“Writing a book is staring at a piece of paper until your forehead bleeds.”

— Douglas Adams

Shortly after the release of his second Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy novel, with the money now pouring in and showing no signs of stopping, Douglas Adams moved from his dingy little shared flat in Islington’s Highbury New Park to a sprawling place on Upper Street. Later to be described down almost to the last detail as Fenchurch’s flat in So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, the place had one floor that consisted of but a single huge L-shaped room that, coming complete as it did with a bar, was perfect for the grand parties he would soon be holding there.

There was just one problem: he couldn’t get his bank to acknowledge the fact that he had moved. For the rest of his life Adams swore up and down that he had done everything exactly as one was supposed to, had dutifully gone personally down to his local branch of Barclays Bank, filled out a change-of-address form, and handed it to a woman behind the counter. Barclays duly acknowledged the change — and sent said acknowledgement to his old address in Highbury New Park. Adams wrote them back, pointing out the mistake, which the bank promptly and contritely apologized for. Said apology was sent, once again, to Highbury New Park. This cycle continued, as Adams told the story anyway, for no less than two infuriating years. Toward the end of that period, having tried politeness, bluster, threats, and reason, he resorted to charm and outright bribery in a letter to one Miss Wilcox of Barclays, gifting her with a book and even holding out a tempting possibility of marriage to a hugely successful author — namely, him — if she would just change his damn address in her bank’s computers already.

My address is at the top of this letter. It is also at the top of my previous letter to you. I am not trying to hide anything from you. If you write to me at this address I will reply. If you write to me care of my accountant, he will reply, which would be better still. If you write to me at Highbury New Park, the chances are that I won’t reply because your letter will probably not reach me, because I don’t live there any more. I haven’t lived there for two years. I moved. Two years ago. I wrote to you about it, remember?

Dear Miss Wilcox, I am sure you are a very lovely person, and that if I were to meet you I would feel ashamed at having lost my temper with you in this way. I’m sure it’s not your fault personally and that if I had to do your job I would hate it. Let me take you away from all this. Come to London. Let me show you where I live, so that you can see it is indeed in Upper Street. I will even take you to Highbury New Park and introduce you to the man who has been living there for the past two years so that you can see for yourself that it isn’t me. I could take you out to dinner and slip you little change-of-address cards across the table. We could even get married and go and live in a villa in Spain, though how would we get anyone in your department to understand that we had moved? I enclose a copy of my new book which I hope will cheer you up. Happy Christmas.

History does not record whether this passionate missive was the one that finally did the trick.

Most writers collect interesting, humorous, and/or frustrating incidents as they go about their daily lives, jotting them down literally or metaphorically for future use, and Douglas Adams was certainly no exception. He tried to shoehorn this one into Life, the Universe, and Everything, his third Hitchhiker’s novel, via an extended riff about a change-of-address card that fouls up a planet’s central computer systems so badly that they initiate a nuclear Armageddon, but it just didn’t work somehow. The whole sequence ended up getting condensed down to a one-line gag in an extract from the in-book Hitchhiker’s Guide, listing “trying to get the Brantisvogan Civil Service to acknowledge a change-of-address card” as one of life’s great impossibilities. Still, he continued to believe the anecdote was worthy of more than that, worthy of more even than becoming just another of the arsenal of funny stories with which he amused journalists, fans, and party attendees alike.

It seems that it was the process of making the infuriating, subversive, brilliant Hitchhiker’s game with Infocom that first prompted Adams to think about making a game out of his travails with Barclays, along with the insane bureaucratic machinations of modern life in general. It was at any rate during Steve Meretzky’s visit to England to work on the Hitchhiker’s game with him that he first mentioned the idea. Meretzky, busy trying to get this game finished in the face of the immovable force that could be Adams’s talent for procrastination, presumably just nodded politely and tried to get his focus back to the business at hand.

Seven or eight months later, however, with the Hitchhiker’s game finished and selling like crazy, Adams stated definitively to Mike Dornbrook of Infocom that he’d really like to do a social satire of contemporary life called Bureaucracy before turning to the sequel. Asked by Electronic Games magazine at about this time whether he would “soon” be starting on the next Hitchhiker’s game, his answer was blunt: “No. I really feel the need to branch out into fresh areas and clear my head from Hitchhiker’s. I certainly have enjoyed working with Infocom and would very much like to do another adventure game, but on a different topic.”

The desire of this boundlessly original thinker to just be done with Hitchhiker’s, to do something else for God’s sake, certainly isn’t hard to understand. What had begun back in 1978 as a one-off six-episode radio serial, produced on a shoestring for the BBC, had seven years later ballooned into a second radio serial, four novels, a television show, a stage production, a pair of double albums, and now, so everyone assumed, a burgeoning series of computer games. Adams himself had a hand to a lesser or (usually) a greater extent in every single one of these productions, not to mention having spent quite some time drafting and fruitlessly hawking a Hitchhiker’s movie script to Hollywood. It had been all Hitchhiker’s all day every day for seven years.

Being the soul of comedy for millions of young science-fiction nerds had never been an entirely comfortable role for Adams. Sometimes the gulf between him and his most loyal fans could be hard to bridge, could leave him feeling downright estranged. Eugen Beers, his publicist, describes the most obsessive of his fans in terms that bring to mind a certain beloved old Saturday Night Live skit:

One of my abiding memories is how much he loathed book signings. It’s always a scary time for an author when you actually meet your fans, and Douglas had some of the ugliest and certainly some of the most boring people I’ve ever met in the whole of my life. They would come up to him to get their book signed and say, “I notice on page 45 you refer to…” and Douglas would say, “I haven’t got a clue what they’re talking about.”

Beers notes that Adams was “incredibly patient, in fact patient beyond anything I would have been.” Yet, and ungenerous as Beers’s description of the fans may be, the disconnect was real. Adams’s heroes growing up had been The Goon Show and later Monty Python, not Arthur C. Clarke or Robert A. Heinlein. He desperately wanted to prove himself as a humorist of general note, not just that wacky Hitchhiker’s guy that the nerds all like. Yes, Hitchhiker’s had made him rich, had paid for that wonderful Islington flat and all those lavish parties, but at some point enough had to be enough.

Infocom’s great misfortune was to have barely begun their own Hitchhiker’s odyssey just as Adams finally decided to bring his to an end. On the one hand, Adams’s desire to explore new territory must have sounded a sympathetic chord for many of the Imps; they had after all refused to continue the Zork series beyond three games out of a similar desire to not get stereotyped. But on the other hand they all had, and not without good reason, envisioned Hitchhiker’s as a cash cow that would last Infocom for the remainder of the decade, a new guaranteed bestseller appearing like clockwork every Christmas to buoy them over whatever financial trials the rest of the year might have brought. For Mike Dornbrook it must have felt like a nightmare repeating. First he had been deprived far too soon of the Zork series, the first of which still remained Infocom’s best-selling game; now it looked like something similar was happening even more quickly to the would-be Hitchhiker’s series, whose first game had become their second best-selling. In describing why he was “concerned” about making Bureaucracy Infocom’s Douglas Adams game for 1985 and pushing the next Hitchhiker’s game to 1986 at best, Dornbrook unconsciously echoes Adams’s own reasoning for wanting to move on: “The whole financial deal we had signed with him was based on a bestselling line of books that was very, very popular, very well-known. He hadn’t proved himself at anything else yet, for one thing. It was a little hard telling him that…”

It was a little hard to tell him, so Dornbrook and Infocom largely didn’t out of a desire to keep Adams happy. As his current contract with Infocom only covered Hitchhiker’s games, it was necessary to negotiate a new one for Bureaucracy. Dornbrook had some hopes of getting Adams at something of a discount, given that he’d be coming this time without the Hitchhiker’s name attached, but he was stymied even in this by Ed Victor, Adams’s tough negotiator of an agent. Infocom was left saddled with a game that they didn’t really want to do, which they would have to pay Adams for as if it was one that they wanted very badly indeed.

As Dornbrook and other staffers have occasionally noted over the years, there was nothing in Infocom’s Hitchhiker’s contract that technically prevented them from just going off and doing the next Hitchhiker’s game on their own, whether in tandem with or instead of Bureaucracy. The contract simply gave Infocom the right to make up to six Hitchhiker’s games for the cost of a certain percentage of the revenue generated thereby, full stop. They’ve stated that it was their respect for Adams as a writer and as a person that prevented them from ever seriously considering making Hitchhiker’s games without him. I don’t doubt their sincerity in saying this, but it’s also worth noting that to go down that route would be to play with some dangerous fire. While Adams may have been personally sick to death of Hitchhiker’s, he had shown again and again that he considered the franchise to be his and his alone, that if anything got done with it he wanted to do it — or at least to closely oversee it — himself. Not only would a unilateral Infocom Hitchhiker’s game almost certainly spoil their relationship with him for all time, but it risked becoming a public-relations disaster if Adams, never shy of stating his opinions to the press, decided to speak out against it. And could any of the Imps, even Steve Meretzky, really hope to capture Adams’s voice? An Adams-less Hitchhiker’s game risked coming off as a cheap knock-off, as everything that Infocom’s carefully crafted public image said their games weren’t. Thus Bureaucracy — and, for now, Bureaucracy alone — it must be.

In light of its being rather forced upon them in the first place and especially of the exhausting travail that actually making it would become, it’s difficult for most old Infocom staffers to appreciate Bureaucracy‘s intrinsic merits as a concept. Seen in the right light, however, it’s a fairly brilliant idea. Douglas Adams was of course hardly the first to want to satirize the vast, impersonal machines we create in an effort to make modern life manageable, machines that can not only run roughshod over the very individuals they’re meant to serve but that can also trample the often well-meaning people who are sentenced to work within them, even their very creators. What was the Holocaust but a triumph of institutional inertia over the fundamental humanity of the people responsible for its horrors? Years before those horrors Franz Kafka wrote The Trial, the definitive comedy about the banality of bureaucratic evil, a book as funny in its black way as anything Douglas Adams ever wrote. Just to make its black comedy complete, all three of Kafka’s sisters later perished in the Holocaust. Set against those events, Adams’s struggle with Barclays Bank to get his address changed seems like the triviality it truly was.

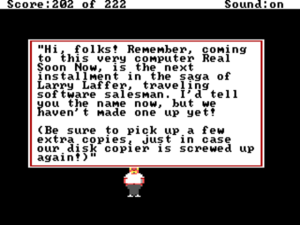

What, though, to make of this idea of a satire of the bureaucratic impulse as interactive fiction? I think there’s a germ of genius in there, a germ of something as brilliant and subversive as anything in the Hitchhiker’s game. Playing a text adventure — yes, even one of Infocom’s — is to often feel like you’re interacting with the world’s pettiest and most remorseless bureaucrat. We’re all only too familiar with sequences like this one, which as it happens is taken from the eventual finished version of Bureaucracy:

>put blank cartridge in computer

[This story isn't allowed to recognise the word "blank."]

[Your blood pressure just went up.]

>i

You're holding an unlabelled cartridge, an address book, a small piece of laminated card, an airline magazine, $57.50, an envelope containing a memo, a power saw, a Swiss army knife, a coupon booklet, a damaged painting of Ronald W. Reagan, a flyer, a Popular Paranoia magazine, your passport, your Boysenberry computer (containing an eclipse predicting cartridge), a small case and a hacksaw. You're wearing a digital wristwatch, and you have a deposit slip and a wallet in your pocket.

>put unlabelled cartridge in computer

You'd have to take out the eclipse predicting cartridge to do that.

>get eclipse cartridge

You're holding too much already.

>drop painting

You drop the damaged painting of Ronald W. Reagan.

You're beginning to feel normal again.

>put unlabelled cartridge in computer

You'd have to take out the eclipse predicting cartridge to do that.

>get eclipse cartridge

You take the eclipse predicting cartridge out of your Boysenberry computer.

>put unlabelled cartridge in computer

The unlabelled cartridge slips into your Boysenberry computer with a thrilling little click...

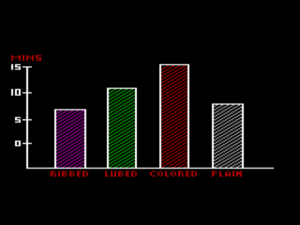

One of Adams’s initial ideas was to have a blood-pressure monitor that would increase every time you got into a tussle with the parser like the one above. This idea made it into the finished game. Yet there are signs, fleeting clues, that that should only have been a beginning, that he would have gone much further, that his idea was to create a game that would end up as, among other things, a self-referential commentary on the medium of interactive fiction itself, a further venturing down the road that the Hitchhiker’s game had already started on with its lying parser and its willingness to integrate your typos into its story. Tim Anderson of Infocom recalls a puzzle involving a pile of boxes, of which you needed to specify one that the parser would obstinately refuse to recognize. How fun such a game could have been is very much up for debate; it sounds likely to run afoul of all of the issues of playability and fairness that make Hitchhiker’s the last game in the world to be emulated by a budding designer of interactive fiction. Nevertheless, I would love to see that original vision of Bureaucracy. While some pieces of it survived into the finished game in the form of the blood-pressure monitor and the snooty, bureaucratic tone of the parser, for the most part it became a different game entirely — or, rather, several different games. Therein lies a tale — and most of the finished game’s problems.

Endeavoring as always to keep Adams happy, Infocom assigned as his partner on the new game no less august an Imp than Marc Blank, who along with Mike Berlyn had been one of the two possible collaborators Adams had specifically requested for the Hitchhiker’s game; he’d had to be convinced to accept Steve Meretzky in their stead. Alas, Blank turned out to be a terrible choice at this particular juncture. He was deeply dissatisfied with the current direction of the company and more interested in telling Al Vezza and the rest of the Board about it at every opportunity than he was in writing more interactive fiction. Bureaucracy thus immediately began to languish in neglect. This precedent would take a long, long time to break. The story at this point gets so surreal that it reads like something out of a Douglas Adams novel — or for that matter a Douglas Adams game. Infocom therefore included it in the finished version of Bureaucracy as an Easter egg entitled “The Strange and Terrible History of Bureaucracy.”

Once upon a time Douglas Adams and Steve Meretzky collaborated on a game called The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Everyone wanted a sequel, but Douglas thought it might be fun to do something different first. He called that something Bureaucracy, and wanted Marc Blank to work on it with him. Of course, Marc was busy, and Douglas was busy, and by the time they could both work on it, they were too busy to work on it. So, Jerry Wolper [a programmer who had collaborated with Mike Berlyn on Cutthroats] got a free trip to Las Vegas to talk to Douglas about it before it was decided to let it rest for a while instead. Jerry decided to go back to school, so Marc and Douglas spent some time on Nantucket looking at llamas, drinking Chateau d'Yquem, and arguing about puzzles. Nothing much happened for a while, except that Marc and Douglas got distracted again. Paul DiLascia [a senior member of the Cornerstone development team] decided to give it a try, but changed his mind and kept working on Cornerstone. Marc went to work for Simon and Schuster, and Paul went to work for Interleaf. Jeff O'Neill finished Ballyhoo, and, casting about for a new project, decided to take it on, about the time Jerry graduated. Jeff got a trip to London out of it. Douglas was enthusiastic, but busy with a movie. Progress was slow, and then Douglas was very busy with something named Dirk Gently. Jeff decided it was time to work on something else, and Brian Moriarty took it over. He visited England, and marvelled at Douglas's CD collection, but progress was slow. Eventually he decided it was time to work on something else. Paul made a cameo appearance, but decided to stay at Interleaf instead. So Chris Reeve and Tim Anderson took it over, and mucked around a lot. Finally, back in Las Vegas, Michael Bywater jumped (or was pushed) in and came to Boston for some serious script-doctoring, which made what was there into what is here. In addition, there were significant contributions from Liz Cyr-Jones, Suzanne Frank, Gary Brennan, Tomas Bok, Max Buxton, Jon Palace, Dave Lebling, Stu Galley, Linde Dynneson, and others too numerous to mention. Most of these people are not dead yet, and apologise for the inconvenience.

Trying to unravel in much more detail this Gordian knot that consumed more than twice as much time as any other Infocom game is fairly hopeless, not least because no one who was around it much wants to talk about it. The project, having been begun to some extent under duress, soon become a veritable albatross, a bad joke for which no one can manage to summon up much of a laugh even today. Jon Palace is typical:

There may be some fun things left in the game, but it left such a bad taste in my mouth. At some point it became, the less I can have to do with it the better. It wasn’t fun doing that game. Bureaucracy is the only game I can remember that was just downright not fun to do.

The natural question, then, is just what went so horribly awry for this game alone among all the others. Infocom’s official version of the tale neglects only to assign the blame where it rightfully belongs: solidly on the doorstep of Douglas Adams.

Adams was a member of a species that’s not as rare as one might expect: the brilliant writer who absolutely hates to write, who finds the process torturous, personally draining to a degree ironically difficult to capture in words. Even during the seven-year heyday of Hitchhiker’s, when he was to all external appearances quite industrious and prolific indeed, he was building a reputation for himself among publishers and agents as one of the most difficult personalities in their line of business, not because he was a jerk or a prima donna like many other authors but simply because he never — never — did the work he said he was going to do when he said he was going to do it. The stories of the lengths people had to go to to get work out of him remain enshrined in publishing legend to this day. Locking him into a small room with a word processor and a single taskmaster/minder and telling him he wasn’t allowed out until he was finished was about the only method that was remotely effective.

It wasn’t as if Infocom had never seen this side of Douglas Adams before. His procrastination had also threatened to scupper the Hitchhiker’s game for a while. They had, however, as they must now have been realizing more and more, gotten very lucky there. With Infocom’s star on the ascendant at that time, the publishing interests around Adams had clearly seen a Hitchhiker’s Infocom game as a winning proposition all the way around. They had thus mobilized to make it part of their 1984 full-court press on their embattled author that had also yielded So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, the overdue fourth Hitchhiker’s novel. Infocom, meanwhile, had fortuitously paired Adams with Steve Meretzky, the most self-driven, efficient, and organized of all the Imps, who always got his projects done and done on time — as evidenced by his sheer prolificacy as an author of games, gamebooks, and lots and lots of fake memos. Even with Meretzky’s boundless creative energy on Infocom’s side, it had taken colluding with Adams’s handlers to isolate the two of them in a hotel in Devon to get Adams to follow his partner’s example and buckle down and work on the game.

With the industry now shifting under Infocom’s feet in ways that were hardly to their advantage, with Cornerstone threatening to sink the company even if they could find a way to keep selling lots of games, with the project in question a one-off that no one knew much about rather than another entry in the Hitchhiker’s line-up, Infocom lacked the leverage with Adams or his handlers to do anything similar for Bureaucracy. And Meretzky was staying far, far away, having apparently decided that he’d done his time in Purgatory with Douglas Adams and had earned the right to work on his own projects. Thus despite allegedly “working on” Bureaucracy personally for almost two years, despite all of the face-to-faces in Las Vegas, Nantucket, and London, Adams’s contributions at the end of that time amounted to little more than the rough idea he had brought to Infocom in the first place: the name, the blood-pressure monitor, and a few vague puzzle ideas like the boxes that sounded interesting but that no one other than him quite understood and that he never deigned to properly explain. Meretzky:

Douglas’s procrastination seemed much worse than it was with Hitchhiker’s. That seems odd because he did the first game only grudgingly, since he had already done Hitchhiker’s for several different media, but Bureaucracy was what he most wanted to do. Perhaps the newness and excitement of working in interactive fiction had worn off; perhaps he had more distractions in his life at that point; perhaps it was that the succession of people who had my role in Bureaucracy didn’t stay with the project for more than a portion of its development cycle and therefore never became a well-integrated creative unit with Douglas; perhaps it was that, lacking the immovable Christmas deadline that Hitchhiker’s had, it was easier to let the game just keep slipping and slipping.

Brian Moriarty is less diplomatic: “Douglas Adams was a very funny man, very witty, a very good writer, and also very, very lazy. Anyone who knew Douglas will tell you that he really didn’t like to work very much.” Just to add insult to injury, when Adams did rouse himself to work on a game project it turned out to be for a competing developer. In January of 1986 he spent several days holed up in London with a sizable chunk of the staff of Lucasfilm Games, contributing ideas and puzzles to their Labyrinth adventure game. That may not sound like the worst betrayal in the world at first blush, but consider again: he devoted more time and energy to this ad-hoc design consultation than he ever had to what was allegedly his own game, the one Infocom had started making at his specific request.

The succession of Imps who were assigned to the project were forced to improvise with their own ideas in face of the black hole that was Adams’s contribution. Details of exactly who did what are, however, once again thin on the ground. The only Imp I’ve heard claim specific credit for any sequence that survived into the final game is Moriarty, who remembers doing a bit where you’re trying to order a simple hamburger in a fast-food joint, only to get buried under a bewildering barrage of questions about exactly how you’d like it. The inevitable punchline comes when a “standard, smells-like-a-dog’s-ear burger with nothing on it” is finally delivered, regardless of your choices.

By late 1986, as the Bureaucracy project was closing in fast on its two-year anniversary, it was not so much a single big game as a collection of individual little games connected together, if at all, by the most precarious of scaffolding, each reading not like a game by Douglas Adams but a game by whatever Imp happened to be responsible for that section. Not only had Adams’s ideas for leveraging the mechanics of program and parser in service of his theme been largely abandoned, but at some point a fairly elaborate satire of paranoid conspiracy theorists — sort of an interactive Illuminatus! trilogy — had gotten muddled up with the satire of impersonal bureaucratic institutions in general. As the recent revelations about the National Security Agency have demonstrated, the two all too often do go together. Still, those parts of Bureaucracy had wandered quite far afield from everyday frustrations like trying to get a bank to accept a change-of-address form. It had all become quite the mess, and nobody had much energy left to try to sort it out.

If you had polled Infocom’s staff at this point on whether they thought Bureaucracy would ever actually be finished, it’s unlikely that many would have shown much optimism. The project remained alive at all not due to any love anyone had for it but rather out of what was probably a forlorn hope anyway: that getting this game out and published would pave the way to the next Hitchhiker’s game, to another potential 300,000-plus seller. Having done their part in getting Bureaucracy done, with or without Adams, Infocom hoped he would do his by returning to Hitchhiker’s with them. Few who knew Adams well would have bet much on that particular quid pro quo, but hope does spring eternal.

And then, miraculously, more than a glimmer of real hope did appear from an unlikely quarter. Marc Blank was long gone from Infocom by then, but had continued to keep in touch with his old friends among the Imps. At the November 1986 COMDEX trade show in Las Vegas, he bumped into Michael Bywater, a good friend of Douglas Adams and a fellow writer — in fact, a practitioner of his own brand of arch British humor that, if you squinted just right, wasn’t too different from that of Adams himself. Knowing the fix his old friends were still in with the game he had been the first to work on so long ago, a light bulb went off in Blank’s head. He hastily brokered a deal among Infocom, Adams, and Bywater, and the last arrived in the Boston area within days to hole up in a hotel room for an intense three weeks or so of script-doctoring. Infocom’s Tim Anderson, the latest programmer assigned to the project, stayed close at hand to insert Bywater’s new text and to implement any new puzzles he happened to come up with.

Jumbling the chronology as we’re sometimes forced to around here in the interest of other forms of coherency, we’ve already met Bywater in the context of his personal and professional relationship with Anita Sinclair and Magnetic Scrolls, and the salvage job he would do on that company’s Jinxter nine months or so after performing the same service for Infocom. As arrogant and quick to anger as he can sometimes be (one need only read his comments in response to Andy Baio’s misguided and confused article on the would-be second Hitchhiker’s game to divine that), everyone at Infocom found him to be a delight, not least because here at last was a writer who was more than happy to actually write. In a few weeks he rewrote virtually every word in the game in his own style — a style that was more caustic than Adams’s, but that nevertheless checked the right “British humor” boxes. Just like that, Infocom had their game, which they needed only test and publish to finally be quit of the whole affair forever. Right?

Well, this being the Game That Just Wouldn’t Be Finished, not quite. Janice Eisen, a current reader and supporter of this blog and an outside playtester for Infocom back in the day, recalls being given a version of Bureaucracy for testing that was largely the same structurally as the released version and that seemed to sport Bywater’s text, but that nevertheless differed substantially in one respect. The ultimate villain in this version, the person responsible for all of the bureaucratic tortures you’ve been subjected to, was not, as in the final version, a bitter computer nerd seeking to exact vengeance on the world and (for some reason) on you for his inability to get a date, but rather none other than Britain’s Queen Mother. As a satirical theme it’s classic Bywater. He was and remains a self-described republican, seeing the monarchy as setting “an appalling example to the whole nation by making clear that there’s at least one thing — head of state — that you can’t achieve but can only be born to.”

Some weeks after testing this version of Bureaucracy at home as usual, Janice, who lived close to Infocom’s offices, got a call asking if she could come in to test what would turn out to be the final version on-site. She was also told she could bring a friend of hers, another Infocom fan but not a regular tester, to join in. They spent a Saturday playing through the game, with a minder on-hand to give them answers to puzzles if necessary to make sure they got all the way through the game. It’s not absolutely clear whether Bywater was involved in the further rewriting made necessary by the replacement of the Queen Mother with the nerd, but the lavishly insulting descriptions of the latter — “ghastly,” “sniveling,” “ratty,” and “ineffectual” number amongst the adjectives — sound nothing like any of the Imps’ styles and very much like Bywater’s. When she asked why Infocom had made the changes — she had enjoyed the Queen Mother much more than the nerd — Janice was told that Infocom had feared that they were going too far into the realm of politics, that they were afraid that the Queen Mother, 86 years old at the time, might die while the game was still a hot item, making them look “terrible.” (This fear would prove unfounded; she would live for another fifteen years.)

So, it was a tortured, cobbled, disjointed creation that finally reached store shelves against all odds in March of 1987, and apparently one that had been subject to the final violation of a last-minute Bowdlerization. For all that, though, it’s a lot better game than you might expect, a better game even than most of the Infocom staffers, having had it so thoroughly spoiled in their eyes by the hell of its creation, are often willing to acknowledge. I quite like it on the whole, even if I have to temper that opinion with a lot of caveats.

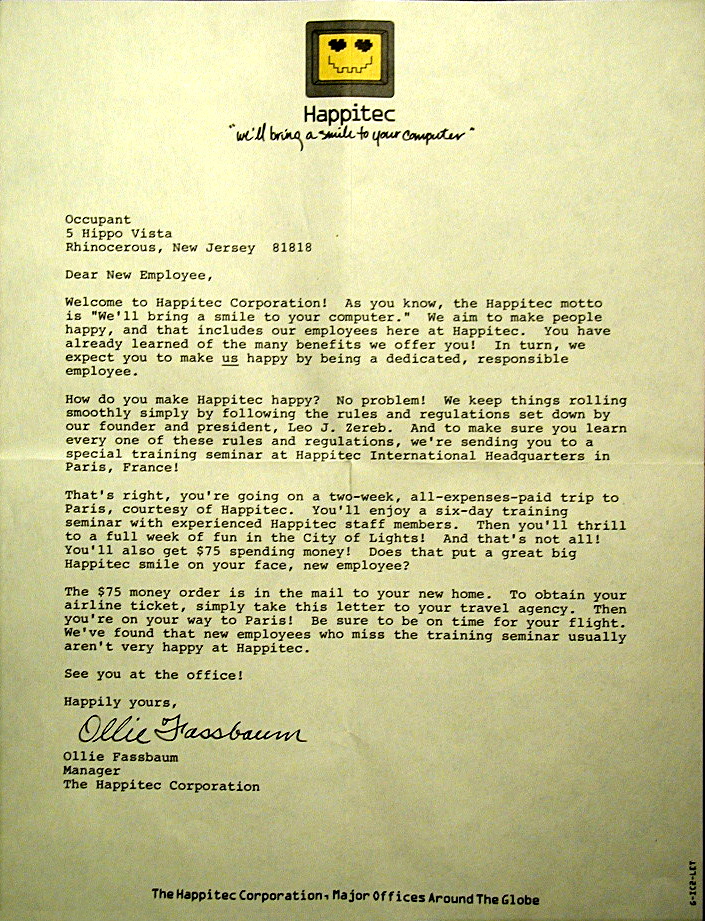

Bureaucracy shows clear evidence of the fragmented process of its creation in being divided into four vignettes that become, generally not to the game’s benefit, steadily more surreal and less grounded in the everyday as they proceed. The first, longest, and strongest section begins after you have just gotten a new job and moved to a new neighborhood. Your new employer Happitec is about to send you jetting off to Paris for an introductory seminar. You just need to “pick up your Happitec cheque, grab a bite of lunch, a cab to the airport, and you’ll be living high on the hog at Happitec’s expense.” Naturally, it won’t be quite that easy. It’s here that the game pays due homage to the episode that first inspired it: your mail had been misdelivered thanks to “a silly bit of bother with your bank about a change-of-address card.” Subsequent sections have you trying to board your flight at the airport; dealing with the annoyances of a transcontinental flight, which include in this case something about an in-flight emergency that will force you to bail out of the airplane; and finally penetrating the dastardly nerdy mastermind’s headquarters somewhere in the jungles of Africa.

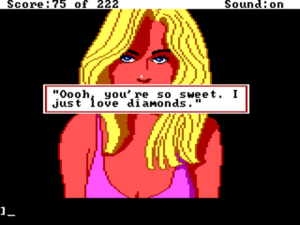

Much of Bureaucracy‘s personality is of course down to Bywater (about whom more in a moment), but I’m not sure that he comprises the whole of the story. I’d love to know who wrote my favorite bit, which is not found in the game proper but rather in one of the feelies. Your welcome letter from Happitec is such a perfect satire of Silicon Valley’s culture of empty plastic Utopianism that it belongs on the current television show of the same name. The letterhead’s resemblance to Apple’s then-current Macintosh iconography is certainly not accidental.

From the cult of personality around Happitec’s “founder and president” to the way it can’t even be bothered to address you by name to the veiled passive-aggressive threat with which it concludes, this letter is just so perfect. All it’s missing is a reference to “making the world a better place.”

Bywater, for his part, acquits himself more than well enough as the mirror-universe version of Douglas Adams, almost as witty and droll but more casually cruel. His relentless showiness makes him a writer whom I find fairly exhausting to try to read in big gulps, but he always leaves me with a perfect little bon mot or two to marvel over.

This is the living room of your new house, a pretty nice room, actually. At least, it will be when all your stuff has arrived as the removals company said they would have done yesterday and now say they will do while you're on vacation. At the moment, however, it's a bit dull. Plain white, no carpets, no curtains, no furniture. A room to go bughouse in, really. Another room is visible to the west, and a closed front door leads outside.

This deeply tacky wallet was sent to you free by the US Excess Credit Card Corporation to tell you how much a person like you needed a US Excess card, what with your busy thrusting lifestyle in today's fast-moving, computerised, jet-setting world. Needless to say, you already had a US Excess card which they were trying to take away from you for not paying your account, which, equally needless to say, you had paid weeks ago.

The stamp on the leaflet is worth 42 Zalagasan Wossnames (the Zalagasans were too idle to think of a name for their currency) and shows an extremely bad picture of an Ai-Ai. The Ai-Ai is of course a terribly, terribly rare sort of lemur which is a rare sort of monkey so altogether pretty rare, so rare that nobody has ever seen one, which is why the picture is such a blurred and rotten likeness. Actually, come to think of it, since nobody has ever seen the real thing, the picture might in fact be a really sharp, accurate likeness of a blurred and rotten animal.

The machine says: "Jones here. I'm the new tenant of your old house. There's a whole bunch of mail been arriving here for you. Urgent stuff from the Fillmore Fiduciary Trust. You know what I thought? I thought 'Do the right thing, Jones. Forward the guy's mail.' Then I found out about the termites. Then I found out about the nightly roach-dance. So I thought 'Rats.' I've returned your mail to your bank. Sort it out yourself."

So, when the scenario gives him something to work with Bywater can be pretty great. He’s much less effective when the game loses its focus on the frustrations of everyday existence, which it does with increasing frequency as it wears on and the situations get more and more surreal. He seems to feel obligated to continue to slather on heavy layers of snark, because after all he’s Michael Bywater and that’s what he does, but the point of it all begins rather to get lost. His description of your fellow passengers aboard an African airline as playing “ethnic nose flutes” is… well, let’s just say it’s not as funny as it wants to be and leave it at that. And his relentless picking away at the service workers you encounter — “The waiter squints at his pad with tiny simian eyes, breathing hard at the intellectual effort of it all.” — doesn’t really ring true for me, largely because I never seem to meet so many of these stupid and/or hateful people in my own life. Most of the people I meet seem pretty nice and reasonably competent on the whole. Even when I’m being gored on the bureaucratic horns of some institution or other, I find that the people I deal with are mostly just as conscious as I am of how ridiculous the whole thing is. As Kafka, who was himself an employee of an insurance company, was well aware, this is largely what makes bureaucracies so impersonal and vaguely, existentially horrifying. Ah, well, as someone who sees nothing cute about someone else’s baby — sorry, proud parents! — I can at least appreciate Bywater’s characterization of same as a “stupid, half-witted” thing emitting “hateful little bleats.”

The puzzles are perhaps the strangest mixture of easy and hard found anywhere in the Infocom catalog. The first two sections of the game are very manageable, with some puzzles that might almost be characterized as too easy and only a few that are a bit tricky; the best of these, and arguably the most difficult, is a delightful bit of illogical logic involving your bank and a negative check. When you actually board your flight and begin the third section, however, the difficulty takes a vertical leap. The linear run of puzzles that is the third and fourth sections of Bureaucracy is downright punishing, including at least three that I find much more difficult than anything in Spellbreaker, supposedly Infocom’s big challenge of a game for the hardcore of the hardcore. One is an intricate exercise in planning and pattern recognition taking place aboard the airplane (Bywater claims credit for having designed this one from scratch); one an intimidating exercise in code-breaking; one more a series of puzzles than a single puzzle really, an exercise in computer hacking that’s simulated in impressive detail. None of the three is unfair. (The puzzle that comes closest to that line is actually not among this group; it’s rather a game of “guess the right action or be killed” that you have to engage in whilst hanging outside the airliner in a parachute.) The clues are there, but they’re extremely subtle, requiring the closest reading and the most careful experimentation whilst being under, in the case of the first and the third of this group, time pressure that will have you restoring again and again. Bureaucracy raises the interesting question of whether a technically fair game can nevertheless simply be too hard for its own good. The gnarly puzzles that suddenly appear out of the blue don’t serve this particular game all that well in my opinion, managing only to further dilute its original focus and make it feel still more schizophrenic. I think I’d like them more in another, different game. At any rate, those looking for a challenge won’t be disappointed. If you can crack this one without hints, you’re quite the puzzler.

Although it’s Infocom’s third release in their Interactive Fiction Plus line of games that ran only on the “big” machines with at least 128 K of memory, Bureaucracy doesn’t feel epic in the way of A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity. A glance at the story file reveals that it doesn’t completely fill the extra space allowed by the newer Z-Machine, in contrast to the previous two games in the line that stuff the format to the gills. I would even say that quite a number of Infocom’s standard releases subjectively feel bigger. Bureaucracy became an Interactive Fiction Plus title more by accident than original intent, the extra space serving largely to give a chatty Michael Bywater more room to ramble and to allow stuff like that elaborate in-game computer simulation. And given the way the game was made, I’d be surprised if its code was particularly compact or tidy.

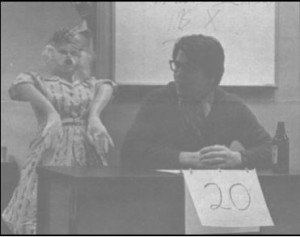

Despite all of the pain of its creation and the bad vibes that clung to it for reason of same, Infocom released Bureaucracy with relatively high hopes that the Douglas Adams name, still printed on the box despite his minimal involvement, would be enough to sell a substantial number of copies even absent the Hitchhiker’s name. Adams, showing at least a bit more enthusiasm for promoting Bureaucracy than he had for writing it, gave an interview about it to PBS’s Computer Chronicles television program, during which it becomes painfully apparent that he has only the vaguest notion of what actually happens in the game he supposedly authored. He also appeared on Joan Rivers’s late-night talk show; she declared it “the funniest computer game ever,” although I must admit that I find it hard to imagine that she had much basis for comparison. None of it helped all that much. As was beginning to happen a lot by 1987, Infocom was sharply disappointed by their latest hoped-for hit’s performance. Bureaucracy sold not quite 30,000 copies, a bit better than the Infocom average by this point but short of Hitchhiker’s numbers by a factor of more than ten.

The game’s a shaggy, disjointed beast for sure, but I still recommend that anyone with an appreciation of the craft of interactive fiction give it a whirl at some point. If the hardcore puzzles at the end aren’t your bag, know that the first two sequences are by far its most coherent and focused parts. Feel free to just stop when you make it aboard the airplane; by that time you’ve seen about 75 percent of the content anyway. Whatever else it would or should have become, as Infocom’s only work of contemporary social satire Bureaucracy is a unique entry in their catalog, and in its stronger moments at least it acquits itself pretty well at the business. That alone is reason enough to treasure it. And as a lesson in the perils of staking your business on a single mercurial genius… well, let’s just say that the story behind Bureaucracy is perhaps worthwhile in its way as well.

(As usual with my Infocom articles, much of this one is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Reader Janice Eisen took the time to correspond with me about her memories of testing Bureaucracy, for which I owe her huge thanks. Other sources include the two Douglas Adams biographies, Hitchhiker by M.J. Simpson and Wish You Were Here by Nick Webb; the Family Computing of September 1987; the Electronic Games of April 1985; and the audio of Steve Meretzky and Michael Bywater’s joint conversation in London back in 2005.)