The Heroes of Might and Magic series of fantasy strategy games was an anomaly during its period of peak popularity at the turn of the millennium: it remained defiantly turn-based in an industry that had gone almost entirely real-time, and it likewise continued to rely on lovingly hand-drawn pixel art in lieu of trendy 3D graphics. All of this gave the series the feel of — dare I say it? — a board game, at a time when such things were deeply out of fashion with digital gamers looking for the latest and greatest in immersive whiz-bang pyrotechnics. And yet it sold millions upon millions of copies.

When we dig a bit deeper, we find that the origins of Heroes‘s retro tabletop sensibility are as explicable as its popularity is inexplicable. As we learned in the last article, its principal creator Jon Van Caneghem was a tabletop gamer long before he became a computer gamer, much less a computer-game designer and programmer. Heroes of Might and Magic was as heavily influenced by the delightfully tactile boards, cards, counters, and dice which had marked his adolescence as it was by anything he had seen or done on a computer since. More specifically, it was the belated fruit of what had once seemed a quixotic attempt on his part to bridge the analog-versus-digital split in gaming — a venture which dated back to more than seven years before the first game in the Heroes series arrived in late 1995.

One of the young Jon Van Caneghem’s favorite tabletop games was Star Fleet Battles, a “simulation” of outer-space combat in the Star Trek universe. His love for it persisted even after he decided to become a computer-game entrepreneur. Indeed, the self-described Star Fleet Battles “fanatic” found time amidst the run up to the release of the original Might and Magic to win the game’s biggest tournament in 1986, thus securing for himself the status of best player in the world as of that instant in time.

The publisher of Star Fleet Battles was an Amarillo, Texas-based outfit known as Task Force Games. Two plucky freshly minted Texas Tech graduates named Stephen Cole and Allen Eldridge had founded Task Force in 1978, whereupon they had managed to acquire a license for one of the biggest science-fiction properties in the world by employing a circuitous — not to say dubious — stratagem: they had sub-licensed the intellectual property from Franz Joseph, the author of a tome called the Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual. Task Force would eventually secure a more direct contract with Paramount Pictures, the owners of Star Trek, but their game would always live on precarious legal ground, entirely at the sufferance of a corporate overlord which seemed only intermittently to realize that it existed. The tortuously circumscribed contract which allowed Task Force to make their game stipulated that they could use the ships and hardware and the various alien societies and races from the television show, but that they couldn’t mention specific characters or plot lines. Nevertheless, Star Fleet Battles has survived if not always thrived right up to the present day, even as countless other, higher profile efforts to make interactive versions of Star Trek have come and gone.

In 1983, Cole and Eldridge parted ways to some extent: the former started a new company called Amarillo Design Group to conjure up fresh Star Fleet Battles rules, scenarios, and supplements, while the latter continued as the head of Task Force, which in turn remained the publisher of the aforementioned game line and others. Some five years later, word reached Jon Van Caneghem at New World Computing, now flush with the commercial success which Might and Magic was enjoying, that Eldridge was interested in selling Task Force. It struck Van Caneghem as a chance to become a new type of gaming mogul, uniting the worlds of tabletop and computer gaming under a shared umbrella for the very first time. The dedicated grognards at Task Force could become a “proving ground for systems” on the tabletop before they were implemented on the computer, and product lines too could cross and recross the digital divide in pursuit of synergies no one had yet dared to imagine.

So, New World purchased Task Force and moved them into their offices in Van Nuys, California. Stephen Cole insisted on retaining control of the Amarillo Design Group and keeping it in its namesake city, but he did agree to continue to provide Task Force with their most prominent product line. To run the tabletop side of his empire, Van Caneghem hired one John Olsen, a board-gaming insider with an impressive resume; he had most recently headed the major British tabletop publisher Games Workshop’s American operation.

The whole scheme appealed greatly to a dedicated old-school gamer like Van Caneghem, but it was in reality muddle-headed in the extreme. He had bought into the tabletop industry when it was smack in the middle of a brutal downturn, prompted largely by, ironically enough, computer games. Avalon Hill, the old king of hobbyist wargames, was bleeding money, and even the likes of Dungeons & Dragons was rather less than it once had been. It would be some years yet before collectible card games and a new breed of ruthlessly balanced abstract board games known as “Eurogames” would breathe life back into the tabletop market. In the meantime, it was a disheartening place to be, where the only people making any real money were the big conglomerates marketing hoary family staples like Monopoly. “We really made a go at board games, but compared to the dollars and profitability of software… there was just no comparison,” Van Caneghem would later admit. “It didn’t make any sense.”

But that realization would take some time to fully dawn on him. Thus the output of New World Computing immediately after 1988’s Might and Magic II was dominated by the tabletop-to-computer (or vice versa) synergies Van Caneghem hoped to create. Granted, Task Force’s biggest property of all was a nonstarter here: there was no way that Paramount was going to allow Star Fleet Battles onto computers to compete with other efforts to bring Star Trek to the digital realm. But Task Force also had a long-established relationship with the Arizona game maker Flying Buffalo, and now served as a conduit for bringing some of the latter’s designs to the computer. First came a credible port of the venerable satirical card game Nuclear War. And then came a more ambitious project, a computer game based on Tunnels & Trolls, Flying Buffalo’s simpler would-be rival to Dungeons & Dragons. The system being very popular in Japan, this project became a trans-Pacific collaboration: a design document was written by the Flying Buffalo regulars Elizabeth Danforth and Michael Stackpole (both of whom already had a track record with computer games as well), then passed to a team in Japan for implementation. Finally, said team sent it sent back to New World to be made presentable in its original language. Unsurprisingly, the finished product felt more than a trifle schizophrenic, while its audiovisuals captured the charmingly pulpy, low-rent feel of its tabletop source material perhaps a bit too well for the presentation-driven contemporary computer-game market. “It didn’t go over all that well” in its native country, admits Van Caneghem, although it did do somewhat better in Japan.

But the most interesting of all the products of this rather confused period in New World Computing’s history is also the one which came closest to being a truly synergistic effort. Rather than being a tabletop game ported to the computer, King’s Bounty had one foot planted squarely in each realm from first to last.

It all started when Jon Van Caneghem began musing one day about how to bring some of the flavor of another of his old tabletop favorites to the computer: a board game known as Titan, one of those gloriously messy experiences from the heyday of Avalon Hill, the sort of game in which half the players might be eliminated in the first hour while the other half grind away at one another for five or six hours more. In Titan, players move their “stacks” of monsters over a highly abstracted map, trying to recruit additional monsters to add to their legions even as they also try to outmaneuver and attack the other players’ stacks when the advantage is with their side. When two players’ armies do bump into one another, the focus shifts to a tactical battle map representing the terrain in which the clash is occurring. The ultimate goal is to defeat each of your opponents’ titans — their super-units, the equivalent of the king in chess — as this is the only way to force them out of the game; you must also be careful to protect your own titan, of course. Getting to the end of a game of Titan can be a long journey indeed, one that can be by turns riotously entertaining and numbingly tedious.

Fond though he was of the game, Van Caneghem felt it would be problematic to bring a similar experience to life on the computer, mostly because of the difficulty of implementing an opponent artificial intelligence able to challenge a human player; at the time, New World was still making their games for 8-bit platforms with as little as 64 K of memory, which didn’t leave much scope for such things. But then Van Caneghem happened to talk to John Olsen about a concept Task Force had in development, with the working title of Bounty Hunter. Designed primarily by one Robert L. Sassone, it cast its players as the titular vigilantes for hire, moving around a board trying to nab more fugitives than their opponents. Van Caneghem thought the idea was brilliant in a big-picture sort of way, but a trifle under-baked in the details. But what if they combined it with some of the themes and mechanics of Titan? And what if they then made it into both a computer game and a board game?

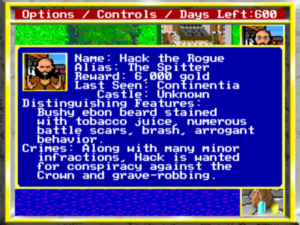

The resulting game of King’s Bounty first appeared on computers in 1990, beginning with versions for the Apple II and for MS-DOS machines. Living in the hazily delineated borderlands between the CRPG and strategy genres, it was a refreshingly light-hearted, fast-playing change of pace from the more ponderous epics which dominated to either side of it. You start out by picking one of four protagonists to guide: the Knight, the Paladin, the Barbarian, or the Sorceress. Then you proceed to wander the four continents of its world, fighting some monsters and recruiting others, visiting towns, besieging castles, looting treasure chests, and, yes, capturing villains for bounties, growing steadily stronger all the while. In addition to a cash reward, each successfully hunted bounty reveals another piece of a treasure map, an idea cheerfully stolen from Sid Meier’s Pirates!. Said map points the way to the King’s Sceptre, the recovery of which ends the game in victory. Rather than competing directly against a computer opponent who tries to accomplish the same goal as you, you battle the calendar: you have between 200 and 1000 days to complete your quest for the Sceptre, depending on the difficulty level you choose. By this means was New World able to dodge the problem of creating an artificial intelligence capable of going head to head with a human player.

A complete game of King’s Bounty generally takes only a few hours, making it a positively snack-sized offering in comparison to the 100-hour-plus likes of a Might and Magic. Yet it provides a compressed version of the same satisfying power fantasy — what Alan Emrich, reviewing King’s Bounty for Computer Gaming World magazine, called “expanding megalomania.”

There is some sort of intangible “charge” that comes out of seeing one’s character become a more powerful warlord, leading bigger armies, gaining an ever-increasing commission, subduing ever larger foes, and so forth. While this is hardly an original concept (it dates back to the first games of Dungeons & Dragons), it still holds an endearing appeal when done well. In King’s Bounty, this “Monty Haul” brand of adventuring is exquisitely executed, rewarding the player with plenty of strokes on his way to finding the Sceptre.

Unlike the typical one-and-done CRPG, the computer game of King’s Bounty is designed to be played multiple times, as one would a board game. Not only are there four protagonists and four difficulty levels to choose from, but the placement of monsters, treasures, bounties, and the Sceptre itself is randomized with each new game. If it isn’t a hugely deep game even by the standards of its day, it can be an entertaining one for far more hours than a rundown of its simple mechanics might suggest. As we’ll soon see, this trait along with many of its other, more prosaic qualities would return years later in the more famous series of games for which it served as something of a prototype.

In the here and now of 1990, however, King’s Bounty on the computer proved a modest commercial success but not a sterling one. By the time it appeared, Jon Van Caneghem had reluctantly acknowledged that it was tough enough for his company to survive as a maker of computer games alone, and was in the process of divesting New World of Task Force Games: he sold out to John Olsen, who then moved Task Force back to Amarillo. In 1991, Olsen’s Task Force finally published the board game of King’s Bounty. It preserved most of the key elements of the computer game in forms modified to suit the tabletop, but it attracted little attention in a moribund marketplace, and quickly went out of print. (Task Force itself would continue to release new products until 1996 and to market the best of the old ones until 2004.)

Meanwhile, with the dream of making analog and digital games side by side now consigned to the past alongside other follies of youth, Van Caneghem retrenched and refocused on New World Computing’s core commercial strength: namely, the Might and Magic CRPG series. New World made a slick new engine that left behind 8-bit machines like the Apple II, then made three new Might and Magic games with it between 1991 and 1993. During this period, as these games were garnering strong reviews and equally strong sales, it was easy enough to see King’s Bounty as just one more misbegotten sign of a confused time.

But by 1994, the Might and Magic line seemed to be losing momentum, in tandem with a dramatic downturn in the CRPG market in general. The new standard bearers for narrative-oriented games were tightly scripted “interactive movies” like Under a Killing Moon, along with 3D-rendered slideshow adventures like Myst; many had come to see the sort of sprawling, open-ended high-fantasy CRPGs which New World made as relics of the past. New World stood at a proverbial fork in the road. Their second-generation Might and Magic engine too had now passed its sell-by date. Did they damn the torpedoes and surge ahead with the expensive task of making a new one for a genre that had fallen so badly out of fashion? Or did they try something else entirely? Van Caneghem looked around and weighed his options.

The enormous success of id Software’s Wolfenstein 3D and DOOM had heralded the emergence of a less highfalutin and more visceral, action-oriented strand of computer gaming to challenge the artsier experiments of the period. Yet computer gaming as a whole has never been a monolithic or even a bifurcated beast. Along with the likes of DOOM and Myst, that yang and yin of the era, strategy games were enjoying a quieter golden age in the wake of such classics as Railroad Tycoon, Civilization, and Master of Orion. Further, some of the latest explorations of the genre almost seemed to have taken a lesson from King’s Bounty about the appeal of CRPG-style character building within a strategic framework: X-COM and Master of Magic remain famous to this day for the intense personal bonds they forge between their characters and the players who control them. Perhaps, mused Van Caneghem, King’s Bounty had just been a bit too far ahead of the curve, implemented using technology that couldn’t quite do justice to its concept. Perhaps he should try again.

But, this being an older and wiser Jon Van Caneghem, he would do some things differently this time. Whatever the current state of the CRPG market, the Might and Magic name still had the benefit of widespread familiarity. Why let that go to waste? Why not make the new game a spinoff of Might and Magic rather than a completely new, completely unfamiliar thing?

And so Heroes of Might and Magic was born. Van Caneghem could hardly have imagined how successful it would prove on every level, from the crass commercial measure of units sold to the more idealistic one of hours of fun delivered to millions of people all over the world.

At this point, I owe it to those readers who aren’t among said millions to explain just what Heroes of Might and Magic is all about. It has ironically less to do with the CRPG series whose name it borrows than it does with King’s Bounty. Beyond sharing a fantasy theme that involves plenty of monster killing and leveling up as a reward for it, and some halfhearted efforts to tie it into the CRPG series’s universe, it has almost nothing to do with its older namesake. “If not for copyright lawyers, Heroes of Might and Magic could as easily have been called Heroes of Ultima, Heroes of Wizardry, or Heroes of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons,” noted Jason Kapalka accurately in his review of the first game in the series for Computer Gaming World.

But even the influence of King’s Bounty shouldn’t be overstated. For all that its roots so plainly lie there, Heroes is at bottom a very different sort of game; there’s far more distance between King’s Bounty and the first Heroes than there is between the latter and any of the subsequent entries in the series. Heroes abandons the business about bounty hunting in favor of being a true strategic wargame, complete with computer and/or human opponents who are trying to conquer the same map that you are. Rather than guiding a single hero, you can now recruit and control up to eight of them, along with the sedentary garrisons you collect to defend your castles against the other players whose heroes are also roaming the map with their armies.

Newbies to the series today are often advised to skip the first game, on the argument that everything it does is done bigger and better by the later ones. This is true enough as a statement of fact; those games are packed full of much more stuff — stuff which, in contrast to that found in many sequels, really does make an already compelling game that much more compelling. Still, I don’t really agree with the argument that this fact makes Heroes I extraneous. On the contrary, it strikes me as a perfect place to start with the series. It introduces the core concepts that carry through all of the subsequent games, leaving those successors free to layer their additional complexities and nuances onto its sturdy frame. So, this article will focus exclusively on the often neglected first game. There will be plenty of time to praise the others in later articles.

At the time of its release in the fall of 1995, Heroes I seemed merely the latest exemplar of what was already a long tradition of fantasy strategy on the computer. The most notable recent game of this sort had been Steve Barcia’s Master of Magic. It and Heroes of Might and Magic share many similarities: both are games of conquest that expect you to recruit and nurture individual heroes to lead your armies, even as you also guide the development of the castles and towns that spawn the soldiers who fight under them; both prominently feature the magic that is found in both their names; both shift between a strategic map where the big decisions are made and a tactical view used for battles. Yet the two games’ personalities are markedly different, so much so that no one who has actually played both of them could ever confuse them. Master of Magic is a gonzo, ramshackle creation, stuffed with so many spells, monsters, treasures, and general flights of fancy that it doesn’t really matter that a third or more of it all doesn’t really work, on a design or even sometimes a purely technical level. Heroes, by contrast, is a much finer honed creation, replacing the fascination of Master of Magic‘s multitudinous sprawl with its own brand of fiendishly addictive playability.

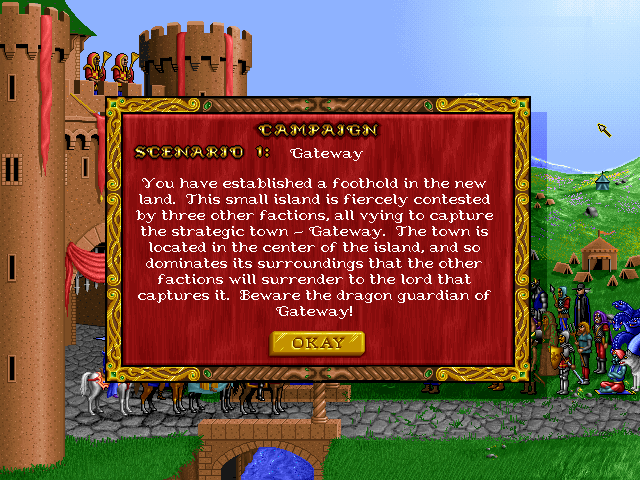

One difference between the two stands out above all the others: while Master of Magic trusts in its random world generator to create interesting dilemmas for the player, Heroes embraces set-piece, human-crafted scenarios. These fall into two categories: there are standalone scenarios you can play — no fewer than 34 of them in the version of the game found at digital storefronts today — and also an eight-scenario campaign which you can play through from the point of view of any of the four factions in the game. This campaign lacks most of the bells and whistles that came in the sequels: each successive scenario is introduced by a bare few sentences of text rather than one of the elaborate cut scenes that came later. As a result, it inculcates little sense of narrative momentum and still less of a sense of identification with the faction leader you’re meant to be playing; if the campaign scenarios had merely been shoveled into the mix as yet more standalone scenarios, no one would likely have been the wiser. Still, it’s a start, the germ of an idea which New World later took to much more ambitious heights.

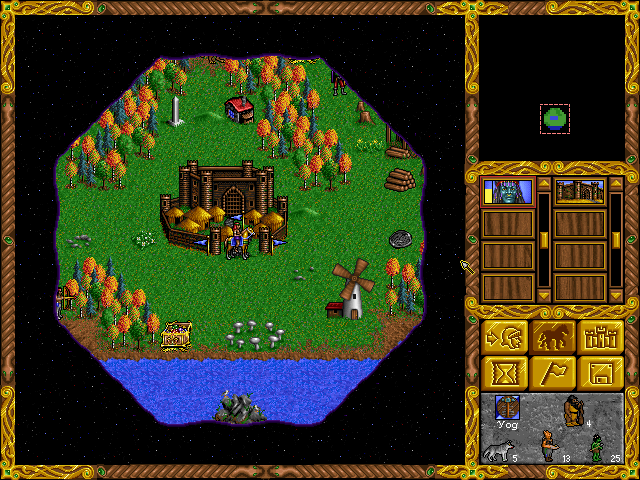

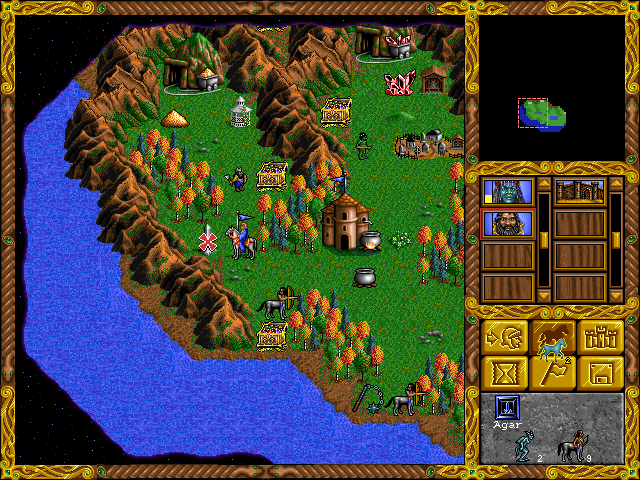

Whether standalone or a part of the campaign, a scenario generally gives you one hero with a few units under his command and one partially developed castle with which to start. Fog of war means that only a tiny portion of the full map is revealed to you at the beginning. In the example shown below, we’ve started as a Barbarian, one of the four possible factions; the others are the Knights, the Sorceresses, and, replacing King’s Bounty‘s Paladins, the Warlocks. One player of each faction is found in each scenario. All of the factions have their own strengths and weaknesses, but in general the Barbarians and Knights are better suited for physical combat while the Sorceresses and Warlocks are better at casting spells.

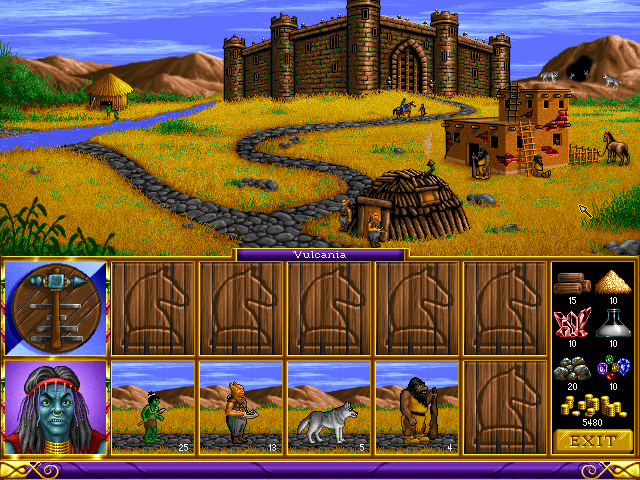

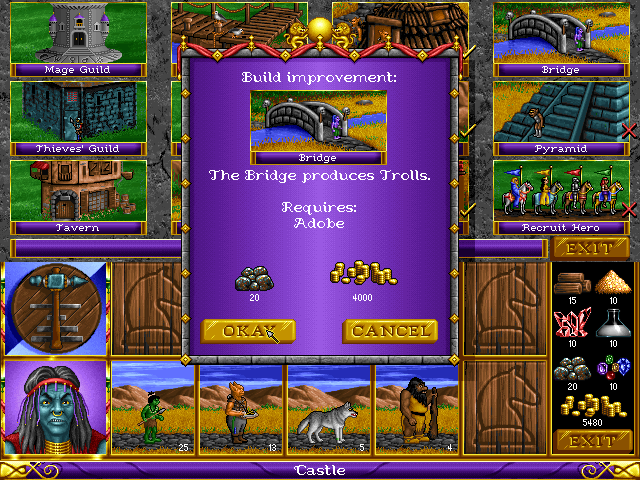

Each of the four factions has its own style of castle, with its own roster of structures to be built up. Each castle can provide different types of units to fight for you — up to six types in all after you build the appropriate “dwellings” for them by spending your gold and other resources. We’ve been given a very generous start here; we already have four of the six possible Barbarian units types — namely goblins, wolves, orcs, and ogres — available to join our legions. Only trolls and the fearsome cyclopes are still to come.

In fact, we find that we have the necessary resources — 20 ore and 4000 gold — to build a bridge that will produce trolls already. A few of the creatures in question become available to hire as soon as a dwelling is built, followed by more at the beginning of every week; each turn consists of one day.

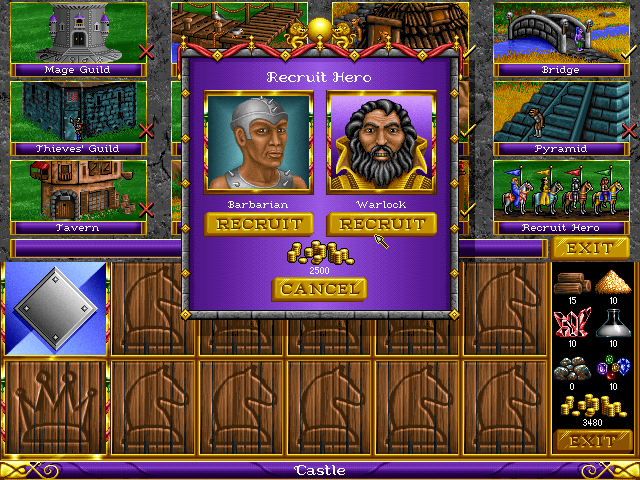

We can also recruit additional heroes at our castles, at the cost of 2500 gold each. Two are shuffled to the top of the pool for our consideration at any given time. Note that, although our starting faction is the Barbarians, we need not confine ourselves to recruiting only Barbarian heroes; nor must individual heroes “follow suit” in terms of the types of units which join their armies, although there is a morale advantage to grouping units of the same faction together.

With money tight, resources scarce, your armies weak, and your heroes unproven, the early game is always a race to scout out as much of the map as possible in order to better understand your strategic position, whilst also grabbing up any loot you find lying about. (Luckily, our Barbarian hero is particularly well-suited to this stage of the game, being the fastest mover of the four types.) There’s so much that is tempting: gold and other resources to replenish our scant stocks, sawmills and mines that can provide a constant supply of resources, magic artifacts which our heroes can carry around to aid them, obelisks which reveal pieces of a treasure map to an ultra-powerful Ultimate Artifact (a legacy of King’s Bounty‘s King’s Sceptre), even some places where we can recruit new units to join our ranks without having to pay for them, as we must at our castles.

But soon the easy pickings around our starting castle have all been scarfed up, and it’s time to start fighting some of the monsters scattered about the map, who guard things that we want and block passes that can take us farther afield. The hero who commands each of your armies is a typical armchair general: he doesn’t fight directly, but rather stays in the rear, adding his Attack and Defense scores to those of his troops, and casting spells that can become devastating by the late game. (For this reason, Barbarians and Knights tend to do best in the earlier stages of a scenario, but can be in for a rude shock if they don’t eliminate their spell-casting rivals before they grow too powerful.) In a testament to the old adage that heroes never die but only fade away, a hero whose army is defeated is merely returned to the pool of his colleagues that are waiting to be hired; if you’re not careful, you might find yourself fighting against a hero who was once one of yours, whom you spent a long time lovingly parenting for the benefit of one of your opponents.

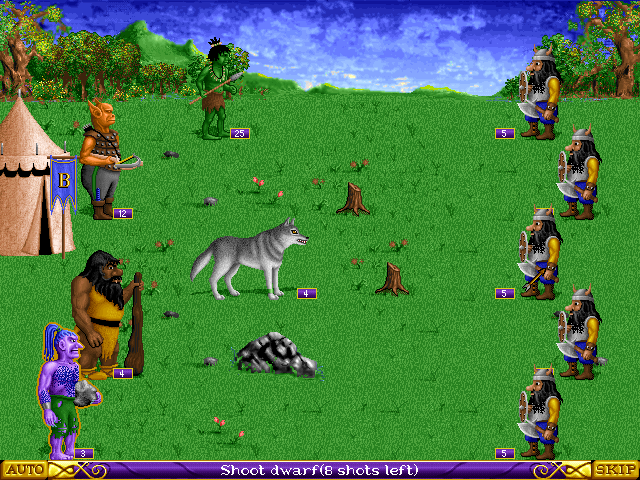

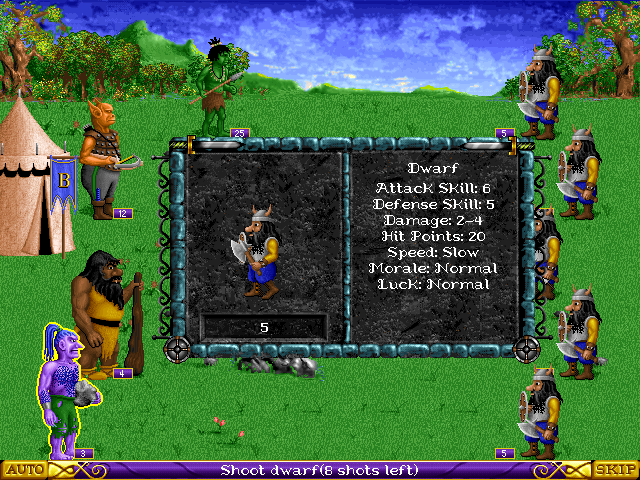

The turn-based combat is as conceptually simple and fast-playing as the rest of the game, but nevertheless boasts surprising tactical subtleties. Each unit type has its own initiative value, movement speed, attack type (melee or ranged), attack potency, armor class, and hit points, and sometimes its own special strengths and weaknesses on top of all of these basic ones. Learning to build and use your armies most effectively, and learning how best to counter the various types of enemies you meet, takes quite some complete games, but doing so is very rewarding.

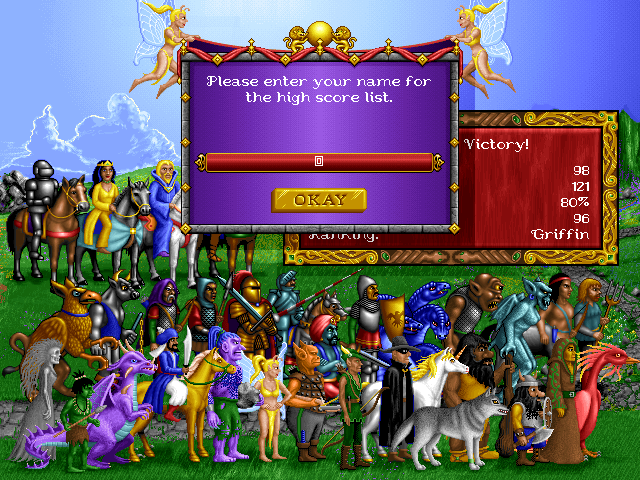

Sooner or later, you’ll come into contact with one of the other players — sooner if you’re playing on a smaller map, later in the case of a larger. Once that happens, exploration begins to compete with military strategy in your ranking of priorities. In most scenarios your goal is simply to capture all of your enemies’ castles, although a few of the campaign scenarios do mix things up a bit by asking you to be the first to recover the Ultimate Artifact or to capture a specific neutral castle. Regardless, Heroes shares with King’s Bounty a quality of brevity that sets it apart from most strategy games of the mid-1990s. Even its largest maps seldom take more than a few hours to explore and conquer. (Of course, this doesn’t mean that you won’t immediately start on another scenario…)

Such is a very, very broad overview of Heroes of Might and Magic. Yet it hardly begins to explain what makes it such a great game. This is every critic’s dilemma: it’s always easier to identify the flaws that keep a given game from greatness than it is to capture that peculiar kismet that yields a game as compulsively playable as this one. Still, it’s part of what I’m paid to do here, so I’ll do my best.

Like so many of the great ones, Heroes is perhaps most of all a tribute to its designer’s willingness to test and test and iterate endlessly until he gets it right. Jon Van Caneghem:

Any time you’re creating a new game — a game that has mechanics people haven’t seen before — there’s a lot of resistance to it. They’re used to something they’ve been playing all the time, and now you’re giving them something new. It’s foreign, so the first reaction is, “I don’t like it.” And if the game isn’t really good, that makes it even worse. If it’s not balanced or it’s not playing right, it becomes, “I don’t like this at all.”

So, my testing department on Heroes was not liking the game. They didn’t like the mechanics; it had a lot of imbalance to it; it was too slow; it was too different. And I just kept hammering at it. I said, “I know this is going to be fun. This is gonna work.” I really analyzed what they were doing and what was bothering them. The length of the turns was too long. If I made the distance that the heroes got to move on the map [in a single turn] too short, they didn’t like it. The same if I made it too long. There was a sweet spot. I made all these little tweaks, and said, “Try it again. Try it again. Try it again.”

All of a sudden, they started getting into it. They started battling each other. Then they started arguing over strategies. That’s my usual moment of clarity in game development. The moment QA is arguing over which strategy is best to win, you’re ready to ship.

This willingness to take every scrap of feedback seriously placed its stamp on every aspect of the game, from the interface, which is as well-nigh perfect as the technology of 1995 could possibly have allowed, to more abstract questions of playability and balance. Consider, for example, the limit of eight heroes per player. Such a number gives you a wealth of possibilities each turn by the late game, but keeps the game’s scope from exploding to the point where keeping track of everything becomes a daunting chore rather than a pleasure, as tends to happen in such predecessors as Master of Magic.

The opponent artificial intelligence is another case study in the ruthless pursuit of fun. It’s a virtual given that the computer will be allowed to cheat somehow in a game of this sort stemming from this era; it simply wasn’t possible at this time to program opponents that could give a decent human player a run for her money on a level field. But instead of merely increasing all of the computer players’ relevant numbers by 50 percent or more, as so many strategy games of the 1990s did, Heroes cheats in a way that isn’t so obviously egregious: its computer players suffer from no fog of war, meaning they know where every resource and castle is on the map from the start and can react accordingly. The resulting competition remains decidedly asymmetrical, but it feels like a struggle against deviously clever opponents rather than blatantly cheating ones. And at the end of the day, the subjective feel of the experience is all that matters. (Then again, if you really want a challenge, you can play against up to three human friends in hot-seat mode, or against one friend over a network. These too are options that surprisingly few turn-based strategy games of Heroes‘s era offer.)

In the final analysis, there is no magic bullet that makes Heroes so much fun, just a long string of small decisions, decided almost invariably correctly thanks to Van Caneghem’s willingness to listen to what his first players told him. The result is a game that’s addictive for all the right reasons — one that’s simple and approachable on the surface but is full of unexpected depths, a possibility space that’s enormously rewarding to explore and learn how to optimize. You’ll feel as if you’re leveling up like one of your heroes as you learn how to play on the Easy scenarios, polish your skills on the Normal ones, and at last find ways to triumph even over the Tough and Impossible ones. You might occasionally slam down your computer’s lid in frustration along the way, but you’ll always come back the next day to try again.

To all of this must be added the game’s immensely appealing presentation, which makes its world a nice place to be even when the tide of war is going against you. One similarity it does share with the CRPG series which gives it its name is its eschewing of the “dark, gritty” aesthetic of so many drearily serious fantasy games of its own era and later ones. Heroes is serious about being fun, but it never takes itself all that seriously in any other sense. Its world is one of bright primary colors that pop right on your monitor screen, of cartoon-style monsters duking it out without ever shedding a visible drop of blood. Its stories and settings don’t make a lick of sense, being a pastiche of whatever mythologies, fairy tales, and pop-culture tropes happened to be lying around the offices of New World. Why do the Sorceress’s glitter-splattered sprites, unicorns, and phoenixes look like an explosion at a My Little Pony factory? And why on earth do cyclopes spring forth from Mesoamerican-style pyramids, and what has any of that got to do with Barbarians anyway? Nobody knows and nobody cares. Heroes succeeds to a large degree through its sheer giddy likability, a reflection of the personality of the man who conceived it. No game less pretentious than this one has ever been made.

Another thing to love about the game is the fact that its roster of heroes consists of women and men in nearly equal proportion. The former are every bit as cool and capable as the latter, without ever being over-sexualized in order to please the male gaze. This level of enlightenment was sadly rare among mainstream strategy games of the 1990s. Heroes stands almost alone in being so welcoming to absolutely everyone.

Complaints? Any critic worth his salt must come up with a few, I suppose. So, I’ll note that some of the more difficult scenarios are as much exercises in puzzle solving as pure strategizing, almost demanding that you fail a few times before you can piece together the correct route to victory. Then, too, despite all the extensive play-testing it received, Heroes is no paradigm of balanced game design by modern lights. The Warlock faction is much more powerful than any of the others. Its top-end units are dragons, the best in the game by far. They have an absurd number of hit points, are completely immune to magical attacks, and can kill two stacks of enemies in one shot thanks to their fiery breath; the first player able to start purchasing significant numbers of dragons is all but guaranteed to win. And Heroes by no means resolves what has long been the biggest conundrum in wide-angle strategy-game design: that of the anticlimactic mopping up that follows that tipping point when you know you’re going to win. The need to optimize your play and weigh every decision carefully — do I spend my precious resources on a dwelling that will produce better units or on an addition to my mage guild that will give me better spells? — goes away after this point. All of the most interesting choices and the most nail-biting drama are front-loaded.

On the other hand, none of these things are necessarily unadulterated negatives.”Solving” a difficult map that’s been giving you fits can be a thoroughly satisfying accomplishment in its own right. And any faction can capture a Warlock castle and thereby gain a pathway to dragons, meaning that the starting Warlock player is most definitely not guaranteed to win — and then as well, the sheer joy of romping across the landscape with a ridiculously overpowered army of dragons shouldn’t be taken lightly when considering these matters. Much the same riposte heads off complaints about the anticlimactic endgame. It usually doesn’t take that long to win once the tipping point is reached, and doing so always warms the heart with megalomaniac joy.

I’ve used the word “addictive” a couple of times already in relation to Heroes of Might and Magic. And indeed, the word seems unavoidable in any review of it. The “one more turn” syndrome these games provoke has long been infamous. I’m not overly prone to gaming addiction myself — unlike some of my friends, I have no stories to tell of playing Civilization or Europa Universalis for 48 hours straight — but Heroes of Might and Magic is the closest thing to my personal gaming Kryptonite. Playing Heroes — solo or, even better, with your friends — is so much fun that it can be downright dangerous to your life balance. I do believe I’ve spent more time with this series than any other in the quarter century since I first encountered it. Heroes is just that engaging, even as it remains hard to explain exactly why. Chalk it up to the ineffability of interactive flow.

Upon its release in September of 1995, Heroes of Might and Magic reaped all of the commercial rewards it deserved. It became the biggest hit in the history of New World Computing to that point, and was pronounced Strategy Game of the Year by Computer Gaming World. His CRPG series forgotten for the moment, Jon Van Caneghem went right to work on a Heroes II, which he would make bigger, richer, and even more addictive than its predecessor. I will, needless to say, be writing about that one as well once we reach that point in our journey through time.

(Sources: the books Might and Magic Compendium: The Authorized Strategy Guide by Caroline Spector and Designers & Dragons Volumes 1 and 2 by Shannon Appelcline; Computer Gaming World of October 1988, November 1990, December 1995, and April 2004; Retro Gamer 49; Space Gamer of August 1981; XRDS: The ACM Magazine for Students of Summer 2017. Online sources include the CRPG Addict’s final post on Might and Magic: Darkside of Xeen, Matt Barton’s interviews with Jon Van Caneghem and Neal Hallford, Julien Pirou’s interview with Jon Van Caneghem, the RPG Codex interview with Jon Van Caneghem, and The Grognard Files interview with Tim Olsen.

Heroes of Might and Magic can be purchased as a digital download at GOG.com.)