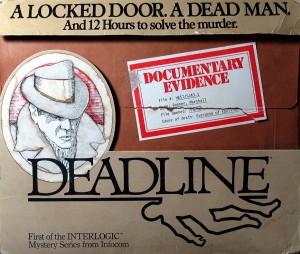

Having gotten the lay of the land and gotten a pretty good picture of the suspects, the victim, and their relationships with one another in my last post, we’ll restart today and begin investigating in earnest in the library, the scene of the crime itself. The body has of course already been hauled away, but otherwise most of what we find there is as expected from the descriptions included with the documentation. Some careful investigating, however, reveals a few vital clues that the police have overlooked.

A close look at the carpet shows a trail of mud leading from the adjoining balcony door to the position where the body was found. Going out onto the balcony, we find that one of the railings has been scuffed. Suddenly the solution to at least the locked-door part of this mystery looks pretty clear. A blank pad of paper is on the desk, along with a convenient pencil. Anyone who’s ever played an adventure game knows what to do when she sees those two things together. Sure enough, rubbing the pad with the pencil unveils fragments of the last message that Mr. Robner wrote on it:

Baxter,

st time

nsist op merg

mnidy Oth

forc

ocumen y poss

plica y Focus s

recons

late!

rsha

Mr. Robner’s desk calendar is still open to the day of his death, showing that he had a meeting that afternoon with Baxter. Turning the page to the next day, we see that he had planned to deliver his new will to Coates on the morning his body was discovered. From all this we can feel pretty confident that it was in fact a murder (as if we were in doubt…), that the murderer entered and exited via the balcony, and that George is a more likely candidate than ever — although it would be nice to know what that note to Baxter said in its entirety.

Rifling through our suspects’ bedrooms — apparently our assignment gives us authority to go and search wherever we like — turns up some seemingly innocuous items that will become important later. In George’s room we find (no surprise) some liquors; in the Robners’ room two kinds of allergy medication prescribed to Mrs. Robner; and in Dunbar’s room some blood-pressure medication along with cough medicine and aspirin.

While we are likely still in the midst of all this, at 9:07, the first of the game’s timed events fires: the phone rings. If we are smart, and near a telephone, we can be the one to answer it.

>answer telephone

You take the phone and hear a man's voice, which you don't recognize, say "Hello? Is Leslie [Mrs. Robner] there?" You start to reply, but Mrs. Robner picks up the phone from another extension and hears you speak. "I've got it, inspector," she says. "Hello? Oh, it's you. I can't talk now. I'll call you back soon. Bye!" You hear two clicks and the line goes dead.

Mrs. Robner now makes for her bedroom to return this obviously very private call. If we realize what she’s doing, we can make our own way to another extension and listen in as she returns the call.

>answer telephone

You can hear Mrs. Robner and a man whose voice you don't recognize. Robner: "...really much too early to consider it."

Voice: "But we couldn't have planned it better. You're free."

Robner: "Yes, but it will... Wait a second ... I think ..."

"Click." You realize that the call has been disconnected.

Very interesting stuff. It looks like Mrs. Robner does indeed have a paramour. “We couldn’t have planned it better” is quite ambiguous, no? Does it mean that Mr. Robner’s death was a happy accident that they couldn’t have planned better, or that their planned murder literally could not have been better, having gone off so perfectly? It seems that Mrs. Robner is guilty of being a cold-hearted bitch. But is she guilty of murder? We shall see…

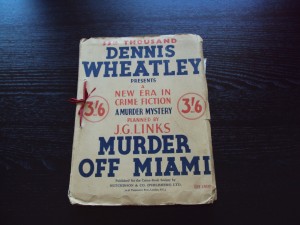

When my wife and I were playing the Dennis Wheatley dossiers together, we struggled with some things that a contemporary reader probably would not have: cues like the different appearance in photographs of a “safety razor” versus a (rather alarming sounding) “cut-throat razor”. And then there were several feelies in the last dossier in particular which we just didn’t have a clue what the hell they were. Similarly, solving Deadline requires knowing something about how a land-line phone installation functions, and knowing it is possible to listen in on others from other extensions. I suspect that in not too many more years this will be forgotten, making Deadline even more difficult than it was meant to be if it should ever receive its equivalent of the dossiers’ reprint. Maybe there are already young people running around today who lack the necessary knowledge. It’s interesting and a little disconcerting how time marches on.

But speaking of time: at 9:55 Baxter arrives and proceeds to lounge around the living room waiting for the reading of the will at noon. Then, at 10:07, the next important plot event fires: the mail arrives. It’s critical that we be on the front porch at that time to accept delivery of the one letter that comes from the mailman, because we want to see what that’s about before its recipient can get her hands on it. Said recipient is Mrs. Robner; it’s pay dirt, a letter from her lover, who is apparently named Steven. (Not, then, as I first expected, Mr. Baxter.)

>read letter

"Dear Leslie,

I am sorry to learn that Marshall has been despondent again. His obsessive interest in business must be causing you terrible anguish. It doesn't surprise me that he talks of suicide when he's in this state, but he's full of such stupid talk. I think the thought of the business going to Baxter after he's gone will keep him alive.

George has finally gone too far, eh? After all those empty threats, Marshall actually followed through. It serves the little leech right too, if you ask me. This means that should the unthinkable happen, you will be provided for as you deserve.

I'll see you Friday as usual.

Love,

Steven"

While pretty much confirming the affair, the letter if anything tends to weaken any theory of the murder as a conspiracy of the two lovers. Not only did Steven give no hint of any plan in the offing, but the fact that the new will was due to be delivered to Coates gave the lovers every reason to at least delay until that was done, and Mrs. Robner was guaranteed all rather than half of Mr. Robner’s fortune. (There certainly seems to be no love lost between her and her son.) No, this rather tends to point the finger of suspicion back toward George.

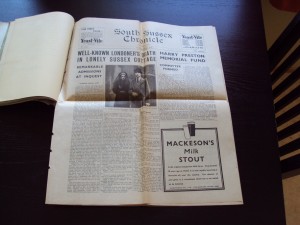

At 11:20 the newspaper comes.

>examine newspaper

The Daily Herald is a local paper in two sections. In your cursory look at the first, only a small obituary for Mr. Robner can be found. It retraces some of his career, going into some detail about the formation of Robner Corp. A few years ago, Mr. Robner and the Robner Corp. were given a prestigious award for works in the community. At that time Robner said "I am proud to accept this award for the Corporation. Robner Corp is my whole life, and I will continue to guide it for the public interest as long as I am living." Robner himself had won great public acclaim for his charitable works and community service.

>read second section

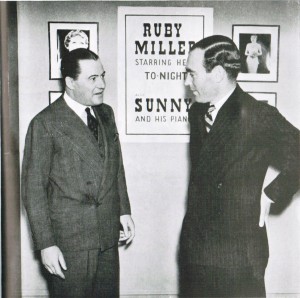

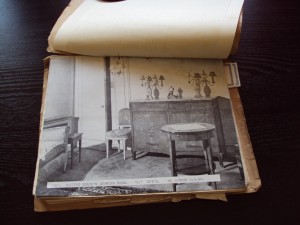

In your study of the second section, a small item in the financial section catches your eye. It seems that a merger between Robner Corp. and Omnidyne is set to be concluded shortly. There is a picture of Mr. Baxter with Omnidyne president Starkwell, both smiling broadly. Mr. Baxter is quoted as saying that the deal will enable the financially ailing Robner Corp. to continue to produce the highest-quality products. The article points out that Mr. Marshall Robner, who founded Robner Corp. but no longer is its major stockholder, had been found dead yesterday morning, an apparent suicide victim. Mr. Baxter was quoted as saying that he knew that Mr. Robner was in full agreement with the terms of the merger deal.

That phrase “as long as I am living” sounds ominous, and we’re beginning more and more to have a sense that something was not quite right between Mr. Robner and Baxter.

In the midst of making sure we are at the right place at the right time for these timed events, we should also be completing our careful examination of the house and its grounds. On the latter we find a gardening shed containing a muddy ladder (no pun intended), another innocuous object that will prove very important. We also meet a new character, the crusty old gardener Mr. McNabb, who does not live in the house or have much to do with its inhabitants and who is not considered a suspect. He is, however, vital to our investigation. A little observation will reveal that McNabb is very upset about something, and it’s not Mr. Robner’s death. A little more will reveal that someone apparently trampled all over his rose garden. We need to talk with him to learn where exactly the roses were damaged. He shows us the spot — directly below the balcony of the library. Things are becoming even clearer, especially when we compare the ladder’s feet to two holes we find in the ground there, and get a perfect match.

And now we come to the dodgiest moment in the game, the one place where it crosses from gleeful but fair cruelty (which it possesses in spades) to the sort of unfairness that was so rife in other adventure games of its era. We need to somehow divine that it’s possible to interact with the ground here, and dig three times. Doing that turns up the key clue of the game, a fragment of porcelain of the sort used in the Robners’ teacups. Sure enough, counting the cups in the kitchen reveals that, even accounting for the one still in the library, one is still missing. Everything that follows hinges on finding this fragment. Given how easy it is to miss by even the most diligent player, I suspect that this is the vital piece missed by most who attempt to solve the game, and thus the primary reason for its reputation for extreme difficulty.

So, now we have a pretty good idea how the crime was committed: the tea that Dunbar delivered to Mr. Robner must have been poisoned somehow, by her or someone else, with an overdose of his antidepressant medicine. (Significantly, George was downstairs for 10 minutes while she was making the tea.) Then someone climbed onto the balcony and into the library to replace the poisoned teacup with another, the one the lab already analyzed to find only the expected traces of tea and sugar. This same someone must have dropped the old cup while making his or her way back down the ladder, breaking it. He or she gathered the pieces as best as possible, but missed this one in the dark and stress. The puzzle, of course, is who this someone could have been. Rourke has confirmed that Mrs. Robner, George, and Dunbar must all have been snug in their beds by the time Mr. Robner died, and it’s hard to see Rourke herself climbing a ladder and vaulting a balcony railing.

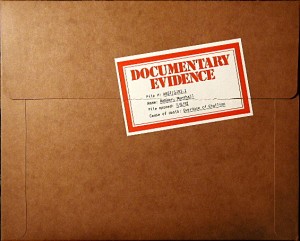

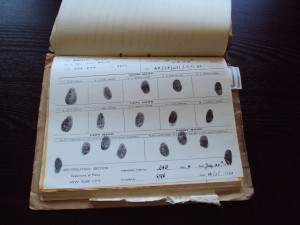

Luckily, we have another ability at our disposal that I’ve heretofore neglected to mention: we can make use of the police laboratory. When we do so, a hyper-efficient fellow named Sergeant Duffy, who would become a kind of running joke with Infocom, featuring in their later mystery games as well, sweeps onto the scene to carry the object in question off to the lab; 30 minutes or so later he sweeps back in with a report. We can check an object for fingerprints (all suspects are on file), analyze it for oddities in general, or analyze it for a specific substance. As far as I know the first possibility is a red herring; I couldn’t find any useful prints on anything. The second can turn up some useful tidbits, although nothing absolutely vital. The third, however, is vital. Remember all those innocuous ingestables we found in the suspects’ bedrooms? We need to have Duffy analyze the fragment for each of those substances to see if we can learn anything more.