Zork Zero the idea was kicking around Infocom for quite a long time before Zork Zero the game was finally realized. Steve Meretzky first proposed making a prequel to the original Zork trilogy as far back as 1985, when he included it on a list of possible next games that he might write after finishing his personal passion project of A Mind Forever Voyaging. The Zork Zero he described at that time not only already had the name but the vast majority of the concept of the eventual finished game as well.

As the name implies, a prequel to the Zork trilogy. It would be set in the Great Underground Empire, and covering a long period of time, from the end of the reign of Dimwit Flathead in 789 through the fall of the GUE in 883, and possibly through 948 (the year of the Zork trilogy). It would almost certainly end “west of a white house.” There would be some story, probably about as much as Enchanter or Sorcerer. For the most part, though, it would be an intensely puzzle-oriented game with a huge geography.

The fact that Meretzky knew in what years Dimwit Flathead died, the Great Underground Empire fell, and Zork I began says much about his role as the unofficial keeper of Zorkian lore at Infocom. He had already filled a huge notebook with similarly nitpicky legends and lore. This endeavor was viewed by most of the other Imps, who thought of the likes of Dimwit Flathead as no more than spur-of-the-moment jokes, with bemused and gently mocking disinterest. Still, if Infocom was going to do a big, at least semi-earnest Zork game, his obsessiveness about the milieu made Meretzky the obvious candidate for the job.

But that big Zork game didn’t get made in 1985, partly because the other Imps remained very reluctant to sacrifice any real or perceived artistic credibility by trading on the old name and partly because the same list of possible next projects included a little something called Leather Goddesses of Phobos that everyone, from the Imps to the marketers to the businesspeople, absolutely loved. Brian Moriarty’s reaction was typical: “If you don’t do this, I will. But not as well as you could.”

After Meretzky completed Leather Goddesses the following year, Zork Zero turned up again on his next list of possible next projects. This time it was granted more serious consideration; Infocom’s clear and pressing need for hits by that point had done much to diminish the Imps’ artistic fickleness. At the same time, though, Brian Moriarty also was shopping a pretty good proposal for a Zork game, one that would include elements of the CRPGs that seemed to be replacing adventure games in some players’ hearts. Meanwhile Meretzky’s own list included something called Stationfall, the long-awaited sequel to one of the most beloved games in Infocom’s back catalog. While Moriarty seemed perfectly capable of pulling off a perfectly acceptable Zork, the universe of Planetfall, and particularly the lovable little robot Floyd, were obviously Meretzky’s babies and Meretzky’s alone. Given Infocom’s commercial plight, management’s choice between reviving two classic titles or just one was really no choice at all. Meretzky did Stationfall, and Moriarty did Beyond Zork — with, it should be noted, the invaluable assistance of Meretzky’s oft-mocked book of Zorkian lore.

And then it was 1987, Stationfall too was finished, and there was Zork Zero on yet another list of possible next projects. I’ll be honest in stating that plenty of the other project possibilities found on the 1987 list, some of which had been appearing on these lists as long as Zork Zero, sound much more interesting to this writer. There was, for instance, Superhero League of America, an idea for a comedic superhero game with “possible RPG elements” that would years later be dusted off by Meretzky to become the delightful Legend Entertainment release Superhero League of Hoboken. There was a serious historical epic taking place on the Titanic that begs to be described as Meretzky’s Trinity. And there was something with the working title of The Best of Stevo, a collection of interactive vignettes in the form if not the style of Nord and Bert Couldn’t Make Head or Tail of It.

Mind you, not all of the other projects were winners. A heavy-handed satire to be called The Interactive Bible, described by Meretzky as “part of my ongoing attempt to offend every person in the universe,” was eloquently and justifiably lacerated by Moriarty.

As you noted, this game is likely to offend many people, and not just frothing nutcakes either. A surprising number of reasonable people regard the Book with reverence. They are likely to regard your send-up as superficial and juvenile. They will wonder what qualifies you to poke fun at their (or anybody’s) faith. Why do you want to write this? Do you really think it will sell?

If Zork Zero wasn’t at the bottom of anyone’s list like The Interactive Bible, no one was exactly burning with passion to make it either. Few found the idea of going back to the well of Zork yet again all that interesting in creative terms, especially as Beyond Zork was itself still very much an ongoing project some weeks from release. The idea’s trump card, however, was the unique commercial appeal most still believed the Zork trademark to possess. Jon Palace’s faint praise was typical: “I’m sure this would sell very well. It’s certainly ‘safe.'” By 1987, the commercially safe route was increasingly being seen as the only viable route within Infocom, at least until they could manage to scare up a few hits. A final tally revealed that Zork Zero had scored an average of 7.2 among “next Meretzky project” voters on a scale of 1 to 10, edging out Superhero League of America by one tenth of a point, Titanic by two tenths, and The Best of Stevo by one full point; the last was very well-liked in the abstract, but its standing was damaged by the fact that, unusually for Meretzky, the exact form the vignettes would take wasn’t very well specified.

On August 7, 1987, it was decided provisionally to have Meretzky do Zork Zero next. In a demonstration of how tepid everyone’s enthusiasm remained for such a safe, unchallenging game, an addendum was included with the announcement: “I think it is fair to add that if Steve happens to have a flash of creativity in the next few days and thinks of some more ideas for his experimental story project (Best of Stevo), nearly everyone in this group would prefer that he do that product.” That flash apparently didn’t come; The Best of Stevo was never heard of again. Also forgotten in the rush to do Zork Zero was the idea, mooted in Beyond Zork, of Zork becoming a series of CRPG/text-adventure hybrids, with the player able to import the same character into each successive game. Zork Zero would instead be a simple standalone text adventure again.

While it’s doubtful whether many at Infocom ever warmed all that much to Zork Zero as a creative exercise, the cavalcade of commercial disappointments that was 1987 tempted many to see it as the latest and greatest of their Great White Hopes for a return to the bestseller charts. It was thus decided that it should become the first game to use Infocom’s new version 6 Z-Machine, usually called “YZIP” internally. Running on Macintosh II microcomputers rather than the faithful old DEC, the YZIP system would at last support proper bitmap illustrations and other graphics, along with support for mice, sound and music, far more flexible screen layouts, and yet bigger stories over even what the EZIP system (known publicly as Interactive Fiction Plus) had offered. With YZIP still in the early stages of development, Meretzky would first write Zork Zero the old way, on the DEC. Then, when YZIP was ready, the source code could be moved over and the new graphical bells and whistles added; the new version of ZIL was designed to be source-compatible with the old. In the meantime, Stu Galley was working on a ground-up rewrite of the parser, which was itself written in ZIL. At some magic moment, the three pieces would all come together, and just like that Infocom would be reborn with pictures and a friendlier parser and lots of other goodies, all attached to the legendary Zork name and written by Infocom’s most popular and recognizable author. That, anyway, was the theory.

Being at the confluence of so much that was new and different, Zork Zero became one of the more tortured projects in Infocom’s history, almost up there with the legendarily tortured Bureaucracy project. None of the problems, however, were down to Meretzky. Working quickly and efficiently as always, his progress on the core of the game proper far outstripped the technology enabling most of the ancillary bells and whistles. While Stu Galley’s new parser went in on November 1, 1987, it wasn’t until the following May 10 that a YZIP Zork Zero was compiled for the first time.

In sourcing graphics for Zork Zero, Infocom was on completely foreign territory. Following the lead of much of the computer-game industry, all of the graphics were to be created on Amigas, whose Deluxe Paint application was so much better than anything available on any other platform that plenty of artists simply refused to use anything else. Jon Palace found Jim Shook, the artist who would do most of the illustrations for Zork Zero, at a local Amiga users-group meeting. Reading some of the memos and meeting notes from this period, it’s hard to avoid the impression that — being painfully blunt here — nobody at Infocom entirely knew what they were doing when it came to graphics. As of February of 1988, they still hadn’t even figured out what resolution Shook should be working in. “We still don’t know whether images should be drawn in low-res, medium-res, interlace, or high-res mode on the Amiga in Deluxe Paint,” wrote Palace plaintively in one memo. “Joel claims Tim should know. Tim, do you know?”

Infocom wound up turning to Magnetic Scrolls, who had been putting pictures into their own text adventures for quite some time, for information on “graphics compression techniques,” a move that couldn’t have sat very well with such a proud group of programmers. The graphics would continue to be a constant time sink and headache for many months to come. Steve Meretzky told me that he remembers the development of Zork Zero primarily as “heinous endless futzing with the graphics, mostly on an Amiga, to make them work with all the different screen resolutions, number of colors, pixel aspect ratios, etc. In my memory, it feels like I spent way more time doing that than actually designing puzzles or writing ZIL code.”

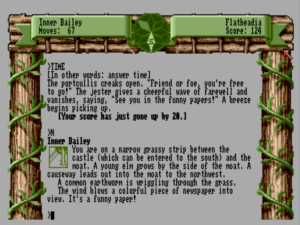

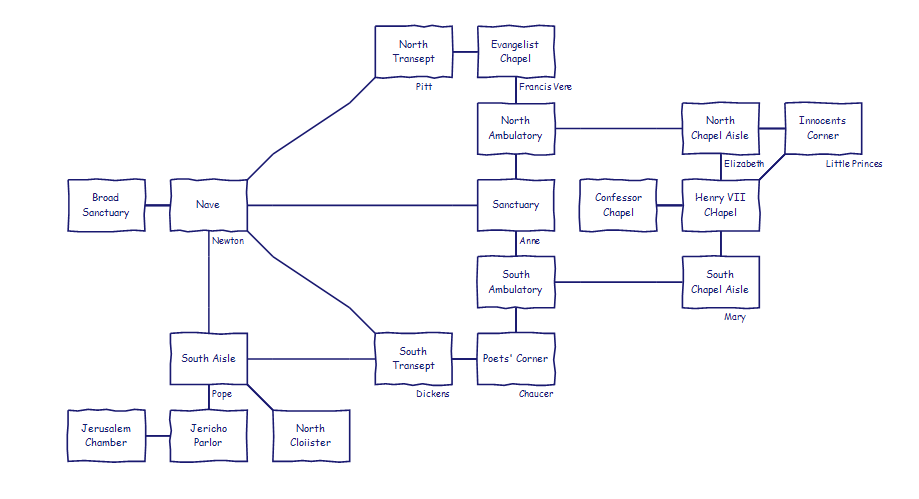

Zork Zero uses graphics more often to present the look of an illuminated manuscript than for traditional illustrations.

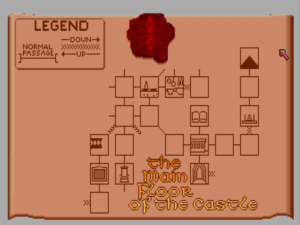

And yet in comparison to games like those of Magnetic Scrolls, the finished Zork Zero really wouldn’t have a lot of graphics. Instead of an illustration for each room, the graphics take the form of decorative borders, an illuminated onscreen map, some graphical puzzles (solvable using a mouse), and only a few illustrations for illustrations’ sake. Infocom would advertise that they wanted to use graphics in “a new way” for Zork Zero — read, more thoughtfully, giving them some actual purpose rather than just using them for atmosphere. All of which is fair enough, but one suspects that money was a factor as well; memos from the period show Infocom nickel-and-diming the whole process, fretting over artist fees of a handful of thousand dollars that a healthier developer wouldn’t have thought twice about.

The financial squeeze also spelled the end of Infocom’s hopes for a full soundtrack, to have been composed by Russell Lieblich at Mediagenic, who had earlier done the sound effects for The Lurking Horror and Sherlock: The Riddle of the Crown Jewels. But the music never happened; when Zork Zero finally shipped, it would be entirely silent apart from a warning beep here or an acknowledging bloop there.

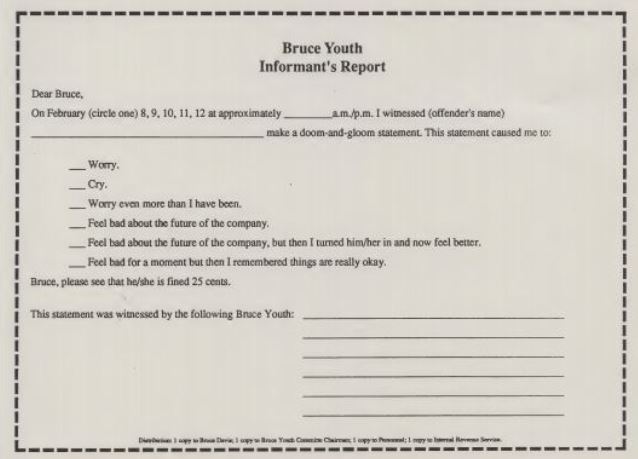

Hemorrhaging personnel as they were by this point, Infocom found themselves in a mad scramble to get all the pieces that did wind up making it into Zork Zero together in time for Christmas 1988, months after they had originally hoped to ship the game. Bruce Davis grew ever more frustrated and irate at the delays; a contemporary memo calls him a “looming personality” and notes how he is forever “threatening a tantrum.” A desperate-sounding “Proclamation” went out to the rank-and-file around the same time: “The one who can fix the bugs of Zork Zero, and save the schedule from destruction, shall be rewarded with half the wealth of the Empire.” Signed: “Wurb Flathead, King of Quendor.”

Like a number of Zork Zero‘s illustrations, this one actually conveys some important information about the state of the game rather than being only for show.

Time constraints, the fact that the beta builds ran only on the Macintosh, and Infocom’s determination to test Zork Zero primarily using new testers unfamiliar with interactive fiction meant that it didn’t receive anywhere near the quantity or quality of outside feedback that had long been customary for their games. Many of the new testers seemed bemused if not confused by the experience, and few came anywhere close to finishing the game. I fancy that one can feel the relative lack of external feedback in the end result, as one can the loss of key voices from within Infocom like longtime producer Jon Palace and senior tester Liz Cyr-Jones.

Despite the corner-cutting, Infocom largely missed even the revised target of Christmas 1988. Only the Macintosh version shipped in time for the holiday buying season, the huge job of porting the complicated new YZIP interpreter to other platforms having barely begun by that time. Zork Zero was quite well-received by the Macintosh magazines, but that platform was far from the commercial sweet spot in gaming.

A sort of cognitive dissonance was a thoroughgoing theme of the Zork Zero project from beginning to end. It’s right there in marketing’s core pitch: “Zork Zero is the beginning of something old (the Zork trilogy) and something new (new format with graphics).” Unable to decide whether commercial success lay in looking forward or looking back, Infocom tried to have it both ways. Zork Zero‘s “target audience,” declared marketing, would be “primarily those who are not Infocom fans; either they have never tried interactive fiction or they have lost interest in Infocom.” The game would appeal to them thanks to “a mouse interface (enabling the player to move via compass rose), onscreen hints, a new parser (to help novices), and pretty pictures that will knock your socks off!”

Yet all the gilding around the edges couldn’t obscure the fact that Zork Zero was at heart the most old-school game Infocom had made since… well, since Zork I really. That, anyway, was the last game they had made that was so blatantly a treasure hunt and nothing more. Zork Zero‘s dynamic dozen-turn introduction lays out the reasons behind the static treasure hunt that will absorb the next several thousand turns. To thwart a 94-year-old curse that threatens to bring ruin to the Great Underground Empire, you must assemble 24 heirlooms that once belonged to 12 members of the Flathead dynasty and drop them in a cauldron. Zork Zero is, it must be emphasized, a big game, far bigger than any other that Infocom ever released, its sprawling geography of more than 200 rooms — more than 2200 if you count a certain building of 400 (nearly) identical floors — housing scores of individual puzzles. The obvious point of comparison is not so much Infocom’s Zork trilogy as the original original Zork, the one put together by a bunch of hackers at MIT in response to the original Adventure back in the late 1970s, long before Infocom was so much as a gleam in anyone’s eye.

The question — the answer to which must always to some extent be idiosyncratic to each player — is whether Zork Zero works for you on those terms. In my case, it doesn’t. The PDP-10 Zork is confusing and obscure and often deeply unfair, but it carries with it a certain joyous sense of possibility, of the discovery of a whole new creative medium, that we can enjoy vicariously with its creators. Zork Zero perhaps also echoes the emotional circumstances of its creation: it just feels tired, and often cranky and mean-spirited to boot. Having agreed to make a huge game full of lots of puzzles, Meretzky dutifully provides, but the old magic is conspicuously absent.

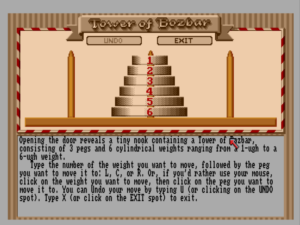

Infocom always kept a library of puzzly resources around the office to inspire the Imps: books of paradoxes and mathematical conundrums, back issues of Games magazine, physical toys and puzzles of all descriptions. But for the first time with Zork Zero, Meretzky seems not so much inspired by these resources as simply cribbing from them. Lots of the puzzles in Zork Zero are slavish re-creations of the classics: riddles, a Tower of Hanoi puzzle, a peg game. Even the old chestnut about the river, the fox, the chicken, and the sack of grain makes an appearance. And even some of the better bits, like a pair of objects that let you teleport from the location of one to that of another, are derivative of older, better Infocom games like Starcross and Spellbreaker. One other, more hidden influence on Zork Zero‘s everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach to puzzle design — particularly on the occasional graphical puzzles — is likely Cliff Johnson’s puzzling classic The Fool’s Errand, which Meretzky was playing with some dedication at the very time he was designing his own latest game. The Fool’s Errand‘s puzzles, however, are both more compelling and more original than Zork Zero‘s. Meretzky’s later Hodj ‘n’ Podj would prove a far more worthy tribute.

Zork Zero is a difficult game, and too often difficult in ways that really aren’t that much fun. I’m a fan of big, complicated puzzlefests in the abstract, but Zork Zero‘s approach to the form doesn’t thrill me. After the brief introductory sequence, the game exposes almost the whole of its immense geography to you almost immediately; there’s nothing for it but to start wandering and trying to solve puzzles. The combinatorial explosion is enormous. And even when you begin to solve some of the puzzles, the process can be made weirdly unsatisfying by the treasure-hunt structure. Too much of the time, making what at first feels like a significant step forward only yields another object to throw into the cauldron for some more points. You know intellectually that you’re making progress, but it doesn’t really feel like it.

I much prefer the approach of later huge puzzlefests like Curses! and The Mulldoon Legacy, which start you in a constrained space and gradually expand in scope as you solve puzzles. By limiting their initial scope, these games ease you into their worlds and limit the sense of hopeless aimlessness that Zork Zero inspires, while a new set of rooms to explore provides a far more tangible and satisfying reward for solving a puzzle sequence than does another object chunked in the cauldron and another few points. The later games feel holistically designed, Zork Zero like something that was just added to until the author ran out of space. Even The Fool’s Errand restricts you to a handful of puzzles at the beginning, unfolding its mysteries and its grand interconnections only gradually as you burrow ever deeper. That Infocom of all people — Steve Meretzky of all people, whose Leather Goddesses of Phobos and Stationfall are some of the most airtight designs in Infocom’s catalog — is suddenly embracing the design aesthetic of the 1970s is downright weird for a game that was supposed to herald a bright new future of more playable and player-friendly interactive fiction.

The in-game Encyclopedia Frobozzica is a nice but rather underused feature. The encyclopedia could have provided more nudges for some more of the more obscure puzzles and maybe even some direction as to what to be working on next. Instead that work is all shuffled off to the hint menu, the use of which feels like giving up or even cheating.

The puzzles rely on the feelies more extensively than any other Infocom game, often requiring you to make connections with seemingly tossed-off anecdotes buried deep within “The Flathead Calendar.” I generally don’t mind this sort of thing overmuch, but, like so much else in Zork Zero, it feels overdone here. These puzzles feel like they have far more to do with copy protection than the player’s enjoyment — but then much of the time Zork Zero seems very little concerned with the player’s enjoyment.

I love the headline of the single review of Zork Zero that’s to be found as of this writing on The Interactive Fiction Database: “Enough is enough!” That’s my own feeling when trying to get through this exhausting slog of a game. As if the sheer scope and aimlessness of the thing don’t frustrate enough, Meretzky actively goes out of his way to annoy you. There is, for instance, a magic wand with barely enough charges in it; waste a few charges in experimentation, and, boom, you’re locked out of victory. There’s that aforementioned building of 400 floors, all but one of them empty, which the diligent player will nevertheless feel the need to explore floor by floor, just in case there’s something else there; this is, after all, just the type of game to hide something essential on,say, floor 383. And then there’s the most annoying character in an Infocom game this side of Zork I‘s thief, a jester who teleports in every few dozen turns to do some random thing to you, like stick a clown nose over your own (you have to take it off within a certain number of turns or you’ll suffocate) or turn you into an alligator (you have to waste a few turns getting yourself turned back, then deal with picking up all of your possessions off the ground, putting those things you were wearing back on, etc.). Some of these gags are amusing the first time they happen, but they wear out their welcome quickly when they just keep wasting your time over a game that will already require thousands of moves to finish. The jester’s worst trick of all is to teleport you somewhere else in the game’s sprawling geography; you can be hopelessly trapped, locked out of victory through absolutely no fault of your own, if you’re unlucky and don’t have the right transportation handy. Hilariously, Infocom’s marketing people, looking always for an angle, hit upon selling the jester as Meretzky’s latest lovable sidekick, “every bit as enjoyable and memorable as Floyd of Planetfall fame.” Meretzky himself walked them back from that idea.

Some of the puzzles, probably even most of them, are fine enough in themselves, but there is a sprinkling of questionable ones, and all are made immeasurably more difficult by the fact that trying out a burst of inspiration can absorb 50 moves simply transiting from one side of the world to the other. Throw in a sharply limited inventory, which means you might need to make three or four round trips just to try out all the possible solutions you can think of, and things get even more fun. Graham Nelson among others has made much of the idea that the 128 K limitation of the original Z-Machine was actually a hidden benefit, forcing authors to hone their creations down to only what needed to be there and nothing that didn’t. I’ve generally been a little skeptical of that position; there are any number of good Infocom games that feel like they might have been still a little better with just a little more room to breathe. Zork Zero, however, makes as compelling a case as one can imagine for the idea that less is often more in interactive fiction, that constraints can lead to better designs.

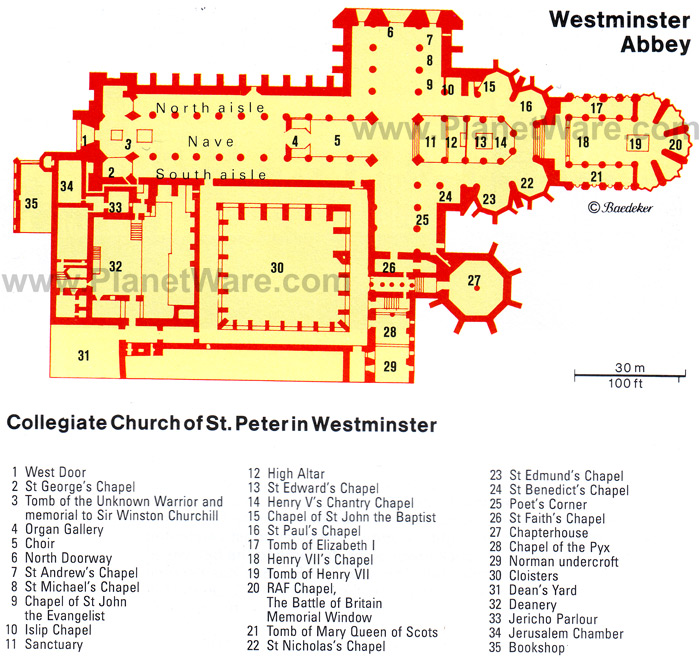

The in-game mapping is handy from time to time, but, split into many different regions and viewable only by typing “MAP” from the main screen as it is, is not really ideal. A serious player is likely to be back to pencil and paper (or, these days, Trizbort) pretty quickly.

Which is actually not to say that Meretzky was operating totally unfettered by space constraints. While the YZIP format theoretically allowed a story size of up to 512 K not including graphics, the limitations of Infocom’s least-common-denominator platform, the Apple II, meant that the practical limit was around 340 K, a fairly modest expansion on the old 256 K EZIP and XZIP formats used for the Interactive Fiction Plus line. But still more restrictive was the limitation on the size of what Infocom called the “pre-load,” that part of the story data that could change as the player played, and that thus needed to always be in the host machine’s memory. The pre-load had to be held under about 55 K. Undoubtedly due in part to these restrictions, Zork Zero clearly sacrifices depth for breadth in comparison to many Infocom games that preceded it. The “examine” command suffers badly, some of the responses coming off like oxymorons: “totally ordinary looking writhing mass of snakes”; “totally ordinary looking herd of unicorns.” The sketchy implementation only adds to the throwback feel of the game as a whole.

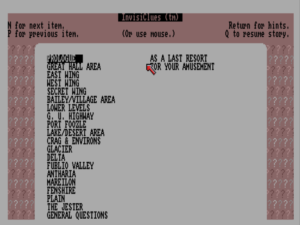

The hints are certainly nice to have given the complexity and scope of the game, but they unfortunately aren’t context-sensitive. It’s all too easy to accidentally read the wrong one when trying to sort through this jumble.

Another subtle hidden enemy of Zork Zero as a design is the online hint system. Installed with the best of intentions in this as well as a few earlier Infocom games, it could easily lead to creeping laziness on the part of a game’s Implementor. “If the player really gets stuck, she can always turn to the hints,” ran the logic — thus no need to fret to quite the same extent over issues of solubility. The problem with that logic is that no one likes to turn to hints, whether found in the game itself, in a separate InvisiClues booklet, or in an online walkthrough. People play games like Zork Zero to solve them themselves, and the presence of a single bad puzzle remains ruinous to their experience as a whole even if they can look up the answer in the game itself. Infocom’s claim that “the onscreen hints help you through the rough spots without spoiling the story” doesn’t hold much water when one considers that Zork Zero doesn’t really have any story to speak of.

More puzzling is the impact — or rather lack thereof — of Stu Galley’s much-vaunted new parser. Despite being a ground-up rewrite using “an ATN algorithm with an LALR grammar and one-token look-ahead,” whatever that means, it doesn’t feel qualitatively different from those found in earlier Infocom games. The only obvious addition is the alleged ability to notice when you’re having trouble getting your commands across, and to start offering sample commands and other suggestions. A nice idea in theory, but the parser mostly seems to decide to become helpful and start pestering you with questions when you’re typing random possible answers to one of the game’s inane riddles. Like your racist uncle who decides to help you clean up after regaling you with his anecdotes over the Thanksgiving dinner table, even when Zork Zero tries to be helpful it’s annoying. Nowhere is the cognitive dissonance of Zork Zero more plainly highlighted than in the juxtaposition of this overly helpful, newbie-friendly parser with the old-school player hostility of the actual game design. “Zork hates its player,” wrote Robb Sherwin once of the game that made Infocom. After spending years evolving interactive fiction into something more positive and interesting than that old-school player hostility, Infocom incomprehensibly decided to circle back to how it all began with Zork Zero.

The most rewarding moment comes right at the end — and no, not because you’re finally done with the thing, although that’s certainly a factor too. In the end, you wind up right where it all began for Zork and for Infocom, before the famous white house, about to assume the role of the Dungeon Master, the antagonist of the original trilogy. There’s a melancholy resonance to the ending given the history not just of the Great Underground Empire but of Infocom in our own world. Released on July 14, 1989, the MS-DOS version of Zork Zero — the version that most of its few buyers would opt for — was one of the last two Infocom games to ship. So, the very end for Infocom circles back to the very beginning in many ways. Whether getting there is worth the trouble is of course another question.

As the belated date of the MS-DOS release will attest, versions of Zork Zero for the more important game-playing platforms were very slow in coming. The Amiga version didn’t ship until March of 1989, the Apple II version in June, followed finally by that MS-DOS version — the most important of all, oddly left for last. By that time Bruce Davis had lost patience, and Infocom had ceased to exist as anything other than a Mediagenic brand. The story of Zork Zero‘s failure to save Infocom thus isn’t so much the story of its commercial failure — although, make no mistake, it was a commercial failure — as the story of Infocom’s failure to just get the thing finished in time to even give it a chance of making a difference. Already an orphaned afterthought by the time it appeared on the platform that mattered most, Zork Zero likely never managed to sell even 10,000 copies in total. So much for Infocom’s “new look, new challenge, new beginning.”

We have a few more such afterthoughts to discuss before we pull the curtain at last on the story of Infocom, that most detailed and extended of all the stories I’ve told so far on this blog. Now, however, it’s time to check in with Infocom’s counterparts on the other side of the Atlantic, with the other two of the three remaining companies in the English-speaking world still trying to make a living out of text adventures in 1988. As you have probably guessed, things weren’t working out all that much better for either of them than they were for Infocom. Yet amidst the same old commercial problems, there are still some interesting and worthy games to discuss. So, we’ll start to do just that next time.

(Sources: As usual with my Infocom articles, much of this one is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Much of it is also drawn from Jason’s “Infocom Cabinet” of vintage documents. Magazine sources include Questbusters of March 1989, The Games Machine of October 1989, and the Spring 1989 issue of Infocom’s The Status Line newsletter. Huge thanks also to Tim Anderson and Steve Meretzky for corresponding with me about some of the details of this period.

If you still want to play Zork Zero after the thrashing I’ve just given it — sorry, Steve and all Zork Zero fans! — you can purchase it from GOG.com as part of The Zork Anthology.)