I’m a game player, mostly, that’s about it. I’m pretty dull, actually.

— Joel Billings

Joel Billings is about as close to a literal lifelong gamer as it’s possible to be. His father taught him to play the old Avalon Hill wargame classic Tactics II in 1965, when he was just 7 years old. Robert Billings, who regarded gaming only as an occasional pleasant diversion, soon had cause to wonder whether that introduction has been a wise move; young Joel got obsessed right from the first. Instead of playing with cars or model trains, Joel re-fought the major battles of World War II and the American Civil War on his bedroom floor, having simultaneous and almost equally pitched real-world battles with the family dog, who wanted to play too. While other boys played sports, or merely watched them, Joel was determined to simulate them. He tried to recreate every single game of the 1969 football season for every single team — hundreds of individual matches — using Strat-O-Matic Football, finally stopping out of sheer exhaustion with just twenty or so matches left to play. Encouraged to find a more social outlet for his “hobby,” he raided his high school’s chess club to form a wargaming club with himself as founder, president, and, it seems safe to say, most passionate member by a country mile. The same could be said of the company he would later found.

But it was awfully hard in those early days for Joel or anyone in his family to imagine how he could turn his passion into a living wage, especially given that he wasn’t and would never be so much a start-from-scratch designer as an avid, gifted player. After doing well at his suburban Los Angeles high school despite the lure of wargames — he graduated 19th in a class of 572 — he proceeded to Claremont Men’s College in 1975 to pursue a degree in Economics. There he continued with his beloved wargames, betwixt and between and every chance he got. He would sometimes enter three divisions of a wargaming tournament simultaneously, an obligation later described by Al Tommervik of Softalk magazine as “roughly akin to playing a couple of dozen simultaneous chess matches against near masters.”

The late 1970s were a good time to be a wargamer. In terms of dollars and cents, this period was the tabletop-wargame industry’s golden age. Annual sales grew at a rate of 40 percent or more for the better part of the decade, peaking in 1979 at $15.5 million. Those may sound like small numbers in comparison with many another entertainment industry, but for wargaming, always the very definition of a niche hobby, they were very good ones indeed in comparison to what had come before and, less happily, what would soon follow. Surveys reckoned over a quarter of a million Americans were active wargamers, with an average age of just 22 years. (In the years to follow, one of those numbers would plummet while the other rose precipitously.) Joel Billings — smart, from comfortable circumstances, and 21 years old in 1979 — was practically the prototypical specimen of the breed.

In those days wargaming was absolutely dominated by a Coke and a Pepsi, whose combined sales accounted for 80 percent of the industry as a whole. Wargaming’s Coke was Avalon Hill, the big, traditionalist institution whose Tactics, generally regarded as the urtext of the modern wargame, had birthed the industry back in 1954. Its Pepsi was the younger, slightly smaller, slightly hungrier, arguably more innovative Simulations Publications, Incorporated, universally known as SPI. The two companies were each regarded with great love and loyalty by their respective fans, who felt they could discern a distinct personality not only in the marketing and packaging of each company’s games but in the games’ rules as well. Plenty of wargamers were stalwart loyalists to one camp or the other, refusing to buy or play a game by the rival company. Joel wasn’t quite that extreme, but was always an Avalon Hill man when push came to shove.

Joel Billings, the man destined to bring the culture of chits and dice into collision with that of bits and bytes, had his first run-in with computers early in his time at Claremont College. He wound up, more by happenstance than desire, in a BASIC programming class conducted with the mediation of a big DEC PDP-10. This first encounter didn’t rock his world the way it did that of so many characters we’ve met on this blog — Joel had already found his lifelong passion when he had first played Tactics II all those years ago — but he did find the experience interesting, and found he had a certain aptitude for it as well. It started him to musing about the changes computers might wreak on his own favored hobby. For his final project in the class, he wrote a simple little two-player tank game. It was a wargame in only the most generous definition of the term, but it was a start. In the meantime, he parlayed that class into a six-month internship at Amdahl Corporation, a maker of mainframe computers located in Silicon Valley, during his senior year at university.

After graduating from Claremont College in May of 1979, Joel traveled up the coast again to take a summer job with Amdahl before he went on to graduate school at the University of Chicago. As he had before, he stayed in a spare apartment above the house of David Rubinfien, an uncle. Immersed in the world of big mainframe iron as he was, Joel had only recently become aware of the nascent PC revolution. But as soon as he’d seen his first TRS-80 he’d begun wondering what these new microcomputers might be able to do for his hobby. Rubinfien, as always supportive of and helpful to his nephew and possessed of some connections in the Valley to boot, encouraged him to find out.

Joel first talked to some programmers who worked for IBM, but they told him flat-out that his idea of creating a wargame reminiscent of the tabletop games he loved on the microcomputers of the day was absurd. Undaunted, Joel hung flyers in several of the local computer shops. With the moment of decision looming ever closer — did he stay here and try to make a computerized wargame or did he go off to graduate school? — he was contacted in early August by one John Lyon. Eighteen years Joel’s senior, Lyon was an experienced programmer currently working for Control Data who loved wargames almost as much as Joel. He had never programmed a microcomputer before, but he didn’t let that stop him. “This is what opportunity looks like when it knocks,” Lyon had told the sales clerk standing by the store’s bulletin board. “And I’m going to answer it.”

Pressed for time as they were, Joel and John settled on a rather blatant computerized clone of an old Avalon Hill classic called Bismarck, a simulation of the legendary German battleship‘s ill-fated attempt to break out into the Atlantic shipping lanes in 1941. In addition to offering a completed design to start from, Bismarck seemed ideal in a number of other ways. For one thing, its was a popular subject known even to many non-military-history buffs thanks to the classic war flick Sink the Bismarck! But there were also other, less obvious considerations. Joel had long since realized that the computer had the potential to bring two hugely salable advancements to the traditional tabletop wargame, and a Bismarck game would be well-nigh ideal for demonstrating both of them.

One advancement would be true hidden movement. Implementing a proper “fog of war” presented an obvious problem for a tabletop wargame where each player was tracking moves on the same game board and needed to be able to make sure the other wasn’t cheating. The problem of fog of war was so vexing yet so essential to any realistic simulation of military conflict that some of the most elaborate wargames had taken to requiring a third participant, a referee who could serve as a neutral arbiter and keep track of each player’s units in relation to the others; you can imagine how popular that thankless role was. A computerized version of Bismarck could demonstrate to fine effect the computer’s ability to simulate the fog of war. Indeed, one might say that this entire scenario revolved around the fog of war: the really difficult part for the British side was simply finding the Bismarck. The British forces were so overwhelming in comparison to the German that, as Joel puts it, “if you find the Bismarck you’re likely to kill it.”

The other advantage computers brought to the (non-)table was of course to eliminate not only the need for a referee but also the need for another player, to provide an artificially intelligent opponent who was up for a game any time you were. Artificial intelligence was, however, a hard task to shoehorn into a microcomputer of 1979 vintage. It was here that the second big advantage of Joel and John’s choice of games came in: with a Bismarck game, they really didn’t need much of an artificial intelligence at all. The order of battle for the German side of things consisted of only the Bismarck itself and a single escorting cruiser; the tiny flotilla’s strategic and tactical options were pretty much limited to “sail as quickly as possible and hope the British forces don’t find them.” Surely the computer could manage that much. All John Lyon needed do was restrict the human player to only playing the British side.

Computer Bismarck was programmed in Joel’s apartment at the top of this rather hair-raising staircase. Thanks to an adolescent bout with polio, John Lyon had to climb it on crutches every evening.

Lyon set to work programming the game, using only text because that’s all the borrowed North Star CP/M machine he and Joel had scrounged could manage; neither of these two would-be microcomputer-software impresarios yet owned an actual microcomputer. Meanwhile his uncle set up several meetings with venture capitalists, which didn’t yield any immediately tangible results. But then the Silicon Valley grapevine reached Trip Hawkins, a young man only a few years older than Joel who worked for a company Joel had barely heard of to this point: Apple Computer. A venture capitalist called Hawkins to tell him about this interesting proposal that was coming from an inexperienced youngster with questionable credentials to pull it off. If Hawkins would quit his job at Apple and become president of the new company, the venture capitalist said, he could guarantee him ample financing. Hawkins wasn’t ready to do any such thing, but he was intrigued enough by the venture capitalist’s description to meet with Joel.

The two were polar opposites in temperament, Hawkins charismatic, nakedly ambitious, and dynamic while Joel was quiet, staid, and thoughtful. Both, however, had grown up similarly steeped in the games culture of the 1960s and 1970s. Eager to foster the games industry that he hoped to enter in his own right someday soon, Hawkins offered to join the board of any prospective company, provided that Joel was willing to develop his game on the Apple II. The Apple II had been overshadowed by the likes of the TRS-80 and all those CP/M machines to date, Hawkins admitted, but it was having a very good 1979 and was poised to come on strong in the new decade — poised to be “the computer of the future.” He was, to give credit where it’s due, largely right in this. The Apple II would indeed become the premier gaming computer of the next several years, thanks not least to a standout feature that Hawkins didn’t hesitate to point out to Joel: its color bitmap graphics. If they made their Bismarck game for the Apple II, Joel and John could substitute a color picture of the North Atlantic for textual descriptions of the situation.

Hawkins’s participation should play well with the many Silicon Valley venture capitalists who already knew him as a bright young spark, and he could even get Joel access to Apple’s own distribution network and customer rolls. And, far from being a sacrifice, going with the burgeoning Apple II as the new company’s platform of choice seemed a logical course. Hawkins promised to join the board, and Apple II it was from then on.

Still, Joel remained cautious by nature. All too aware of his own lack of experience, he cast about for a bigger partner to shoulder some of the risk and some of the responsibility. He screwed up his courage to call the home of his self-described “heroes” at the wargaming Mecca of Avalon Hill, and managed to get Thomas N. Shaw — game designer, founding editor of Avalon Hill’s in-house magazine The General, and the most long-serving employee of the company — on the other end of the line. Shaw, in Joel’s words, “blew him off,” said Avalon Hill was already investigating the field of computer gaming for themselves and didn’t particularly need the help of a 21-year-old with no relevant experience, thank you very much. Joel’s next call was to Automated Simulations, a computer-games publisher founded by two veteran tabletop wargamers that struck him as the only publisher remotely close in background and spirit to what he was trying to do. But, flying high on the sales of their proto-CRPG Temple of Apshai, Automated Simulations was more interested in adding to that line than branching out into computer wargames. And, once again, they remained distinctly unimpressed by young Joel himself. If Joel wanted to do this thing, he would have to do it alone.

He had definitively decided at last that he did want to do this thing. At the last possible instant, he obtained a one-year deferral on graduate school and an extension of his summer job at Amdahl to pay the bills while he tried to get his company off the ground. Being a methodical sort who did anything he decided to do thoroughly and conscientiously, Joel, with the assistance of a sympathetic older colleague from Amdahl named David Bowen, prepared an evolving series of business plans over the last five months of 1979, using data drawn from trade journals and a survey he passed out at a local tabletop-gaming convention. They make for fascinating reading today. For instance, one data point had ominous implications for the wargames industry, still sanguine in their expectations of double-digit annual growth in the decade to come, if only anyone there had happened to see it: Joel found from his survey that wargamers who purchased computers immediately saw their expenditures on tabletop games drop by an average of 41 percent.

In one of these documents, Joel shows a remarkable understanding of the nature of experiential gaming and what makes it different and important.

It is believed that users of these games are attempting to create a fantasy world in which they can obtain role identification with heroic figures. This is similar to reading a good book or watching TV, except that in a game it is more interactive, lively, or “hot.” Wargames provide historical realism and heroes with the basic requirements of a good game: elements of skill, strategy, and chance. Typical wargames allow role identification with heroes like General Patton, various admirals, Napoleon, and so on.

The business plans paint a picture of a busy little factory, with a large staff of programmers under Lyon beavering away to turn out games at a rapid clip. For all the plans’ diligence, they don’t evince much understanding of the nature of intellectual property. Under the heading of “Overall Product Strategy,” the final plan unabashedly states that “computerized versions of existing [tabletop] games” will be the company’s early priority, with “computerized wargames designed by a top-flight game designer with a computer in mind from the beginning” coming only later as resources permit. Ah, well… Joel’s company would hardly be the only respected publisher to have a dodgy understanding of intellectual property in the wild and woolly early days of the software industry.

The name of Joel’s venture changed several times. What started out as the placeholder “Company A” became “Computer Simulations,” and only then “Strategic Simulations.” Joel first took to abbreviating the name to “SS,” but the historical connotations of those two letters — especially to wargamers, who tended to be all too steeped in the very era of history in question — were too ugly to let them stand alone. So he settled at last on SSI, for “Strategic Simulations, Incorporated,” an abbreviation with the added bonus of harking back to the tabletop-wargaming institution of SPI. The incorporation in question occurred on December 27, 1979.

Even with Trip Hawkins’s backing, Joel still hadn’t found any venture capitalists willing to take a chance on computerized wargaming by that date. So Joel’s family finally came through to fund his dream, raising some $40,000 in seed capital among themselves. Joel’s big sister Susan quit her job as admitting-and-registration manager at a hospital to run the accounting side of the venture, to serve as office manager, and, just possibly, to keep an eye on her little brother on behalf of the family that had just entrusted him with so much of their money and faith. Susan, who had no particular interest in games or computers, took the job on as a favor and a family obligation. “For the first couple of years, I said I’d stay six months and then leave,” she remembers. “I thought it was a temporary thing.” Instead she would remain throughout SSI’s long run, becoming in her way as integral to the company as Joel himself. This even though she never did much warm to games or computers: “I never felt an affinity for the products. My feelings were for the operation and the people.”

John Lyon finished SSI’s first game in late January of 1980. Still not the slightest bit interested in disguising its origins in the Avalon Hill Bismarck, Joel titled it simply Computer Bismarck. No matter. Computer Bismarck, generally regarded today as the first serious wargame to appear on a microcomputer, made for a very impressive product for those in SSI’s target demographic. Recognizing the need to present a professional appearance — especially in light of Computer Bismarck‘s $60 price tag, four or five times the price of the typical computer game at the time — Joel had taken the unusual step of hiring an artist and packaging designer for SSI right out of the gate. In an industry still dominated by Ziploc baggies stuffed with hand-scrawled photocopied title cards, Computer Bismarck shipped in an actual box sporting Louis Saekow’s ominous head-on graphic of the Bismarck itself. Inside was not only a real, professionally typeset manual but also a generous collection of player aids, including a map and counters for keeping track of those aspects of the strategic situation that the program, even with the aid of the Apple II’s bitmap graphics, couldn’t always show.

Through the auspices of the well-connected Trip Hawkins, Joel made his first significant sale in early February, 50 copies of the game to the Los Altos Computerland. A week later SSI moved out of Joel’s apartment, where by the end there he had been forced to wind his way through a hedge maze built from the first 1000 copies of Computer Bismarck just to reach his bed. After the move, the first of six to ever larger digs that SSI would make over the next decade, Joel hung a map of the United States on the wall. Every time an SSI game sold in a new city, he’d put a pin in the map. Within six weeks, the map was positively bristling with them. Its purpose served, Joel pulled the map off the wall.

They were on their way, but budgets were decidedly tight. That first office space was nothing but a big empty room. Unable to afford cubicles, they made “offices” out of walls of boxes. “When someone grumbled later about not having an office,” Susan remembers, “we’d say the president had a wall of boxes for an office, so you’re in good company.” Despite working for an alleged computer company, Susan managed all of the accounts on paper, with the aid of only “one of those out-of-the-movies adding machines that only does addition and subtraction.” At $15 at the local surplus store, the price had been right.

SSI spent all the money they weren’t spending inside their offices trying to make a good impression outside of them. Determined to advertise Computer Bismarck as something genuinely new under the sun, they came up with a catchy slogan: “The $2160 Wargame!” (The extra $2100, of course, referred to the approximate cost of the Apple II system needed to run it.) Just as Joel had hoped, Computer Bismarck attracted significant attention in traditional wargaming circles, getting big writeups in hardcore magazines like Fire and Movement. Computerized wargames were “here at last,” wrote Joel in his “Designer’s Notes” addendum to that article, “and I suggest you run out and buy a home computer as soon as you can justify it to your wife, girlfriend, or mother.” And at least to some extent his readers apparently did. SSI wound up selling almost 8000 copies of Computer Bismarck. That number may not sound spectacular today, but it wasn’t bad for a niche product in what remained a niche industry. By year’s end Lyon and his team had churned out a few more, slightly less blatantly cloned wargames. SSI’s year-end balance sheet showed a loss of $60,000, but that was hardly unexpected for the first-year startup. They believed they were well on the road to profitability. At the same time, though, Joel was well on the road to overhauling the way that SSI did business.

What caused him to rethink himself was an unsolicited and thoroughly unexpected package that arrived within months of the release of Computer Bismarck. In the package was a game from an Arkansan named Dan Bunten, [1]Dan Bunten later became Danielle Bunten Berry, and lived until her death in 1998 under that name. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. a football simulation that used the Apple II’s optional paddle controllers to brilliant effect. Bunten wanted to know if SSI would be interested in publishing it. Hard as it may be to believe, this was a business model that had never occurred to Joel. Instead of killing themselves to design and program all these games in-house, SSI could curate games from outside developers — handle the packaging and marketing while leaving the tough, unpredictable creative effort to others. If Joel needed any further convincing, the fact that Bunten’s slick football game made SSI’s in-house games look rather workmanlike provided plenty. SSI published Computer Quarterback in September of 1980 as their first non-in-house-developed game. It promptly became by far the fastest seller in their catalog, just in case Joel needed yet further convincing.

SSI’s year-end 1980 “business plan,” really a state-of-the-business report, incorporates an important change from the original plan: “SSI is now relying on outside designers to provide roughly half of all new products.” That percentage would only increase in the years to come. Joel’s original vision of SSI as a sort of wargames factory, with a small army of programmers beavering away to churn out games, would never materialize. No big loss. This new way worked so much better.

As the existence of Computer Quarterback will attest, SSI’s games almost immediately began to depart from the most literal definition of a wargame. Within a few years they would add to their growing military-history library not only more sports games, but also economic simulations, political challenges, and science-fictional scenarios. Somewhat to the chagrin of Joel, a hardcore military wargamer first and last, the average non-military game actually sold much better than the average military; the biggest sellers of all in SSI’s first few years were Computer Quarterback and Computer Baseball.

Yet, like the games of most publishers carving out an identity in the young industry, SSI’s games did all tend to share a personality. In an earlier article, I described that personality as “almost aggressively off-putting.” While not the kindest description I’ve ever written, I think it holds true to the way the average non-wargamer perceived them. It’s right there in the name of the company that made them. These games were very eager to brand themselves as thinking people’s strategic simulations rather than mere games. Rather than minimizing complexities, they reveled in them — that’s to say, they reveled in as many complexities as it was actually possible to generate on a 48 K Apple II. Like the tabletop wargames that inspired them, mechanical elegance, interface, and aesthetics all took a back seat to the idea of recreating history. It may sound like stereotyping to say that most of SSI’s games were written by serious-minded bearded men in home offices whose walls were lined with military-history books… but, well, most of SSI’s games were written by serious-minded bearded men in home offices whose walls were lined with military-history books. Long after the rest of the industry had sworn off BASIC for high-performance machine language, SSI continued to happily accept and publish games written in pure BASIC, hundreds of lines of amateurish spaghetti code. For the SSI hardcore, who like tabletop wargamers loved to explore and tinker with rules in the name of historical accuracy or what-if scenarios, the use of easily listable and modifiable BASIC was as much plus as minus. The great Sid Meier gave us the maxim that “fun trumps realism” in game design. One might say that SSI’s games took the opposite position. But, almost paradoxically, for the niche of people on their wavelength the realism — or the abstract idea of realism, whatever the actual reality of simulation on a 48 K Apple II — was the fun.

For everyone else, the appeal of these baroque, balky, bulky creations remained a mystery. The shops often didn’t know quite what to do with them. Here’s Ed Thomas, a former manager of Software Etc.’s showcase store in Manhattan:

The boxes were half again as big as any other box on the shelf, and they were these intricate wargames with names like Beachhead: Moscow, 1944. I hated those boxes. The only way to display them was to put them on the top shelf, which messed up the order I was trying to establish. In addition, the covers weren’t very attractive, and I never had enough of any one title to face-out the boxes. These damned over-sized, ugly boxes were not at all worth the trouble they caused. I took an immediate dislike to the company that was giving me such a hard time.

That was my first encounter with Strategic Simulations, Inc., a company filled, I was sure, with people who, when not writing intricate computer code, were in a military-style war room recreating D-Day.

SSI proved uniquely impervious to the depredations of the software pirates who were causing so much outrage elsewhere in the industry. Their fool-proof method of copy protection didn’t involve mismatched sector numbers or manual-lookup schemes. It was rather the simple fact that few of the people who copied and traded games had any interest in those of SSI. The piracy scene just couldn’t be bothered, unless it was to have an occasional game to mock for its ugly graphics, its slowness, and its sheer BASICness.

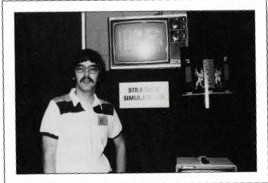

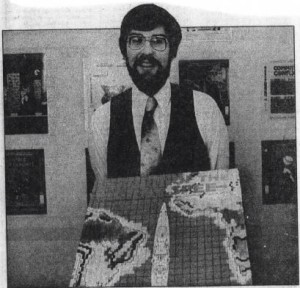

Joel poses in 1982 with Pursuit of the Graf Spee, the only SSI game he designed and programmed himself — albeit only by cribbing liberally from Computer Bismarck. It sold just 2082 units.

The niche audience for SSI’s games — niche even by the standards of the still tiny software industry in general — sharply limited the potential sales of each of them. As Joel himself put it in 1982, “I’m just a niche in a subset.” And then there were so many sub-niches within SSI’s niche: a dedicated sports gamer raised on Strat-O-Matic Football might not care about military titles at all, a World War II buff might not have any interest in American Civil War games. Relying on the fact that many of the dedicated hardcore would buy lots of games within the sub-niche that did appeal to them, SSI made it up in the sheer volume of titles they published. They really were astoundingly prolific. Already in that 1980 business plan they are planning to leverage all those outside designers to release a new game for every month of 1981. Shockingly, they pulled it off, and kept right on flooding the market with titles thereafter.

In the first four years of SSI’s existence, they released no fewer than 43 separate games, not counting ports and enhanced editions. Most of these never came close to cracking five digits in total unit sales. Some barely sold 2000 copies. Precisely three of them cracked 20,000 units, with the most successful of them all, Computer Baseball, a real outlier at over 45,000 copies sold. Titles like that presumably broke through to some extent beyond the SSI hardcore. But mostly SSI relied on the fanatically loyal customers who bought lots of their games and quite possibly no games at all from anyone else. With virtually none of their games selling in enough quantities to meet even the most generous definition of a hit, their ever expanding back catalog was everything. Each SSI game, even those that initially struggled to sell 1000 units, remained available for years. It would, for instance, still be possible to buy a brand new copy of good old Computer Bismarck in 1986 — and still for a full $60 at that.

It was a comfortable niche as niches go, but there was only room for one company there. About six months after Computer Bismarck, Avalon Hill, as Tom Shaw had once told Joel they would, started their own line of computerized wargames. That, combined with the existence of Computer Bismarck, was a recipe for trouble. Sure enough, Avalon Hill was soon marketing computerized versions of some of their other tabletop classics using the same prefix: Computer Diplomacy, Computer Football Strategy, Computer Circus Maximus. Just to aggravate the confusion, Avalon Hill coincidentally released a second edition of the tabletop Bismarck, which had been out of print for a number of years, the very same year as Computer Bismarck. With the two companies in direct competition, a call from the lawyers was inevitable. SSI got off relatively easy: sued for trademark and copyright infringement in 1984, they settled by agreeing to pay Avalon Hill a lump sum of $30,000 and a 5 percent royalty on future sales — which, given that Computer Bismarck was by then almost five years old and creakily archaic, were likely to be modest at best even for the back-catalog-driven SSI.

All told, Avalon Hill plugged away at the computer thing for a good five years, but despite the drawing power of their name among tabletop veterans could never quite catch up to SSI in either sales or wargamer respect, could never quite get their computer division to turn a real profit. Part of the problem was doubtless that their games, being programmed by a rather unimaginative in-house team, were “really simple,” as Joel puts it, in comparison to SSI’s — not a good thing to players that craved the validation of complexity. And part of their problem was doubtless just the disadvantages of being second. SSI already owned this market. Stymieing the giant that had once blown him off had to bring a smile of vindication even to the mild-mannered face of Joel Billings.

Less happily for SSI, other markets had owners as well. When SSI tried to branch out from their slow, cerebral signature games it just didn’t work for them. In 1982, they launched a line they called RapidFire, consisting of faster-paced, more graphically impressive games, generally programmed and released first on the more audiovisually capable Atari 8-bit line rather than the Apple II. Among the RapidFire games was Dan Bunten’s pioneering proto-real-time-strategy game Cytron Masters. But sales weren’t notably better than their typical wargame: Cytron Masters sold just 4702 units. And as competition heated up it became difficult for little SSI to retain developers who didn’t work firmly in the company’s own niche. Dan Bunten, for instance, was lured away by Trip Hawkins’s new Electronic Arts shortly after finishing Cytron Masters. SSI soon returned to focusing exclusively on the types of games with which Joel was most comfortable.

They did have one valuable ally in their corner in the increasingly competitive industry. In 1981, a Baptist minister and veteran tabletop gamer named Russell Sipe contacted Joel to ask his opinion on a potential magazine that would exclusively cover computer games, focusing on those of an intellectual, wargamey bent. Recognizing a kindred spirit immediately, Joel was very supportive, even committing his own still fragile venture to buying extensive advertising in the new publication. Computer Gaming World became so associated with SSI in its early years that one might be excused if one took it for SSI’s own publication. The slim first issue, for example, includes an extended feature-length review of SSI’s new Torpedo Fire; a review of, playing tips for, and an after-action report from SSI’s President Elect; and a “greatest baseball team of all time” tournament conducted using SSI’s Computer Baseball. This de facto partnership, born like most things involving SSI of shared interests and genuine affection rather than guile, served SSI well for many years, helping to get their niche games in front of just the right niche of potential buyers. SSI grew cautiously but healthily year by year, from sales of $317,000 in 1980 to over $3 million in 1984. The employee rolls grew to match, from 11 at the end of 1980 to 32 at the end of 1984.

While the vast majority of the games were provided by outside developers (the aforementioned serious-minded bearded men), just packaging and coming up with manuals and other supporting materials for a new game every single month was a herculean task, especially given that SSI generally did a very good job with such things; these were expensive games, and they needed to look it. In lieu of the army of programmers — SSI’s in-house development group, while never entirely eliminated, remained much smaller than originally planned — an army (or at any rate a small brigade) of other personnel came on board to design the packaging, write the manuals, ship the games, and deal with all the other logistics of running a growing business. Some of these folks were, like Joel, hardcore gamers delighted to be spending their days in what Joel’s eventual wife came to call “a treehouse for wargamers.” For the rest, the folks like Susan Billings, it was just a job, but a pretty great job all the same. Joel, apart from his one eccentric habit of wearing a three-piece suit to work every day, was as easygoing, down-to-earth, and reasonable a boss as anyone could ever wish for. But it was at least as much Susan who set the tone of the workplace while Joel was hopelessly lost inside his wargames: “It was the opportunity to try to create the perfect work environment so people would want to come to work. It was the chance of a lifetime to develop a company using your style, based on your style, and doing it with someone from your family.” So, yes, SSI was a very happy place — as happy in its way as the legendarily happy Infocom, and for a much longer stretch of time.

SSI employees Tena Lawry and Connie Barron boogie down as the “Simulated Bunnies” because… well, just because.

Tena Lawry, who would later become SSI’s senior purchaser, joined in 1981 as a temporary disk copier, responsible for shoving disks into drives and then dropping them into boxes all day long. (If you could put toast in a toaster, you were qualified, says Tena wryly.) Tena:

We broke for lunch and Joel walked in with five pizzas. We all sat on the floor munching away and an announcement was made that we were going to have a rousing game of Nuclear War [a Flying Buffalo game]. Now I’m nervous. I figured we were going to play some intense videogame. I hadn’t even mastered Pac-Man yet, so this would be interesting.

Nuclear War turned out to be a card game in which you amass missiles and such and then trump your opponent in an attempt to annihilate his population. At one point, I dropped a major nuclear payload on Joel. I thought at this point that this may not have been the politically correct thing to do. After all, Joel was the president of SSI and I had just wiped out his entire population. But I soon found out that Joel always appreciates a good game strategist even if it means a pile of dead-body cards.

That night at dinner my family asked me what I had done on my first day at SSI. I said I copied disks, assembled games, and obliterated an entire population while eating pizza. Silence fell over the table. “Just kidding,” I said.

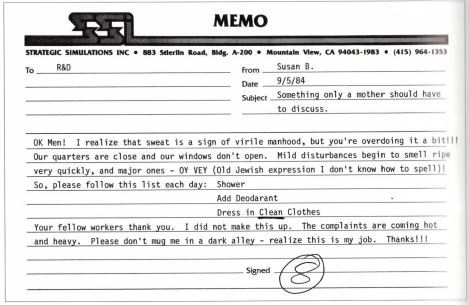

It fell to Susan Billings to address a delicate problem when SSI’s technical staff — hackers being hackers — started to spend much too long in front of their computers between hygiene breaks. She handled the situation with humor, grace, and aplomb, as she did most situations at SSI. Old timers laugh about the infamous “B.O. Memo” to this day.

At the time that Susan was writing that memo, SSI was tentatively trying to branch out again into a new genre. Thankfully, this expansion would be more successful than the RapidFire line had been. Indeed, in the fullness of time it would lead to a transformative deal with the titan of the other side of the tabletop industry, the yin to Avalon Hill’s yang. We’ll step back next time to look at what set that titan on a collision course with Joel Billings’s modest little treehouse for wargamers.

(Sources: This article is largely drawn from the collection of documents that Joel Billings donated to the Strong Museum of Play, which includes lots of internal SSI documents and some press clippings. Also, Matt Barton’s YouTube interviews with Billings.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Dan Bunten later became Danielle Bunten Berry, and lived until her death in 1998 under that name. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |

|---|