A moving train at night is an incredible place to hear stories. Like a campfire.

— Jordan Mechner’s journal, February 24, 1992

I was in Germany once, standing in a train station at night. A train was coming into the station, moonlight glinting off its steel sides. For some reason this image was very vivid to me, and I remember thinking, well, that’s modern European history at a glance.

— Tomi Pierce, 1997

In the years after he completed Prince of Persia and saw it become one of the biggest international videogame hits of the early 1990s, Jordan Mechner did something that one can wish more game designers would find the time to do: he unplugged for a while, leaving games and the sometimes blinkered culture that surrounded them behind as he went off to see the world. From a base in Paris, he traveled extensively throughout Europe. Young, good-looking, rich, talented, and linguistically precocious — his French and Spanish were soon almost as good as his English — he lived “a life right out of Henry James,” as one of his friends told him, whilst lightly supervising his publisher Brøderbund Software’s progress on the Prince of Persia sequel out of his apartment in the Sixth Arrondissement. He was, as he puts it today, “in a rare and fortunate position that few creative artists ever get to experience. At age 28, I was being offered a dazzling array of opportunities to write my own ticket.” Uncertain whether he wanted to keep making games or return to his early dream of becoming a filmmaker, he went to Cuba for several weeks in the summer of 1992, to shoot a twenty-minute wordless documentary about the life of a society 90 miles and 30 years removed from that of the contemporary United States. “I really should make a short film or two before I go after my first big-time feature job,” he wrote in his journal with the blasé optimism of fortunate youth, not pausing to reflect on the reality that most aspiring filmmakers cannot afford to turn their student demo reels over to a first-class Parisian studio for editing and post-production.

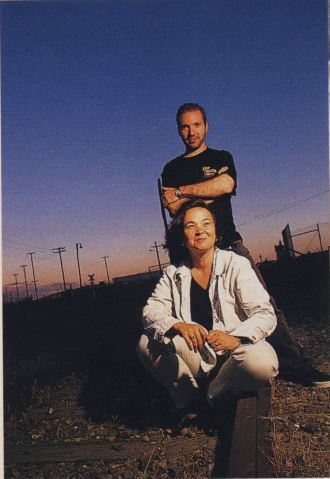

It took an older friend named Tomi Pierce to talk some sense into him. A longtime trusted agent of the Brøderbund management team, she had been instrumental in shepherding Prince of Persia to completion, by alternately coddling and cajoling its moody young auteur through milestone after milestone. She did the latter on a long-distance call from California to France that took place just after his adventure in Cuba. Recharging the batteries was all well and good, she said, but enough was enough. She pointed out how insane it was for a young man who had become a veritable name brand unto himself in one entertainment industry to wish to start over from scratch in another. As she later remembered it, she told him that his life “was a pretentious and pathetic wreck,” and urged him to get hands-on with another game sooner rather than later. Being by no means uncreative herself, she even gave him the stub of a story to start with: “It’s a World War II spy story, and here’s the first sentence: ‘I was taking the night train to Berlin.'”

Those words of hers sparked a four-and-a-half-year odyssey that burned Jordan Mechner’s Prince of Persia fortune right to the ground, ending for the nonce his prospect of living the rest of his life as a globe-trotting dilettante. And he thanked her for it.

Mechner and Pierce were soon talking daily about their game over the transatlantic wire. They decided to move the time period from the Second to the First World War — or rather to just before the First World War, to the summer of 1914, when, almost unremarked by the general public, the dominoes of disaster were falling one by one in Europe. Nothing would ever be the same after that fateful summer; as Barbara Tuchman once wrote, “the Great War of 1914 to 1918 lies like a band of scorched earth, dividing that time from ours.”

But a train would still be the centerpiece of the game. And they knew which train it would have to be: the legendary Orient Express, which left Paris to begin the three-day journey to Constantinople for the last time in a long time on the evening of July 24, 1914. While it was underway, the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia expired, and Europe started the final plunge down the slippery slope to war. Mechner:

Not only did that train cross the very countries that were about to go to war, but at the time, in 1914, it was the very symbol of the unity and financial interdependence of the European countries, kind of like the European Economic Community today. On that train you had a cross-section of all the different segments of European society — all the different countries, all the different political and ideological factions that were about to find themselves at odds.

Needless to say, Mechner and Pierce were not envisioning another cinematic platformer like Prince of Persia. They rather wanted to make a full-fledged adventure game, with a complex story line that did not have to take its cues from the silent movies of yesteryear, as had been the case with Mechner’s previous masterstroke. This was despite — or rather in some ways because of — the fact that Mechner was no fan of adventure games as they were currently implemented, with their fixed plots gated by mostly arbitrary puzzles. He was sure he could do better.

But doing so would require a leap into unknown waters, require him to act as the head of a creative team rather than remaining the lone-wolf coder he had always been before. For better or for worse, those days had ended with the 1980s; Prince of Persia, which shipped on the Apple II three months before that decade expired, had been the last of its breed.

In December of 1992, Mechner visited Brøderbund’s offices near Silicon Valley to iron out some final details concerning Prince of Persia 2, whose release date was fast approaching. He took the opportunity to pitch “the train game” to Doug Carlston, the company’s co-founder (and the future husband of Tomi Pierce).

I’m really excited about this train game. I’ve played all the other adventure games out there, and I think here’s a chance to make something that will blow them all away — not just in terms of story, although that’s a big part of it, but also in the graphic look, sound, music, interface, the way it all fits together — the whole package. I’m talking about a game that will really be a work of art. The first adventure game to have a story and graphics that can stand on their own merits, not just by adventure-game standards.

And I’m thinking beyond just this one game. The train game will take maybe two years to develop, and if it’s the hit I think it will be, there’ll be a major opportunity to follow it up with other games with the same interface, the same special “look and feel.” I want this to be a whole line of games. I’ve been working on this for weeks, and I’m so convinced it’s worth it that I’d be ready to go out and do it on my own as an independent project if I need to.

Look, I’ve spent the last two years traveling and making movies and learning a lot, but basically goofing off. I wouldn’t mind really throwing myself into something for a change. I’d like to risk something. So, emotionally, I’m up for it. I’ve already started looking for an apartment in the city. I want to do this game.

I don’t even like adventure games. But I’m going to do this one. This will be the first adventure game since Scott Adams that I’ll actually like.

Carlston was encouraging, but only cautiously so. He told Mechner that, while Brøderbund would be happy to publish his train game when it was ready, they weren’t prepared to make it in-house or to shoulder all of its development costs. In short, Mechner would indeed have to arrange to make it himself independently, under a standard out-of-house development contract. If he had proposed doing a Prince of Persia 3, the verdict might have been different, but Brøderbund just couldn’t go all-in on such an unproven commodity as this. By way of compensation, Carlston was willing to let Mechner borrow Tomi Pierce for as long as he needed her.

Mechner took Carlston’s words to heart; he would make his train game himself, partially financing it out of his own Prince of Persia royalties, then count on Brøderbund to sell it. He went back to Paris only long enough to arrange a more permanent return to the United States. On January 7, 1993, he moved into his new San Francisco apartment. Five days later, he opened a bank account in the name of Smoking Car Productions, his very own games studio. It was full steam ahead on The Last Express, as the “train game” would eventually come to be called.

The deeper Mechner and Pierce dived into the details of the real time and place in which they’d chosen to set the game, the more they wanted and needed to know. The project became more than just a better take on the adventure genre: it became an exercise in living history. “Authenticity” became its watchword. “And thereby [we] added two years to the project,” says Jordan Mechner wryly.

There are any number of ways that computer games can engage with real history, plenty of which have already been featured on this site over the years. Tactical wargames can let the armchair generals among us refight the battles of the past at a granular level, finding out what might have happened if General Lee had not ordered a frontal assault on the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg or if Admiral Nagumo had not elected to withdraw from the Battle of Midway after losing all four of his aircraft carriers. Meanwhile grand-strategy games can let us explore more abstract questions about economic and political systems, as well as, inevitably, their consequences on the battlefield. But these forms of engagement are more intellectual than empathetic. Another, perhaps ultimately more valuable service games can do us is to drop us right into history in the way of a great historical novel, to let us walk a mile in the shoes of people who are not generals or statesmen, to see what they see and feel what they feel and decide what they do next when faced with dilemmas that may have no easy answers; this last is an aid to immersion and understanding that no static novel can offer us, no matter how vividly written. Such is what Mechner and Pierce now proposed to do: to let their players truly live through a constrained but meaningful piece of history.

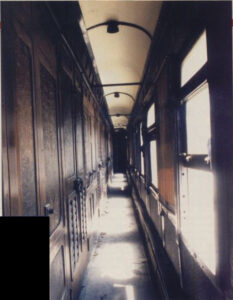

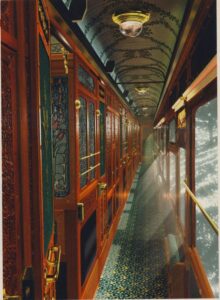

Before they could engage with the bigger issues of the day, they would need to get the nitty-gritty details right, from the angles at which the corridors inside each coach on the Orient Express bent to the way the toilets flushed in the washrooms. Finding these things out was not easy. Although the Orient Express had run between Paris and Istanbul (né Constantinople) from 1883 until 1977, the 1914-vintage carriages were, as far as anyone knew, long gone, excepting only two restaurant cars that were preserved by museums, one in Paris and one in Budapest. Of the interior of the sleeper cars there remained only three photographs. Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits, the operator of the Orient Express, told our heroes that all of their blueprints and other archives from that era had been destroyed.

Imagine their thrill, then, when they got a call one day from a Parisian club of railroad old timers, in response to an advertisement they had placed in a French railway magazine. “The train companies think these archives have been destroyed,” they were told. “We’ve got ’em.”

They agreed to meet at the Gare de l’Est station in Paris, the departure point of the Orient Express throughout its history. (In fact, a train by that name was still running from the station at the time, but it only went as far as Budapest, making rather a misnomer of its appellation.) Tomi Pierce:

Through a door marked NO ADMITTANCE, we plunged into a rabbit warren of offices under the station. In a grimy room at the end of a long corridor, two very old men were sitting at a table. Around them were stacks of boxes.

They had no idea what a computer game was, but as soon as they realized we were seriously interested in their train, they began to talk furiously. For hours, they bombarded us with information, from the exact date when electricity was introduced on the Express to the social structure among train employees of the time. They joked about the frosted glass in the washrooms — not thick enough to completely conceal the occupants. They sorted through the boxes, pulling out irreplaceable original materials. Passenger lists, menus from July 1914, detailed floor plans, conductor’s rule books — a thousand features of the train were documented. As the old men talked, the Orient Express seemed to rise in ghostly form. “Use it all,” they said a little sadly. “No one else ever will.”

We felt a responsibility to do the right thing. If you listen to these old trainmen — well, they love trains and their history. I thought about their apartments at home, filled to the brim with old train archives they had saved themselves. And when they die, that knowledge is probably gone forever. So, you feel an obligation to them to get it right.

At the end of that interview, they asked if we would like to see their train set. Directly under the central platform was a room the size of a basketball court, filled with the largest train set I had ever seen. Every period of train history was represented. All the train-car and engine types, wide- and narrow-gauge rails, signals and tracks were hand-built. The model-train network had been under continuous construction by the employees at the Gar de l’Est for the last 40 years. Our guide shrugged. “It’s just to amuse ourselves,” he said. “It is… for our pleasure.”

Pierce resolved then and there to turn The Last Express into an exercise in “electronic archaeology”: to “recreate that train and the drama of its time using every high-tech trick we knew.” Mechner:

I mean, you can legitimately ask, “Who cares? What does it matter which way the sleeping car faced?” But there’s something about a piece of history on the verge of being forgotten. Whatever else you can say about this game, it’s authentic.

Word of these crazy Americans who wanted to recreate the Orient Express on a computer screen spread among the trainspotters of Europe. One day they received an unsolicited note from an Italian gentleman: “There is a 1914 Orient Express sleeping car in Athens. It is in dilapidated condition and is not in working order.”

It turned out to be just sitting there right where he said it was, shunted to the side of a railway depot on the outskirts of the city. Unlike the restaurant cars in Paris and Budapest, both of which were maintained as museum pieces with rigorously enforced rules of access, this car was open season. From Jordan Mechner’s journal:

Two days in that sauna of a busted-down Wagon-Lits car, baked by the sun for the past 50 years, or however long it’s been sitting there. Kicking aside debris, sending up clouds of dust, covering the windows with sheets to try to cut down the contrast, sweating, snarling at each other, and generally getting to know that car more intimately than we ever could have if it had been in good condition with an official keeping an eye on us, like the one in Budapest.

They documented every inch of the carriage in pedantic detail. “The colors in the painted ceilings, the mechanism of opening the bed bunks, the tooled leather of the walls, the pattern in the carpet,” wrote Pierce later. “We studied it all.” With the cockiness of youth, Mechner wrote in his journal that “I think we can now safely say that we know more about the 1914 Orient Express than any one person living.” Now they just had to move all that knowledge into the computer.

Extracts from the “Making Of” video included on The Last Express CDs.

Shortly after returning from Athens in August of 1993, Mechner made a pivotal decision. As a Brøderbund insider, he’d been watching with considerable interest the progress of an adventure game called Myst, which Brøderbund planned to publish on the Apple Macintosh the following month. Although his design goals for The Last Express were in many ways far more ambitious than those of Myst, he loved the sense of immersion fostered by its first-person, pre-rendered 3D environments. It seemed the way to go with his game as well. But, as he admitted in his journal, “I know almost nothing about this.” To remedy that, he flew out to Spokane, Washington, to spend several days with the Miller brothers of Cyan, Incorporated, the masterminds of Myst. He even wondered whether it might be possible to hire one or both of them for his own company. In a year or two, the huge success of Myst would retroactively make this musing sound hilariously presumptuous. At the time, though, it must have seemed perfectly reasonable. After all, he was an established auteur with one of the biggest franchises in gaming on his résumé, while the Miller brothers were just a pair of refugees from children’s software trying to make a go of it with the big boys.

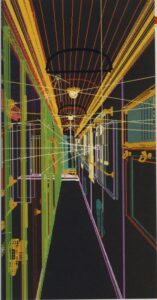

In lieu of the Miller brothers, Mechner wound up hiring his own team of 3D modellers and programmers to bring the Orient Express to life. The watchword remained authenticity, down to the literal last screw. The textures in the carriages were pulled directly from photographs of the cars in Paris, Budapest, and most of all Athens: “green velvet upholstered benches, stamped-leather wall panels, flowered ceilings and brass rails. The train that appears onscreen in The Last Express hasn’t been seen in 80 years,” wrote Tomi Pierce.

Indeed, the game has almost a unique claim to historical authenticity. The wargames that the grognards love may wish to think of themselves as infallible “simulations” of events in time, but their what-if scenarios hinge on their designers’ own all-too-fallible interpretations of the events they purport to simulate. The recreated interior of the Orient Express, however, is dependent on no one’s interpretation. It’s simply a copy of the real thing, implemented as meticulously as the technology of the 1990s would allow by people with no allegiance to anything but the truth of their cameras and measuring tapes.

But of course, there had to be more to the game than its environment. The recreated Orient Express was to be the stage for a work of historical fiction, a complicated caper taking place on the train’s last voyage before the Belle Époque ran out, Europe descended into four and a half years of war, and a new twentieth century full of unprecedented wonders and horrors got going for real.

Historians are divided into two broad camps when it comes to the origins of the First World War: the powder-keg school, who see the Europe of the time as just waiting for a spark to start an inevitable conflagration, and the bad-luck school, who see a thoroughly evitable war that came at the end of a long string of random unfortunate events. It’s probably for the best that The Last Express doesn’t take a firm position either way. Rather than whys, it’s interested in how it was to be in Europe just before the Old was swept away forever by the New. Aboard its version of the Orient Express are German industrialists, Russian aristocrats and anarchists, Serbian separatists, Austrian and British spies, French engineers and bohemians and socialists, a Persian harem, even an enigmatic, fabulously wealthy North African “prince.” Unlike the train itself, which is scrupulously realistic, the cast of characters aboard it reflects a sort of hyper-realism; all are, whatever the other details of their individual personalities, archetypes of the social currents swirling around Europe at the time. The only group missing — albeit necessarily so, given the opulent setting — are the unwashed masses who would soon be expected to fight and die in the name of their betters.

There’s something about a train, a circumscribed space rushing inexorably through a landscape from which its occupants are isolated, that’s irresistible to lovers of romantic intrigue. It’s a locked-room mystery, only somehow even better, combining claustrophobia with exotica; small wonder that trains figure so prominently in the classic-thriller canon, from Agatha Christie to Alfred Hitchcock to Patricia Highsmith.

In this iteration on the template, you play Robert Cath, a debonair American doctor who boards the Orient Express in rather… unusual fashion just as it’s pulling out of Paris. He’s responding to a summons from an old friend, a fellow American named Tyler Whitney, whom he now finds dead in their shared compartment, apparently the victim of cold-blooded murder. Cath dares not draw attention to himself because he is sought by the police for some antics he may or may not have gotten up to recently with some Irish terrorists/freedom fighters, so he disposes of the body and assumes his friend’s identity, as you do in such situations. Soon he finds that Tyler, a heedless idealist of the sort that tends to cause an awful lot of trouble in the world, was up to his eyebrows in a complicated conspiracy to sell arms to Serbia’s Black Hand, the terrorist group responsible for the recent assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, an act destined to go down in history as the spark that ignited a world war. And then there’s the strange Russian artifact known as the Firebird that’s been stolen out of his friend’s luggage…

But I won’t spoil the story for you. Trust me, it’s worth experiencing for yourself.

A Digression on Being and Time

Let’s pause here for a moment to consider adventure games’ fraught relationship with time. In fact, let’s go way back, to before Myst, before point and click, before even graphics and sound, to a time when all adventure games were text adventures. The earliest of these were treasure hunts: thin quest narratives in which you roamed a static world that changed only when you did something to make it change. Your only goal was to explore and solve puzzles in order to collect treasures, for which you earned points by depositing them back in some safe place. Sure, the introduction to the game might attempt to provide some more noble justification, but that was more or less the gist of it. Once you had all the treasures, you also had all the points and you were done.

But within a year or two, people began to chafe at the limitations of worlds frozen in amber, itched to create real interactive stories where characters and things moved and changed around you independent of your own actions. Scott Adams, the very first man to put a text adventure on a mass-market microcomputer, gave it a shot already in 1979 with an unusual effort called The Count; Roberta Williams, who with her husband Ken was the first to add illustrations to the text adventure, made some more gestures in that direction the following year with Mystery House. But the folks who really moved the needle, here as in so many aspects of the craft of adventure, were the ones at Infocom. In 1982, Infocom’s Marc Blank gave us Deadline, a full-on interactive mystery, taking place in a mansion whose inhabitants moved about and acted on their own accord, challenging you as the detective to figure out what they were up to if you wanted to survive the day, crack the case, and bring the guilty party to justice. Instead of exploring a landscape, it asked you to explore a dynamic possibility space.

Yet there was a big drawback to this approach: the game could and usually did run away from you. If you didn’t happen to be in the right place at the right time to answer the telephone or to intercept the postman, you were just out of luck; the crime was doomed to go unsolved. The only way to beat Deadline was to play it over and over again, gradually putting together where you needed to be when and what you needed to do there. Only then could you make your winning run, where everything just kind of worked out for you in the way it always seems to for Hercule Poirot on the very first try.

In the abstract, it’s as valid an approach to game design as any other. Yet if we’re wedded to the idea of an adventure game as an interactive fiction — as a lived story — rather than a mere meta-puzzle, it can feel deeply artificial and unsatisfying. In a game like Deadline, relatively small and quick-playing and implemented entirely in text, it’s perhaps more agreeable than in one of those later multimedia extravaganzas that force you to watch the same interminable cut scenes again and again. Still, even Infocom learned pretty quickly that their customers didn’t much care for it. Each of the two dynamic mysteries they released after Deadline sold worse than its immediate predecessor, causing them to give up on the approach.

For the fourth Infocom title with the genre label of “Mystery,” 1986’s rather obscure Ballyhoo, author Jeff O’Neill tried something different. Ballyhoo is the first adventure I know of to fully embrace plot rather than clock time. That is to say that events unfold in the rundown circus that is its setting not in response to passing turns but in response to your progress through the plot. As I wrote in my review of Ballyhoo years ago, it “flips the process on its head: makes the story respond to the player rather than always asking the player to respond to the story. Put another way, here the story chases the player rather than the player chasing the story.” As you solve puzzles and make progress, the world rejiggers itself to accommodate the next phase of the story it wants you to live through. Of course, this is not playing fair by the objective rules of simulation. No matter: O’Neill grasped that the player’s subjective experience of an interactive story is what really matters in the end. The approach was adopted by a great number of later adventure games, many of them far less obscure than Ballyhoo — perhaps most famously of all by Jane Jensen’s plot-heavy Gabriel Knight graphic adventures of the 1990s.

Yet plot time can produce pitfalls of its own. Anyone who has ever played a Gabriel Knight game is familiar with the frustration of trying to end the day: of running hither and yon through the world, clicking on everything and talking to everyone for the umpteenth time, looking for that hidden trigger that will satisfy the conditions for grinding the plot gears forward to another evening, so that Gabriel can go home and go to bed and wake up to another morning and the next phase of the story line. This sort of plot stasis can be almost as infuriating as a plot that has run away without you; when you’re caught up in it, it can pull you out of the fiction every bit as much. And then, too, the very notion of plot time philosophically bothers many a player and designer, who see it as a sort of betrayal of the very premise of an adventure game as a living world, one that ought to be allowed to go about its business without any such thumbs on its scales.

Count Jordan Mechner and Tomi Pierce among this group. While they couldn’t make their game run in literal real time — it would have been impossible to implement that much content, and quite probably deadly boring for the people who experienced it — they did want it to run in an accelerated version of same, such that the three-day trip to Constantinople would take about five hours of playing time. The other passengers and crew on the Orient Express would move about and pursue their own agendas during those hours, even as the train itself chugged relentlessly onward. All of this would happen no matter what Robert Cath chose to do with himself. Lead programmer Mark Moran:

We created a language where every character has a script. They all have their motivations to drive the story forward. At 8:00 PM, August Schmidt goes to dinner, and has dinner until 8:30. He’s hoping he might run into you at dinner, but if he doesn’t he might see you from 8:30 to 9:00, when he’s in the salon smoking. At 9:30, he’ll grow frustrated and come to your compartment and knock. He’s got a long list of instructions. We created this language where we could write the instructions for every single character.

There would be no patently manufactured drama in The Last Express; if, say, a group of police officers boarded the train to look for a suspected American terrorist, they wouldn’t wait until Cath found the perfect hiding spot before bursting into his cabin. Instead they’d burst in when they burst in, let the chips fall where they may.

And yet it remained an incontrovertible fact that adventure gamers hated sudden deaths and especially walking-dead situations, as it’s called when you’re left wandering around in a game which you can no longer win, often without even knowing that that’s the case. They hated these things so much that LucasArts had built an immensely successful adventure empire out of promising players that they would never, ever put them in that position, no matter what they did or didn’t do. Clearly a simple reversion to clock time alone wouldn’t do for The Last Express. Out of this dilemma sprang the game’s biggest formal innovation: it would have no conventional save command at all. Instead it would let you rewind time itself to some earlier point whenever you wished, as if you were rewinding a videotape of your actions, and pick up again from there. Meanwhile the forward progress of the plot, chugging constantly onward like the train itself, would ensure that any conceivable walking-dead situation couldn’t drag on for very long. Once you died or blundered into some other bad ending, the game would automatically rewind the story to the last point where victory was possible and let you try again. In this way, The Last Express would preserve the integrity — or, if you like, the authenticity — of its storyworld, without driving its players crazy.

Smoking Car would also eliminate the artificial set-piece puzzles that were the typical adventure game’s bread and butter, offering up strictly situational challenges instead that were inseparable from the story: hiding Tyler’s body in your cabin, hiding from the police, figuring out just why that beautiful and famous Austrian concert violinist seems to want to kill you. Needless to say, alternative solutions would abound. Jordan Mechner:

A traditional rule of dramatic construction is that, if you put a gun on the wall, it must go off. In a game, if someone mentions their birth date in a conversation, you’re supposed to write that down, because it might be a combination to a safe. The Last Express deliberately breaks that rule. We just didn’t want to do that. The Last Express is gentler than most adventure games, because the things you have to do to win are not that hard to figure out. It’s what fills the spaces in between that makes life on the train interesting. (Or real life, for that matter.) Anyone who plays The Last Express is going to get drawn in listening to a particular conversation, or reading an article in the newspaper, and miss other events that are happening at the same time. And it’s all okay. You aren’t punished, you don’t miss a crucial clue or get dumped into another story branch. You just have a different experience.

Does the finished game live up to this billing? Not entirely, I must say. The fact is that there are dead ends in The Last Express — how could there not be with such an approach? — and the auto-rewind function, useful though it is, can still leave you replaying substantial chunks of the game, hoping to find a way to progress past the stumbling block this time around. In short, and in direct contradiction to Mechner’s statement above, there are “vital clues” which you can and probably will be “punished” for missing.

In the end, then, I have mixed feelings on this idea of clock time with rewind. I fear that Smoking Car may have violated one of Sid Meier’s principles of game design: that it’s the player who should be the one having the fun, not the programmer or designer. Yes, it’s neat to think about 30 different characters moving about the train pursuing their own agendas, and it was surely exciting to implement and finally see in action. But how much does it really add to the ordinary player’s experience? Ironically given its formal ambitions in other respects, The Last Express has just one story to tell at the end of the day; there’s only one “winning” ending to contrast with the eleven losing ones where Robert Cath doesn’t complete the trip to Constantinople for one reason or another. Would a cleverly designed plot-time structure have been so bad after all? It would definitely have been easier to implement, shaving some time and some dollars out of an extended and expensive development cycle.

But, lest I sound too harsh, let me also say that experiments like this one are necessary to tell us where the limits of fun and frustration lie. If The Last Express proved a road not taken by later adventure designers for a reason, that makes it only all the more valuable a case study to have had to hand.

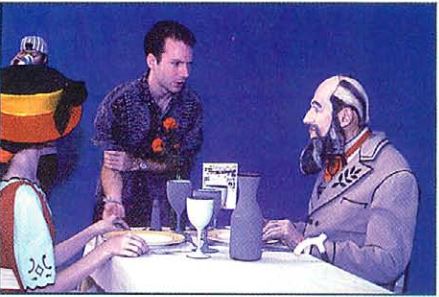

Like Myst and countless other adventure games of its era, The Last Express blended its computer-generated environments with real human actors. But it did so as it did all things: with a twist. In September of 1994, Smoking Car Productions began a three-week film shoot, just like about a million other game projects seemed to be doing at the time. Yet instead of crudely and incongruously overlaying undoctored digitized images of the actors onto their 3D-modeled scenery, they used only their outlines, coloring them in by hand like comic-book art. It was, one might say, the logical next step for Jordan Mechner, who had filmed his little brother running around a New York park back in the 1980s, then laboriously hand-traced his outline frame by frame on his Apple II in order to give his Prince of Persia a more lifelike sense of movement than just about any other figure ever seen on an 8-bit computer. In this new context, though, it was labor intensive on a whole different scale, adding an incalculable number of months and dollars to the project. Never mind: it had to be done, for there was no appetite for compromise at Smoking Car Productions.

Jordan Mechner with two of the actors at the film shoot. “They were garish costumes, purple and orange, just the gaudiest things,” remembers Mark Moran. “A jacket would be purple on one side and orange on the other so that the computer would be able to tell where one flap met [another]. Every single line was a big piece of felt. They looked almost like cartoons when they were on set. It was very hot because you’re caked in theatrical makeup and you’re wearing these wigs that accentuate the colors in your hair, so the computer can find those and highlight a curl or a parting…”

This applied equally to the sound design. A team of voice actors, mostly not the same as the onscreen ones, was hired to voice dialog in English, French, Russian, German, Arabic, Turkish, and Serbo-Croatian. All had to be native speakers for the sake of authenticity. “Casting American actors who can do a fake German or French accent just wasn’t acceptable to us,” says Mechner. Luckily for the player, Robert Cath was written as a rare American polyglot, much like Jordan Mechner himself. Those languages he could understand — the first four of those listed above — were subtitled in the game. The others were left a mystery to the player, as they were to Robert — but if you the player could happen to understand one or more of those other languages, you would realize that these dialogs too made perfect sense.

Originally projected to take two years and $1 million to make, The Last Express ended up taking four years and $5 million. (If we add to the timeline Mechner and Pierce’s earliest design discussions, we end up at almost exactly the length of the First World War itself…) Tomi Pierce:

In October 1994, we were 15 people; by December we were 28; by July 1995, 50 leather-jacketed nerds, spread over four offices, were working 70-hour weeks. Smoking Car had become a bustling thought factory. The 3D department created thousands of train interiors. The art department created and processed 40,000 frames of animation. The programmers built animation tools as well as the game structure. We worked on sound and film editing. Additional dialog recordings in French, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, and German created a rich sonic tapestry. A Czech film-music composer wrote and scored a beautiful soundtrack for the game. By 1996, we were running 24 hours a day; people were sharing computers in shifts. We became a major patron of delivery pizza; everyone was either losing or gaining quite a bit of weight.

We missed our first, second, and third product deadlines. Since our cash advances were tied to achieving these milestones, we stretched payables and everyone went on half salary; the tension and stress increased.

Now a year behind schedule, we finally assembled a fully playable version of the game. This is called beta: the point when, like Frankenstein’s monster, all the parts of the body have been hooked up, and it begins to breathe and open its eyes. Play testing began at Brøderbund. Its testers played the game over and over for months, attempting to break it by finding flaws in the design. Every time it crashed, our programmers fixed the weak point… and the process began again. In three months, more than 5000 bugs were logged. All of them got fixed.

February 1997: we were done.

The calm was deafening. One night we all sat down and played the game together for the first time. It seemed to have a life of its own. We were thrilled and humbled to see the strange, living drama we had made — this odd new marriage of story and technology. It may seem counterintuitive, but computer software is in many ways a handicraft business.

Most people who have worked on a large-scale creative project are familiar with the vaguely unnerving, anti-climatic quiet that follows such a project’s completion, that feeling of “Now what?” that marks the time between production and reception. If all goes well, that period of yawning calm is a short one, soon to be replaced by slaps on the back and bonus checks as the sales reports roll in, the belated rewards for a long, hard job well done.

But that wasn’t what happened this time. Brøderbund sent The Last Express out the door with a $1 million marketing budget, and Tomi Pierce even managed to secure a four-page feature on its making in, of all places, Newsweek magazine — hardly an obvious outlet, but emblematic of everyone’s hopes that this interactive story could generate interest well beyond the usual gaming circles. (I’ve quoted liberally from her article here.) And then… crickets. The Last Express flopped like a pancake on a cold linoleum floor.

To my mind, the saddest document in the Jordan Mechner archive at the Strong Museum of Play is an email from him to Brøderbund’s marketing department, dated July 7, 1997. In it, he pleads with Brøderbund not to give up on his baby, not to lower the price and consign all remaining copies to the bargain bins, that graveyard of game developers’ hopes and dreams. Instead he asks them to gird their loins and pour another $1 million into a second marketing campaign. One of the section titles is, “Why we still think Last Express can sell 1 million units.”

Last Express does not appeal primarily to adventure gamers. Its target market is adults, 18 to 44, both men and women, college-educated professionals pre-disposed to purchasing sophisticated, intelligent entertainment. An informal survey of the reviewer and user response to the game shows that we are scoring high with the non-adventure-gamer audience — in particular, with the adult female audience that the entire industry is trying to figure out how to reach. Diana Griffiths and other reviewers have singled out The Last Express as one of the rare games that appeals to intelligent adult women.

People rave about the game for a variety of reasons — the story and characters, the lack of “gaminess,” the sense of “being there” — but they all seem to agree on one thing: Last Express is different. Like Myst, it will probably have limited or partial success within its genre (adventure games), but will ultimately succeed with a much wider audience of non-gamers and non-adventure gamers (i.e., gamers who do not usually play adventure games).

One doesn’t have to read too much between the lines of this missive to recognize that even Mechner doesn’t really believe his arguments will find traction at Brøderbund. He had always had a good relationship with his publisher’s management staff, but they hadn’t gotten where they were by beating dead horses. They were especially unlikely to do so now, given what they had waiting in the barn for release that Christmas season: Riven, the long-anticipated sequel to Myst, the closest thing to a guaranteed million-plus-seller that a softening adventure market could still produce. It made no sense to divide their Christmas marketing energies between two different adventure games and risk fatally confusing the public. So, by the time Riven appeared in stores, The Last Express was already long gone from them, written off as one of the costs of doing business in an unpredictable creative industry. It deserved a better fate.

Mind you, I don’t want to overstate the case for it. Even when setting aside my reservations about clock time with rewind, The Last Express falls short of perfection. Indeed, I think most players would agree that one part of it at least is downright bad. There are about half a dozen places where Robert Cath can get into fisticuffs or knife fights, implemented via a little action-oriented mini-game. I appreciate the sentiment that lies behind them — that of dropping the player right into the action — but that doesn’t change the fact that these places where The Last Express suddenly wants to be Prince of Persia are awful. The controls are sluggish and feedback is nonexistent. They devolve into pushing the mouse about randomly and clicking madly, until you stumble upon the rote combination of moves that will let you continue. It’s hard to imagine anything more off-putting to the audience of non-hardcore adults that Mechner believed the game to be capable of reaching.

Then, too, we’re still stuck in the old Myst interface paradigm of the first-person slideshow game. It’s seldom clear where you can and can’t look or how many degrees you’ll turn when you rotate, making it weirdly easy to get confused and lost inside the train, despite it being about the most linear space one could possibly choose to set a game.

That said, it would take a much stricter critic than I to say that these weaknesses outweigh all of The Last Express‘s strengths. It’s thus unsurprising that so many extrinsic reasons have been floated for the abject commercial failure of The Last Express, by both the principals involved in making it and by the game’s fans. Some of these are dubious: the claim that Smoking Car’s inability to finish the game in time for the 1996 holiday season was the culprit is belied by the existence of other games, such as that very same year’s mega-hit Diablo, which likewise missed the silly shopping season and did more than fine in the end. And some of them are flat-out wrong: Brøderbund’s acquisition by the edutainment giant The Learning Company had nothing to do with it, given that said acquisition occurred fully a year and a half after the game’s release and subsequent washout.

Sooner or later, most arguments tend to fall back on blaming gamers themselves for not being “ready” for The Last Express in some way, as Jordan Mechner is already beginning to do in the email above. In 2021, for example, Mark Moran said that the unusual setting didn’t “resonate” with American gamers. I must admit that I’m not entirely unsympathetic to such sentiments; I have nothing against dragons and spaceships in themselves, but I’ve often wished — and often on record right here — that more games would dare to look beyond the nerdy ghetto and embrace some more of life’s rich pageant. Nevertheless, in the world of games, fantasy and science fiction have always outsold realism, and this seems unlikely to change anytime soon.

And really, there’s not much more to be said on the subject beyond that; audience blaming is always a counterproductive pursuit in the long term, for the critic every bit as much as it is for the artist. The Last Express simply didn’t tickle the fancy of existing gamers. And meanwhile, for all that some of the readers of Newsweek may have found the article about the game to be interesting, very few of them found it interesting enough to venture into the unfamiliar space of a software store to pick it up. One does suspect that, if they had, they would have found the game fairly incomprehensible: The Last Express actually expects quite a lot from its player; by no means it is a “casual” game. Its combination of subject matter and gameplay approach meant it was always destined for niche status at best.

After its rejection by the marketplace, Jordan Mechner quietly closed down Smoking Car Productions, retrenched and regrouped, and jumped back on the horse he’d rode in on. His next game was 2003’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, a massive worldwide smash that recouped all the money he’d blown on The Last Express and then some, making him once again a very wealthy man. He elected not to squander his second fortune on any more esoteric passion projects. And who can blame him? The Last Express is the sort of crazy creative gamble that most commercial artists dare to take only once in their lives.

Still, you didn’t have to look too hard at The Sands of Time to see that his train game was still exerting an influence over him: the new game’s central innovation, which a new generation of critics were soon elbowing one another out of the way to praise and analyze, wasn’t really as big an innovation as most of them believed it to be, being a rewind mechanic similar to the one found in The Last Express. Transplanted into a platforming action-adventure, it actually felt far more natural. This, folks, is how game design inches forward.

Alas, Tomi Pierce, who gave as much of herself to The Last Express as the man whose name featured so prominently on the box, never got to play an equally pivotal role on any other game. She died in 2010 of ALS. “A bright light has gone out but continues to sparkle in our memories,” wrote Mechner in memoriam. “We miss her terribly.”

On a happier note, The Last Express lives on today as a cult classic; it’s even been ported to mobile platforms. Some years ago now, I quoted Infocom’s Jon Palace in praise of Steve Meretzky’s A Mind Forever Voyaging (a game that, come to think of it, occupies a similar place in his career as The Last Express does in Jordan Mechner’s). Palace’s words have just come back to me unbidden as I write this conclusion: “For me it was, like, ‘Great! Look, we can really elicit an emotional response!’ — an emotional response which isn’t trite. That for me was the best.”

There is nothing trite about the thoughts and feelings The Last Express will stir up in you if you meet it with an open mind. More than just a labor of love, it’s a true work of interactive art as well as an evocative work of history, a long-vanished world brought to life just as it was the instant before it passed away.

Where to Get It: The Last Express is available for digital purchase at GOG.com for Windows computers, at The Apple Store for iOS devices, and at Google Play for Android devices.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III, The Making of Prince of Persia by Jordan Mechner, The Last Express: The Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba, The End of Books — Or Books without End?: Reading Interactive Narratives by J. Yellowlees Douglas, and The Guns of August and The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World before the War, 1890-1914 by Barbara Tuchman. Computer Gaming World of January 1997 and July 1997; Retro Gamer 112, 118, and 216; Edge of February 2011; Newsweek Special Issue for 1997; Next Generation of January 1997; PC Zone of June 1997. The Jordan Mechner archive at The Strong Museum of Play was invaluable, as was the wealth of material to be found on Mechner’s personal website.

Sarah Walker

October 6, 2023 at 5:23 pm

Not a game I’ve ever played. However, it’s noteworthy (to me at least!) in that it’s the only time I’ve seen a games magazine outright apologise for a review. PC Zone reviewed it on original release, giving it 72% in a very short, almost content free review. Come issue 66, just over a year later, Paul Presley (the reviewer in question) pops up in the Feedback section, apologising for his original review, saying he would on revisiting it now give it 95%, and encouraging Brøderbund to give it another marketing push. Needless to say it was far too late by that point…

PlayHistory

October 6, 2023 at 5:45 pm

One thing I find interesting about Mechner’s compulsion to do a take on the Orient Express with simulation-esque realism is that Will Wright was looking to do the same with the Hindenburg at this exact time. And I believe one of those Titanic games fits into this mix too. Perhaps it’s just a fallout from the promise of multimedia, but it did mean that for a time there was an exploration of more historical settings rather than genre fiction.

The Last Express is one of those necessary leaps of faith to see what ultimately would not work within a new paradigm. I don’t agree with all of your takes on how adventure games should be, but in this period of rapidly evolving technology mixed with declining interest in the format, it’s clear that it got off course. It’s a great example of ambition skipping ahead of market realities and the crucial role that a producer plays in handling someone like Mechner.

I do greatly appreciate Jordan for being that guy. He has three stone-cold classics under his belt of different genres and different eras, and even managed to experience his great dream of writing for a blockbuster picture. It really is the great auteur dream and he’s never left anyone – as far as I know – cold in his wake. Upstanding guy and – if we need to have one game author who’s “a pretentious and pathetic wreck” I’m glad it’s him.

Jimmy Maher

October 6, 2023 at 6:58 pm

Cyberflix, the makers of Titanic: Adventure Out of Time, planned to make a whole series of similar games at one time. I believe the Hindenberg was to be the subject of the next one, but the owner of that studio saw how the adventure market was fading and decided to take the money from the fluke success of the Titanic game — entirely thanks to the movie, of course — and run.

There are some striking points of similarity between Titanic and The Last Express: deeply researched historical setting, take place in vehicles, same time period, superficially Myst-like interface with very non-Myst approaches to gameplay, experimentation with new approaches to dynamic plotting. I actually tried to work Titanic into the article, but it just wasn’t fitting. For the record, though, the big difference between the two games is just that The Last Express is so much better: vastly better written, evincing a much more nuanced understanding of history, with none of those awkward lapses into comedy that Titanic and so many other adventures can’t seem to resist. But this opinion is more a case of praising The Last Express for rising above the usual standards in these departments than criticizing Titanic; the latter isn’t a bad little game at all.

Marco

October 7, 2023 at 12:29 am

I’ve played both games inside-out and simply can’t agree with you on that particular point – you can of course disagree with me but just to point out there are different perspectives here.

The core thread of Titanic: AOOT is The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, its meaning not just its presence as an object to retrieve. It really gets uncanny how the lines of the poem, the facts of the ill-fated ship, and the plot and characters of the game all seem to interweave.

The Last Express does something a bit similar but with a made-up Russian legend, one that takes the game rather incongruously into the supernatural, given the precise realism on everything else.

Rowan Lipkovits

October 6, 2023 at 5:54 pm

“His next game was 2003’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time”

Would be nice to get a sentence acknowledging the Prince franchise’s connective tissue of Prince of Persia 3D, on which Mechner is credited but presumably had little to do with, bridging The Shadow and the Flame with the Sands of Time. But it would add little to your main narrative thrust there, indicating Sand’s direct inheritance of the rewind from Express.

PlayHistory

October 6, 2023 at 6:38 pm

I have stated my hope that Jimmy will do an entry all about the graceless transition to 3D for franchises like King’s Quest, Ultima, Monkey Island, and Prince of Persia. That would be a better context to discuss it, I think.

Jason Dyer

October 6, 2023 at 5:54 pm

>Ballyhoo is the first adventure I know of to fully embrace plot rather than clock time.

The earliest I can go is The Black Sanctum (1981) which has a kidnapping and snow piling blocking the cabin you’re in both timed on the player’s actions rather than some overall timer.

One curious variation I played recently was the weirdly ambitious Adventure 200 (1982) which had a big chase sequence but all reactions were based on the player’s location. So you could theoretically pause in a room while guards were chasing and they only continued when you moved to the next room sequentially. This seemed to be mostly a technical hack (and not a design finesse like Black Sanctum did) but it was still fascinating in context.

Alex Smith

October 6, 2023 at 6:17 pm

Great article as always. I come down on The Last Express the same way you do, an utterly charming premise imperfect in its execution. I want to love it more than I do, because I certainly adore the idea of it.

One tiny nitpick for you. As Jason Dyer has pointed out to me when I made the same error, Scott Adams was not “the very first man to put a text adventure on a microcomputer.” Gordon Letwin’s port of Adventure, while far more famous in its Microsoft iteration, was first available on Heathkit micros by August 1978, just edging Mr. Adams and his Adventureland.

Jimmy Maher

October 7, 2023 at 9:06 am

Yeah… I’m sure you’re literally correct — I may even have known that at one time — but, comparing the impact of Adventure on a Heathkit kit computer to Adventureland on the mass-market TRS-80, it does seem a little picayune to rob Scott Adams of the credit. I think I’ll hedge my bets with the qualifier “mass-market.” Thanks!

Jason Dyer

October 20, 2023 at 7:38 pm

It had a big impact, but in a lateral way — the developer for the Heathkit Adventure port (Gordon Letwin) went on to do the Microsoft Adventure port which is one of the few that became fairly widespread in home computers (roughly analogous to Level 9’s version in Europe). Letwin is now one of the Microsoft billionaires.

Based on the description, the first exhibition of the game in public seems to have been multiplayer? Although I’m still wondering if that was just being described badly, and that didn’t pass on to any publicly available ports.

I think how you have the sentence phrased now is perfect.

Mateus Fedozzi

October 6, 2023 at 6:36 pm

Time. Controlling it has always been a staple on Mechner’s art. One had also to master time in order to save the Persian princess, years before one got aboard the Orient Express. I first met this princess when I was a kid. That made me a Mechner fan for life. Then came Prince 2 and Last Express, but I could only afford a copy of the train adventure after I beat Sands of Time. It had become a rare and expensive game by the 2000s. But when I finally put my hands on it, man! It was oh so much better than I could have imagined! Good for Mechner’s reputation in my mind that by then I was a hardcore gamer and Last Express wouldn’t scare the heck away from me, because it indeed is a frightening game to those who are taking a first glance at it. Besides, not only the gameplay didn’t scare me, but I was also old enough to appreciate the artistic side of it. A broken masterpiece that every serious gamer or history buff should try.

Prerok

October 6, 2023 at 7:53 pm

Nit: “to spent” -> “to spend”

Thank you for another great article!

Jimmy Maher

October 6, 2023 at 8:27 pm

Thanks!

Zed Banville

October 6, 2023 at 8:09 pm

“if General Lee had not ordered a frontal assault on Seminary Ridge at the Battle of Gettysburg”

General Lee didn’t order a frontal assault on Seminary Ridge, which was occupied by Confederate troops on the first of Gettysburg’s three days, fought north and northwest of the town between elements of the Confederate and Union forces, the latter of which then fell back on Cemetery Ridge to the south of the town (also Cemetery Hill, Culp’s Hill, and belatedly Little Round Top and Round Top).

Jimmy Maher

October 6, 2023 at 8:29 pm

And it even reads better when simplified. ;) Thanks!

Krsto

October 6, 2023 at 8:56 pm

Another great article Jimmy and fair criticism of the game mechanics.

As for The Last Express, for me it is great game with some flaws, it’s attention to detail probably not surpassed in a genre to this day, too bad it’s flopped, I’m really interested in what kind of follow-up games Mechner had in mind if that one was succesful.

Artistic decision to go for comic book style rotoscoped characters can never be commended enough, it really suited intended atmosphere of the game, and also helped game to graphically age pretty well, especially in comparison with FMV or 3d modeled characters of that period.

Not that I am some kind of a expert, but for me TLE feels too European for American market, and probably not high profile enough for the European market of that time to be succesful.

Busca

October 7, 2023 at 8:08 am

Two more quotes by Mechner from the interview linked below on aspects you mention here:

“I think I’ve always loved historical fiction that’s set against a believable background. Alexandre Dumas is the great master. Reading for example The Three Musketeers or Queen Margot, they’re invented stories about made-up characters, but the fact that D’Artagnan and the Three Musketeers are so believable and their adventures are so classic, I think it’s because they’re set against a background that’s been really meticulously researched.”

“[T]he idea that by rotoscoping filmed footage we could make it resemble a kind of a hand-drawn pen and ink drawing reminiscent of the Art Nouveau, the Toulouse-Lautrec style in drawings of the time, that just appealed to us”.

Jazerus

October 6, 2023 at 9:10 pm

There’s something philosophical about this game being a dying last gasp of the FMV adventure genre portraying a setting that is the dying last gasp of a historical era. Two lost worlds meeting to tell one last story…

The Wargaming Scribe

October 6, 2023 at 10:20 pm

Great article really. I never played The Last Express and only knew it by name ; it is on my short-term playlist.

Regarding your comment about games playing, (“Yet there was a big drawback to this approach: the game could and usually did run away from you. If you didn’t happen to be in the right place at the right time to answer the telephone or to intercept the postman, you were just out of luck; the crime was doomed to go unsolved.”) I would like to mention an independent game that managed to solve this design/gameplay “problem” perfectly : Elsinore

In Elsinore, you play Ophelia from Hamlet and must basically save everyone from the play including yourself, with the play “resetting” to its beginning every time you die or (should you survive) when the play ends, except Ophelia remembers everything that happened and can now use the new pieces of information, Groundhog Day style. It works particularly well because most players probably know the general story of Hamlet, so they can jump into the plot right away (no need to “learn” the motivations of the various characters), and of course it is pretty fun to fool around and for instance follow Rosencrantz and Guildenstern the whole play rather than be where Ophelia is supposed to be.

I love Elsinore even though I am not the Adventure Scribe, and given the kind of game you cover I suspect you would love it.

Jimmy Maher

October 7, 2023 at 8:56 am

That does sound interesting. My wife always says that I treat my Complete Works of Shakespeare like religious folks do their Bibles…

Zed Banville

October 14, 2023 at 4:52 am

If only Rosencrantz and Guildenstern had been able to remember what happened previously whenever they were reset. Or is it Guildenstern and Rosencrantz?

Sion Fiction

March 15, 2024 at 10:48 am

A Hamlet Time Loop Point ‘n’ Clicker?!

Why have I never heard of this?

Ola Hansson

October 7, 2023 at 1:48 am

I had wished to play it since I read Richard Rouse’s book in 2002, but I didn’t play The Last Express until 2015 and it quickly became my all-time favourite game.

I am firmly in the clock time corner and very glad Mechner didn’t go for plot time. To me, the immersive aspect of being just one of the passengers aboard is its greatest appeal and worthy of much more praise than the story.

Not that the story is bad, but to my jaded comic book-reading eyes, it seems like an overenthusiastic and slightly immature pastiche of Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese. It wouldn’t surprise me if Mechner happened to come across Corto Maltese while in Paris and that it exerted considerable influence on the game.

It might be that European comic book feel that explains some of the misalignment with the American audience, which is brought up in a very different comic book culture of super heroes and science fiction?

Busca

October 7, 2023 at 7:45 am

Right in one on Corto Maltese. In the Stay Forever interview I’ve linked below, Mechner recounts how in Paris he “really fell in love with French graphic novels” and goes on to say:

“So the history, living in Europe was an influence, reading graphic novels like Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese, François Schuiten, all of these inspirations as well as the old Hollywood movies like The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, The Third Man – which Tomi and I both loved – all fed into it”.

Jimmy Maher

October 7, 2023 at 8:58 am

Broken Sword had a lot of the same inspirations, and unsurprisingly looks quite similar — another connection I tried to work into the article but just couldn’t manage to do elegantly.

ZUrlocker

October 7, 2023 at 1:56 am

Great write up, Jimmy. I am a huge fan of Mechner’s work and his meta-work (e.g. The Making of Prince of Persia journals.) I remember when The Last Express came out. I was busy with work as a product manager in a software company and by the time my project was complete The Last Express had faded already. I think the ambition and the thoughtfulness that went into the game is astounding. The rotoscoping, the soundtrack, the voice acting and the story all are very solid. But, the limited size of the actual screen area and the slow 1 frame per second animation works makes the user experience very clunky indeed. It would be amazing to see this game with a slightly different user interface, perhaps smoother animation and better keyboard/mouse handling. Mechner has written a fair amount about this game, but I think it deserves it’s own proper full development diary with design docs.

Jimmy Maher

October 7, 2023 at 6:47 am

He’s in the process of doing so, publishing his journal entries on his website with a time delay of exactly 30 years. I used some of the early entries here, but we’ll have to wait another four years to have the full story in his own contemporaneous words.

Sion Fiction

March 15, 2024 at 11:08 am

Jordans autobiographical graphic novel Memoir thing “Replay,

Memoir of an uprooted family” is out on 19 March 2024″ & covers the making of The Last Express.

https://www.jordanmechner.com/en/books/replay/

It looks really good actually, & in typical Jordan Mechner fashion he wrote, penciled, inked, printed & stitched every page by hand.

I think most of these Auteur Overachievers are either highly overrated [Chris Nolan], got very lucky [Zack Snyder] or are just plain old grifters [Michael Bay]. But Jordan seems to be the real deal – he oozes talent.

Busca

October 7, 2023 at 7:36 am

Very interesting story about a game I’d read a bit about, but which I’ve not yet played. And another landmark for the discussion you include about ‘real time’ vs ‘plot time’ and alternative and hybrid solutions.

Jimmy, I don’t see it mentioned in your sources, so in case you haven’t yet heard or read it (and for any other readers interested), there is a 2019 interview (in English, audio and transcript) with Jordan Mechner about TLE by the German retro gaming podcast Stay Forever as a follow-up to their coverage of the game (contains a few limited bits which might be considered potential spoilers).

Some of it reflects aspects you’ve written about here, but there are also additional parts I found interesting, e.g. on his inspirations, the creation process (inter alia comparing it to a runaway train itself) and financing, technical bits etc. – I learned even Miyazaki animes were a motivation in one regard and didn’t know years later he worked with Paul Verhoeven on a script for a film based on the game. A good complement to your article, in my book, for those whose appetite you’ve whetted with it.

Ozzy

October 7, 2023 at 4:02 pm

Did Jordan Mechner ever mention Cruise for a Corpse as a reference ?

The game was developed in 1991 by Delphine Software. As he was apparently connected with France around that time it could be that he has at least noticed that game.

Vince

October 8, 2023 at 1:23 pm

I think Cruise for a Corpse is an very worthwhile reference since it uses both rotoscoped animations as pure adventure and it is set in a cruise ship with a small cast of characters, with the passing of time as a main game mechanic.

It is an interesting counterpoint as it’s the best example I can think of that shows how Ballyhoo’s (or Colonel’s Bequest/Gabriel Knight) implementation of plot-advanced-time can go horribly wrong.

Cruise for a Corpse is incredibly specific about which action you need to accomplish at a determinate time slot to trigger the clock to advance, to a degree that it effectively forces you to visit almost every location and speak to every character (each of which has dozens of lines of dialogue by the end) at every turn of the clock, making it seem incredibly arbitrary and making it feel like tedious busywork, rather than engendering the feeling of being a detective solving a mystery.

The Last Express has its flaws, but even purely in terms of mechanics is a far superior game.

Ian Brett Cooper

October 7, 2023 at 12:02 pm

The idea that The Last Express was a flawed experiment is complete nonsense. This game failed purely because Broderbund dropped the ball by failing to market it. It remains the most played game in my collection for a reason – it is a classic, and one of the best games ever made.

Feldspar

October 7, 2023 at 1:14 pm

As someone who owned this game in the late 90s, I tried to pick it up several times but always had the same experience. While it has very laudable ambitions, and starts on a very strong foot I feel like unless I knew to be in the right place and the right time, at some point I ended up wandering back and forth on the empty train with nothing happening and no idea what I was supposed to do to move forward in the story and just sort of got bored and quit. This was my experience anyway but I suspect a lot of players had the same experience, similar to how you described Infocom’s Deadline I think. You did kind of touch on it a few times in the article and especially saying that it’s not really a “casual” game unlike a lot of narrative-heavy games recently where it’s easy to advance the story. I had played a bunch of adventure games of the period like Myst and similar games but playing this game really needed to be a completely different mindset and I guess one I was never prepared to figure out.

At some point I did watch a YouTube edit of all the cutscenes as a “movie” and found it to be a pretty engaging experience on a par with a well made movie. Even though of course I know just watching an edit defeats the interactivity unique to making a game.

Maybe I should pick it up again and try more systematically to figure out everything going on aboard the train and what events you need to witness when in order to advance the story.

On a really low brow note, I guess the “be in the right place at the right time to witness the right events” type of gameplay, funny enough did recently have a pretty big breakout commercial success with the Five Nights at Freddy’s series and its imitators among younger kids; being a game that copies its gameplay from the infamous FMV game Night Trap where the player can watch a live security camera feed of only one room at a time in a building and has to track the movements of some creepy monsters in real time in order to thwart them. Though I suspect the success of the games doesn’t have much to do with the gameplay but just its association with the cottage industry of YouTubers who pretend to act scared while playing horror games. It was a big enough deal to get its own feature film anyway.

Gordon Cameron

October 7, 2023 at 5:44 pm

“Only then could you make your winning run, where everything just kind of worked out for you in the way it always seems to for Hercule Poirot on the very first try.”

This popped out to me as a very happy turn of phrase.

I’ve had Last Express for a while now but didn’t put much time into it. Realizing the effort that went into making it does pique my interest somewhat.

Andy

October 7, 2023 at 10:02 pm

Count me as someone for whom this was very much a success. Admittedly I haven’t replayed it recently… but in my memory from 20 years ago, the sense of immersion in this game was absolutely unmatched, and the quality of that aspect of the experience entirely justified all the structural choices that served it.

The objections raised here — that making the player replay parts of the timeline to get past roadblocks is just typical “punishment,” and that the interlocking choreography of all the characters is interesting in theory but not really worth much to a player(!) — to me seem weirdly resistant to the special experience the game offers. This game really gave me the opportunity and the encouragement to make believe I was there, in a way no other adventure game did. I eagerly took it up on that!

Sure, Deadline-style trial-and-error replay is “artificial” and immersion-breaking, but I daresay so is pretty much all adventure gamery, wherein making progress usually involves asking “what have I seen that seems likeliest to lead to progress in a game?” That’s not immersion!

Whereas The Last Express was one of the very few game experiences I’ve ever had where I genuinely found myself feeling that the question at hand was “what shall I do in this place where I find myself, and in response to these people I’m encountering” rather than “what are you supposed to do in this game.” That was a wonderful feeling, and a huge achievement.

And sure — I can recall that there were parts of the game where that didn’t entirely hold true, and some standard game-think did inevitably creep in. But… so what? What else is new? To call the game a failed experiment that revealed the “limits of fun,” just because it had some elements that did, in fact, resemble other games, seems backward. The experimental aspects were… everything else!

Personally, my main reservation about the game was, as someone else here mentions, the fantastical element, which is only introduced late in the game and feels like a betrayal of genre. Either it was a miscalculation to include that in the plot, or it was a miscalculation not to better prepare the player from early on. Indiana Jones generally doesn’t encounter anything supernatural until the very end of his adventures, but the tone of the storytelling makes clear from the beginning that it’s in the realm of possibility. Whereas the Agatha Christie / Lady Vanishes points of reference here suggest the opposite. Oh well.

Derek

October 8, 2023 at 3:51 am

My opinions are similar to yours. I’ve only played through it once; reading about how much research went into its creation makes me want to play again.

Leo Vellès

October 7, 2023 at 10:53 pm

This is, for me, the saddest flop in video game history

Jordan Mechner

October 8, 2023 at 6:36 am

I enjoyed this article and am sure other former Smoking Car team members will, too. Great job! A few minor details maybe worth correcting:

Tomi didn’t work for Broderbund, she was a free agent (other than a short stint running Broderbund’s French office circa 1990). She co-founded Sensei Software circa 1984, whose educational products were published by Broderbund as an affiliated label.

It wasn’t Tomi but Patrick Ladislav with me in the Athens train yard and other early European research. The details of who did what when are (somewhat) clarified by my 1993 journals, available at https://www.jordanmechner.com/en/library/1993-journals/ (an ongoing feature on my website, with a new batch of entries added every Wednesday).

Myst was developed by the Miller brothers at Cyan as an outside product; it wasn’t part of any Broderbund plan. At that time, Broderbund’s focus and direction was towards educational and productivity software, moving away from the games business. They certainly had no expectation Myst was going to become a hit in 1993. Its massive success took them by surprise. Once it became a breakout smash, they quickly reconfigured to ride that horse for all it was worth.

Highly unlikely that Last Express ever had a $1M marketing budget. Not sure where that number came from, but it sounds like it might be an estimate of Broderbund’s total investment in The Last Express, including royalty advances and their contribution to production costs. The launch marketing campaign was almost nonexistent, for various reasons, including personnel changes and restructuring around Broderbund’s merger with The Learning Company. A big factor was that Last Express had already blown its schedule twice. From Broderbund’s point of view, missing Christmas 1996 was the final straw. By the time the game was ready to ship in April 1997, people who had believed in and backed the product internally were no longer with the company. Last Express didn’t fit with the current strategy; Broderbund did not expect it to sell well. For understandable reasons, they’d essentially written it off and moved on. There’s a longer story to be told there and your article already has a very ambitious scope, but I think that point is worth clarifying.

The Newsweek article and other PR around Last Express release was the result of guerrilla marketing by Smoking Car and friends, not Broderbund. Tomi did more than just write the article, she pitched it to Newsweek in the first place.

Thanks for writing this article! I’m impressed by the amount of information you were able to assimilate from existing sources, and very glad that Last Express continues to live on. For those interested, here’s a link to my own Last Express page. Along with the weekly addition to the 30-years-ago journal, I occasionally add new commentary or behind-the-scenes materials from the archives: https://www.jordanmechner.com/en/games-movies/the-last-express/

Jimmy Maher

October 8, 2023 at 7:36 am

Thanks for commenting, Jordan, and thanks for the game! I’ll have another look at the parts of the article you mention. (In particular, the paragraph on Doug Carlston and Myst was indeed too speculative and generally ill-advised.)

That said:

The $1 million marketing figure actually comes from your own emails to and from Broderbund, which are included in the archive you donated to the Strong Museum of Play. Your email dated July 7, 1997 — the same one quoted from at some length in the article — has a section headline of “Why consumer awareness is low despite a $1 million launch.” It goes on to elaborate on “a large sell-in backed by an estimated $1 million in marketing support…”

As I noted in the article proper, I’m also a little confused by this idea that Broderbund’s merger with The Learning Company was somehow a factor in The Last Express’s failure. The Last Express was finished in February of 1997; the merger you mention occurred in June of 1998, long after the game had been left for dead.

Josh T.

October 8, 2023 at 2:06 pm

I don’t know if there’s a timeline of the acquisition online somewhere (Wikipedia doesn’t seem to mention it), but it’s possible that the merger was in the works for a couple of years and Broderbund was adjusting its finances in 1996/7 accordingly. At least with the Disney/Fox and Microsoft/Activision acquisitions (which are admittedly much, much larger in scope) those took at least 18 months to come to fruition.

A quick Google search online shows that there was apparently a merger planned before SoftKey’s takeover of TLC: https://money.cnn.com/1998/06/22/deals/broderbund/ I am sure you will get to this merger in a later article, so maybe you can find a more concrete timeline of how this deal came about.

Brent

October 8, 2023 at 11:15 pm

Loved seeing the interviews with your dad in The Making of Karateka. If you haven’t already you should check out this unique digital museum, Jimmy!

Jordan Mechner

October 9, 2023 at 9:44 am