If there was any one application that was the favorite amongst early boosters of personal computing, it was education. Indeed, it could sometimes be difficult to find one of those digital utopianists who was willing to prioritize anything else — unsurprisingly, given that so much early PC culture grew out of places like The People’s Computer Company, who made “knowledge is power” their de facto mantra and talked of teaching people about computers and using computers to teach with equal countercultural fervor. Creative Computing, the first monthly magazine dedicated to personal computing, grew out of that idealistic milieu, founded by an educational consultant who filled a big chunk of its pages with plans, schemes, and dreams for computers as tools for democratizing, improving, and just making schooling more fun. A few years later, when Apple started selling the II, they pushed it hard as the learning computer, making deals with the influential likes of the Minnesota Educational Consortium (MECC) of Oregon Trail fame that gave the machine a luster none of its competitors could touch. For much of the adult public, who may have had their first exposure to a PC when they visited a child’s classroom, the Apple II became synonymous with the PC, which was in turn almost synonymous with education in the days before IBM turned it into a business machine. We can still see the effect today: when journalists and advertisers look for an easy story of innovation to which to compare some new gadget, it’s always the Apple II they choose, not the TRS-80 or Commodore PET. And the iconic image of an Apple II in the public’s imagination remains a group of children gathered around it in a classroom.

For all that, though, most of the early educational software really wasn’t so compelling. The works of Edu-Ware, the first publisher to make education their main focus, were fairly typical. Most were created or co-created by Edu-Ware co-founder Sherwin Steffin, who brought with him a professional background of more than twenty years in education and education theory. He carefully outlined his philosophy of computerized instruction, backed as it was by all the latest research into the psychology of learning, in long-winded, somewhat pedantic essays for Softalk and Softline magazines, standard bearers of the burgeoning Apple II community. Steffin’s software may or may not have correctly applied the latest pedagogical research, but it mostly failed at making children want to learn with it. The programs were generally pretty boring exercises in drill and practice, lacking even proper titles. Fractions, Arithmetic Skills, or Compu-Read they said on their boxes, and fractions, arithmetic, or (compu-)reading was what you got, a series of dry drills to work through without a trace of wit, whimsy, or fun.

The other notable strand of early PC-based education was the incestuous practice of using the computer to teach kids about computers. The belief that being able to harness the power of the computer through BASIC would somehow become a force for social democratization and liberation is an old one, dating back to even before the first issues of Creative Computing — to the People’s Computer Club and, indeed, to the very researchers at Dartmouth University who created BASIC in the 1960s. As BASIC’s shortcomings became more and more evident, other instructional languages and courses based on them kept popping up in the early 1980s: PILOT, Logo, COMAL, etc. This craze for “computer literacy,” which all but insisted that every kid who didn’t learn to program was going to end up washing dishes or mowing lawns for a living, peaked along with the would-be home-computer revolution in about 1983. Advocating for programming as a universal life skill was like suggesting in 1908 that everyone needed to learn to take a car apart and put it back together to prepare for the new world that was about to arrive with the Model T — which, in an example of how some things never really change, was exactly what many people in 1908 were in fact suggesting. Joseph Weizenbaum of Eliza fame, always good for a sober corrective to the more ebullient dreams of his colleagues, offered a take on the real computerized future that was shockingly prescient by comparing the computer to the electric motor.

There are undoubtedly many more electric motors in the United States than there are people, and almost everybody owns a lot of electric motors without thinking about it. They are everywhere, in automobiles, food mixers, vacuum cleaners, even watches and pencil sharpeners. Yet, it doesn’t require any sort of electric-motor literacy to get on with the world, or, more importantly, to be able to use these gadgets.

Another important point about electric motors is that they’re invisible. If you question someone using a vacuum cleaner, of course they know that there is an electric motor inside. But nobody says, “Well, I think I’ll use an electric motor programmed to be a vacuum cleaner to vacuum the floor.”

The computer will also become largely invisible, as it already is to a large extent in the consumer market. I believe that the more pervasive the computer becomes, the more invisible it will become. We talk about it a lot now because it is new, but as we get used to the computer it will retreat into the background. How much hands-on computer experience will students need? The answer, of course, is not very much. The student and the practicing professional will operate special-purpose instruments that happen to have computers as components.

The pressure to make of every kid a programmer gradually faded as the 1980s wore on, leaving programming to those of us who found it genuinely fascinating. Today even the term “computer literacy,” always a strange linguistic choice anyway, feels more and more like a relic of history as this once-disruptive and scary new force has become as everyday as, well, the electric motor.

As for those other educational programs, they — at least some of them — got better by mid-decade. Programs like Number Munchers, Math Blaster, and Reader Rabbit added a bit more audiovisual sugar to their educational vegetables along with a more gamelike framework to their repetitive drills, and proved better able to hold children’s interest. For all the early rhetoric about computers and education, one could argue that the real golden age of the Apple II as an educational computer didn’t begin until about 1983 or 1984.

By that time a new category of educational software, partly a marketing construct but partly a genuinely new thing, was becoming more and more prominent: edutainment. Trip Hawkins, founder of Electronic Arts, has often claimed to have invented the portmanteau for EA’s 1984 title Seven Cities of Gold, but this is incorrect; a company called Milliken Publishing was already using the label for their programs for the Atari 8-bit line in late 1982, and it was already passing into common usage by the end of 1983. Edutainment dispensed with the old drill-and-practice model in preference to more open, playful forms of interactions that nevertheless promised, sometimes implicitly and sometimes explicitly, to teach. The skills they taught, meanwhile, were generally not the rigid, disembodied stuff of standardized tests but rather embedded organically into living virtual worlds. It’s all but impossible to name any particular game as the definitive first example of such a nebulous genre, but a good starting point might be Tom Snyder and Spinnaker Software.

Snyder had himself barely made it through high school. He came to blame his own failings as a student on his inability to relate to exactly the notions of arbitrary, contextless education that marked the early era of PC educational software: “Here, learn this set of facts. Write this paper. This is what you must know. This is what’s important.” When he became a fifth-grade teacher years later, he made it a point to ground his lessons always in the real world, to tell his students why it was useful to know the things he taught them and how it all related to the world around them. He often used self-designed games, first done with pencil and paper and cardboard and later done on computers, to let his students explore knowledge and its ramifications. In 1980 he founded a groundbreaking development company, Tom Snyder Productions, to commercialize some of those efforts. One of them became Snooper Troops, published as one of Spinnaker’s first titles in 1982; it had kids wandering around a small town trying to solve a mystery by compiling clues and using their powers of deduction. The next year’s In Search of the Most Amazing Thing, still a beloved memory of many of those who played it, combined clue-gathering with elements of economics and even diplomacy in a vast open world. Unlike so much other children’s software, Snyder’s games never talked down to their audience; children are after all just as capable of sensing when they’re being condescended to as anyone else. They differed most dramatically from the drill-and-practice software that preceded them in always making the educational elements an organic part of their worlds. One of Snyder’s favorite mantras applies to educational software as much as it does to any other creative endeavor and, indeed, to life: “Don’t be boring.” The many games of Tom Snyder Productions, most of which were not actually designed by Snyder himself, were often crude and slow, written as often as not in BASIC. But, at least at the conceptual level, they were seldom boring.

It’s of course true that a plain old game that requires a degree of thoughtfulness and a full-on work of edutainment can be very hard to disentangle from one another. Like so much else in life, the boundaries here can be nebulous at best, and often had as much to do with marketing, with the way a title was positioned by its owner, as with any intrinsic qualities of the title itself. When we go looking for those intrinsics, we can come up with only a grab bag of qualities of which any given edutainment title was likely to share a subset: being based on real history or being a simulation of some real aspect of science or technology; being relatively nonviolent; emphasizing thinking and logical problem-solving rather than fast reflexes. Like pornography, edutainment is something that many people seemed to just know when they saw it.

That said, there were plenty of titles that straddled the border between entertainment and edutainment. Spinnaker’s Telarium line of adventure games is a good example. Text-based games that were themselves based on books, published by a company that had heretofore specialized in education and edutainment… it wasn’t hard to grasp why parents might be expected to find them appealing, even if they were never explicitly marketed as anything other than games. Spinnaker’s other line of adventures, Windham Classics, blurred the lines even more by being based on acknowledged literary classics of the sort kids might be assigned to read in school rather than popular science fiction and fantasy, and by being directly pitched at adolescents of about ten to fourteen years of age. Tellingly, Tom Snyder Productions wrote one of the Windham Classics games; Dale Disharoon, previously a developer of Spinnaker educational software like Alphabet Zoo, wrote two more.

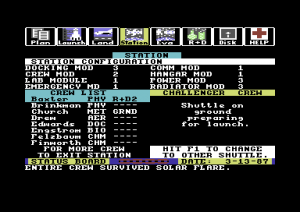

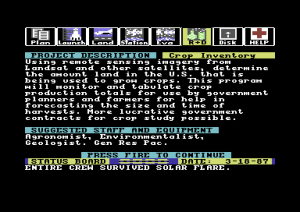

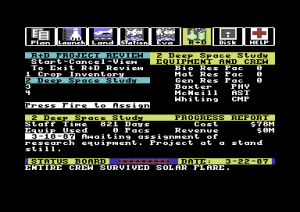

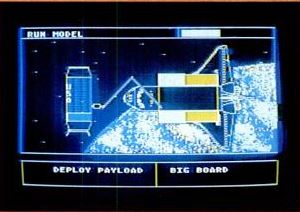

A certain amount of edutational luster clung to the text adventure in general, was implicit in much of the talk about interactive fiction as a new form of literature that was so prevalent during the brief bookware boom. One could even say it clung to the home computer itself, in the form of notions about “good screens” and “bad screens.” The family television was the bad screen, locus of those passive and mindless broadcasts that have set parents and educators fretting almost from the moment the medium was invented, and now the home of videogames, the popularity of which caused a reactionary near-hysteria in some circles; they would inure children to violence (if they thought Space Invaders was bad, imagine what they’d say about the games of today!) and almost literally rot their brains, making of them mindless slack-jawed zombies. The computer monitor, on the other hand, was the good screen, home of more thoughtful and creative forms of interaction and entertainment. What parent wouldn’t prefer to see her kid playing, say, Project: Space Station rather than Space Invaders? Home-computer makers and software publishers — at least the ones who weren’t making Space Invaders clones — caught on to this dynamic early and rode it hard.

As toy manufacturers had realized decades before, there are essentially two ways to market children’s entertainment. One way is to appeal to the children themselves, to make them want your product and nag Mom and Dad until they relent. The other is to appeal directly to Mom and Dad, to convince them that what you’re offering will be an improving experience for their child, perhaps with a few well-placed innuendoes if you can manage them about how said child will be left behind if she doesn’t have your product. With that in mind, it can be an interesting experiment to look at the box copy from software of the early home-computer era whilst asking yourself whether it’s written for the kids who were most likely to play it or the parents who were most likely to pay for it — or whether it hedges its bets by offering a little for both. Whatever else it was, emphasizing the educational qualities of your game was just good marketing; a 1984 survey found that 46 percent of computers in homes had been purchased by parents with the primary goal of improving their children’s education. It was the perfect market for the title that would come to stand alongside The Oregon Trail as one of the two classic examples of 1980s edutainment software.

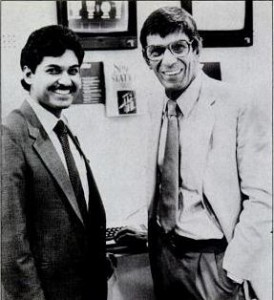

The origins of the game that would become known as Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? are confused, with lots of oft-contradictory memories and claims flying around. However, the most consistent story has it beginning with an idea by Gary Carlston of Brøderbund Software in 1983. He and his brother Doug had been fascinated by their family’s almanac as children: “We used to lie there and ask each other questions out of the almanac.” This evolved into impromptu quiz games in bed after the lights went out. Gary now proposed a game or, better yet, a series of games which would have players running down a series of clues about geography and history, answerable via a trusty almanac or other reference work to be included along with the game disk right there in the box.

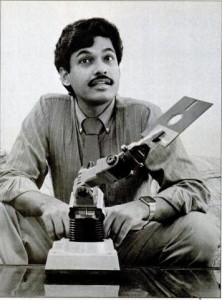

Brøderbund didn’t actually develop much software in-house, preferring to publish the work of outside developers on a contract basis. While they did have a small staff of programmers and even artists, they were there mainly to assist outside developers by helping with difficult technical problems, porting code to other machines, and polishing in-game art rather than working up projects from scratch. But this idea just seemed to have too much potential to ignore or outsource. Gary was therefore soon installed in Brøderbund’s “rubber room” — so-called because it was the place where people went to bounce ideas off one another — along with Lauren Elliott, the company’s only salaried game designer; Gene Portwood, Elliott’s best friend, manager of Brøderbund’s programming team, and a pretty good artist; Ed Bernstein, head of Brøderbund’s art department; and programmer Dane Bigham, who would be expected to write not so much a game as a cross-platform database-driven engine that could power many ports and sequels beyond the Apple II original.

Gary’s first idea was to name the game Six Crowns of Henry VIII, and to make it a scavenger hunt for the eponymous crowns through Britain. However, the team soon turned that into something wider-scoped and more appealing to the emerging American edutainment market. You would be chasing an international criminal ring through cities located all over the world, trying to recover a series of stolen cultural artifacts, like a jade goddess from Singapore, an Inca mask from Peru, or a gargoyle from Notre Dame Cathedral (wonder how the thieves managed that one). It’s not entirely clear who came up with the idea for making the leader of the ring, whose capture would become the game’s ultimate goal, a woman named Carmen Sandiego, but Elliott believes the credit most likely belongs to Portwood. Regardless, everyone immediately liked the idea. “There were enough male bad guys,” said Elliott later, and “girls [could] be just as bad.” (Later, when the character became famous, Brøderbund would take some heat from Hispanic groups who claimed that the game associated a Hispanic surname with criminality. Gary replied with a tongue-in-cheek letter explaining that “Sandiego” was actually Carmen’s married name, that her maiden name was “Sondberg” and she was actually Swedish.) When development started in earnest, the Carmen team was pared down to a core trio of Eliott, who broadly speaking put together the game’s database of clues and cities; Portwood, who drew the graphics; and Bigham, who wrote the code. But, as Eliott later said, “A lot of what we did just happened. We didn’t think much about it.”

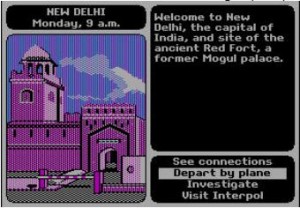

To play that first Carmen Sandiego game today can be just a bit of an underwhelming experience; there’s just not that much really to it. Each of a series of crimes and the clues that lead you to the perpetrator are randomly generated from the game’s database of 10 possible suspects, 30 cities, and 1000 or so clues. Starting in the home city of the stolen treasure in question, you have about five days to track down each suspect. Assuming you’re on the right track, you’ll get clues in each city as to the suspect’s next destination among the several possibilities represented by the airline connections from that city: perhaps he “wanted to know the price of tweed” or “wanted to sail on the Severn.” (Both of these clues would point you to Britain, more specifically to London.) If you make the right deductions each step of the way you’ll apprehend the suspect in plenty of time. You’ll know you’ve made the wrong choice if you wind up at a dead-end city with no further clues on offer. Your only choice then is to backtrack, wasting precious time in the process. The tenth and final suspect to track down is always Carmen Sandiego herself, who for all of her subsequent fame is barely characterized at all in this first installment. Capture her, and you retire to the “Detective Hall of Fame.” There’s a little bit more to it, like the way that you must also compile details of the suspect’s appearance as you travel so you can eventually fill out an arrest warrant, but not a whole lot. Any modern player with Wikipedia open in an adjacent window can easily finish all ten cases and win the game in a matter of a few hours at most. By the time you do, the game’s sharply limited arsenal of clues, cities, and stolen treasures is already starting to feel repetitive.

Which is not to say that Carmen Sandiego is entirely bereft of modern appeal. When my wife and I played it over the course of a few evenings recently, we learned a few interesting things we hadn’t known before and even discovered a new country that I at least had never realized existed: the microstate of San Marino, beloved by stamp and coin collectors and both the oldest and the smallest constitutional republic in the world. My wife is now determined that we should make a holiday there.

Still, properly appreciating Carmen Sandiego‘s contemporary appeal requires of us a little more work. The logical place to start is with that huge World Almanac and Book of Facts that made the game’s box the heaviest on the shelves. It can be a bit hard even for those of us old enough to have grown up before the World Wide Web to recover the mindset of an era before we had the world in our living rooms — or, better said in this age of mobile computing, in our pockets. Back in those days when you had to go to a library to do research, when your choices of recreation of an evening were between whatever shows the dozen or so television stations were showing and whatever books you had in the house, an almanac was magic to any kid with a healthy curiosity about the world and a little imagination, what with its thousand or more pages filled with exotic lands along with records of deeds, buildings, cities, people, animals, and geography whose very lack of context only made them more alluring. The whole world — and then some; there were star charts and the like for budding astronomers — seemed to have been stuffed within its covers.

In that spirit, one could almost call the Carmen Sandiego game disk ancillary to the almanac rather than the other way around. Who knew what delights you might stumble over while you tried to figure out, say, in which country the python made its home? The World Almanac continues to come out every year, and seems to have done surprisingly well, all things considered, surviving the forces that have killed dead typical companions on reference shelves like the encyclopedia. But of course it’s lost much of its old magic in these days of information glut. While we can still recapture a little of the old feeling by playing Carmen Sandiego with a web browser open, our search engines have just gotten too good; it’s harder to stumble across the same sorts of crazy facts and alluring diversions.

Carmen Sandiego captured so many kids because it tempted them to discover knowledge for themselves rather than attempting to drill it into them, and all whilst never talking down to them. Gary Carlston said of Brøderbund’s edutainment philosophy, “If we would’ve enjoyed it at age 12, and if we still enjoy it now, then it’s what we want. Whether it’s pedagogically correct is not relevant.” Carmen Sandiego did indeed attract criticism from earnest educational theorists armed with studies showing how it failed to live up to the latest research on learning; this low-level drumbeat of criticism continues to this day. Some of it may very well be correct and relevant; I’m hardly qualified to judge. What I do see, though, is that Carmen Sandiego offers a remarkably progressive view of knowledge and education for its time. At a time when schools were still teaching many subjects through rote memorization of facts and dates, when math courses were largely “take this set of numbers and manipulate them to become this other set of numbers” without ever explaining why, Carmen Sandiego grasped that success in the coming world of cheap and ubiquitous data would require not a head stuffed with facts but the ability to extract relevant information from the flood of information that surrounds us, to synthesize it into conclusions, and to apply it to a problem at hand. While drill-and-practice software taught kids to perform specific tasks, Carmen Sandiego, like all the best edutainment software, taught them how to think. Just as importantly, it taught them how much fun doing so could be.

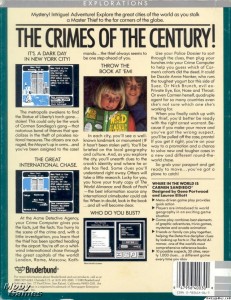

Brøderbund may not have been all that concerned about making Carmen Sandiego “pedagogically correct,” but they were hardly blind to the game’s educational value, nor to the marketing potential therein. The back cover alone of Carmen Sandiego is a classic example of edutainment marketing, emphasizing the adventure aspects for the kids while also giving parents a picture of children beaming over an almanac and telling how they will be “introduced to world geography” — and all whilst carefully avoiding the E-word; telling any kid that something is “educational” was and is all but guaranteed to turn her off it completely.

For all that, though, the game proved to be a slow burner rather than an out-of-the-gates hit upon its release in late 1985. It was hardly a flop; sales were strong enough that Brøderbund released the first of many sequels, Where in the USA is Carmen Sandiego?, the following year. Yet year by year the game just got more popular, especially when Brøderbund started to reach out more seriously to educators, releasing special editions for schools and sending lots of free swag to those who agreed to host “Carmen Days,” for which students and teachers dressed up as Carmen or her henchmen or the detectives on their trail, and could call in to the “Acme Detective Agency” at Brøderbund itself to talk with Portwood or Elliott playing the role of “the Chief.” The combination of official school approval, the game’s natural appeal to both parents and children, and lots of savvy marketing proved to be a potent symbiosis indeed. Total sales of Carmen Sandiego games passed 1 million in 1989, 2 million in 1991, by which time the series included not only Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? and Where in the USA is Carmen Sandiego? but also Where in Europe is Carmen Sandiego?, Where in Time is Carmen Sandiego?, Where in America’s Past is Carmen Sandiego?, and the strangely specific Where in North Dakota is Carmen Sandiego?, prototype for a proposed series of state-level games that never got any further; Where in Space is Carmen Sandiego? would soon go in the opposite direction, rounding out the original series of reference-work-based titles on a cosmic scale. In 1991 Carmen also became a full-fledged media star, the first to be spawned by a computer game, when Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? debuted as a children’s game show on PBS.

Through the early 1980s, Brøderbund had been a successful software publisher, but not outrageously so in comparison to their peers. At mid-decade, though, the company’s fortunes suddenly began to soar just as many of those peers were, shall we say, trending in the opposite direction. Brøderbund’s success was largely down to two breakout products which each succeeded in identifying a real, compelling use for home computers at a time when that was proving far more difficult than the boosters and venture capitalists had predicted. One was of course the Carmen Sandiego line. The other was a little something called The Print Shop, which let users design and print out signs and banners using a variety of fonts and clip art. How such a simple, straightforward application could become so beloved may seem hard to understand today, but beloved The Print Shop most definitely became. For the rest of the decade and beyond its distinctive banners, enabled by the fan-fold paper used by the dot-matrix printers of the day, could be seen everywhere that people without a budget for professional signage gathered: at church socials, at amateur sporting events, inside school hallways and classrooms. Like the first desktop-publishing programs that were appearing on the Macintosh contemporaneously, The Print Shop was one more way in which computers were beginning to democratize creative production, a process, as disruptive and fraught as it is inspiring, that’s still ongoing today.

In having struck two such chords with the public in the form of The Print Shop and Carmen Sandiego, Brøderbund was far ahead of virtually all of their competitors who failed to find even one. Brøderbund lived something of a charmed existence for years, defying most of the hard-won conventional wisdom about consumer software being a niche product at best and the real money being in business software. If the Carlstons hadn’t been so gosh-darn nice, one might be tempted to begrudge them their success. (Once when the Carlstons briefly considered a merger with Electronic Arts, whose internal culture was much more ruthless and competitive, a writer said it would be a case of the Walton family moving in with the Manson family.) One could almost say that for Brøderbund alone the promises of the home-computer revolution really did materialize, with consumers rushing to buy from them not just games but practical software as well. Tellingly — and assuming we agree to label Carmen Sandiego as an educational product rather than a game — Brøderbund’s top-selling title was never a game during any given year between 1985 and the arrival of the company’s juggernaut of an adventure game Myst in 1993, despite their publication of hits like the Jordan Mechner games Karateka and Prince of Persia. Carmen Sandiego averaged 25 to 30 percent of Brøderbund’s sales during those years, behind only The Print Shop. The two lines together accounted for well over half of yearly revenues that were pushing past $50 million by decade’s end — still puny by the standards of business software but very impressive indeed by that of consumer software.

For the larger software market, Carmen Sandiego — and, for that matter, The Print Shop — were signs that, if the home computer hadn’t quite taken off as expected, it also wasn’t going to disappear or be relegated strictly to the role of niche game machine either, a clear sign that there were or at least with a bit more technological ripening could be good reasons to own one. The same year that Brøderbund pushed into edutainment with Carmen Sandiego, MECC, who had reconstituted themselves as the for-profit (albeit still state-owned) publisher Minnesota Educational Computing Corporation in 1984, released the definitive, graphically enhanced version of that old chestnut The Oregon Trail, a title which shared with Carmen Sandiego an easygoing, progressive, experiential approach to learning. Together Oregon and Carmen became the twin icons of 1980s edutainment, still today an inescapable shared memory for virtually everyone who darkened a grade or middle school door in the United States between about 1985 and 1995.

The consequences of Carmen and Oregon and the many other programs they pulled along in their wake were particularly pronounced for the one remaining viable member of the old trinity of 1977: the Apple II. Lots of people both outside and inside Apple had been expecting the II market to finally collapse for several years already, but so far that had refused to happen. Apple, whose official corporate attitude toward the II had for some time now been vacillating between benevolent condescension and enlightened disinterest, did grant II loyalists some huge final favors now. One was the late 1986 release of the Apple IIGS, a radically updated version produced on a comparative shoestring by the company’s dwindling II engineering team with assistance from Steve Wozniak himself. The IIGS used a 16-bit Western Design Center 65C816 CPU that was capable of emulating the old 8-bit 6502 when necessary but was several times as powerful. Just as significantly, the older IIs’ antiquated graphics and sound were finally given a major overhaul that now made them amongst the best in the industry, just a tier or two below those of the current gold standard, Commodore’s new 68000-based Amiga. The IIGS turned out to be a significant if fairly brief-lived hit, outselling the Macintosh and all other II models by a considerable margin in its first year.

But arguably much more important for the Apple II’s long-term future was a series of special educational offers Apple made during 1986 and 1987. In January of the former year, they announced a rebate program wherein schools could send them old computers made by Apple or any of their competitors in return for substantial rebates on new Apple IIs. In April of that year, they announced major rebates for educators wishing to purchase Apple IIs for home use. Finally, in March of 1987, Apple created two somethings called the Apple Unified School System and the Apple Education Purchase Program, which together represented a major, institutionalized outreach and support effort designed to get even more Apple IIs into schools (and, not incidentally, more Macs into universities). The Apple II had been the school computer of choice virtually from the moment that schools started buying PCs at all, but these steps along with software like Carmen Sandiego and The Oregon Trail cemented and further extended its dominance, to an extent that many schools and families simply refused to let go. The bread-and-butter Apple II model, the IIe, remained in production until November of 1993, by which time this sturdy old machine, thoroughly obsolete already by 1985, was selling almost exclusively to educators and Apple regarded its continued presence in their product catalogs like that of the faintly embarrassing old uncle who just keeps showing up for every Thanksgiving dinner.

Even after the inevitable if long-delayed passing of the Apple II as a fixture in schools, Carmen and Oregon lived on. Both received the requisite CD-ROM upgrades, although it’s perhaps debatable in both instances how much the new multimedia flash really added to the experience. The television Carmen Sandiego game shows also continued to air in various incarnations through the end of the decade. Carmen Choose Your Own Adventure-style gamebooks, conventional young-adult novels, comic books, and a board game were also soon on offer, along with yet more computerized creations like Carmen Sandiego Word Detective. Only with the millennium did Carmen — always a bit milquetoast as a character and hardly the real source of the original games’ appeal — along with The Oregon Trail see their stars finally start to fade. Both retain a certain commercial viability today, but more as kitschy artifacts and nostalgia magnets than serious endeavors in either learning or entertainment. Educational software has finally moved on.

Perhaps not enough, though: it remains about 10 percent inspired, 10 percent acceptable in a workmanlike way, and 80 percent boredom stemming sometimes from well-meaning cluelessness and sometimes from a cynical desire to exploit parents, teachers, and children. Those looking to enter this notoriously underachieving field today could do worse than to hearken back to the simple charms of Carmen Sandiego, created as it was without guile and without reams of pedagogical research to back it up, out of the simple conviction that geography could actually be fun. All learning can be fun. You just have to do it right.

(See Engineering Play by Mizuko Ito for a fairly thorough survey of educational and edutational software from an academic perspective. Gamers at Work by Morgan Ramsay has an interview with Doug and Gary Carlston which dwells on Carmen Sandiego at some length. Matt Waddell wrote a superb history of Carmen Sandiego for a class at Stanford University in 2001. A piece on Brøderbund on the eve of the first Carmen Sandiego game’s release was published in the September 1985 issue of MicroTimes. A summary of the state of Brøderbund circa mid-1991 appeared in the July 9, 1991, New York Times. Joseph Weizenbaum’s comments appeared in the June 1984 issue of Byte. The first use of the term “edutainment” that I could locate appeared in a Milliken Publishing advertisement in the January 1983 issue of Creative Computing. Articles involving Spinnaker and Tom Snyder appeared in the June 1984 Ahoy! and the October 1984 and December 1985 Compute!’s Gazette. And if you got through all that and would like to experience the original Apple II Carmen Sandiego for yourself, feel free to download the disk images and manual — but no almanac I’m afraid — from right here.)