There are new ways of presenting information other than the traditional ways in which the reader or viewer is required to be passive. A few years ago, I realized that I didn’t know about these things, and that I’d better find out about them. The only way I could learn was to actually go and do one. So I said, “Well, I’ll just make a game and then I’ll learn.” And I certainly did.

— Michael Crichton, 1984

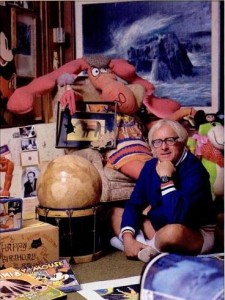

Anyone who had been reading Michael Crichton’s novels prior to the founding of the Telarium brand had to know of his interest in computers. The plot of 1972’s The Terminal Man, of a man who has a computer implanted in his brain, is the sort of thing that would become commonplace in science fiction only with the rise of cyberpunk more than a decade later. And of course computers are also all over 1980’s Congo; indeed, they’re the only reason the heroes are out there in the jungle in the first place. Crichton’s personal history with computers also stretches back surprisingly far. Always an inveterate gadget freak, he bought his first computer-like machine in the form of an Olivetti word processor almost as soon as his earnings from his first hit novel, The Andromeda Strain, made it possible. He wrote his books for years on the Olivetti. When the trinity of 1977 arrived, he quickly jumped aboard the PC revolution with an Apple II, first of a stable that within a few years would also include Commodores, Radio Shacks, and IBMs.

Never shy about sharing his interests in print, Crichton became a semi-regular contributor to Creative Computing magazine, who were thrilled to have a byline of his prominence under any terms. Thus they gave him free rein to opine in the abstract:

I would argue that it [computer technology] is a force of human evolution, opening new possibilities for our minds, simultaneously freeing us from drudgery while presenting us with a parody of our own rational sides. Computers actually show us both the benefits and the limits of rationality with wonderful precision. What could be more rational than that pedantic little box that keeps saying SYNTAX ERROR over and over? And what does our frustration suggest to us, in terms of other things to do and other ways to be?

But Crichton was more than the mere dabbler that poeticisms like the above might suggest. He took the time to learn how to program his toys, publishing fairly intricate program listings in BASIC for applications such as casting the I Ching (a byproduct of his seldom remarked interest in mysticism; see his nonfiction memoir Travels, which might just be the most interesting thing he ever wrote); identifying users based on their typing characteristics (inspired by his recent short story “Mousetrap”); and creating onscreen art mirroring that of abstract painter Josef Albers (Crichton’s interest in and patronship of the visual arts also tends to go unremarked). In 1983 he published the book Electronic Life: How to Think About Computers, a breezy introduction for the layman which nevertheless shared some real wisdom on topics such as the absurdity of the drive for “computer literacy” which insisted that every schoolchild in the country needed to know how to program in BASIC to have a prayer of success in later life. It also offered a spirited defense of computers as tools for entertainment and creativity as well as business and other practical matters.

Which isn’t to say that he didn’t find plenty of such practical applications for his computers. During this part of his life Crichton was immersed in planning for a movie called Runaway, which was to star Tom Selleck and Gene Simmons of Magnum P.I. and Kiss fame respectively. He hoped it would be one of the major blockbusters of 1984, although it would ultimately be overshadowed by a glut of other high-profile science-fiction films that year (The Terminator, Star Trek III, 2010). He hired a team to create a financial-modeling package which he claimed would allow a prospective filmmaker to input a bunch of parameters and have a shooting budget for any movie in “about a minute.” It was soon circulating amongst his peers in Hollywood.

Thus when the folks at Telarium started thinking about authors who might be interested in licensing their books and maybe even working with them on the resulting adaptations, Crichton was a natural. Seth Godin approached him in late 1983. He returned with extraordinary news: not only was Crichton interested, but he already had a largely completed game for them, based on his most recent novel, Congo.

Crichton had first started thinking he might like to write a game as long as two years before Godin’s inquiry. He’d grown frustrated with the limitations of the adventure games he’d played, limitations which seemed to spring not just from the technology but also from the lack of dramatic chops of their programmers.

I simply didn’t understand the mentality that informed them. It was not until I began programming myself that I realized it was a debugger’s mentality. They could make you sit outside a door until you said exactly the right words. Sometimes you had to say, “I quit,” and then it would let you through.

Well, that’s life in the programming world. It’s not life in any other world. It’s not an accepted dramatic convention in any other arena of entertainment. It’s something you learn to do when you’re trying to make the computer work.

Here’s what I found out early on: you can’t have extremely varied choices that don’t seem to matter. I can go north, south, east, or west, and who cares? You can only do that for a while, and then if you don’t start to have an expectation of what will happen, you’ll stop playing the game. You’d better get right going and you’d better start to have something happen.

If I play a game for a half-hour and it doesn’t make any sense to me, I’ll just quit and never go back. Say I’m locked in this house and I don’t know what the point of the house is and why I can’t get out and there’s no sort of hint to me about the mentality that would assist me in getting out — I don’t know. I could say “Shazam!” or I could burn the house down or — give me a break. I just stop.

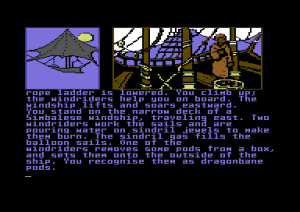

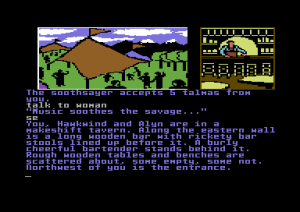

Crichton started to sketch out his own adventure game based on Congo, whose simple quest plot structure made it a relatively good choice for conversion to the new format. Realizing that his programming skills weren’t up to the task of implementing his ideas, he hired programmer Stephen Warady to write the game in Apple II assembly language. The little team was eventually completed by David Durand, an artist who normally worked in film graphics. The game as it evolved was as much a mixed-media experience as text adventure, incorporating illustrations, simple action games, and other occasional graphical interludes that almost qualify as cut scenes, perfectly befitting this most cinematic of writers (and, not incidentally, making the game a perfect match with Telarium’s other games once they finally came calling). Crichton would sometimes program these sequences himself in BASIC, then turn them over to Warady to redo in much faster assembly language. Given Crichton’s other commitments, work on Congo the game proceeded in fits and starts for some eighteen months. They were just getting to the point of thinking about a publisher when Godin arrived to relieve them of that stress.

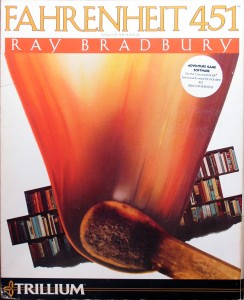

When Spinnaker started their due diligence on the deal, however, a huge problem quickly presented itself: Crichton, as was typical for him by this time, had already sold the media rights to Congo to Hollywood. (After they languished there for many years, the success of the Jurassic Park film would finally prompt Paramount Pictures to pick them up and make a Congo movie at last in 1995. Opinions are divided over whether that movie was just bad or so cosmically bad that it became good again.) Those rights unfortunately included all adaptations, including computer games, something the usually business-savvy Crichton had totally failed to realize. Spinnaker may have been a big wheel in home computers, but they didn’t have much clout in Hollywood. So, they came up with another solution: they excised the specifics of the novel from the game, leaving just the plot framework. The Congo became the Amazon; Amy the signing gorilla became Paco the talking parrot; Earth Resources Technology Services became National Satellite Resources Technology; a diamond mine became an emerald mine; African cannibals and roving, massacring army troops became South American cannibals and roving, massacring army troops. It may not have said much for Crichton and Spinnaker’s appreciation for cultural diversity, but it solved their legal problems.

Amazon was written for the Apple II in native assembly language. Spinnaker, however, took advantage of the rare luxury of time — the game was in an almost completed state when Crichton signed in late 1983, fully one year before the Telarium line’s launch — to turn it over to Byron Preiss Video Productions to make a version in SAL for the all-important Commodore 64 platform. The result wasn’t quite as nice an experience as the original, but it was acceptable. And it was certainly a wise move: Amazon became by all indications the most successful of all the Telarium games. Some reports have it selling as many as 100,000 copies, very good numbers for a member of a line whose overall commercial performance was quite disappointing. The majority of those were most likely the Commodore 64 version, if sales patterns for Amazon matched those for the industry as a whole.

I do want to talk about Amazon in more detail; it’s an historically important game thanks if nothing else to Crichton’s involvement and also a very interesting one, with some genuinely new approaches. But we’ll save that discussion for next time. In the meantime, feel free to download the Apple II version from here if you’d like to get a head start. Note that disk 3 is the boot disk.

(All of the references I listed in my first article on bookware still apply. Useful interviews with Crichton appeared in the February 1985 Creative Computing and February 1985 Compute!. Other articles and programs by Crichton appeared in Creative Computing‘s March 1983, June 1984, and November 1984 issues.)