David Mullich’s original plan was to write a game inspired by The Prisoner, but not a direct adaptation — an eminently sensible move considering that Edu-Ware did not own the intellectual-property rights to the show and were hardly in a position to purchase them. But Steffin and Pederson, displaying the cavalier attitude toward IP that would soon get them sued for the Space games, not only insisted that the game be called The Prisoner but even planned to use the original series’s distinctive logo. Understandably concerned, Mullich asked them to at least contact ITC Entertainment about the matter. So Steffin and Pederson called ITC and asked them whether they would mind if they — of all things — opened a Prisoner-themed restaurant. When ITC said that was okay, Steffin and Pederson reported back to Mullich that they had “permission.” They got lucky. ITC was at just that instant busy committing institutional suicide via two ill-conceived feature films: Can’t Stop the Music, a disco extravaganza starring the Village People released just in time for the big anti-disco backlash; and Raise the Titanic, an ambitious thriller which went so far over budget that it prompted ITC head Lew Grade to remark that it would have been cheaper to lower the Atlantic instead. Not only were both films commercial flops, but both also had the honor of being nominated for the first ever Golden Raspberry for Worst Picture, with Can’t Stop the Music nudging out its stablemate for the prize. Against that calamitous backdrop, the plundering of a ten-year old television series by an obscure little company in the obscure little field of computer games was not much on ITC’s radar. Yes, the media landscape was very different in 1980…

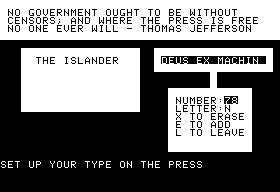

With that problem “solved,” Mullich set to work designing and coding. He created the entire game completely on his own in “about six weeks time.” That doesn’t sound like much, but remember, this is the fellow who created and coded Network from scratch in three days. The Prisoner in fact represented by far the most ambitious and complex project that Edu-Ware or Mullich had yet worked on. It consists of some 30 individual BASIC programs which are shuffled in and out of memory as needed by a machine-language routine, the only non-BASIC part of the structure.

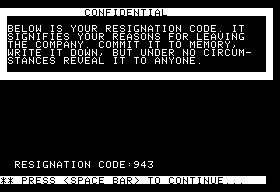

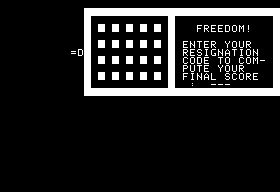

The conflict in the television series revolves around the question of why Number 6 resigned from the service — the forces that run the Village insist he tell them his reasons, and Number 6 stubbornly refuses to do so. (Of course, whether the answer to this question is really the main priority of the Village, or whether they merely want to get him to surrender this point on the assumption that once he does it will be easy to break him entirely is very much an open question.) It’s very difficult for a player to communicate such an abstract idea to a computer program even today, however, much less on a 48 K Apple II. Mullich therefore replaced the reason with a single randomly-generated three-digit “resignation code” which is presented to the player for the first and only time when she begins to play.

From here on, it will be the goal of the Island to get the player to reveal this code, whether accidentally or on purpose, while it will be the goal of the player to preserve the secret at all costs.

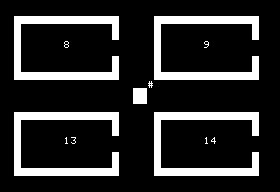

You may have noticed that I referred to the “Island” there rather than the “Village.” Perhaps in the interest of having a veneer of plausible deniability should ITC’s lawyers come calling, Mullich made a number of such changes. Rather than Number 6, for instance, the player is known as simply “#,” and the Island is run not by Number 2 but by the “Caretaker.” Even so, one never has to look hard for the source material; the player lives, as expected, in Building 6, and the Caretaker in Building 2. A bit of code diving even reveals that one of the component programs is named “Village”; apparently Mullich started with that name and never bothered to change the internal program name.

There are, however, also other influences at work here. George Orwell’s 1984 is referenced almost as prominently as The Prisoner television series. The three contradictory aphorisms of Orwell’s Oceania — “War is peace”; “Freedom is slavery”; “Ignorance is strength” — pop up over and over, singly or in tandem. The novel was also an important influence on the television show — “Questions are a burden to others; answers a prison to oneself,” reads a sign in the Village that could have come straight from Oceania — but here the debt is even more explicit. The game’s Wikipedia page currently also claims (without citation) a strong influence for Kafka’s Das Schloß (The Castle), but I’m not entirely convinced of this. While the player’s home on the Island is indeed called the Castle, there have certainly been many more surprising coincidences in literary and ludic history. I don’t really sense any other strong notes of Kafka here, and to my knowledge Mullich has never cited him as an influence. (If you know more about the validity or lack thereof of the Kafka claim, by all means chime in in the comments.)

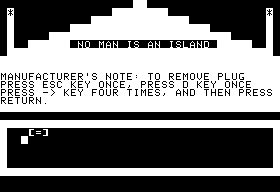

Kafka homage or not, the game proper begins with us in our Castle, which we learn to our dismay is a big maze inside. Here we are introduced to the general tricksiness of the game. We can dutifully work our way through the maze until we come to the exit. However, we can also simply hit the ESC key (get it?) to get the same result. (ESC in fact gives unexpected results in several areas of the Island, as is obliquely hinted in a few places.) Whether we take the easy or the hard way out, we cannot exit until we answer the question, “Who are you?” The correct answer is of course “#,” but here we also see the first of many attempts the game will make to trick us into entering our resignation code. This time it’s pretty transparent, but never fear, the game will soon get much trickier.

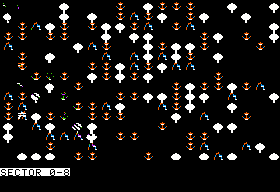

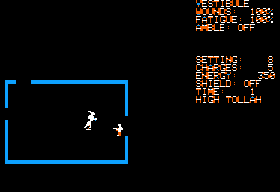

Structurally the game is built around a central spine, a map of the Island through which the player can wander.

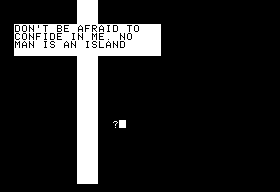

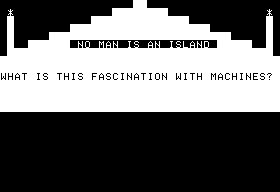

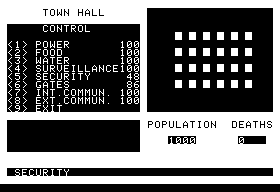

On this map are 20 individually numbered buildings, each housing a unique experience enabled by a BASIC mini-game all its own. Indeed, these games form a veritable catalog of BASIC game archetypes of the early microcomputer and late institutional computing era, the sort of concepts that in an alternative universe could have easily popped up on an HP-2000 system or the book BASIC Computer Games. In addition to the maze game in Building 6, we have a couple of ELIZA-like exercises in conversation and a game reminiscent of the early agricultural strategy game Hamurabi, albeit with the player manipulating the amount of power allotted to various Island systems rather than manipulating acres of land and bushels of crops.

In contrast to their friendly predecessors, however, this lot is an unforgiving bunch. Their messages are constantly off-putting. For example, two of the screenshots above show a famous John Donne quotation which the game twists into something sinister to join the 1984 sloganeering. If we win the Hamurabi-style game, we get a gold watch and a “place to retire,” the latter being of course the Island itself — a creepy commentary on the fate of those who are no longer considered economically useful to society. It all combines to create a constant sense of unease and paranoia. Instructions for play are often nonexistent and never complete, and the user interfaces are needlessly inconsistent. In some places, for instance, we can move an avatar using keys representing the three-dimensional compass directions of a real environment (“N,” “E,” “S,” “W”); in others, we must use the two-dimensional directions of the screen (“U,” “R,” “D,” “L”). There are hidden tricks everywhere, such that we sometimes feel it necessary to methodically tap every key on the keyboard looking for those commands the game hasn’t bothered to tell us about but which represent the only possible route to victory. And the games get tricky in other ways.

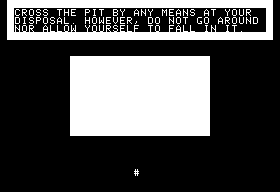

In the screenshot below, we’ve just been told to cross a pit (represented by the large white square) using “any means at our disposal.” Trouble is, all we can do is move our little avatar (represented, naturally, by the “#”) about — no jump command, no bridge-building command, nothing. What on earth to do?

Well, if we methodically move over every square that is available to us, we eventually find a piece of rope. “What do you want to do with the piece of rope?” the game asks us then. “Cross the pit,” we reply. “Sounds doubtful,” says the game. And sure enough, trying to cross still results in us falling into the pit and being returned to the Castle as punishment. So we return and try again. This time we learn that continuing to search after finding the rope yields a “bundle of sticks.” But no dice, we fall in again. Returning again, we find a third object, a “rusty old wash tub.” Into the pit we fall yet again. Finally, the fourth object, an “inflatable raft,” does the trick.

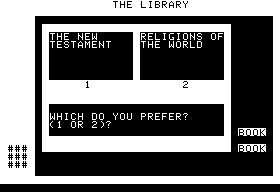

That’s frustrating, but the contents of other buildings are downright baffling. The library quizzes us on our preferences in reading material, then somehow uses that information to decide whether to award us a vital clue or burn a book in our honor. I still don’t have a clue how its algorithm actually works, and suspect that may be part of its rhetorical point.

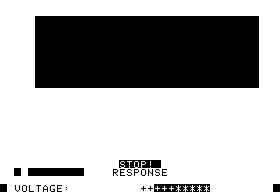

Some buildings go beyond baffling to disturbing. Building 17 houses the Island’s version of the (in)famous Milgram Experiment, in which test subjects were told by an authority figure to continue shocking another person to the point of death, and to a disturbingly large degree complied. Here we get to do the shocking, if we choose.

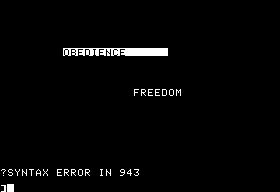

Throughout all this the game is constantly trying to get us to reveal our resignation code, through ploys obvious and subtle. The most devious of all comes when we visit the Hospital. In the midst of an absurd free-association personality test, we are suddenly dropped to BASIC with an apparent error message.

The natural reaction to the above would be to LIST line 943 to see what the problem might be. If we do, however, we have just lost. The number 943 is of course our resignation code, and we have just been tricked into revealing it. There was never any real error at all; we are still in the program. We are still the Prisoner.

Just like in the television show, the game is constantly offering us a seeming chance for escape, then pulling the rug out from under us. We can in certain situations escape from the main complex to the wilderness around it. This is the only bit of the game to use the Apple II’s hi-res graphics mode; all other displays are built using low-resolution character graphics, which suit the game perfectly. The stark black-and-white displays have almost a Constructivist feel.

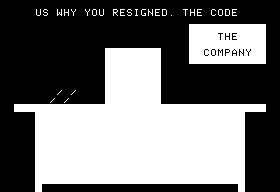

If we can dodge the Rovers, semi-sentient guardians that are lifted directly from the show, we might be able to escape via an improbably placed train station. We do. We return home. We call up the “Company” that employed us.

They ask for our resignation code, and when we refuse to give it we wind up right back where we started. This whole sequence is unusually direct about invoking television episodes like “The Chimes of Big Ben,” “Many Happy Returns,” and “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh, My Darling,” in which Number 6 seemingly returns to his home of London only to realize that his prison has followed him there as well.

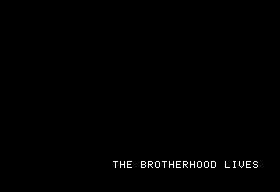

Tricks like these leave us feeling a bit like Charlie Brown out for a rousing game of football with Lucy. When we meet a seeming resistance organization called the Brotherhood, we are therefore inclined to expect more of the same.

The questions they ask us when we meet them doesn’t exactly reassure us:

“Are you willing to give your life, commit murder, commit acts of sabotage which might cause the deaths of innocent people, cheat, forge, blackmail, distribute habit-forming drugs for the cause of freedom?”

In addition to illustrating how a totalitarian society has a way of corrupting even those who believe they fight against it, they also parallel a bit too closely the questions that Orwell’s Brotherhood ask Winston and Julia in 1984:

“You are prepared to cheat, to forge, to blackmail, to corrupt the minds of children, to distribute habit-forming drugs, to encourage prostitution, to disseminate venereal diseases — to do anything which is likely to cause demoralization and weaken the power of the Party?”

That Brotherhood turned out to be an elaborate trap concocted by the Party establishment to trap would-be rebels just like Winston and Julia. By this point we’re not expecting much better.

Surprisingly, the Brotherhood turns out to be what it says it is. The fact that we are so inclined to doubt them provides a nice illustration of the effect that constant suspicion and uncertainty has on would-be resistance in a totalitarian society; even those with the bravery and inclination to fight are ineffective for lack of others they feel they can trust. (This idea was beautifully illustrated on several occasions by the television series.) If we do eventually decide to trust, we can carry out a few modest missions of sabotage and culture jamming. For one of these we must change the headlines of the local newspaper.

The screenshot above shows one of the best a-ha moments in the game, a welcome respite from the constant sense of powerlessness and oppression — we need to enter each letter using its ASCII character code.

Carrying out these missions don’t let us do anything so grand as materially overthrow the island. They do, however, score points for us, and that’s very important, because various options only become available and events only occur when our score has reached a certain number. This adds yet another layer of obfuscation to the experience, as the whole world feels in constant flux due to our changing score. Thus we must constantly revisit locations and try things again and again to see if a higher score makes a difference in what we thought we knew. We can’t even use our score to judge how far into the game we really are. While the game gives the score as “XX” of “XX,” the latter value changes along with the former with no apparent rhyme or reason in yet another nasty psychological trick.

So, how does anyone other than a masochist with the patience of a saint ever beat this thing? The answer: you cheat. Here the fact that the whole game is written in BASIC is key. We can comb through the individual programs to figure out everything that is really going on in each one and, eventually, deduce the path to victory. If we’re impatient, we can even change some of the programs to give us a higher score or otherwise make things easier. In engaging in outright psychological warfare on us the game encourages us to break the rules on our side as well. I’m certainly not the first person to make the observation that “cheating” feels right here, entirely within the spirit of the game. Number 6 never got anywhere by behaving honorably to his oppressors; he twisted and lied and manipulated, just like they did, and we love him for it. Why not here as well? There’s a little thrill that comes when we ignore the supposed rules and start to hack. I don’t know whether Mullich imagined The Prisoner this way, but God does it work brilliantly in practice.

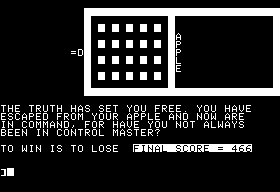

However we get there, we ultimately win by visiting the Caretaker and telling him that “the Island is just a computer game.” (We do need to have a sufficiently high score to be “ready for that realization,” contradicting Mullich’s claim in the Tea Leaves interview that it is possible to win instantly just by going to the Caretaker and telling him this.) With that realization behind us, we can unplug the computer and escape.

And after one final halfhearted bid for our resignation code, the game sets us free.

This final collapsing of the fourth wall is pretty brilliant. Just as some have argued that Number 6 was really a prisoner of himself (illustrated by the unmasking of Number 1 in the last episode), we have been voluntarily choosing to spend our time with this dystopian nightmare of a computer game. All along, we could “escape” simply by doing something else with our time. “To win is to lose,” the game tells us as its parting message, describing the feeling all gamers know of struggling with a game for days or weeks, longing for victory, only to wistfully realize… it’s all over now. Have we really won? Did Number 6 really escape?

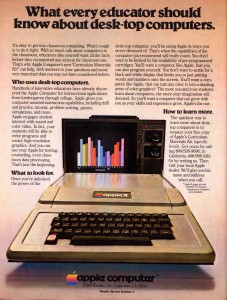

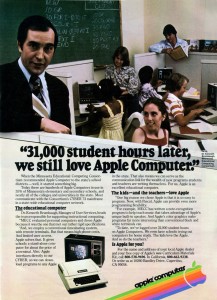

The Prisoner is teeth grindingly, soul crushingly difficult, but there is an aesthetic point to its cruelty that is absent from other early adventure games. If the design sins of Scott Adams and Roberta Williams are those of inexperienced designers working in a new medium with primitive technology, those of The Prisoner serve a real artistic purpose. It’s the first work of its kind that the nascent computer-game industry produced, a sign of what this new medium could be used for, even (dare I say it) a striving for the claim of Art. Like much conceptual art it’s uncompromising, not really something to be casually recommended as a “fun game,” but fascinating in its commitment. Its approach, of being a sort of holistic computer game that makes the interface and the code used to build it and the fact that you are having this experience on an Apple II computer part of the experience of play rather than merely paths to same, has seldom if ever been duplicated. On today’s vastly more complex systems with less technically proficient users, that would probably not even be possible.

So The Prisoner is historically important, fascinating to talk about, and just brave as hell on the part of Mullich and Edu-Ware… but, no, I’m not sure I can precisely recommend it. In addition to all the usual challenges that games of its era present to the modern player, it requires either the patience of Job or a good subset of obsolete technical knowledge — or both — to beat it. If you do want to experiment, you should be aware that the game writes data to disk as you play; most of the disk images on the Internet therefore contain games already in progress. If you’d like a clean copy to start with on your real Apple II or emulator, I have one for you here. The zip also includes a 1983 SoftSide Selections magazine with instructions for play. (The Prisoner was re-released on the SoftSide disk magazine after the release of the enhanced The Prisoner II made it no longer viable for Edu-Ware to sell on its own.)

Be seeing you!