It’s difficult to exaggerate just what a phenomenon Atari and their VCS console were in the United States of the very early 1980s. The raw figures are astounding; nothing else I’ve written about on this blog holds a candle to Atari’s mainstream cultural impact. By the beginning of 1982 the rest of the business of their parent company, the longstanding media conglomerate Warner Communications, looked almost trivial in comparison. Atari reaped six times as much profit as Warner’s entire music division; five times as much as the film division. By the middle of the year 17 percent of American households owned a videogame console, up from 9 percent at the same time of the previous year. Atari all but owned this exploding market, to the tune of an 80 percent share. The company’s very name had become synonymous for videogames, like Kleenex is for tissue. People didn’t ask whether you played videogames; they asked whether you played Atari. As the company ramped up for the big Christmas season with their home version of the huge arcade hit Pac-Man as well as a licensed adaptation of the blockbuster movie of the year, E.T., they confidently predicted sales increases of 50 percent over the previous Christmas. But then, on December 7, they shocked the business world by revising those estimates radically downward, to perhaps a 10 or 15 percent increase. Granted, plenty of businesses would still love to have growth like that, but the fact remained that Atari for the first time had underperformed. Change was in the air, and everyone could sense it.

Those who had been watching closely and thoughtfully could feel the winds of change already the previous summer, when Atari’s infamously substandard version of Pac-Man sold in massive numbers, but not quite as massive numbers as the company and their boosters had predicted; when sales on the Mattel Intellivision and the brand new ColecoVision soared, presumably at the expense of Atari’s aged VCS; when Commodore continued to aggressively market their low-cost home computers as a better alternative to a games console, and continued to be rewarded with huge sales. The big question became what form the post-VCS future of gaming would take, assuming it didn’t just fade away like the Hula Hoop fad to which videogames were so often compared. There were two broad schools of thought, who would each prove to be right and wrong in their own ways. Some thought that the so-called “second generation” consoles, like the ColecoVision, would pick up Atari’s slack and the console videogame industry would continue as strong as ever. Others, however, looked to the PC industry, which VisiCalc and the IBM PC had legitimized even as Commodore was proving that people would buy computers for the home in huge numbers if the price was right. The VIC-20 may have been only modestly more capable than the Atari VCS, but as a proof of concept of sorts it certainly got people’s attention. With prices dropping and new, much more capable machines on the horizon, many analysts cast their lot with the home computer as the real fruition of the craze that the Atari VCS had started. Full-fledged computers could offer so much better, richer experiences than the consoles thanks to their larger memories, their ability to display text, their keyboards, their disk-based storage. The newest computers had much better graphics and sound than their console counterparts to boot. And of course you could do more than play games with a computer, like write letters or help Junior learn BASIC as a leg-up for a computer world soon to come.

An increasing appreciation of the potential of home computers and computer games by the likes of Wall Street meant big changes for the pioneers I’ve been writing about on this blog. Although most of the signs of these changes would not be readily visible to consumers until the following year, 1982 was the year that Big Capital started flowing into the computer-game (as opposed to the console-centric videogame) industry. Slick new companies like Electronic Arts were founded, and old-media corporations started commissioning software divisions. The old guard of pioneers would have to adapt to the new professionalism or die, a test many — like The Software Exchange, Adventure International, California Pacific, Muse, and Edu-Ware, among dozens of others — would fail. The minority that survived — like On-Line Systems (about to be rechristened Sierra On-Line), Brøderbund, Automated Simulations (about to be rechristened Epyx), Penguin, and Infocom — did so by giving their scruffy hacker bona fides a shave and a haircut, hiring accountants and MBAs and PR firms (thus the name changes), and generally starting to behave like real companies. Thanks to John Williams, who once again was generous enough to share his memories with me, I can write about how this process worked within On-Line Systems in some detail. The story of their transformative 1982, the year that summer camp ended, begins with a venture-capital firm.

TA Associates was founded in 1968 as one of the first of the new breed of VC firms. From the beginning, they were also one of the most savvy, often seeing huge returns on their investments while building a reputation for investing in emerging technologies like recombinant DNA and gene splicing at just the right moment. They were one of the first VC firms to develop an interest in the young PC industry, thanks largely to Jacqueline Morby, a hungry associate who came to TA (and to a career in business) only at age 40 in 1978, after raising her children. While many of her peers rushed to invest in hardware manufacturers like industry darling Apple, Morby stepped back and decided that software was where the action was really going to be. It’s perhaps difficult today to fully appreciate what a brave decision that was. Software was still an uncertain, vaguely (at best) understood idea among businesspeople at the time, as opposed to the concrete world of hardware. “Because it was something you couldn’t see, you couldn’t touch, you couldn’t hold,” she later said to InfoWorld, “it was a frightening thing to many investors.” For her first big software investment, in 1980, Morby backed what would ultimately prove to be the wrong horse: she invested in Digital Research, makers of CP/M, rather than Microsoft. Her record after that, however, would be much better, as she and TA maintained a reputation throughout the 1980s as one of (if not the) major players in software VC. She described her approach in a recent interview:

If you talk to enough entrepreneurs, you quickly figure out which of their ventures are the most promising. First, I would consider the year they were formed. If a company was three years old and employed 100 people, that meant something was going right. Then, after researching what their products did, I’d call them — cold. In those days, nobody called on the presidents of companies to say, “Hi, I’m an investor and I’m interested in you. Might I come out to visit and introduce myself?” But most of the companies said, “Come on out. There’s no harm in talking.” My calling companies led to many, many investments throughout the years.

When you look at the potential of a company, the most important questions to consider are, “How big is its market and how fast is it growing?” If the market is only $100 million, it’s not worth investing. The company can’t get very big. Many engineers never ask these questions. They just like the toys that they’re inventing. So you find lots of companies that are going to grow to $5 million or so in sales, but never more, because the market for their products is not big enough.

By 1982, Morby, now a partner with TA thanks to her earlier software success, had become interested in investing in an entertainment-software company. If computer games were indeed to succeed console games once people grew tired of the limitations of the Atari VCS and its peers, the potential market was going to be absolutely huge. After kicking tires around the industry, including at Brøderbund, she settled on On-Line Systems as just the company for her — unique enough to stand out with its scenic location and California attitude but eager to embrace the latest technologies, crank out hits, and generally take things to the next level.

When someone offers you millions of dollars virtually out of the blue, you’re likely to think that this is all too good to be true. And indeed, venture capital is always a two-edged sword, as many entrepreneurs have learned to their chagrin. TA’s money would come only with a host of strings attached: TA themselves would receive a 24 percent stake in On-Line Systems; Morby and some of her colleagues would sit on the board and have a significant say in the company’s strategic direction. Most of all, everyone would have to clean up their act and start acting like professionals, starting with the man at the top. Steven Levy described Ken Williams in his natural habitat in Hackers:

Ken’s new office was just about buried in junk. One new employee later reported that on first seeing the room, he assumed that someone had neglected to take out a huge, grungy pile of trash. Then he saw Ken at work, and understood. The twenty-eight-year-old executive, wearing his usual faded blue Apple Computer T-shirt and weather-beaten jeans with a hole in the knee, would sit behind the desk and carry on a conversation with employees or people on the phone while going through papers. The T-shirt would ride over Ken’s protruding belly, which was experiencing growth almost as dramatic as his company’s sales figures. Proceeding at lightning pace, he would glance at important contracts and casually throw them in the pile. Authors and suppliers would be on the phone constantly, wondering what had happened to their contracts. Major projects were in motion at On-Line for which contracts hadn’t been signed at all. No one seemed to know which programmer was doing what; in one case two programmers in different parts of the country were working on identical game conversions. Master disks, some without backups, some of them top secret IBM disks, were piled on the floor of Ken’s house, where one of his kids might pick it up or his dog piss on it. No, Ken Williams was not a detail person.

If Ken was not detail-oriented, he did possess a more valuable and unusual trait: the ability to see his own weaknesses. He therefore acceded wholeheartedly to TA’s demands that he hire a squad of polished young managers with suits, resumes, and business degrees. He even let TA field most of the candidates. He hired as president Dick Sunderland, a fellow he had worked for before the birth of On-Line, where he had been loathed by the hackers under him as too pedantic, too predictable, too controlling, too boring. To Ken (and TA) this sounded like just the sober medicine On-Line would need to compete in the changing industry.

Which is not to say that all of this new professionalism didn’t also come with its attendant dangers. John Williams states frankly today that “some of those new managers came in with the idea that they would run the business after they pushed Ken to the side or out.” (It wasn’t clear to the Williams whether they came up with that idea on their own or TA subtly conveyed it to them during the hiring process.) Ken also clashed constantly with his own hire Sunderland; the latter would be gone again within a year. He was walking a difficult line, trying to instill the structure his company needed to grow and compete and be generally taken seriously by the business community without entirely losing his original vision of a bunch of software artisans creating together in the woods. As org charts started getting stapled to walls, file cabinets started turning up locked, and executive secretaries started appearing as gatekeepers outside the Williams’ offices, many of the old guard saw that vision as already dying. Some of them left. Needless to say, Ken no longer looked for their replacements in the local liquor store.

Ken proved amazingly adept at taking the good advice his new managers had to offer while remaining firmly in charge. After a while, most accepted that he wasn’t going anywhere and rewarded him with a grudging respect. Much of their advice involved the face that On-Line presented to the outer world. For a long time now everyone had agreed that the name “On-Line Systems,” chosen by Ken back when he had envisioned a systems software company selling a version of FORTRAN for microcomputers, was pretty awful — “generic as could be and dull as dishwater” in John Williams’s words. They decided on the new name of “Sierra On-Line.” The former part conveyed the unique (and carefully cultivated) aura of backwoods artisans that still clung to the company even in these more businesslike days, while the latter served as a bridge to the past as well as providing an appropriate high-tech flourish (in those times “On-Line” still sounded high-tech). They had a snazzy logo featuring a scenic mountain backdrop drawn up, and revised and slicked-up their packaging. The old Hi-Res Adventure line was now SierraVenture; the action games SierraVision.

Sierra hired Barbara Hendra, a prominent New York PR person, to work further on their image. Surprisingly, the erstwhile retiring housewife Roberta was a big force behind this move; her success as a game designer had revealed an unexpected competitive streak and a flair for business of her own. Hendra nagged Roberta and especially Ken — he of the faded, paunch-revealing tee-shirt and the holey jeans — about their dress and mannerisms, teaching them how to interact with the movers and shakers in business and media. She arranged a string of phone interviews and in-person visits from inside and outside the trade press, including a major segment on the prime-time news program NBC Magazine. Ken was good with these junkets, but Roberta — pretty, chic, and charming — was the real star, Sierra’s PR ace in the hole, the antithesis of the nerds so many people still associated with computer games. When someone like Roberta said that computer games were going to be the mass-market entertainment of the future, it somehow sounded more believable than it did coming from a guy like Ken.

In the midst of all this, another windfall all but fell into Sierra’s lap. Christopher Cerf, a longtime associate of The Children’s Television Workshop of Sesame Street fame, approached them with some vague ideas about expanding CTW into software. From there discussions moved in the direction of a new movie being developed by another CTW stalwart: Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets. For Ken, who had been frantically reading up on entertainment and media in order to keep up with the changes happening around his company, the idea of working with Henson was nothing short of flabbergasting, and not just because the Muppets were near the apogee of their popularity on the heels of two hit movies, a long-running television series, and a classic Christmas special with John Denver. John Williams:

Ken developed a kind of worship for two men as he began to study up on entertainment. One was Walt Disney and the second was Jim Henson. Both were men who were enablers — not known as much for their own artistry so much as their ability to bring artists and business together to make really big things happen — and that was what Ken strived for. Walt was already gone of course, but Henson was still alive.

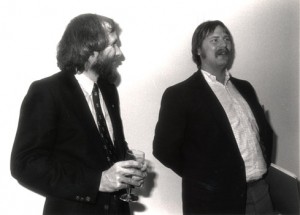

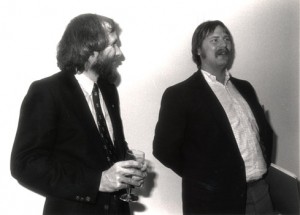

Ken Williams (right) hobnobbing with Jim Henson

The almost-completed movie was called The Dark Crystal. In the works on and off for five years, it marked a major departure for Henson and his associates. Although populated with the expected cast of puppets and costumed figures (and not a single recognizable human), there were no Muppets to be found in it. It was rather a serious — even dark — fantasy tale set in a richly organic landscape of the fantastic conceived by Henson’s creative partner on the project, designer and illustrator Brian Froud. In an early example of convergence culture, Henson and friends were eager to expand the world of the movie beyond the screen. They already planned a glossy hardcover book, a board and a card game, and a traveling art exhibit. Now an adventure game, to be designed by Roberta, sounded like a good idea. Such a major media partnership was a first for a computer-game publisher, although Atari had been doing licensed games for some time now for the VCS. Anyone looking for a sign that computer games were hitting the big time needed look no farther.

For the Williamses, the changes that the venture capitalists had brought were nothing compared to this. Suddenly they were swept into the Hollywood/Manhattan media maelstrom, moving in circles so rarified they’d barely realized they existed outside of their televisions. John Williams again:

I remember this time very well. Let me put it in a very personal perspective. I’m like 22 or 23. A guy who grew up in Wheaton, Illinois (which is just down the street from absolutely nowhere) and currently living in a town of like 5000 people 50 miles from the nearest traffic light. Now imagine this young wet-behind-the-ears punk walking through the subways and streets of Manhattan with Jim Henson, getting interviewed on WNBC talk radio while wearing his first real tailored suit. Eating at “21” with Chris Cerf, and taking limos to meet with publishing companies on Times Square. That was me – and I was just along for the ride. For Ken and Roberta, it was on a whole other level.

Much of the Williams’ vision for computerized entertainment, of games as the next great storytelling medium to compete with Hollywood, was forged during this period. If they had ever doubted their own vision for Sierra, hobnobbing with the media elite convinced them that this stuff was going to get huge. Years before the technology would become practical, they started toying with the idea of hiring voice actors and considering how Screen Actors Guild contracts would translate to computer games.

But for here and now there was still The Dark Crystal, in the form of both movie and game. Both ended up a bit underwhelming as actual works when set against what they represent to Sierra and the computer-game industry.

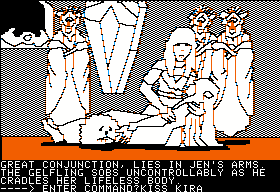

The movie is in some ways an extraordinary achievement, a living alien world built from Styrofoam, animatronics, and puppets. It’s at its most compelling when the camera simply lingers over the landscape and its strange inhabitants. Unfortunately, having created this world, Henson and company don’t seem quite sure what to do with it. The story is an unengaging quest narrative which pits an impossibly, blandly good “chosen one,” the Gelfling Jen, against the impossibly evil race of the Skeksis. It’s all rather painfully derivative of The Lord of the Rings: two small protagonists carry an object of great power into danger, with even a Gollum stand-in to dog their steps. Nor do the endless melodramatic voiceovers or the hammy voice acting do the film any favors. It’s a mystery to whom this film, too dark and disturbing for children and too hokey and simplistic for adults and with none of the wit and joy that marked Henson’s Muppets, was meant to really appeal. There have been attempts in recent years to cast the movie, a relative commercial disappointment in its time, as a misunderstood masterpiece. I’m not buying it. The Dark Crystal is no Blade Runner.

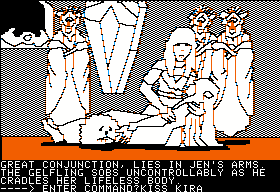

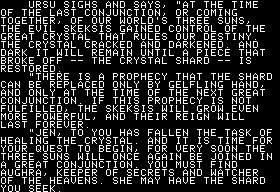

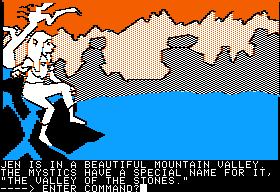

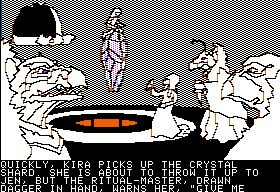

The game is similarly difficult to recommend. Like The Hobbit, The Dark Crystal‘s quest narrative maps unusually well to an adventure game, but Roberta showed none of the technical ambition that Veronika Megler displayed in making a game of her source material. The Dark Crystal suffers from the same technical and design flaws that mark all of the Hi-Res Adventure line: absurd puzzles, bad parser, barely-there world model, you’ve heard the litany before from me. In the midst of the problems, however, there are more nods toward story than we’re used to seeing in our old-school adventure games, even if they sometimes smack more of the necessities born of doing a movie adaptation than a genuine striving to advance the medium. Early on we get by far the longest chunk of expository text to make it into any of the Hi-Res Adventure line.

Unusually, the game is played in the third person, with you guiding the actions of the movie’s hero Jen and, later, both Jen and his eventual sidekick/tentative love interest, Kira. The duality of this is just odd; you never quite know who will respond to your commands. The third-person perspective extends to the graphics, which show Jen and Kira as part of each scene.

As Carl Muckenhoupt mentions in his (highly recommended) posts about the game, it’s tempting to see the graphics as a transitional step between the first-person perspective of Roberta’s earlier Hi-Res Adventure games and the fully animated adventure games that she would make next — games that would have you guiding your onscreen avatar about an animated world in real-time. It’s also very possible that working with the fleshed-out story and world of someone else inspired Roberta to push her own future original works further in the direction of real storytelling. Notably, before The Dark Crystal none of her games bothered to define their protagonists or even give them names; after it, all of them did.

Whatever influence it had on Roberta’s design approach, the fact remains that she seemed less passionate about The Dark Crystal itself than she had been about her previous games. With the licensing deal having been finalized as the movie was all but ready for release, The Dark Crystal was what John Williams euphemistically calls a “compressed timeline” game. Roberta spent only a month or so on the design while dealing with all of the distractions of her new life in the spotlight, then turned the whole thing over to Sierra’s team of in-house programmers and artists. It all feels a bit rote. John:

The simple truth is that the whole of the Dark Crystal project was, in the end, a business decision and not really driven by our developers or our creative people. I think that’s really why this is one of the least cared about and least remembered products in the Sierra stable. Look back at that game and there’s really none of Roberta’s imagination in there – and the programmers, artists, etc., involved were basically mimicking someone else’s work and creating someone else’s vision. The lack of passion shows.

The player must not so much do what seems correct for the characters in any given situation as try to recreate the events of the film. If she succeeds, she’s rewarded with… exactly what she already saw in the movie.

Adapting a linear story to an interactive medium is much more difficult than it seems. This is certainly one of the least satisfying ways to approach it. The one nod toward the dynamism that marks The Hobbit are a couple of minions sent by the Skeksis to hunt you down: an intelligent bat and a Garthim, a giant, armored, crab-like creature with fearsome pincers. If you are spotted in the open by the bat, you have a limited amount of time to get under cover — trees, a cave, or the like — before a Garthim comes to do you in. That’s kind of impressive given the aging game engine, and it does help with the mimesis that so many of the game’s other elements actively work against. But alas, it’s just not enough.

Even with the rushed development schedule, the game didn’t arrive in stores until more than a month after the movie’s December 7, 1982, premiere. After, in other words, the big Christmas buying season. That, along with the movie’s lukewarm critical reception and somewhat disappointing performance at the box office, likely contributed to The Dark Crystal not becoming the hit that Sierra had expected. Its sales were disappointing enough to sour Sierra on similar licensing deals for years to come. Ken developed a new motto: “I don’t play hits, I make them.”

Of course, it also would have been unwise to blame The Dark Crystal‘s underperformance entirely on timing or on its being tied to the fate of the movie. The old Hi-Res Adventure engine, which had been so amazing in the heyday of The Wizard and the Princess, was getting creaky with age, and had long since gone past the point of diminishing commercial returns; not only The Dark Crystal but also its immediate predecessor, the epic Time Zone, had failed to meet sales expectations. This seventh Hi-Res Adventure would therefore be the last. Clearly it was time to try something new if Sierra intended to keep their hand in adventure games. That something would prove to be as revolutionary a step as had been Mystery House. The Dark Crystal, meanwhile, sneaked away into history largely unloved and unremembered, one of the first of a long industry tradition of underwhelming, uninspired movie cash-ins. The fact that computer games had reached a stage where such cash-ins could exist is ultimately the most important thing about it.

If you’d like to try The Dark Crystal for yourself despite my criticisms, here’s the Apple II disk images and the manual.

(As always, thanks to John Williams for his invaluable memories and insights on these days of yore. In addition to the links embedded in the text, Steven Levy’s Hackers and the old Atari history Zap! were also wonderful sources. Speaking of Atari histories: I look forward to diving into Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel’s new one.)