Book publishers, book authors, and booksellers first discovered computer software in 1983. Spurred by the commercial success of early text adventures like Zork and The Hobbit and by the rhetoric surrounding them, which described the new frontier of text-based digital interactive storytelling as the beginning of a whole new era in literature, publishers like Simon & Schuster, Addison-Wesley, and Random House made significant investments in the field, even as authors from Isaac Asimov to Roger Zelazny signed on for book-to-text-adventure conversions. Meanwhile B. Dalton and Waldenbooks, the two largest bookstore chains in the United States, set aside substantial areas in their stores for software. (Ditto W.H. Smith in Britain.) Those shelves were soon groaning with “computer novels,” “interactive novels,” and “living literature.” Well-known books in the genres of science fiction and fantasy, along with mysteries, thrillers, horror novellas, comic novels… all became computer games. Even the venerable likes of William Shakespeare, Hans Christian Andersen, and Robert Louis Stevenson appeared in shiny new interactive editions. A future American Poet Laureate wrote a text adventure, and Simon & Schuster came within a whisker of buying Infocom, the king of what the latter now preferred to call “interactive fiction” rather than mere text adventures.

This era of “bookware” was as short-lived as it was heady. In 1983, contracts were signed and groundwork was laid; in 1984, bookware products began reaching the public in large numbers; in 1985, with only Infocom’s adaptation of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy having lived up to its maker’s commercial expectations, book publishers began nervously formulating their exit strategies; in 1986, the last stragglers reached the market almost unremarked and bookware passed into history. With computer graphics and sound rapidly improving, game makers now set off to hunt the chimera of the interactive movie instead of the interactive book. It seemed that bookware had been nothing more than an exercise in faulty metaphors.

But then, exactly one decade after the beginning of the first bookware boom, it all started up again, as many of the same big names from last time around woke up to the potential of computer software all over again. Instead of parser-driven text adventures, however, they were now entranced by the notion of the CD-ROM-based electronic book: a work of non-fiction or fiction that was designed to be read non-linearly, for which purpose it was strewn with associative hyperlinks, and that incorporated photographs, illustrations, diagrams, sound effects, music, and video clips to augment the text wherever it seemed appropriate. In the face of all these affordances, some believed that the days of the paper-based book must surely be numbered. The big book publishers themselves weren’t so sure, but were terrified of being left behind by something they didn’t quite understand. “Everyone knows this business [of multimedia CD-ROMs] is potentially enormous,” said Alberto Vitale, Random House’s hard-driving CEO. “But what kind of shape it will take, how big it will actually be, and how it will evolve remains a very big question mark.” Laurence Kirshbaum of Warner Books was blunter: “I don’t know if there’s the smell of crisis in the air, but there should be. Publishers should be sleeping badly these days. They have to be prepared to compete with software giants like Bill Gates.”

The book publishers coped with the uncertainty in the way that big companies often do: by throwing their weight and money around in an attempt to bludgeon their way into continued relevance. And none of them did so more energetically than Alberto Vitale’s Random House. In 1993, they signed a high-profile deal with Broderbund Software to produce multimedia versions of Dr. Seuss’s classic children’s books, sending the smaller company’s share price soaring from $3.75 to $41 and sending a sum of money “well into the seven figures” to the late author’s widow. They also invested in Humongous Entertainment, a publisher of children’s edutainment founded by the Lucasfilm Games veteran Ron Gilbert, to create a series of “Junior Encyclopedias.” They formed their own software-distribution arm, under the tech-trendy portmanteau appellation of RandomSoft, to move the products of their partners and friends into bookstores. And, in the summer of 1994, in a deal that represented the most obvious throwback yet to the previous era of bookware, they invested $2.5 million in Legend Entertainment.

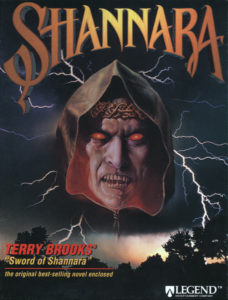

The investment didn’t come out of the blue: the two companies had worked together before. In 1991, Legend had sought and acquired a license to make a pair of games based on Random House author Frederick Pohl’s Gateway series of science-fiction novels. That deal had been followed by two more, to make games based on Piers Anthony’s Xanth series and Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s Death Gate series. Legend, in other words, had been making bookware games for Random House on their own initiative since before the latter even knew they wanted such things. Now that that realization had dawned, Random House’s investment would serve to bind Legend closer to them and ensure that more of their books could become well-executed games. They already had a first candidate in mind: the bestselling Shannara series of high-fantasy novels.

The Sword of Shannara, the first book in the series, had appeared in 1977, one of the early heralds of a post-Dungeons & Dragons boom in fantasy fiction that would soon cause the fantasy genre to utterly eclipse its traditional sibling genre of science fiction in sales. The author of the 700-plus-page epic was Terry Brooks, a 33-year-old attorney who had spent the last ten years working on it intermittently in his spare time. The very first novel to be published by the new science-fiction and fantasy imprint Del Rey Books, it was a huge success right from the start; it sold 125,000 copies in its first month and became the first fantasy novel to make the New York Times bestseller list for trade paperbacks. But at the same time, it was savaged by even much of the genre-fiction establishment as little more than bad Lord of the Rings fan fiction. The prominent editor and critic Lin Carter, for example, pronounced it “the single most cold-blooded, complete ripoff of another book that I have [ever] read.” From a further remove in time, the J.R.R. Tolkien expert John Lennard can describe it only slightly more kindly today as “the first of a number of overt imitations of The Lord of the Rings that are, however popular, manifestly inferior works, but testify to the taste for [the] high and extended fantasy epic that Tolkien created.”

As Lennard’s recent dismissal of Shannara suggests, the combination of big sales and deep-seated critical antipathy has clung to the series right to the present day, as has Terry Brooks’s status as Public Offender #1 in the rogue’s gallery of Tolkien ripoff artists. Shannara is, the scoffers say, a simulacrum of the surface elements of The Lord of the Rings — warriors and wizards, magical swords and apocalyptic battles — without any of its thematic depth or philosophical resonance, a charge which even Brooks’s fans must find difficult to entirely refute. On the other hand, the same description applies to thousands of other works of fantasy in book, movie, and game form, so why single this one out so particularly? Brooks himself was and is by all indications a decent sort, who loves his work and has few illusions about his place in the literary pantheon. “I don’t have any desire to write the great American novel,” he said in 1986. “Why experiment with something that’s an unknown quantity when I’m comfortable working with fantasy?” He noted forthrightly in 1995 that he wasn’t exactly catering to the most refined literary tastes: “I think you are most intense in your reading habits when you’re in your teenage years. Magic is ‘real,’ your hormones are raging, and you’re more open. When I’m writing, I’m always writing to that group of people.” For all that I may have no personal use for the likes of a Terry Brooks novel at this stage of my life, I and every other critic should keep in mind the wise words of Edmund Wilson before rushing to condemn his books too lustily: “If other persons say they respond, and derive from doing so pleasure or profit, we must take them at their word.”

Brooks himself was not a gamer in 1994, but his twelve-year-old son was: “I enjoy watching him,” he said at the time. He hit it off wonderfully with Bob Bates of Legend at their first meeting, and was excited enough to describe this partnership as the potential beginning of a whole new, trans-media era for the Shannara series: “I like the idea that I will continue to write the books and others will work on projects which surround the timeline, characters, and settings I’ve established.”

It sounded like an excellent plan to everyone involved. But alas, Shannara‘s computer debut would turn into a “troubled” project, the first of that infamous breed of game in Legend’s relatively drama-free history up to that point. It was plagued by communications problems and a mismatched set of expectations on the part of Legend and Corey and Lori Ann Cole, the game’s out-of-house design team. But, having talked at length to both Bob Bates and Corey Cole about what went down, I can confidently say that no one involved is angry or vindictive about any of it today; “sad” would be a more accurate adjective. Everyone involved was genuinely trying to make his or her own vision of Shannara into the best game it could possibly be. And, as we’ll see in due course, the end result actually succeeds pretty darn well in spite of itself.

The Coles first came to work with Legend due to a pressing lack of in-house designers capable of taking on the Shannara project. At the time the Random House deal was consummated, Bob Bates was working on an “ethics training game” for the American Department of Justice, an odd but profitable sideline from Legend’s main business of making adventure games, while Steve Meretzky had recently moved on to start his own software studio. Of the three trainee designers who had made Gateway a few years before — a project consciously conceived as a sort of designer boot camp — Glen Dahlgren was finishing up Death Gate, Mike Verdu was in the planning stages of a non-licensed game called Mission Critical, and Michael Lindner was planning a sequel to the non-Legend game Star Control II. Programmers were in similarly short supply. Legend was a company with more food on its plate than it could eat, which was definitely better than the opposite situation, but a problem nonetheless. They wanted very much to please Terry Brooks and Random House by making a great Shannara game in a timely fashion, but they just didn’t have the bodies to hand to do so. So, they decided to look for outside help.

Bob Bates had met the Coles for the first time before Legend even existed, at a dinner hosted by Computer Gaming World editor Johnny L. Wilson during the late 1980s. He liked them personally, and was pleased for them when the Quest for Glory series which they were creating for Sierra did well. He started to talk seriously with them about doing a game for Legend in early 1994, when their future with Sierra was looking more and more uncertain in light of that company’s push into bigger-budget interactive movies starring real actors. Within weeks of that conversation, the worst happened: Quest for Glory V was cancelled in its early design phase and the Coles were told that their services were no longer required by Sierra.

Thus when Random House strongly suggested that Legend make a Shannara game, it seemed like kismet to everyone concerned. Not only were the Coles highly respected adventure-game designers, but specialists in the fantasy breed of same. Still, the source material initially “gave us pause,” admits Corey.

Both Lori and I had read The Sword of Shannara in college, and we weren’t impressed. We considered it a blatant Lord of the Rings copy. Sad to say, we enjoyed both Raymond E. Feist and David Eddings more than Terry Brooks.

However, we decided to keep our minds open and reread The Sword of Shannara. My revised opinion was that the first one-third of the book was a blatant ripoff, but after that, the book delved into new territory and became its own work. We went on to read The Elfstones of Shannara [the second book in the series] and agreed that it had merit. Our belief is that Brooks started out as a beginning writer thinking the way to make a book as successful as The Lord of the Rings was to essentially write the same book. But as he went along, he developed his own authorial voice and became a much stronger writer.

Terry Brooks gave the Coles his all-important nod of approval after they met with him and showed themselves to be familiar with his work. “There’s the matter of losing control,” he conceded, “but when I talked to these folks and realized how much they cared about the books and the characters, I felt better.” The Coles proposed slotting an original story between the first and second books in the series — for here there was, as Bob Bates puts it, “a generational gap”: “the hero of the second book was the grandson of the hero of the first book.”

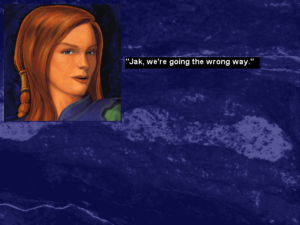

The hero of the Coles’ game, then, would be the son of the hero of the first book. The game would take place about ten years after said book’s conclusion, casting the player in the role of Jak Ohmsford, son of Shea. (The Ohmsfords and their fellow residents of the bucolic Shady Vale are the equivalent of Tolkien’s hobbits of the Shire). Jak would learn from the wizard Allanon (Gandalf) that Brona (Sauron) was feeling his oats once again and was up to no good. The quest that followed would take Jak and the party of companions he would acquire across the length and breadth of Brooks’s well-developed if less than breathtakingly original fantasy world, at minimal cost to the continuity of the extant novels.

The Coles were friendly with a fellow named Bob Heitman, who had worked for years at Sierra as one of the company’s best software engineers, until he had left with Sierra’s chief financial officer Edmond Heinbockel and Police Quest designer Jim Walls to form Tsunami Media, a somewhat underwhelming attempt to do what Sierra was already doing. (Tsunami was also another player in the second bookware boom, creating a pair of poorly received games based on Larry Niven’s Ringworld series.) Now, Heitman had cut ties with Tsunami as well and set up his own software house, which he called Triton Interactive. Between them, the Coles and Triton should be able to make the Shannara game using Legend’s technology, with only light supervision from Bob Bates and company — which was good, considering that Legend was located in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Chantilly, Virginia, the Coles and Triton three time zones away in rural Oakhurst, California. The project began in earnest in the fall of 1994. All parties agreed that the Shannara computer game would be finished within one year — i.e., in time for the Christmas of 1995 — for a budget of $362,000.

The problems began to crop up on several separate fronts soon after the new year of 1995. Heitman could be abrasive; Corey liked to say that “some people do not suffer fools gladly, but Bob Heitman doesn’t suffer them at all.” Bob Bates, whom Heitman may or may not have considered a fool, was unimpressed with his counterpart’s shoot-from-the-hip way of running his development studio. Following a visit to Oakhurst in February, his assessment of Triton’s performance was not good:

1) No one is really taking charge of project management.

2) The animation requirement is up to 60 man-weeks, and they haven’t been able to hire any artists yet.

3) One background artist we supplied simply isn’t producing.

4) They’re not segmenting text from code, so there’s a big localization problem coming.

5) Internal personality problems are plaguing the team.

Bob Bates was also worried that Triton might use the software technology Legend was sharing with them in other companies’ projects, and almost equally worried that other companies’ code might sneak into Shannara with potential legal repercussions, given the chaos that reigned in their offices.

With tempers flaring, the Coles stepped in to try to calm the waters. They formed their own company, which they called FAR Productions, after Flying Aardvark Ranch, their nickname for their house in Oakhurst. Officially, FAR took over responsibility for the project, but the arrangement was something of a polite fiction in reality: FAR leased office space from Triton and continued to work with largely the same team of people. Nevertheless, the arrangement did serve to paper over the worst of the conflicts.

Meanwhile Bob Bates had other issues with the Coles themselves — issues which had less to do with questions of competence or even personality and more to do with design philosophy. The Coles had enjoyed near-complete freedom to make the Quest for Glory games exactly as they wanted them, and were unused to working from someone else’s brief. They wanted to make their Shannara game an heir to their previous series in the sense of including a smattering of CRPG elements, including a combat engine. Bob Bates, a self-described “adventure-game purist,” saw little need for them, but, perhaps unwisely, never put his foot down to absolutely reject their inclusion. Instead they remained provisionally included — included “for now,” as Bob wrote in February — as the weeks continued to roll by. In July, with the ship date just a few months away, combat was still incomplete and thus untested on even the most superficial level. “This would have been a good time to drop it,” admits Bob, “but we did not.”

While the one source of tension arose from a feature that the Coles dearly wanted and Bob Bates found fairly pointless, the other was to some extent the opposite story. From the very beginning, Bob had wanted the game to include an “emotion-laden scene” near the climax that would force the player to make a truly difficult ethical decision, of the sort with no clear-cut right or wrong answer. The Coles had agreed, but without a great deal of enthusiasm on the part of Lori, the primary writer of the pair. Considering Bob’s cherished ethical dilemma little more than a dubious attempt to be “edgy,” she proved slow to follow through. This caused Bob to nag the Coles incessantly about the subject, until Lori finally wrote a scene in which the player must decide the fate of Shella, the daughter of another character from the first novel and a companion in Jak’s adventures. (We’ll return to the details and impact of that scene shortly.)

But the ironic source of the biggest single schedule killer was, as Corey Cole puts it, having too few constraints rather than too many: “A mentor once told me that the hardest thing [to do] is to come up with an idea, or build something, with no constraints.” Asked by Bob Bates what they might be able to do to make the game even better if they had an extra $50,000 to hand, the Coles, after scratching their heads for a bit, suggested adding some pre-rendered 3D cut scenes. “If I had known then what I found out by the end of the project,” says Corey, “I’d have said, ‘No, thanks, we’ll finish what we started.’ I ended up sleeping at the office, since each render required hand-tweaking and took about four hours.”

Still more problems arose as the months went by. The father of the art director had a heart attack, and his son was forced to cut his working hours in order to care for him. Another artist — the same one who “simply isn’t producing” in the memo extract above — finally confessed to having terminal cancer; he wished to continue working, and no one involved was heartless enough not to honor that request, but his productivity was inevitably affected.

Legend had agreed to handle quality control themselves from the East Coast. But in these days before broadband Internet, testing a game of 500 MB or more from such a distance wasn’t easy. Bob Bates:

All development work had to cease while a CD was being burnt. Then it was Fed-Exed across the country, and then we would boot it. Sometimes it just didn’t work, or if it did work, there would be a fatal bug early in the program. The turnaround cycle on testing was greatly reducing our efficiency. By the time testers reported bugs, the developers believed they had already fixed them. Sometimes this was true, sometimes it wasn’t.

On October 2, 1995, about five weeks before the game absolutely, positively needed to be finished if it was to reach store shelves in time for Christmas, Bob Bates delivered another damning verdict after his latest trip to Oakhurst:

* There is no doc for the rest of the handling in the game. [This cryptic shorthand refers to “object-on-object handling,” a constant bone of contention. Bob perpetually felt like the game wasn’t interactive enough, and didn’t do enough to acknowledge the player’s actions when she tried reasonable but incorrect or unnecessary things. Lori Ann Cole, says Corey, “felt that would distract players from the meaningful interactions; she refused to do that work as a waste of her time, and potentially harmful to her vision of the game.”]

* The final game section is not coded.

* Combat is not done.

* Lots of screen flashes and pops.

* Adventurer’s Journal is not done.

* Too many long sequences of non-interaction.

* Too many places where author’s intent is not clear.

* Map events (major transitions) are not done.

* Combat art is blurred.

* Final music hasn’t arrived from composer.

As Bob saw it, there was only one alternative. He flew Corey Cole and one other Oakhurst-based programmer to Virginia and started them on a “death march” alongside whatever Legend personnel he could spare. Legend was struggling to finish up Mission Critical at the same time, meaning they were suddenly crunching two games simultaneously. “The fall of 1995 was really enjoyable at Legend,” Bob says wryly. “We coded like hell until the thirteenth of November. We hand-flew the master to the duplicators and the game came out Thanksgiving week. Irreparable damage [was done] to the team. We have not worked together since.” The final cost of the game wound up being $528,000.

The scale of Legend’s great Problem Project is commensurable with the company’s size and industry footprint. The development history of Shannara isn’t an epic that stretches on for years and years, like LucasArts’s The Dig; still less is it a tale of over-the-top excess, like Ion Storm’s Daikatana. Shannara didn’t even ship notably late by typical industry standards. Still, everything is relative: as a small company struggling to survive in an industry dominated more and more by a handful of big entities, Legend simply couldn’t afford to let a project drag on for years and years. In their position, every delay represented an existential threat, and outright cancellation of a project into which they’d invested significant money was unthinkable. For those inside Legend, the drama surrounding Shannara was all too real.

But the Shannara story does have an uncommon ending for tales of this stripe: the game that resulted is… not so bad at all, actually. It’s not without its flaws, but it mostly overcomes them to leave a good taste in the mouth when all is said and done. In the interest of being a thorough critic, however, let me be sure to address said flaws, which are exactly the ones you would expect to find after reading about the game’s development.

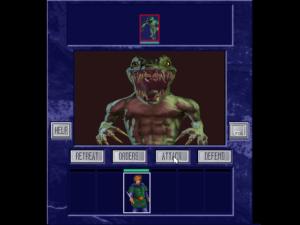

One might say that Shannara is at its worst when it’s trying to be a Quest for Glory. Lacking the time and resources to make the game into a full-fledged CRPG/adventure hybrid, but determined not to abandon what had become their design trademark, the Coles settled for a half-baked combat engine that’s unmoored from the rest of the game and ultimately, as Bob Bates noted above, rather pointless. With no system of experience points or levels being implemented, you earn nothing from fighting monsters, even as the whole exercise further fails to justify its existence by being any fun in its own right. There are the seeds of some interesting player choices in the combat engine, but they needed much more work to result in something compelling. Legend’s last-minute solution to the problem during that hellish final crunch was to dial the difficulty way, way back, thereby trivializing the combat without eliminating it. Such compromises serve no one well in the end.

In the name of fairness, I should note that Corey Cole offers a different argument for the combat being there at all and taking the form it does — one that I don’t find hugely convincing on the face of it, but to each his own:

The “pointless combat” is very much as planned in the design. It’s an anti-war point that fits closely into the Sword of Shannara zeitgeist, and which we reinforced in the game text: there are no winners in war (or in battle). The enemy forces are vast, and our hopefully realistic characters are not superheroes. Their object is to traverse the map while fighting as little as possible. When they do fight, it is risky and saps the party’s strength. Think of the hobbits vs. the ringwraiths atop Amon Sul (Weathertop). They had no chance. That’s Jak and Shella’s situation against the forces of Brona. The “win condition” is escaping with their lives.

I must confess that I struggle to identify much of an “anti-war point” in a series of books which revels in an endless series of apocalyptic wars, but I’ve only skimmed the surface of Terry Brook’s huge oeuvre. Perhaps I’m missing something.

Bob Bates’s own hobby horse — his big ethical dilemma — doesn’t fare much better in my opinion. Near the end of the game, Jak’s companion Shella is mortally wounded by an evil shifter. (Shifters are Brooks’s version of Tolkien’s ringwraiths). If allowed to expire on her own, her soul will be claimed by Brona. Another of Jak’s companions can heal her using the magical Elfstones he carries, but expending them now will mean he can’t use them for their intended purpose of stopping Brona’s plans for world domination in their tracks. Jak’s only other choice is to kill Shella himself, then perform a Ritual of Release to free her soul; this is what she herself is begging him to do. It certainly sounds like a difficult choice in the abstract. Once again, though, a difference in design priorities resulted in a half-baked compromise in practice. In the finished game, saving Shella with the Elfstones results in a few screens of text followed by a game over — meaning that the ethical choice isn’t really a choice at all for any player who wishes to actually finish the game she paid good money for. The whole comes across as overwrought rather than moving, manipulative rather than earnest.

Yet neither the halfhearted combat nor the half-baked moral choice fills enough of the game to ruin it. Constrained though the Coles may have been from indulging in another of the delightful free-form rambles that their Quest for Glory series was at its best, they remained witty writers well able to deliver an entertaining guided tour through Terry Brooks’s world. And despite all the day-to-day problems on the art front, the final look of the game lives up to Legend’s usual high standards, as does the voice acting and the music by the legendary game composer George “The Fat Man” Sanger. If the puzzles are seldom anything but trivially easy — a conscious design choice for a game that everyone hoped would, as Corey Cole puts it, “attract many Terry Brooks fans who had no previous adventure-game experience” — they give the game a unique and not unwelcome personality: Shannara plays almost like an interactive picture book or visual novel rather than a traditional hardcore adventure game. With so little to impede your progress, you move through the story quickly, but there’s still enough content here to fill several enjoyable evenings.

Upon its release, Shannara approached 100,000 units in sales, enough to turn a solid profit. Although its impact on the market was ultimately less than what Random House and Terry Brooks had perhaps hoped for, its relative success came as a relief by this point to Bob Bates and everyone else at Legend, who had had such cause to question whether the game would ever be finished at all. Reviews, on the other hand, tended to be unkind; hardcore gamers looking for a challenge were all too vocally unimpressed with the game’s simple storybook approach. Computer Gaming World‘s adventure columnist Scorpia went on a rather bizarre rant about the fate of Shella, which she somehow twisted into a misogynistic statement:

I would not have minded had she died gloriously in battle; that is often the fate of heroes and heroines. What happens is: Shella is mortally wounded, but lingering on, and Jak — to save her soul — must kill her on the spot and perform a certain ritual. The only woman in the entire game, and she not only dies, but goes out a helpless lump.

I’ve heard that game designers are wondering how they can get more women playing games; if they keep presenting us with garbage like this, it isn’t going to happen anytime soon. Far too many products these days have exclusively male heroes doing this, that, and the other; women are either nonexistent or mere adjuncts, at best.

While I agree wholeheartedly with Scorpia’s last sentence in the context of the times, the rest of her outrage seems misplaced, to say the least. Shella is never presented as anything other than strong, smart, and brave in Shannara, and she dies nobly in the end. Any number of other games would have made a more worthy target for Scorpia’s ire.

For my own part, I can happily recommend Shannara to anyone looking for a bit of comfortable, non-taxing fantasy fun. “In hindsight, we’re very proud of the game we made,” says Corey Cole. That pride is justified.

The inclusion of Terry Brooks’s novel in the Shannara box is a throwback to the olden days of bookware.

There’s a seemingly free-form overland-movement view, although the places to which you can actually travel are always constrained by the needs of a linear plot. Monsters wander the map as well. You can attempt to fight or avoid them; most players will find the latter preferable, given how unsatisfying combat is.

The combat screen. There are the seeds of some interesting ideas here — the Coles could always be counted on to put some effort into their combat engines — but it’s poorly developed.

Shella and Jak keep up a nice, flirting banter throughout most of the game. Like so much here, their relationship has the flavor of a well-done young-adult novel. Belying the bad feelings that came to surround its making at times, Shannara never fails to be likable from the player’s perspective, a tribute to Corey Cole’s professionalism and to Lori Ann Cole’s deft writerly touch.

(Sources: the books Tolkien’s Triumph: The Strange History of The Lord of the Rings by John Lennard, Axel’s Castle: A Study of the Imaginative Literature of 1870-1930 by Edmund Wilson, and the post-1991 edition of Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks; Computer Gaming World of November 1994, November 1995, and March 1996; Starlog of June 1986; CD-ROM Today of June/July 1994 and January 1995; New York Times of September 11 1993 and May 22 1995; Newsweek of August 13 1995; Los Angeles Times of April 21 1994; Atlantic of September 1994. Most of this article, however, is drawn from an interview with Bob Bates and internal Legend documents shown to me by him, as well as an email correspondence with Corey Cole. My huge thanks go out to both of them for taking the time.

Shannara is not available for purchase today, but you might find the CD image archived somewhere — hint, hint — if you look around. I’ve prepared a stub of the game that’s ready to go if you just add it to the appropriate version of DOSBox for your platform of choice and a BIN/CUE or ISO image of the CD-ROM.)