If someone were to ask you at the beginning of 1998 which studio was most likely to release a little-sung adventure game that year that would go on to become a well-loved cult classic, you probably wouldn’t think of the little Pennsylvania outfit known as DreamForge Intertainment. For DreamForge’s track record with the adventure genre — or with any other genre, for that matter — was the opposite of imposing.

The studio was founded in 1990 under the name of Event Horizon Software. The people behind it were Jim Namestka, Tom Holmes, and Chris Straka, a trio of programmers recently employed by Paragon Software, a company best known for Marvel Superheroes action games and for conceptually ambitious but functionally half-baked CRPGs, most of which were based on the tabletop properties of Game Designers’ Workshop. After leaving Paragon in a huff over what they described as profound disagreements with the “creative direction” being taken there, Namestka, Holmes, and Straka proceeded to specialize in… yet more conceptually ambitious but functionally half-baked CRPGs, at first without the benefit of a license. In 1993, they remedied the latter problem at least by signing on with SSI to make Dungeons & Dragons computer games. The same year, they changed the name of their company. “We used the word ‘dream’ because that’s what we make, ‘forge’ because it implies craftsmanship, and ‘Intertainment’ with an ‘I’ because it represents the next big thing — interactive entertainment,” said Namestka just after the switch. More important than all that, however, the name change avoided confusion with a pornography purveyor that was also called Event Horizon.

DreamForge’s first Dungeons & Dragons game is their best remembered today (not that this is a particularly high bar to meet). Three years before Diablo, Dungeon Hack tried to deliver an infinitely replayable hack-and-slash CRPG through the magic of procedurally generated dungeons that were new each time out. While it cannot be compared to the dangerously addictive Diablo in any sense but its core concept, some found it a lot of fun at the time.

In these latter days of the Dungeons & Dragons license, SSI’s focus had shifted from quality to quantity. DreamForge was, for better or for worse, a good fit for that ethic. Thus they followed up Dungeon Hack with three more Dungeons & Dragons action-RPGs in remarkably short order. As a 1994 profile in Computer Gaming World magazine put it, DreamForge saw their principal competitive advantage as the way “they managed to put out products in a six-month development cycle rather than the more leisurely pace [of] other software houses.” They certainly weren’t a studio known for innovation, but, if you just needed a serviceable game that worked off of an established template, and especially if you needed it delivered quickly, they could do that for you as well as just about anyone.

After the Dungeons & Dragons license was gone for good, DreamForge continued in this mode for SSI and other publishers, making games like War Wind I and II, some of the very first clones of Blizzard Entertainment’s ultra-successful Warcraft II to hit the market. DreamForge was happy to jump on just about any trend. For example, the same year that they made Sanitarium, their aforementioned cult-classic adventure game that will be our main subject for today, they made TNN Outdoors Pro Hunter, which was inspired by Deer Hunter, the schlockiest game ever to sell millions of copies.

Sanitarium, however, was different enough to stand out like the proverbial sore thumb in a catalog chock full of workmanlike games made for hire. The only other DreamForge game other than it that might be credibly described as a passion project rather than a business contract fulfilled is, perhaps not coincidentally, also the studio’s only other point-and-click adventure game. Here I speak of 1996’s Chronomaster, a noble effort in its way that sadly turned out a bit of a mess.

Chronomaster’s creative pedigree was undeniably impressive: its audacious central conceit, involving private pocket universes owed by the rich tech-bros of the far future, was just about the last idea ever dreamed up by the science-fiction author Roger Zelazny before his premature death from cancer. Once Zelazny’s illness had made it impossible for him to continue, the script was finished off by his romantic partner and fellow writer Jane Lindskold. Unfortunately, though, DreamForge didn’t bother to sweat the details on their end. The game’s interface is unbelievably convoluted, requiring you to rummage through a menu just to move your character from one point to another on the screen. And the game design is even worse than the interface, being littered with nonsensical puzzles, unclued sudden deaths, and hidden dead ends — not to mention one of the most irritating mazes ever to appear in a graphic adventure. The protagonist mutters, “Swell! A maze!” and then sighs theatrically when you encounter it. DreamForge clearly knew that this would be the player’s reaction as well. So… why include it???? The mind boggles…

Passion project or not, nothing about Chronomaster lent much hope for DreamForge’s return to the adventure genre with Sanitarium. Which is precisely why the latter game is such a pleasant surprise.

Sanitarium was, one senses, an indulgence, a reward granted by the small studio’s founders to their hard-working employees, who had for more than half a decade been cranking out a steady two games per year — games that might not have been masterpieces, but neither were they, with the arguable exception of Chronomaster, disasters. For once, the folks on the front lines at DreamForge were given a chance to let their imaginations run wild over a blank canvas. Within reason, that is: DreamForge was not a wealthy studio, so the game would have to be finished on a fairly tight budget, within a fairly short amount of time. Cognizant of this, the employees envisioned a very traditionalist point-and-clicker.

A measure of constraint is by no means always a bad thing. In this case, it caused DreamForge to steer clear of the trend toward “interactive movies” featuring digitized video clips of real actors. The mixture of pixel art and pre-rendered 3D that they relied upon instead may have seemed dismayingly old-fashioned to some at the time, but today we can say that Sanitarium’s visuals have aged far better than many a more expensive production of the era. Rather than anything released more recently, LucasArts’s five-year-old Day of the Tentacle became DreamForge’s model in terms of technology and puzzle design. Definitely not in terms of mood, though: Tentacle was a cartoon comedy, which has always been the low-hanging fruit of the genre, for all that LucasArts was masterful at executing it. Sanitarium‘s atmosphere was to be dark and grim, a braver thing to attempt and a trickier one to pull off. The game was to combine classic and contemporary psychological horror, having a list of inspirations that included The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits, Jacob’s Ladder, Se7en, and 12 Monkeys.

The core gang of four that coalesced around the game consisted of design lead Mike Nicholson, writer Chris Pasetto, head programmer Chad Freeman, and art director Eric Rice. The team was unusual in that, although almost every single one of its members would enjoy a long later career in mainstream commercial game development, none would ever make another adventure game.

Luckily for us, DreamForge made their second and last time at bat with the genre count. Every problem Chronomaster had has been fixed in Sanitarium. The interface is clean and simple: right click and hold to walk around the screen, right click over your avatar to bring up a radial menu of the objects he’s carrying, left click to interact with things out in the environment. Then, too, DreamForge embraced LucasArts’s “no deaths and no dead ends” philosophy of design. To this they married a wide variety of puzzles that are not too hard but not too easy either, being balanced nicely to keep you engaged without ever stopping your progress through the plot for too long. If there was an award for most improved maker of adventure games, DreamForge would surely deserve the prize for 1998 on the basis of Sanitarium’s surface qualities alone.

Having said that, though, I also have to tell you that its surface qualities are not the reason Sanitarium is a game that sticks with you long after you’ve finished it. It’s the story and the themes that are really special. As a critic, I hate to use this word, but sometimes it’s unavoidable: this game has soul.

Mind you, this quality of soulfulness is not exactly front and center from the beginning. Your first glance at the blood and guts that are strewn across its environments may make you think of a hundred other 1990s videogames which love ultra-violence for its own sake. The story too initially seems decidedly unpromising. It does, after all, revolve around amnesia, that most clichéd of all the tools in a fiction writer’s toolbox.

You play a fellow known only as Max, whom an apparent car accident has recently left in a coma. Instead of a hospital bed, you awaken from your long sleep in the titular sanitarium, a place straight out of a Victorian penny dreadful. Nothing around or on your person is of much help in remembering who you are: you’re wearing only a set of anonymous nurse’s scrubs, and your whole head is so swaddled in bandages that you can’t even see what you look like. Your objective in the game is, naturally, to figure out who you are, how you arrived in this horrible place, and how you can escape your predicament. You pass through a series of dream sequences, over the course of which you slowly begin to piece these things together. (This vignette structure is one of the ways the game keeps a lid on its difficulty, by ensuring that the combinatorial explosion of available puzzles and objects never gets out of hand.) And a surprising thing happens as you venture deeper into the game: what started out as just another exercise in B-movie-style horror and surrealism slowly reveals itself to have much more on its mind and its heart than first appeared to be the case. It addresses some very sensitive topics — among them child abuse and the death of a child — with more empathy and compassion than I would ever have dared to expect.

Sanitarium does walk a fine line at times between the overwrought and the profound; even when I was halfway through the game, I still wasn’t entirely sure which side of that line it would ultimately land on. When all is said and done, though, it dodges the worst of the traps it’s laid for itself by sticking the ending in a way that games like this too seldom do. Sanitarium, you see, goes against the surrealistic tide by pretty thoroughly explaining all of its weirdness. “I felt very strongly that, having invested so much in the characters, an unresolved ending would feel extremely cheap to the player,” says Mike Nicholson. You are absolutely correct, Mike; kudos to you for staying the course and delivering an interactive story that’s fully realized in the Aristotelian sense. The player does get to find out what is really going on, and even gets to enjoy a happy ending.

So, my advice to you, my good readers, is to trust the game even when it seems dubiously worthy of your trust, to give it a chance to reveal its real self at its own speed. If you do so, I think you’ll find that it repays your patience and willingness to withhold judgment handsomely.

At first, Sanitarium can seem like it just wants to be gruesome, in an all too typical videogame sort of way. But first impressions can be deceiving…

The game dwells on the theme of childhood innocence endangered as obsessively as Holden Caulfield. Even your selections from the utility menus — save and load, etc. — are repeated by a creepy, disembodied chorus of children’s voices.

This is neither the first nor the last adventure game to feature a macabre circus. Here, however, its shock value is shot through with real sadness, as Max takes on the persona of the childhood sister whom he lost. At moments like these, the game transcends its grindcore surface qualities.

This cut scene, in which Max remembers his failure to fulfill his dying sister’s last wish, cuts to the bone with a rusty blade of truth.

Ancient Aztecs are hardly strangers to adventure games. Again, though, this game is weirdly good at transcending its many clichés — beginning, of course, with the amnesiac protagonist.

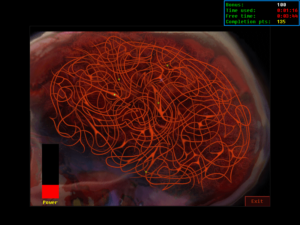

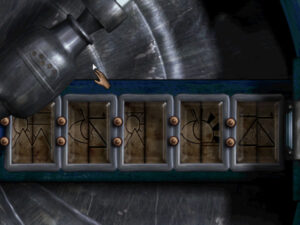

The puzzles are numerous and varied: inventory puzzles, conversation puzzles, a few action-oriented tests of timing, plus some set-piece Myst-style puzzles like this one.

Screenshots like the one above show that DreamForge’s budget and time were not unlimited. This is supposed to be an isometric view, but the “camera” angle is too extreme, so that it ends up looking like a cutaway view of the floors of the house. Adventure gamers would have to learn to forgive such little infelicities if the genre was to stay alive at all. It’s not too big a thing to ask, in my opinion.

Sanitarium is by no means a AAA game. It was made in just sixteen months, on a sharply limited budget. “We worked with the time and budget we had,” says Mike Nicholson. Fair enough; no one can ask for more. That said, its creators’ limited resources do show through: the game’s graphics are far from the state of the art even for 1998, its voice acting marked by a limited number of actors and by the inherent limitations of some of them — including the one playing Max himself, whose histrionics are sometimes more than a little bit over the top. Yet, even when setting aside its unusually weighty thematic ambitions, Sanitarium remains a well-crafted, even well-polished game within the set of restrictions that are its lot in life. If it does nothing really new, it does the tried and true very, very well. In that sense, it offered hope back in 1998 for a genre that was increasingly in need of it.

There’s a standard narrative about the history of adventure gaming, which you can read of here and there on this site as well as plenty of other places. It describes how adventures rose to become arguably the hottest of all gaming genres during the first half of the 1990s. And then, with dizzying abruptness, the genre “died,” for a whole range of reasons that different chroniclers choose to emphasize to differing degrees: too many games in general, and especially too many with a poor grasp on the fundamentals of good adventure design; a lack of innovative new design ideas; the terrible economics of paying $50 or more for a game that you would be done with after just five to ten hours; an inability to compete with the fast-paced, visceral nature of the latest first-person shooters and real-time strategies; the challenges of distribution in a marketplace where the number of games was growing far faster than the available shelf space at retail, even as online digital distribution was not yet practical for asset-heavy games like these.

All of these reasons are valid when considered in their appropriate context. Nevertheless, the standard narrative masks an important fact. Although adventure games definitely went into a pronounced commercial decline after 1995, definitely became niche rather than mainstream products in gaming’s new world order, they never actually “died” at all. Even in the very worst years for the genre, new adventures were still released. And in the due course of time, the adventure game learned to reckon with its relegation to niche status, found ways to survive and even to be modestly profitable as part of a long tail of games that trucked along behind the razzle-dazzle of Quake, Unreal, and Starcraft.

Adventures’ means of living on after their alleged death were varied. Most obviously, they entailed reduced budgets, even though that meant accepting reduced production values, and reduced price points, even though that cut into an already precarious bottom line. More and more in the course of time, they would include moving production out of North America and Western Europe to Asia and Eastern Europe, where artists and programmers were willing and able to work much more cheaply. This new breed of adventure game would not be advertised in the front pages of glossy magazines and featured in flashy end-cap displays inside stores, as their predecessors had been. These adventure games were thrilled if they could just secure a bottom shelf somewhere for themselves; when they couldn’t, there were always the mail-order and Internet-based storefronts, who, unlike the brick-and-mortar retailers, were in a position to stock any and every game in their warehouses, no matter how niche its appeal.

As a game produced on a modest budget, with correspondingly modest commercial expectations on the part of its developer, Sanitarium can be seen as an early example of these trends, coming along even as the last of the bigger-budget adventure games from the big studios — titles like Black Dahlia, The X-Files Game, Grim Fandango, and Gabriel Knight 3 — were still either in the pipeline or fresh on store shelves.

And Sanitarium serves as an early riposte to a lot of the assumptions behind the standard histories of adventure games in yet one more way. I, for one, am not at all convinced that the genre’s decline in prominence actually led to worse games. When adventures were no longer flagship titles on which the stock prices of their corporate parents depended, there was less pressure to release them before their time. When the people making them were doing so strictly out of love for the genre instead of because they were chasing the trendy flavor of the month, said people were more willing to sweat the details of design. Likewise, when the budget couldn’t be stretched enough to create an audiovisual spectacle, the only way to stand out was through excellent writing and puzzles. And when the old “Siliwood” vision of adventure games as interactive movies populated by real actors was thrown onto the dustbin of history, studios were able to return to older approaches that were often more satisfying than watching reams of grainy green-screened video. So, not only did a year never go by without producing at least a few new adventures, but at least one or two of those adventures were always pretty darn good, just like Sanitarium is. Not bad for a dead genre.

The obvious comparison to make is with the graphic adventure’s evolutionary forefather, the text adventure, which went through a similar boom and bust about a decade before its progeny. By the early 1990s, the text adventure really was dead as a commercial proposition, deader than the graphic adventure would ever be. And yet the text adventure writ large did not die. Its disappearance from store shelves rather left the field open to impassioned amateurs, who programmed tools for making them that were more sophisticated than anything any of the commercial houses could ever lay claim to. Then, being freed by the absence of economic pressure to focus on design, writing, and innovation, the amateurs used these tools to create games that were not just as good as but in many ways better than the best of the 1980s. The major difference in the case of graphic adventures was that the latter were able to maintain a low-key commercial presence, even as open-source authoring systems like Adventure Game Studio would eventually allow amateurs to create remarkably sophisticated games of this style as well. The beginning of that scene is still a few years removed from the point at which we now stand in these histories, but I do look forward to covering it alongside the professional graphic adventures — and the amateur text adventures, of course — in the future.

In the meantime, though, there is Sanitarium, the advance guard that pointed the way to where the genre as a whole would have to go within the next couple of years. To have a future, adventure games would have to reconnect with their past, pretending the Siliwood craze had never happened and refocusing on the fundamentals. This is exactly what Sanitarium does, to fine effect.

The rest of the story of Sanitarium and DreamForge Intertainment is far briefer than that of the adventure game in general. Instead of DreamForge’s usual partner SSI, Sanitarium was published by the relatively brief-lived American Softworks Corporation, something of a dumping ground for second-tier games like this one that didn’t much interest the glitzier publishers. Needless to say, Sanitarium wasn’t a big seller.[1]Gazing back through the rose-tinted glasses of memory, Mike Nicholson guesses that Sanitarium sold around 300,000 copies. Based on my knowledge of the industry and the game’s public profile, I suspect that this figure is inflated by a factor of two to five. If it were correct, Sanitarium would stand as the best-selling game DreamForge ever made by a huge margin, raising the question of why they didn’t immediately invest in another adventure. For all that much of the form and spirit of the post-millennial adventure game can be seen here in a nascent form, it would take cleverer publishers than ASC to figure out how to sell the games consistently at a (modest) profit — another story for another time.

As it was, this weirdly aberrant game in the DreamForge catalog justified that description by becoming the last of its kind from them. In fact, the studio finished only one more game of any type after Sanitarium and TNN Outdoors Pro Hunter, their odd couple of 1998: that game being the more typically workmanlike Warhammer 40,000: Rites of War of 1999. With DreamForge’s traditional business model of making derivative games that were just good enough becoming harder and harder to sustain in the changing industry, the company was dissolved not long after.

Sanitarium stands today as their one real moment of glory, their one game that truly deserves to be discovered and appreciated by a new generation of gamers. Thankfully, its presence on modern digital storefronts allows this. Personally, I rank it alongside Journeyman Project 3 and Tex Murphy: Overseer as one of my three favorite graphic adventures of 1998. While the former two titles both represent the end of an era of adventure gaming, Sanitarium is the dawning glow of a new one. I submit it to you as Exhibit Number One for my case that the adventure game’s life after death will be in its own way every bit as exciting as its lusty youth.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: Computer Gaming World of January 1994, April 1996, and September 1998; Retro Gamer 132. Plus the SSI archive at the Strong Museum of Play.

Where to Get It: Sanitarium is available for digital purchase at GOG.com.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Gazing back through the rose-tinted glasses of memory, Mike Nicholson guesses that Sanitarium sold around 300,000 copies. Based on my knowledge of the industry and the game’s public profile, I suspect that this figure is inflated by a factor of two to five. If it were correct, Sanitarium would stand as the best-selling game DreamForge ever made by a huge margin, raising the question of why they didn’t immediately invest in another adventure. |

|---|