Given that Hitchhiker’s is both one of the most commercially successful text adventures ever released and one that oozes with interesting things to talk about, I thought I would look at the experience in more detail than I have any Infocom game in quite some time. As we’ll see, Hitchhiker’s is not least interesting in that it manages to represent both a step forward and a step back for Infocom and the art of interactive fiction. What follows is a sort of guided tour of the game.

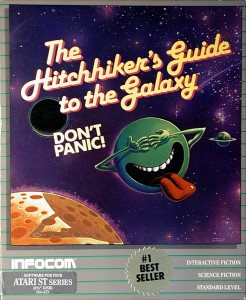

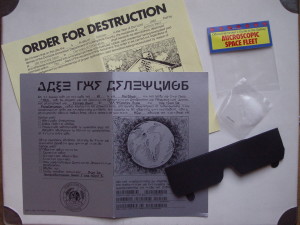

As with any Infocom game, the experience of Hitchhiker’s for any original player began long before she put the disk in the drive. It began with the box and its contents. The Hitchhiker’s package is one of the most storied of all from this company that became so famous for their rich packages. It’s bursting with stuff, most of it irrelevant to the actual contents of the disk but all of it fun: an advertising brochure for the titular guidebook;[1]“As seen on Tri-D!” a microscopic space fleet;[2]Easily mistaken for an empty plastic baggie. a set of “peril-sensitive sunglasses”;[3]They turn opaque when danger is at hand to avoid upsetting your delicate sensibilities. The ones in the game package are, naturally, made of black construction paper. a piece of pocket fluff; a set of destruct orders for Arthur Dent’s house and the Earth; the obligatory “Don’t Panic!” button.[4]These were manufactured in huge quantities and given away for some time at trade shows and the like as well as being inserted into game boxes.

Impressive as the packaging is, not all of it was to Douglas Adams’s taste. He hated the gibbering green planet,[5]Or whatever it’s supposed to be. which had been designed and pressed into service by Simon & Schuster’s Pocket Books imprint without any input from him when they first began to publish the books in North America. He briefly kicked up a fuss when he saw it leering at him from the Infocom box as well, but Infocom’s contacts at Simon & Schuster, whom Infocom was considering allowing to buy them at just this time and thus preferred to remain on good terms with, had asked with some urgency that it be there. By the time Adams saw the box there wasn’t really time to change it anyway. And so the planet — and I have to agree with him that it’s pretty hideous — remained.

The game proper begins just where the books and the smorgasbord of other variations of Hitchhiker’s did: with you as Arthur Dent waking up hungover in bed on what is going to be “the worst day of your life.” You immediately get a couple of clues that this is not going to be your typical Infocom game. The first command you must enter is “TURN ON LIGHT,” a typical enough action to take upon waking up in a dark bedroom, perhaps, but one that could momentarily stump a seasoned adventurer, so accustomed to living in an object-oriented world where she can only interact with what the game tells her exists around her; the game, you see, never mentions the presence of a light switch or a light. Hitchhiker’s will continue to occasionally accept or demand inputs that you, the Seasoned Adventurer, just don’t expect to work. And then when you dutifully check your starting inventory, you learn that you have “no tea” and “a splitting headache.” Such mixing of the physical and the metaphysical amongst your possessions will also remain an ongoing theme.

Especially if you’re at all familiar with any of the other Hitchhiker’s manifestations, you probably won’t have too many problems getting out of the house and lying in front of Mr. Prosser’s bulldozer to stop (for the moment) the destruction of your house to make room for a new bypass. If you do misjudge things and get yourself killed, you get an early introduction to another of the game’s throughgoing traits: the narrator, or the computerized “game master” if you will, has a voice and personality all his own. Playing Hitchhiker’s is like having a conversation — often an infuriating one — with him.

>stand

The bulldozer driver gives a quick chew of his gum and slams in the clutch. The bulldozer piles into the side of your home.

Your home collapses in a cloud of dust, and a stray flying brick hits you squarely on the back of the head. You try to think of some suitable last words, but what with the confusion of the moment and the spinning of your head, you are unable to compose anything pithy and expire in silence.

>s

You keep out of this, you're dead. An ambulance arrives.

>don't panic

You keep out of this, you're dead and should be concentrating on developing a good firm rigor mortis. You are put in the ambulance, which drives away.

>pray

For a dead person you are talking too much. As the ambulance reaches the mortuary a fleet of Vogon Constructor ships unexpectedly arrives and demolishes the Earth to make way for a new hyperspace bypass.

We are about to give you your score. Put on your peril-sensitive sunglasses now. (Hit RETURN or ENTER when ready.) >

The narrator doesn’t just tell you what’s happening. He chats with you, messes with you, has fun at your expense, occasionally lies to you. This isn’t precisely new ground for Infocom; their games going back to Zork I had occasionally broken from being the neutral voice of the simulation to offer quips and funny responses. But it’s much, much more pronounced here, an integral part of the experience instead of just the odd response to the occasional misguided or intentionally bizarre input. A similar smart-alecky narrative voice was par for the course with other versions of Hitchhiker’s and, indeed, kind of Adams’s default persona as a writer. Certainly anyone who’s ever read a Dickens novel knows that a second- or third-person voice doesn’t mean the narrator isn’t a character in the work. But seeing it here… well, that feels significant for anyone who’d like to see interactive fiction as a defensible literary form. Chalk that up as a big step forward.

So, Ford Prefect arrives just as expected to return your towel preparatory to getting off this rock before the Vogons blow it up to make way for a hyperspace bypass. If you haven’t experienced it already, here you are also introduced to another dominant trait: the game’s often arbitrary cruelty. If you simply take the towel Ford offers, he marches away, the Vogons arrive, and it’s game over. No, you have to refuse the towel to force Ford to actually notice your situation and come to the snap decision to take you with him.[6]Ford Prefect’s name, by the way, is one of the subtler jokes in Hitchhiker’s, and one that was entirely lost on American readers. The Ford Prefect, you see, was once a model of automobile in Britain. When the Betelgeusian Ford Prefect chose the name as “nicely inconspicuous,” he did so because he had, as Adams himself later clarified, “mistaken the dominant life form” on the planet.

Ford convinces Prosser to take your place in front of the bulldozer, just like in the other Hitchhiker’s manifestations. You head for the pub, where you drink beer to fortify yourselves for the matter transference beam. Then Prosser wises up and knocks down your house after all, prompting you, reenacting the role of the Arthur you remember from the book, to run screaming out of the pub. On the way you meet a hungry dog, who is key to one of the most legendarily cruel puzzles in the game. You need to feed him. As for why… well, that you won’t learn until much later. Then the Vogons show up with appropriate pomp and circumstance, and you and Ford have a bare instant to make your escape.

You wake up in darkness. The puzzle that follows can almost be read as an homage to the original Adventure, which had a maze for which close reading was similarly key. It’s early evidence of another trait of Hitchhiker’s: a tendency to evoke and occasionally subvert the adventuring heritage that preceded it. For instance, it will later hit you with a blessedly fake maze. As David Lebling recently put it, the form by 1984 was old and established enough that it could be parodied.

>z

You can hear nothing, smell nothing, taste nothing, see nothing, feel nothing, and are not even certain who you are.

>z

There's nothing you can taste, nothing you can see, nothing you can hear, nothing you can feel, nothing you can smell, you do not even know who you are.

>z

There's nothing you can taste, nothing you can see, nothing you can hear, nothing you can feel, nothing you can smell, you do not even know who you are.

>z

You can see nothing, feel nothing, hear nothing, taste nothing, and are not entirely certain who you are.

>smell

(darkness)

It does smell a bit. There's something pungent being waved under your nose. Your head begins to clear. You can make out a shadow moving in the dark.

>examine shadow

The shadow is vaguely Ford Prefect-shaped.

Vogon Hold

This is a squalid room filled with grubby mattresses, unwashed cups, and unidentifiable bits of smelly alien underwear. A door lies to port, and an airlock lies to starboard.

In the corner is a glass case with a switch and a keyboard.

It looks like the glass case contains:

an atomic vector plotter

Along one wall is a tall dispensing machine.

Ford removes the bottle of Santraginean Mineral Water which he's been waving under your nose. He tells you that you are aboard a Vogon spaceship, and gives you some peanuts.

That “tall dispensing machine” marks the most famous puzzle ever to appear in an Infocom game, or in any text adventure by anyone for that matter. A whole mythology sprung up around it. Infocom did a booming business for a while in “I got the babel fish!” tee-shirts, while it’s still mentioned from time to time today — sometimes, one suspects, by folks who actually know it only as a trope — as the ultimate in cruel puzzles. Yet I’ve always been a bit nonplussed by its reputation. Oh, getting the babel fish from dispenser to auditory canal is a difficult, convoluted game of Mouse Trap which is made yet more difficult by the facts that the dispenser has only a limited number of fish and you have only a limited number of turns in which to work before you’re hauled off to the Vogon captain’s poetry reading. Still, solving this puzzle is far from an insurmountable task. You’re given good feedback upon each failure as to exactly what happened to intercept the babel fish on its journey, while your scope of possibility is somewhat limited by the fact that this is still quite early in the game, when there aren’t yet that many objects to juggle. I feel like its reputation probably stems from this fact that it’s met so early in the game. Thus even most casual players did encounter it — and, it being the first really difficult puzzle, and one of the first for which prior knowledge of the other Hitchhiker’s manifestations was of no use, many or most of those players likely never got any further. The Imps have often noted that most people never finished most of the Infocom games they bought. What with its mass appeal to people who knew nothing of Infocom or adventure games thanks to the license as well as its extreme difficulty, one would presume that Hitchhiker’s had an even more abysmal rate of completion than the norm.

Since solving the babel-fish puzzle[7]Or not. is something of a rite of passage for all adventurers, I won’t totally spoil it here. I will note, however, that the very last step, arguably the most difficult of all, was originally even more difficult.

A small upper-half-of-the-room cleaning robot flies into the room, catches the babel fish (which is all the flying junk it can find), and exits.

The original version didn’t have that crucial parenthesis; it was wisely added at the insistence of Mike Dornbrook, who felt the player deserved just a little nudge.

The babel fish, of course, lets you understand the Vogon language, which is in turn key to getting that atomic vector plotter that is for some reason on display under glass amidst the “smelly bits of alien underwear.” Also key to that endeavor is the Vogon poetry reading to which you’re soon subjected.[8]The original Hitchhiker’s radio serial mentions Vogon poetry as the third worst in the universe. The second is that of the Azgoths of Kria, while the first is that of Paul Neil Milne Johnstone of Earth. Rather astoundingly, Johnstone is actually a real person, a bunk mate of Adams’s back at Brentwood School who would keep him awake nights “scratching this awful poetry about swans and stuff.” Now, it was kind of horrible of Adams to call him out like that (and probably kind of horrible for me to tell this story now), but it just keeps getting better. Poor Johnstone, who was apparently an earnest poet into adult life but not endowed with much humor not of the unintentional stripe, wrote a letter to Time Out magazine that’s as funny as just about anything in Hitchhiker’s:

“Unfortunate that Douglas Adams should choose to reopen a minor incident; that it remains of such consequence to him indicates a certain envy, if not paranoia. Manifest that Adams is being base-minded and mean-spirited, but it is surely unnecessary for Steve Grant [a journalist to whom Adams had told the story] to act as a servile conduit for this pettiness.”

With Johnstone’s lawyers beginning to circle, Paul Neil Milne Johnstone became Paula Nancy Millstone Jennings in the book and later adaptations. What you’re confronted with here is a puzzle far more cruel in my eyes than the babel-fish puzzle. It’s crucial that you get the Vogon captain to extend his reading to two verses; let’s not get into why. Unfortunately, at the end of the first verse he remarks that “you didn’t seem to enjoy my poetry at all” and has you tossed out the airlock. The solution to this conundrum is a bit of lateral thinking that will likely give logical, object-focused players fits: you just have to “ENJOY POETRY.”

>enjoy poetry

You realise that, although the Vogon poetry is indeed astoundingly bad, worse things happen at sea, and in fact, at school. With an effort for which Hercules himself would have patted you on the back, you grit your teeth and enjoy the stuff.

I’m not sure how to feel about this. It’s undeniably clever, and almost worth any pain for the great line “worse things happen at sea, and in fact, at school.” But at heart it’s guess-the-verb, or at least guess-the-phrase, a rather shocking thing to find in an Infocom game of 1984. Now maybe my description of Hitchhiker’s as both progressive and regressive starts to become clearer, as does Dornbrook’s assertion that Adams pushed Meretzky to “break the rules.” A comparison with the babel-fish puzzle shows Hitchhiker’s two puzzling personalities at their extremes. For all its legendary difficulty, the babel-fish puzzle feels to me like a vintage Meretzky puzzle: intricate but logical, responsive to careful reading and experimentation. “ENJOY POETRY,” on the other hand, is all Adams. You either make the necessary intuitive leap or you don’t. If you do, it’s trivial; if you don’t, it’s impossible.

In the session I played before writing this article, something else happened in the midst of the poetry-as-torture-device. Suddenly this long piece of text appeared, apropos of nothing going on at the time:

It is of course well known that careless talk costs lives, but the full scale of the problem is not always appreciated. For instance, at the exact moment you said "look up vogon in guide" a freak wormhole opened in the fabric of the space-time continuum and carried your words far far back in time across almost infinite reaches of space to a distant galaxy where strange and warlike beings were poised on the brink of frightful interstellar battle.

The two opposing leaders were meeting for the last time. A dreadful silence fell across the conference table as the commander of the Vl'Hurgs, resplendent in his black jewelled battle shorts, gazed levelly at the G'Gugvunt leader squatting opposite him in a cloud of green, sweet-smelling steam. As a million sleek and horribly beweaponed star cruisers poised to unleash electric death at his single word of command, the Vl'Hurg challenged his vile enemy to take back what it had said about his mother.

The creature stirred in its sickly broiling vapour, and at that very moment the words "look up vogon in guide" drifted across the conference table. Unfortunately, in the Vl'hurg tongue this was the most dreadful insult imaginable, and there was nothing for it but to wage terrible war for centuries. Eventually the error was detected, but over two hundred and fifty thousand worlds, their peoples and cultures perished in the holocaust.

You have destroyed most of a small galaxy. Please pick your words with greater care.

It incorporates an invalid input I had tried earlier, an attempt to look something up in the in-game version of the Hitchhiker’s Guide using syntax the game didn’t much like.[9]It’s fairly persnickety here; you can only “CONSULT GUIDE ABOUT” things. The little story is funny, especially if you haven’t recently read the novel version of Hitchhiker’s; it’s lifted verbatim from a passing riff near the end of the book, with only your invalid input replacing the novel’s version of Arthur’s comment that “I seem to be having tremendous difficulty with my lifestyle.”[10]Indeed, it seems to go relatively unremarked just how much text in the game is lifted directly from the novel, another artifact perhaps of the sheer difficulty of getting original prose out of Adams. More interesting to me, however, is what it represents conceptually. In incorporating a spurious input into the story in this way, it represents a sort of breaking of the fourth wall — a fascinating development in light of the fact that Infocom had spent a great deal of effort building said wall in the first place. By the time of Hitchhiker’s they scrupulously distinguished between what I’ll refer to as diegetic commands (things that cause things to happen in the storyworld) and non-diegetic — or, if you like, utility — commands (things like “SAVE” or “RESTORE” or, indeed, invalid inputs that don’t affect the storyworld). For instance, time passes in the story and the turn counter advances only in the case of the former. Infocom’s goal had long ago become to separate the undesirable challenge of interacting with the parser from the desirable one of interacting with the storyworld. Now along comes Adams to muddy it all up again. The difference, of course, is that early text adventures confused the layers of interface and simulation because they didn’t entirely know what they were doing. Adams and Meretzky break the formal rules the way artists do — consciously.

That’s not the end of the fellow in the jeweled battle shorts and his buddy; you’ll be meeting them again soon. But in the meantime you’re thrown out of the Vogon airlock[11]Although hopefully not before collecting the essential atomic vector plotter and picked up at the last possible second by the Heart of Gold, thanks to the magic of Infinite Improbability Physics. You end up in Darkness again, a motif that will continue to recur. You come out of it via another of the game’s most storied bits, the first of two incidents of it flat-out lying to you:

>listen

(to darkness)

You hear the deep and distant hum of a star drive coming from far above. There is an exit to port.

>w

You can't go that way.

>n

You can't go that way.

>s

(We were lying about the exit to port.) You emerge from a small doorway...

Entry Bay Number Two

This is an entry bay for the Heart of Gold. A corridor lies aft of here.

There is a sales brochure here.

"This looks like that incredible new Infinite Improbability Drive spaceship, the Heart of Gold!" says Ford, with growing excitement.

"Announcement, announcement. This is Eddie (the shipboard computer). We have just picked up two hitchhikers at an improbability factor of 2 to the 21,914 power to 1 against."

Just as you’d expect from the novel, you soon meet the masters of the Heart of Gold, two-headed party fiend Zaphod Beeblebrox and his Earthling girlfriend Trillian, née Tricia McMillan, whom you (Arthur) once tried to pick up at a party in London only to watch her leave with Zaphod.[12]I’ve always found Zaphod a hilarious character because he was such a walking, talking anachronism even in the early 1980s. He’s just so obviously a creature of the 1970s, from his hippy-dippy diction to his easygoing, lackadaisically stoned take on existence. He’d fit right in in Dazed and Confused. But from here things suddenly diverge from the novel. Your companions all bugger off to the sauna, conveniently removing themselves from the implementation equation and leaving you to explore the Heart of Gold and, eventually, a number of other realities to obtain a collection of tools,[13]Don’t ask. a collection of fluff,[14]Really don’t ask. and, stereotypical Englishman that you are, a good cup of tea. Ford helpfully leaves his copy of the Guide with you; you can “CONSULT” it about an impressive number of things. Some of these entries are just meant for fun, although they are once again often just recycled bits from the book. At least a few, however, are essential reading.

The Heart of Gold also contains the second instance of the game lying to you, this one much more extended.

>u

Corridor, Aft End

This is one end of a short corridor that continues fore along the main deck of the Heart of Gold. Doorways lead to aft and port. In addition, a gangway leads downward.

>s

That entrance leads to the Infinite Improbability Drive chamber. It's supposed to be a terribly dangerous area of the ship. Are you sure you want to go in there?

>yes

Absolutely sure?

>yes

I can tell you don't want to really. You stride away with a spring in your step, wisely leaving the Drive Chamber safely behind you. Telegrams arrive from well-wishers in all corners of the Galaxy congratulating you on your prudence and wisdom, cheering you up immensely.

>s

What? You're joking, of course. Can I ask you to reconsider?

>no

Engine Room

You're in the Infinite Improbability Drive chamber. Nothing happens; there is nothing to see.

>l

Engine Room

I mean it! There's nothing to see here!

>l

Engine Room

Okay, okay, there are a FEW things to see here. This is the room that houses the powerful Infinite Improbability Generator that drives the Heart of Gold. An exit lies fore of here.

Sitting in the corner is a spare, portable Improbability Generator.

There is an ionic diffusion rasp here.

There is a pair of hypersonic pliers here.

(Footnote 10)

>footnote 10

I guess it isn't all that dangerous a place after all.

Those footnotes which pop up from time to time are another of the game’s blizzard of new ideas — rather pointless really, but good fun.[15]Like (hopefully) the ones I’ve included in this article in homage. Or maybe this is my bid for literary greatness via my own version of Pale Fire.

If you experiment and use the Guide wisely, you’ll eventually find a way to transport yourself into about half a dozen little vignettes, sometimes still in the person of Arthur, sometimes in that of one of your three companions currently slumming it in the sauna. I won’t belabor most of these; this article has to end at some point, after all, and if you do play for yourself you deserve to discover something for yourself. But I do want to talk just a bit about one, or rather two that are closely interrelated, because they involve a puzzle often cited as an example of Hitchhiker’s extreme, downright un-Infocom-like cruelty.

One of the vignettes features our friend of the jeweled battle shorts. It seems that he and his erstwhile enemy have worked out the source of the misunderstanding that led to all those centuries of terrible war: a creature from Earth.[16]This would seem to belie the Guide‘s description of Earth as “harmless,” and even the revised description of it as “mostly harmless.” You’re transported onto the bridge of his flagship as he and his erstwhile enemy hurtle toward your planet, not yet destroyed by the Vogons in this vignette,[17]There’s a joke, or maybe an aphorism, in there somewhere. “Between a Vl’Hurg and a Vogon,” maybe? with malice in their hearts.

War Chamber

Spread before you, astonishingly enough, is the War Chamber of a star battle cruiser. Through the domed canopy of the ship you can see a vast battle fleet flying in formation behind you through the black, glittering emptiness of space. Ahead is a star system towards which you are hurtling at a terrifying speed.

There is an ultra-plasmic vacuum awl here.

Standing near you are two creatures who are gazing at the star system with terrible hatred in their eyes. One is wearing black jewelled battle shorts, and the other is wreathed in a cloud of green, sweet-smelling steam. They are engaged in conversation.

The fleet continues to hurtle sunwards.

If you’re like, oh, about 95% of players, your journey will end abruptly when the battle fleet, which in a fatal oversight on the part of our militant alien friends turns out to be microscopic by the scale of the Earth, is swallowed by a small dog. To prevent this, you needed to have taken the unmotivated (at the time) step of feeding something to the aforementioned dog way back on Earth in the first act of the game, before the Vogons arrived. Horribly cruel, no? Well, yes and no. Another of the vignettes — they appear in random order, thus justifying Meretzky’s assertion that Hitchhiker’s ends up representing one of the “most ruthlessly nonlinear designs we [Infocom] ever did” — has you replaying the opening sequence of the game again, albeit from the perspective of Ford Prefect. You can also feed the dog there. If you fail at a vignette, meanwhile — and that’s very easy to do — you usually “die,” but that’s not as bad as you might expect. You’re merely returned to the Heart of Gold, and can have another go at it later. This mechanism saves Hitchhiker’s repeatedly, and not least in the case of this puzzle, from accusations of relying on extensive learning by death.

Still, there should be no mistake: Hitchhiker’s is punishingly difficult for even the most experienced of adventurers, the most challenging Infocom release since Suspended and the one with the most elements of, shall we say, questionable fairness since the days of Zork II and Deadline. While it is possible to repeat the vignettes until you solve each overarching challenge, it’s painfully easy to leave small things undone. Having “solved” the vignette in the sense of completing its overarching goal, you’re then locked out of experiencing it again, and thus locked out of victory for reasons that are obscure indeed.[18]Zaphod’s sequence is particularly prone to this, to the extent that I’ll offer a hint: look under the seat! One or two puzzles give no immediate feedback after you solve them, which can lead you to think you’re on the wrong track.[19]I’m thinking particularly of growing the plant here. For virtually the entire game after arriving on the Heart of Gold you labor away with no clear idea what it is you’re really supposed to be accomplishing. Sometimes vital properties of things go undescribed just for the hell of it.[20]I’m speaking particularly of the brilliantly Adamsian “thing your aunt gave you that you don’t know what it is,” of which it’s vital to know — take this as another tip — that you can put things inside it, even though that’s never noted or implied by its description. And then many of these puzzles are… well, they’re just hard, and at least as often hard in the way of “ENJOY POETRY” as in the way of the babel fish. The “Standard” difficulty label on the box, which was placed there purely due to marketing needs, is the cruelest touch of all.

So, we must ask just how Hitchhiker’s became such an aberration in the general trend of Infocom games to become ever fairer and, yes, easier. Meretzky noted that trend in his interview for Get Lamp and was not, either back in the day or at the time of his interview, entirely happy about it. He felt that wrestling with a game for weeks or months until you had that “Eureka!” moment in the bathtub or the middle of a working day was a huge part of the appeal of the original Zork — an appeal that Infocom was gradually diluting. Thus Meretzky and Adams explicitly discussed his opinion that “adventure games were becoming a little too easy,” and that Hitchhiker’s could be a corrective to that. Normally puzzles that were exceptionally difficult had their edges rounded during Infocom’s extensive testing process. But that didn’t happen for Hitchhiker’s to the extent that it normally did, for a couple of reasons. First, many of these puzzles had been written not by any ordinary Imp but by Douglas Adams; for obvious reasons, Infocom was reluctant to step on his toes. Additionally, the testers didn’t have nearly as much time with Hitchhiker’s as with an ordinary Infocom game, thanks to Adams’s procrastination and the resultant delays and Infocom’s determination to get the game out in time for Christmas. The testers did a pretty good job with the purely technical side; even the first release of Hitchhiker’s is not notably buggy. But there wasn’t time for the usual revisions to the design as a whole even had there been a strong motivation to do them from Infocom’s side. Any lack of such motivation was not down to lack of complaining from the testers: Meretzky admits that they “strongly urged that the game be made easier.”

The decision to go ahead with such a cruel design has been second-guessed by folks within Infocom in the years since, especially in light of the declining commercial fortunes of the company’s post-Hitchhiker’s era. Jon Palace presented a pretty good summary of the too-difficult camp’s arguments in his own Get Lamp interview:

Some have argued that The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was one of the biggest mistakes we made because it introduced a huge audience to a relatively difficult game. The difficulty of the game and its design flaws[21]Palace was no fan of the dog-feeding puzzle in particular. may have turned off the largest new audience we could have had. Perhaps we should have made that game a lot easier. It’s very funny, and it’s got some terrific puzzles. But my point is that if it was the first time people were experiencing an Infocom game, because of the names “Hitchhiker’s Guide” and “Douglas Adams,” there was only so much Douglas Adams they could get out of it without working harder than they wanted to.

Steve Meretzky, on the other hand, remains unrepetant, as do Mike Dornbrook and others. Dornbrook’s argument, which strikes me as flawed, is essentially that most people didn’t finish most Infocom games anyway — even the easier ones — so Hitchhiker’s difficulty or hypothetical lack thereof didn’t make much difference. I suppose your attitude toward these issues says much about what you want Infocom’s games to be: accessible interactive stories with a literary bent or intricate puzzle boxes. It’s Graham Nelson’s memorable description of interactive fiction as a narrative at war with a crossword writ large yet again. For my part, I think interactive fiction can be either, an opinion apparently shared by Meretzky himself, the man who went on to write both the forthrightly literary A Mind Forever Voyaging and the unabashed puzzle box that is Zork Zero. Yet I do demand that my puzzle boxes play fair, and find that Hitchhiker’s sometimes fails me here. And while I have no objection to the concept of a tougher Infocom game for the hardcore who cut their teeth on Zork,[22]See 1985’s Spellbreaker, which unlike Hitchhiker’s was explicitly billed as exactly that and does a superb job at it. I’m not sure that Hitchhiker’s should have been that game, for the obvious commercial considerations Palace has just outlined for us.

And yet, and yet… it’s hard to see how some of the more problematic aspects of Hitchhiker’s could be divorced from its more brilliant parts. As a final example of that, I want to talk about — and, yes, spoil — one last puzzle, one of the last in the game in fact. By now you’ve collected all of the various bits and pieces from the vignettes and the narrative of the game has rejoined that of the book; the Heart of Gold has landed on the legendary lost planet of Magrathea. You’ve also managed to brew yourself a nice hot cup of tea. Now you need to get inside the room of Marvin the Paranoid Android to convince him to open the ship’s hatch to let you go exploring.

>s

Corridor, Aft End

This is one end of a short corridor that continues fore along the main deck of the Heart of Gold. Doorways lead to aft and port. In addition, a gangway leads downward.

>w

The screening door is closed.

>open door

The door explains, in a haughty tone, that the room is occupied by a super-intelligent robot and that lesser beings (by which it means you) are not to be admitted. "Show me some tiny example of your intelligence," it says, "and maybe, just maybe, I might reconsider."

>consult guide about intelligence

The Guide checks through its Sub-Etha-Net database and eventually comes up with the following entry:

Thirty million generations of philosophers have debated the definition of intelligence. The most popular definition appears in the Sirius Cybernetics Corporation android manuals: "Intelligence is the ability to reconcile totally contradictory situations without going completely bonkers -- for example, having a stomach ache and not having a stomach ache at the same time, holding a hole without the doughnut, having good luck and bad luck simultaneously, or seeing a real estate agent waive his fee."

>get no tea

no tea: Taken.

>i

You have:

no tea

tea

a flowerpot

The Hitchhiker's Guide

a towel

a thing your aunt gave you which you don't know what it is

a babel fish (in your ear)

your gown (being worn)

>open door

The door is almost speechless with admiration. "Wow. Simultaneous tea and no tea. My apologies. You are clearly a heavy-duty philosopher." It opens respectfully.

I’m not quite sure how you make that intuitive leap precisely fair, but I am pretty sure I wouldn’t want to live without it. Maybe Hitchhiker’s is fine just the way it is. Soon after, you drink that glorious cup of tea, a feat which, in possibly the most trenchant and certainly the funniest piece of social commentary on the nature of Britishness in the entire game, scores you a full 100 of the game’s total of 400 points. Soon after that you step onto the surface of Magrathea, where “almost instantly the most incredible adventure starts which you’ll have to buy the next game to find out about.” That game, of course, would never materialize. The ludic version of Arthur Dent has remained frozen in amber just outside the Heart of Gold for almost thirty years now, giving Hitchhiker’s claim to one final dubious title: that of the only game in the Infocom canon that doesn’t have an ending.

Crazy and vaguely subversive as it is, Hitchhiker’s would have a massive influence on later works of interactive fiction. Contemporaneous Infocom games are filled with what feels to modern sensibilities like an awful lot of empty rooms that exist only to be mapped and trekked across. Hitchhiker’s, on the other hand, is implemented deeply rather than widely. There are just 31 rooms in the entire game, but virtually every one of them has interesting things to see and do within it. Further, these 31 rooms come not in a single contiguous and unchanging block, but a series of linked dramatic scenes. The Heart of Gold, which contains all of nine rooms, is by far the biggest contiguous area in the game. Hitchhiker’s can thus lay pretty good claim to being the first text adventure to completely abandon the old obsession with geography that defined the likes of Adventure and Zork. Certainly it’s the first Infocom game in which map-making is, even for the most cartographically challenged amongst us, utterly superfluous. This focus on fewer rooms with more to do in them feels rather shockingly modern for a game written in 1984. Ditto the dynamism of most of the scenes, with things always happening around you that demand a reaction. The only place where you can just explore at your leisure is the Heart of Gold.

Many a later game, including such 1990s classics as Curses, Jigsaw, and The Mulldoon Legacy, have used linked vignettes like those in Hitchhiker’s to send the player hopscotching through time and space. More have followed its lead in including books and other materials to be “CONSULT”ed. Even a fair number[23]Not to mention this post. have latched onto the pointless but somehow amusing inclusion of footnotes. Less positively, quite a number of games both inside the interactive-fiction genre and outside of it have tried very hard to mimic Adams’s idiosyncratic brand of humor, generally to less than stellar effect.[24]Tolkien is about the only other generally good author I can think of who has sparked as much bad writing as Adams.

Hitchhiker’s is an original, with a tone and feel unique in the annals of interactive fiction. It breaks the rules and gets away with it. I’m not sure prospective designers should try to copy it in that, but they certainly should play it, as should everyone interested in interactive fiction. It’s easily one of the dozen or so absolutely seminal works in the medium. Fortunately, it’s also the most effortless of all Infocom games to play today, as the BBC has for some years now hosted an online version of it. Yes, there’s lots of graphical gilding around the lily, but at heart it’s still the original text adventure. If you’re interested enough in interactive fiction to make it this far in this article and you still haven’t played it, by all means remedy that right away.

(In addition to the various Get Lamp interviews, Steve Meretzky’s interview in the book Game Design Theory and Practice was very valuable in writing this article.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | “As seen on Tri-D!” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Easily mistaken for an empty plastic baggie. |

| ↑3 | They turn opaque when danger is at hand to avoid upsetting your delicate sensibilities. The ones in the game package are, naturally, made of black construction paper. |

| ↑4 | These were manufactured in huge quantities and given away for some time at trade shows and the like as well as being inserted into game boxes. |

| ↑5 | Or whatever it’s supposed to be. |

| ↑6 | Ford Prefect’s name, by the way, is one of the subtler jokes in Hitchhiker’s, and one that was entirely lost on American readers. The Ford Prefect, you see, was once a model of automobile in Britain. When the Betelgeusian Ford Prefect chose the name as “nicely inconspicuous,” he did so because he had, as Adams himself later clarified, “mistaken the dominant life form” on the planet. |

| ↑7 | Or not. |

| ↑8 | The original Hitchhiker’s radio serial mentions Vogon poetry as the third worst in the universe. The second is that of the Azgoths of Kria, while the first is that of Paul Neil Milne Johnstone of Earth. Rather astoundingly, Johnstone is actually a real person, a bunk mate of Adams’s back at Brentwood School who would keep him awake nights “scratching this awful poetry about swans and stuff.” Now, it was kind of horrible of Adams to call him out like that (and probably kind of horrible for me to tell this story now), but it just keeps getting better. Poor Johnstone, who was apparently an earnest poet into adult life but not endowed with much humor not of the unintentional stripe, wrote a letter to Time Out magazine that’s as funny as just about anything in Hitchhiker’s:

“Unfortunate that Douglas Adams should choose to reopen a minor incident; that it remains of such consequence to him indicates a certain envy, if not paranoia. Manifest that Adams is being base-minded and mean-spirited, but it is surely unnecessary for Steve Grant [a journalist to whom Adams had told the story] to act as a servile conduit for this pettiness.” With Johnstone’s lawyers beginning to circle, Paul Neil Milne Johnstone became Paula Nancy Millstone Jennings in the book and later adaptations. |

| ↑9 | It’s fairly persnickety here; you can only “CONSULT GUIDE ABOUT” things. |

| ↑10 | Indeed, it seems to go relatively unremarked just how much text in the game is lifted directly from the novel, another artifact perhaps of the sheer difficulty of getting original prose out of Adams. |

| ↑11 | Although hopefully not before collecting the essential atomic vector plotter |

| ↑12 | I’ve always found Zaphod a hilarious character because he was such a walking, talking anachronism even in the early 1980s. He’s just so obviously a creature of the 1970s, from his hippy-dippy diction to his easygoing, lackadaisically stoned take on existence. He’d fit right in in Dazed and Confused. |

| ↑13 | Don’t ask. |

| ↑14 | Really don’t ask. |

| ↑15 | Like (hopefully) the ones I’ve included in this article in homage. Or maybe this is my bid for literary greatness via my own version of Pale Fire. |

| ↑16 | This would seem to belie the Guide‘s description of Earth as “harmless,” and even the revised description of it as “mostly harmless.” |

| ↑17 | There’s a joke, or maybe an aphorism, in there somewhere. “Between a Vl’Hurg and a Vogon,” maybe? |

| ↑18 | Zaphod’s sequence is particularly prone to this, to the extent that I’ll offer a hint: look under the seat! |

| ↑19 | I’m thinking particularly of growing the plant here. |

| ↑20 | I’m speaking particularly of the brilliantly Adamsian “thing your aunt gave you that you don’t know what it is,” of which it’s vital to know — take this as another tip — that you can put things inside it, even though that’s never noted or implied by its description. |

| ↑21 | Palace was no fan of the dog-feeding puzzle in particular. |

| ↑22 | See 1985’s Spellbreaker, which unlike Hitchhiker’s was explicitly billed as exactly that and does a superb job at it. |

| ↑23 | Not to mention this post. |

| ↑24 | Tolkien is about the only other generally good author I can think of who has sparked as much bad writing as Adams. |