh in the mid-1980s thanks to Bernard Pomerance’s 1979 play and David Lynch’s 1980 film, is the story of the so-called “Elephant Man”: Joseph Merrick, a gentle soul afflicted with horrendous deformities who was driven out into the street by his father at age 17 and forced to sell himself to various exploiters as a traveling “human curiosity.” Some say that Merrick died at age 27 in 1890 because he insisted on trying to lie down to sleep — something his enormous, misshapen head would not allow — as part of his fruitless lifelong quest just to “be like other people.”

Ballyhoo‘s own collection of freaks is less extreme but can be almost as heartbreaking. There’s Comrade Thumb, the Russian midget who’s been crammed into a Czarist general’s uniform and sent out to do tricks. Like Merrick, whose deformities made speech almost impossible, Thumb can’t even communicate with his fellow humans; he speaks only Russian (I’ve had just a taste of this sort of linguistic isolation at times since leaving the United States, and know how hard it can be). But saddest of all is the case of Tina, the “827 pounds of feminine charm” who’s become the circus’s token fat woman.

>n

West Half of Fat Lady

Dominating this once spacious room, geographic in her enormity, mountainous in her irreducibility, the fat lady sits (though no chair is visible) breathtakingly to the east. Paths around the attraction lead northeast and southeast. The exit is south.

>examine lady

The fat lady is wearing a big top, and the expression on her face is sad and distant, almost Rushmorean. She appears to be holding a small radio up to her ear.

>ne

It's a long haul, the scenery changing little. Eventually you arrive at ...

East Half of Fat Lady

The fat lady sits (though no chair is visible) breathtakingly to the west. Paths around the attraction lead northwest and southwest.

>give granola bar to tina

Tina is quick to confiscate the one-dollar-and-85-cent granola bar from your hand and grinds it up without hesitation. Turning her far-away gaze slowly in your direction, she seems to notice you for the first time this evening.

>tina, hello

She merely sighs wistfully, which creates a gale-force gust, and cranes her wrecking-ball-sized hand over to you.

>take hand

As you take hold, the fat lady's hand becomes relaxed, its full weight now residing in your arms like a sandbag and making your knees buckle.

>shake hand

Though unable to budge the fat lady's hand, your friendly intentions are nevertheless understood. The fat lady appears quite taken by your kindnesses. She clasps both her hands up to her chins, and stares ahead in teary silence.

If these passages, far from politically correct but by no means heartless, make you a bit uncomfortable, well, I like to think that they were meant to. After all, we’re among the sideshow gawkers. I’ve known people like Tina, cut off by their weight or other issues from a normal life, destined always to be noticed but never to be included. I recognize that wistful sigh, that far-off stare, that above-it-all stance that becomes their only defense. As for people like the circus’s manager Mr. Munrab — read the name backward — who we learn elsewhere “orders the roustabout to increase the frequency of her [Tina’s] feeding” every time she tries to go on a diet…. well, I’d like to think there’s a special circle of Hell for him along with Tom Norman, the man who stuck Joseph Merrick in a cage and set it up for the punters on Whitechapel Road.

I don’t want to give the impression that Ballyhoo is all doom and gloom, and certainly not that it’s entirely one-note in its mood. As Tina’s passages show, the game takes place in a vaguely surreal David Lynch-ian realm that’s tethered to but not quite the same as our own reality. This gives ample room for some flights of fancy that don’t always have to make us feel bad. O’Neill’s love of abstract wordplay, the theme around which his second and final work of interactive fiction would be built, also pops up in Ballyhoo from time to time. When you find yourself with an irresistible craving for something sweet, for instance, it takes the form of a literal monkey on your back who drives you to the concession stand. O’Neill also toys with the parser and the player sitting behind it to a degree not seen in an Infocom game since The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Here’s what happens when you come upon a “piece of wood” that turns out to be a mousetrap:

>get wood

You have just encountered that brief instant of time between the realization that you've caused yourself excruciating Pain and the actual onslaught of such Pain, during which time most people speak with exclamation points and ... well, say things like ...

>fuck

Easy there! You're jeopardizing our "G" rating.

>darn

Bravisimo! Once more now, with feeling.

>darn

Cut! Cut! Okay, that's a wrap.

There’s even a fake death message, just the sort of faintly cruel player trickery that would have made Adams proud.

Indeed, there’s a little bit of bite, even a faint note of misanthropy, to O’Neill’s writing that’s largely missing from that of the other Imps. Your fellow circus-goers are uniformly boorish and boring. One or two situations, as well as the logical illogic needed to escape from them, smack of Infocom’s later social satire Bureaucracy, to which O’Neill (amongst many others) would make contributions.

>enter short line

You are now standing at the tail end of the short line.

>z

Time passes...

The face of the man ahead of you lights up as he spots something. "Hey, guys! It's ME, Jerry," he yells to a sizable group nearby, and they approach.

>z

Time passes...

"Haven't seen you turkeys in years. Howda hell are you guys?" They all reintroduce themselves. "Hey -- you clowns thirsty? Get in here, I'll buy y'all beer."

"You sure it's not a problem?" asks the catcher.

"Heck no, just scoot in right here."

With both your resolve and your heaving bosom firm against the crush of interlopers, you are nevertheless forced to backpedal.

>z

Time passes...

Jerry continues backslapping the second baseman.

>z

Time passes...

Jerry continues jiving with the center fielder.

>exit long line

You hear an inner voice whisper, "Do I really want to forfeit my position in the long line?" To which you answer:

>yes

You nonchalantly walk away from the long line.

>enter long line

A lot of other people must not have had the same idea as you, as they virtually hemorrhage over to the short line. Steaming to the front of the line, you get a two-dollar-and-25-cent frozen banana pushed at you and are whisked to the side before you can even count your change.

Ballyhoo was Infocom’s fourth game to be given the “Mystery” genre label. As such, it’s also an earnest attempt to solve a real or perceived problem that had long frustrated players of those previous three mysteries. The first of them, Deadline, had exploded the possibilities for adventure games by simulating a dynamic story with independent actors rather than just setting the player loose in a static world full of puzzles to solve; The Witness and Suspect had then continued along the same course. Instead of exploring a geographical space, the player’s primary task became to explore a story space, to learn how this dynamic system worked and to manipulate it to her own ends by judicious, precisely timed interference. While a huge advance that brought a new dimension to the adventure game, this seemingly much more story-oriented approach also remained paradoxically problematic to fully reconcile to the view of Infocom’s games as interactive fiction, as, as their box copy would have it, stories you “woke up inside” and proceeded to experience like the protagonist of a novel. The experience of playing one of these early mysteries was more like that of an editor, or a film director making an adaptation of the novel. You had to take the stories apart piece by piece through probing and experimentation, then put everything back together in a way that would guide the protagonist, from whom you stood at a decided remove, to the optimal ending. That process might offer pleasures all its own, but it kept the player firmly in the realm of puzzle-solver rather than fiction-enjoyer — or, if you like, guiding the fiction became the overarching puzzle. Even Infocom’s most unabashed attempt to create a “literary” work to date, Steve Meretzky’s A Mind Forever Voyaging, became abruptly, jarringly gamelike again when you got to the final section, where you had to head off a sequence of events that would otherwise be the end of you. In a film or novel based on A Mind Forever Voyaging, this sequence would just chance to play out in just the right way to let Perry Simm escape by the skin of his teeth and save the world in the process. In the game, however, the player was forced to figure out what dramatically satisfying narrative the author wanted to convey, then manipulate events to bring it to fruition, a very artificial process all the way around. Yet the alternative of a static environment given motion only when the player deigned to push on something was even farther from the idea of “interactive fiction” as a layperson might take that phrase. What to do?

Infocom’s answer, to which they first fully committed in Ballyhoo, was to flip the process on its head: to make the story respond to the player rather than always asking the player to respond to the story. Put another way, here the story chases the player rather than the player chasing the story. (Feel free to insert your “in Soviet Russia…” jokes here.) Ballyhoo is another dynamic mystery with its own collection of dramatic beats to work through. Now, though, the story moves forward only when and as the player’s actions make it most dramatically satisfying to do so, rather than ticking along according to its own remorseless timetable. So, for example, Comrade Thumb will struggle to get a drink of water from the public water fountain at the beginning of the game for hundreds of turns if necessary, until the player helps him by giving him a boost. He’ll then toddle off to another location to wait for the player to enter. When and only when she does, he’ll carry off his next dramatic beat. Later, a certain bumbling detective will wander onto the midway and pass out dead drunk just when the needs of the plot, as advanced by the player thus far, demand that he do so. Sometimes these developments are driven directly by the player, but at other times they happen only in the name of dramatic efficiency, of story logic. Rather than asking the player to construct a story from a bunch of component parts, now the author deconstructs the story she wants the player to experience, then figures out how to put it back together on the fly in a satisfying way in response to the player’s own actions — but without always making the fact that the story is responding to the player rather than unspooling on its own clear to the player. Ideally, this should let the player just enjoy the unfolding narrative from her perspective inside the story, which will always just happen to play out in suitably dramatic fashion, full of the close calls and crazy coincidences that are such part and parcel of story logic. Virtually unremarked at the time, this formal shift would eventually go on to become simply the way that adventure games were done, to the extent that the old Deadline approach stands out as a strange, cruel anomaly when it crops up on rare occasions on the modern landscape.

Depending on how you see these things, you might view this new approach as a major advance or as a disappointment, even as a capitulation of sorts. Early adventure writers, including those at Infocom, were very invested in the idea of their games as simulations of believable (if simplified) worlds. See, for instance, the article which Dave Lebling published in Byte in December of 1980, which, years before Infocom would dub their games “interactive fiction,” repeatedly refers to Zork and the other games like it that Infocom hopes to make as “computerized fantasy simulations.” Or see the flyer found in Zork I itself, which refers to that game as “a self-contained and self-maintaining universe.” To tinker with such a universe, to introduce a hand of God manipulating the levers in the name of drama and affect, felt and still feels wrong to some people. Most, however, have come to accept that pure, uncompromising simulation does not generally lead to a satisfying adventure game. Adventure games may be better viewed as storytelling and puzzle-solving engines — the relative emphasis placed on the former and the latter varying from work to work — wherein simulation elements are useful as long as they add verisimilitude and possibility without adding boredom and frustration, and stop being useful just as soon as the latter qualities begin to outweigh the former.

Which is not to say that this new approach of the story chasing the player is a magic bullet. Virtually everyone who’s played adventure games since Ballyhoo is familiar with the dilemma of a story engine that’s become stuck in place, of going over and over a game’s world looking for that one trigger you missed that will satisfy the game that all is in proper dramatic order and the next act can commence. My own heavily plotted adventure game is certainly not immune to this syndrome, which at its extreme can feel every bit as artificial and mimesis-destroying, and almost as frustrating, as needing to replay a game over and over with knowledge from past lives. Like so much else in life and game design, this sort of reactive storytelling is an imperfect solution, whose biggest virtue is that most people prefer its brand of occasional frustration to others.

And now we’ve come to the point in this article where I need to tell you why, despite pioneering such a major philosophical shift and despite a wonderful setting brought to life by some fine writing, Ballyhoo does indeed deserve its spot amongst the lower tier of Infocom games. The game has some deep-rooted problems that spoil much of what’s so good about it.

The most fundamental issue, one which badly damages Ballyhoo as both a coherent piece of fiction and a playable game, is that of motivation — or rather lack thereof. When the game begins you’re just another vaguely dissatisfied customer exiting the big top along with the rest of the maddening crowd. Getting the plot proper rolling by learning about the mystery itself — proprietor Munrab’s young daughter Chelsea has been kidnapped, possibly by one of his own discontented performers — requires you to sneak into a storage tent for no reason whatsoever. You then eavesdrop on a fortuitous conversation which occurs, thanks to Ballyhoo‘s new dramatic engine, just at the right moment. And so you decide that you are better equipped to solve the case than the uninterested and besotted detective Munrab has hired. But really, what kind of creepy busybody goes to the circus and then starts crawling around in the dark through forbidden areas just for kicks? Ballyhoo makes only the most minimal of attempts to explain such behavior in its opening passage: “The circus is a reminder of your own secret irrational desire to steal the spotlight, to defy death, and to bask in the thunder of applause.” That’s one of the most interesting and potential-fraught passages in the game, but Ballyhoo unfortunately makes no more real effort to explore this psychological theme, leaving the protagonist otherwise a largely blank slate. Especially given that the mystery at the heart of the game is quite low-stakes — the kidnapping is so clearly amateurish that Chelsea is hardly likely to suffer any real harm, while other dastardly revelations like the presence of an underground poker game aren’t exactly Godfather material — you’re left wondering why you’re here at all, why you’re sticking your nose into all this business that has nothing to do with you. In short, why do you care about any of this? Don’t you have anything better to be doing?

A similar aimlessness afflicts the puzzle structure. Ballyhoo never does muster that satisfying feeling of really building toward the solution of its central mystery. Instead, it just offers a bunch of situations that are clearly puzzles to be solved, but never gives you a clue why you should be solving them. For instance, you come upon a couple of lions in a locked cage which otherwise contains nothing other than a lion stand used in the lion trainer’s act. You soon find a key to the cage and a bullwhip. You have no use for the lion stand right now, nor for the lions themselves, nor for their cage. There’s obviously a puzzle to be solved here, but why? Well, if you do so and figure out how to deal with the lions, you’ll discover an important clue under the lion stand. But, with no possible way to know it was there, why on earth would any person risk her neck to enter a lion cage for no reason whatsoever? (Presumably the same kind that would creep into a circus’s supply tent…) Elsewhere you come upon an elephant in a tent. Later you have the opportunity to collect a mouse. You can probably imagine what you need to do, but, again, why? Why are you terrorizing this poor animal in its tiny, empty tent? More specifically, how could you anticipate that the elephant will bolt away in the perfect direction to knock down a certain section of fence? This George Mallory approach to design is everywhere in Ballyhoo. While “because it’s there” has been used plenty of times in justifying adventure-game puzzles both before and after Ballyhoo, Infocom by this time was usually much, much better at embedding puzzles within their games’ fictions.

With such an opaque puzzle structure, Ballyhoo becomes a very tough nut to crack; it’s never clear what problems you should be working on at any given time, nor how solving any given puzzle is likely to help you with the rest. It all just feels… random. And many of the individual solutions are really, really obscure, occasionally with a “read Jeff O’Neill’s mind” quality that pushes them past the boundary of fairness. Making things still more difficult are occasional struggles with the parser of the sort we’re just not used to seeing from Infocom by this stage: you can MOVE that moose head on the wall, but don’t try to TURN it. There’s also at least one significant bug that forced me to restore on my recent playthrough (the turnstile inexplicably stopped recognizing my ticket) and a few scattered typos. Again, these sorts of minor fit-and-finish problems are hardly surprising in general, but are surprising to find in an Infocom game of this vintage.

Assuming we give some of Hitchhiker’s dodgier elements a pass in the name of letting Douglas Adams be Douglas Adams, we have to go all the way back to those early days of Zork and Deadline to find an Infocom game with as many basic problems as this one. Ballyhoo isn’t, mind you, a complete reversion to the bad old days of 1982. Even leaving aside its bold new approach to plotting, much in Ballyhoo shows a very progressive sensibility. On at least one occasion when you’re on the verge of locking yourself out of victory, the game steers you to safety, saying that “the image of a burning bridge suddenly pops into your mind.” Yet on others it seems to positively delight in screwing you over. My theory, which is only that, is that Ballyhoo was adversely affected by the chaos inside Infocom as it neared release, that it didn’t get the full benefit of a usually exhaustive testing regime that normally rooted out not only bugs and implementation problems but also exactly the sorts of design issues that I’ve just pointed out. Thankfully, Ballyhoo would prove to be an anomaly; the games that succeeded it would once again evince the level of polish we’ve come to expect. Given that Ballyhoo was also the product of a first-time author, its failings are perhaps the result of a perfect storm of inexperience combined with distraction.

Ballyhoo was not, as you’ve probably guessed, a big seller, failing to break 30,000 copies in lifetime sales. It’s a paradoxical little game that I kind of love on one level but can’t really recommend on another. Certainly there’s much about it to which I really respond. Whether because I’m a melancholy soul at heart or because I just like to play at being one from time to time, I’m a sucker for its sort of ramshackle splendid decay. I’m such a sucker for it, in fact, that I dearly want Ballyhoo to be better than it is, to actually be the sad and beautiful work of interactive fiction that I sense it wants to be. I’ve occasionally overpraised it in the past for just that reason. But we also have to consider how well Ballyhoo works as an adventure game, and in that sense it’s a fairly broken creation. I won’t suggest that you tax yourself too much trying to actually solve it by yourself, but it’s well worth a bit of wandering around just to soak up its delicious melancholy.

Brian Bagnall

December 22, 2014 at 2:53 pm

Thank you for clearly explaining the massive innovation O’Neill brought to the genre. He really hit on something there. I had a similar experience of being initially attracted to the mood of the game but ultimately wandering around a bit before losing interest.

Oh to be granted a full interview with him! If he has a change of heart it would likely make a good article on its own.

Jason Scott

December 22, 2014 at 4:58 pm

When interviewing the implementors, many of them were sad to have fallen out of touch with Jeff. It is been a while, but I definitely remember him more than once being referred to as The Lost Imp.

More importantly, though, I just want to stress that not everyone I interviewed had positive memories of their time there. One of the requests by Mike Berlyn was that I not portray him as having admired or respected the company management, and for the time, he considered rescinding agreement to appear in the final documentary. Like everyone else, I gave them a chance to see the film or at least their portrayal in the film before release so they could sign off, and he was happy with how it came out.

(Mike is fighting a cancer battle right now, much love to Mike.)

Jimmy Maher

December 22, 2014 at 5:45 pm

I’m very sorry to hear of Mike’s illness. I and (I’m sure) everyone who reads this blog wish him all the best.

Steve Meretzky was in contact with Jeff to at least the extent that he had a current email to pass along to me, albeit with the warning that “his memories of Infocom are not happy ones.” Jeff was kind enough to reply, and even to consider an interview, but ultimately decided against it, which is of course his right. But if you’re reading, Jeff, you’re obviously missed by some old friends!

Lisa H.

December 22, 2014 at 9:28 pm

Incredible as this may sound to those of us today who persist in viewing the company’s brief life as a sort of Camelot

I know what you meant, but my first thought was “You mean, it was a silly place?”

that time in his own life is one that O’Neill would rather forgot

Forget.

he become one of Infocom’s in-house testers.

Became. (having some tense problems here?)

Ballyhoo‘s own collection of freaks are less extreme

You’ve got an odd apostrophe there (an “ayn”, is it?). Also, I think you want “is”, to agree in number with “collection”.

Jimmy Maher

December 23, 2014 at 6:51 am

Thanks! Fixed except for the Camelot thing, which I submit is your personal problem. ;)

Lisa H.

December 24, 2014 at 1:45 am

Yeah, that was just tongue in cheek on my part. :)

ZUrlocker

December 23, 2014 at 2:21 am

Great post. I always enjoy getting a broader understanding of how Interactive Fiction has evolved. It seems Ballyhoo had more to it than I had thought.

Would be great to hear from all the Infocom authors, whether they were enamored with the company or not. Or maybe especially if not. There’s an insider perspective that is invaluable to understanding the history and evolution.

As a minor point, I found the last sentence of the first paragraph (“In fact… of the 1980s.”) to be almost impossible to parse. Grammatically it may be correct, but I would definitely consider breaking it up and simplifying.

Jimmy Maher

December 23, 2014 at 7:29 am

I think there’s a pretty good consensus already on the subject from just about everyone Jason interviewed: loved their colleagues; loved the wing of management represented by Joel Berez; hated the wings of management represented by Al Vezza and later by Bruce Davis of Activision, which unfortunately generally had a lot more say in the really big decisions than did Berez. The main variation is how *personally* they take Infocom’s management’s failings. This ranges from a shrug and a “well, everybody just did the best they could and we should all just leave the past in the past” to active, continuing anger and bitterness. In the case of those inclined more toward the latter, well, I’m obviously fairly obsessive about Infocom, but I don’t see a need to air dirty laundry just for the sake of it (not that I mean to imply that that was necessarily what you were suggesting).

And maybe it comes from having read too much Dickens, but I kind of like to use long sentence like that one from time to time. It’s one of the things that sets my writing apart — in a good way I’d like to think, but, as your reaction shows, mileages may definitely vary. ;)

Rob

December 23, 2014 at 4:31 am

Joseph Merrick (not John), and George Mallory (not Hillary).

Jimmy Maher

December 23, 2014 at 6:52 am

I was having some serious name problems, wasn’t I? Fixed, and thanks!

Hresna

January 11, 2025 at 12:44 pm

I also only knew him as John Merrick before reading this Article.

I’m going to blame the BNL.

Healy

December 23, 2014 at 7:04 am

“I’m such a sucker for it, in fact, that I dearly want Ballyhoo to be better than it is, to actually be the sad and beautiful work of interactive fiction that I sense it wants to be. I’ve occasionally overpraised it in the past for just that reason.”

So, you say you have a tendency to ballyhoo Ballyhoo?

(I’m so sorry.)

Jimmy Maher

December 23, 2014 at 7:30 am

:)

Dehumanizer

December 23, 2014 at 12:04 pm

Insert obligatory “great post, etc.” :)

Minor typo: “Perry Sim” should be “Perry Simm”.

Jimmy Maher

December 23, 2014 at 12:17 pm

Thanks!

Brian Moriarty

December 23, 2014 at 3:25 pm

Thanks for giving Ballyhoo the thoughtful look it deserves.

Jeff and I lived with a handful of other guys in a Concord farmhouse during the Infocom years. An enigmatic personality, private and intense, proud, hard-working, passionate, with the smoldering edge of a black Irishman. Irresistible to those who dared approach.

He was our Kerouac, Brando, Jones Very.

His two games are among the most interesting in the canon. Pity he abandoned the form and fell silent.

Happily, Jeff agreed to a substantial video interview for an upcoming Infocom multimedia project, taking his place in the history of that remarkable company.

Jimmy Maher

December 23, 2014 at 8:58 pm

Really glad to hear that Jeff will be giving his perspective at last. And very interested to see this project you mention…

Jason Scott

December 26, 2014 at 5:22 pm

Oh, great to hear! I’m assuming this is the project that was started along GET LAMP. If so, that thing is going to make GET LAMP’s take on Infocom look like a People magazine article, which is fantastic.

Victor

March 29, 2019 at 8:11 pm

Did this project get completed? (He asks 5 years late)

Mike

April 8, 2023 at 4:29 pm

Asking four years after that! Shame that it seems to have fallen through.

Sniffnoy

December 23, 2014 at 6:36 pm

“Story responding to player” can get very annoying sometimes when the story responds in an arbitrary way (you found the princess, so they’ve finished building that bridge!) but as long as there’s at least some predictability or connection (maybe if I get the guy what he wants, he’ll go somewhere else, and maybe that will be where I need him to be) it’s not so bad…

Also, one writing nitpick: I think the phrase “disinterested and besotted detective” would be clearer if you replaced “disinterested” with “uninterested”; the other meaning of “disinterested” kind of competes here.

Jimmy Maher

December 23, 2014 at 8:57 pm

Fair enough. Thanks!

Duncan Stevens

December 23, 2014 at 10:57 pm

Another parser problem (spoiler):

One of the required commands in the lion cage is WHIP LION, by which the game means that you crack the whip. HIT THE LION WITH THE WHIP elicits an entirely different response.

Mark Ricard

April 8, 2015 at 5:35 pm

Very informative review. I read a interview where you praised this game and to honest was a bit disappointed by it because some of the puzzles were really obscure. Reading this makes your views more understandable. The mood of the story just seemed cliched to me and it seems that is what you responded to the most about the game. Perhaps that predicates ones enjoyment of Ballyhoo.

Nord and Bert was both a more interesting and original game. Have you written about it yet?

Jonathan Blask

August 2, 2015 at 5:37 pm

Can’t believe I missed this one. I covered “Ballyhoo” on my Old-School Transcripts site. For the most part, I think I uncovered most of its gems (although it has been brought to my attention that I missed the response to >TAKE SAWDUST ):

http://oldschooltranscripts.blogspot.com/2013/04/ballyhoo-oneill-infocom.html

Adele

January 25, 2016 at 1:16 am

I am a long-time reader, and I always find your asides and details interesting and worthy of further research (note: I am a librarian, and read your blog during the long hours at the reference desk.)

I tried to read more about Jeff O’Neill, and I found it interesting that there isn’t even a Wikipedia snippet on him. Instead, there are many features on a professional hockey player who shares the same name with the same exact spelling. It’s interesting to me that this man with such an important role in the history of modern computing successfully remains anonymous; aside from his own wishes, it seems like armchair historians and fans would have put more information out there. Thanks for the interesting little breadcrumbs that always make me delve deeper into the history.

And I suppose it goes without saying that the full article is great, outside of the little details that I like to dig up. Thank you for enlightening my reference shifts!

Jason Kankiewicz

September 23, 2017 at 3:28 am

“

in teary silence.” -> “in teary silence.“?“on at at any” -> “on at any”?

Jimmy Maher

September 23, 2017 at 9:13 am

Thanks!

Chris Lang

June 6, 2019 at 11:45 pm

The structure of ‘events being triggered after player does enough things’ certainly lives on post-Infocom in many of the later interactive fiction works such as Christminster up to the popular Ace Attorney series during their ‘investigation’ segments. (There’s a lot of just wandering around, doing stuff and then going back to the detention center to see if your client is available for questioning, or going somewhere else to see if anything’s different – if nothing’s changed, then you haven’t found all the items and exhausted all the most important conversation possibilities yet). And I have to agree that they can be just as dangerous to immersion as the Deadline time structure that requires you to learn by previous sessions.

As much as I liked the game and its setting, the elephant puzzle is one thing that always bothered me. It’s completely unmotivated. There’s no real reason to believe there’s anything in the elephant tent aside from what you expect to find there (and indeed, there isn’t). And indeed, how can we anticipate that our actions here cause the elephant to smash a fence and open up a new location for us to visit?

And furthermore, there doesn’t seem to be any way to ‘fix’ this to make it work.

At least with the lions’ cage, one can imagine Harry (the blind doorkeeper who’s more willing to talk about everything than most of the characters) telling us he heard something got dropped in the cage, or maybe overhearing a conversation in the gambling den along these lines. Something like….

Voices drift over from the poker game. You hear bits and pieces of a conversation. “… heard he dropped it in the lion’s den.” “Probably still there. Roustabout gets lazy, sweeps stuff under rug…” The voices quiet and you can hear no more.

As it is in the game, however, no such hint exists that there’s anything worth disturbing the lions for. The above is me just thinking of a possible ‘fix’ for it on the spot some three decades after the fact.

Sadly, had I been a playtester back then, I don’t know what I would have suggested to fix the elephant problem. I don’t know what could be done to suggest to the player that messing with the elephant could in any way be a good idea.

Joe

November 17, 2022 at 4:52 pm

There could have been one more clue in the elephant tent that was foreshadowed to the player in some way and then just had the elephant knocking a hole in the fence be a side effect.

Torbjörn Andersson

June 14, 2020 at 9:18 am

“So, for example, Comrade Thumb will struggle to get a drink of water from the public water fountain at the beginning of the game for hundreds of turns if necessary, until the player helps him by giving him a boost.”

Well, once you’ve seen him he’ll stay around for a couple of moves before giving up. Then he’ll leave, whether or not you are there to see it. But it’s true that you can’t miss the event because he’ll always be there the first time you enter that room.

“There’s also at least one significant bug that forced me to restore on my recent playthrough (the turnstile inexplicably stopped recognizing my ticket)”

I’m guessing you were bit by this bug: https://github.com/the-infocom-files/ballyhoo/issues/11

If I understand it correctly, the parser will scan ahead to see if you’re using the words like “head” or “front” in particular ways, and set a flag if you do. This was apparently inherited and extended from how The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy dealt with “put X in front of Y” or “lie down in front of X”. Here it’s probably for things like “go to front of line” etc.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t check if it’s going outside of what was written to the buffer by the current command, so if there’s left-overs there from a previous command it may still interpret “put ticket in slot” as “put ticket in front of slot”.

I still don’t know exactly what kind of commands will trigger the bug, or how long it will persist. The most likely thing I’ve come across so far (which I stumbled over many years ago) is “rimshaw, feel my head”, and that’s close enough to the turnstile for me to be able to reproduce it.

Lisa H.

June 14, 2020 at 4:53 pm

Interesting stuff!

Aaron

June 14, 2025 at 5:39 pm

“the view of Infocom’s games as interactive fiction, as, as their box copy would have it”

I think that middle “as” is unneeded.

Jimmy Maher

June 16, 2025 at 7:33 am

Thanks, but as intended. ;)

Adam Huemer

June 21, 2025 at 10:14 am

Oh, nice. I totally forgot this neat little game. Glad you didn’t.