I touched on the history of Brian Fargo and his company Interplay some time ago, when I looked at the impact of The Bard’s Tale, their breakout CRPG hit that briefly replaced the Wizardry series as the go-to yin to Ultima‘s yang and in the process transformed Interplay almost overnight from a minor developer to one of the leading lights of the industry. They deserve more than such cursory treatment, however, for The Bard’s Tale would prove to be only the beginning of Interplay’s legacy. Let’s lay the groundwork for that future today by looking at how it all got started.

Born into suburban comfort in Orange County, California, in 1962, Brian Fargo manifested from an early age a peculiar genius for crossing boundaries that has served him well throughout his life. In high school he devoured fantasy and science-fiction novels and comics, spent endless hours locked in his room hacking on his Apple II, and played Dungeons and Dragons religiously in cellars and school cafeterias. At the same time, though, he was also a standout athlete at his school, a star of the football team and so good a sprinter that he and his coaches harbored ambitions for a while of making the United States Olympic Team. The Berlin Wall that divides the jocks from the nerds in high school crumbled before Fargo. So it would be throughout his life. In years to come he would be able to spend a day at the office discussing the mechanics of Dungeons and Dragons, then head out for an A-list cocktail party amongst the Hollywood jet set with his good friend Timothy Leary. By the time Interplay peaked in the late 1990s, he would be a noted desirable bachelor amongst the Orange County upper crust (“When he’s not at a terminal he can usually be found rowing, surfing, or fishing”), making the society pages for opening a luxury shoe and accessory boutique, for hosting lavish parties, for planning his wedding at the Ritz-Carlton. All whilst continuing to make and — perhaps more importantly — continuing to openly love nerdy games about killing fantasy monsters. Somehow Brian Fargo made it all look so easy.

But before all that he was just a suburban kid who loved games, whether played on the tabletop, in the arcade, on the Atari VCS, or on his beloved Apple II. Softline magazine, the game-centric spinoff of the voice-of-the-Apple-II-community Softalk, gives us a glimpse of young Fargo the rabid gamer. He’s a regular fixture of the high-score tables the magazine published, excelling at California Pacific’s Apple II knock-off of the arcade game Head-On as well as the swordfighting game Swashbuckler. Already a smooth diplomat, he steps in to soothe a budding controversy when someone claims to have run up a score in Swashbuckler of 1501, a feat that others claim is impossible because the score rolls over to 0 after 255. It seems, Fargo patiently explains, that there are two versions of the game, one of which rolls over and one of which doesn’t, so everyone is right. But the most tangible clue to his future is provided by the question he managed to get published in the January 1982 issue: “How does one get so many pictures onto one disk, such as in The Wizard and the Princess, where On-Line has more than 200 pictures, with a program for the adventure on top of that?” Yes, Brian Fargo the track star had decided to give up his Olympic dream and become a game developer.

By that time Fargo was 19, and a somewhat reluctant student at the University of California, Irvine as well as a repair technician at ComputerLand. No more than an adequate BASIC programmer — he would allow even that ability to atrophy as soon as he could find a way to get someone else to do his coding for him — Fargo knew that he hadn’t a prayer of creating one of the action games that littered Softline‘s high-score rankings, nor anything as complex as Ultima or Wizardry, the two CRPGs currently taking the Apple II world by storm. He did, however, think he might just be up to doing an illustrated adventure game in the style of The Wizard and the Princess. He recruited one Michael Cranford, a Dungeons and Dragons buddy and fellow hacker from high school, to draw the pictures he’d need on paper; he then traced them and colored them on his Apple II. He convinced another friend to write him a few machine-language routines for displaying the graphics. And to make use of it all he wrote a simple BASIC adventure game: you must escape the Demon’s Forge, “an ancient test of wisdom and battle skill.” Desperate for some snazzy cover art, he licensed a cheesecake fantasy print in the style of Boris Vallejo, featuring a shapely woman tied to a pole being menaced by two knights mounted on some sort of flying snakes — this despite a notable lack of snakes (flying or otherwise), scantily-clad females, or for that matter poles in the game proper. (The full Freudian implications of this box art, not to mention the sentence I’ve just written about it, would doubtless take a lifetime of psychotherapy to unravel.)

The Demon’s Forge box art, which won Softline magazine’s sarcastic Relevance in Packaging Award, with Flying-Snakes-and-Ladies-in-Bondage clusters.

Fargo employed a guerrilla-marketing technique that would have made Wild Bill Stealey proud to sell The Demon’s Forge under his new imprint of Saber Software. He took out a single advertisement in Softalk for $2500. Then he started calling stores around the country to ask about his game, claiming to be a potential customer who had seen the advertisement: “A few minutes later my other line would ring and the retailer would place an order.” It didn’t make him big money, but he made a little. Then along came Michael Boone.

Boone was another old high-school friend, a scion of petroleum wealth who had dutifully gone off to Stanford to study petroleum engineering, only to be distracted by the lure of entrepreneurship. For some time he vacillated between starting a software company and an ice-cream chain, deciding on the former when his family’s connections came through with an injection of venture capital. His long-term plan was to make a golf simulation for the new IBM PC: “IBM seemed like the computer that business people and the affluent were buying. So, I should write a golf game for the IBM computer.” Knowing little about programming and needing some product to get him started, he offered to buy out Fargo’s The Demon’s Forge and his Saber Software for a modest $5000, and have Fargo come work for him. Fargo dropped out of university to do so in late 1982. He assembled a talented little development team consisting of programmers “Burger” Bill Heineman and Troy Worrell along with himself, right there in his and Boone’s hometown of Newport Beach. [1]Bill Heineman now lives as Rebecca Heineman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times.

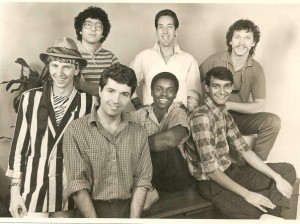

Boone Corporation, 1983. Michael Boone is first from left, Bill Heineman second, Troy Worrell fourth, Brian Fargo fifth. They’re toasting with Hires Root Beer. “Hires Root Beer,” “Hi-Res graphics.” Get it?

After porting The Demon’s Forge to the IBM PC, Fargo’s little team occupied themselves writing quick-and-dirty cartridge games like Chuck Norris Superkicks and Robin Hood for the Atari VCS, ColecoVision, and the Commodore VIC-20 and 64. These were published without attribution by Xonox, a spinoff of K-tel Records, one of many dodgy players flooding the market with substandard product during the lead-up to the Great Videogame Crash. Michael Boone agreed to publish under his own imprint a couple of VIC-20 action games — Crater Raider and Cyclon — written by a talented programmer named Alan Pavlish whom Fargo knew well. Meanwhile work proceeded slowly on Boone’s golf simulation for the rich, which was now to be a “tree-for-tree, inch-for-inch recreation of the course at Pebble Beach.” When some Demon’s Forge players called to ask for a hint, Fargo learned that they were part of a company trying to get traction for the Moodies, a bunch of pixieish would-be cartoon characters derivative of the Smurfs; soon they came in to sign a contract for a game to be called Moodies in Iceland.

But then came the Crash. One day shortly thereafter Boone walked into the office and announced that he was taking the company in another direction: to make dry-erase boards instead of computer games. Since Fargo and his team had no particular competency in that field, they were all out of a job. Boone’s new venture would prove to be hugely successful, giving us the whiteboards now ubiquitous to seemingly every office or cubicle in the world and making Boone himself very, very rich. But even had they been able to predict his future that wouldn’t have been much consolation for Fargo and his suddenly forlorn little pair of programmers.

Fargo decided that it really shouldn’t be that hard for him to do what Michael Boone had been doing in addition to managing the development team. In fact, he had already been working on a side venture, a potential $60,000 contract with World Book Encyclopedia to make some rote educational titles of the drill-and-practice stripe. After signing that contract, he founded Interplay Productions to see it through. It wasn’t a glamorous beginning, but it represented programs that could be knocked out quickly to start bringing in money. Heineman and Worrell agreed to stay with Fargo and try to make it work. Fargo added another programmer named Jay Patel to complete this initial incarnation of Interplay. The next six to nine months consisted of Fargo hustling up whatever work he could find, game or non-game, and his team hammering it out: “We did work for the military, stuff for McGraw Hill — we did anything we could do. We didn’t have the luxury of creating our own software. We had to do other people’s work and just kept our ideas in the back of our minds.”

The big break they’d been hoping for came midway through 1984. Interplay “hit Activision’s radar,” and Activision decided to let Fargo and company make some adventure games for them. Activision at the time was reeling from the Great Videogame Crash, which had destroyed their immensely profitable cartridge business almost overnight. CEO Jim Levy had decided that the future of the company, if it was to have one, must lie with software for home computers. With little expertise in this area, he was happy to sign up even an unproven outside developer like the nascent Interplay. Mindshadow and The Tracer Sanction, the first two games Interplay was actually willing to put their name on, were the results.

Fargo’s team had found time to dissect Infocom games and tinker with parsers and adventure-game engines even back during their days as Boone Corporation. Mindshadow and Tracer Sanction were logical extensions of that experimentation and, going back even further, of Fargo’s first game The Demon’s Forge. Fargo found a young artist named Dave Lowery, who would go on to quite an impressive career in film, to draw the pictures for Mindshadow; they came out looking a cut above most of the competition in the crowded field of illustrated adventure games. Mindshadow‘s Bourne Identity-inspired plot has you waking up with amnesia on a deserted island. Once you escape the island, you embark on a globe-trotting quest to recover your memories. There’s an interesting metaphysical angle to a game that’s otherwise fairly typical of its period and genre. As you encounter new people, places, and things that you should know from your earlier life, you can use the verb “remember” to fit them into place and slowly rebuild your shattered identity.

Mindshadow did relatively well for Interplay and Activision, not a blockbuster but a solid seller that seemed to bode well for future collaborations. Less successful both aesthetically and commercially was Tracer Sanction, a science-fiction adventure that isn’t quite sure whether it wants to be serious or humorous and lacks a conceptual hook like Mindshadow‘s “remember” gimmick. But by the time it appeared Fargo had already shifted much of his team’s energy away from adventure games and into the CRPG project that would become The Bard’s Tale.

Fargo and his old high-school buddy Michael Cranford had been dreaming of doing a CRPG since about five minutes after they had first seen Wizardry back in 1981. Cranford had even made a stripped-down CRPG on his own, published on a Commodore 64 cartridge by Human Engineered Software under the title Maze Master in 1983 to paltry sales. Now Fargo convinced him to help his little team at Interplay create a Wizardry killer. It seemed high time for such an undertaking, what with the Wizardry series still using ugly monochrome wire frames to depict its dungeons and monsters and available only on the Apple II, Macintosh, and IBM PC — a list which notably didn’t include the biggest platform in the industry, the Commodore 64. Indeed, CRPGs of any sort were quite thin on the ground for the Commodore 64, decent ones even more so. Fargo:

At the time, the gold standard was Wizardry for that type of game. There was Ultima, but that was a different experience, a top-down view, and not really as party-based. Sir-Tech was kind of saying, “Who needs color? Who needs music? Who needs sound effects?” But my attitude was, “We want to find a way to use all those things. What better than to have a main character who uses music as part of who he is?”

Soon the game was far enough along for Fargo to start shopping it to publishers. His first stop was naturally Activision. One of Jim Levy’s major blind spots, however, was the whole CRPG genre. He simply couldn’t understand the appeal of killing monsters, mapping dungeons, and building characters, reportedly pronouncing Interplay’s project “nicheware for nerds.” And so Fargo ended up across town at Electronic Arts, who, recognizing that Trip Hawkins’s original conception of “simple, hot, and deep” wasn’t quite the be-all end-all in a world where all entertainment software was effectively “nicheware for nerds,” were eager to diversify into more hardcore genres like the CRPG. EA’s marketing director Bing Gordon zeroed in on the appeal of one of Cranford’s relatively few expansions on Wizardry, the character of the bard. He went so far as to change the game’s name from Shadow Snare to The Bard’s Tale to highlight him, creating a lovable rogue to serve as the star of advertisements and box copy who barely exists in the game proper: “When the going gets tough, the bard goes drinking.” Beyond that, promoting The Bard’s Tale was just a matter of trumpeting the game’s audiovisual appeal in contrast to the likes of Wizardry. Released in plenty of time for Christmas 1985, with all of EA’s considerable promotional savvy and financial muscle behind it, The Bard’s Tale shocked even its creators and its publisher by outselling the long-awaited Ultima IV that appeared just a few weeks later. Interplay had come into the big time; Fargo’s days of scrabbling after any work he could find looked to be over for a long, long time to come. In the end, The Bard’s Tale would sell more than 400,000 copies, becoming the best-selling single CRPG of the 1980s.

The inevitable Bard’s Tale sequel was completed and shipped barely a year later. Another solid hit at the time on the strength of its burgeoning franchise’s name, it’s generally less fondly remembered today by fans. It seems that Michael Cranford and Fargo had had a last-minute falling-out over royalties just as the first Bard’s Tale was being completed, which led to Cranford literally holding the final version of the game for ransom until a new agreement was reached. A new deal was brokered in the nick of time, but the relationship between Cranford and Interplay was irretrievably soured. Cranford was allowed to make The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight, but he did so almost entirely on his own, using much of the tools and code he and Interplay’s core team had developed together for the first game. The lack of oversight and testing led to a game that was insanely punishing even by the standards of the era, one that often felt sadistic just for the sake of it. Afterward Cranford parted company with Interplay forever to study theology and philosophy at university.

Despite having rejected The Bard’s Tale themselves, Activision was less than thrilled with Interplay’s decision to publish the games through EA, especially after they turned into exactly the sorts of raging hits that they desperately needed for themselves. Fargo notes that Activision and EA “just hated each other,” far more so even than was the norm in an increasingly competitive industry. Perhaps they were just too much alike. Jim Levy and Trip Hawkins both liked to think of themselves as hip, with-it guys selling the future of art and entertainment to equally hip, with-it buyers. Both were fond of terms like “software artist,” and both drew much of their marketing and management approaches from the world of rock and roll. Little Interplay had a tough task tiptoeing between these two bellicose elephants. Fargo:

We were maybe the only developer doing work for both companies at the same time, and they just grilled me whenever they had the chance. Whenever there was any kind of leak, they’d say, “Did you say anything?” I was right in the middle there. I always made sure to keep my mouth shut about everything.

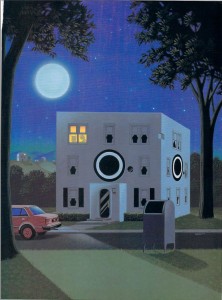

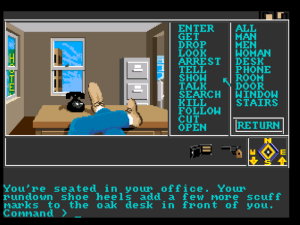

Still, Fargo managed for a while to continue doing adventure games for Activision alongside CRPGs for EA. Interplay’s Activision adventure for 1985, Borrowed Time, might just be their best. It was created at that interesting moment when developers were beginning to realize that traditional parser-based adventure games, even of the illustrated variety, might not cut it commercially much longer, but when they weren’t yet quite sure how to evolve the genre to make it more accessible and not seem like a hopeless anachronism on slick new machines like the Atari ST and Amiga. Borrowed Time is built on the same engine that had already powered Mindshadow and The Tracer Sanction, but it sports an attempt at providing an alternative to the keyboard via a list of verbs and nouns and a clickable graphic inventory. It’s all pretty half-baked, however, in that the list of nouns are suitable to the office where you start the game but bizarrely never change thereafter, while there are no hotspots on the pictures proper. Nor does the verb list contain all the verbs you actually need to finish the game. Thus even the most enthusiastic point-and-clicker can only expect to switch back and forth constantly between mouse or joystick and keyboard, a process that strikes me as much more annoying than just typing everything.

Thankfully, the game has been thought through more than its interface. Realizing that neither he nor anyone else amongst the standard Interplay crew were all that good at writing prose, Fargo contacted Bill Kunkel, otherwise known as “The Game Doctor,” who had made a name for himself as a sort of Hunter S. Thompson of videogame journalism via his column in Electronic Games magazine. Fargo’s pitch was simple: “Okay, you guys have a lot of opinions about games, how would you like to do one?” Kunkel, along with some old friends and colleagues named Arnie Katz and Joyce Worley, decided that they would like that very much, forming a little company called Subway Software to represent their partnership. Subway proceeded to write all of the text and do much of the design for Borrowed Time. Fargo gave them a “Script by” credit for their contributions, the first of many such design credits Subway would receive over the years to come (a list that includes Star Trek: First Contact for Simon & Schuster).

Like Déjà Vu, ICOM Simulations’s breakthrough point-and-click graphic adventure of the same year, Borrowed Time plays in the hard-boiled 1930s milieu of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. The tones and styles of the two games are very similar. Both love to make sardonic fun of the hapless, down-on-his-luck PI who serves as protagonist almost as much as they love to kill him, and both mix opportunities for free exploration with breakneck chases and other linear bits of derring-do in service of some unusually complicated plots. And I like both games on the whole, despite some unforgiving old-school design decisions. While necessarily minimalist given the limitations of Interplay’s engine, the text of Borrowed Time in particular is pretty good at evoking its era and genre inspirations.

Collaborations like the one that led to Borrowed Time highlight one of the most interesting aspects of Fargo’s approach to game development. In progress as well in many other companies by the mid-1980s, it represented a quiet revolution in the way games got made that was changing the industry.

With Interplay, I wanted to take [development] beyond one- or two-man teams. That sounds like an obvious idea now, but to hire an artist to do the art, a musician to do the music, a writer to do the writing, all opposed to just the one-man show doing everything, was novel. Even with Demon’s Forge, I had my buddy Michael do all the art, but I had to trace it all and put it in the computer, and that lost a certain something. And because I didn’t know a musician or a sound guy, it had no music or sound. I did the writing, but I don’t think that’s my strong point. So, really, [Interplay was] set up to say, “Let’s take a team approach and bring in specialists.”

One of the specialists Fargo brought in for Interplay’s fourth and final adventure game for Activision, 1986’s Tass Times in Tonetown, we already know very well.

After leaving Infocom in early 1985, just in time to avoid the chaos and pain brought on by Cornerstone’s failure, Mike Berlyn along with his wife Muffy had hung out their shingle as Brainwave Creations. The idea was to work as consultants, doing game design only rather than implementation — yet another sign of the rapidly encroaching era of the specialist. Brainwave entered talks with several companies, including Brøderbund, Origin, and even Infocom. However, with the industry in general and the adventure game in particular in a state of uncertain flux, it wasn’t until Interplay came calling that anything came to fruition. Brian Fargo gave Mike and Muffy carte blanche to do whatever they wanted, as long as it was an adventure game. What they came up with was a bizarre day-glo riff on New Wave music culture, with some of the looks and sensibilities of The Jetsons. The adjective “tass,” the game’s universal designation for anything cool, fun, good, or desirable, hails from the Latin “veritas” — truth. The Berlyns took to pronouncing it as “very tass,” and soon “tass” was born. In the extra-dimensional city of Tonetown guitar picks stand in for money, a talking dog is a star reporter, and a “combination of pig, raccoon, and crocodile” named Franklin Snarl is trying to buy up all of the land, build tract houses, and transform the place into a boring echo of Middle American suburbia. Oh, and he’s also kidnapped your dimension-hopping grandfather. That’s where you come in.

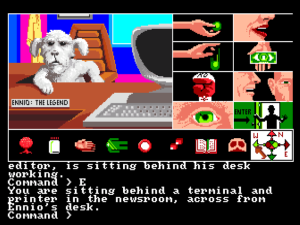

I’ve heard Tass Times in Tonetown described from time to time as a “cult classic,” and who am I to argue? It’s certainly appealing at first blush, when you peruse the charmingly cracked Tonetown Times newspaper included in its package. The newspaper gives ample space to Ennio, the aforementioned dog reporter who owes more than a little something to the similarly anthropomorphic and similarly cute dogs of Berlyn’s last game for Infocom, the computerized board game Fooblitzky. It seems old Ennio — whom Berlyn named after film composer Ennio Morricone of spaghetti western fame — has been investigating the mundane dimension from which you hail under deep cover as your gramps’s dog Spot. Interplay’s adventure engine, while still clearly derivative of the earlier games, has been vastly improved, with icons now taking the place of lists of words and the graphics themselves filled — finally — with clickable hotspots. The bright, cartoon-surrealistic graphics still look great today, particularly in the Amiga version.

Settle in to really, seriously play, though, and problems quickly start to surface. It’s hard to believe that this game was co-authored by someone who had matriculated for almost three years at Infocom because it’s absolutely riddled with exactly the sort of frustrations that Infocom relentlessly purged from their own games. To play Tass Times in Tonetown is to die over and over and over again, usually with no warning. Walk through gramps’s dimensional gate and start to explore — bam, you’re dead because you haven’t outfitted yourself in the proper bizarre Tonetown attire. Ring the bell at an innocent-looking gate — bam, you’re dead because this gate turns out to be the front gate of the villain’s mansion. Descend a well and go west — bam, a monster kills you. Try to explore the swamp outside of town — bam, another monster kills you. The puzzles all require fairly simple actions to solve, but exactly which actions they are can only be divined through trial and error. Coupled with the absurd lethality of the game, that leads to a numbing cycle of saving, trying something, dying, and then repeating again and again until you stumble on the right move. The length of this very short game is also artificially extended via a harsh inventory limit and one or two nasty opportunities to miss your one and only chance to do something vital, which can leave you a dead adventurer walking through most of the game. As is depressingly typical of Mike Berlyn, the writing is clear and grammatically correct but a bit perfunctory, with most of the real wit offloaded to the graphics and the accompanying newspaper. And even the slick interface isn’t quite all that it first seems to be. The “Hit” icon is of absolutely no use anywhere in the game. Even more strange is the “Tell Me About” icon, which is not only useless but not even understood by the parser. Meanwhile other vital verbs still go unrepresented graphically; thus you still don’t totally escape the tyranny of the keyboard. Borrowed Time isn’t as pretty or as strikingly original as Tass Times in Tonetown, and it’s only slightly more shy about killing you, but on the whole it’s a better game, the one that gets my vote for the first one to play for those curious about Interplay’s take on the illustrated text adventure.

Thanks to the magic of pre-release hardware, Interplay got their adventures with shocking speed onto the next generation of home computers represented by the Atari ST, the Amiga, and eventually the Apple IIGS. Well before Tass Times in Tonetown, new versions of Mindshadow and Borrowed Time, updated with new graphics and, in the case of the former, the somewhat ineffectual point-and-click word lists of the latter, became two of the first three games a proud new Amiga owner could actually buy. Similarly, the IIGS version of Tass Times in Tonetown was released on the same day in September of 1986 as the IIGS itself. While the graphics weren’t quite up to the Amiga version’s standard, the game’s musical theme sounded even better played through the IIGS’s magnificent 16-voice Ensoniq synthesizer chip. Equally well-done ports of The Bard’s Tale games to all of these platforms would soon follow, part and parcel of one of Fargo’s core philosophies: “Whenever we do an adaptation of a product to a different machine, we always take full advantage of all of the machine’s new features. There’s nothing worse than looking at graphics that look like [8-bit] Apple graphics on a more sophisticated machine.”

And, lo and behold, Interplay finally finished their IBM PC-based recreation of Pebble Beach in 1986, last legacy of their days as Boone Corporation. It was published by Activision’s Gamestar sports imprint under the ridiculously long-winded title of Championship Golf: The Great Courses of the World — Volume One: Pebble Beach. It was soon ported to the Amiga, but sales in a suddenly very crowded golf-simulation field weren’t enough to justify a Volume Two. Despite their sporty founder, Interplay would leave the sports games to others henceforth. They would also abandon the adventure games that were by now becoming a case of slowly diminishing returns to focus on building on the CRPG credibility they enjoyed in spades thanks to The Bard’s Tale.

Interplay as of 1987. Even then, four years after the company’s founding, all of the employees were still well shy of thirty.

By 1987, then, Brian Fargo had established his company as a proven industry player. Over many years still to come with Fargo at the helm, Interplay would amass a track record of hits and cult touchstones that can be equaled by no more than a handful of others in gaming’s history. They would largely deliver games rooted in the traditional fantasy and science-fiction tropes that gamers can never seem to get enough of, executed using mostly proven, traditional mechanics. But as often as not they then would garnish this comfort food with just enough innovation, just enough creative spice to keep things fresh, to keep them feeling a cut above their peers. The Bard’s Tale would become something of a template: execute the established Wizardry formula very well, add lots of colorful graphics and sound, and innovate modestly, but not enough to threaten delicate sensibilities. Result: blockbuster. The balance between commercial appeal and innovation is a delicate one in any creative field, games perhaps more than most. For many years few were better at walking that tightrope than Interplay, making them a necessary perennial in any history of games as a commercial or an artistic proposition. The fact that this blog strives to be both just means they’re likely to show up all that much more in the years to come.

(Sources: The book Stay Awhile and Listen by David L. Craddock; Commodore Magazine of December 1987; Softline of January 1982, March 1982, May 1982, September 1982, January 1983, September/October 1983, and November/December 1983; Amazing Computing of April 1986; Compute!’s Gazette of September 1983; Microtimes of March 1987; Orange Coast of July 2000, August 2000, September 2000, and May 2001; Questbusters of March 1991. Online sources include: Matt Barton’s interview with Rebecca Heineman, parts 1 and 3; Barton’s interview with Brian Fargo, part 1; Digital Press’s interview with Heineman; Gamestar’s interview with Fargo; interviews with Bill Kunkel at Gamasutra, Good Deal Games, and 8-bit Rocket; “trivia” in the MobyGames page on Tass Times in Tonetown; and a VentureBeat article on Interplay. Also Jason Scott’s interview with Mike Berlyn for Get Lamp that he was kind enough to share with me. And thanks to Alex Smith for sharing the “nicheware for nerds” anecdote about Jim Levy in a comment on this blog. Feel free to download the Amiga versions of Borrowed Time and Tass Times in Tonetown from right here if you like.

I’ve finally rolled out a new minimalist version of this site for phone browsers. If you notice that anything seems to have gone sideways somewhere with it, let me know.

The Digital Antiquarian will be taking a holiday next week. Dorte and I are heading to Rome for a little getaway. But it’ll be back to business the week after, when we’ll cross the pond again at last to look at some developments in Britain and Europe.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Bill Heineman now lives as Rebecca Heineman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |

|---|

Superuser

May 1, 2015 at 12:13 pm

Root bear? :-)

Jimmy Maher

May 1, 2015 at 12:31 pm

There’s always something… weird thing is that I spelled it that way *twice*. Anyway, thanks!

Alex Smith

May 1, 2015 at 2:15 pm

Thanks for the shout out at the end there, but you did get my last name wrong. I have to admit though, Warren sounds a lot cooler than plain old Smith. ;)

Jimmy Maher

May 1, 2015 at 3:32 pm

Aw, jeez, really sorry about that. The mistake I like to make least is to get someone’s name wrong.

Alex Smith

May 2, 2015 at 6:00 pm

No worries.

matt w

May 1, 2015 at 3:11 pm

Boone instantly becomes my least favorite of all the characters you’ve written about. CHALKBOARDS 4EVA

Jimmy Maher

May 1, 2015 at 5:48 pm

Dry-erase boards, son. A disruptive, revolutionary technology in the field of cubicle living that made the world a better place. (Been watching a lot of Silicon Valley recently…)

matt w

May 2, 2015 at 1:31 am

Had they stayed in the cubicles and out of my classrooms, I would not be complaining.

Jimmy Maher

May 2, 2015 at 7:16 am

Ah, this is a personal issue with whiteboards. Now I get it.

X

May 2, 2015 at 6:47 pm

OK, I’m curious. What are the supposed advantages of chalk over whiteboards?

I can only come up with one: it’s easier to tell when you’re about to run out of chalk and office supply cabinets tend to stockpile more replacement chalk than replacement pens.

LoneCleric

May 4, 2015 at 3:14 am

Well, as one of the last members of the “chalk generation”, I would point out that, first & foremost, you can ALWAYS delete chalk from a board. It doesn’t matter that if you left something written on the board for a week, a month, or a year. At worst, you might need a little water, and ta-daaa: empty board.

Andrew Plotkin

May 1, 2015 at 4:04 pm

You can’t tell the difference between a giant owl and a giant snake? Snakes can’t fly, Jimmy. *Everybody knows that.*

I did some image searching and turned up the artist as Vicente Segrelles: http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?50731

The piece turns up with more than one title, so he probably sold it a bunch of times. Hey, money.

(Totally random trivia which I noticed while searching ISFDB: Segelles did the first US paperback cover of _The Colour of Magic_. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?37347)

Jimmy Maher

May 1, 2015 at 5:46 pm

:) Softline magazine said it was two snakes. At first I thought they were dragons, but deferred to authority and went with snakes. Also, snakes fit better with my labored Freudian joke. Obviously I need to spend more time studying the Monster Manual.

Michael Davis

May 1, 2015 at 8:12 pm

To me it looks like the snake is touching the ground, and the other guy is riding a giant condor or owl or something. So I call shenanigans on there being a depiction of flying snakes

Michael Davis

May 1, 2015 at 8:13 pm

Also, that is a f’n rad painting

matt w

May 2, 2015 at 1:25 am

My score:

“a shapely woman tied to a pole being menaced by two knights mounted on some sort of flying snakes”

“a shapely woman tied to a pole”: yes

“mounted on some sort of flying snakes”: no; the flying one is an owl, the snake has its body on the ground

“two knights”: at least half true; the one facing the camera is a stereotypical knight carrying a lance, while the one with his back to us is less certainly a knight; the battle axe is of a make that could be used by a knight, the shield isn’t quite as pointy as I expect from this sort of depiction of a knight, but what is truly atypical of a knight is the, um, distinct lack of armor

“being menaced”: not by both of them surely? At first I thought that Owly was flying in and menacing her while Snakey was defending her but given the “tied to a pole” thing it makes more sense that Snakey is holding her prisoner and Owly is flying in to rescue her, especially since the tied appears to be rising, and this makes more sense of the roles one would expect from the one who is a knight and the one who is not a knight

However I do not recommend that you change a word of your original sentence.

I would also say that there’s a sort of equal opportunity we do not always see in this sort of art, in that we have a much better view of the man’s buttocks than the woman’s.

matt w

May 2, 2015 at 1:28 am

An image search for Vicente Segrelles suggests that the last point does not universally hold for him.

Jimmy Maher

May 2, 2015 at 7:23 am

I like this one a lot: http://lccomics.narod.ru/image/comic/vicente_segrelles/vincent_segrelles_giantslayer.jpg. At least the right arm and legs are well-protected. I like the way he draws breasts like balloons mounted on his models’ chests, sort of the way kids with no experience with actual breasts draw them.

Peter Piers

January 15, 2016 at 7:32 pm

Jimmy, NSFW on that last image would have been appreciated. Thankfully I got lucky. :)

Andy B

May 3, 2015 at 1:49 am

Picking up from where Andrew Plotkin left off, Google seems to be saying that this painting was originally part of Segrelles’s own long-running comics series, “El Mercenario,” which astonishingly seems to be done in exactly this style, and in oils, on every page! It looks to consist of a continuous succession of similar dragon + damsel – clothes scenarios, but fully fleshed out.So to speak. So it seems entirely possible that this particular image is in fact part of an actual narrative continuity, and that some of our burning questions about what’s going on here might have official and correct answers. Oddly enough. In any case, it’s certainly El Mercenario coming to the rescue on that owl.

rockersuke

May 4, 2015 at 1:08 am

Almost! El Mercenario actually used some mix of flying bat-lizard thing :-) I recognised Demon’s Forge cover art at first sight as It happened to be the cover of spanish CIMOC comics magazine #2 (see here), which I used to read in my teen years (and where Mercenario was first serialized). It also reached the States in 1982, where it was published in Heavy Metal magazine. Other than the flying beast detail, your assumptions are right: it was rescuing some half/totally naked lady tied to something most of the time :-)

Some pics of its very first edition:

Image 1

Image 2

Image 3

Incidentally, using previously existing ilustration artwork as video-games package art was common practice in the 80’s spanish gaming market. As an example, this other CIMOC magazine cover was soon after used as cover-art for “La Aventura Espacial”, a popular menu-based spanish text adventure by Aventuras AD as well as at least a couple of some other unrelated ci-fi novels.

Image 4

While the story of the spanish text adventure late 80’s scene might be out of scope for this blog, the case of Aventuras AD might be of interest for Jimmy Maher as it is strongly related to the whereabouts of Gilsoft member Tim Gilberts right after the events told in the post dedicated to the Quill. . If you feel curious and can read some spanish you can take a look at this post from my blog where the recent rescue and preservation of the custom-made tool used at that company is related.

(going to re-read some of my surviving comics from the happy 80’s :-) )

Ian Schmidt

May 1, 2015 at 6:31 pm

Heineman was one of the true masters of the IIGS. Her games always went above and beyond on that platform, and she kept making them well after there was any sane marketing reason to do so (which resulted in Interplay shipping Dragon Wars for the machine right as Apple was pulling the plug in 1993 – funny how the 16-bit machines all died within a few months of each other). One of my top 5 game programming heroes, and her trademark hamburger-related Easter Eggs were always amusing.

Adam Huemer

June 23, 2025 at 6:14 pm

*his

Michael Davis

May 1, 2015 at 8:20 pm

“A bunch of pixeish”

Scott M. Bruner

May 1, 2015 at 11:00 pm

One question about The Bard’s Tale. You mention how the name was changed to accentuate that character. My historical understanding was that the title of the first game was “Tales of the Unknown Vol 1: The Bard’s Tale,” with the idea that the next was going to be “Tales of the Unknown Vol2: The Destiny Knight,” but that EA demanded they keep the Bard’s Tale moniker to make sure people understood what the next game was a sequel to. (And probably rightly, I don’t remember anyone referring to the game on release as “Tales of the Unknown 1”)

So many characters from the early games have disappeared – I’m happy Brian Fargo is still an active contemporary and passionate about what he does. I’m sad, though, that he decided against bringing Rebecca Heineman back for BT 4 *(although she has tweeted that is going to announce a Kickstarter for Dragon Wars 2 as well) , which I am anxiously waiting to support.

Jimmy Maher

May 2, 2015 at 7:29 am

Basically right, except that the second game was to be called The Arch-Mage’s Tale. The idea was that each in the series would highlight a different class. But yeah, everyone simply knew the first game as The Bard’s Tale, and it would have been crazy not to have capitalized on that name recognition.

Scott M. Bruner

May 1, 2015 at 11:20 pm

One other comment – Interplay’s Neuromancer, a point-and-click adventure based on the William Gibson novel, was also very impressive.

Not only because it provided a fairly compelling take on Gibson’s cyberpunk world including a surreal recreation of cyberspace where the player had to battle artificial intelligences using an array of hacking software as weapons, but also because it was simply one of the better adventures of the time, in a market I remember being pretty much owned/saturated by SOL.

It’s definitely worth a spin for anyone interested in classic Interplay (or classic point’n’clickers).

Jimmy Maher

May 2, 2015 at 7:26 am

Definitely will be covering this one in the future…

Markus Peter

May 3, 2015 at 9:01 pm

I loved the game and its strange combination of adventure and hacking simulation. This was my first encounter with William Gibson – I remember buying the book when I encountered a dead end in the game, just to know the end of the story, only to notice later on that both were only loosely related when I finally managed the game.

Great where the days, when you couldn’t google a walkthrough. Nowadays, I simply wouldn’t have the patience anymore.

iPadCary

May 13, 2015 at 12:14 pm

The Commodore64 version plays a sample of DEVO’s “Some Things Never Change” in the intro, but the Amiga version doesn’t. Go figure.

Marie Fargo-Sork

May 2, 2015 at 8:08 pm

Brian is still a wonderful business man

Nate

May 3, 2015 at 1:17 am

The story of Cranford holding the BT1 disk hostage is disputed by Cranford. He claims he wanted the contract he was presented to reflect the verbal deal, and that they eventually negotiated something which wasn’t the original deal anyway.

http://www.rpgcodex.net/content.php?id=9163

This is also in Matt Barton’s book on CRPGs (recommended).

http://www.amazon.com/Dungeons-Desktops-History-Computer-Role-Playing/dp/1568814119

Jimmy Maher

May 8, 2015 at 9:36 am

From the interview you linked to:

“Now, this story that I held a disk hostage to extort someone – that didn’t happen, I would never do that. Sitting on the source code until the deal I was promised was finally put in writing and honored – that is possible. I honestly can’t remember.”

Cranford seems to be trying to draw a distinction here that’s really no distinction at all. Using softer language than “extort” or “hold hostage” doesn’t really change the substance of the case.

I would suspect that the source of the difficulties came from a confusion about just what sort of “promise” had been made to Cranford. At least as he tells the story today, Fargo believed the plan to be to pay Cranford in stock and to use the royalties from The Bard’s Tale — which looked to have the potential from very early on to be the big hit it did indeed become — to “grow the company.” Cranford seems to have expected from the beginning the royalties he did eventually receive on the final contract. I suppose there’s a depressing lesson here about the need to put things in writing as soon as money is involved, even if you’re working with one of your best friends. For Cranford personally, there’s also perhaps another lesson: as Fargo has noted wryly, he would have been better off in the long run to forgo short-term profit and take the stock, which turned into quite a winner thanks largely to his own games.

William Hern

May 8, 2015 at 3:26 pm

Fascinating article Jimmy – great research!

One small typo in the second “Tass Times” paragraph: “… you gramps’s dog Spot” should be “… your gramps’s dog Spot”.

Jimmy Maher

May 10, 2015 at 11:20 am

Thanks!

iPadCary

May 13, 2015 at 12:15 pm

Happy Birthday, Inge Lehmann.

John G

May 23, 2015 at 6:21 pm

While I love your research and history on these blog entries, it seems like every time I stop by, some poor IF pioneer is being called a bad writer.

Poor Mike Berlyn is fighting cancer and used to write novels like “The Integrated Man.” Does it really behoove anyone to call his prose depressingly perfunctory or whatever? Or to try and bring Steve Meretzky down a notch? It’s not a zero-sum thing, “Trinity” and “AMFV” are both allowed to be good.

Here if anyone is interested is a fundraiser to help Berlyn.

http://www.gofundme.com/skb9h3c

Peter Piers

January 15, 2016 at 7:49 pm

Unfair. Maher devoted a post to raising awareness of Berlyn’s condition. Also, Maher does a superb job of explaining what he feels is sub-par about each writer, rather than merely throwing up empty critiques. If you agree with Maher’s explanations, you agree with his views; if you don’t, then you don’t.

Also, beware of generalisations. Berlyn’s prose is called “perfunctory” in the context of Tass Times.

Guffaw

December 31, 2015 at 3:11 am

“; Fargo’s days of scrabbling after any work he could find looked to be over for a long, long time to come.”

Perhaps “looked” should be “seemed” ? :)

Jimmy Maher

December 31, 2015 at 8:24 am

No, “looked” works here. A bit more colloquial, but we’re not *that* high-falutin’ around here. ;)

Peter Ferrie

February 7, 2016 at 5:46 am

Minor thing – the proper name is “The Tracer Sanction”, rather than just “Tracer Sanction”.

Jimmy Maher

February 7, 2016 at 8:39 am

Thanks!

DZ-Jay

March 14, 2017 at 11:09 am

Since you mentioned the mobile phone version of the site in this article, I’d like to make a suggestion: it would be ideal if the “next” and “previous” article links were repeated at the top and bottom.

Sometimes while on the road, I want to catch up where I left off from my PC, and find myself having to hit “next” many times in order to advance to a later article. Your current mobile layout forces me to scroll to the bottom of the article (which, coincidentally is not the bottom of the page, but somewhere in between, making it that much harder to find precisely) in order to get to the navigation buttons.

Other than that, thanks for a great article.

-dZ.

John Elliott

November 22, 2017 at 3:59 pm

I’ve been taking a look at how Mindshadow was implemented. At least on the Spectrum, it consists of five zones, each zone comprising up to 16 rooms* placed on a 6×6 grid. The five zones are the island, the pirate ship, London, Luxembourg and the second floor of the hotel. It’s an interesting constraint, and one I haven’t seen in other game engines. I haven’t played Tracer Sanction, that never having made it to the Spectrum, so I don’t know if its engine operates in the same way.

* Up to 16 unique rooms, that is; multiple copies of a room are allowed, which is how the mazes are implemented.

Jimmy Maher

November 24, 2017 at 2:52 pm

The complete source is available in the Strong Museum’s Brian Fargo archive, if you ever make it up to Rochester.

Wolfeye M.

September 15, 2019 at 6:28 pm

Um. Unless my eyes deceive me… There’s a giant bird and the snake isn’t flying. There’s a pole with a girl tied to it, though.

Wolfeye M.

September 15, 2019 at 6:54 pm

Ah, Interplay. They’re one of my favorite game companies. Years down the road from the time mentioned in this article, they were involved with my favorite Star Trek game series, Starfleet Command. They also did the original Fallout games. They put the fun into the post-apocalyptic world. Nice to read about how they got started.

Costa

December 24, 2019 at 1:10 am

Fascinating stuff! Any chance you could follow this up with the later years of Interplay (Star Trek, Fallout) up until it’s demise?

Jimmy Maher

December 24, 2019 at 8:47 am

https://www.filfre.net/tag/interplay/

Ben

September 17, 2022 at 7:57 pm

pixeish -> pixieish

Electronics Arts -> Electronic Arts

to continuing doing -> to continue doing

Dashiell Hammet -> Dashiell Hammett

nichware -> nicheware

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2022 at 6:35 am

Thanks!

_RGTech

June 10, 2024 at 7:13 pm

“and needing product to get him started” -> needing a product?

(maybe it’s not necessary, but that would make that sentence a bit easier to read)

Jimmy Maher

June 12, 2024 at 1:36 pm

Thanks!