At the crack of dawn on July 26, 1918, two S.E.5a scout planes of 85 Squadron took off from Saint-Omer aerodrome and flew east over the trenches. The pilots of the two aircraft could hardly have been more dissimilar in terms of experience. Donald Inglis, a stocky Kiwi, was a nervous newcomer with just a few prior sorties under his belt and as yet no victories to his credit. His flight leader and squadron commander, meanwhile, had recently claimed the title of Britain’s ace of aces, with 60 victories to show for many months of combat duty. He, of course, was Major Edward “Mick” Mannock.

Had he not been such a mess of frayed nerve endings, Mannock would have found 85 Squadron, a well-respected veteran unit, almost uniquely congenial to a man of his background and political disposition. It was an unusually egalitarian, even multicultural outfit, including in its ranks Brits, Aussies, Kiwis, Afrikaners, and even three American volunteers, all from many different social strata. The squadron’s composition was a sign of one of the too-few positive attributes of war, its tendency to show up fine distinctions of class and culture for the artificialities they really are. Few to none of Mannock’s charges could be bothered to worry overmuch about the circumstances of their new leader’s birth or the implications of his Irish accent. He was now simply their own Major Mannock, one of the most respected fighting airmen at the front.

Yet even as they respected him, they also found plenty of cause to worry about him — and thus, he being after all their leader, plenty of cause to worry about themselves. While Mannock had arrived in their mess hall on July 5 preaching the same gospel he had preached to 74 Squadron — about the importance of teamwork, discipline, and sound tactics as opposed to individual heroism — his conduct in the air had almost immediately begun to violate his own rules. He threw flights he was leading into battle when the odds or the positioning of his planes relative to the enemy’s called for making discretion the better part of valor, and he evinced an alarming new tendency to follow his kills all the way down to ground level in order to watch them crash, thereby giving up the precious advantage of height and leaving himself vulnerable to other enemy planes that might be lurking in the clouds above as well as small-arms fire coming up from below.

Most of his new squadron mates came to attribute his increasing foolhardiness, which was almost starting to look like a death wish, in one way or another to the death of his friend and rival ace James McCudden on July 9. Some said that Mannock’s frenzy to kill as many Germans as possible was an expression of his grief and anger at the loss. Others of a more cynical bent said that the death of McCudden with 57 victories to his credit gave Mannock a concrete, static goal to strive for in running up his own total. His eagerness to follow each kill down to its bloody end, they claimed, reflected his desire to fix an exact position of the crash so that he would stand the best possible chance of seeing the victory confirmed and thus added to his personal tally. But whatever his motivations or the needless dangers to which he exposed himself and others, he continued the torrid pace of his previous tour of duty. He matched and then surpassed McCudden’s total on the banner day of July 20, when he racked up his 57th, 58th, and 59th victories.

By this morning in question of July 26, the attempted German breakout of the previous spring had exhausted itself without achieving its objective, and now the inevitable Allied counteroffensive was beginning, aided by the hundreds of thousands of fresh-faced American soldiers now pouring into France. The activities of the Allied air forces were, as always, closely tied to the efforts of the armies on the ground. In support of the counteroffensive, they prowled the front in the ever larger formations allowed by the buzzing home-front factories and air schools, looking to down the outnumbered and exhausted remnants of Germany’s air force.

Unusually, however, Mannock and Inglis were flying all alone on this particular morning. As was his wont with new pilots, Mannock had promised Inglis that he would help him “break his duck” — i.e., help him score his first kill. The two of them were thus doing a bit of freelancing to the side of their squadron’s normal responsibilities, looking for a stray German plane or observation balloon that would serve their purpose while the rest of 85 Squadron slept in.

Most of the flight was uneventful. They explored as far into German airspace as they dared — their planes carried only enough fuel for about two and a half hours of flight — and then turned for home without having found any victims. But then, coming back toward the line of the front, Mannock shocked Inglis with a sudden turn and a dive to swoop down upon a two-man German observation craft that his companion had yet to even spot when Mannock’s guns began to bark. Mannock took out the German gunner with cold surgical precision, then banked away, signaling his companion to finish off their now-helpless quarry. A nervous Inglis waited too long to open fire and then waited too long to cut away, very nearly ramming the German plane from behind even as its fuel tank exploded. Still, he got the job done in the end; the hapless observation plane turned into a “flamer” for which the two pilots would share credit, marking Mannock’s 61st victory and Inglis’s very first.

Inglis thought that ought to be that, but, as usual these days, Mannock had other ideas. He followed their burning victim down through its death spiral of many thousands of feet, until it smashed into the ground just on the German side of the front. Not knowing what else to do, Inglis followed his leader down to a height of less than 100 feet, whereupon a hail of fire erupted from the ground, arcing up toward the two vulnerable planes. Dodging frantically and trying to regain some altitude, Inglis saw a tiny flicker of orange flame erupt from the fuselage of Mannock’s S.E.5a, turning into a bright contrail trailing out behind it as Mannock, still apparently alive and in control, managed to steady his plane and tear toward the Allied side of the front, evidently hoping to manage a crash landing over friendly territory.

He didn’t make it. His plane’s nose dipped and it veered into a slow right turn, making two lazy circles before it smashed into the ground. A line of flame arced along the ground, digging a new furrow into the scarred landscape. Inglis was so fixated on the sight that he very nearly suffered the same fate; he came to himself to realize that his plane was still being riddled by gunfire from somewhere below him, and that raw fuel was pouring into his lap out of a hole in the tank. He dashed for home, landing safely back at Saint-Omer, where he leaped out of his plane, covered in fuel and with tears streaming down his face, shouting incoherently, “They’ve shot him down!” Only gradually did the others make sense of what he was trying to tell them: Mick Mannock, their squadron commander of all of three weeks, was dead at the grand old age (for a World War I fighter pilot) of 31.

The aftermath of Mannock’s death was marked by none of the ceremony that had accompanied the death of the Red Baron. Unlike Manfred von Richthofen’s plane, Mannock’s scout bore no distinguishing marks, looking for all the world like just another anonymous S.E.5a. It had come to rest behind the German lines, and the soldiers who buried whatever remained of Mannock’s body in an unmarked grave never had an inkling that they were burying one of the greatest aces of the war. Because the location where they buried him was never recorded and his body was thus never recovered, we don’t know whether he made good on his promise to shoot himself at the last instant rather than allow himself to be burned alive, or whether he did indeed end up suffering the fate about which he’d had so many nightmares.

Even the British side paid surprisingly little attention to Mannock’s death. This was partly due to an official policy, noble in its way, that had been instituted after the press had elevated Albert Ball into one of the foremost heroes of the war. The war in the air, went the official line, was a team effort, and it wouldn’t do to unduly celebrate any of the individuals who fought it. While an exception had been allowed for the morale-boosting Canadian ace Billy Bishop, the British command otherwise hewed to this rule quite seriously.

And so the various squadrons posted up and down the Allied side of the front toasted him one last time with more or less feeling, and that was that. The war went on in the form of the great Allied offensive that finally succeeded in breaking through the German lines, sending the German armies into full-blown retreat and ending hostilities well before Christmas. Mannock would have needed to survive just a few more months of combat — and with the odds increasingly in his favor at that — to have become one of the war’s relatively few surviving aces. And yet one senses, given the condition he was in by the time of his death, that it might just as well have been a few more years.

Only after the war was over did Mannock begin to get some of the public acclamation that was his due. Ira Jones, still his greatest fan, lobbied relentlessly that his idol, the top-scoring British ace of the war, ought to be awarded Britain’s highest military honor, the Victoria Cross. It seemed to him the only fair thing to do; after all, the same honor had already been given to Billy Bishop, James McCudden, and Albert Ball. But if further impetus was needed to pressure the bureaucracy into action, Jones wasn’t above doing a little fudging. By being extremely generous in awarding “possible” kills, he was able to elevate Mannock’s victory count to a “probable” 73 — not coincidentally exactly one more than Billy Bishop, whose own total Jones, like so many others, regarded as highly questionable. Jones managed to find an ally for his cause in none other than Winston Churchill, and Mannock was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross on July 18, 1919. Mannock’s entire family, including his loathed father, now living in a bigamous relationship with a new wife and all too eager to claim kinship with the son he had physically abused and then abandoned, came to the ceremony. But thankfully, Mannock’s big brother Patrick was the one to take actual possession of the medal.

In the years that followed, the story of Mick Mannock, fighter ace, was elevated by hagiographers into a tale of duty, honor, and plucky English courage perfect for a generation of schoolboys raised on Biggles. While Mannock’s story may have lacked some of the flash and color that clung to that of the steely Red Baron or the tender boy ace Albert Ball, as the acknowledged British ace of aces he certainly had the numbers to support his claim to a place in the pantheon of British military heroism. In an effort to give his story that little something extra, the hagiographers invented the legend of “the ace with one eye.” Mannock, they decided on the basis of scant evidence, had accomplished all he had in the air while being blind in one eye, thanks to the amoebic infection he had contracted during his boyhood in India. Such was his burning desire to fight for the British crown in the air, the place where he felt he could do the most good, that he had kept the condition hidden from virtually everyone. Inevitably, it was Ira Jones who laid it on thickest of all in his popular 1934 biography King of Airfighters, inventing treacly speeches for his idealized Mannock that would never have passed the lips of the rough-hewn working-class man of reality. (“Don’t forget that when you see that tiny spark come out of my S.E.,” Mannock supposedly told him near the end, “it will kindle a flame which will act as a torch to guide the future air defenders of the Empire along the path of duty.”)

All of which is at one level fair enough. We need our heroes; we even need our myths. At another level, though, the real world is not a Biggles novel, and shrouding Mick Mannock so relentlessly in Union Jacks and Rule Britannias can only serve to diminish the real man behind the myth. At bottom, his story is inspiring because it is so messy, not in spite of it. The darker, more disturbing aspects of it — his oft-expressed hatred of the entire German race, his struggles to reconcile personal glory with the demands of the war effort as a whole — are the shades and nuances that identify him as a real human being rather than a walking, talking Royal Air Force recruitment poster. Like all of us, he had his demons. The fact that he accomplished so much in spite of them only serves to amplify those achievements, not to diminish them.

Through all their cheap patriotic sentiment, the Ira Joneses of the world avoid asking the really hard questions about the social inequalities against which Mannock struggled for much longer than he fought the Germans, the inequalities which to the very end of his life conspired to deny him much of the credit that was his due. And then, of course, there are the hard questions about the war that killed him. In that war’s aftermath, some — most notably his old friend and fellow socialist Jim Eyles — speculated about what Mannock, a man of so much complexity and capability, might have gone on to had he lived. Would he have, as Eyles liked to believe, taken a more active role in politics than ever, possibly entering the fray himself as a candidate for office? What might he have accomplished for the working classes had he done so? Because of the war — because of a senseless, useless war that, unlike its sequel, in no way needed to be fought — we’ll never know. Multiply Mannock’s wasted potential by the millions of others whose lives were similarly ended too soon, and you begin to gain an appreciation for the real tragedy of war.

Mannock’s fame, such as it was, peaked in the 1930s following the publication of Jones’s book. With the onset of the Second World War and Winston Churchill’s “few” of Battle of Britain fame, British schoolboys found themselves new aviator heroes to admire, even though no British ace of that or any subsequent war would ever equal Mannock’s victory tally. By the 1950s Mannock was already fading into obscurity, a name known only to aviation buffs and military-history fans. Today very few people indeed would recognize his name.

Still, in the interregnum between then and now there was one other tribute — a tribute that was never explicitly labeled as such, yet one that got in its own flawed way to some of the nuance of Mannock’s story that Ira Jones and his flag-waving contemporaries had missed…

In 1989, more than seventy years after Mick Mannock’s S.E.5a went down in flames, Bob Jacob, head of the American computer-game developer Cinemaware, called John Cutter, one of his most reliable designers and producers, into his office to assign him his next project. Jacob, who almost always personally chose the topics of his company’s trademark “interactive movies,” had decided that Cinemaware ought to make a sort of cinematic flight simulator set during World War I. As usual, he had drawn his inspiration from an old movie, but this time he had in lieu of his usual beloved B-movie fare fixated on a big-budget blockbuster of bygone years: William Wellman’s 1927 silent classic Wings, the first movie to win the newly minted Academy Award for Best Picture. Many actual veterans of the First World War had been recruited for the film, to perform the flying sequences in the actual aircraft they had flown into battle; the aerial footage that resulted remains some of the most incredible ever filmed. Because Wings, like many movies of its era, had a somewhat doubtful copyright status, it should be safe to crib from it even more than was Cinemaware’s usual wont, to the extent of blatantly appropriating its title alongside its spirit of aerial derring-do. Beyond that, Jacob, who was always more interested in the big picture than the details of Cinemaware’s productions, would leave it up to Cutter.

For his part, Cutter was rather taken aback by this turn of events, wondering just how many times he would be expected to channel Jacob’s personal passions instead of his own. He had just finished bringing another of Jacob’s ideas to fruition, a game starring the old vaudeville comedy troupe The Three Stooges. Now he was being asked to make a game based on yet another subject he knew nothing about and frankly wasn’t all that interested in. But needs must. So, figuring he had to start somewhere, he made his way down to the local library to do some reading on World War I in the air. “What incredible stories I read that afternoon!” he later remembered. “They were personal accounts of unbelievable courage and dedication — reflections of man’s indomitable spirit struggling valiantly against his enemies, the elements, and the dangers of an infant technology.” In the space of those few hours in the reading stacks, he went from a man with a job to do and little more to a man on a mission. The cinematic take on the air war of Wings the movie, sometimes spectacular though it was, faded into the background in favor of the real stories of the men who had flown and fought all those years ago. The end result would be unique in the Cinemaware catalog, otherwise made up of blatantly artificial third-hand pastiches of history filtered through this or that cinematic inspiration. Cutter’s Wings, by contrast, would demonstrate a willingness to engage with the real stuff of history.

Cutter found the real-world document that came to hover over the project, giving it much of its form and tone, when he visited the archives of the San Diego Aerospace Museum to further his research. Said document was a slim volume, published briefly in facsimile form by a small British press in 1966, called The Personal Diary of “Mick” Mannock. It was exactly what the title said it was: a diary kept by Mannock between April 1, 1917, the date he arrived in France as a shaky greenhorn pilot, and September 5, 1917, by which time he had found ways to cope with the terrors of airborne warfare and was beginning to make his name as an up-and-coming ace to be reckoned with.

The diary is, it must be said, a rather underwhelming document at first glance. Those who hope for exciting accounts of aerial jousts must be as disappointed as those who hope for rigorous psychological self-analysis. Mannock was no poet, and certainly not conscious of writing for any posterity other than himself. His diary is just that, a personal diary, filled with terse reminders of what happened on this or that day. And even on those terms, it covers the barest fraction of Mannock’s combat career, ending when he had scored just 11 of his eventual 61 victories and before he had really begun to implement the policies of aerial teamwork and unit discipline that would, over and above his personal victory tally, be his most important contribution to the British war effort. Yet when you spend more time with the diary your interest only grows, despite or perhaps because of its sketchy, underwritten prose. You begin to pick up on the rhythms of this strange life, with its horrors always lurking suppressed just below the surface. In bare sentences here and there, you learn about champagne blowouts, brawls in the mess hall, accidents and mishaps in the air and on the ground, alongside the relentless litany of fallen comrades. (“Poor old Pendor is missing since Wednesday, as also is Cullen. I hope both are alright. Poor old Bond is gone and I see that they have awarded him a posthumous D.S.O. Cold comfort!”)

Mannock’s diary, at first so underwhelming but then so fascinating, inspired the unique structure of Cutter’s game: a sort of epistolary novel in interactive form. Through hundreds of diary entries of its own, written by a screenwriter named Ken Goldstein, Wings tells the story of the air war on the Western Front, spanning from March 2, 1916, the dawn of the classic era of World War I dogfighting, through November 10, 1918, the very end of the war. In between the diary entries, you fly missions which reflect, as well as possible within the boundaries of the game’s very limited scope of interactive possibility, the events swirling around the squadron to which you belong. You strafe enemy ground emplacements and convoys; you bomb enemy camps and aerodromes; you go after enemy observation balloons. But most of all, you dogfight — you dogfight a lot, hundreds of times as you work your way through those hundreds of diary entries. The pilot whose actions you guide climbs the rungs of the ace leader board as together you shoot down enemy planes. He also collects medals and promotions, and his skills in the disciplines of “flying,” “mechanics,” “shooting,” and “stamina” improve, CRPG-fashion, as he practices them.

I have to acknowledge right now that Wings is by many standards not a very good game at all. Optimistically labelled a flight simulator by Cinemaware, it’s far from worthy of that label by most people’s standards. Instead it’s a collection of fairly simplistic action games whose appeal isn’t helped all that much by the fact that you have to play them so many times; no prior Cinemaware game took anywhere near as long to play through as this one, and few had a bag of tricks quite so limited. The dogfighting game, the one you’ll spend by far the most time with, might just be the least compelling of all; it feels too slow running on a stock 68000-based Commodore Amiga (the only platform for which the game was released), yet seems to run too fast on an upgraded 68020-based machine.

Even the case for the diary’s literary worth can be all too easily overstated. There’s enough empty rah!-rah! sentiment therein to make Ira Jones proud, alongside the occasional factual howler, like the mechanic with your British squadron who dreams of opening an auto-repair shop back home in Vermont after the war (in the meantime, he goes to bed each night dreaming about driving his father’s Model T Ford). Yet redeeming the whole are a succession of interesting characters and touching vignettes, many of them transplanted, with names changed and situations altered to a greater or lesser degree, out of the diary of the game’s patron saint Mick Mannock. For instance, B.W. Keymer, 40 Squadron’s earthy chaplain who did so much to help Mannock overcome his rocky start in the mess hall, takes the form in the game of a chaplain named “Holy Joe” who is likewise more concerned with helping his charges make it through another day of war than he is with standing on conventional religious ceremony.

Very early on, a captured German says that his comrades’ intention is to “bleed France white,” a disturbingly evocative phrase that was actually uttered by German General Erich von Falkenhayn as a justification for the carnage of the Battle of Verdun. Already here the horror of war is beginning to sneak in around all the exhortations to martial glory. Disillusion soon begins to affect our pilot and scribe as well.

July 13, 1916:

Patrolling Verdun this morning. I’m starting to realize how much the trenches are haunting me. I’ve got friends out there rotting in the musty earth, and the war is still no closer to ending than the day I volunteered. With all the military brilliance on our payroll, someone must know how to break the stalemate.

The diary reaches a fever pitch during the most desperate month of the war for the Royal Flying Corps: that Bloody April of 1917, the month of Mick Mannock’s baptism by fire. During this period in particular, Wings is willing to depict a side of war that we too seldom see in videogames.

April 12, 1917:

Farrah’s mole reports that the Germans have indeed changed their fighting strategy. Richthofen’s Jagdstaffel 11 has been expanded into what’s being called a “Jagdgeschwader,” a fighter wing. Three separate Jagdstaffeln of murderous planes are now at his beck and call.

Farrah says we should ignore this and fly today’s patrol as if nothing has changed. That would require a blindfold.

April 14, 1917:

No one here wants to fly. The Richthofen Geschwader is at peak performance. They’re pummeling us even worse than in the days of the Fokker Scourge. While Holy Joe is trying desperately to hold morale together, Farrah is stone cold and has ordered me and three others to patrol Arras at dawn. I think our C.O. is losing perspective. At the very least, he is losing the respect of his men.

April 16, 1917:

In all the mayhem our dog Barkley cowers at night alone. Each day, he loses another friendly hand to pat his head, to scratch behind his ears, to slip him tidbits under the table. Poor Barkley. Poor us.

April 24, 1917:

Some good news. Due to the valiant efforts of the Canadian troops, the British have taken Vimy Ridge! I wish I could report similar victory in the skies. It seems this bloody month will never end, that Richthofen has gained the edge in air superiority. Pilots across the front are weary and losing faith in Wing HQ. We need success on today’s patrol over Douai or our nerve may be forever shattered.

April 27, 1917:

Blood! Blood everywhere! The men are begging not to go up. Each time a sortie is dispatched someone returns grumbling, “That dirty butcher Farrah!” Just as French soldiers have begun to mutiny, we’ve considered rising up against our C.O. When he assigned four of us to patrol Arras after breakfast, I heard someone grumble, “Why doesn’t he just carve us up with a meat cleaver?”

April 29, 1917:

As our troops reclaim territory vacated by the enemy for the Hindenburg Line, we have little to celebrate. Before the Huns left, they leveled buildings, blocked roads, and contaminated water bins. General Ludendorff has served his nation well. He makes me sick.

Those of us at Amiens still willing to fly will patrol Ostend this afternoon. We can only hope the Flying Circus is on a coffee break.

April 30, 1917:

Responding to threats of mutiny, Farrah took heart and told us last night how much he hates to send young pilots like us to our deaths.

May 2, 1917:

Holy Joe has been doing all he can to get more wheelchairs here. With a shortage of hospital beds throughout the Allied camps, Amiens has been turned into an emergency treatment center. All around us there are countless soldiers with hideous stumps in place of their limbs. I’m left feeling queasy, jittery, ever the more wary of today’s patrol to Cambrai.

May 7, 1917:

Strange murmurings around camp. For the first time, pilots are quietly admitting they’re afraid. With Bloody April fresh in our minds, it’s suddenly become very realistic that we could die up there. We see death every day, but now we believe it can really happen to us. With five of us off to patrol Lille this afternoon, we all know it’s unlikely that we’ll all come back.

May 11, 1917:

Tremendous sorrow in writing tonight’s entry. The great British pilot Albert Ball is reported to be dead. Some say he was shot down by the Baron’s brother, Lothar. Others allege that he just disappeared into a cloud after being hit by gunfire from a church tower. I will think of him as I fly tomorrow’s patrol over Douai, praying I won’t die in a similar shroud of mystery.

One of Wings‘s most brilliant rhetorical devices is also its most chilling. When your pilot gets shot down and killed, the game doesn’t end. You rather simply create a new pilot to plunge back into the fray right where you left off — another replacement greenhorn dispatched to the front to plug the hole of another man’s death. Only when it’s all over, when you’ve played through the entire two and a half years of the diary with however many pilots that’s taken, do you see a final scroll of honor, listing each pilot along with his dates of birth and death. It looks, I presume by intention, like one of the many plaintive memorials to the war dead found in towns and villages throughout Britain.

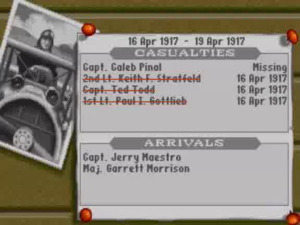

One other way that Wings shows the toll of war is via your squadron’s relentless roll call of casualties and new arrivals. Unless you’re ridiculously good, your own pilots will show up here on more than one occasion before you make it through the entire two and a half years of war which the game portrays.

With its interactive parts being so simplistic and repetitive, Wings must rise or fall in you the player’s estimation entirely on the basis of whether and to what extent the diary passages and the other background rhetorical flourishes manage to move you. In a sense, this was an old story for Cinemaware by the time of Wings, one reaching all the way back to the company’s breakthrough interactive movie Defender of the Crown. In Wings, however, the gilding on the lily of game play evinces a degree of humanity — a degree of soul — to which no other alleged “flight simulator” has ever even aspired.

Those other flight simulators define realism as getting all the knobs and switches right, making sure all the engines and airfoils and weaponry are in place and accounted for. Spectrum Holobyte’s Falcon, the king of the hardcore military flight simulators at the time that Cinemaware was working on Wings, came with a manual of more than 150 pages which read like a university engineering text (by the time of Falcon 3.0 in 1991, it would reach a downright Gygaxian 250 pages). Wings was a reaction against that aesthetic. Instead of building a game out of exhaustive technical detail, with no thought whatsoever given to the fragile human being ensconced there in the cockpit in the midst of it all, John Cutter asked what it was like to really be there as a pilot on the Western Front during World War I — asked what, speaking more generally, it really means to be a soldier at war. Michael Bate, a game designer for Accolade during the 1980s, called this approach “aesthetic simulation” — i.e., historical realism achieved not through technical minutiae but through texture and verisimilitude. The aesthetic simulation of Wings is a very different sort of simulation than the technical simulation of Falcon, but is, I would argue, no less worthy of the label for all that. At the end of his manual, Cutter wrote that “I can only pray that Wings will be remembered for its ability to educate and entertain, and not as a glorification of war.” In a medium that so often seems to do little but glorify war and others forms of violence, that stands out as a noble sentiment indeed. War, Wings tells us, has consequences. If the game never achieves more than a fraction of what it aspires to accomplish, that fact at least justifies a certain admiration.

And Wings also is well worth admiring as a loving final memorial to our old friend Major Edward “Eddie/Paddy/Pat/Jerry/Murphy/Mickey/Mick” Corringham Mannock, who is in turn a man worth admiring not because the things he did were easy for him but because they were hard, not because he was an unalloyed good person but because he aspired to be that person. Unlike Albert Ball, Mannock goes unmentioned in Wings‘s diary; this makes a degree of sense if one considers you the player to be to some extent playing the role of Britain’s diary-keeping ace of aces. On the date of his death, however, the game does see fit to give us an unusually lyrical diary passage. I like to believe that this isn’t a coincidence, that it’s intended as a final subtle tribute.

July 26, 1918:

Yesterday I was reminded of what a magical experience it is to fly. As I practiced turning through the soft white clouds, I experienced the sheer joy of defying gravity. The tapering horizon, the mountainous landscape, even patches of the shell-weary fields held fragments of beauty. I dreamed of flying endless hours in peaceful skies.

May all our own skies evermore be peaceful.

(Sources: In addition to those listed in the first article in this series, The One of March 1990, Matt Barton’s interviews with John Cutter and Bob Jacob, and “…and a Prayer: The Making of Wings” on Kaiju Pop!

Wings is available for purchase today in two forms. You can buy the original version shown in the movie and screenshots above in a package with most of Cinemaware’s other games, or you can buy a recent quite impressive remastered version. The remaster is likely to strike modern buyers as far more playable than the original, and is probably the version of choice for all but hardcore historians like yours truly.)

TsuDhoNimh

December 9, 2016 at 6:34 pm

Typo correction:

“German observation craft that his companion hat yet to even spot when…”

hat -> had

Jimmy Maher

December 9, 2016 at 6:58 pm

Thanks!

Sir Harrok

December 9, 2016 at 10:39 pm

Awesome. Should ‘Hail Britannia’ be Rule Britannia’ though?

Jimmy Maher

December 9, 2016 at 10:49 pm

Yes, that’s better isn’t it? Thanks!

Benjamin Bilgri

December 14, 2016 at 11:03 pm

This blog is pretty amazing; I’ve been working through your back catalog over the course of the last year or so. I was wondering whether you could recommend any other computer game history blogs that complement your own work. I noticed you linked to Alex Smith’s They Create Worlds a while back, and he provides a great overview of gaming’s earliest days, but currently only goes up to about 1972. Any other historians that do similarly rigorous work that you (or anybody else) could suggest would be hugely welcome.

Thanks for the phenomenal reading material.

Jimmy Maher

December 15, 2016 at 8:47 am

Alex is still working on his three-book history of the videogame industry, for which I have high hopes. Otherwise, there are other folks working similar territory, but their work tends to be more nostalgia-driven and uncritical than what I (hopefully) do here. Still, Retro Gamer magazine may be something you’d want to check out to see if their editorial tone agrees with you. I use their articles here from time to time, although they tend to be largely regurgitations of interviews and thus often have to be taken with a grain of salt.

Bernie

January 14, 2017 at 10:39 pm

Many thanks for your great work !

And, if I may be so bold, some additional comment on Benjamin’s post : there’s absolutely no other blog like Jimmy’s, and believe me when I say that I’ve searched and read a lot. Jimmy’s work is totally unique and an essential contribution to an still-evolving field. He is a true pioneer.

Now, onto my comment on Magnetic Scrolls :

The idea that Magnetic Scrolls was following in Miscrosoft’s footsteps regarding GUI design is very sharp and implies that their platform was doomed from the start. All that layering on top of MS-DOS was simply too inefficient for the target hardware. In my humble opinion, they should have followed Apple’s example, and Woz’s teachings, and “do it ALL in software”. For their GUI to work like it should, they would’ve had to develop their kernal routines in machine language, including drivers for the screen, mouse, etc. and load them directly in the BIOS’s “protected mode” (available in the i-286 processor and later). This is what Brian Dougherty and his team did with GEOS and managed to bring a very sophisticated GUI to the C-64, using half the RAM that Apple did with the Mac 128. They just switched out Commodore’s kernal and disk routines and loaded their own optimized code. I’m not sure if you could do this on Macs and Amigas, but their kernals were “GUI-friendly” and surely adequate if the porting was done with care. But the 286-based clones typical in the MSDOS world of the era would have worked well enough with some sort of boot disk, which could also include hard-disk drivers compatible with the MS file system.

Maybe this approach would have required less manpower and financial resources than the “Windows-route”, which entailed retooling MSDOS itself and waiting for average hardware specs to catch up, like Microsoft did.

Bernie

January 14, 2017 at 10:45 pm

Sorry Guys !

This reply is for a “future post” (Endings – part 3) , I messed up. Please disregard.

JIMMY , PLEASE DELETE MY POST. I will re-post on the correct article !

DZ-Jay

May 14, 2017 at 9:45 pm

I see by the number of comments that not many people made it this far…

I think it was a great story and told in a very romantic, interesting, and humane way. However, it’s not the sort of things I came to this blog for, so there’s that.

Perhaps the author gets bored with writing only about video games and tries to venture into other territories. Good for him, but perhaps another blog for those stories would serve him better?

dZ.

Kevin

September 12, 2017 at 1:13 am

This blog – and this series of posts in particular – really is masterful. Just superb stuff.

Wouter Lammers

April 30, 2019 at 8:51 pm

I’m still slowly making my way through the full history of this blog. I’m looking forward to the day that I can leave a meaningful comment (or even a correction!) on a current post, that’ll be the day!

In the meantime I just wanted to say that I enjoyed this little deviation a lot. I see that the nature of this blog dictates the need for the little Wings epilogue, but it almost felt a little out of place, the jump was a bit jarring!

I smiled when I saw the credits for Computography and Additional Computography. Is that just a very fancy word for graphics?! :)

Wolfeye M.

September 28, 2019 at 8:23 pm

I’m part English and part German, but I’m pretty sure both roots of my family tree were in the USA before WW1. Still, odd to think of being related to both sides of both WW1 and WW2. I had a great uncle who fought in, and survived, both wars flying planes. I don’t know much about him beyond that. So, in a way, it was nice to read about the experiences of the pilots like him, as horrible as they were.

I don’t think that the Red Baron expected to go down to a luck shot from ground fire. It was a bit anticlimactic, and very sad. Same for how Mancock died, his strange predilection for following the planes he shot down did him in. I think pointing to those two deaths, in the millions that happened, shows just how stupid gloryfing war is. Neither died as a fighter ace, going down in flames in a blaze of glory, under the guns of an enemy pilot.

Steve

August 24, 2020 at 6:50 am

Thanks for writing this. I found it very interesting and humbling. What people like Mick went through puts things into perspective.

Ben

February 28, 2024 at 11:12 pm

Carringham -> Corringham

_RGTech

April 5, 2025 at 3:11 pm

I’m not sure if it has always been this way, but the title picture (the memorial) needs to be rotated 90°.

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2025 at 7:43 am

Thanks!