Covert Action‘s cover is representative of the thankfully brief era when game publishers thought featuring real models on their boxes would drive sales. The results almost always ended up looking like bad romance-novel covers; this is actually one of the least embarrassing examples. (For some truly cringeworthy examples of artfully tousled machismo, see the Pirates! reissue or Space Rogue.)

In the lore of gaming there’s a subset of spectacular failures that have become more famous than the vast majority of successful games. From E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial to Daikatana to Godus, this little rogue’s gallery inhabits its own curious corner of gaming history. The stories behind these games, carrying with them the strong scent of excess and scandal, can’t help but draw us in.

But there are also other, less scandalous cases of notable failure to which some of us continually return for reasons other than schadenfreude. One such case is that of Covert Action, Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley’s 1990 game of espionage. Covert Action, while not a great or even a terribly good game, wasn’t an awful game either. And, while it wasn’t a big hit, nor was it a major commercial disaster. By all rights it should have passed into history unremarked, like thousands of similarly middling titles before and after it. The fact that it has remained a staple of discussion among game designers for some twenty years now in the context of how not to make a game is due largely to Sid Meier himself, a very un-middling designer who has never quite been able to get Covert Action, one of his few disappointing games, out of his craw. Indeed, he dwells on it to such an extent that the game and its real or perceived problems still tends to rear its head every time he delivers a lecture on the art of game design. The question of just what’s the matter with Covert Action — the question of why it’s not more fun — continues to be asked and answered over and over, in the form of Meier’s own design lectures, extrapolations on Meier’s thesis by others, and even the occasional contrarian apology telling us that, no, actually, nothing‘s wrong with Covert Action.

What with piling onto the topic having become such a tradition in design circles, I couldn’t bear to let Covert Action‘s historical moment go by without adding the weight of this article to the pile. But first, the basics for those of you who wouldn’t know Covert Action if it walked up and invited you to dinner.

As I began to detail in my previous article, Covert Action‘s development at MicroProse, the company at which Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley worked during the period in question, was long by the standards of its time, troubled by the standards of any time, and more than a little confusing to track in our own time. Begun in early 1988 as a Commodore 64 game by Lawrence Schick, another MicroProse designer, it was conceived from the beginning as essentially an espionage version of Sid Meier’s earlier hit Pirates! — as a set of mini-games the player engaged in to affect the course of an overarching strategic game. But Schick found that he just couldn’t get the game to work, and moved on to something else. And that would have been that — except that Sid Meier had become intrigued by the idea, and picked it up for his own next project, moving it in the process from the Commodore 64 to MS-DOS, where it would have a lot more breathing room.

In time, though, the enthusiasm of Meier and his assistant designer Bruce Shelley also began to evaporate; they started spending more and more time dwelling on an alternative design. By August of 1989, they were steaming ahead with Railroad Tycoon, and all work on Covert Action for the nonce had ceased.

After Railroad Tycoon was completed and released in April of 1990, Meier and Shelley returned to Covert Action only under some duress from MicroProse’s head Bill Stealey. With the idea that would become Civilization already taking shape in Meier’s head, his enthusiasm for Covert Action was lower than ever, but needs must. As Shelley tells the story, Meier’s priorities were clear in light of the idea he had waiting in the wings. “We’re just getting this game done,” Meier said of Covert Action when Shelley tried to suggest ways of improving the still somehow unsatisfying design. “I’ve got to get this game finished.” It’s hard to avoid the impression that in the end Meier simply gave up on Covert Action. Yet, given the frequency with which he references it to this day, it seems equally clear that that capitulation has never sat well with him.

Covert Action casts you as the master spy Max Remington — or, in a nice nod to gender equality that was still unusual in a game of this era, as Maxine Remington. Max is the guy the CIA calls when they need someone to crack the really tough cases. The game presents you with a series of said tough cases, each involving a plot by some combination of criminal and/or terrorist groups to do something very bad somewhere in the world. Your objective is to figure out what group or groups are involved, figure out precisely what they’re up to, and foil their plot before they bring it to fruition. As usual for a Sid Meier game, you can play on any of four difficulty levels to ensure that everyone, from the rank beginner to the most experienced super-sleuth, can be challenged without being overwhelmed. If you do your job well, you will arrest the person at the top of the plot’s org chart, one of the game’s 26 evil masterminds. Once no more masterminds are left to arrest, Max can walk off into the sunset and enjoy a pleasant retirement, confident that he has made the world a safer place. (If only counter-terrorism was that easy in real life, right?)

The game lets Max/Maxine score with progressively hotter members of the opposite sex as he/she cracks more cases.

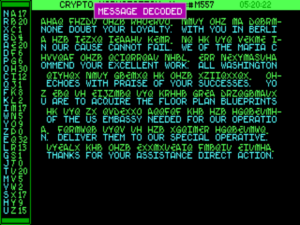

The strategic decisions you make in directing the course of your investigation will lead to naught if you don’t succeed at the various mini-games. These include rewiring a junction box to tap a suspect’s phone (Covert Action presents us with a weirdly low-tech version of espionage, even for its own day); cracking letter-substitution codes to decipher a suspect’s message traffic; tailing or chasing a suspect’s car; and, in the most elaborate of the mini-games, breaking into a group’s hideaway to either collect intelligence or make an arrest.

Covert Action seems to have all the makings of a good game — perhaps even another classic like its inspiration, Pirates!. But, as Sid Meier and most of the people who have played it agree, it doesn’t ever quite come together to become an holistically satisfying experience.

It’s not immediately obvious just why that should be the case; thus all of the discussion the game has prompted over the years. Meier does have his theory, to which he’s returned enough that he’s come to codify it into a universal design dictum he calls “The Covert Action rule.” For my part… well, I have a very different theory. So, first I’ll tell you about Meier’s theory, and then I’ll tell you about my own.

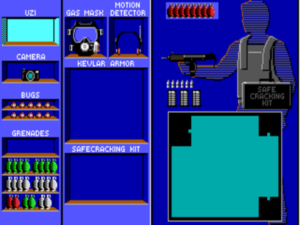

Meier’s theory hinges on the nature of the mini-games. He doesn’t believe that any of them are outright bad by any means, but does feel that they don’t blend well with the overarching strategic game, resulting in a lumpy stew of an experience that the player has trouble digesting. He’s particularly critical of the breaking-and-entering mini-game — a “mini-game” complicated enough that one could easily imagine it being released as a standalone game for the previous generation of computers (or, for that matter, for Covert Action‘s contemporaneous generation of consoles). Before you begin the breaking-and-entering game, you must choose what Max will carry with him: depending on your goals for this mission, you can give him some combination of a pistol, a sub-machine gun, a camera, several types of grenades, bugs, a Kevlar vest, a gas mask, a safe-cracking kit, and a motion detector. The underground hideaways and safe houses you then proceed to explore are often quite large, and full of guards, traps, and alarms to avoid or foil as you snoop for evidence or try to spirit away a suspect. You can charge in with guns blazing if you like, but, especially at the higher difficulty levels, that’s not generally a recipe for success. This is rather a game of stealth, of lurking in the shadows as you identify the guards’ patrol patterns, the better to avoid or quietly neutralize them. A perfectly executed mission in many circumstances will see you get in and out of the building without having to fire a single shot.

The aspect of this mini-game which Meier pinpoints as its problem is, somewhat ironically, the very ambition and complexity which makes it so impressive when considered alone. A spot of breaking and entering can easily absorb a very tense and intense half an hour of your time. By the time you make it out of the building, Meier theorizes, you’ve lost track of why you went in in the first place — lost track, in other words, of what was going on in the strategic game. Meier codified his theory in what has for almost twenty years been known in design circles as “the Covert Action rule.” In a nutshell, the rule states that “one good game is better than two great ones” in the context of a single game design. Meier believes that the mini-games of Covert Action, and the breaking-and-entering game in particular, can become so engaging and such a drain on the player’s time and energies that they clash with the strategic game; we end up with two “great games” that never make a cohesive whole. This dissonance never allows the player to settle into that elusive sense of total immersion which some call “flow.” Meier believes that Pirates! works where Covert Action doesn’t because the former’s mini-games are much shorter and much less complicated — getting the player back to the big picture, as it were, quickly enough that she doesn’t lose the plot of what the current situation is and what she’s trying to accomplish.

It’s an explanation that makes a certain sense on its face, yet I must say that it’s not one that really rings true to my own experiences with either games in general or Covert Action in particular. Certainly one can find any number of games which any number of players have hugely enjoyed that seemingly violate the Covert Action rule comprehensively. We could, for instance, look to the many modern CRPGs which include “sub-quests” that can absorb many hours of the player’s time, to no detriment to the player’s experience as a whole, at least if said players’ own reports are to be believed. If that’s roaming too far afield from the type of game which Covert Action is, consider the case of the strategy classic X-Com, one of the most frequently cited of the seeming Covert Action rule violators that paradoxically succeed as fun designs. It merges an overarching strategic game with a game of tactical combat that’s far more time-consuming and complicated than even the breaking-and-entering part of Covert Action. And yet it must place high in any ranking of the most beloved strategy games of all time. As we continue to look at specific counterexamples like X-Com or, for that matter, Pirates!, we can only continue to believe in the Covert Action rule by applying lots of increasingly tortured justifications for why this or that seemingly blatant violator nevertheless works as a game. So, X-Com, Meier tells us, works because the strategic game is relatively less complicated than the tactical game, leaving enough of the focus on the tactical game that the two don’t start to pull against one another. And Pirates!, of course, is just the opposite.

I can only say that when the caveats and exceptions to any given rule start to pile up, one is compelled to look back to the substance of the rule itself. As nice as it might be for the designers of Covert Action to believe the game’s biggest problem is that its individual parts were just each too darn ambitious, too darn good, I don’t think that’s the real reason the game doesn’t work.

So, we come back to the original question: just what is the matter with Covert Action? I don’t believe that Covert Action‘s core malady can be found in the mini-games, nor for that matter in the strategic game per se. I rather believe the problem is with the mission design and with the game’s fiction — which, as in so many games, are largely one and the same in this one. The cases you must crack in Covert Action are procedurally generated by the computer, using a set of templates into which are plugged different combinations of organizations, masterminds, and plots to create what is theoretically a virtually infinite number of potential cases to solve. My thesis is that it’s at this level — the level of the game’s fiction — where Covert Action breaks down; I believe that things have already gone awry as soon as the game generates the case it will ask you to solve, well before you make your first move. The, for lack of a better word, artificiality of the cases is never hard to detect. Even before you start to learn which of the limited number of templates are which, the stories just feel all wrong.

Literary critics have a special word, “mimesis,” which they tend to deploy when a piece of fiction conspicuously passes or fails the smell test of immersive believability. Dating back to classical philosophy, “mimesis” technically means the art of “showing” a story — as opposed to “diegesis,” the art of telling. It’s been adopted by theorists of textual interactive fiction as well as a stand-in for all those qualities of a game’s fiction that help to immerse the player in the story, that help to draw her in. “Crimes against Mimesis” — the name of an influential Usenet post written in 1996 by Roger Giner-Sorolla — are all those things, from problems with the interface to obvious flaws in the story’s logic to things that just don’t ring true somehow, that cast the player jarringly out of the game’s fiction — that reveal, in other words, the mechanical gears grinding underneath the game’s fictional veneer. Covert Action is full of these crimes against mimesis, full of these gears poking above the story’s surface. Groups that should hate each other ally with one another: the Colombian Cartel, the Mafia, the Palestine Freedom Organization (some names have been changed to protect the innocent or not-so-innocent), and the Stasi might all concoct a plot together. Why not? In the game’s eyes, they’re just interchangeable parts with differing labels on the front; they might as well have been called “Group A,” “Group B,” etc. When they send messages to one another, the diction almost always rings horribly, jarringly wrong in the ears of those of us who know what the groups represent. Here’s an example in the form of the Mafia talking like Jihadists.

If Covert Action had believable, mimetic, tantalizing — or at least interesting — plots to foil, I submit that it could have been a tremendously compelling game, without changing anything else about it. Instead, though, it’s got this painfully artificial box of whirling gears. Writing in the context of the problems of procedural generation in general, Kate Compton has called this the “10,000 Bowls of Oatmeal Problem.”

I can easily generate 10,000 bowls of plain oatmeal, with each oat being in a different position and different orientation, and mathematically speaking they will all be completely unique. But the user will likely just see a lot of oatmeal. Perceptual uniqueness is the real metric, and it’s darn tough. It is the difference between an actor being a face in a crowd scene and a character that is memorable.

Assuming that we can agree to agree, at least for now, that we’ve hit upon Covert Action‘s core problem, it’s not hard to divine how to fix it. I’m imagining a version of the game that replaces the infinite number of procedurally-generated cases with 25 or 30 hand-crafted plots, each with its own personality and its own unique flavor of intrigue. Such an approach would fix another complaint that’s occasionally levied against Covert Action: that it never becomes necessary to master or even really engage with all of its disparate parts because it’s very easy to rely just on those mini-games you happen to be best at to ferret out all of the relevant information. In particular, you can discover just about everything you need in the files you uncover during the breaking-and-entering game, without ever having to do much of anything in the realm of wire-tapping suspects, tailing them, or cracking their codes. This too feels like a byproduct of the generic templates used to construct the cases, which tend to err on the safe side to ensure that the cases are actually soluble, preferring — justifiably, in light of the circumstances — too many clues to too few. But this complaint could easily be fixed using hand-crafted cases. Different cases could be consciously designed to emphasize different aspects of the game: one case could be full of action, another more cerebral and puzzle-like, etc. This would do yet more to give each case its own personality and to keep the game feeling fresh throughout its length.

The most obvious argument against hand-crafted cases, other than the one, valid only from the developers’ standpoint, of the extra resources it would take to create them, is that it would exchange a game that is theoretically infinitely replayable for one with a finite span. Yet, given that Covert Action isn’t a hugely compelling game in its historical form, one has to suspect that my proposed finite version of it would likely yield more actual hours of enjoyment for the average player than the infinite version. Is a great game that lasts 30 hours and then is over better than a mediocre one that can potentially be played forever? The answer must depend on individual circumstances as well as individual predilections, but I know where I stand, at least as long as this world continues to be full of more cheap and accessible games than I can possibly play.

But then there is one more practical objection to my proposed variation of Covert Action, or rather one ironclad reason why it could never have seen the light of day: this simply isn’t how Sid Meier designs his games. Meier, you see, stands firmly on the other side of a longstanding divide that has given rise to no small dissension over the years in the fields of game design and academic game studies alike.

In academia, the argument has raged for twenty years between the so-called ludologists, who see games primarily as dynamic systems, and the narratologists, who see them primarily as narratives. Yet at its core the debate is actually far older even than that. In the December 1987 issue of his Journal of Computer Game Design, Chris Crawford fired what we might regard as the first salvo in this never-ending war via an article entitled “Process Intensity.” The titular phrase meant, he explained, “the degree to which a program emphasizes processes instead of data.” While all games must have some amount of data — i.e., fixed content, including fixed story content — a more process-intensive game — one that tips the balance further in favor of dynamic code as opposed to static data — is almost always a better game in Crawford’s view. That all games aren’t extremely process intensive, he baldly states, is largely down to the laziness of their developers.

The most powerful resistance to process intensity, though, is unstated. It is a mental laziness that afflicts all of us. Process intensity is so very hard to implement. Data intensity is easy to put into a program. Just get that artwork into a file and read it onto the screen; store that sound effect on the disk and pump it out to the speaker. There’s instant gratification in these data-intensive approaches. It looks and sounds great immediately. Process intensity requires all those hours mucking around with equations. Because it’s so indirect, you’re never certain how it will behave. The results always look so primitive next to the data-intensive stuff. So we follow the path of least resistance right down to data intensity.

Crawford, in other words, is a ludologist all the way. There’s always been a strongly prescriptive quality to the ludologists’ side of the ludology-versus-narratology debate, an ideology of how games ought to be made. Because processing is, to use Crawford’s words again, “the very essence of what a computer does,” the capability that in turn enables the interactivity that makes computer games unique as a medium, games that heavily emphasize processing are purer than those that rely more heavily on fixed data.

It’s a view that strikes me as short-sighted in a number of ways. It betrays, first of all, a certain programmer and systems designer’s bias against the artists and writers who craft all that fixed data; I would submit that the latter skills are every bit as worthy of admiration and every bit as valuable on most development teams as the former. Although even Crawford acknowledges that “data endows a game with useful color and texture,” he fails to account for the appeal of games where that very color and texture — we might instead say the fictional context — is the most important part of the experience. He and many of his ludologist colleagues are like most ideologues in failing to admit the possibility that different people may simply want different things, in games as in any other realm. Given the role that fixed stories have come to play in even many of the most casual modern games, too much ludologist rhetoric verges on telling players that they’re wrong for liking the games they happen to like. This is not to apologize for railroaded experiences that give the player no real role to play whatsoever and thereby fail to involve her in their fictions. It’s rather to say that drawing the line between process and data can be more complicated than saying “process good, data bad” and proceeding to act accordingly. Different games are at their best with different combinations of pre-crafted and generative content. Covert Action fails as a game because it draws that line in the wrong place. It’s thanks to the same fallacy, I would argue, that Chris Crawford has been failing for the last quarter century to create the truly open-ended interactive-story system he calls Storytron.

Sid Meier is an endlessly gracious gentleman, and thus isn’t so strident in his advocacy as many other ludologists. But despite his graciousness, there’s no doubt on which side of the divide he stands. Meier’s games never, ever include rigid pre-crafted scenarios or fixed storylines of any stripe. In most cases, this has been fine because his designs have been well-suited to the more open-ended, generative styles of play he favors. Covert Action, however, is the glaring exception, revealing one of the few blind spots of this generally brilliant game designer. Ironically, Meier had largely been drawn to Covert Action by what he calls the “intriguing” problem of its dynamic case generator. The idea of being able to use the computer to do the hard work of generating stories, and thereby to be able to churn out infinite numbers of the things at no expense, has always enticed him. He continues to muse today about a Sherlock Holmes game built using computer-generated cases, working backward from the solution of a crime to create a trail of clues for player to follow.

Meier is hardly alone in the annals of computer science and game design in finding the problem of automated story-making intriguing. Like his Sherlock Holmes idea, many experiments with procedurally-generated narratives have worked with mystery stories, that most overtly game-like of all literary genres; Covert Action‘s cases as well can be considered variations on the mystery theme. As early as 1971, Sheldon Klein, a professor at the University of Wisconsin, created something he called an “automatic novel writer” for auto-generating “2100-word murder-mystery stories.” In 1983, Electronic Arts released Jon Freeman and Paul Reiche III’s Murder on the Zinderneuf as one of their first titles; it allowed the player to solve an infinite number of randomly generated mysteries occurring aboard its titular Zeppelin airship. That game’s flaws feel oddly similar to those of Covert Action. As in Covert Action, in Murder on the Zinderneuf the randomized cases never have the resonance of a good hand-crafted mystery story. That, combined with their occasional incongruities and the patterns that start to surface as soon as you’ve played a few times, means that you can never forget their procedural origins. These tales of intrigue never manage to truly intrigue.

Suffice to say that generating believable fictions, whether in the sharply delimited realm of a murder mystery taking place aboard a Zeppelin or the slightly less delimited realm of a contemporary spy thriller, is a tough nut to crack. Even one of the most earnest and concentrated of the academic attempts at tackling the problem, a system called Tale-Spin created by James Meehan at Yale University, continued to generate more unmimetic than mimetic stories after many years of work — and this system was meant only to generate standalone static stories, not interactive mysteries to be solved. And as for Chris Crawford’s Storytron… well, as of this writing it is, as its website says, in a “medically induced coma” for the latest of many massive re-toolings.

In choosing to pick up Covert Action primarily because of the intriguing problem of its case generator and then failing to consider whether said case generator really served the game, Sid Meier may have run afoul of another of his rules for game design, one that I find much more universally applicable than what Meier calls the Covert Action rule. A designer should always ask, Meier tells us, who is really having the fun in a game — the designer/programmer/computer or the player? The procedurally generated cases may have been an intriguing problem for Sid Meier the designer, but they don’t serve the player anywhere near as well as hand-crafted cases might have done.

The model that comes to mind when I think of my ideal version of Covert Action is Killed Until Dead, an unjustly obscure gem from Accolade which, like Murder on the Zinderneuf, I wrote about in an earlier article. Killed Until Dead is very similar to Murder on the Zinderneuf in that it presents the player with a series of mysteries to solve, all of which employ the same cast of characters, the same props, and the same setting. Unlike Murder on the Zinderneuf, however, the mysteries in Killed Until Dead have all been lovingly hand-crafted. They not only hang together better as a result, but they’re full of wit and warmth and the right sort of intrigue — they intrigue the player. If you ask me, a version of Covert Action built along similar lines, full of exciting plotlines with a ripped-from-the-headlines feel, could have been fantastic — assuming, of course, that MicroProse could have found writers and scenario designers with the chops to bring the spycraft to life.

It’s of course possible that my reaction to Covert Action is hopelessly subjective, inextricably tied to what I personally value in games. As my longtime readers are doubtless aware by now, I’m an experiential player to the core, more interested in lived experiences than twiddling the knobs of a complicated system just exactly perfectly. In addition to guaranteeing that I’ll never win any e-sports competitions — well, that and my aging reflexes that were never all that great to begin with — this fact colors the way I see a game like Covert Action. The jarring qualities of Covert Action‘s fiction may not bother some of you one bit. And thus the debate about what really is wrong with Covert Action, that strange note of discordance sandwiched between the monumental Sid Meier masterpieces Railroad Tycoon and Civilization, can never be definitely settled. Ditto the more abstract and even more longstanding negotiation between ludology and narratology. Ah, well… if nothing else, it ensures that readers and writers of blogs like this one will always have something to talk about. So, let the debate rage on.

(Sources: the books Expressive Processing by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and On Interactive Storytelling by Chris Crawford; Game Developer of February 2013. Links to online sources are scattered through the article.

If you’d like to enter the Covert Action debate for yourself, you can buy it from GOG.com.)

Jason Lefkowitz

March 24, 2017 at 1:00 pm

And not just stories — see, for instance, his 1994 title C.P.U. Bach, which was an engine for generating infinite numbers of Baroque compositions.

Brian Roy

March 24, 2017 at 1:39 pm

I love Covert Action, but I have to admit that your criticisms ring pretty true, more true for my experiences than Mr. Meier’s hypothesis on the game anyway. Procedurally generated plots sound like a great feature. As you said, though, they very quickly start to feel “game-like” and “the gears poke through.” I even have considered intentionally not foiling plots when I pay sometimes, so that I could play through the second stage of the plot and get to experience more of the templates, as it doesn’t take long to realize how few each difficulty level really has.

All that said, it’s still got some really enjoyable minigames as far as I’m concerned. I love doing the wiretapping and cryptography games, personally, and in spite of its flaws, it’s a game I still enjoy.

Thank you, as always, for a great article, Jimmy.

AguyinaRPG

March 24, 2017 at 2:47 pm

Second paragraph, Meier is spelled “Meir”.

Also, “he baldly states”. For all I know that may have been the intention though!

I can’t say I’ve ever heard of Covert Action, though I might have to look a little deeper into it after watching a bit of footage for some context.

As to the whole ludology versus narrative divide, I’ve heard a lot of interesting arguments over the years. There’s a brief “History of Stealth Games” on Youtube where the guy makes the argument of both schools needing to be taken into account to define a Stealth Genre. I don’t necessarily agree with that,certainly in my own games and research I am a ludologist, but it’s a more nuanced point than I often hear where narrative becomes a stage just because people apparently can’t understand stories through -doing-. That’s not what you’re arguing, I can tell, but it’s the insinuation I get a lot.

I do think you’re too harsh on procedural generation, going all the way back to Murder on the Zinderneuf. I think that’s one of the greatest potentials for expressing the uniqueness of a story within a video game setting, None of these early games did it well when applying it to the narrative aspects, but I definitely think that it has been done well at some point (and perhaps you’ll cover that when we get there). I think the trick is not to randomly generate a *story* (yet) and instead alter certain aspects of it.

Jimmy Maher

March 24, 2017 at 3:00 pm

Your second correction was indeed as intended. Thanks for your thoughts!

AguyinaRPG

March 24, 2017 at 3:59 pm

Low blow Jimmy, low blow. (Though he deserves it)

Jimmy Maher

March 24, 2017 at 9:29 pm

Oh, I see what you mean. No pun was intended, although I could almost wish I was clever enough to have thought of that one. ;)

Pedro Timóteo

March 24, 2017 at 3:36 pm

First, great as always. I played a lot of this game back in the day, and I’ve always *wanted* to like it more than I actually do.

It’s interesting to speculate/opine about what’s wrong with the game. Meier himself says it’s because both parts (the strategic game and the mini-game where you spend 90% of the playing time) are both involving, and the mini-game takes too long to play; Meier has mentioned the example of why, when two units fight in Civilization, you don’t go into a full tactical battle that takes half an hour to play. However, the X-Com example you mention (where, I think, it works perfectly) contradict that, as do other games such as the Total War series, which *does* have 30-minute battles when armies meet.

Why do these work while CA doesn’t? My best guess would be that the X-Com missions and the Total War battles are more directly connected to what you’re doing in the strategic game. In X-Com, you’re investigating a UFO you just shot down, or fighting a terror attack that just happened; in Total War, it’s an army that you need to defeat. In Covert Action… it’s almost as if you’re breaking into a building just because it’s there. Yes, it might have a suspect or item you need to progress in the game, but other than that, every building feels like the same, has the same challenges, has information relevant to the case even it’s the “wrong” building, and so on. It’s just something you need to do several times per case in order to progress.

Also, I think, as a mini-game, it was done much better in Microprose’s Sword of the Samurai (where it was far shorter, more action-based, and, again, more related to what was happening, instead of feeling “generic.”)

I agree with you about the “this is obviously randomly generated” you get from the game, but I wouldn’t actually go all the way in the opposite direction (a couple of dozen hand-crafted cases). It should be possible, I think, to achieve the best of both worlds: better “pieces” of content, more variety, and more unpredictability (e.g.. on each situation, the bad guys might do different things, instead of following a set path; also, plot types might be separated into “early game”, “middle game” and “end game”, so that the player wouldn’t be thinking “yawn, I already did five cases just like this.”

Typo: “Sherlock Homes”. Also (from re-reading), there’s a “Mier” here. :)

Jimmy Maher

March 24, 2017 at 9:26 pm

Thanks!

Felix

March 24, 2017 at 3:47 pm

I have two pet examples of multi-genre games that illustrate the problem of mixing a good game blend. Dune (1991) for one is a real-time strategy game combined with a first-person adventure: you follow the storyline to gain new followers and powers with which to win at the strategic game so the story ends well. In other words, the two faces of the game support and complement each other (though I’m told much of the story can be skipped if you’re good at the strategy side and just want to make a speedrun).

On the other hand, Alien Legacy is an adventure game with a SimCity and shooter minigame thrown in for no good reason. And at least the shooter parts, based on the largely forgotten Star Raiders II (a favorite of mine, as it happens), work great. The strategy angle however is botched: I could never figure out how to make those little space colonies work at all, and without them you’re left hanging. Worse, the story is grand and elaborate enough that restarting the game if you get stuck feels like just too much trouble. So the whole thing falls flat, which is too bad because the story is awesome and I would have loved to see how it ends.

That said, I think RPGs are a bad example, because every single side quest in an RPG is based on the exact same mechanics as the bigger game. That those mechanics themselves consist of several minigames is less relevant, because 1) you play the same combination thereof to solve everything and 2) those mechanics can’t even work at all in isolation — each of them contributes part of an overarching experience. In a certain family of tabletop RPGs, mechanics are even used to build a frame for player-driven story building, so the two angles become not just inseparable but indistinguishable!

As for games being all about mechanics… oh dear, oh dear. Even in roguelikes, that revel in intricate clockworks of rules and formulae feeding off each other, a big part of the code is actually data: tables of monsters, weapons, spells, potions and other elements the game can recombine into something useful. And all the best examples also rely on prefabricated pieces to be inserted at key points into the game. As Fred Brooks Jr. famously said, “show me your code, and I still need to see your tables; show me your tables, and I don’t need to see your code”.

Regarding Mr. Crawford, with all due respect for his very real accomplishments, I suspect he never truly understood the point of stories. I remember exploring the question on my own blog — with your help — and failing to hit the mark myself. Stories, you see, need to be relevant: to have some sort of meaning for the audience. Some reason for the audience to give a damn about the characters and what happens to them. And in my experience, most people who try their hand at storytelling don’t get it. Many of them succeed anyway, simply by virtue of having a life they can draw from. A computer program however doesn’t; it’s just the proverbial million monkeys, banging away at their million typewriters. And it would take an infinite improbability drive for them to come up with another Hamlet.

Alex Freeman

April 12, 2017 at 11:56 pm

“In a certain family of tabletop RPGs, mechanics are even used to build a frame for player-driven story building, so the two angles become not just inseparable but indistinguishable!”

Which family of RPGs would that be?

Arne Babenhauserheide

June 28, 2023 at 10:26 pm

Examples for those are the “powered by the apocalypse” games. They turn Roleplaying into following fixed moves.

I think one reason why this can succeed is that the gaming group will fill in the gaps. At some point there is so much existing narration, that the narration takes over and the game follows the path previous gaming nights layed out, though unplanned.

EPG

March 24, 2017 at 3:54 pm

I also compared MicroProse’s enjoyable “Sword of the Samurai” to “Covert Action” in the last post before realising there would be a separate entry here, but now I realise the better comparison is between “Sword” and “Pirates!”. The former’s tactical games are more detailed (it’s physically stressful to wait in your castle as ninja appear), and the strategic game is more flimsy. It’s also possible that all these stories seem less silly when distant in time and space, and that people living in China or 2300 might not care about the differences between the Mafia and the Black Panthers.

Jubal

March 24, 2017 at 8:14 pm

I suppose ultimately, the thing that game creators need to remember is that process-heavy and data-heavy games are both valid approaches, just different ones, and the trick is to identify which works best with what you’re trying to achieve. Dwarf Fortress is a magnificent achievement in what it does, but it doesn’t mean that, say, Portal would be a better game if you could decide to just ignore GLaDOS and spend six months of real time building a Turing Machine instead.

On a related note – and I don’t mean to bash him too hard – I see Crawford states on his site that the next implementation of Storytron will likely leave out computer-controlled characters altogether and have them all run by players. Which seems to be missing the point somewhat, and leads to the unfortunate feeling that Crawford has spent three decades of his life and considerable sums of money just to reinvent the MUD.

Jimmy Maher

March 24, 2017 at 9:41 pm

A huge problem with Crawford’s approach, and one which I think he has consistently underestimated through all his decades of work on Storytron, is that of *communication* between the player and his interactive stories. We expect to be able to do that in language, but it’s very difficult to make a computer understand natural language, and if anything even harder to get it to output readable text from a pile of raw data. You can have the most compelling story in the world sitting in memory, but if you can’t *tell* it to the player what good does it do you? At least to some extent this problem might be conquerable with the benefit of modern developments in software engineering and modern hardware, but doing so would require great piles of cash — how much has Google poured into Google Translate by now, still with very imperfect results? — which Crawford doesn’t have. In lieu of being able to communicate in a natural way, he’s fallen back on arcane systems of symbols. The end results don’t have much resemblance to anything people think of when they think of a good story.

MB

March 24, 2017 at 8:43 pm

I think the player’s context factors in hevily… as 10-12 year old when I first played this game the procedural case generation issues didn’t really matter because I hadn’t developed a broad enough understanding of geopolitics and the like, and was more focused on the mini-games and individual missions. Sure, it has a bit of where in the world is carmen sandiego simplicity but still, as I’ve revisited the game more recently I think it holds up fairly well despite its short-comings. This is especially true when you compare it to the strict linear storylines of other “quest” type games of the same era. apple v oranges.

MB

March 24, 2017 at 10:57 pm

…also, this reminds me I have Covert Action installed on this machine. Might have to play a mission or two. Kind of difficult without a real keyboard though!

MB

April 7, 2017 at 6:28 pm

Good lord, global threat is outright impossible. Local is laughably easy. Played through National and Regional catching 6 masterminds without too much trouble. Switched to global for the last couple and now I remember why I quit playing this game as a kid — ha!

S. John Ross

March 24, 2017 at 8:59 pm

My long-standing observation, similar to the oatmeal quote, is “whenever they promise X billion to the trillion combinations, it always feels like five.”

I’m fascinated by the ludologist/narratologist thing, since both sound so unsatisfying to me and run contrary to my own ideals in design – and they do so pretty much equally.

In terms of games like this vs. games like Civilization, I have an easy answer for my own tastes, which is that Civilization is an instrument of creativity … As a Civ player, I’m not just being asked to solve a procedurally-generated problem; I’m given a paintbox and a canvas and I’m creating according to rules, and my creation is challenged by procedurally-generated problems. That layer, being invited to MAKE, is what brings me back to Civ (in virtually all its incarnations) time and again. Ultimately, it means that every civilization I create is, in fact, a piece of hand-crafted, non-procedural content for me to enjoy.

Jimmy Maher

March 25, 2017 at 7:41 am

You hit upon an interesting aspect of the ludologist/narratologist split, I think. Both agree that games are creative endeavors, but they tend to differ on where they place the most important source of creativity. Narratologists tend to take a more traditionalist approach, considering games to be authored works like books or movies; as with those other mediums, the creative force behind them is the designer. Ludologists see games as something entirely distinct from other forms, something which cannot be criticized using the same approaches. They place the creative emphasis on play itself, seeing the creators as the *players*.

As is not hard to discern from reading a few of my articles, I lean toward narratology in my own criticism and the types of games I mostly choose to criticize. But the reality in my view is that games taken as a whole are a little of both. So, while it’s hard to see something like Trinity as anything other than Brian Moriarty’s personal literary expression, your experience of Civilization is equally valid. And both games are in their own ways brilliant. I don’t care if people prefer one approach or the other. I only get annoyed when they start to say one approach or the other is *invalid*.

S. John Ross

March 27, 2017 at 5:42 pm

“You hit upon an interesting aspect of the ludologist/narratologist split, I think.”

Entirely accidental, I promise. My only intended comment on the ludologist/narratologist thing was (and remains) “they both sound awful.” I don’t think either sounds invalid.\

And I may just be misunderstanding the terms, but as described here, it sounds like “Game designers disagree on whether games should be miserably dull or wretchedly tedious.”

Felix

March 25, 2017 at 8:03 am

Which is exactly why No Man’s Sky disappointed so many people — a bullet the creators of Elite! dodged by trimming the many billions of possible galaxies down to just eight. And we should have known, because they did have the ability to offer players billions of galaxies at the time, even on limited 8-bit machines. Hardware wasn’t the issue. But nowadays many developers allow themselves to be blinded by all this computing power we no longer know what to do with.

See, procedurally generated worlds suffer from the same issue as procedurally generated stories: not so much that they’re monotonous — the real world can be, too, and better PCG techniques can alleviate the problem — but that they’re inconsequential. What, after all, make my own neighborhood inherently more interesting than any other in the city? Nothing, of course, except for the fact that I lived in it for 32 years and the experiences I had here shaped me in ways that other people might learn from. A computer-generated locale, no matter how intricate and plausible the simulation, simply won’t be anything to anybody.

At least Minecraft allows you to take ownership of those humongous worlds (or rather, tiny slices thereof) by changing them in ways that are uniquely yours. And sure enough, it’s one of the most successful games ever. If only people have gotten the point instead of mindlessly trying to clone the superficial aspects of the original.

But then we wouldn’t be having this discussion, would we now?

S. John Ross

March 27, 2017 at 5:47 pm

Yeah, that was what I meant with my Civ comment … if it consisted only of procedurally-generated stuff, I’d tune out immediately. But, like Minecraft, it makes room for the player to bring some personality to something that would otherwise lack it.

It sounds like Covert Action had no interest in authorship on either side of the monitor … that the designers didn’t feel compelled to create much, and also didn’t leave room for the player to.

G Ozen

July 2, 2017 at 4:22 am

Reverting the roles could turn Covert Action into a paintbox maybe? As a good spy, you have no option but to figure out the procedurally generated one unique solution. But the mastermind can use different groups in different ways to accomplish his goals. That even makes cooperation between hostile groups sensible as you would be forcing/persuading them (via mini games) to work together.

Jeff

July 31, 2025 at 11:29 am

Very good point here, I think you hit the nail on the head which many gamers are drawn to – a sense of creativity in the play itself. Civ is so satisfying because one can look back and feel happy with the outcome on the screen and feel justified in the input they made to get there. RRT also has this exact feeling of satisfaction.

Bernie

March 24, 2017 at 9:45 pm

Jimmy, great article. This one should go straight into the Hall Of Fame.

In support of your argument of why this game doesn’t work quite well, Activision did their own interpretation of the same spy-thriller concept with “Spycraft: the great game”. It was a fully story-driven collection of mini-games, some good, some average. It sure must have made Chris Crawford really mad at the time, since, as many titles from the era, it came on three CD’s full of Full-Motion-Video and photo-realistic backgrounds and props. As much as most of us have come to despise FMV nowadays, I remember actually having fun with Spycraft and getting sucked-in by the Clancy-esque plot. It was all done with solid production values and good writing. Microprose really went in the wrong direction and Meier was fully aware of the fact but, being a ludologist, drew his own strange conclusion about the length of the mini-games.

Regarding Crawford’s and Meier’s core arguments, if long mini-games are so toxic to game design, Why did SSI’s Gold Box series become so popular ? After all, some key battles (i.e. mini-games) could take hours and the main plot, very simple in its essence, was revealed through massive amounts of “fixed data” : maps, paragraphs, histories, static NPC’s, etc … , and we could say almost the same about Interplay’s Lord Of the Rings Trilogy, based on the most data-heavy works of fantasy in the history of literature.

Regarding “the divide” : for a successful example of a game designer striving for a perfect balance between process and story one should turn to Richard Garriott and his Ultima series, which have been addressed expertly by you in this blog. He started to tone down the “mechanical” aspects and flesh out a coherent fiction in III, managing a good balance and an engaging story in IV, and then went on to seek a more complex world model with V and VI with mixed results. As you pointed out in your post about it, V didn’t quite achieve Garriott’s ambitious goals for it -mainly due to him stubbornly clinging to the 8-bit platforms, in my opinion- but is perfectly balanced.

Finally, for me Ultima VI is a perfect example of everything you say in this post : its “process” side is as solid as can be for an RPG, even allowing the player to cook, repair weapons, etc … , the quintessential “sandbox” game, but its “story” side is also very impressive, with very detailed lore, NPC’s that are more like characters in a play and a complex plot that presents timeless issues in a very mature way, all of it dressed up in piles of gorgeous “data”. Nevertheless, almost everybody who has played it levels the same complaint at VI : its excessive characterization of the “Avatar” both during the intro and in-game breaks mimesis noticeably by not letting players cast themselves adequately in the lead role, only to “control” the protagonist. Maybe an extra disk full of portraits and garments and a sophisticated character creation sub-program would have been enough. Later RPG’s and even Remakes of Ultima V and VI offer this kind of thing.

Jimmy Maher

March 25, 2017 at 10:23 am

Ultima VI doesn’t quite get there for me, for reasons I’ll describe in a future article. (It feels rather stranded between the old way and the new, neither fully one nor the other.) Ultima VII, though, does everything you describe here to very good effect — even if that does include this increasingly strained and silly over-characterization of the Avatar.

Bernie

March 24, 2017 at 9:53 pm

That was a little too long, sorry ! (hope you and your readers don’t get bored halfway through)

EPG

March 24, 2017 at 10:51 pm

It’s odd that Crawford ships so much criticism and hate from text adventure hobbyists, when from outside they’re clearly on the same side, ranged against the overwhelmingly more popular types of simulation games that set you as the only thinking person in the world – “you are a soldier / a fast driver / a dictator”.

Felix

March 25, 2017 at 6:07 am

This is sadness, not hate. The man’s a genius. I consider The Art of Computer Game Design to be required reading for any aspiring developer. And what he’s done in recent decades remains important as fundamental research. Still can’t help but feel it was a waste of his talents, quixotically focusing for so long on a single aspect that, as it turns out, simply doesn’t work. And all because he insisted to hold onto the — admittedly widespread — misconception that any random chain of events barely connected to each other somehow counts as a story.

Jimmy Maher

March 25, 2017 at 9:59 am

I agree. I don’t think all that much of Crawford’s games as games. Most have been made as demonstrations of his theories, and have skipped the essential stage of the process which Sid Meier calls “finding the fun.” But his was a very important voice in getting game makers to take their craft seriously, and his ideas, even when I disagree with them, have always been provocative and eminently worthy of discussion. It’s been a shame to see him essentially remove himself from the discussion these past 25 years in favor of chasing his White Whale.

Jimmy Maher

March 25, 2017 at 7:43 am

Might have something to do with his habit of repeatedly calling out text adventures as a betrayal of their medium’s potential. ;)

matt w

March 25, 2017 at 12:02 am

If you play as Maxine, do you also score with progressively hotter secretaries? I suppose it wouldn’t be prohibitive to create twice as many secretary art assets, male and female–I remember 1990 and am guessing that a mainstream game wasn’t going to allow you to choose your sexual orientation. But it seems like, even more so than allowing you to play as a woman, it would be progressive for all the secretaries to be male. I’m imagining that you work your way up to Chris Hemsworth’s character from the remake of Ghostbusters.

Also, are the secretaries procedurally generated? Seems like something that could certainly be done today.

I may owe you a serious comment after this one.

MB

March 25, 2017 at 1:11 am

actually, yeah they’re dudes instead if you pick maxine — ha!

matt w

March 25, 2017 at 1:17 am

Are they still secretaries? I had thought that you were romancing secretaries in other organizations to get intelligence, but on further investigation it kind of looks like they’re from the pool at HQ at the end of every level–which is both more boring and somehow skeevier.

Brian Roy

March 25, 2017 at 4:55 am

Your overall ranking combined with mission ranking determines the “eye candy” at the end of each mission, if memory serves. And it’s just eye candy, with no bearing on the game. The office gives way to a hotel bar, and then a casino, and then the beach, I think. The eye candy characters are progressively more attractive, but I don’t remember them being procedurally generated the way in game characters are. I don’t personally remember associating any except the first with “secretary,” but one’s mileage may vary.

Jimmy Maher

March 25, 2017 at 7:48 am

I honestly didn’t know what happened if you played Maxine, so thanks for that. (Given the nature of games at the time, I kind of imagined you might get to join progressively better knitting clubs or something).

Nor, I’m embarrassed to say, am I at all certain that they’re all secretaries. Made some edits to that caption… okay, pretty much rewrote it. :)

matt w

March 25, 2017 at 5:23 pm

I was looking around and found this screenshot saying “The stories of a secret agent can only be gossiped to secretaries with a clearence [sic] level of AA or above.” Which makes it sound kind of like they are secretaries at least at the beginning… and could it be that the better you do in the game, the higher the clearance level required for the stories you have to tell, and it just so happens that the NPCs with higher clearance level are also more attractive? Probably not, but clearly someone is going to have to do a deep dive into the game to refresh our collective memory.

Having tried to find that again by searching for things like “covert action secretaries aa clearance,” I expect they’ll be coming to take me away any time now.

matt w

March 25, 2017 at 5:35 pm

For the record, this review has screenshots of a playthrough as Maxine, with a few of the eye candy guys… it’s the thought that counts, I guess. Blue-cardigan-over-black-turtleneck guy seems not to be an end of level reward but your actual secretary and in-game mechanic, Sam, who if you play as Maximilian is a woman with gold hoop earrings dressed in a tuxedo and black bowtie like a wedding bartender. I just don’t know, man.

David Boddie

March 25, 2017 at 12:17 am

That’s not a bad piece of box art, really. Certainly no worse than the one for Railroad Tycoon.

But “Max Remington”? I’m sure he must have been the master of close shaves in the spy world…

Pedro Timóteo

March 25, 2017 at 8:46 pm

He’s based on a real person, actually. For instance, he was the artist in Railroad Tycoon, and his picture appears with Meier’s and Shelley’s in one of that game’s title screens.

Lisa H.

March 25, 2017 at 9:45 pm

That link appears to be miscoded or something, because though it’s turning link color it doesn’t seem to actually be pointing to any address.

matt w

March 25, 2017 at 9:53 pm

I don’t know what Pedro was linking to, but here’s a mobygames page for Max Remington III.

Pedro Timóteo

March 25, 2017 at 11:25 pm

Hmm, I was sure I linked to that same URL… weird. Maybe I mistyped something. Thanks!

matt w

March 26, 2017 at 11:50 am

Yeah, sometimes this happens to me–I miss a quotation mark (I think that’s what does it) and I get link-colored text with no link. Glad that was what you meant!

Ricky Derocher

March 25, 2017 at 3:51 am

If you want to see bad box art – try the US release of “Lancelot” – http://www.mobygames.com/images/covers/l/90461-lancelot-commodore-64-front-cover.jpg

whomever

March 25, 2017 at 6:44 pm

OMG, that is absolutely hilarious.

Lisa H.

March 25, 2017 at 9:43 pm

I’m not familiar with the game, but that looks like deliberate parody to me. Inflatable stegosaurus (?), come on.

Ricky Derocher

March 30, 2017 at 2:05 am

The game itself is actually serious – one may think that it a parody by the US box art.

Here is the European box art for comparison:

http://www.mobygames.com/images/covers/l/256688-lancelot-commodore-64-front-cover.jpg

Lisa H.

March 30, 2017 at 2:58 am

Geez Louise. I don’t know what they were thinking misrepresenting the game like that, then. I mean, the art for Covert Action is certainly a touch cheesy, but at least seems reasonably in line with the tone of the game.

Jason Dyer

March 25, 2017 at 10:08 am

This is one of the best articles you’ve written.

ZUrlocker

March 25, 2017 at 2:55 pm

Agreed, this is a great posting. One of the best. Really interesting to get your analysis of Covert Action. I bought this game back in the 90s and found it rather lackluster and now I know why! I’m a big fan of espionage novels, movies etc, and Covert Action failed to deliver on those expectations. The minigames to me felt too arbitrary and removed from the story. I found Spycraft more compelling, but also somewhat long-winded. Anyways, great to give this genre it’s due.

Chris Ogilvie

March 26, 2017 at 7:33 am

I want to thank you for this article – it’s crystallized some thoughts I’ve had about games for some time that I’ve not been able to properly express until now.

For years, I’ve found certain strategy games that I otherwise love to be somehow… lacking. Especially in the end-game. I’m talking about games like Master of Orion II or, fittingly enough, games from the Civilization series. I enjoy them well enough, but I always have an itch at the back of my head somehow wanting something more. And I’ve never been able to figure out just *what* that something would be.

But now I think I’ve nailed it.

Take MoO II for example. Playing it, I know I would often want more of a sense of exploring and settling the galaxy, of the politics of managing an interstellar empire, and of dealing with alien races in a meaningful way. And the game itself never really provided those things. In the end, it always came down to manipulating game elements and systems, rather than providing me the *experience* that I was hoping for.

I’ve known for years that I’m 100% an experiential gamer. So much so that I often find myself thinking “This game would be so much better of they stripped the gameplay out of it.” But I’d never made the link between that preference of mine and the deficiency (to me, anyway) in certain strategy games. Until just now.

It seems to me that, like Covert Action, my problem with games like MoO II is that they have a great many procedural elements and lack a hand-crafted narrative. It’s all ludology (and, in the case of Civ or MoO, *brilliant* ludology) and no narrative. And narrative is what would provide the subjective experience that I want out of the games.

Which means that what I *want* is MoO II, but with carefully-crafted narratives that support the *experience* of settling and managing a galactic empire. Instead, what I get is 10,000 unique galaxies to play in… each one of which is a perfectly serviceable, and nearly indistinguishable, bowl of oatmeal.

So, again, *thank you* for this article. It’s been years that I’ve not been able to figure out just what I found lacking in these sorts of games. Being able to put my finger on it, finally, is like being able to scratch an awful, persistent itch.

Jimmy Maher

March 26, 2017 at 8:42 am

If you haven’t played them, you might want to look at the original X-Com and Alpha Centauri sometime. Both make an effort to inject some narrative elements into their grand strategy. Feel free to report back at some time in the future if you do get a chance to play them. ;)

Chris Ogilvie

March 26, 2017 at 5:20 pm

Ah, Alpha Centauri has been a favourite of mine since it came out. Probably for exactly the reason you mention. There’s such a sense of history and world there… it’s wonderful. Brian Reynolds seems to have been exactly on my wavelength.

Have to give X-Com a go, though…

xxx

March 27, 2017 at 5:58 am

X-Com is really the refutation to Meier’s theories about game development. It’s two separate games woven into a coherent whole, with your actions in each having significant repercussions in the other. They’re each quite complex, much too much so to be called “mini-games”, and neither would be as much fun without the other to give it context. It is absolutely not the case that “one good game is better than two great games”, in X-Com’s case — they’re a perfect symbiosis.

Narratively, it’s also head and shoulders above games like Civilization or Railroad Tycoon. It’s not a wide-open sandbox — there’s a very specific story it’s telling, you have a goal and a well-defined endgame, there are timed events that lead up to that endgame, and once you get there it’s enormously satisfying. The specifics very from playthrough to playthrough, but the story is always the same. (Rather the opposite of what Covert Action attempted to do, where it tries to tell a variety of stories, but they all end up feeling bland and samey.)

Definitely give it a go. Really looking forward to when this blog gets up to X-Com!

Mike Taylor

October 2, 2018 at 5:51 pm

So much so that I often find myself thinking “This game would be so much better of they stripped the gameplay out of it.”

Yes!

I found exactly this when trying, at my sons’ insistence, to play Mass Effect, which apparently has an excellent story. I was just so irritated by the need to play through the tedious combat stuff before I could get back to the story, that in the end I stalled out completely.

Yeechang Lee

March 26, 2017 at 12:10 pm

Jimmy, now that we’re rapidly approaching on Civilization, it would be great if you could look into why Computer Gaming World never published a review of the game!

Jimmy Maher

March 26, 2017 at 12:38 pm

They did publish an extended preview of the game, based on a late build. Probably didn’t think there was much a formal review could add. They did later publish a couple of strategy articles and awarded it Game of the Year, plus Allan Emrich and Johnny Wilson’s classic book Civilization or Rome on 640 K a Day. So it certainly got plenty of coverage.

Stephen Norris

March 26, 2017 at 10:48 pm

Type – “never set well” should be “never sat well”.

Jimmy Maher

March 27, 2017 at 7:26 am

“Sat” and “set” still get me every time. Thanks!

_RGTech

April 12, 2025 at 6:03 pm

“, it’s seems equally clear that”

…this would read better without the ‘s.

Jimmy Maher

April 13, 2025 at 2:32 pm

Thanks!

Captain Rufus

March 27, 2017 at 7:52 am

Thanks to this article it sent me to EBay looking for Murder on the Zinderneuf. Thanks to related tines I just dropped 38 bucks on old album boxed EA Atari 800 games. Good job!

But as to some of the article? Yeah eff procedurally generated style games. Roguelike is to RPGs what REAL TIME is to Strategy games. I know instantly it’s pretty much not for me. Instead of a well crafted dungeon it’s a pointless mire that really is like all the other ones. It gets even worse in something like Dungeon Hack which I reviewed for Felipepe’s RPG book on RPGCodex. They are just boring and generic slogs made worse given the AdnD ruleset and it being a single player game. (Then compare the masterfully created dungeons in Legend of Grimrock which are some of the best RPG puzzles ever. Because I feel dumb when I can’t figure one out and then seeing a solution just shows me it was my fault and not the designers going FULL SIERRA on me.)

The oatmeal analogy is the most perfect explanation as to why procedural generation games kind of suck.

As to games with multiple elements? Eh.. Depends on the game and the quality. Master of Orion 2 is a decent 4x but I am mostly there for the ship to ship combat. In fact all the more modern 4xs without tactical combat don’t grab me. But if Moo2’s over mode wasn’t good all the tactical crunch in the world wouldn’t matter. I’m sure some folks feel the opposite in the game’s modes.

Like a good sandwich even if you are merely there for the meat you need good condiments and bread. Otherwise it doesn’t work. This is also why I dislike Ultima 7 in spite of it being a technical achievement. Combat and inventory management and exploration are completely terrible to me and no amount of story and world simulation can fix it for me. I’d rather see it demade into U5’s computer version where the story also has a good game to go with it. The graphics and world realism don’t much grab me when I can’t enjoy the combat and I have to micromanage a party of constantly hungry babies whining for food while I have to manage one of the worst inventory systems in a game. Whereas 5 has proper turn based combat, party food and inventories as a number and a universal list in text plus exploration is made better with locations being a separate thing to the overworld which actually makes it feel like a world and not a small island with little communities in it. (6 also has these issues but turn based combat helps a bit, and Nuvie or the SNES port fixes the viewing window. It too would still be better in the U5 engine. I’m not sure anything is saving 8 and 9 however..)

Meredith Dixon

March 27, 2017 at 9:33 am

I’ve been playing Covert Action since it came out. I’ve won the game (I consider “winning” to be catching all 26 masterminds) at least three times, and I’ve played many, many more partial games over the years. I couldn’t have done that with any enjoyment if it had had hand-crafted plots. (One big disappointment of Covert Action, by the way, is that, just as in High Seas Trader a few years later, it’s obvious that the dev team never really expected you to finish the game. The only reward for winning is a small text box announcing that you have captured all 26 masterminds, or, in the case of HST, restored your family fortunes.)

I think the game failed, to the extent that it did, because so many of the minigames are unnecessary and even counterproductive. When I’m playing seriously (with an intent to solve cases and win), the only mini-games I ever play are wiretapping, car bugging (which is just a form of wiretapping with a stricter time limit) and invasion. Cryptography is fun in itself but it takes far too long (in game time) for far too little information gleaned. I’ve never been any good at the car chase, and car bugging accomplishes everything it does, much more easily.

I’ve always played as Maxine, and, no, the men aren’t obviously secretaries. A Maxis employee I once e-mailed about the game claimed that they were portraits of people who worked at Maxis; if he was telling the truth, he probably meant the office scene; the beach scene hunks look like Marvel superheroes in unconvincing civvies to me, and the four glamorous guys at the casino are definitely movie stars. (Specific superheroes, I mean, and specific movie stars).

David Ainsworth

March 28, 2017 at 3:54 am

The key problem, from my perspective, is that all the suspects and groups and masterminds are entirely interchangeable. What’s worse, they have no characterization or personality.

X-Com builds itself upon the distinct kinds of enemies you encounter. Alpha Centauri designs factions around characterization, then adds all the tech quotations to build a stronger and stronger sense of the characters, making you care about them, whether it’s to shut Yang up or give Lal a hand. Civilization uses the short-hand of history to partially develop its leaders, but in-game behavior drives your impressions of Montezuma or Gandi to such an extent that the designers opted to duplicate the Gandi nuclear weapons bug in sequels because it was central to player impressions of him.

Compare to Beyond Earth, whose faction leaders are essentially generic faces, or to Covert Action, which ought to be chock full of heels and villains but which can’t muster even one foe as compelling as Carmen Sandiego. You’re up against Random McFakename, who has random facial features and pursues a random sequence of plots until tracked down and caught. The game manual provides brief information about each group of interest, but in-game they are entirely interchangeable: the Mafia is no different from the Stassi in functional terms. Undifferentiated = no characterization.

Worse, your only foes when breaking into a hideout are faceless goons differentiated from group to group only by turtleneck color. They’re all equipped the same way. And the villains you’re tracking are all interchangeable on the tactical layer. That hacker you broke in to capture? Sitting in a chair. That expert assassin? Also just sitting in a chair.

Even a few small changes would make a big difference: have specific groups allied or opposed to other groups. Red September is a splinter group from the PFO, so maybe they hate each other. Have each group’s mastermind have a specific agenda and generate missions relating to plans advancing that agenda: even if the agendas repeat between or within games, working out which one is at play might help you steal a march on the enemy in a way that makes sense within the fiction, rather than being a pure metagame consideration. (One terrorist group plotting attacks in Columbia may proceed in similar ways to another plotting attacks in Israel.)

Even better, reduce the number of masterminds in a given game and determine the ones you’re up against based upon difficulty. State supported groups like the Revolutionary Guard would be foes at higher levels, with better equipped troops and more double-agents within your organization. On the easiest level, some of the tougher organizations might even help out with information or other support in order to use you to eliminate their rivals. Then run the grand campaign as a string of increasing difficulty levels: for example, the Mafia helps you block a plot by the Amazon Cartel to open a bigger market for their drugs in the US early on in exchange for a piece of information which gives you a hint about their agenda when you finally go up against them later in the campaign. That kind of campaign would also make your double-agents more useful, especially if you pull off a coup and get a minor mastermind as your double-agent.

Mike

March 29, 2017 at 9:17 pm

“We could, for instance, look to the many modern CRPGs which include “sub-quests” that can absorb many hours of the player’s time, to no detriment to the player’s experience as a whole, at least if said players’ own reports are to be believed.”

From this RPG player’s perspective, CRPGs certainly do suffer from the straitjacket of the current formula (endless sub-quests while having no actual time pressure for the main quest, combined with allowing the player to make his “own” moral choices and skill improvement path choices, while preventing no-win situations from occurring down the line).

You often really don’t remember what was the main thing you were trying to accomplish. So you get quest journals, minimaps with symbols denoting “special” places, and so on. It all gets a bit pointless after a while, and makes it more and more difficult to appreciate the game world when you have go through the same kind of mechanical miniquests that you have done a zillion times before in another game – because if you skip the side quests, you will miss out on the needed levels, skills and items to proceed in the main quest.

This is the true legacy of Baldur’s Gate and Monkey Island? Bleh.

Max

April 18, 2017 at 12:34 pm

The specific problems you’ve pointed out can be fixed pretty easy without ripping out the generative component. Mafia can be marked as not working with ISIS, etc. The problem with generated text is solved by removing the specific texts and leaving the vague descriptions like “The decoded message states that the Mafia wants to acquire the floor plan blueprints for the US embassy.” Procedural generation works best when the text is sketchy enough so that the reader does not have any problematic generated details to fixate upon. IMHO the whole idea of generating prose is as intrinsically flawed as generating animation, music or art – humans are not robots and will discern formulas very easily after a couple of tries.

The solution you propose – “just throw some content creators on it, folks” was a cop out for game designers back then when the budgets were lower and game designers had more freedom to pursue what they wanted. That solution is also much more predictable and calculable and that’s why it dominates the modern gaming with its huge budgets and development teams.

himitsu

April 28, 2017 at 10:41 pm

I don’t think that procedural generation is a problem, but that badly crafted games are a problem, and you cannot escape that with handcrafting. I think it is enough if we look at the Mass Effect series and its downfall to understand that.

Tom

May 2, 2017 at 9:13 pm

Out of curiosity, what do you mean by “the Mass Effect series and its downfall”? I have my own criticisms of the progression of the original trilogy, but “downfall” seems a bit hyperbolic.

himitsu

May 12, 2017 at 8:47 pm

I wanted to share my opinion, but EA acted faster:

https://www.polygon.com/2017/5/10/15616726/bioware-montreal-restructuring-mass-effect-on-hold.

“At least some of the team at BioWare Montreal, the studio behind Mass Effect: Andromeda, is being retasked to other projects. Kotaku reports, citing anonymous sources, that the studio is being “scaled down” and that the Mass Effect franchise is going on “hiatus.” Reached for comment, studio director Yanick Roy spun things somewhat differently.”

Tom

May 18, 2017 at 3:56 pm

That’s…unfortunate. I was looking forward to seeing where they would go with Mass Effect Andromeda.

What do you think the problems were, just out of curiosity?

Johannes Paulsen

May 18, 2017 at 1:53 pm

Jimmy,

An interesting article, but I disagree with you, and instead believe that Sid Meier was correct in his analysis of the Covert Action problem.

The examples you put forth (CRPG sub-quests and XCom) don’t hold water. First off, I don’t think that many CRPG players really care much about the actual story. IMHO, most modern CRPG players are there PRIMARILY for the combat and exploration, and the storyline is just a rationalization for that activity. The game mechanics drive the story, not vice-versa. Since a typical subquest just lets the players go off and do more exploration and fighting, it’s essentially just one more goal to complete. Heck, take a look at Dragon Age — other than the fact that there’s fewer cutscenes, the subquests largely involve almost identical actions to any other ‘main storyline’ mission.

Because of that, there really isn’t anything for the player to forget. She’s focused on moving to the next goal and fighting the next enemy, most of which are pretty much the same as everything else, just with bigger weapons and stronger enemies as the game progresses. The arrows point her to the next thing to do. Reminders pop up if she’s on a timed mission.

Covert Action asked the player to keep track of a bunch of stuff that is no more or less memorable than anything in a modern CRPG story (for the life of me, I can’t actually remember at this moment who/what the big bad enemy in Dragon Age: Inquisition was despite putting 100 hours into a completionist play through when it came out.) The problem was that the subgames involved different skills and different tasks (car chase! Decryption! Breaking and entering! Wiretapping! Review background file for more information!) over an extended period of time (ten minutes is an eternity in video games if I only have an hour to play for a given session.) Worse, it didn’t have any of the little reminders that modern RPGs have.

(Regarding XCOM, I did not play the original, but did play the relatively recent remake, and found that the strategy aspect complemented the main game and, more importantly, didn’t take up that much time vs. the combat.)

I think a much better point of comparison is ALPHA PROTOCOL…which was a remarkably similar espionage RPG that had minigames. But it differed from COVERT ACTION by having those minigames appear while the player was in the functional equivalent of the breaking and entering mission, as opposed to while at the mission hub. (It was an underappreciated game with a good story that actually could change significantly depending on player choices….and failed for reasons completely different than COVERT ACTION.)

DerKastellan

June 1, 2020 at 11:32 am

There’s some truth to what you say. Having spent hundreds of hours in “The Witcher 3” lately it is hard to not notice how repetitive the game is. This might actually bother me in areas like Novigrad that are heavier on missions – which made me quit the game after having played it like an addict before. But it didn’t bother me when I was exploring the countryside, figuring out which encounters I could already beat and which not, exploring, clearing the question marks off the map.