Anyone who has followed the career of the British game developer Chris Sawyer down through the years knows that he prefers to go his own way. This was true from the very beginning.

In 1980, when Sawyer was fourteen years old, Sinclair Research subcontracted out the manufacture of the ZX80 — the cheap microcomputer that was about to take all of Britain by storm — to the Timex plant located in his hometown of Dundee, Scotland. From that moment on, Dundee was a Sinclair town. And small wonder: by 1983, with the cheap and cheerful Sinclair Spectrum pushing Britain toward the status of the most computer-mad nation on earth on a per-capita basis, the house that Uncle Clive built had become a significant part of the city’s economy. Half of the Dundee kids who were interested in computers seemed to have gotten jobs at the Timex plant, while the other half had just gotten Speccys for their living rooms.

Sawyer was no less fascinated with computers than his peers, but he was also a dyed-in-the-wool iconoclast. Just as the Spectrum boom was nearing its peak, he saved up his money to buy… a Camputers Lynx, one of those oddball also-rans of the 1980s which are remembered only by collectors today. And when it became clear that this first computer of his was destined for orphandom, he chose to invest in a Memotech MTX, another doomed machine.

His strange taste in hardware proved a blessing in disguise. With very little software available for the likes of a Lynx or MTX, Sawyer was forced to learn how to make his own fun, forced to become a programmer of games rather than a mere player of them. He would read about a game for another, more popular platform in a magazine, look carefully at the screenshots thereof, and make his own version that played as he imagined the original must.

One day in 1984, Sawyer’s chemistry teacher called him aside. Knowing that his student liked to program, the teacher showed him a newspaper article he had clipped out, telling how another local boy had made £1000 selling his games. Sawyer was inspired. By the time he moved to Glasgow to attend university in the fall of that year, he had made contact with Memotech themselves, who were eager for software of any stripe for their struggling machine. Absolutely no one — least of all the soon-to-be-bankrupt Memotech — got rich off the MTX, but Sawyer did make enough money to buy a printer and floppy-disk drive.

Even after Memotech bit the dust, he continued to go his own way as stubbornly as ever. Instead of a Commodore Amiga or Atari ST like his friends were buying, he scraped together the last of his Memotech earnings to buy an Amstrad MS-DOS machine, another definite minority taste at the time among gamers in Britain.

Once again, though, the road less traveled proved advantageous. In need of a job just after graduating from university, he contacted Jacqui Lyons, a former literary agent who had made a spectacular debut as Britain’s first ever software agent when she auctioned off to the highest bidder the porting rights to Ian Bell and David Braben’s game Elite, a sensation on the BBC Micro that went on to become the British game of its decade, thanks not least to her efforts. Now, Sawyer learned from her that the British industry had need for MS-DOS specialists — not so much for the domestic or even continental European market, but in order to bring its games to American shores, where MS-DOS was fast becoming the biggest platform of them all. Thus Lyons gave Sawyer a contract to port StarRay, an enhanced version of the old arcade classic Defender, from the Amiga to MS-DOS (the end result would be published in the United States as Revenge of Defender). When that went well, he was entrusted with the MS-DOS port of Virus, the long-awaited second game from David Braben himself.

Sawyer spent the next five years doing yet more ports. He worked alone from his Scottish home, evincing already the reclusive tendencies that would eventually get him labelled one of gaming’s greatest “enigmas,” whilst building a reputation for speed and efficiency that would also never desert him. He was arguably better versed in the tricky art of Intel assembly language than any other person in the British games industry; he refused to write in a high-level language, a resolve he has stayed true to to this day. “I enjoyed the work and it paid well,” he remembers, “though I became very frustrated that often I was unable to finish a contract because I’d caught up with the original game’s programmer and had to wait for him before I could convert the remainder of the game. My solution was to take on two conversions at the same time.” He developed a particularly good relationship with Braben, becoming the only programmer besides himself to which the latter was willing to entrust the hallowed name of Elite. In 1991, Sawyer coded Elite Plus, an enhanced version of the game for the latest MS-DOS machines; he then ported Frontier: Elite II, its belated, ambitious, and ultimately underwhelming sequel, to MS-DOS in 1993.

Up to this point, Chris Sawyer had been widely and fairly judged as a technician rather than a creative force. The teenager who had cloned games he had never actually seen from magazine reviews seemed every bit the father of the man who still earned his living by making other people’s games look and play as well as possible on alternative hardware. But now came the great leap that would elevate his name into the firmament where lived the superstars of British game development — names like David Braben, Peter Molyneux, and David Jones (another product of the tech-obsessed city of Dundee, as it happened). Sawyer may have been a late arrival, but in the final reckoning he would outshine all of them in terms of the sheer quantity of pounds his games brought in.

As so often happens when you look closely at such things, Sawyer’s inexplicable dizzying leap into original game design is perhaps less inexplicable or dizzying than it first appears. Certainly his first masterstroke wasn’t made from whole cloth. It sprouted rather from the fertile soil of Railroad Tycoon from MicroProse Software, Sid Meier’s brilliant 1990 game of railroad logistics and Gilded Age financial warfare. Sawyer:

I was fascinated with Sid Meier’s Railroad Tycoon game. I played it for hours and hours; it was definitely my favorite game at the time. The viewpoint was just an overhead 2D map, though, and I wondered whether [an] isometric viewpoint would be better, and if other modes of transport should be included. I was inspired.

So, while he was waiting for his better-known colleagues to send him the next chunks of their own games for conversion to MS-DOS, Sawyer began to tinker. By the time Elite II was wrapping up, he had an ugly but working demo of an enhanced version of Railroad Tycoon which did indeed shift the viewpoint from vertically overhead to isometric. “I decided to devote all my time to the game for a few months and see what developed,” he says. He convinced a talented free-lance artist named Simon Foster, who was already an established name in commercial graphics but was looking to break into games, to provide illustrations, even as he made the bold decision to step up to cutting-edge SVGA graphics, at more than twice the resolution of standard VGA. At the end of that few months, he was more convinced than ever that he had a winner on his hands: “Even people who didn’t normally play computer games would sit for hours on end, totally engrossed in building railway lines, routing trains, and making as much profit as possible.” He soon made his train simulator into an all-encompassing transportation simulator, adding trucks and buses, ships and ferries, airplanes and even helicopters.

The choice of publisher was obvious. Jacqui Lyons connected him with MicroProse’s British office, who immediately saw the potential for marketing the game as a pseudo-sequel to Railroad Tycoon; thus it was agreed that it would be known as Transport Tycoon. It shipped under that name in Europe and North America in time for the Christmas of 1994. And just like that, Chris Sawyer’s days of toiling as an anonymous porter were behind him, as he took his place among the stars. His elevation was richly deserved based on his game’s surface qualities alone.

Indeed, its groundbreaking interface is as good a place as any to begin to sing Transport Tycoon‘s praises. Any long-running, in-depth historical project such as this one of mine winds up becoming a form of time travel for its propagator, who comes to live a part of his life in the past which he studies. The fact is, I just don’t have much time to play modern games that aren’t on the syllabus. My near-complete immersion in ludic antiquity means that I get some sense of how these old games must have looked to the people who saw them for the first time. When I fired up Transport Tycoon after years of playing VGA games sporting interfaces that were technically mouse-driven but still lacking most of the flexibility we’ve come to expect from a modern GUI, my jaw dropped to the proverbial floor. Transport Tycoon plays, looks, and even sounds completely different from any of its peers of 1994.

Transport Tycoon

But no need to take my word for it: Julian Gollop, the mind behind the iconic X-Com series, happened to visit MicroProse while the folks there were playing around with a pre-release version of Transport Tycoon. He describes it as looking “awesomely sophisticated” in comparison to anything else on the market: “Especially the interface, because he [Sawyer] had essentially programmed his own Windows-style interface on top of DOS, which in itself must have been quite a lot of effort, let alone making the actual game. The X-Com interface was incredibly primitive by comparison.”

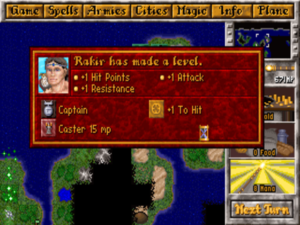

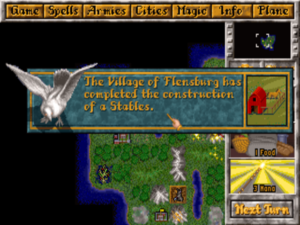

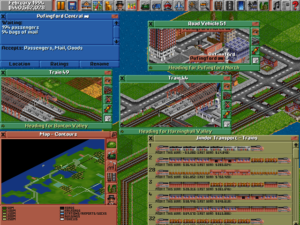

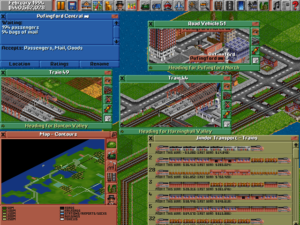

Windows, windows everywhere. All of them are dynamically updated in real time, all of them are interactive, and all of them can be dragged where you will.

As Gollop notes, Transport Tycoon‘s interface is built around windows which you can open and close whenever you wish and drag around the screen to wherever you want them. All of these windows are updated in real time. If you bring up a view of a vehicle, you see it going about its business there in its window, moving through the same world that fills the screen behind it. Bring up ten vehicles, and you can watch all of them at once with a little judicious clicking and dragging. Click on a certain icon in any of those windows, and the main view jumps to the location of that vehicle. In the context of its time, all of this is absolutely stunning.

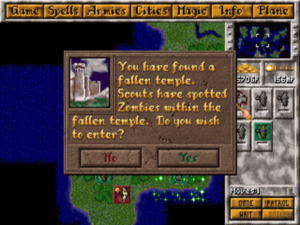

But we should step back now and cover the basics. Transport Tycoon presents 100 years of shipping — by railroad, by road, by sea, and by air — stretching from 1930 until 2030. It plays in real time, but is nevertheless a sedately paced, even relaxing affair on the whole. You begin with a modest bank loan and a map full of cities, factories, and natural resources craving connection, and go from there. Up to seven computer opponents can join you, or you can play with another human via a modem link-up, but competition isn’t the real heart of the game’s appeal. No, the core appeal — the thing that will bring you back to it over and over — is laying out your transportation network as efficiently as possible, then sitting back to watch it in action. You need to raise and lower land at times, build tunnels and bridges at others. You need to see to the signals on your railroad to ensure that traffic moves briskly but safely. And of course you need to purchase the vehicles themselves and assign them their routes. It’s almost indescribably satisfying to watch your network in action, just as it’s almost impossible to resist tweaking it constantly to squeeze that much more efficiency out of it. Transport Tycoon is a software toy of the highest order, as well as a series of endlessly intriguing spatial puzzles. (How can I get from Point A to Point B most effectively when I’ve already built all this other stuff in between?)

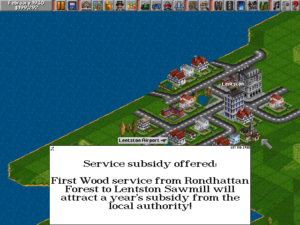

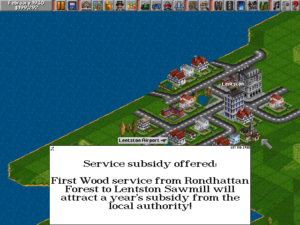

As with Railroad Tycoon, the economy of the world in Transport Tycoon is to at least some extent linked to your actions as a transportation mogul. And also as in Railroad Tycoon, subsidies will occasionally pop up to bring attention to under-served places. (These windows too are interactive. Clicking them once brings you to the first location mentioned; twice brings you to the second. The interface never ceases to amaze.) Hardcore puzzlers can take the subsidies as challenges; these places have often remained unlinked because getting between them is hard for one reason or another.

For all the obvious and acknowledged inspiration of Railroad Tycoon, Transport Tycoon gradually reveals a very different personality. Whereas Sid Meier’s game is at least as much a cutthroat business simulation as a model-railroad set, Chris Sawyer’s really is all about its busy little vehicles, lacking the stock trading of the earlier game or even its rate wars. Here you compete with your opponents for the choicest spots on which to build stations and terminals, and try to serve your mutual customers better so as to win more of their business, but none of it ever feels quite so life-or-death. This is a much more easygoing experience.

Unlike Railroad Tycoon with its maps based on different regions of the real world, Transport Tycoon takes place in a landscape of the imagination — more specifically, the computer’s imagination; each new map is randomly generated. This makes its relationship to real history that much more attenuated. Although its timeline covers some decidedly fraught decades in our world, wars are never fought in its, and crises of any stripe are unheard of. Big-picture circumstances never change at all beyond more and more people needing to haul both themselves and more and more of their stuff from place to place.

Pleasantness is an underrated quality in games, as it perhaps is in people, but it’s one that Transport Tycoon has in spades. After a long stressful day, watching this bustling but orderly little world is a nice way to unwind, even if you’re not actually doing all that much. This was by design; Sawyer says that he consciously created “something that was fun to watch as well as rewarding to play.” Simon Foster’s graphics are the perfect compromise between clarity and detail. Nothing is static; everything in the environment, not just the vehicles that drive through it, is moving, changing, developing. Buildings go up before your eyes, towns expand, crops appear and then disappear on the farms as you haul them away, forests grow and are cut and grow again. Meanwhile John Broomhall, MicroProse’s long-serving in-house composer, outdoes himself with a jazzy soundtrack that screams mid-century Americana. Despite the game’s British origins, the whole experience evokes that time of boundless American optimism and prosperity before the costs of Progress became clear, back when better living and heavy industry were synonymous. It’s a soothing balm to our current disillusioned, pandemic-addled souls.

Then again, Transport Tycoon needs every ounce of good will it can generate — because, taken purely as a piece of zero-sum game design, it’s horribly, hopelessly broken. Pretty much none of the mechanisms that surround the core simulation engine — the things that ostensibly make Transport Tycoon into a proper game rather than just a software toy — work properly.

The drawn-out length of the thing is a good starting point for a discussion of its flaws. Transport Tycoon runs at only one speed; there is no fast-forward function. By my calculation, playing through the full 100 years would take you somewhere north of 30 hours if you never paused it at all in order to plan your construction projects. This is problematic in itself; some other, shorter options for playing a complete game would hardly have gone amiss. Yet it’s made worse because the rest of the game just isn’t set up to support such an extended length.

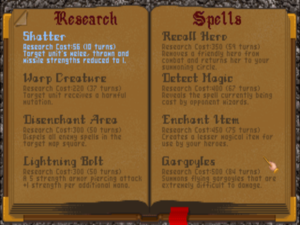

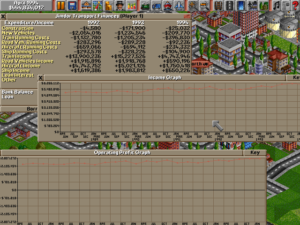

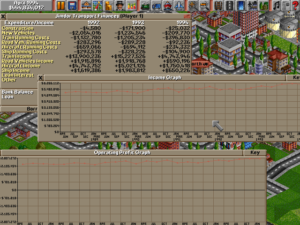

There’s a limit of 40 trains, 80 road vehicles, 50 ships, and 80 airplanes in the game. If you’re expanding with any degree of energy whatsoever, you’ll begin to hit those limits before you’re a third of the way in. After this, all you can do is optimize to take advantage of the newer vehicles which allow you to haul more stuff more quickly. But there’s nothing that compels you to do so beyond the siren song of your inner perfectionist because the economy is completely broken. Your finances might be mildly challenged during the first few years of a game of Transport Tycoon, especially if you choose the Hard difficulty level, but after that you have all the money in the world; you couldn’t go bankrupt if you tried.

This effectively infinite bankroll makes cost-benefit analysis meaningless, causing what ought to be interesting dilemmas — the meat of a good strategy game — to become moot. Consider: you need to run a railroad line over some very uneven terrain in order to connect a farm to a factory. In theory, you should be forced to balance the delays caused by steep grades on a track against the considerable cost of raising and lowering land to avoid them. In practice, though, you need do no such thing: money is flowing like water, so you just flatten out the land without giving it a second thought. Or: you need to choose which locomotive to employ for a vital but short jaunt between two neighboring cities. In theory, you should contemplate whether buying the latest 120-mile-per-hour silver streak of an engine is really worth the money on a local commuter route like this one, where the train will spend as much time loading and unloading in the station as traveling. In practice, though, you just buy the silver streak, because why not? What else are you going to do with your money?

Transport Tycoon likes to present itself as a hardcore business simulation. Don’t believe it for a second.

And as for the competition… oh, my. Your computer opponents succeed only in annoying the heck out of you with their epic stupidity; they’re forever building absurd Gordian knots of roads and rails that go absolutely nowhere, inadvertently blocking you from reaching the places that you actually need to get to. Building your way around their mess is a challenge of a sort, to be sure, but not a very satisfying one in that it demolishes any semblance of the clean, efficient networks that are such a pleasure to watch in action. Like a lot of players, I usually just turn the computer opponents off completely so I can concentrate on my own logistical works of art. The only way to get a really enjoyable competitive game out of Transport Tycoon is presumably to connect two computers, each with a real human behind the screen. (Unfortunately, I was never able to test that side of the game myself, as getting such a link-up working in DOSBox today is a tall order indeed.)

The artificial “intelligence” of your computer opponents provides the most vivid demonstration this side of a populist politician of what happens when extreme ambition collides with extreme incompetence. Its stupidity has become so legendary that at least one web page is devoted to showcasing the best or worst — depending on how you look at it — of its roads to nowhere.

Beginning about twenty years in, maintenance begins to annoy you even more than the computer players. Every vehicle in the game has a service life which, once exceeded, results in a constant stream of schedule-destroying breakdowns. It’s an interesting mechanic in theory, but utter tedium in practice. When you get a message that a vehicle is getting old, you have to manually send it to the nearest depot, wait for it to arrive, and then manually replace it with a newer version. There’s nothing fun or challenging about doing so; nor, what with all the money you’ve banked by this point, are there any financial concerns to balance. It’s just pure busywork. Not coincidentally, it’s right when vehicles start to age out of service that I tend to bail on most of my games of Transport Tycoon — and, if anecdotal evidence is any guide, I’m far from alone in that. If you become one of the few to persevere, however, you’ll eventually reach the late stages, where you get to contemplate manually pulling up all of your railroad tracks to replace them with monorail tracks. This is exactly as much fun as it sounds like it would be.

The end of a century of Transport Tycoon — a screen shockingly few players ever see.

Recluse that he is, Chris Sawyer has given very few in-depth interviews over the course of his career. He did, however, talk with Retro Gamer magazine at some length in 2015. I was particularly intrigued by one thing he said there, in response to a question about how much input MicroProse had in shaping the finished Transport Tycoon: “I think they did suggest some changes, but few made it into the game — either it wasn’t possible to do what they wanted or I was too stubborn!” I do have to wonder if those rejected suggestions might have fixed some of the game’s obvious, fundamental issues. But then again, the all-important Christmas deadline was just as likely the real determiner. MicroProse was one of the publishers most prone to releasing games before their time, and Transport Tycoon actually reached stores in far better shape than many of their other games.

A game with as many fundamental design issues as this one has shouldn’t be recommendable. And yet I find Transport Tycoon impossible not to like, much less to hate. The presentation is just so slick and charming, and building out your transportation infrastructure is just so soothing and satisfying, that the game transcends its faults for me, blows a hole through all of the critical facilities which tell me that a game needs to succeed as a whole to receive the label of classic. In fact, it leaves me in what feels perilously close to an ethical dilemma, as my critic’s brain wrestles with my player’s heart. The closest point of comparison I can offer is a game that is as different as can be from Transport Tycoon in most other ways: the CRPG Ultima VII. Please bear with me while I engage in the supreme arrogance of quoting myself:

Classic games, it seems to me, can be plotted on a continuum between two archetypes. At one pole are the games which do everything right — those whose designers, faced with a multitude of small and large choices, have made the right choice every time. Ultima Underworld, the spinoff game which Origin released just two weeks before Ultima VII, is one of these.

The other archetypal classic game is much rarer: the game whose designers have made a lot of really problematic choices, to the point that certain parts of it may be flat-out broken, but which nevertheless charms and delights due to some ineffable spirit that overshadows everything else. Ultima VII is the finest example of this type that I can think of. Its list of trouble spots is longer than that of many genuinely bad games, and yet its special qualities are so special that I can only recommend that you play it.

The special qualities of Transport Tycoon are special enough to yield the same recommendation. Most games focus on destruction in one way or another; the designer presents you with a complete, functioning system, and then you go through and tear it all down. How wonderful to be able instead to point at a smoothly humming thing of beauty on the screen and know that you built that.

So, the superlative reviews that followed Transport Tycoon‘s release were perhaps justified in spite of it all. “If you like the kind of ‘toying around’ and micromanagement offered by SimCity,” wrote Computer Gaming World magazine, “you might find that your romantic partners will split up with you, you will lose your job, your pets will starve, your computer will overheat, and you won’t even notice.” PC Gamer, the emerging populist rival to that older, more high-toned magazine, simply said that Transport Tycoon was “as good as PC gaming gets.” Edge magazine in Britain wrote that “it’s clear that Railroad Tycoon was a mere rehearsal. Transport Tycoon takes open-ended strategy games a giant step further.”

The game proved popular enough that MicroProse released a modestly enhanced Transport Tycoon Deluxe the following year, with optional fixed instead of randomly generated maps, with an editor for making your own versions of same, with new environments (arctic, tropical, or the ultra-whimsical Toy Land), and with some tweaks to gameplay (railroad signals grew somewhat more complex and flexible, and the timeline was shifted twenty years forward to run from 1950 to 2050, with a correspondingly more futuristic selection of vehicles on offer by the end). Rather bizarrely, however, no effort was made to fix the game’s fundamental issues of poor artificial intelligence, too much busywork, a broken economy, and an over-extended play time. In this sense, the deluxe edition was a colossal missed opportunity. Transport Tycoon is a really fun game even with all of its infelicities; without them, it could have been a staggeringly great one.

Indeed, Transport Tycoon‘s peculiar combination of fascination and frustration caused it to become one of those games that players felt a compulsion to somehow fix. Ten years worth of fan-made patches and tweaks finally yielded in 2004 to the first release of OpenTTD, an open-source clone of the game. The latter has continued to receive updates ever since, and has joined the likes of FreeCiv and NetHack as a staple of what we might call “hacker gaming.” As such, it evinces both the typical advantages and disadvantages of its species. A huge array of options and add-ons is available to correct every one of the problems I’ve outlined above and then some, but the process of choosing the right ones and putting them all together can be daunting, enough so as to drive away the player who just wants a fun, balanced game that plays well right out of the (virtual) box.

But enough of that; this is intended to be a review of the original Transport Tycoon rather than its later incarnations. In any such review, the obvious point of comparison remains its inspiration of Railroad Tycoon. This fact is not always to Transport Tycoon‘s benefit: it cannot be denied that the older game is also the more fully-realized. There are many reasons to prefer it: its carefully honed balance, the verisimilitude provided by its deeper connection to real history, its slightly more advanced train management (I dearly miss in Transport Tycoon the ability to change your trains’ consists automatically at stations), the fact that you can reasonably expect to finish a single game in an evening or two. And yet there’s something to be said as well for Transport Tycoon‘s more easygoing personality and more pronounced sandbox flavor, not to mention its groundbreaking interface and delightful aesthetic presentation. If I had to choose one, the critic and the pedant in me would demand that I take Railroad Tycoon. But luckily, we don’t really have to choose, do we?

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of October 1991 and March 1995; Edge of December 1993, February 1994, and February 1995; Electronic Entertainment of March 1995; Retro Gamer 4, 8, 58, 74, 98, and 138. Online sources include a Wired profile of Chris Sawyer and a EuroGamer interview with him, as well as his own home page.

Transport Tycoon has never received a digital re-release. I therefore take the liberty of hosting a version here that’s ready to run; just add the Windows, Macintosh, or Linux version of DOSBox. Do note, however, that most modern players prefer OpenTTD, which is free in all senses of the word.)