February 3, 1976

An Open Letter to Hobbyists

To me, the most critical thing in the hobby market right now is the lack of good software courses, books, and software itself. Without good software and an owner who understands programming, a hobby computer is wasted. Will quality software be written for the hobby market?

Almost a year ago, Paul Allen and myself, expecting the hobby market to expand, hired Monte Davidoff and developed Altair BASIC. Though the initial work took only two months, the three of us have spent most of the last year documenting, improving, and adding features to BASIC. Now we have 4 K, 8 K, Extended, ROM, and Disk BASIC. The value of the computer time we have used exceeds $40,000.

The feedback we have gotten from the hundreds of people who say they are using BASIC has all been positive. Two surprising things are apparent, however: 1) most of these “users” never bought BASIC (less than 10 percent of all Altair owners have bought BASIC), and 2) the amount of royalties we have received from sales to hobbyists makes the time spent on Altair BASIC worth less than $2 per hour.

Why is this? As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?

Is this fair? One thing you don’t do by stealing software is get back at MITS for some problem you may have had. MITS doesn’t make money selling software. The royalty paid to us, the manual, the tape, and the overhead make it a break-even operation. One thing you do do is prevent good software from being written. Who can afford to do professional work for nothing? What hobbyist can put three man-years into programming, finding all the bugs, documenting his product, and distribute for free? The fact is, no one besides us has invested a lot of money in hobbyist software. We have written 6800 BASIC, and are writing 8080 APL and 6800 APL, but there is very little incentive to make this software available to hobbyists. Most directly, the thing you do is theft.

What about the guys who resell Altair BASIC, aren’t they making money on hobbyist software? Yes, but those who have been reported to us may lose in the end. They are the ones who give hobbyists a bad name, and should be kicked out of any club meeting they show up at.

I would appreciate letters from anyone who wants to pay up, or has a suggestion or comment. Just write me. Nothing would please me more than being able to hire ten programmers and deluge the hobby market with good software.

Bill Gates

General Partner, Micro-Soft

The “open letter” above, written by a 20-year-old Bill Gates, was printed in early 1976 in a number of the publications that served the nascent PC industry, centered at the time on the MITS Altair kit computer. Some of the soldering-iron-wielding visionaries who read it were enraged, a few supportive. Most, however, were merely confused. Sharing, of software the same as all other sorts of information, was simply what they did, the rock upon which their little hacker community was founded. For many the letter marked the first time they had ever confronted the notion of a program being owned by a single entity.

The PC industry was barely a year old, but already its age of innocence was passing. Bill Gates, the man who brought knowledge of the good and evil of copyright to this hacking Eden, was, plenty would soon be arguing, perfectly suited to play the role of the serpent. The change in thinking he set in motion with this open letter of his would soon prove more significant than even his own company’s outsized influence on the industry. From 1976 right up to the present day — and doubtless for many years to come — the PC industry and all of its many offshoots have been tying themselves into knots over the question of copyright, of where the ethical and legal rights of digital-content creators and users begin and end.

Both sides of the debate as it rages today could stand to glance back at copyright as it was once understood. Those who claim that modern copyright law merely applies an eternal principle to a new medium should note that, on the contrary, our notions of copyright have changed in some very fundamental ways in recent decades. And those who see laws like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act as well-nigh fascistic overreaching might do well to remember that even in the pre-DMCA days one could be prosecuted for merely photocopying the pages of a book. At the first conference on “software protection” in Britain in 1981, the first speaker opened with an old joke about an Englishman who asks an Irishman how to get to County Derry. “If I wanted to get to County Derry,” replies the Irishman, “I wouldn’t start from here.” The decades after Bill Gates fired the opening salvo of the digital-copyright wars would be marked by the law’s struggle to get to there from here — from the analog, materialist culture of creation that was to the digital, virtual culture that must now be.

When thinking about any big, overarching concept like that of copyright, it’s often helpful to return to first principles, to think about what the words or phrases themselves literally mean. In those literal meanings we can usually find the meaning of the concept as its originators understood it. Just as, say, “science fiction” once literally meant fiction about science, “copyright” once meant simply the right to copy. As enshrined in the American Copyright Act of 1909, the latest iteration at the time that Bill Gates wrote his open letter of the original Act of 1790, only the author had the right “to print, reprint, publish, copy, and vend the copyrighted work.” The original sin that must come before any printing, reprinting, publishing, or vending by someone who wasn’t the author must be the simple act of copying itself, which was in and of itself illegal. If you purchased a book at your local bookstore and copied its contents — whether on a photocopier, on a typewriter, or freehand on paper — you had already committed an actionable legal offense, even if your purpose in doing so was simply to have a “backup” copy for your own personal use. In the materialist world of arts and letters that held sway prior to the digital revolution, this approach to copyright as a literal right to copy made perfect sense.

Many of the conflicts and controversies that have plagued the idea of copyright in the years since have stemmed from the fact that a right to copy is a prerequisite to making any use at all of digital content. Thus rights-holders have needed to make the act of unauthorized distribution, not that of unauthorized copying, the original sin of the infringer. Much of the story of recent copyright legislation has been the story of how that shift was made.

On this blog, we’ve heretofore largely avoided that long, fraught societal debate and negotiation, but the specter of copyright and its violation in the form of software piracy loomed too large over the games industry of the 1980s to neglect it any more. This, then, is the story of what Gates’s letter wrought for the people who were making the games, the people who were playing them, and, in due time, an underground culture which dedicated itself to defying the legal system and keeping games — all games — available for free.

The first programmer ever to attach a notice of copyright to her program, and thus quite likely the first programmer ever to conceive of her program as a potentially marketable creative work, was Betty Holberton, one of the original programmers of the ENIAC, by some definitions the world’s first true computer. In 1951, she was proud enough of a sorting program she had written to attach her name to a copyright notice included therein. It wasn’t until 1964, however, that a programmer made the next step of attempting to actually secure registration through the Copyright Office. That year a Columbia University law student and MIT electrical-engineering graduate named John F. Banzhaf III applied for the registration of two programs he’d written to aid his studies: one to help with the indexing of old court cases and one to compute automobile braking distances. His request was at first rejected, but he put his legal training in progress to good use to lobby for reconsideration. At last a Copyright Office functionary decided that “we could, under the law, make the registration.” The whole transaction was novel enough that the New York Times printed a rather bemused sidebar about it.

Despite Banzhaf’s success, few followed his lead in using copyright as a means of protecting their investment in software. IBM and the other companies who made the big-iron systems that kept the books for corporate America saw their programs not so much as independent entities as components of an entire ecosystem which included both hardware and software. They offered the whole enchilada to their customers as a leased package, complete with lengthy, heavily restrictive licensing agreements that can be seen as the forefathers to all the legalese we click through so impatiently today every time we install a new piece of software. If those contracts, many of which had never been tested in court, should fail, there were always patents, of which IBM in particular had quite a massive portfolio covering most of their systems’ operations.

Meanwhile the smaller systems with their scruffier, more independent-minded hacker culture were so immersed in the ethos of sharing ideas and code alike that copyright was a veritable foreign concept to them. Anyway, what would be the point of copyright really? Nothing like commercial software as we know it today existed prior to the mid-1970s. You either got your software along with your hardware from a big vendor like IBM, you wrote it yourself, or you pulled it off the hacker grapevine. You certainly didn’t walk into a store and buy it.

It was probably a good thing that the copyrighting of software felt a little pointless because, Banzhaf’s success with the Copyright Office aside, it wasn’t at all clear that the current copyright law could even be applied to much or all software due to two serious concerns.

The first was the stipulation, stated in the text of the 1909 Act, that copyright applied only to the “writings of an author.” The body of amendments and case law that followed had determined that “writings” encompassed not just traditional literary works but also such creative miscellany as musical compositions and recordings, statues, films, photographs, scientific models, and maps. Multifarious as they were, these forms all had one trait in common: they could all be easily “read” by a human being with the right knowledge or training. Program source code should also qualify under this standard.

But the proprietary software that was most likely to need the protection afforded by copyright wasn’t always distributed as source code. The sequences of ones and zeroes that made up binary code could be read only slowly and laboriously — anything but “easily” — by even the most talented hackers. One might be tempted to make a comparison to film, which like computer programs did require a technological intermediary to be “read” by people but which clearly was covered by copyright thanks to a 1912 amendment to the Act of 1909. Yet the comparison broke down in the question of just what it was that the author was really seeking to copyright. In the case of a film, that was the presentation layer, if you will, the actual imagery being projected onto the screen. In the case of something like Bill Gates’s BASIC, it was the code that generated what appeared on the screen. A comparison with recorded music broke down similarly. Yes, with computer displays so primitive as to make it difficult to distinguish one program from another, it was the code that mattered to companies like the young “Micro-Soft” — and, indeed, that would remain the main if not the exclusive nexus of their attention for many years to come.

The best hope for dodging the requirement of human readability lay in the fact that the copyright to an original work also reserved to its author the exclusive right “to translate the copyrighted work into other languages or dialects, or to make any other version thereof.” Without too much tortured thinking, one could imagine a compiler as “translating” source code into another version, a derivative work — albeit one not human-readable — also covered by the copyright to the original source. Unfortunately, case law seemed to point against such an interpretation. In 1908, the Supreme Court had decided in the case of White-Smith Music Publishing v. Apollo that a player-piano roll, which one might see as analogous to binary code, was not eligible for the same copyright protection as the sheet-music “source code” that had produced it.

And that was if anything the easier legal question. The other concerned the fundamental idea of copyright itself as it was still understood by the law in 1976 — that of it constituting a literal “right to copy.” The thing was, a program was copied every single time it was run — copied from disk or tape or, in the case of Altair BASIC, a spool of punched paper into the memory of the computer. This act would seem to be according to the established law clearly illegal, just as much so as buying a book and photocopying its pages. Thus every legitimate purchaser of Altair BASIC who chose to actually use it immediately became a pirate.

Now, this loophole was at some level fairly ridiculous, sounding more like a gotcha! for a raging pedant than a serious argument for those of good faith. Yet, ridiculous as it was, it was also extremely dangerous. How could a company like Microsoft claim the right to ask people to ignore this part of the law, but not these other parts? A slippery-slope scenario could be all too easily imagined. Even worse, as long as it existed, as long as a law hadn’t been written to explicitly close it, the loophole remained as a legal land mine for any company contemplating the ultimate remedy against piracy, that of hauling the pirates into court; a clever defendant could point to it and collapse the whole concept of copyright as applicable to software at a stroke.

Even as Bill Gates was drafting his letter, Congress was in the process of overhauling American copyright law for the first time in well over half a century. Yet the end result directly answered few of the burgeoning software industry’s concerns. In addition to dramatically extending the term of copyright protection from a maximum of 56 years to “the lifetime of the author plus 50 years,” the Copyright Act of 1976, which actually went into effect on January 1, 1978, further broadened the applicability of copyright to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” While the Act still failed to cite software among its many examples of same, it seemed more clear than ever that source code at least ought to fit this definition of a copyright-eligible work, while the door for binary code now also seemed, at worst, to have been opened considerably wider. But an unresolved question still remained in the form of the negative legal precedent of White Smith v. Apollo. And the copying that was a necessary part of actually running a computer program remained unaddressed as well.

The software industry therefore started working on solving the problem through technical rather than legal means. Here Bill Gates’s Microsoft was once again at the fore. When Microsoft shipped their version of Will Crowther and Don Woods’s perennial Adventure for the TRS-80 in 1979, they included on the disk one of the first instances of physical copy protection, on the theory that if buyers couldn’t copy the disk in the first place they wouldn’t be tempted to share the game with their friends. Ironically, Microsoft’s own ethical if not legal right to sell Crowther and Woods’s game was far from clear, a classic example of the moral murkiness that always seems to surround issues of piracy and intellectual property in the digital age as soon as you drill beneath the surface.

Only in 1980, with the PC industry beginning to enter the public consciousness as a much-needed American economic-success story and Apple, whose origins in a suburban garage were already becoming the stuff of legend, gearing up for the first big silicon IPO, did Congress at last directly address the question of copyright as it applied to software. The Computer Software Copyright Act of 1980 created an exception in the case of software to the idea of copyright as fundamentally constituting an author’s exclusive right to copy. Henceforward, said the Act, “it is not an infringement for the owner of a copy of a computer program to make or authorize the making of another copy” if such a copy is “an essential step in the utilization of the computer program” — thus securing the owner’s right to actually run the software she purchased — or is “for archival purposes only” — thus securing the owner’s right to make backup copies of her purchase. Making the act of distribution rather than the act of copying itself the original sin of software piracy represented a huge development in the evolution of copyright law that went as unremarked by the Act’s own drafters as it remains today. The law’s oft-tardy, clunky, and controversial negotiation with the brave new world of digital content begins here, in a modest little change that even most Congresspeople barely even noticed.

That same year, the question of whether the presentation layer of a program can be afforded copyright protection in its own right was settled in the affirmative in a landmark court case involving Midway, a producer of standup-arcade games, and Dirkschneider, a cloner of same. Atari in particular immediately started applying that precedent with gusto to squash the practice of cloning their standup-arcade and home-console games on computers.

All told, it had been a pretty good year for those on the side of strong software-copyright protection. But still hanging out there at its end, unresolved and dangerous and with case-law precedent still seemingly against it, was the question of copyright protection for binary code.

For a long time the question continued to go unresolved, even as IBM entered the PC fray and the software industry went from being a curiosity to one of the biggest stories in the world of business, with names like WordStar and VisiCorp — and, yes, Microsoft — now on every stockbroker and venture capitalist’s lips. But then in 1982 along came a company called Franklin Computer which wished to produce a clone of the Apple II. By far the most difficult part of such a task must be the production of a ROM-based operating system that performed exactly like Apple’s own; the slightest deviation would mean that a subset of the Apple II’s huge software library must fail to work on Franklin’s model. Franklin responded to the challenge through the simple expedient of copying Apple’s ROM verbatim, whereupon Apple responded to Franklin’s solution by suing them in federal court. Franklin didn’t even try to deny that they’d copied Apple’s own ROM — but, they claimed, they were within their rights to have done so. At the root of their complicated defense was the old claim that copyright could not be applied to binary code. The industry held its collective breath; the moment they had half wished for and half dreaded for so long was here. At last the long-standing question was about to be settled in court.

Things didn’t go so well at first. The district court refused an injunction by Apple to force Franklin to take their machines off the market, and then ruled for Franklin in open court, accepting their argument that binary code could not by its nature be subject to copyright — exactly the result the industry had feared. But Apple appealed, and finally, on August 30, 1983, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Franklin had indeed violated Apple’s copyright, at the same time definitively settling in the affirmative the question of whether binary code could be copyrighted. Citing the 1976 Act’s stipulation that copyright could also be applied to works readable only “with the aid of a machine or device,” the Court stated that “it is clear from the language of the 1976 Act and its legislative history that it was intended to obliterate distinctions engendered by White-Smith.” Franklin was forced to withdraw their machine from the market until they had written for it a unique ROM of its own. The question of the copyright eligibility of binary code would never be seriously challenged again.

Relatively little remembered today, Apple v. Franklin was, in terms of its impact on the industry at large, easily one of the most significant court cases with which Apple has ever been involved. It had taken more than seven years to get from Bill Gates’s open letter to this point, but the American software industry could at last feel entirely free to zealously guard their intellectual property and sue offenders, with both law and precedent on their side. The rest of the Western world gradually followed the American legal system’s lead. In 1985, for instance, the British Parliament passed the Copyright (Computer Software) Amendment Act, securing once and for all the same strong copyright protection for companies selling their software on British soil.

Yet, even with the legalities finally settled, it made little sense to attempt to prosecute most software pirates. Civil or criminal court cases involving software piracy, both in the United States and outside it, remained a relative rarity, reserved for large-scale bootlegging rings and blatant corporate violators like Franklin. Game publishers in particular, a small fraction of the software industry as a whole, lacked the time, money, and energy to legally pursue on any serious scale the mostly teenage pirates who passed games among themselves in school lunch rooms and via the BBS networks. While the threat of legal action always made a good rhetorical tool — “It could happen to you!” — game publishers, following the lead of Microsoft Adventure, came to rely on technical rather than legal remedies to minimize the damage. Their methods encompassed various sorts of manual-look-up schemes — photocopying was still fairly expensive in the 1980s — as well as code wheels, hardware dongles, and bizarre Rube Goldberg contraptions like the British Lenslok. But the bedrock for most publishers remained the protection they applied to the disk or tape itself to make it physically impossible to copy. Virtually all publishers understood that their protection schemes, whatever form they took, were bound to be broken. One hope was that the protection would hold up for at least a little while under the onslaught of the hardcore crackers; another was that it would be enough in and of itself to deter the more casual pirates. The former hope was usually forlorn, while the latter stood on moderately firmer ground.

Meanwhile the larger debate about the rights of software buyers and sellers that had been touched off by Bill Gates’s letter was far from over. Indeed, it continued to rage more violently than ever at users group meetings, in computer stores, and in the magazines, pitting the software industry against a substantial percentage of their theoretical customer base. In 1983 a new Apple II magazine called Hardcore Computist chose to begin publishing information on copy-protection schemes and how to crack many of the most popular games. The response from the software industry was a shitstorm that forced the magazine off of computer-store racks and drove it underground. As a largely subscription-only publication, the editors chose to double down on their stance that a right of users to make backup copies of their expensive software ought to be as fundamental as the right of publishers not to have their programs given away for free. Hardcore Computist quickly became a go-to source for Apple II crackers, both those wanting simply to make the personal backups the law so plainly allowed and those with more nefarious agendas.

That magazine was, however, very much the exception. The others, knowing who buttered their bread, duly toed the industry hard line against any and all forms of copying, with very few exceptions. To do otherwise risked becoming a pariah like Hardcore Computist, cut off from the advertisements, early review copies, and insider scoops on which they depended. Few editors dared to push back in more than the most tepid ways against the industry’s stance. The articles they published on the subject usually weren’t all that different in tone or content from Bill Gates’s original entry in the genre, complete with questionable data (“Industry estimates claim that between four and ten illegally copied programs are circulating for every one sold.”); dire predictions for the future (“Software piracy, which was the casual crime of the 1980s, could actually threaten the survival of the software industry in the 1990s.”); conflations of piracy with shoplifting (“It seems that the same person who would never dream of walking out of a K-mart with a stolen watch hidden in his jacket doesn’t think twice about stealing software.”); fear-mongering (“Those who dip into the questionable waters of pirated software risk virus infection each time their disk drive whirs.”); and a little good old-fashioned name-calling (“Those computerists who copy software are the lowest form of animal life on the planet.”). A more candid debate was allowed to rage only in the letters sections, where the pirates, usually in response to a hand-wringing anti-piracy editorial or feature article, got a chance to state their side of the case.

The core of their argument, one which carried with it a certain practical if not always a legal or moral force, was that games were ridiculously overpriced, and that most of them were terrible to boot. Both assertions were largely correct. The price you pay today per man-hour of game-developer effort is almost invariably well over one if not two orders of magnitude less than it was in the 1980s even without adjusting for inflation. This reality applies almost equally to the good games of yore, the games I’ve praised here, as the bad. Even the typical Infocom game gave you about a novella’s worth of text, various “you can’t do that!” messages included, in return for $30 to $50 in 1980s money. The nostalgic stories of the old days that abound in places like the Get Lamp documentary claim that players routinely got 50 or 100 hours out of such thin gruel, but it’s honestly hard for me to imagine how. And, again, those are the good games. Many others were all but unplayable, insoluble, or missing vital clues due to the fact that most publishers’ testing methodology consisted of “let the developers play it for a few days if there’s time, otherwise just put it in a box and ship it.” Games routinely shipped with flaws serious enough almost to smack of outright fraud, flaws that not even the most mercenary publisher of today would dare allow to go unaddressed. And the magazines, in thrall as they were to the publishers for advertising dollars, were hardly a reliable means of sorting the wheat from all that chaff. The economics of gaming being so hopelessly out of whack, many pirates claimed that they copied games only to test them out and see if they were really worth the money, that they then bought those few that they did indeed judge worthy. Assuming they were telling the complete truth — admittedly a doubtful proposition — this seems to me quite a reasonable response to the situation.

Which is not to say that game publishers were deliberately shafting their customers. Staying in business carries plenty of fixed costs, and requires much larger profit margins when selling 50,000 copies of a successful game rather than 5 million or more. Everyone was doing the best they could, but everyone was feeling their way through, without any precedents to guide them. It was hard for a gamer, eager to play all the latest games highlighted in the magazines, to take too seriously the moral hectoring of the editors of same who were themselves drowning in free review copies.

Underlying the whole debate, conducted though it often was in such strident fashion on both sides, was an uneasy settlement. Publishers recognized that their software was going to be copied and traded, but, through physical copy protection and other means, hoped to keep it to a manageable level. Meanwhile users settled into whatever approach best seemed to balance ethics and practicalities: set up a collective with a few friends to buy a pool of games and trade them with each other; buy every third Infocom game and pirate the others from the BBS network; buy a game if and only if you wound up spending more than a few hours with the pirated version; etc.

But of course there were also the hardcore pirates, the people who wanted to have every game released, who tied their self-worth to the number of “hot warez” in their collection. For them the act of collecting games, not that of playing them, was the real draw. Many would say that the greatest game of all was the one played between the crackers, the elite members of the piracy “scene” who knew how to break copy protection, and the publishers, who were constantly dreaming up nastier and trickier schemes to protect their disks. The scene’s shadowy existence was barely hinted at by the bright, wholesome magazines chronicling the overground of computing. But, existing in a zone between the casual pirates who traded games with their friends and the big for-profit bootlegging rings, the scene was responsible for virtually all of the cracks that gradually trickled down to even many of the least-connected gamers, making it the root of all the evils of piracy in the view of the publishers. And yet, decentralized and anonymous as it was, it was impossible for them to stamp out. Described by historian Anders Carlsson as nothing less than “the first digital global subculture,” the scene was, among other things, a cesspool of adolescent nihilism, teenage posturing, and crude social Darwinism, teeming with racism, sexism, and homophobia. It was, in other words, much like many other gatherings of unsupervised teenage boys. Nevertheless, it’s thanks only to the efforts of the scene’s crackers that many of the games I write about still exist at all for an historian like me to study — one more ironic aspect of an intellectual-property debate that’s never quite as ethically clear as either side would have it. We’ll look more closely at this mysterious scene, at where it came from and what it meant to 1980s gaming, next time.

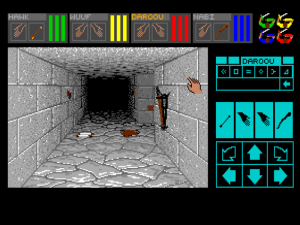

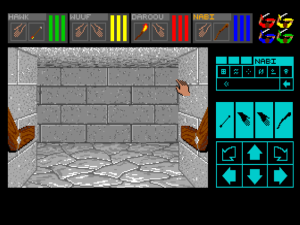

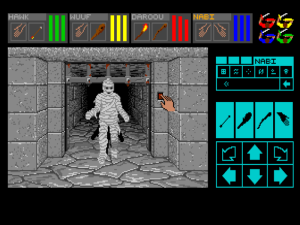

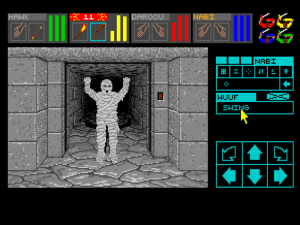

(Sources: ACM Computing Surveys of March 1975; New York Times of May 8 1964; Byte of September 1976, January 1977, May 1981, September 1981, October 1981, December 1981, January 1982, and May 1982; PC Magazine of October 1982 and November 1982; Computer World of December 5 1983; 80 Microcomputing of November 1982, February 1983 and April 1983; Ahoy! of August 1985, November 1985, and March 1986; Color Computer Magazine of August 1983, November 1983, January 1984, and July 1984; Commodore Magazine of April 1989; Commodore Power Play of August/September 1985; Games Machine of September 1988; Transactor 5.3 and 5.5; Computer Gaming World of September/October 1982; Acorn User of September 1984; Amazing Computing of September 1987; A.N.A.L.O.G. of January 1984; Computer and Video Games of April 1984, May 1984, and June 1984; Creative Computing of November 1984; Electronic Games of January 1985; Enter of April 1984; Hardcore Computist #2; New Zealand Bits and Bytes of September 1982; Popular Computing Weekly of June 7 1984; Sinclair User of September 1984 and November 1984; The Rainbow of March 1984; Your Spectrum of December 1983/January 1984; Zzap! of June 1987. Also the book From Pac-Man to Pop Music, including “Chip Music: Low-Tech Data Music Sharing” by Anders Carlsson. The pictures are all drawn from the magazines’ various anti-piracy articles, which always seem to bring out the fanciful best in their artists. Really, aren’t they great?)