Bob Bates, the last person in history to author an all-text Infocom adventure game, came to that achievement by as circuitous a path as anyone in a 1980s computer-game industry that was positively brimming with unlikely game designers.

Born in suburban Maryland in 1953, the fourth of the eventual eight children of James and Frances Bates, Bob entered Georgetown University on a partial scholarship in 1971 to pursue a dual major in Philosophy and Psychology. He was interested in people in the abstract, and this seemed the perfect combination of majors to pursue that interest. He imagined himself becoming a teacher. But as it turned out, the combination served equally well to prepare the unwitting Bob for a future in game design. At Georgetown, a Philosophy degree was a Bachelor of Arts, Psychology a Bachelor of Science, meaning he found himself taking a very unusual (and demanding) mixture of liberal-arts and hard-science courses. What better preparation can there be for the art and science of game design?

Unlike the majority of Georgetown students, Bob didn’t have a great deal of familial wealth at his disposal; it was only thanks to the scholarship that he could attend at all. Thus he was forced to take odd jobs throughout his time there just to meet the many demands of daily life that the scholarship didn’t cover. Early on in his time at university, he got a job in Georgetown’s Sports Information Department that carried with it a wonderful perk: he could attend sporting events for free. When that job ended after about a year, Bob, a big sports fan, was left trying to scheme another way to get into the events. The solution he hit upon was working as a reporter for the sports department of the university newspaper. Access restored and problem solved.

The idea of becoming a writer had never resonated with Bob prior to coming to the newspaper, but he quickly found that he not only enjoyed it but was, at least by the accounts of the newspaper’s editors and readers, quite good at it. “That’s the point at which my aspiration switched,” says Bob, “from being a teacher to being a writer.” Soon he became sports editor, then the managing editor of the newspaper as a whole as well as the pseudonymous author of a humor column. His senior year found him editor-in-chief of the university’s yearbook.

Upon graduating from Georgetown in 1975, he still needed to earn money. On a job board — a literal job board in those days — he saw a posting for a tour guide for the Washington, D.C., area. The job entailed managing every aspect of group tours that were made up of folks from various clubs and organizations, from schoolchildren to senior citizens. Bob would be responsible for their entire experience: meeting them at the airport, making sure all went well at the hotel, shepherding them from sight to sight, answering all of their questions and dealing with all of their individual problems. Just as his experience at the newspaper had taught him to love the act of writing, Bob found that working as a tour guide uncovered another heretofore unknown pleasure and talent that would mark his future career: “explaining places and history to people, explaining what happened and where it happened.” “These places were interesting to me, and therefore I tried to make them interesting for other people,” he told me — an explanation that applies equally to his later career as an adventure-game designer, crafting games that more often than not took place in existing settings drawn from the pages of history or fiction.

For Bob the aspiring writer, the working schedule of a tour guide seemed ideal. While he would have to remain constantly on the clock and on-hand for his clients during each tour of anywhere from three to seven days, he could then often take up to two weeks off before the next. The freedom of having so many days off could give him, or so he thought, the thing that every writer most craves: the freedom to write, undisturbed by other responsibilities.

Still, the call of the real world can be as hard for a writer as it can for anyone else to resist. Bob found himself getting more and more involved in the day-to-day business of the company; soon he was working in the office instead of in the field, striking up his own network of contacts with clients. At last, feeling overworked and under-compensated for his efforts, he founded a tour company of his own, one that he built in a very short period of time into the largest of its type in Washington, D.C.

By 1983, now married and with his thirtieth birthday fast approaching, Bob felt himself to be at something of a crossroads in life. Plenty of others — probably the vast majority — would have accepted the thriving tour company and the more than comfortable lifestyle that came with it, would have put away those old dreams of writing alongside other childish things. Bob, however, couldn’t shake the feeling that this wasn’t all he wanted from life. He sold the company to one of its employees when he was still a few weeks shy of his thirtieth birthday in order to write The Great American Novel — or, at any rate, an American novel.

The novel was to have been a work of contemporary fiction called One Nation Under God, an examination of the fraught topic, then and now, of prayer in American public schools, along with the more general mixing of politics and religion in American society — of which mixing Bob, then and now, is “extremely not in favor.” The story would involve a group of schoolchildren who came to Washington, D.C., on a tour — “that would be the write what you know part of the exercise,” notes Bob wryly — and got caught up in the issue.

But nearly two years into the writing, the novel still wasn’t even half done, and he still didn’t even have a contract to get it published. He reluctantly began to consider that, while he was certainly a writer, he might not be a novelist. “I need to find a different way to make money from this writing business,” he thought to himself. And then one day he booted up Zork, and the wheels started turning.

The edition of Zork in question ran on an old Radio Shack TRS-80 which Bob’s dad had given him to use as a replacement for the typewriter on which he’d been writing thus far. Bob had not heretofore had any experience with or interest in computers — he gave up his beloved old Selectric typewriter only very reluctantly — but he found Zork surprisingly intriguing. The more he played of it, the more he thought that this medium might give him an alternative way of becoming a writer, one with a much lower barrier to entry than trying to convince a New York literary agent to take a chance on a first-time novelist.

A lifelong fan and practitioner of barbershop harmony, Bob was singing at the time with a well-known group called the Alexandria Harmonizers. Another member, with whom Bob had been friends for some time, was a successful businessman named Dave Wilt, owner of a consulting firm. An odd remark that Dave had once made to him kept coming back to Bob now: “If you’re ever interested in starting a business, we should talk.” When Bob screwed up his courage and proposed to Dave that they start a company together to compete with Infocom, the latter’s response was both positive and immediate: “Yes! Let’s do that!”

While he had little personal interest in the field of computer gaming, Dave Wilt did have a better technical understanding of computers than Bob. Most importantly, he had access to systems and programmers, both through his own consulting firm and in the person of his brother Frederick, a professional programmer. A three-man team came together in some excess office space belonging to the Wilts: Dave Wilt as manager and all-around business guy, Frederick Wilt as programmer and all-around technical guy, and Bob as writer and designer.

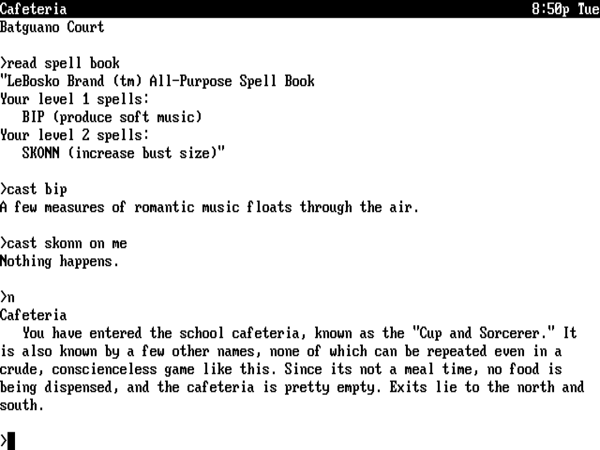

They decided to call their little company Challenge, Inc. Ironically in light of Bob’s later reputation as a designer of painstakingly fair, relatively straightforward adventure games, the name was carefully chosen. “If you think an Infocom game is hard,” went their motto, “wait until you try a Challenge game!” A connoisseur of such hardcore puzzles as the cryptic crosswords popular in Britain, Bob wanted to make their text-adventure equivalent. In commercial terms, “it was exactly the wrong idea at the wrong time,” admits Bob. It was also an idea that could and very likely would have gone horribly, disastrously wrong in terms of game design. If there’s a better recipe for an unplayable, insoluble game than a first-time designer setting out to make a self-consciously difficult adventure, I certainly don’t know what it is. Thankfully, Infocom would start walking Bob back from his Challenging manifesto almost from the instant he began working with them.

The deal that brought Challenge, Infocom’s would-be competitor, into their arms came down to a combination of audacity and simple dumb luck. It was the Wilts who first suggested to Bob that, rather than trying to write their own adventuring engine from scratch, they should simply buy or license a good one from someone else. When Dave Wilt asked Bob who might have such a thing to offer, Bob replied that only one company could offer Challenge an engine good enough to compete with Infocom’s games: Infocom themselves. “Well, then, just call them up and tell them you want to license their engine,” said Dave. Bob thought it was a crazy idea. Why would Infocom license their engine to a direct competitor? “Just call them!” insisted Dave. So, Bob called them up.

He soon was on the phone with Joel Berez, recently re-installed as head of Infocom following Al Vezza’s unlamented departure. Berez’s first question had doubtless proved his last in many earlier such conversations: did Bob have access to a DEC minicomputer to run the development system? Thanks to the Wilts’ connections, however, Bob knew that they could arrange to rent time on exactly such a system. That hurdle cleared, Berez’s first offer was to license the engine in perpetuity for a one-time fee of $1 million, an obvious attempt, depending on how the cards fell, to either drive off an unserious negotiator or to raise some quick cash for a desperately cash-strapped Infocom. With nowhere near that kind of capital to hand, Bob countered with a proposal to license the engine on a pay-as-you-go basis for $100,000 per game. Berez said the proposal was “interesting,” said he’d be back in touch soon.

Shortly thereafter, Berez called to drop a bombshell: Infocom had just been bought by Activision, so any potential deal was no longer entirely in his hands. Jim Levy, president of Activision, would be passing through Dulles Airport next Friday. Could Bob meet with him personally there? “I can do that,” said Bob.

Levy came into the meeting in full-on tough-negotiator mode. “Why should we license our engine to you?” he asked. “You’ve never written a game. What makes you think you can do this?” But Bob had also come prepared. He pulled out a list of all of the games that Infocom had published. With no access to any inside information whatsoever, he had marked on the list the games he thought had sold the most and those he thought had sold the least, along with the reasons he believed that to be the case for each. Then he outlined a plan for Challenge’s games that he believed could place them among the bestsellers.

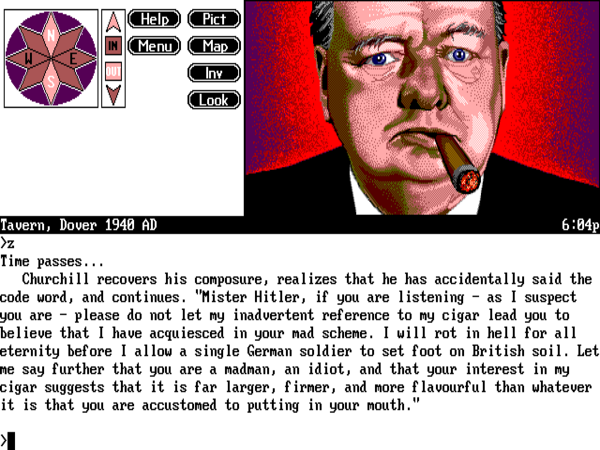

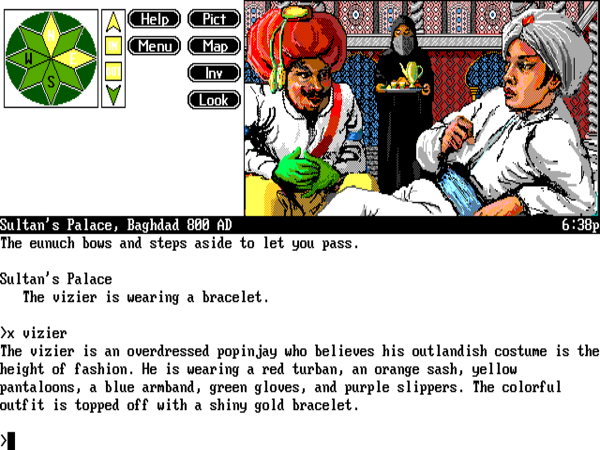

Bob’s plan set a strong precedent for his long career to come in game development, in which he would spend a lot of his time adapting existing literary properties to interactive mediums. Under the banner of Challenge, Inc., he wanted to make text-adventure adaptations of literary properties possessed of two critical criteria: a) that they feature iconic characters well-known to just about every person in the United States if not the world; and b) that they be out of copyright, thus eliminating the need to pay for licenses that Challenge was in no position to afford. He already had the subjects of his first three games picked out: Sherlock Holmes, King Arthur, and Robin Hood, in that order — all characters that Bob himself had grown up with and continued to find fascinating. All were, as Bob puts it, “interesting people in interesting places doing interesting things.” How could a budding game designer go wrong?

Levy was noncommittal throughout the meeting, but on Monday Bob got another call from Joel Berez: “Let’s forget this licensing deal. Why don’t you write games for Infocom?” Both Activision and Infocom loved Bob’s plan for making adventurous literary adaptations, even coming up with a brand name for a whole new subset of Infocom interactive fiction: “Immortal Legends.” The idea would only grow more appealing to the powers that were following Jim Levy’s ouster as head of Activision in January of 1987; his successor, Bruce Davis, brought with him a positive mania for licenses and adaptations.

We should take a moment here to make sure we fully appreciate the series of fortuitous circumstances that brought Bob Bates to write games for Infocom. Given their undisputed position of leadership in the realm of text adventures, Bob’s inquiry could hardly have been the first of its nature that Infocom had received. Yet Infocom had for years absolutely rejected the idea of working with outside developers. What made them suddenly more receptive was the desperate financial position they found themselves in following the Cornerstone debacle, a position that made it foolhardy to reject any possible life preserver, even one cast out by a rank unknown quantity like Bob Bates. Then there was the happenstance that gave Bob and the Wilts access to a DECsystem-20, a now aging piece of kit that had been cancelled by DEC a couple of years before and was becoming more and more uncommon. And finally there came the Activision purchase, and with it immediate pressure on Infocom from their new parent to produce many more games than they had ever produced before. All of these factors added up to a yes for Challenge after so many others had received only a resounding no.

In telling the many remarkable stories that I do on this blog, I’m often given cause to think about the humbling role that sheer luck, alongside talent and motivation and all the other things we more commonly celebrate, really does play in life. In light of his unique story, I couldn’t help but ask Bob about the same subject. I found his response enlightening.

In the course of my subsequent career, I ended up rubbing shoulders with lots of very, very well-known authors. Sitting with them informally at dinners and various events and listening to their stories, every single one of them would talk about “that stroke of luck” or “those strokes of luck” that plucked them from the pool of equally talented — or better talented — writers. Their manuscript landed on an editor’s desk at a certain day at a certain time. Or they bumped into somebody, or there was a chance encounter, etc. Every successful writer that I know will tell you that luck played a huge part in their success.

And I am no different. I have been extremely fortunate… but you know, that word “fortunate” doesn’t convey the same sense that “luck” does. I’ve been LUCKY.

With Infocom’s ZIL development system duly installed on the time-shared DEC to which Challenge had access — this marks the only instance of the ZIL system ever making it out of Massachusetts — Bob needed programmers to help him write his games, for Frederick Wilt just didn’t have enough time to do the job himself. Through the once timeless expedient of looking in the Yellow Pages, he found a little contract-programming company called Paragon Systems. They sent over a senior and a junior programmer, named respectively Mark Poesch and Duane Beck. Both would wind up programming in ZIL for Challenge effectively full-time.

Most of the expanded Challenge traveled up to Cambridge for an introduction to ZIL and the general Infocom way of game development. There they fell into the able hands of Stu Galley, the soft-spoken Imp so respected and so quietly relied upon by all of his colleagues. Stu, as Bob puts it, “took us under his wing,” a bemused Bob watching over his shoulder while he patiently walked the more technical types from Challenge through the ins and outs of ZIL.

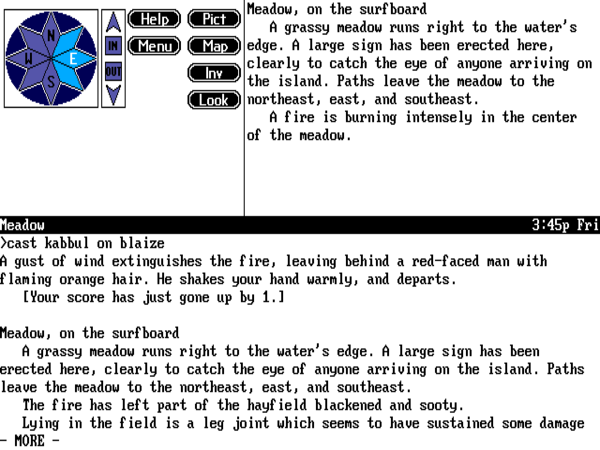

Infocom continued to give Bob and his colleagues much support throughout the development of the game that would become known as Sherlock: The Riddle of the Crown Jewels. It was for instance Infocom themselves who suggested that Sherlock become the second Infocom text adventure (after The Lurking Horror) to include sound effects, and who then arranged to have Russell Lieblich at Activision record and digitize them. Present only on the Amiga and Macintosh versions of the game, the sounds, ranging from Sherlock’s violin playing to the clip-clop of a hansom cab, are admittedly little more than inessential novelties even in comparison to those of The Lurking Horror.

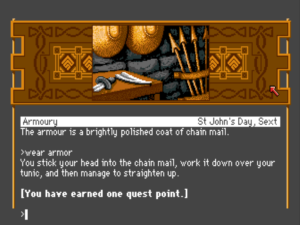

More essential was the support Infocom gave Bob and company in the more traditional aspects of the art and science of crafting quality adventure games. As I’ve occasionally noted before, the triumph of Infocom was not so much the triumph of individual design genius, although there were certainly flashes of that from time to time, as it was a systemic triumph. Well before the arrival of Challenge, Infocom had developed a sort of text-adventure assembly line that came complete with quality control that was the envy of the industry. Important as it was to all the games, Infocom’s dedication to the process was especially invaluable to first-time Imps like Bob. The disembodied genius of the process guided them gently away from the typical amateur mistakes found in the games of virtually all of Infocom’s peers — such as Bob’s early fixation on making a game that was gleefully, cruelly hard — and gave them the feedback they needed at every step to craft solid adventures. Sherlock was certainly an unusual game in some respects for Infocom, being the first to be written by outsiders, but in the most important ways it was treated just the same as all the others — not least the many rounds of testing and player feedback it went through. Even today, when quality control is taken much more seriously by game makers in general than it was in Infocom’s day, Infocom’s committed, passionate network of inside and outside testers stands out. Bob:

There’s something that distinguished Infocom from most other game companies that I’ve worked with — and I’ve since worked with a lot. The idea of the role of the tester in today’s game-development world is that a tester is somebody who finds bugs. Testing is in fact often outsourced. What people are looking for are situations where the game doesn’t work.

But testing at Infocom was a far more collaborative process between tester and designer, in terms of things that should be in the game and perhaps weren’t: “I tried to do this and it should have worked”; “This way of phrasing an input should work, but it didn’t.” GET THE ROCK should work just as well as PICK UP THE ROCK or TAKE THE ROCK or ACQUIRE THE ROCK or whatever. That applied not just to syntax, but to things like “It seems like this should be possible” or “You know, if you’ve got the player in this situation, they may well try to do X or Y.” We would look at transcripts at Infocom from testers. And we’d solicit qualitative comments as well as mechanical comments. If the machine crashed somewhere or kicked out an error message, of course I’m interested in that, but the Infocom testers would also offer qualitative input about the design of the game. That was special, and is not often the case today. I think that’s something that contributed greatly to the quality of Infocom’s games.

Bob remembers the relationship with everyone at Infocom, which he visited frequently throughout the development of Sherlock and the Challenge game that would follow it, as “really good — we liked each other, we liked talking with each other, I enjoyed visiting their offices and wanted to feel like a part of their culture. They accepted me as one of their own.” The lessons in professionalism and craft that Bob learned from Infocom would follow him through the rest of an impressive and varied career in making games. Bob:

They had the same persnicketiness to get things right that I had. For example, in Sherlock there was a puzzle that involved the tides in the Thames; the Thames goes up quite a bit, like six or seven feet in its tidal variation. In the Times newspaper included with the game, for which they got permission from the London Times to include excerpts from that day, we put in tide tables, and I remember huge arguments over whether they should be the actual tide tables from that day or whether we could bend them to suit the player — to have it work out so the player could solve this puzzle at a time that was convenient for the player, as opposed to when it was convenient for nature. Right now I don’t recall the resolution to that. I don’t remember who won.

My own amateurish investigations would seem to indicate that the tide tables were altered by several hours, although I’m far from completely confident in my findings. But the really important thing, of course, is that such a “persnickety” debate happened at all — a measure of all parties’ willingness to think deeply about the game they were making.

Like many of Bob Bates’s games, Sherlock isn’t one that lends itself overmuch to high-flown analysis, and this can in turn lead some critics to underestimate it. As in a surprising number of ludic Sherlock Holmes adaptations, you the player are cast in the role of the faithful Dr. Watson rather than the great detective himself — perhaps a wise choice given that Sherlock is so often little more than a walking, talking deus ex machina in the original stories, his intellectual leaps more leaps of pure fancy on Arthur Conan Doyle’s part than identifiable leaps of deduction. Sherlock effectively reverses the roles of Watson and Sherlock, rendering the latter little more than a sidekick and occasional source of clues and nudges in the game that bears his name.

It seems that Professor Moriarty has struck again, stealing nothing less than the Crown Jewels of England this time. He’s hidden them somewhere in London, leaving his old nemesis Sherlock a series of clues as to their location in the form of verse. To complete this highly unlikely edifice of artificial plotting, Sherlock decides to turn the investigation over to you, Watson, because Moriarty “will have tried to anticipate the sequence of my actions, and I’m sure he has laid his trap accordingly. But if you were to guide the course of our investigations, he will certainly be thrown off the scent. Therefore, let us take surprise onto our side and rely on your instincts as the man of action I know you to be — despite your frequent modest assertions to the contrary.” The real purpose of it all, of course, is to send you off on a merry scavenger hunt through Victorian London. This is not a game that rewards thinking too much about its plot.

The more compelling aspect of Sherlock is its attention to the details of its setting. It marks the third and final Infocom game, after Trinity and The Lurking Horror, to base its geography on a real place. Bob worked hard to evoke what he calls “the wonderful Victorian era, with the gas lamps and the horse-drawn carriages and the fog,” and succeeded admirably. The newspaper included with the game is a particularly nice touch, both in its own right as one of the more impressive feelies to appear in a late-period Infocom game and as a nice little throwback/homage to the earlier tabletop classic Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective.

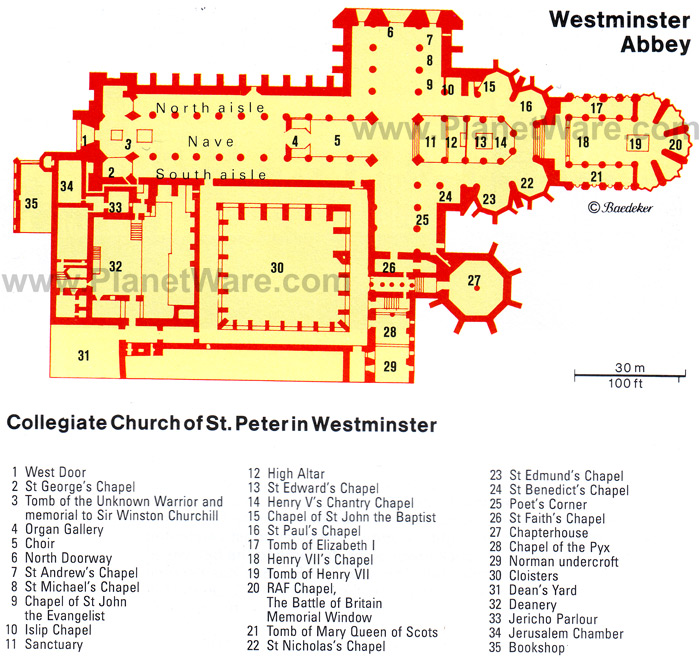

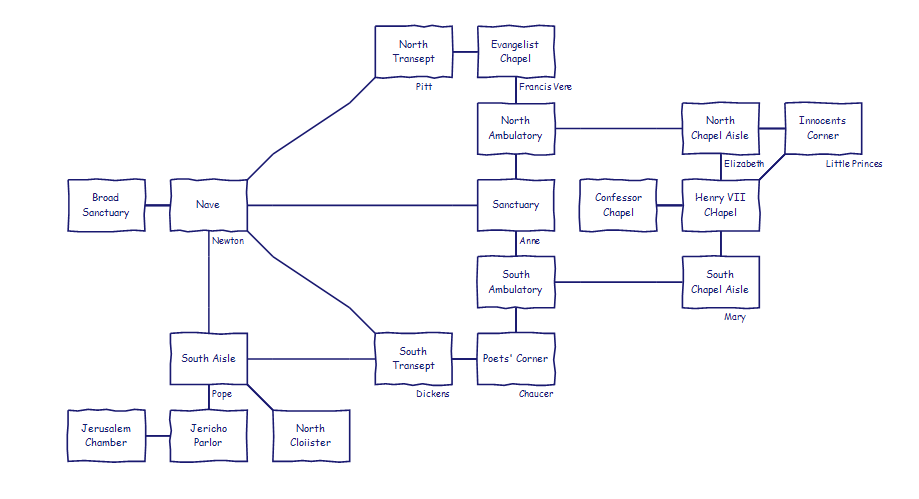

At the same time that it evokes the Victorian era, however, Sherlock gives a view of London that will be immediately recognizable to any tourist who has ever, as another Infocom game once put it, enjoyed a “$599 London Getaway Package” and “soaked up as much of that authentic English ambiance as you can.” There’s a certain “What I did on my London vacation” quality to Sherlock that’s actually a strength rather than a weakness. Appropriately for a former tour guide who was himself a semi-regular London tourist, Bob made sure to fill his version of Victorian London with the big sights his audience would recognize: Big Ben, Madame Tussaud’s, Tower Bridge, Buckingham Palace, Trafalgar Square, all right where they ought to be on the map. (The game includes a taxi service to shuttle you around among the sights.) Bob lavished particular love on Westminster Abbey, taking pains to duplicate its layout as closely as space constraints allowed from a huge, glossy book he’d purchased in the Abbey’s gift shop on one of his own visits to London.

The time limit in Sherlock — you have just 48 hours to recover the Jewels — may raise some eyebrows, but it’s quite generous as such things go, allowing you more than enough time to poke into everything and savor all of the sights. You’re much more likely to find yourself waiting around for certain things that happen at certain times than trying to optimize every move. If there is a design flaw in the game, then it must be, as Bob himself admits, the very beginning: you need to solve one of the most difficult puzzles in the game right off to get properly started. Because it isn’t initially clear where or what this puzzle is, you’re likely to spend quite some time wandering around at loose ends, unsure what the game expects from you. As soon as you cross that initial hurdle, however, Sherlock settles down into a nicely woven ribbon of clues, not too trivial but also not too horribly taxing, leading to an exciting climax that’s actually worthy of the word.

Sherlock was released in January of 1988, becoming the last of an unprecedented spurt of nine Infocom games in twelve months and, as I mentioned in introducing this article, the last all-text Infocom adventure game ever. It also marked Infocom’s last release for the Commodore 64, the third and last of the “LZIP” line of slightly larger-than-usual games (like its predecessors, Sherlock uses some of the extra space for an in-game hint system), and the end of the line for the original Z-Machine that had been conceived by Marc Blank and Joel Berez back in 1979; Infocom’s new version 6 graphical Z-Machine would retain the name and much of the design philosophy, but would for the first time be the result of a complete ground-up rewrite. Finally, Sherlock was the 31st and final Infocom adventure game to be developed on a DEC, even if the particular DEC in question this time didn’t happen to be Infocom’s own legendary “fleet of red refrigerators.”

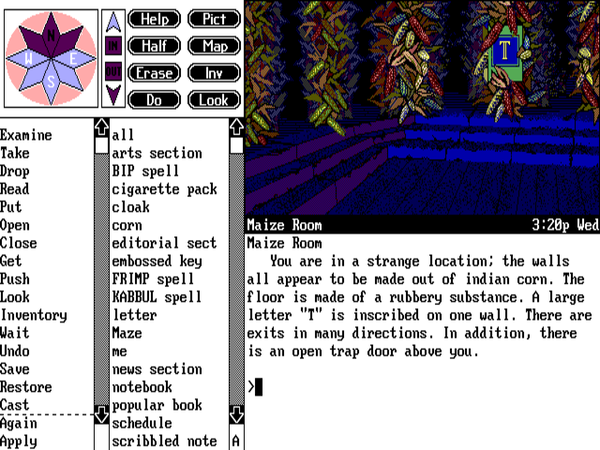

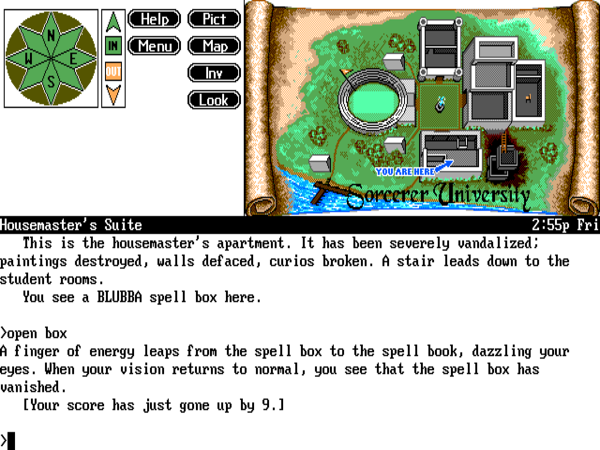

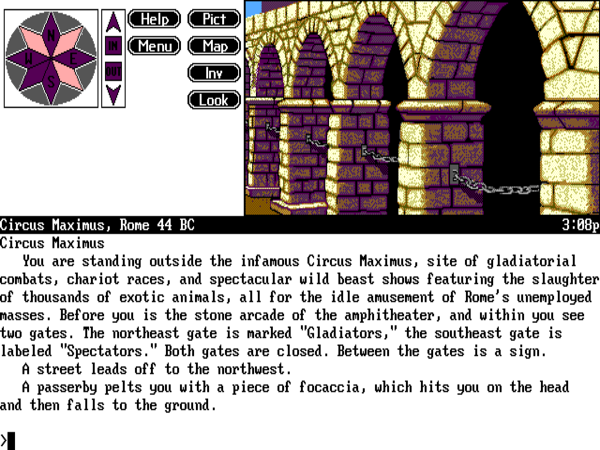

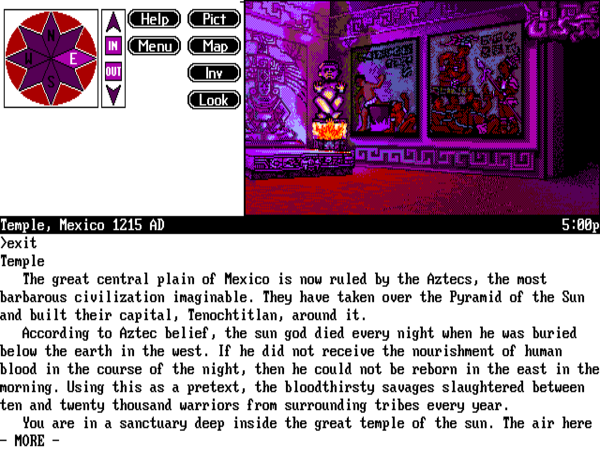

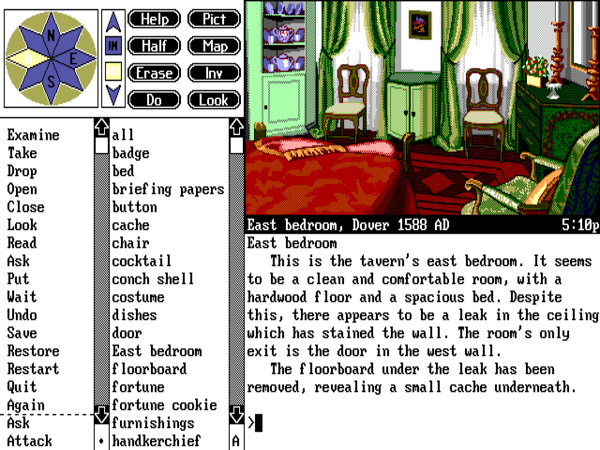

Whatever the virtues of the built-in name recognition that came with releasing a Sherlock Holmes adventure, this Sherlock Holmes adventure didn’t do notably well, as will come as no surprise to anyone who’s been following my ongoing series of Infocom articles and with it the sales travails of this late period in their history. Released at a time of chaotic transition within Infocom, just after the company had made the decision to abandon the text-only games that had heretofore been their sole claim to fame, Sherlock became yet one more member of Infocom’s 20,000 Club, managing to sell a little over 21,000 copies in all. Bob and his colleagues at Challenge were not happy. They had spent far more time and money creating the game than anticipated, what with all the heavy lifting of getting ZIL up and running in their new environment and learning to use it properly, and the financial return was hardly commensurate. In the end, though, they decided to stay the course, to make the King Arthur game they had always planned to do next using the new development system that Infocom was creating, which would at long last add the ability to include pictures in the games. Surely that would boost sales. Wouldn’t it?

The melancholia that comes attached to Sherlock, the epoch-ending final all-text adventure game from Infocom, is, as is usual for epoch-ending events, easier to feel in retrospect than it was at the time. Bob, being somewhat removed from the Infocom core, didn’t even realize at the time that there were no more all-text games in the offing. Not that it would have mattered if he had; he preferred to think about the new engine with which Infocom was tempting him. With everyone so inclined to look forward rather than behind, the passing away of the commercial text-only adventure game into history was barely remarked.

Looked at today, however, Sherlock certainly wasn’t a bad note to go out on. Being built on the sturdy foundation of everything Infocom had learned about making text adventures to date, it’s not notably, obviously innovative, but, impressively given that it is a first-timer’s game, it evinces heaps of simple good craftsmanship. We may celebrate the occasional titles like A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity that aspire to the mantle of Literature, but the vast majority of Infocom’s works are, just like this one, sturdily constructed games first and foremost. Explore an interesting place, solve some satisfying puzzles — the core appeals of a good text adventure are eternal. And, hey, this one has the added bonus that it might just make you want to visit the real London. If you do, you’ll already have a notion where things are, thanks to Bob Bates, lifelong tour guide to worlds real and virtual.

(Sources: Most of the detail in this article is drawn from an interview with Bob Bates, who was kind enough to submit to more than two hours of my nit-picky questions.)