If you look at the way critics describe Lovecraft … they often say he’s purple, overwritten, overblown, verbose, but it’s un-putdownable. There’s something about that kind of hallucinatorily intense purple prose which completely breaches all rules of “good writing”, but is somehow utterly compulsive and affecting. That pulp aesthetic of language is something very tenuous, which all too easily simply becomes shit, but is fascinating where it works.

– China Miéville

One of Lovecraft’s worst faults is his incessant effort to work up the expectations of the reader by sprinkling his stories with such adjectives as “horrible,” “terrible,” “frightful,” “awesome,” “eerie,” “weird,” “forbidden,” “unhallowed,” “unholy,” “blasphemous,” “hellish,” and “infernal.” Surely one of the primary rules for writing an effective tale of horror is never to use any of these words — especially if you are going, at the end, to produce an invisible whistling octopus.

— Edmund Wilson

So that was what these lekythoi contained; the monstrous fruit of unhallowed rites and deeds, presumably won or cowed to such submission as to help, when called up by some hellish incantation, in the defence of their blasphemous master or the questioning of those who were not so willing?

— H.P. Lovecraft, “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward”

H.P. Lovecraft is what people like to call a “problematic” writer. For many, the quote just above is all they need to know about him: a jumble of wild adjectives seemingly thrown into the air and left where they fell, married to a convoluted tangle of dependent clauses, all ending in a non-sequitural question mark. Lovecraft’s more fervent admirers sometimes say that he is a “difficult” writer, whose diction must be carefully unpacked, not unlike that of many other literary greats. His detractors reply, not without considerable justification, that his works don’t earn such readerly devotion, that they remain a graceless tangle even after you’ve sussed out their meaning. And that’s without even beginning to address the real ugliness of Lovecraft, the xenophobia and racism that lie at the core of even his best-regarded works. Lovecraft, they say, is simply a bad writer. Full stop.

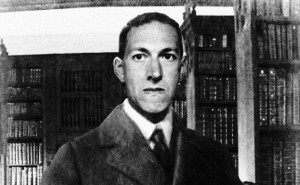

Well, they’re mostly right. Lovecraft is in most respects a pretty bad writer. He is, however, an otherwise bad writer who somehow tapped into something that many people find deeply resonant of the proverbial human condition, not only in his own time but perhaps even more so in our own. Despite his clumsy prose and his racism and plenty of other sins, his stature has only continued to grow over the decades since his death in poverty and obscurity in 1937 at age 46. This man who himself believed he died a failure, who saw his work published only in lurid pulp magazines with names like Weird Tales and never had the chance to walk into a bookstore and see a book of his own on the shelf, now has a volume in the prestigious Library of America series. His literary influence, at least within the realm of fantastical fiction, has been almost incalculable. Stephen King may have sold hundreds of millions more books, but it’s Lovecraft who’s most often cited to be the most influential single practitioner of horror fiction of the twentieth century. In popular culture too he’s everywhere, from 1979’s classic science-fiction thriller Alien to 2014’s critically acclaimed first season of True Detective. The alien monstrosity Cthulhu, his most famous creation, now adorns tee-shirts, coffee mugs, and key rings; you can even take him to bed with you at night in the form of a plush toy. For a lifelong atheist, Lovecraft has enjoyed one hell of an afterlife.

Perhaps most surprising of all is Lovecraft’s stature as one of the minor deities of ludic fictions, living on a plane only just below the Holy Trinity of Tolkien, Lucas, and Roddenberry. He was an avowed classicist who found the early twentieth century far too modern for his tastes, who believed that he’d been born 200 years too late. He disliked technology as much as he did most other aspects of modernity, wrote in an archaic diction that was quite deliberately centuries out of date even in his own day, and in general spent his entire life looking backward to an idealized version of the past. Yet there’s his mark stamped implicitly or explicitly all over gaming — gaming with its cult of the new, its fetishization of technology, its unquenchable thirst for more gigabytes, more gigahertz, more pixels. It’s a strange state of affairs — but, then again, one of the Holy Trinity itself was a musty old pipe-smoking Oxford professor of philology who was equally disdainful of modern life.

At any rate, we’re just getting to the point in this little history of gaming where Lovecraft starts to become a major factor. Therefore it seems appropriate to spend some time looking back on his life and times, to try to understand who he was and what it is about him that so many continue to find so compelling.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft was born his parents’ first and, as it would transpire, only child into comfortable circumstances in Providence, Rhode Island, on August 20, 1890. His father was a traveling sales representative for a local silversmith, his maternal grandfather an entrepreneur and industrialist of considerable wealth and influence. The specter of madness, destined to hang constantly over Lovecraft’s own life as it would that of so many of his fictional protagonists, first raised its head when he was three years old: his father had a complete nervous breakdown on a sales trip to Chicago, likely caused by syphilis. He never recovered his sanity, and young Howard never saw his father again after his breakdown; he died in an asylum within five years.

Lovecraft’s mother was also of what they used to call a “nervous disposition,” alternately encouraging, coddling, smothering, domineering, and belittling him. Still, life as a whole was pretty good for much of his childhood. Mother and son lived with his grandfather and two aunts in a rambling old house with a magnificent library and a cupola outfitted as his personal clubhouse, complete with model trains, armies of lead soldiers, and all the other toys a boy could want. While he showed little interest in children his own age and they in turn showed little in him, Lovecraft would come to remember his childhood as the best period of his life. The family treated him as a prodigy, indulging his interests in chemistry and astronomy and clapping heartily when he read to them his first stories and poems — and, it must be said, not without reason; one of his poems, a gloss on The Odyssey composed when he was just seven years old, consisted of 88 lines of meticulously correct iambic heptameter.

But then, on March 24, 1904, came the event that Lovecraft would always reckon the greatest tragedy of his life. His grandfather died on that date, leaving behind a financial situation that proved, thanks to a recent string of losses by his business interests, far worse than anyone in his family had anticipated. Lovecraft and his mother were forced to move from the spacious ease of the family homestead, which had come complete with a retinue of liveried servants, into a cramped little duplex, where they’d have to fend for themselves. The young Lovecraft, already extremely class-conscious, took the decline so badly that he considered suicide. He compensated by claiming ever more stridently, on the basis of little real evidence, to be the latest of a long line of “unmixed English gentry.” Given his already burgeoning obsession with racial and familial purity, that was a wealth far more important than mere money.

Despite his prodigious childhood, Lovecraft’s academic career petered out anticlimactically. For some years he had hoped to become an astronomer, but when the time came to think about university he elected not to even attempt the entrance exam, fearing that his math skills weren’t up to the test. Avoiding the stigma of failure by not even trying would continue to be the pattern of much of his life. Arrogant yet, as arrogant people so often are, extremely insecure at heart, he preferred to adopt the attitude of the wealthy gentry of old whom he so admired, waiting in his increasingly shabby ivory tower for opportunities to come to him.

His academic career was over before it had really begun, but Lovecraft considered workaday employment to be beneath him. He lived until age 28 under the thumb of his mother, subsisting on the slowly dwindling remains of his grandfather and father’s inheritances and the largess of other family members. His principal intellectual and social outlet became what was known at the time as “amateur journalism”: a community of writers who self-published newsletters and pamphlets, forerunners to the fanzines of later years (and, by extension, to the modern world of blogging). A diligent worker who was willing to correspond with and help just about anyone who approached him — a part of his affected attitude of noblesse oblige — Lovecraft also had lots of time and energy to devote to what must remain for most practitioners a hobby. His star thus rose quickly: he became vice president of the United Amateur Press Association, the second largest organization of its kind in the country, in 1915, and its president in 1917, whilst writing prolifically for the various newsletters. His output during this period was mostly articles on science and other “hard” topics, along with a smattering of stilted poetry written in the style of his favorite era, the eighteenth century. He also began the habit of copious and voluminous letter writing, largely to fellow UAPA members, that he would continue for the rest of his life. By the time of his death he may have written as many as 100,000 letters, many running into the tens of pages — a staggering pace of eight or nine often substantial letters per day in addition to all of his other literary output.

By the time he was serving as president of the UAPA, his mother, always high-strung, was behaving more and more erratically. She would run screaming through the house at night believing herself to be chased by creatures from her nightmares, and suddenly forget where she was and what she was doing at random times during the day. She was quite possibly suffering from the same syphilis that had killed her husband. At last, on March 13, 1919, her family committed her to the same mental hospital that had housed her husband; also like her husband, she would die there two years later after a botched gall-bladder surgery. Lovecraft was appropriately bereaved, but he was also free. Within reason, anyway: unable to cook or do even the most basic housekeeping chores and unwilling to learn, and having no independent source of income anyway, he wound up living with his aunts again.

Around the same time, he began to supplant his nonfiction articles and his poetry with tales of horror, drawing heavily on the style of his greatest literary idol, Edgar Allan Poe, as well as contemporary adventure fiction, his family’s history of madness, and the recurring nightmares that had haunted him since age six. While the quality of his output seesawed radically from story to story during this period, as indeed it would throughout his career, he wrote some of his most respected tales in fairly short order, such as “The Music of Erich Zann” and “The Rats in the Walls.”

That last story in particular evokes many of the themes and ideas that would later come to be described as quintessentially Lovecraftian. An aging American industrialist chooses to retire to his family’s ancestral home in England. He builds his new family seat on the ruins of the old, a place called Exham Priory which was abandoned during “the reign of James the First” when one of the sons murdered his parents and siblings and fled to Virginia to found the current branch of the family tree. Three months after these events, as local legend would have it, a flood of rats had poured forth from the derelict building, devouring livestock and a few of the villagers. Since then the site has been one of ill repute, never occupied or rebuilt and avoided conscientiously by the locals. Dismissing it all in classic horror-story fashion, our elderly hero rebuilds the place and moves in, only to be awakened night after night by the sound of thousands of rats scurrying behind the walls, rushing always downward toward an altar in the cellar, a relic from an ancient Druidic temple that apparently once existed on the site. Working with some associates, he finds the entrance to a secret underground labyrinth beneath the altar, where his ancestors practiced barbaric rites of human sacrifice and cannibalism; it was apparently his discovery of and/or attempted initiation into the familial cult that led that one brave son to murder his family and flee to the New World. Alas, our hero proves not so strong. The story ends, as so many Lovecraft stories do, in an insane babble of adjectives, as the protagonist goes crazy, kills, and eats one of his comrades. He is telling his story, we learn at the end, from the madhouse.

Many Lovecraft stories deal similarly in hereditary evil and madness, the sins of the father being visited upon the helpless son. That seems paradoxical given that he was an avowed atheist and materialist, but nevertheless is very much in keeping with his equally strong belief in the power and importance of bloodlines. There are obvious echoes of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” in “The Rats in the Walls” — so obvious that Lovecraft, admittedly not exactly the most self-aware of writers, could hardly fail to be aware of them. Yet I think a comparison of the two stories also does a great deal to point out the differences between the two writers. Poe focuses on inner, psychological horrors. In “The Tell-Tale Heart,” it’s his protagonist’s guilt over a senseless murder he himself committed that leads him to hear the beating of his victim’s heart under the floorboards of his house, and that finally drives him mad. Whatever else you can say about his plight, it’s a plight he created for himself. But the evil in “The Rats in the Walls” is an external evil in the face of which psychology is meaningless, guilt or innocence irrelevant, and the narrator helpless. Lovecraft brings us to shudder not for his characters, who are so thin as to be impossible to really care about, but for humanity as a whole. Nihilism on this cosmic scale was something new to horror fiction; it’s the bedrock of his claim to literary importance.

Lovecraft’s big break, such as it was, came in 1923 when one of his young protégés told him of a new paying magazine called Weird Tales that was just starting up and was thus eager for submissions. Why, they asked, didn’t he submit some of his stories?

The letter that Lovecraft attached along with his initial submission of five stories finds him still affecting the persona of an English gentleman of leisure who likes to amuse himself with a bit of scribbling now and again, who doesn’t really care all that much whether Weird Tales is interested or not.

Having a habit of writing weird, macabre and fantastic stories for my own amusement, I have lately been simultaneously hounded by nearly a dozen well-meaning friends into deciding to submit a few of these Gothic horrors to your newly founded periodical … I have no idea that these things will be found suitable, for I pay no attention to the demands of commercial writing … the only reader I hold in mind is myself …

The magazine did accept all five of them for the handsome fee of 1.5 cents per word, beginning a steady if far from lucrative relationship that would last for the rest of Lovecraft’s life. Weird Tales would remain always far from the top of the pulps, selling a bare fraction of what the biggest magazines like Argosy All-Story Weekly and Black Mask sold. Yet even among its stable of second-tier authors Lovecraft was not particularly prominent or valued. In over a decade of writing for Weird Tales, he wasn’t once granted top billing in the form of a cover story. Indeed, many of his submissions, including some that are regarded today as among his best work, were summarily rejected.

The February 1928 issue of Weird Tales that included Lovecraft’s most famous story. As always, it didn’t make the cover.

It was shortly after his stories started appearing in Weird Tales that Lovecraft embarked on the one great adventure of his life. In March of 1924 this confirmed bachelor, who had never before expressed the slightest romantic interest in a woman, shocked family and acquaintances alike by abruptly moving to New York City to marry Sonia Greene, one of his UAPA correspondents. Just to make it all still more bizarre, she was a Jew, one of the groups of racial Others whom he hated most. But anyone who thought that his wife’s ethnicity might reflect a softening of his racism was soon proved wrong. He instructed Sonia that she should ensure that any gatherings she arranged be made up predominantly of “Aryans,” and persisted in excoriating her ethnicity, often right in front of her. The marriage soon ran into plenty of other problems. She was loving and affectionate; he, she would later claim, never once said the words “I love you” to her. She had a healthy interest in sex; he had none — indeed, found it repulsive. (He had an “Apollonian aesthetic,” she a “Dionysian,” he would later say in his pompous way.)

The couple separated within a year, Lovecraft renting a single large room for himself in Brooklyn Heights, a formerly wealthy area of New York now come down in the world, full of rooming houses catering to transients and immigrants. That last in particular always spelt trouble for Lovecraft. He poured his bile into “The Horror at Red Hook.” One of his uglier stories, it’s set in the Red Hook district of Brooklyn, a neighborhood with a similar history to that of Brooklyn Heights. It reads like a bigot’s vision of Paradise Lost.

Its houses are mostly of brick, dating from the first quarter to the middle of the nineteenth century, and some of the obscurer alleys and byways have that alluring antique flavour which conventional reading leads us to call “Dickensian”. The population is a hopeless tangle and enigma; Syrian, Spanish, Italian, and negro elements impinging upon one another, and fragments of Scandinavian and American belts lying not far distant. It is a babel of sound and filth, and sends out strange cries to answer the lapping of oily waves at its grimy piers and the monstrous organ litanies of the harbour whistles. Here long ago a brighter picture dwelt, with clear-eyed mariners on the lower streets and homes of taste and substance where the larger houses line the hill. One can trace the relics of this former happiness in the trim shapes of the buildings, the occasional graceful churches, and the evidences of original art and background in bits of detail here and there—a worn flight of steps, a battered doorway, a wormy pair of decorative columns or pilasters, or a fragment of once green space with bent and rusted iron railing.

From this tangle of material and spiritual putrescence the blasphemies of an hundred dialects assail the sky. Hordes of prowlers reel shouting and singing along the lanes and thoroughfares, occasional furtive hands suddenly extinguish lights and pull down curtains, and swarthy, sin-pitted faces disappear from windows when visitors pick their way through.

After describing his unhappiness in New York to his aunts with increasing stridency — he said he awoke every morning “screaming in sheer desperation and pounding the walls and floor” — Lovecraft got from them a railway ticket and an invitation to come back home at last in April of 1926. His two-year adventure in adulthood having ended in failure, he resumed what even his most admiring biographers acknowledge to be essentially a perpetual adolescence.

Back in Providence, Lovecraft wrote his most anthologized, most read, most archetypal, most influential, and arguably simply best story of all: “The Call of Cthulhu.” Its opening lines are the most famous he ever wrote, and for once relatively elegant and to the point, a mission statement for cosmic horror.

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

The narrator of “The Call of Cthulhu” is an intellectual gentleman, apparently an anthropologist of some stripe or other, who stumbles upon a sinister cache of documents whilst serving as executor of his grand-uncle’s estate following the latter’s death under somewhat mysterious circumstances. An epistolary tale in spirit if not quite in technical form, the bulk of its length consists of our narrator explaining what he found in that initial cache as well as the further research to which it leads him. He gradually uncovers evidence of a sinister global cult, older than antiquity, which worships Cthulhu, an extraterrestrial entity of inconceivable power. Cthulhu sleeps entombed somewhere beneath the Pacific Ocean, waiting until “the stars are right,” when he will rise again to awaken his even more powerful comrades — the so-called “Great Old Ones” — and rule the world. Non-converts like our benighted narrator and his grand-uncle who learn of the cult’s existence tend not to live very long; it apparently has a very long reach. Importantly, however, it’s also strongly hinted that the cult may be in for a rude surprise of its own when Cthulhu does finally awaken. He and the Great Old Ones will likely crush all humans as thoughtlessly as humans do ants on that day when the stars are right again.

In only one respect is “The Call of Cthulhu” not archetypal Lovecraft: it has a relatively subdued climax in comparison to the norm, with our narrator neither dead nor (presumably) insane but rather peeking nervously around every corner, waiting for the cult’s inevitable assassin to arrive. This is doubtless one of the things that make it so effectively chilling. Otherwise all of the classic tropes, or at least those that didn’t already show up in “The Rats in the Walls,” are here: locales spanning the globe; forbidden texts; non-Euclidean alien geometries “loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours.” There’s the affectedly archaic diction: “legends” becomes “legendry”; “show” becomes “shew.” There’s lots of words that you’ll only find in Lovecraft, to such an extent that you know as soon as you see one of them that you’re reading either him or one of his imitators: “eldritch,” “Cyclopean,” “daemonic.” There’s the way that every single person or document talks in the exact same voice and diction. (This applies even to an extract from The Sydney Bulletin, which describes the crew of a ship as “a queer and evil-looking crew of Kanakas and half-castes.”) And yes, this being Lovecraft, the usual racism and horror of miscegenation is also all over the place: the cult makes its outposts not with the upright Aryan races but with the “debased,” “mongrel” peoples of the earth. Almost as notable is what is conspicuously missing, here as well as elsewhere in the Lovecraft oeuvre: humor, women, romance, beauty that isn’t somehow “blasphemous” or “daemonic.” Come to think of it, about 95 percent of life’s rich pageant. Some writers like Shakespeare and Tolstoy enfold the whole world of human experience, while others focus obsessively on one tiny corner of it. Lovecraft is definitely among the latter group.

Many of Lovecraft’s later stories continued to explore what came to be known as the “Cthulhu Mythos,” sometimes in the form of novellas rather than short stories. Always generous with his friends and correspondents, he also happily allowed other writers to play with his creations. Thus the Mythos as we’ve come to know it today, as a shared universe boasting contributions from countless sources — many of them, it must be said, much better writers than Lovecraft himself — was already well into its gestation before his death. Whatever else you can say about Lovecraft, his complete willingness to let others share in his intellectual property is refreshing in our current Age of Litigation. It’s one of the principal reasons that the Mythos has proved to be so enduring.

When not writing his stories or his torrents of letters, Lovecraft spent much of the last decade of his life traveling the Eastern Seaboard: as far south as Florida, as far west as Louisiana, as far north as Quebec. Preferring by his own admission buildings to people, he would invariably seek out the oldest section of any place he visited and explore it at exhaustive length, preferably by moonlight. Broker than ever, he often stayed with members of his small army of correspondents, who also took it upon themselves to feed him. Otherwise he often simply went hungry, sometimes for days at a time. Paul Cook, one of his few local friends, was shocked at the state in which he returned to Providence from some of his rambles: “Folds of skin hanging from a skeleton. Eyes sunk in sockets like burnt holes in a blanket. Those delicate, sensitive artist’s hands and fingers nothing but claws.”

Those friends and correspondents of his, more numerous than ever, were an interesting lot. They now included among them quite a number of other writers of pulpy note, some of them far more popular with inter-war readers than he: Robert E. Howard (creator of Conan the Barbarian), Clark Ashton Smith (the outside writer who first and most frequently played in the Cthulhu Mythos during Lovecraft’s lifetime), Fritz Leiber (creator shortly after Lovecraft’s death of the classic fantasy team of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser), Robert Bloch (author many years later of Psycho). Those last two, as well as many or most of Lovecraft’s other regular correspondents, were notable for their youth. Many, like Bloch, were still in their teens. The picture below shows Lovecraft on a visit to the family of another of his young friends in Florida in 1935. Robert Barlow had just turned 17 at the time. It’s an endearing image in its way, but it’s also a little strange — even vaguely pathetic — when you stop to think about it. What should this 45-year-old man and this 17-year-old boy really have to share with one other?

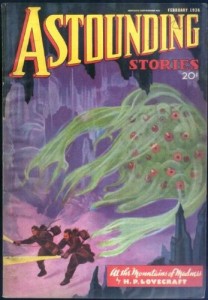

Ironically, Lovecraft died just as his career seemed to be on the upswing. In 1936 he received $600, the most he’d ever been paid at once for his writing and a small fortune by his meager standards, for two novellas (At the Mountains of Madness and The Shadow Out of Time) that were published by the prestigious (by pulp standards) Astounding Science Fiction. This marked a major step up from the perpetually near-bankrupt Weird Tales. Best of all, both novellas made the cover, signaling what could have been the start of a steady relationship with a magazine that valued him much more than Weird Tales ever had, that may have finally allowed him to earn a real living from writing. But it wasn’t to be. On February 27, 1937, after weeks of excruciating stomach pain, he visited a doctor for the first time in years, who determined that cancer of the small intestine and acute kidney disease were in a race to see which could kill him first. He died on March 15.

The upswing in Lovecraft’s literary fortunes that began with his publication in Astounding proved oddly unaffected by his death. In 1939 August Derleth and Donald Wandrei formed Arkham House — named after the fictional New England city, a stand-in for Providence, where Lovecraft set many of his stories — to preserve his works in book form. A long, convoluted series of copyright disputes arose almost immediately, initially between Lovecraft’s young friend Robert Barlow, whom he had named as executor of his estate, and Darleth and Wandrei, who claimed to have been bequeathed the rights to his stories by his family. This tangle has never been entirely resolved, but most people today simply act as if Lovecraft’s stories are all in the public domain, and to the best of my knowledge no one has ever been sued for it.

Edmund Wilson’s infamous 1945 hatchet job for The New Yorker, from which I quoted to begin this article, is entertaining but not terribly insightful, and must have been disheartening on one level for fans of Lovecraft, especially as it set the tone for discussion of him in high-brow literary circles for decades to come. On the other hand, though, the very fact that Wilson, the country’s foremost literary critic at the time, felt the need to write about him at all is a measure of how far he had already come in the eight years since his death. Since then Lovecraft has continued to grow still more popular almost linearly, decade by decade. He long since became one of those essential authors that anyone seriously interested in the genres of fantasy, science fiction, or horror simply has to read, and if the recent success of True Detective is anything to go by he’s not doing too badly for himself in mainstream culture either. As I write this article today I see that not only “Lovecraft” but also “Cthulhu” are included in the Firefox web browser’s spelling dictionary. What more proof can one need of the mainstreaming of the Mythos?

But just what is it about this profoundly limited writer that makes his work so enduring? Well, I can come up with three reasons, one or more of which I believe probably apply to most people who’ve read him — those, that is, who haven’t run screaming from the horrid prose.

The first and most respectable of those reasons is that when he wrote “The Call of Cthulhu,” his one stroke of unassailable genius, Lovecraft tapped into the zeitgeist of his time and our own. We should think about the massive shift in our understanding of our place in the universe that was in process during Lovecraft’s time. In the view of the populace at large, science had heretofore been a quaint, nonthreatening realm of gentlemen scholars tinkering away in their laboratories to learn more about God’s magnificent creation. Beginning with Darwin, however, all that changed. Humans, Darwin asserted, were not created by a divine higher power but rather struggled up, gasping and clawing, from the primordial muck like one of Lovecraft’s slimy tentacled monsters. Soon after the paradigm shift of evolution came Einstein with his theories about space and time, which claimed that neither were anything like common sense would have them be, that space itself could bend and time could speed up and slow down; think of the “loathsome non-Euclidean geometry” of Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones. And then came our first inklings of the quantum world, the realization that even the comforting regularity of Newtonian physics was a mere facade spread over the chaos of unpredictability that lay beneath. The world seemed to be shifting beneath humanity’s feet, bringing with it a dawning realization that’s at the heart of the embodiment of existential dread that is Cthulhu: that we’re just not that important to anyone or anything; indeed, that it’s difficult to even express how insignificant we are against the vast sweep of the unfeeling cosmos. I believe that our collective psyche still struggles with the ramifications of that realization today. Some cling ever tighter to traditional religion (it’s interesting to note that fundamentalism, in all its incarnations, is a phenomenon that postdates Darwin); some spend their lives trying to forget it via hedonism, career, social media, games (hey, I resemble that remark!); some, the lucky ones, make peace with their insignificance, whether through Nietzschian self-actualization, spirituality, or something else. But even for them, I believe, persists somewhere that dread and fear of our aloneness and insignificance, born of the knowledge that a rogue asteroid — or a band of inconceivably powerful and malevolent aliens — could wipe us all out tomorrow and no god would save us. It’s this dread and fear that Lovecraft channels.

That’s the philosophical argument for Lovecraft’s importance, and I do think it’s a good one. At the same time, though, it’s hardly a full explanation of why so many of us continue to enjoy — yes, enjoy — reading Lovecraft even after he’s beaten his one great idea comprehensively into the ground over the course of dozens of tales. We also read Lovecraft, ungenerous and even voyeuristic as it may sound, because we’re fascinated by the so obviously troubled personality that created them. In short, we want to know just what the hell is up with Lovecraft, this man who fancied himself an independent, strong-minded gentleman scholar yet is actually terrified of just about every damn thing in the universe. Various people have advanced various theories as to what in fact was up with Lovecraft. Some, noting his inability to express any other emotion than terror and, most of all, disgust — which he admittedly does do very well — have said that he must have been on the autism spectrum. Others, noting his habit of surrounding himself with young male admirers and his occasional habit of describing their appearance in rather, shall we say, idealized terms, have questioned whether he was a closeted homosexual — quite possibly closeted even from himself. In the end, though, all such theories end up feeling unsatisfying and anachronistic.

What is clear is that the Lovecraft we meet in his fiction is a walking, talking bundle of neuroses and phobias, disgusted especially by the seething biological physis that is life itself. Most of all, he’s disgusted by that ultimate imperative of biology: sex. His work is so laden with Freudian imagery that it’s the veritable mother lode for any believer in displacement theory: “rigid” pillars; yawning abysses coated with slimy moisture; dilating doorways leading into dark, strong-smelling tunnels; thick round “Cyclopean” columns (did someone say something about a one-eyed trouser snake?). Read in the right spirit, passages like this one from “The Call of Cthulhu” become hilarious:

…everyone watched the queer recession of the monstrously carven portal. In this phantasy of prismatic distortion it moved anomalously in a diagonal way, so that all the rules of matter and perspective seemed upset.

The aperture was black with a darkness almost material. That tenebrousness was indeed a positive quality; for it obscured such parts of the inner walls as ought to have been revealed, and actually burst forth like smoke from its aeon-long imprisonment, visibly darkening the sun as it slunk away into the shrunken and gibbous sky on flapping membraneous wings. The odour arising from the newly opened depths was intolerable, and at length the quick-eared Hawkins thought he heard a nasty, slopping sound down there.

What makes all of this still more hilarious is that Lovecraft has no idea that he’s doing it. It’s almost enough all by itself to make one a believer in Freud — if one can stop laughing long enough.

And that in turn gets us to the real dirty little secret about Lovecraft, the reason so many of us continue to love this pretentious bigot like we do the racist but entertaining old uncle we see every Thanksgiving: he’s just so fun. He’s the best camp this side of Plan 9 From Outer Space. This is the real reason that people want to take Cthulhu to bed with them as a plush toy. In the countless works of Lovecraftian fiction that have been written by people other than H.P. Lovecraft, the line between parody and homage is always blurred, largely because he’s uniquely impervious to the typical mode of literary parody, that of exaggerating an author’s stylistic tics until they become ridiculous. The problem is that Lovecraft already parodies himself. Really, how could anyone write anything more ostentatiously overwrought than this?

The tramping drew nearer—heaven save me from the sound of those feet and paws and hooves and pads and talons as it commenced to acquire detail! Down limitless reaches of sunless pavement a spark of light flickered in the malodorous wind, and I drew behind the enormous circumference of a Cyclopic column that I might escape for a while the horror that was stalking million-footed toward me through gigantic hypostyles of inhuman dread and phobic antiquity. The flickers increased, and the tramping and dissonant rhythm grew sickeningly loud. In the quivering orange light there stood faintly forth a scene of such stony awe that I gasped from a sheer wonder that conquered even fear and repulsion. Bases of columns whose middles were higher than human sight . . . mere bases of things that must each dwarf the Eiffel Tower to insignificance . . . hieroglyphics carved by unthinkable hands in caverns where daylight can be only a remote legend. . . .

I would not look at the marching things. That I desperately resolved as I heard their creaking joints and nitrous wheezing above the dead music and the dead tramping. It was merciful that they did not speak . . . but God! their crazy torches began to cast shadows on the surface of those stupendous columns. Heaven take it away! Hippopotami should not have human hands and carry torches . . . men should not have the heads of crocodiles. . . .

To those last lines I can only reply… no shit, Sherlock. Long after the cosmic horror has had its moment and you’ve realized that obscure diction doesn’t a great writer make, the camp will always remain. While it may be borderline impossible to parody Lovecraft, it’s great fun for a writer to just go wild once in a while in his unhinged style, to ejaculate purple prose all over the page in an orgasm of terrible writing. (Having once written a Lovecraftian interactive fiction, I fancy I know of what I speak.) This, again, is extremely important to understand when reckoning with his tremendous ongoing popularity, and with the fact that so many excellent writers who really ought to know better — people like Neil Gaiman, China Miéville, Jorge Luis Borges, and Joyce Carol Oates — can’t resist him.

If you haven’t yet read Lovecraft, I certainly recommend that you do so. Love him or hate him, he’s a significant writer with whom everyone — especially, as we’ll begin to see in my next article, those interested in ludic culture — should be at least a little bit familiar. And getting a handle on him isn’t a terribly time-consuming task. While his other works can certainly be rewarding to cosmic-horror aficionados and lovers of camp alike, you can come to understand much or most of what he does and how he does it merely by reading “The Rats in the Walls” and “The Call of Cthulhu.” In my opinion the best of his later works is At the Mountains of Madness, more a work of pulpy Antarctic adventure than horror and all the better for it; his prose here is a bit less purple than his norm. (That said, it does also contains one of the best instances of high Lovecraftian camp ever, when he shows himself perhaps the only person on the planet who can find penguins “grotesque.”) After you’ve read those three all of his writerly cards are pretty much on the table. His other works more amplify his modest collection of themes and approaches than extend them.

Next time we’ll take up another weird tale: how a young game designer turned these nihilistic stories whose protagonists always end up dead or insane into a game that would actually be fun — one that you might even be able to win once in a while.

(The definitive biography of H.P. Lovecraft is and will likely remain S.T. Joshi’s sprawling two-volume I Am Providence. A shorter and more accessible biography is Paul Roland’s The Curious Case of H.P. Lovecraft. Worthwhile online articles can be found at The Atlantic, Salon, The New York Review of Books, and Teeming Brain. The Arkham Archivist has put together The Complete Works of H.P. Lovecraft, a free-to-download ebook for Kindle and EPub readers. Finally, there’s BBC Radio’s excellent Weird Tales: The Strange Life of H.P. Lovecraft.)

Victor Gijsbers

September 18, 2015 at 1:51 pm

O man. Once in a while I wonder whether I should give Lovecraft another god, and then I see a phrase like “gigantic hypostyles of inhuman dread and phobic antiquity” and I think: no. It’s not just that the prose is purple; it’s also just plainly incorrect. “Hypostyle” isn’t a noun, and “phobic” doesn’t mean what Lovecraft thinks it does. Aaargh!

Anyway, I did read the three stories you recommend, so I’ll assume that I already got everything out of Lovecraft that I’ll ever get out of him. ;-)

One typo: “in turned” -> “in turn”

Victor Gijsbers

September 18, 2015 at 1:52 pm

I actually wonder whether I should give him “another go”, not “another god”, but I guess that’s one for Freudian catalog.

Rowan Lipkovits

September 18, 2015 at 4:08 pm

Between the Great Old Ones and the Elder Gods, the one thing the Lovecraft Mythos distinctly does not need is yet another god.

Jimmy Maher

September 18, 2015 at 2:17 pm

Apologists will tell you that Lovecraft was concerned as much with the *sound* of words as their meaning. But…yeah. Joyce he’s not.

Thanks for the correction!

Jason Dyer

September 18, 2015 at 3:35 pm

Hypostyle is allowed to be a noun. (I just checked two different dictionaries.)

What does Lovecraft think phobic means? It’s certainly an odd, uncomfortable use of the word, but not exactly incorrect either; I would say that’s the point.

(I do think there are some terrible bits of prose you can pick out, just this particular excerpt seems fine to me.)

Victor Gijsbers

September 19, 2015 at 8:49 am

It’s not a noun according to Mirriam-Webster, the Collaborative International Dictionary of English, and VanDale. But apparently other dictionaries have other opinions.

Lovecraft seems to think that “phobic” means “fearsome” — “phobic antiquity” presumably means “so old that its very oldness is fearsome”. But “phobic” means “plagued by fears,” and that just makes no sense here.

hüth

September 19, 2015 at 8:43 pm

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/hypostyle

Oxford, of course, being the one that Lovecraft would’ve cared about.

luxhibernia

October 11, 2015 at 3:17 pm

‘Phobic’ can also mean ‘of Phobos’ if you’re writing in the cosmic horror vein.

Many modern readers do not have the ear for romantic, gothic or mannerist prose because they have learned that less is more and that a writer must say exactly what they want to convey.

That’s not what Lovecraft is trying to do.

Andrew Plotkin

September 18, 2015 at 2:38 pm

Whenever Lovecraft is discussed, I like to bring up my pet theory, which is that he attained immortality *because* he was such a terrible stylist. “Damn,” every writer thinks, “what if I could tap that vein of cosmic nihilism and existential terror *and also not suck?*” And thus the Lovecraftian exocanon grows.

(Like Lovecraft’s writing itself, this theory is not entirely convincing, but you have to admit it’s part of it.)

I’m going to be completely tedious and insist that True Detective does not contain references to Lovecraft, but to Robert W. Chambers, of the *previous* generation of American weird-tales writing. Lovecraft’s use of “Carcosa” and “Hastur” were his bid to keep *Chambers* current (along with his contemporary Ambrose Bierce, I see). True Detective continues that tradition.

If you want a 2014 example, try “The Litany of Earth”, a short story by Ruthanna Emrys. (http://www.tor.com/2014/05/14/the-litany-of-earth-ruthanna-emrys/). Recommended.

(Typo: “eldrich” should be “eldritch”. A word I first learned from _Wishbringer_, as it happens.) (And _Spellbreaker_ has some Cyclopean ruins, surely a passing bit of homage.)

Jimmy Maher

September 18, 2015 at 5:10 pm

It’s a fine theory, I’d say. What does certainly seem clear is that Lovecraft in the original has always been more popular with *writers* than *readers*. It’s largely because of their eagerness to take up his mantle that the Mythos has endured. Lots of them take the mythology of the Mythos far more seriously than Lovecraft ever did.

The Mythos is also just about the newest storyworld that is largely free of copyright concerns, which has also allowed it to thrive in a way that many more recent properties can’t. I think I’ll be getting at least a bit more into that in my next article.

Leaving aside the rather disappointing big reveals in the last episode or two of True Detective, much of the nihilist philosophy spouted by… what’s his name, Matthew McConaughey’s character, did feel very Lovecraftian to me. And of course the entire show is very much an homage to the pulps, something most critics forgot until those last episodes made it very plain indeed. But I won’t quibble too much about a topic I have a feeling you know more about than I do. ;)

I’d missed or forgotten those bits of Wishbringer and Spellbreaker. It’s of course notable that the latter was written by Dave Lebling, later the author of The Lurking Horror and so obviously at least something of a Lovecraft fan. Perhaps also relevant: Lebling was often teased by the other Imps for the tendency of his prose to get a bit purpleish, but most of that was excised by the time his games hit the shelves, thanks to Infocom’s editorial process and, probably most of all, to the harsh space limitations of the Z-Machine. Would that Lovecraft had labored under similar restrictions…

And thanks for the correction and the recommendation. I’ll look it up!

matt w

September 19, 2015 at 4:08 am

“much of the nihilist philosophy spouted by… what’s his name, Matthew McConaughey’s character, did feel very Lovecraftian to me”

I’ve read that it was specifically influenced by Thomas Ligotti.

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 8:25 am

Ligotti is a noted fan of Lovecraft, so there is that. A quote:

“Poe and Lovecraft – not to mention Bruno Schulz or Franz Kafka – were what the world at large would consider extremely disturbed individuals. And most people who are that disturbed are not able to create works of fiction. These are people who are just on the cusp of total psychological derangement. Sometimes they cross over and fall into the province of ‘outsider artists.’ That’s where the future development of horror fiction lies – in the next person who is almost too emotionally and psychologically damaged to live in the world but not too damaged to produce fiction.”

Felix

September 18, 2015 at 3:35 pm

From Lovecraft’s work I’ve only read The Color Out of Space, and while the climax is amazing, with the party coming at the farm to find the dying family, I had to skim over most of the text to get there at all. And that was a Romanian translation, presumably better written than the original (as it would be difficult to do worse). At least the story features a well-designed monster for a change; nowadays, Cthulhu and shoggots are more commonly the stuff of parodies — the former at the very least is likelier to be depicted as a cute plushie or funny cartoon than anything resembling the spirit of the original. And for good reason: the world is largely composed of grown-ups, while Lovecraft, as you pointed out, stopped short of that stage in his life. To be honest, I find it remarkable that people can still write straight-up horror based on his ideas, let alone as masterfully as you did; after all, Lovecraft was ultimately little more than a child afraid of the dark. But then again, I suppose such primal fears remain buried deep in all of us, from where the right words can awaken them again and bring them to the surface, to spill over the facade of self-assurance we’ve built over the years.

Lovecraft was terrified by the universe’s mind-boggling scale, but all too often we find ourselves tiny and insignificant even compared to the world immediately around us. And that, ironically, makes him a visionary in retrospect.

Jimmy Maher

September 18, 2015 at 5:17 pm

That’s actually interesting to think about. Just how would one go about *translating* Lovecraft? Trying to capture all of those anachronistic spellings and obsolete words and then trying to misuse so many of them and to tangle the grammar all to hell. The mind boggles. I’d probably just say, “Screw it!” and write the same story in my own vernacular — which, as you said, could hardly read much worse. Maybe there are a bunch of Germans or Frenchmen or Russians wandering around going, “You know, I don’t know why everyone complains, this Lovecraft fellow’s writing’s really not half bad.”

Duncan Stevens

September 19, 2015 at 3:51 am

Somewhere in a box in my basement I have a book of Lovecraft stories, translated into French. I got through some of them, long ago, but I don’t remember what the translator did with his wacky diction.

At some point soon I’ll get those books out of those boxes onto shelves (need to get shelves installed)–when I do, I’ll set that book aside and take another look. If the results are amusing, I’ll send Jimmy some excerpts.

Poddy

September 19, 2015 at 5:08 pm

http://www.noosfere.com/icarus/livres/niourf.asp?numlivre=2146580806

I distinctly remember this translator used ‘innommable’ a lot. Possibly every fourth word, in fact.

Poddy

September 18, 2015 at 3:48 pm

I have always felt strongly that Lovecraft’s forte wasn’t horror, but fantasy, particularly Dunsanian pastiche. I discovered him in high school for his horror, same as anyone, but the only things of his I ever go back to are texts like “Celephais”, or “The Quest of Iranon”, or “The Cats of Ulthar”, or even “The Doom That Came to Sarnath”. “Celephais” is particularly interesting in what it reveals of Lovecraft’s self-perception.

As for “True Detective”, yeah, I don’t even think it did a good job of Chambers.

TsuDhoNimh

September 18, 2015 at 4:10 pm

Because I can’t resist:

” I believe that our collective psyche sill struggles with the ramifications of that realization today”: typo: sill should be still.

I think you did a great job in this post capturing the spirit of what makes Lovecraft simultaneously so good and so bad (or is it so bad it’s good?).

Jimmy Maher

September 18, 2015 at 5:22 pm

Thanks!

Some readers do occasionally get irate about the typo corrections, apparently seeing it as disrespectfully focusing on trivialities. I know their hearts are in the right place when they do so, so in a perverse way I appreciate it. But I *also* hugely appreciate the corrections. I take my writing seriously and want it to be correct. So, no need to resist!

LAK

September 18, 2015 at 9:34 pm

Nice writing, as always!

“heredity evil and madness”: should this be “hereditary evil and madness”, or maybe “heredity, evil, and madness”? Either is certainly appropriate for HPL…

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 8:17 am

The former. If I start writing of “legendry” or things I was “shewn,” someone please give me a good shake. Thanks!

DZ-Jay

March 23, 2017 at 11:22 am

I’m one of those who submits the occasional correction (well, OK, more than occasional). I do so for two primary reasons, and without any intent to appear superior, to condescend, or to belittle the author’s efforts.

The first reason is a matter of literary effect. I enjoy reading, and as others with the same affinity to the written word, reading evokes a personal connection between the mind of the author and mine in a deeply personal way. Thus, I immerse myself in the text, almost trance-like, following the narrative and furthering the connection to a tight bond with the author when his ideas take form as mine and — whether accepted or agreed upon, or not — at least are assimilated enough to be considered, though briefly, at a personal level.

It should then be understandable that a typo, a grammatical error, a sharp variance in style, or even a stilted or awkward clause construction can jar me abruptly from this trance — in much the same way that an incongruous element of scenery or dialog in a movie breaks irrevocably the suspension of disbelief. We can call this a break in the narrative immersion, and just like its film counterpart, it is distracting, disturbing, and steals away the enjoyment inherent in reading.

Thus, when I offer a correction or a suggestion to improve a sentence or a word, I do it at once to bring myself back into the fold, and to help the author avoid this for future readers (even more when that future reader may be myself at some later time).

The second reason is one of lesser importance: depending on the case to educate, correct the record, help polish the material, or otherwise assist the author in improving his craft in the same way that I wish others would assist me to better my own.

There is one third reason that perhaps applies more to this blog than to most others: the author’s claim to want to publish (and my own personal desire to see) this series in book form. From the beginning this motivated me to be especially critical of diction to ensure the material be well polished for its eventual literary debut. This is because, while in blog format we can always contribute and add comments to correct or enhance the stories; once published there is no such recourse, and such finality of the work demands a thorough screening prior to its publication.

What I hope comes from the above, and indeed what I deeply hope the author takes away from my own personal comments on his work, is that it is done out of a sincere admiration to the author’s work itself. That the articles are so interesting, so fascinating, and I enjoy them so much, that I wish to polish them to perfection not only for others to enjoy, but for myself to re-read in years to come and rekindle that enjoyment.

And if sometimes I fail to praise a particular piece is not for lack of interest or dislike, but because it sometimes feels that the work is so good on its own merits, that this should appear obvious to everyone, when in fact it may be only so inside my head.

Keep up the good work! (And sorry for the constant corrections, I hope they help.)

Sincerely,

-dZ.

Duncan Stevens

September 18, 2015 at 4:35 pm

The question has occasionally been kicked around on the IF newsgroups: why do IF authors come back to Lovecraft so often (when writing horror games–i.e., why not other subgenres of horror)? I think there are a few reasons:

1. Lovecraftian horror lends itself well to puzzle-solving, i.e., “figure out what’s going on.” (That the answer is always some minor variant of “an evil cult is acting in service of some monstrous alien being” doesn’t seem to be a problem.) Other forms of horror that primarily involve running away from some menace don’t work as well in that respect.

Letting the story revolve around a mystery helps solve the pacing problems that otherwise tend to afflict IF. It’s not necessarily a problem if the player stops to inspect the scenery for 200 turns while investigating mysterious disappearances, but if the main source of dramatic tension is a guy chasing you with an axe, it’s probably not a good thing if everything pauses while the player searches some flowerbeds.

Lovecraftian plots lend themselves particularly well to mystery-style plots because the answer is always big and dramatic: it’s a plot that will *destroy the world* (or maybe just the town?). It makes for a more exciting resolution than “the murderer is Joe.”

2. Lovecraftian horror makes for writerly, uh, flourishes. Or encourages bad writerly behavior, depending on how you look at it. There’s more room for imagination in depicting how unedifying the monster and its minions are than in describing how mean the murderer looks or how sharp his axe is. That leads, of course, to all sorts of excesses, as you note. (There’s one semi-amusing moment in Michael Gentry’s Anchorhead where the game essentially says “It was so horrible than I just can’t describe it.” Haven’t read enough Lovecraft to know whether that’s an homage to something Lovecraft liked to do.)

3. IF authors have, by and large, read a lot of the same stuff, and even if they haven’t read Lovecraft, they’ve read folks heavily influenced by him. Their horror writing tends inevitably to gravitate back to his model. Boring, but probably true.

Jimmy Maher

September 18, 2015 at 5:29 pm

I’ll be getting into your first point in particular in the next article. Many Lovecraft stories are structured as mysteries, which work really, really well as games — the story has already been written, you’re just trying to uncover how it played out. This avoids many of the more intractable problems normally associated with interactive storytelling.

I would add a possible fourth reason:

Most other forms of horror tend to have a religious dimension involving damned souls, etc. But religion, at least in the games themselves, has never been particularly popular with the IF community. Lovecraft removes the horror from that traditionalist paradigm to one more abstract and science-fictional. I think this feels more in keeping with the community’s sensibilities.

Oh, and if I ever draw up a Lovecraft drinking game I’m definitely going to include “Drink once every time Lovecraft calls something ‘indescribable’ and then proceeds to describe it at feverish length.”

Duncan Stevens

September 18, 2015 at 7:19 pm

Oh, and if I ever draw up a Lovecraft drinking game I’m definitely going to include “Drink once every time Lovecraft calls something ‘indescribable’ and then proceeds to describe it at feverish length.”

Maybe the implication is “can’t be described in a coherent way, so here’s the incoherent version.”

Christina Nordlander

September 18, 2015 at 9:31 pm

I have to admit, your fourth reason doesn’t seem very compelling to me. A lot of horror subgenres (such as slasher and other non-supernatural horrors) don’t have a religious dimension. Ghosts and vampires do of course have their origins in religious concepts (leaving zombies out of this for now, since I 1) know very little of Voodoo, and 2) realise that the modern popculture zombie is very different from the original belief), but in modern fiction about such creatures, those themes are so obscured as to be invisible unless the author goes out of their way to emphasise them.

I agree that Lovecraft was the originator, or at least a major force, of horror fiction that is largely unconnected to religious or moral themes, but in the 21st century, that’s not something unique to cosmic horror specifically.

Loving your blog, by the way. Keep it up!

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 7:48 am

Yeah, I could have been more coherent. But if we limit ourselves to *supernatural* horror I think there’s something to be said for it. I think the more recent fondness for zombies in IF may spring from much the same place. And of course all of this is by no means limited to the IF community, but probably also applies to the broader culture’s love for Lovecraft and zombies these days.

Dave

September 18, 2015 at 6:16 pm

Duncan Stevens: >> (There’s one semi-amusing moment in Michael Gentry’s Anchorhead where the game essentially says “It was so horrible than I just can’t describe it.” Haven’t read enough Lovecraft to know whether that’s an homage to something Lovecraft liked to do.)

It is. The (very) short story “The Unnamable” is the classic case, and quite a mix of self-awareness and irony:

“Besides, he added, my constant talk about ‘unnamable’ and ‘unmentionable’ things was a very puerile device, quite in keeping with my lowly standing as an author. I was too fond of ending my stories with sights or sounds which paralyzed my heroes’ faculties and left them without courage, words, or associations to tell what they had experienced.”

Back to the larger topic, I’d recommend The Silver Key story, almost an autobiography of fantastic errors:

“He had read much of things as they are, and talked with too many people. Well-meaning philosophers had taught him to look into the logical relations of things, and analyse the processes which shaped his thoughts and fancies. Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other. Custom had dinned into his ears a superstitious reverence for that which tangibly and physically exists, and had made him secretly ashamed to dwell in visions. Wise men told him his simple fancies were inane and childish, and even more absurd because their actors persist in fancying them full of meaning and purpose as the blind cosmos grinds aimlessly on from nothing to something and from something back to nothing again, neither heeding nor knowing the wishes or existence of the minds that flicker for a second now and then in the darkness. ”

And Jimmy, the King of Shreds and Patches remains the only IF game I have finished to date, and what got me interested in your blog in the first place… Keep writing!

Baf

September 18, 2015 at 7:44 pm

Calling things “indescribable” is very much something Lovecraft liked to do.

MrEntropy

September 18, 2015 at 5:48 pm

My favorite Lovecraft tale is “The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath”

Matthew W

September 18, 2015 at 8:50 pm

I don’t think Lovecraft is as bad a writer as he’s made out to be. I think he is a massively uneven writer, While lots of his sentences are terrible, some are pretty good, maybe even very good – the introduction to Call of Cthulhu that you quote for example.

(I think Tolkien’s unevenness also leads to underestimation of his – far superior – technical abilities).

For me one of the big attractions of Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos is its sheer alienness. At their best his creations really are jarringly different and starnge.

Matthew W

September 18, 2015 at 8:52 pm

ps Great article, great blog!

Joachim

September 18, 2015 at 9:11 pm

I recently read The Horror of Red Hook and, like you, I thought the place was fictional. But apparently not: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Hook,_Brooklyn

Joachim

September 18, 2015 at 9:23 pm

By the way, that was one of the Lovecraft-stories I found most disturbing. Mostly because I read it right around the time of the horrifying massacre of the yezidis in Iraq, and here this story was referring to that whole ethnic group as devil worshippers. Just felt very wrong.

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 7:45 am

Yeah, this is what makes the “just a man of his time” defense so hopeless when applied to Lovecraft’s racism: his racism is not incidental but fundamental to his stories. If you remove it you remove much of what he himself was consciously trying to say.

hüth

September 19, 2015 at 8:52 pm

He’s also, very specifically, *not* a man of his time.

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 7:40 am

Woops! Thanks, fixed.

Keith Palmer

September 18, 2015 at 10:20 pm

Knowing the narrative here would be getting to The Lurking Horror soon, I was wondering about bringing up how, while that game could be called “Lovecraftian,” works of interactive fiction from the following decade would push the resemblance much closer… Getting a full “prologue” like this one was an interesting surprise.

In any case, I’d heard a fair bit about “the importance of Lovecraft” by the time I found some S.T. Joshi-edited collections in a library just out of university (and, not that long afterwards, Penguin Books put out some collections, also with slightly prim introductions by Joshi…) I acknowledge how he tapped into “the terror of cosmic scale,” but seem better able at compartmentalizing the intimidation it packs in his stories, perhaps by taking in the more optimistic side of science fiction (although aware the “Lovecraftian” rebuttal would involve mentioning something about “denial”…) Perhaps I have a soft spot for the Lovecraft story “The Shunned House,” in which the evil force is a bit less overwhelming, and find some food for thought in at least some of the non-human beings of “At the Mountains of Madness” and “The Shadow Out Of Time” starting to seem less “incomprehensible” (As a small note of correction, though, I noticed you referring to “John W. Campbell’s Astounding”; he didn’t become editor of that magazine until the summer of 1937, just after Lovecraft’s death.)

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 8:20 am

There is a shift that happens after “The Call of Cthluhu,” the evils in Lovecraft’s stories going from being unexplained supernatural entities to alien visitors. That’s doubtless what you remarked.

And… correction made. Thanks!

Petter Sjölund

September 19, 2015 at 1:15 am

I suppose it should be mentioned that Red Hook is a real district i Brooklyn.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Hook,_Brooklyn

Petter Sjölund

September 19, 2015 at 4:02 pm

(Written when the other, nearly identical comment above was still in moderation. Feel free to delete this.)

S. John Ross

September 19, 2015 at 6:47 am

This is my favorite piece on HPL ever. Thank you.

S. John Ross

September 19, 2015 at 7:02 am

(A little surprised to see no mention of Dunsany, though!)

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 8:28 am

Yeah, that was one of the things that I elected not to go into in order to keep the article manageable. I usually try to keep these articles to no more than about 7000 words (although I don’t *always* succeed), and I wasn’t eager to split this one into a two-parter.

Janice M. Eisen

September 19, 2015 at 7:55 am

I’ve often been embarrassed to admit that I find Lovecraft utterly unreadable, but after reading this, I feel better about it. I appreciated the look at his life, as well as the reasons for his outsize influence on the genre in both textual and ludic forms.

Since you request corrections, I must second Keith Palmer’s comment about Campbell not being editor of Astounding at the time; also, the magazine was still named Astounding Stories then, as you can see on the cover you reproduce.

There’s a lot of controversy in the fantasy/horror community right now over whether the World Fantasy Award, which is a bust that’s a caricature of Lovecraft designed by Gahan Wilson, should change its design. Some writers of color who have won the award are very much in favor of changing it, while Lovecraft partisans like Joshi insist that you can separate the man’s literary contributions from the less savory parts of his personality. I tend to think they should change it, especially if it is disturbing actual winners of the award, and having seen some of the worst racist stuff HPL wrote.

Arkadiusz Dymek

September 19, 2015 at 10:02 am

A sidenote on Lovecraft mainstreaming:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cthulhu_Regio

Bernie

September 19, 2015 at 1:13 pm

Aren’t we being a little too hard on Lovecraft ? Yes, he made up words and wasn,nt careful with his grammar. But, as your article shows, he never denied being an amateur and a non-professional. He was pretentious about being “old money” but was honest and humble about not being “a writer”.

And furthermore : I’m a fan of his stories not because of his artistic sensibilities. I read Shakespeare and Conrad when I want that. For me, Lovecraft is about settings, environments : the old, inbred, in-grown towns, the wretched country folk, the derelict mansions, the “mongrel” and “evil” peoples, ancient books : perhaps you should focus less on Cthulu and the Cyclopean and more on Arkham, Miskatonic University. You should have mentioned the “mad arab Abdul Alhazred” and his “Necronomicon”. In my opinion, it’s those details that draw us to Lovecraft, not his “arguments” and “logic”. No one can deny that’s indeed the case with his most conspicuous artistic heir Stepehen King. If you can think of Lovecraft as a professional writer without his trademark quirks, a commercial writer, King is what comes to mind. So, if you want know why we like Lovecraft, ask yourselves what made Stephen King a millionaire : what Lovecraft did as a hobby, King turned into a science.

Jimmy Maher

September 20, 2015 at 7:24 am

You of course absolutely should make up your own mind about Lovecraft, as with everything I write about — that’s why I always try to point out where you can find stuff yourself to play or, in this case, read — but I do fear there are a couple of misunderstandings creeping in here.

The first and most significant is this idea of Lovecraft as an “amateur” writer. While I do think there’s a great thesis to be written on him as an “outsider” artist, like Daniel Johnston (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Johnston) and Henry Darger (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Darger), Lovecraft himself would not have equated his “amateur” status with lack of ability or seriousness of intent or literary merit. Just the opposite, in fact. He adopted (or affected) the values of a member of the 18th-century landed gentry. An important part of these was the idea that commercial work was demeaning for a gentleman of quality like (he saw) himself, and demeaning for the literary work itself as well. It’s one of those constant ironies that mark his life, sometimes funny and sometimes kind of pathetic and often both, that he was publishing this work that aspired to echo Pope and Swift and Johnson and of course Poe in the pulps, just about the least respectable literary organs out there. And Weird Tales wasn’t even a particularly good or popular pulp at that! Read that initial submission letter and think about how strange it must have read to the people who received it. It seems safe to say that nobody had ever written them a letter like that before — and never would again, save for more correspondence from good old Howard.

The other thing I’d like to point out is that I don’t consider King a particularly Lovecraftian writer, and I don’t think many others do either. His relationship with Lovecraft has been complicated. He’s mentioned how fascinating he found him on first reading him as a boy and provided glowing blurbs for Lovecraft story collections, but he’s also dismissed him from time to time as essentially an adolescent’s idea of horror. King’s horror tends to be grounded in psychology and personality, something Lovecraft with his famously flat and homogenous characters never even attempted. Even when he’s writing a deliberate homage, as he did recently, I don’t think he gets all that close to the feel of the original.

Other writers do, of course, and often combine it with a much more accessible and elegant style of, you know, writing. Certainly no one could argue against Lovecraft’s influence.

Anyway, just some food for thought. Thanks for commenting, and feel free to continue to enjoy Lovecraft. ;)

Cmdrfan

October 3, 2015 at 7:11 pm

I really have to thank you for the generous enlightment you give us, your readers, with each article and each response to the comments. I really appreciate it.

All these posts about Lovecraft’s work make me think that perhaps you should publish something on William Gibson, starting with his “Gernsback Continuum”. Although it isn’t a horror / fantasy story, I find it’s “anti-Camp” argument very relevant to our little debate here. And , what better example of “unconventional ” style than Gibson ?.

Thanks Again for a great blog !

Jimmy Maher

October 4, 2015 at 9:10 am

You’re welcome! I do plan to write at some length on William Gibson before covering Interplay’s Neuromancer game. I absolutely love “The Gernsback Continuum,” maybe more than he anything else he ever wrote. Thanks for reminding me to talk about it!

Brian Bagnall

September 19, 2015 at 4:38 pm

Thanks for giving Lovecraft a complete article in preparation for Lurking Horror. One of the best gaming experiences I’ve ever had was Alone in the Dark, which is unabashedly lovecraftian. Not only the first real survival horror game (some say Project Firestart was), but it had the perfect music to set the tone. That game introduced me to this Lovecraft person, and to be honest, his stories were somewhat of a disappointment after such a stellar game.

Another great gaming experience was Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth. This fairly humble game had such mystery and a great progression as things become gradually weirder and weirder. The slightly off townsfolk were quite memorable in that one, and led me to read its inspiration, The Shadow Over Innsmouth.

I guess people might also say Doom was a Lovecraft inspired game in many ways. Even with his fertile imagination, Lovecraft never could have predicted his books would inspire works in a media that didn’t even exist during his time.

As for his xenophobia, you can also add penguinphobia.

Typo: “finally awakening”

BTW Is it me, or does the cover of Astounding Stories resemble a couple of Ghostbusters running away from Slimer?

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2015 at 4:49 pm

Some levels of Doom were designed by Sandy Petersen, who also designed the Call of Cthulhu tabletop RPG. So, yes, definitely a big influence there as in so many other places.

And thanks for the correction!

Brian Bagnall

October 23, 2015 at 6:45 pm

By the way, At the Mountains of Madness uses the phrase “lurking horror” a few times, so perhaps that’s what inspired the title of Dave Lebling’s game.

Martin

August 23, 2016 at 2:50 am

More likely, a fragment that Lovecraft wrote that August Derleth wrote a story around – “The Lurker at the Threshold”.

Martin

August 23, 2016 at 2:54 am

Or “The Lurking Fear”, of course.

Pedro Timóteo

September 19, 2015 at 6:26 pm

Like a few others, I’m more generous to Lovecraft than you seem to be in your post (which I loved, don’t get me wrong). I see the faults in his writing, but to me they’re really part of the charm; without the purple prose, his stories wouldn’t be half the fun (or half the length, for that matter).

I actually prefer The Shadow over Innsmouth to The Call of Cthulhu. While the former’s only sin (other than the racism / fear of “race mixing” common to Lovecraft) is that it ends a bit too abruptly (but until then it has a fantastic atmosphere, more creepy than scary), I think Cthulhu, while still a great pulp story, suffers from the presence of a cult that kills people who find out too much about it. If the story had ended with the narrator afraid of Cthulhu’s eventual awakening, and doubting his sanity, I think it would have worked out better than “I probably won’t last long, the cult knows I know too much”. This is just my personal taste, though.

Also, I’m currently playing through your KoSaP game, and it’s been great so far, though I’m still near the beginning (too little free time, mostly — the game isn’t particularly hard, especially with the think command). It came as a surprise, when reading this post, that you don’t seem to actually like Lovecraft that much. :)

Dave G.

September 21, 2015 at 4:57 am

“The Shadow over Innsmouth” borrows a lot from the hard core detective potboilers of its day. Lovecraft must have been influenced by his contemporaries who specialized in that genre. And because of that it’s a real page turner, unusual for Lovecraft.

Lisa H.

September 20, 2015 at 4:58 am

There’s lots of words that you’ll only find in Lovecraft, to such an extent that you know as soon as you see one of them that you’re reading either him or one of his imitators: “eldritch,” “Cyclopean,” “daemonic.”

None of these are only found in Lovecraft, uncommon though they may be. “Eldritch” dates to the early 1500s (besides the use in Wishbringer that someone else noted, and also the same “eldritch vapor” appears in in Beyond Zork); “Cyclopean” to the mid-1600s (although maybe not in the sense something like “amazingly huge” that Lovecraft seems to use it; it’s hard to tell just from the quick dictionary check I made); “daemonic” may be an affected spelling, but relates to Latin daemon or Greek daimon.

he would invariably seek out the oldest section of any place he visited and explore it at exhaustive length, preferably by moonlight.

This sounds a bit like urban exploration aka building hacking or tunnel hacking, to me, which, now that I say it, seems similar to certain parts of The Lurking Horror.

he’s uniquely impervious to the typical mode of literary parity

…parody, I assume you mean? (although perhaps one cannot have literary parity with him either!)

the horror that was stalking million-footed toward me through gigantic hypostyles of inhuman dread

FWIW I seem to remember using “hypostyle” as a noun in art history class, although it might have been just a shorthand for terms like “hypostyle hall” and not exactly a noun in the proper sense.

Jimmy Maher

September 20, 2015 at 7:35 am

Okay, when you find them in relatively *modern* works you know it’s Lovecraft or Lovecraftian. ;) I think the instances in Infocom are almost certainly deliberate homages.

Thanks for the correction!

Lisa H.

September 20, 2015 at 8:05 pm

I didn’t mean that the words were necessarily archaic simply because they have older origins, although they may sound a bit pretentious, rather that they were not Lovecraft’s inventions. I don’t think I’ve encountered “Cyclopean” much but I have definitely read “eldritch” and “daemonic” in modern works both fiction and non-fiction that are not Lovecraftian in nature.

Doug Orleans

September 21, 2015 at 3:58 am

In particular, Victor Frankenstein often calls his creation a daemon, in Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel.

Peter Piers

February 15, 2016 at 5:39 pm

FWIW, “eldtrich” appears somewhat frequently in Terry Pratchett – but it’s a running gag that no one really knows what it means, including the people who use the word. It was used in The Light Fantastic to describe the Luggage, by, I think, Cohen the Barbarian; since then, people tend to think eldtrich means wooden or, more often, oblong.

ZUrlocker

September 20, 2015 at 2:25 pm

Love this post. For those who find HP Lovecraft hard to read, you might find the adaptations in radio and graphic novels more accessible.

HPLHS Radio adaptations: